22 May 2023: Clinical Research

A Study of 179 Patients with Degenerative Stenosis of the Lumbosacral Spine to Evaluate Differences in Quality of Life and Disability Outcomes at 12 Months, Between Conservative Treatment and Surgical Decompression

Dawid SobańskiDOI: 10.12659/MSM.940213

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940213

Abstract

BACKGROUND: This prospective study included 179 patients with degenerative stenosis of the lumbosacral spine and aimed to evaluate the outcomes of conservative treatment and surgical decompression on quality of life and disability over 12 months.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The surgery group consisted of 96 patients with degenerative stenosis of the lumbosacral spine who qualified for surgical decompression, while the conservative-treatment group included 83 patients who qualified for conservative treatment. We used the Satisfaction with Life Scale questionnaire, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) questionnaire, the Visual Analog Scale to assess the severity of pain, the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire to assess the degree of disability, and the Sexual Satisfaction Scale at 0, 1, 6, and 12 months after treatment.

RESULTS: Statistical analysis showed a positive relationship between conservative and surgical treatment and quality of life (P<0.05). A significant reduction in the severity of pain (P<0.05) and the degree of disability (P<0.05) were both recorded during the 12-month followup period in both groups. Women of both groups declared significantly lower satisfaction than men at every time point (P<0.05).

CONCLUSIONS: Most patients in both groups declared an improvement in their quality of life, with the surgery group showing a higher percentage of responses that their quality of life had improved. Based on the results obtained from the FACIT-F questionnaire, degenerative stenosis of the lumbosacral spine had a non-root effect on the patients’ lives in the surgery group.

Keywords: Life Style, Low Back Pain, Lumbar Stenosis, Familial, Orgasm, Sexual Dysfunctions, Psychological, Male, Humans, Female, Constriction, Pathologic, Prospective Studies, Quality of Life, conservative treatment, Spinal Stenosis, Decompression, Surgical, Lumbar Vertebrae, Treatment Outcome

Background

Stenosis of the lumbosacral (L/S) spine (LSS) is a reduction in the space of the spinal canal, causing compression of nerve and vascular elements within the lumbar spine. This condition occurs most often in the fifth and sixth decade of life [1]. Clinical symptoms are characterized by pain in the buttocks and lower extremities; in some cases, there may also be lower back pain [1–3]. Intermittent claudication, a characteristic of lumbar stenosis, occurs during an upright position and walking [1–3]. However, it disappears in sitting, lying down, and during forward bending [1–3]. There are 2 types of lumbar stenosis [3]. The first is congenital stenosis and the second type is acquired degenerative stenosis, in which the vertebral canal in the sagittal dimension is less than 10–12 mm but was originally of standard size [4]. It arises as a result of hypertrophic changes in the bony and articular elements of the spinal canal and occurs most often in people in their fifties and sixties [3–5]. Lumbar stenosis most commonly affects the L4/L5 level, followed by L3/L4, and L2/L3 [6]. Less commonly, the L5/S1 and L1/L2 spaces are involved [6].

Treatment of degenerative stenosis can aim to alleviate symptoms (conservative treatment – pharmacological and rehabilitative) or can target the root cause (neurosurgical procedure to widen the lumen of the spinal canal) [7,8]. The treatment of LSS should first be carried out using conservative methods. Only when conservative treatments are unsuccessful or the neurological symptoms are very advanced should the choice be made to consider surgical treatment involving decompression of the spinal canal. The goal of decompression treatment should be to widen the lumen of the spinal canal as much as possible while maintaining spinal stability. The success rate of operative treatment is about 85% and generally results in a greater measurable reduction of negative symptoms [7,9].

Chronic, aggravated L/S spine pain is closely related to the deterioration of motor function, deterioration of general health, withdrawal of the patient from social and recreational life, family stress or loss of ties with the group and community, disorders of psychological functioning (insomnia, irritability, anxiety, depression, and somatic complaints), and neuro-urological disorders [10].

Quality of life is defined by the World Health Organization as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value system in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations and standards” [11]. The study of quality of life is an interdisciplinary issue that combines clinical relevance with the psychological aspects of medical care [12]. In 1989, Patrick and Deyo developed questionnaires to assess patients’ quality of life [13]. This was to help distinguish the quality of life in disease states from a more general concept of quality of life that is difficult to define and that depends on many factors; for example, cultural, environmental, professional, material, social status, and health factors [13].

In terms of the nomenclature, the Patrick and Deyo questionnaires are divided into general and specific questionnaires [14]. The first type of questionnaire is used to assess the relationship between the patient’s health status and numerous factors, such as family relations, emotional state, and occupational activity [14]. Specific questionnaires, by contrast, are generally divided into 2 categories [14]. The first provides an analysis of specific spheres of the patient’s functioning (domain-specific) [14]. The second category analyzes factors arising from the disease itself (disease-specific) [14]. This is important because of the possibility of assessing the patient’s well-being, the severity of symptoms, and the impact of the disease on their emotional state and daily social and professional activities [14].

The most commonly used questionnaires for assessing quality of life include the medical outcomes study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), the Sickness Impact Profile, the World Health Organization Quality of Life, and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) [15]. The SWLS measures feelings of satisfaction with life [16]. Pain intensity is usually assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which is commonly used in pain assessment studies [17]. The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, measured as Oswestry disability index (ODI), assesses the degree of disability caused by low back pain [18]. The 13-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) questionnaire assesses the level of fatigue while performing daily tasks the week before patients completed the questionnaire [19].

Parker et al evaluated cost, pain, disability, and quality of life in patients with lumbar spondylolisthesis (n=50), stenosis (n=50), and disc herniation (n=50) [20]. They noted that in nearly a third of patients, 6-week conservative treatment did not yield the expected results, and patients were qualified for surgery [20]. Significant improvements were found only in pain and disability [20]. Özdemir et al assessed the quality of life and grade of disability among patients with degenerative spinal stenosis compared with a control group [21]. The authors unanimously concluded that quality of life was significantly reduced in the study group [21]. The main influencing factors were the severity of the disability, emotional state, and the degree of loss of free movement (“lameness”) [21]. Bello et al showed significant improvements in quality of life, reduced disability, and pain relief in 52 patients operated on for degenerative spinal stenosis [22]. Ulrich et al evaluated the frequency of reoperation in patients with degenerative spinal stenosis and its impact on patients’ quality of life and disability. The authors indicated that after necessary revision surgery, the severity of pain and disability increased significantly [23].

Based on the available literature, it seems that the quality of life, disability, and surgical outcomes in patients with lumbar degenerative stenosis in the Polish population have not been assessed sufficiently to be well understood [21–23]. Admittedly, Lubkowska et al analyzed quality of life in patients with low back pain in the Polish population, but they did not focus on patients with degenerative stenosis and did not assess changes in quality of life over time [24]. Therefore, this prospective study included 179 patients with degenerative stenosis of the L/S spine, and aimed to assess the differences in quality of life and disability outcomes at 12 months between conservative treatment and surgical decompression.

Material and Methods

ETHICS:

This study was performed following the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki guidelines on human experimentation. Approval for the study was obtained from the Bioethical Committee operating at the Regional Medical Chamber in Cracow, no 162/KBL/OIL/2021. Data confidentiality and patient anonymity were maintained at all times. Patient-identifying information was deleted before the database was analyzed. Identifying patients on an individual level has been rendered impossible, either from this article or from the database.

STUDY DESIGN:

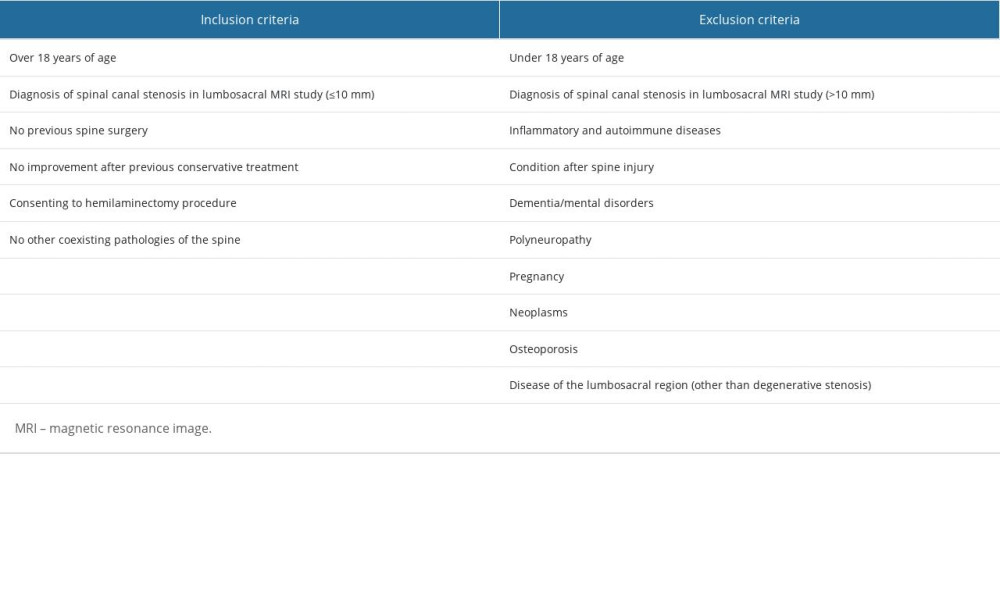

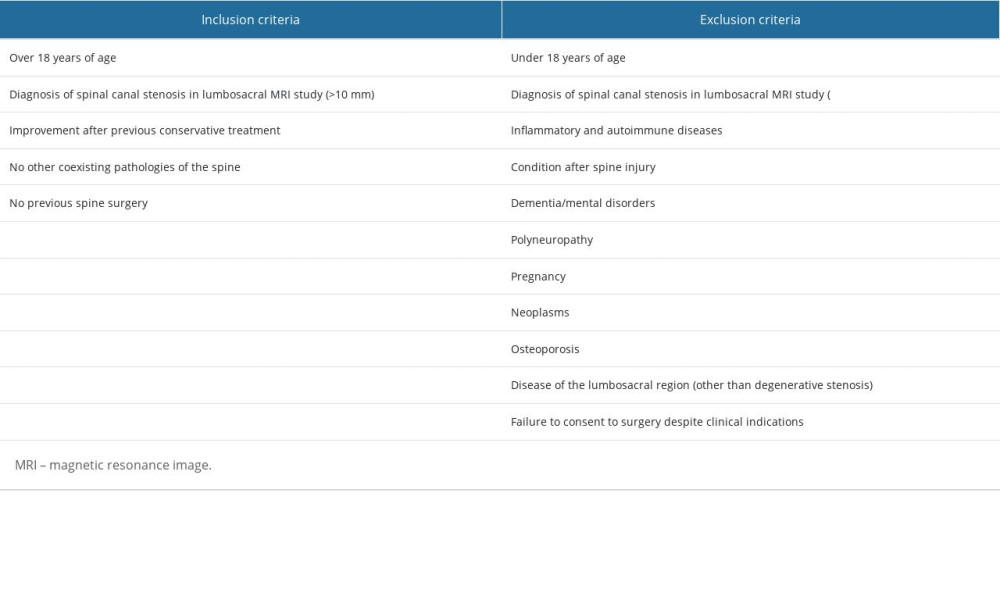

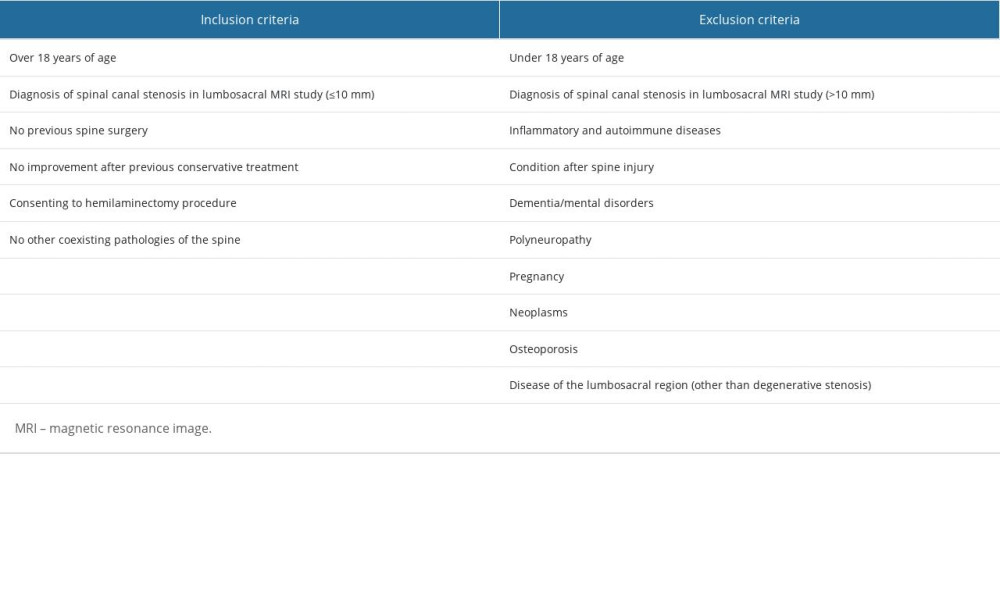

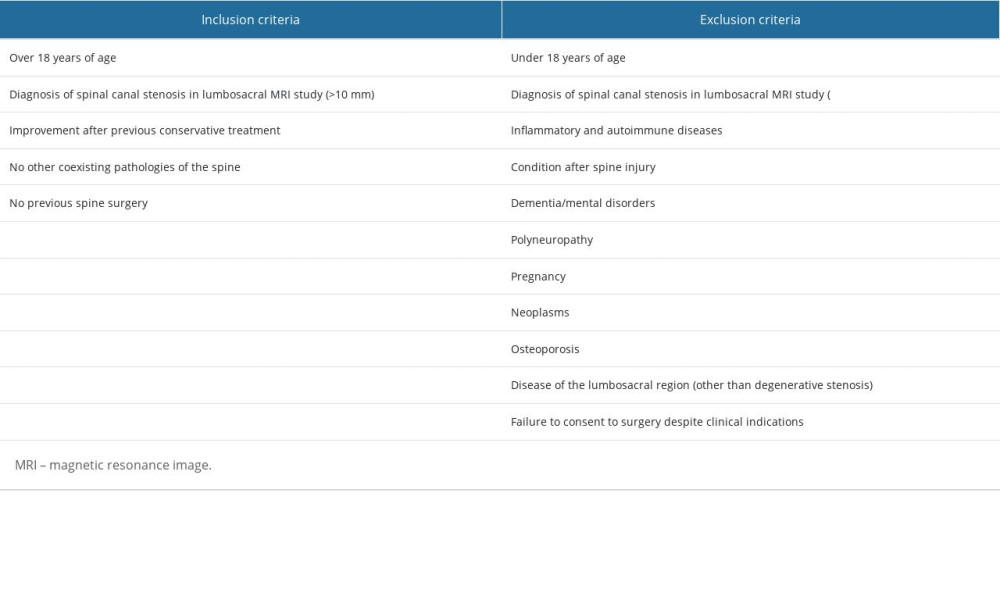

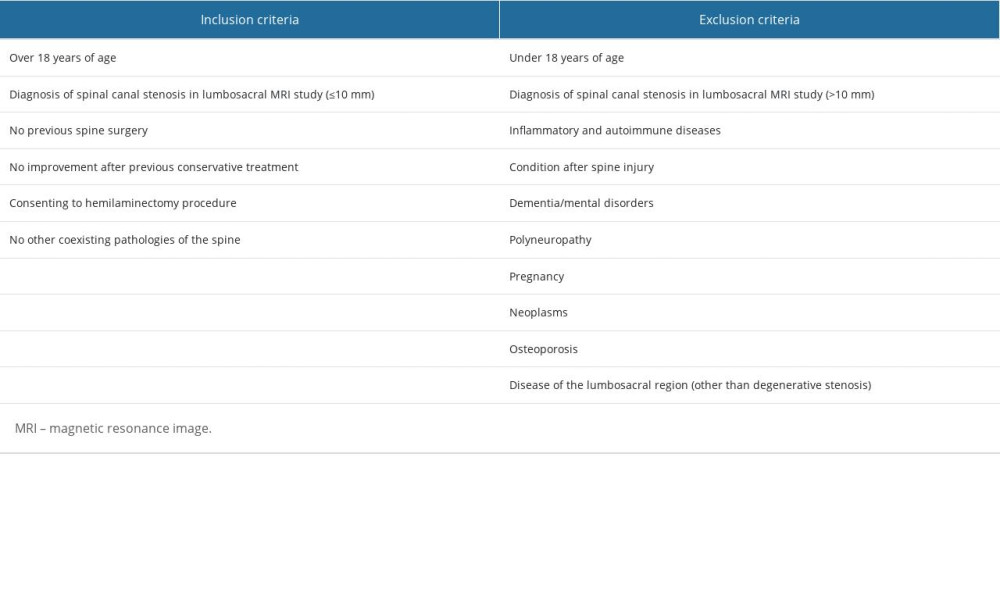

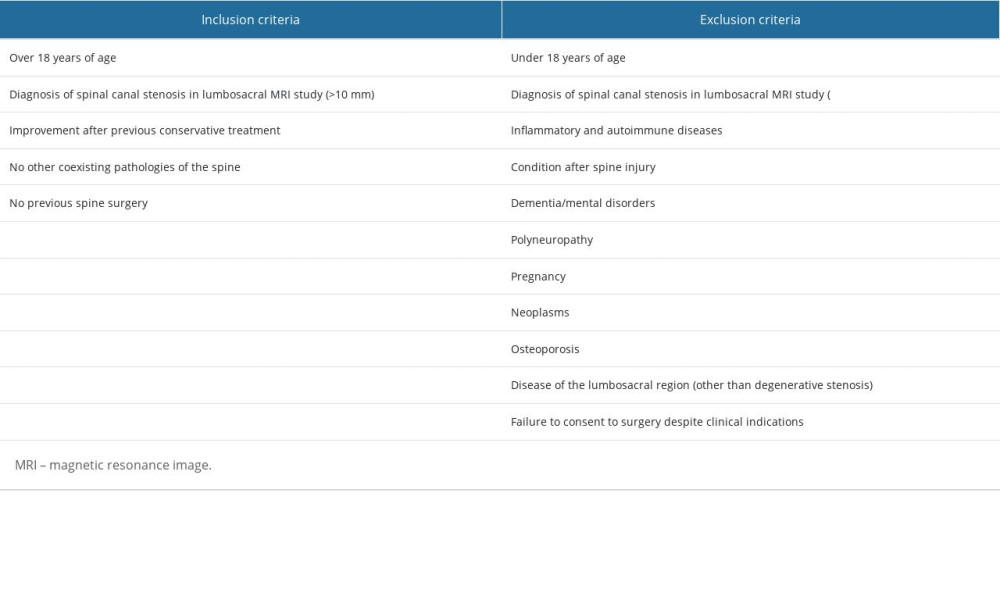

This study included 2 groups: the patients treated surgically and those treated with conservative treatment. The group of patients treated surgically consisted of 96 patients, aged 68.3±2.4 years (50 male, 46 female), with diagnosed degenerative LSS, who had been previously treated conservatively (pharmacotherapy and rehabilitation) for 5.9±0.7 years, without the expected level of improvement. These patients qualified for spinal canal decompression and the release of nerve structures by performing hemilaminectomy according to standard procedures. None of the patients had a history of spinal surgery. In the conservative-treatment group, stenosis at the L1/L2 level was found in 5 patients, L2/L3 in 6 cases, L3/L4 in 56 cases, L4/L5 in 90 cases, and L5/S1 in 4 cases. Stenosis often involves multiple levels in a single patient [6]. The side on which decompression was performed was selected based on the lateralization of clinical symptoms. If the clinical symptoms were not lateralized, the side with the greatest tightness on imaging was selected. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the group of patients treated surgically are presented in Table 1. However, the group of patients treated conservatively included 83 patients aged 62.4±1.8 years (40 men, 43 women) diagnosed with degenerative stenosis of the L/S spine, for whom pharmacotherapy and rehabilitation were sufficient treatments. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) examination showed a narrowing of the spinal canal lumen in the range of 11–15 mm. Patients complained of pain in the L/S spine, without features of chronic discontinuity, and neurological deficits, including muscle weakness in the lower extremities. In the conservative-treatment group, stenosis at the L1/L2 level was found in 9 patients, L2/L3 in 13 cases, L3/L4 in 23 cases, L4/L5 in 21 cases, and L5/S1 in 1 case. The mean duration of treatment in the group of patients treated conservatively was 7.1±3.5 years. This group did not include cases for which surgical spinal canal decompression was indicated, and the patients did not consent to the proposed invasive treatment. Patients in both groups were evaluated for the level of the most significant stenosis and the distance of intermittent claudication. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the group of patients treated conservatively are presented in Table 2. In each case, 2 neurosurgeons independently assessed the MRI results and examined each patient before making a decision about the continuation of conservative treatment or the need to implement surgical treatment for stenosis.

HEMILAMINECTOMY PROCEDURE:

The method used was the removal of the vertebral arch on 1 side (hemilaminectomy), adjacent yellow ligaments, and hypertrophied intervertebral joint elements. The main surgeon was Dawid Sobański. Using this type of decompression, the nerve elements – that is, the meningeal sac and the roots inside the sac and exiting through the root canals – are released. The stability of the spine remains unaffected. This surgery allows for optimal decompression without destabilizing the lumbar spine.

In the group treated surgically, surgery was performed under general anesthesia. During the process, the patient was positioned on the abdomen. Using a C-arm, an X-ray (Ziehm, Nuremberg, Germany) was taken to verify the surgical level. The skin was then incised longitudinally over the designated level of the lumbar spine in the medial line. Using scissors, the paravertebral muscles on the side of the target decompression were peeled away. The C-arm was used again to confirm the surgical level. Using a No. 11 knife, the hypertrophied yellow ligament hidden between the hypertrophied bony elements of the spine was incised. Decompression was performed using Kerrison punch and Luer bone rongeur forceps, removing part of the vertebral arch, leaving the other part of the arch, the spinous process and long spinal ligament complex, the adjacent yellow ligament, and the hypertrophied spinal joint elements. At this point, the procedure was completed by placing a Redon drain and restoring tissue continuity in the layers. The entire process was carried out using an operating microscope.

Surgical treatment involving the decompression of nerve elements was conducted to enlarge the anteroposterior diameter but mainly to increase the cross-sectional area of the spinal canal. The removed spinal features enclosing the meningeal sac allow the nerve structures to move freely. No early or late postoperative complications were reported.

POSTOPERATIVE PERIOD:

On the first day after hemilaminectomy, the patients were placed in the upright position, and early rehabilitation was instituted in the neurosurgical unit. The average length of a patient’s stay from admission to the ward to discharge was 5 days. Patients were instructed on the principles of wound care and the daily need to disinfect the wound and change a sterile dressing with an area no smaller than the length of the surgical wound. Postoperative followup took place about 4 weeks after surgery.

Further improvement was carried out via followup treatment by qualified physiotherapists and rehabilitation specialists in accordance with accepted standards, and included 15 treatment days. Rehabilitation treatment included kinesitherapy, including general mobility exercises, isometric exercises, fascial stretching, and physiotherapy, including light therapy, laser therapy, and low-frequency magnetic fields. All patients had the same access to rehabilitation treatment. In addition, each of them was provided with the same rehabilitation treatments, performed by the same team of physiotherapists.

ASSESSMENT OF SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY TREATED PATIENTS BY SATISFACTION WITH LIFE SCALE:

The SWLS tool consists of 5 statements that respondents rate on a 7-point scale. The respondents assess the extent to which each statement relates to his or her life to date [16]. The respondents are asked to answer 5 questions, measured on a 7-point scale. A value of 1 means “strongly disagree” with a statement, 2 means “disagree,” 3 means “slightly disagree,” 4 means “neither agree nor disagree,” 5 means “slightly agree,” 6 means agree, and 7 means “strongly agree.” After assigning a score of 1–7 to each account and adding up the scores, overall satisfaction and satisfaction with life were determined. The questions in the questionnaire are open to interpretation and, therefore, appropriate for adults with different backgrounds. The score obtained represents the overall degree of satisfaction with life. Scores ranged from 5 to 35 points. The higher the score, the higher the sense of satisfaction with life. In interpreting the scores, they were first converted to “standardized 10” or “sten” scores. On the sten scale, values between 1 and 4 sten are considered low scores, scores between 5 and 6 sten are considered average, and scores between 7 and 10 sten are considered high.

The patients were asked to respond to the following statements

In our work, analyzing the results obtained from the SWLS questionnaire, we assumed 3 possible situations:

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN LEVELS IN THE PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY:

The VAS takes the form of a 10-cm ruler with appropriate markings. The beginning of the line means no pain, the middle means moderate pain, and the end refers to unimaginable pain. The scale is 10 points, with 0 indicating no pain at all, and 10 indicating unbearable pain (the worst pain a patient can imagine). The assessment was made after verbally explaining the idea and interpretation of the VAS to the patient. Patients were also given unlimited opportunity to ask the doctor additional questions and request clarifications.

EVALUATION OF THE OSWESTRY LOW BACK PAIN DISABILITY QUESTIONNAIRE IN THE PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY:

On the ODI questionnaire, the respondents answered 10 questions regarding (1) pain intensity; (2) self-care (washing, dressing independently, etc.); (3) lifting objects; (4) walking; (5) sitting; (6) standing; (7) sleeping; (8) sex life (if applicable); (9) social life; and (10) traveling. A score of 0 to 5 points can be obtained for each question. The score is presented on a point scale (0–50 points, where 0 indicates no dysfunction and 50 indicates the worst condition of the patient) or on a percentage scale. Using a 5-point scale, an evaluation of the degree of disability can be done as shown below [26,26]:

ASSESSMENT OF CHRONIC ILLNESS AND THERAPY-FATIGUE IN THE PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY:

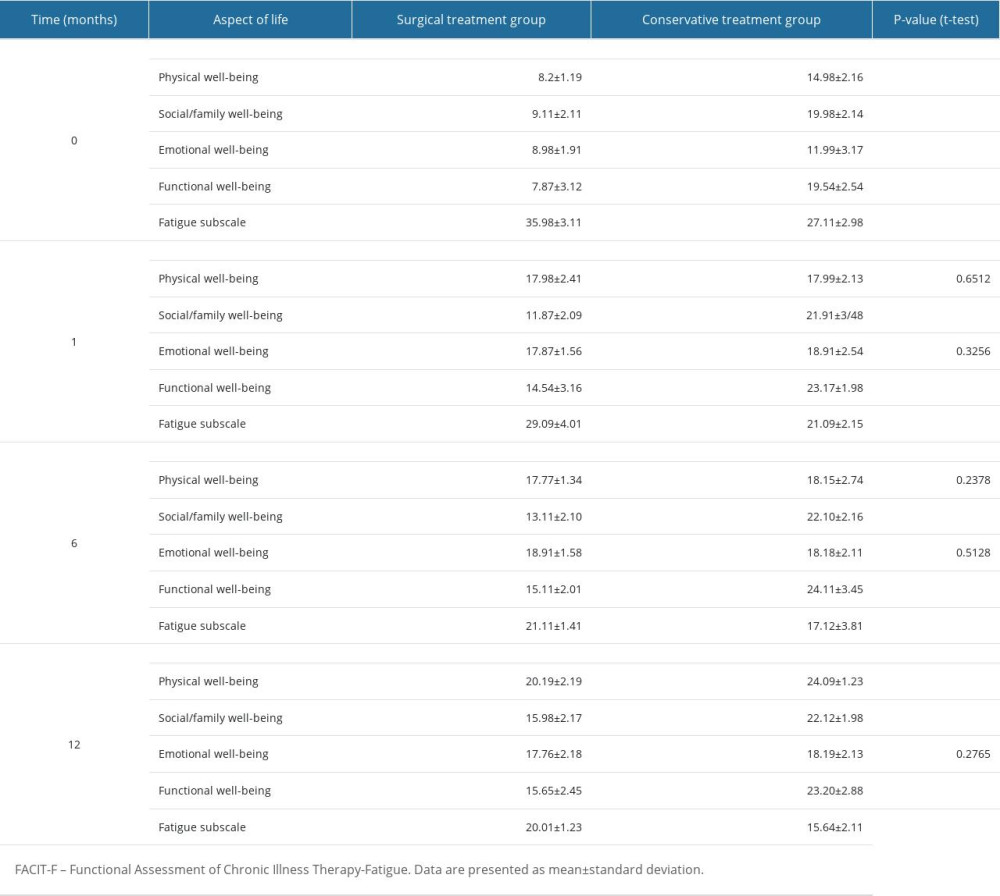

On the FACIT-F questionnaire, respondents rate each statement on a 5-point scale, where 0 means “very tired” and 4 means “not at all tired”. The scale assesses the impact of the disease on 4 aspects of life: (1) physical well-being (7 questions) has a maximum of 28 points, where a value >14 points indicates a good, satisfactory score; (2) social/family well-being (7 questions) has a maximum of 28 points, where >15 points should be defined as a good, satisfactory score; (3) emotional well-being (6 questions) has a maximum of 24 points, where >13 points is a good/satisfactory score; (4) functional well-being (7 questions) has a maximum of 28 points, where a score >14 points is interpreted as a good/satisfactory score; (5) fatigue subscale (13 questions) has a maximum of 52 points, with fatigue status indicated by >26 points. The FACIT-F determines the subjects’ overall quality of life in individual aspects, with >80 points considered acceptable.

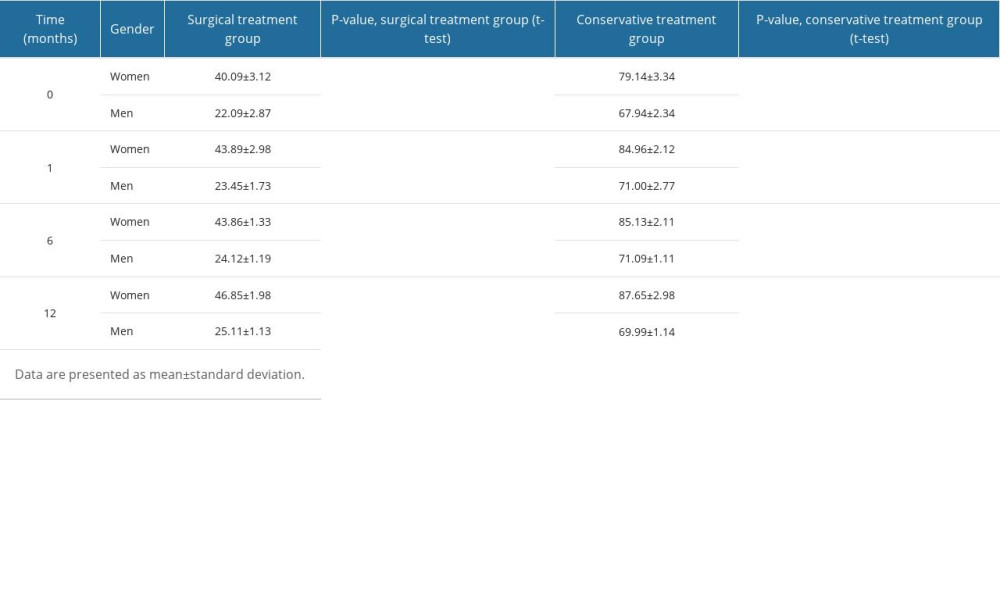

ANALYSIS OF THE SEXUAL SATISFACTION SCALE IN THE PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY:

The level of self-reported sexual satisfaction was measured using the Davies Sexual Satisfaction Scale (SSS), translated into Polish by Szumski and Malecki [27]. The questionnaire consisted of 21 statements, which respondents answered using a 5-point Likert scale (1-Strongly Disagree, 2-Disagree, 3-Undecided, 4-Agree, 5-Strongly Agree), with a score ranging from 21 to 105.

The questionnaire consisted of 3 subscales:

The higher the combined score on the SSS, the higher the level of sexual satisfaction.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Statistical analysis was performed using STATISTICA 13.0 (StatSoft, Cracow, Poland). A

SAMPLE SIZE CALCULATION:

To determine the minimum number of participants in the study, we used the statistical tool available at https://www.naukowiec.org/dobor.html (accessed December 31, 2022) [28] and https://www.statystyka.az.pl/dobor/kalkulator-wielkosci-proby.php (accessed December 31, 2022) [29]. Assuming a relative error rate of 7% (the level used in meta-analysis studies) and assuming that the problem of degenerative spinal stenosis could affect 23 334 000, the required number of participants was 165.

Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS WHO QUALIFIED FOR THE HEMILAMINECTOMY:

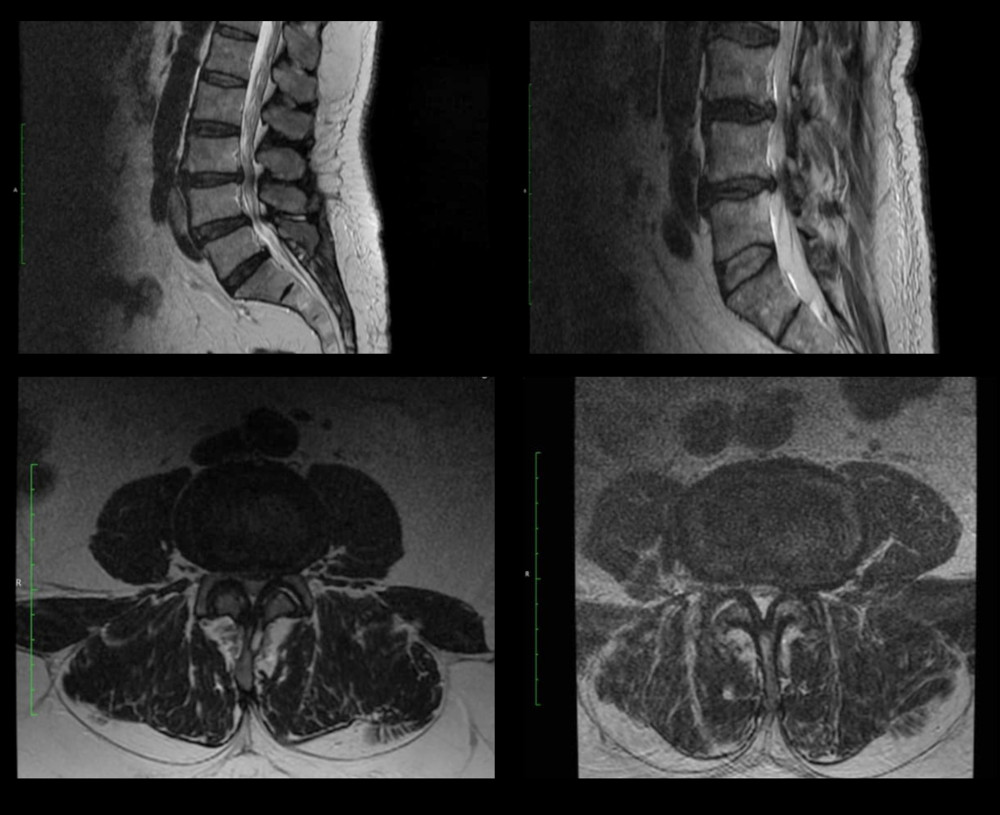

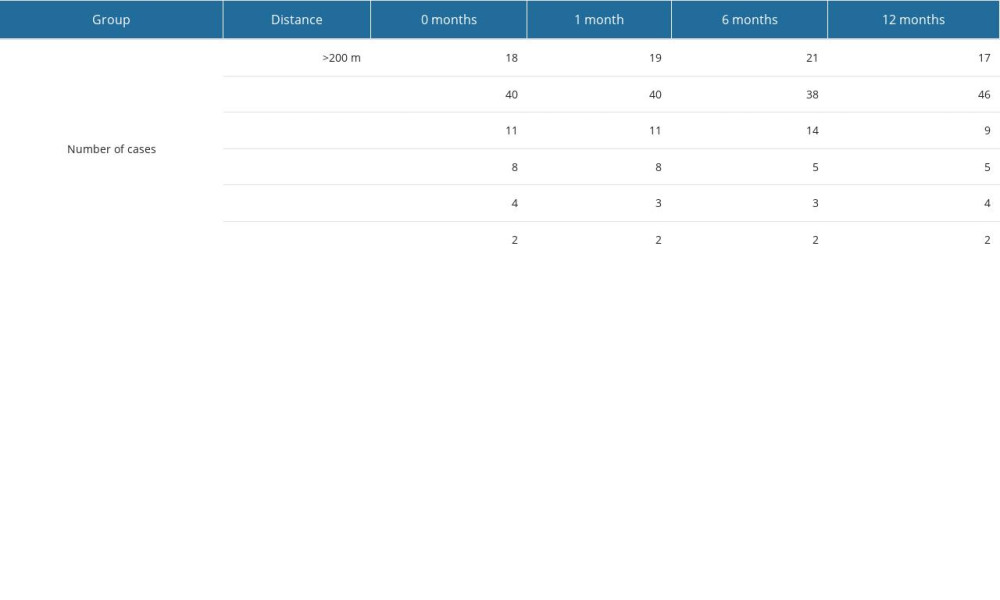

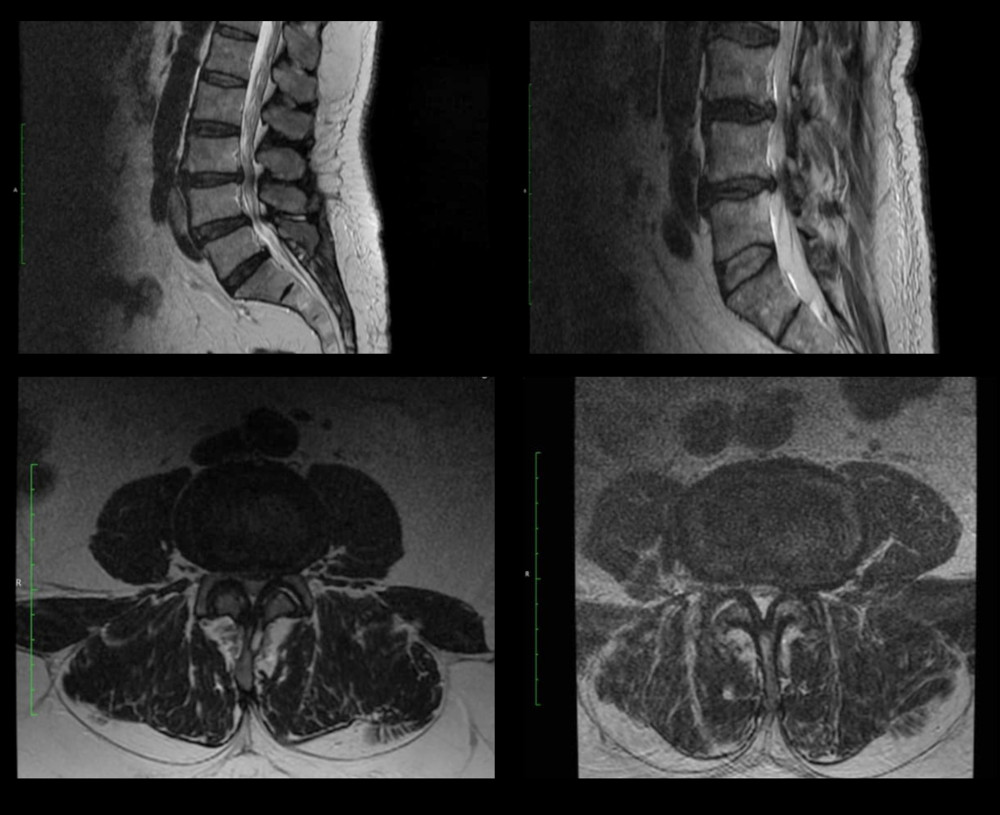

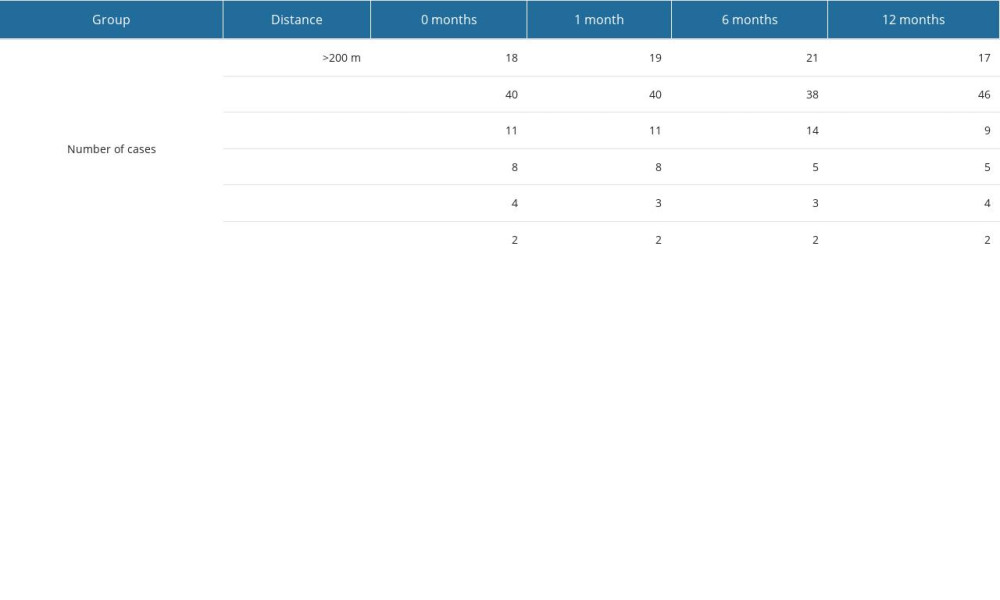

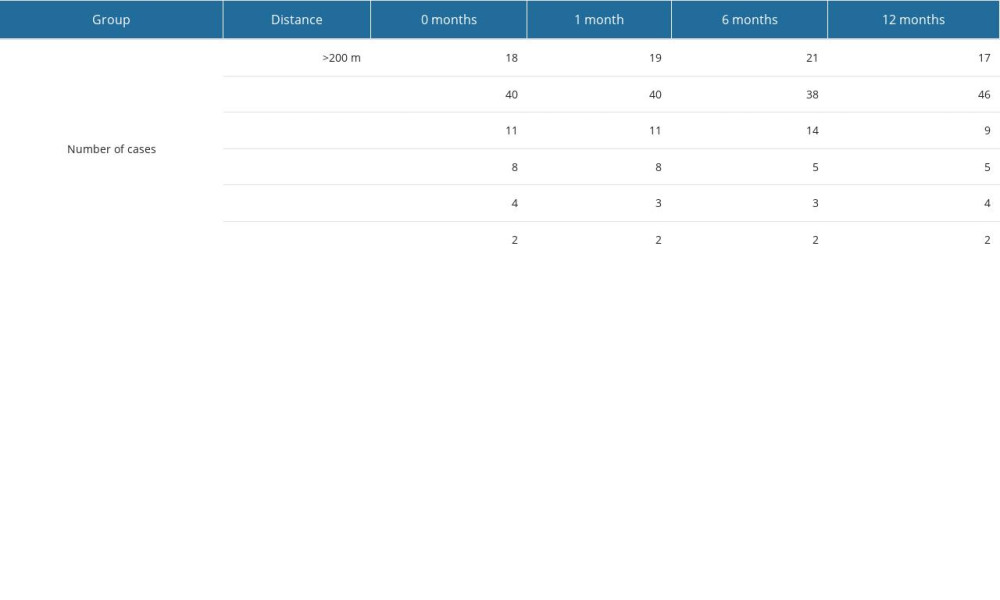

Indications for neurosurgical treatment were the occurrence of lower extremity paresis (16 patients, 17%), worsening of pain (96 patients, 100%), lower extremity fatigue after minor exertion (89 patients, 93%), fatigue after walking a short distance (94 patients, 98%), and narrowing of the lumen of the spinal canal to less than 11 mm on MRI (1.5 T; 96 patients, 100%; Figure 1). The average duration of symptom exacerbation before the decision for surgical treatment was 9±2 months. Table 3 shows the changes in the distance that patients in this group were able to walk alone without resting during the 12-month followup period.

CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS WHO QUALIFIED FOR THE CONSERVATIVE TREATMENT:

According to the recommendations, patients in this group received local and systemic analgesic treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and myorelaxants. Pharmacological treatment included the use of analgesics containing the active substances nimesulide, ketoprofen, diclofenac, acemetacin, and myorelaxants, such as tolperisone hydrochloride, tizanidine, and baclofen. Pain therapy has always been individually selected for each patient, taking into account the patient’s clinical condition and the intensity of the pain, by an experienced doctor. Pharmacotherapy for spinal pain was conducted in accordance with the principles of the analgesic ladder [30,31]. Table 4 shows the changes in the distance that patients in the conservative-treatment group were able to walk alone without resting during the 12-month followup period.

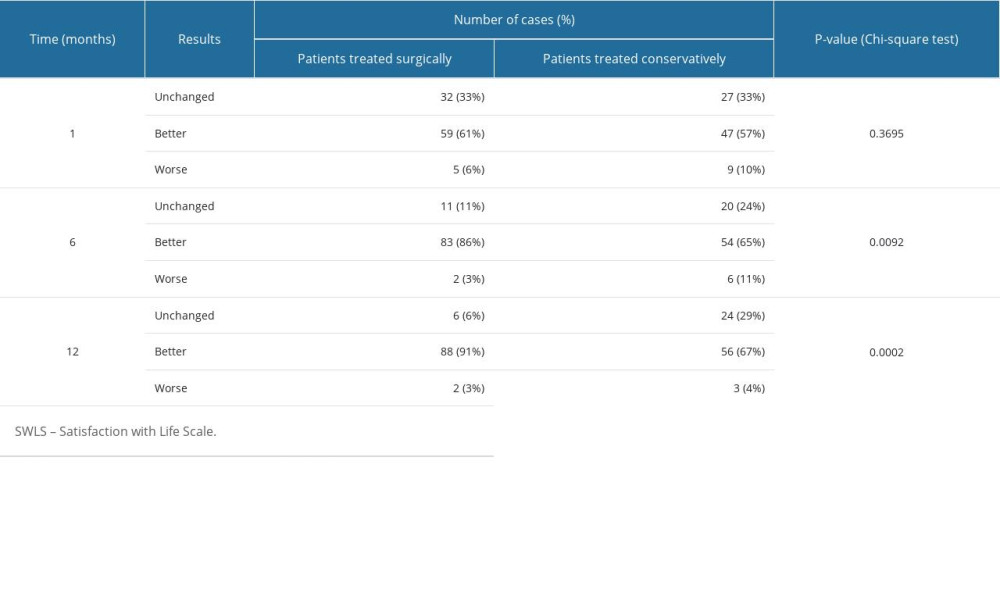

SATISFACTION WITH LIFE SCALE ASSESSMENT IN THE PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY DURING THE 12-MONTH FOLLOWUP:

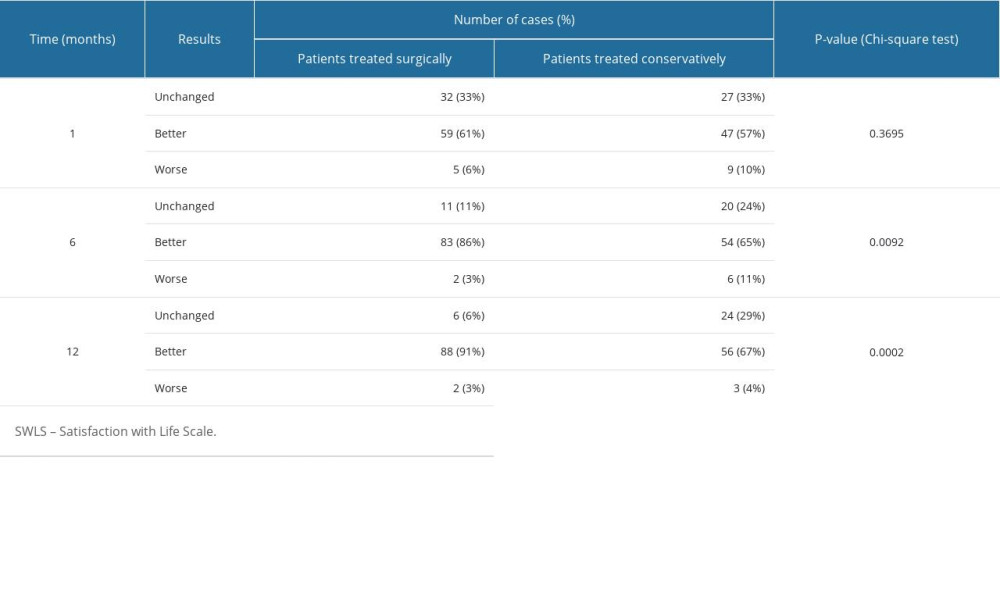

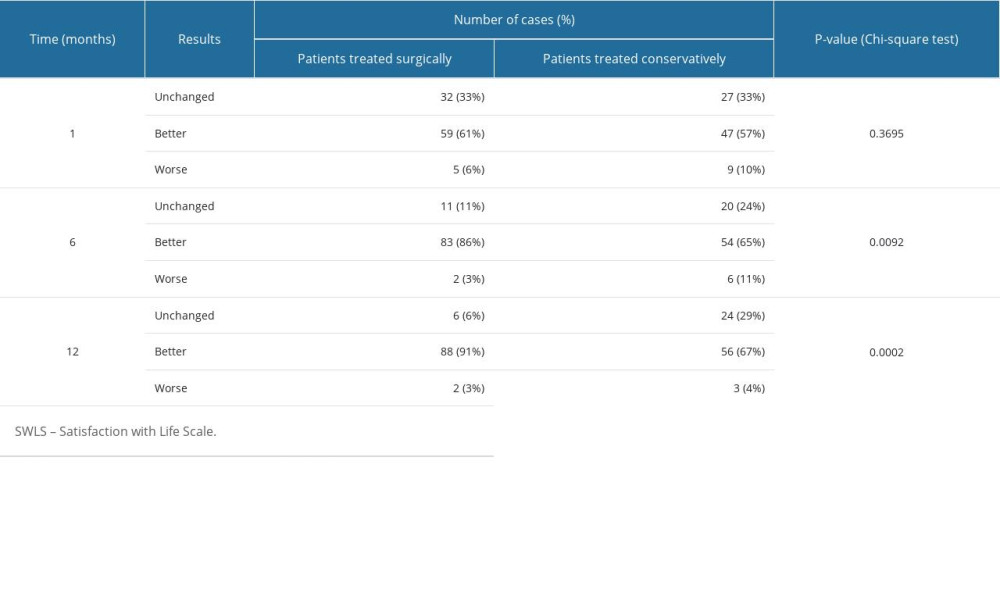

In the group of patients treated surgically, during the first month of followup, most patients (61%) declared an improvement compared with the preoperative period. In 33% of the cases, patients subjectively reported no change. Only 6% of patients experienced a worsening of their health. At the 6-month followup, there was an increase in the percentage of patients who perceived an improvement in health (86%), with a simultaneous decrease in the percentage of patients declaring no improvement (11%) or worsening (3%). At the 12-month followup, 91% of the patients reported an improvement in quality of life after hemilaminectomy. The percentage of patients declaring no improvement after the procedure also decreased (6%).

In the group of patients treated conservatively, in the first month of followup, improvement was declared by 57% of patients, no improvement by 33% of patients, and deterioration of quality of life by 10% of patients. At the 6-month observation, improvement in quality of life was declared by 65% of patients, lack of improvement was declared by almost every fourth patient (24%), and deterioration by 11% of patients. However, the largest number of patients declared an improvement in quality of life (67%) at the 12-month observation, although the percentage of patients experiencing no improvement increased to 29%.

A chi-square test analysis of correlations showed the presence of statistically significant relationships between patients’ quality of life and the time since the end of treatment (at the 6-month followup, P=0.0092; at the 12-month followup, P=0.0002). Thus, statistical analysis showed that both conservative and surgical treatment affected patients’ quality of life, although changes in quality of life were noticeable only after 6 months (statistically significant by chi-square analysis). Detailed results of the SWLS survey are shown in Table 5.

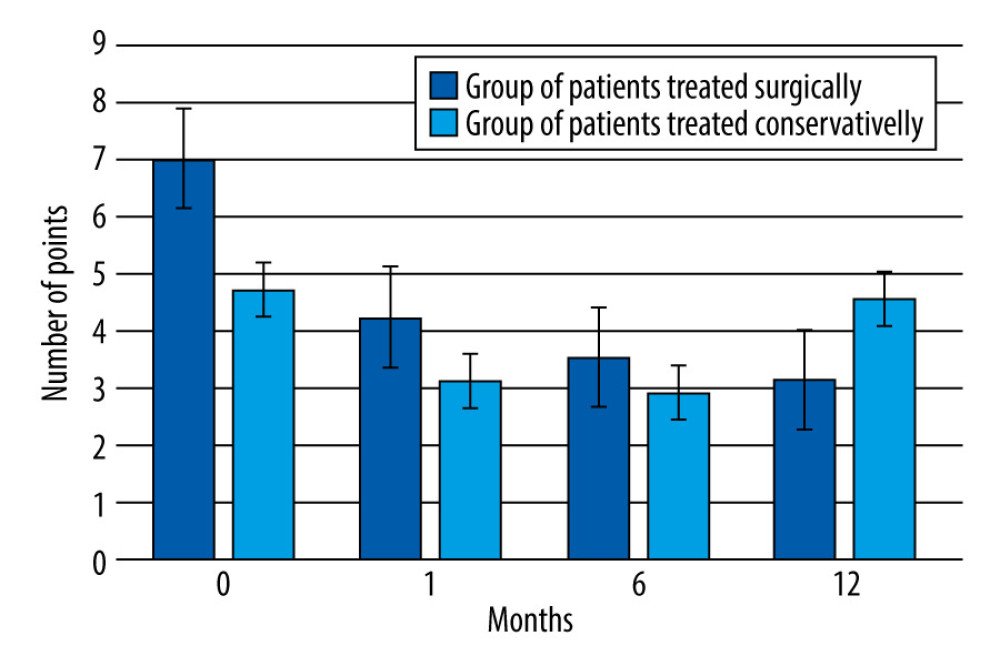

EVALUATION OF PAIN LEVELS IN THE PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY DURING THE 12-MONTH FOLLOWUP:

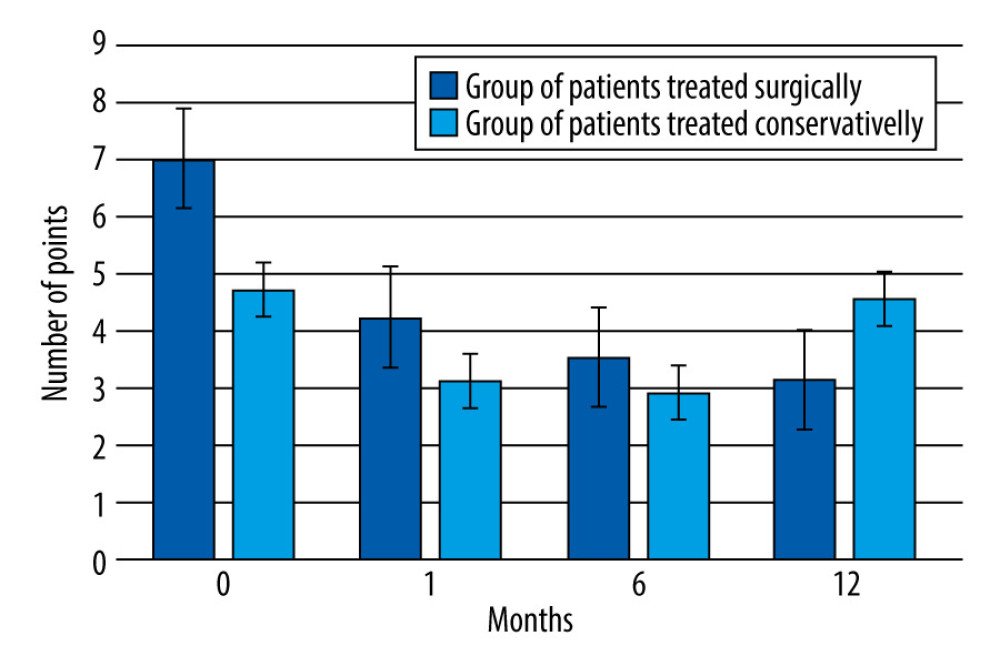

At the start of observation (month 0), the pain level in the group of patients treated surgically was significantly higher than in the group of patients treated conservatively (7.02±0.56 vs 4.71±0.97;

A one-way ANOVA showed a significant change in the level of pain sensation in both groups during the 12-month followup period (P<0.05). Tukey’s post hoc test indicated that statistically significant differences in each group existed between all periods (0 months vs 1 month: P<0.05; 0 months vs 6 months: P<0.05; 0 months vs 12 months: P<0.05; 1 month vs 6 months: P<0.05; 1 month vs 12 months: P<0.05; 6 months vs 12 months: P<0.05). Figure 2 shows the VAS values in the surgery and conservative-treatment groups during the 12 months of followup.

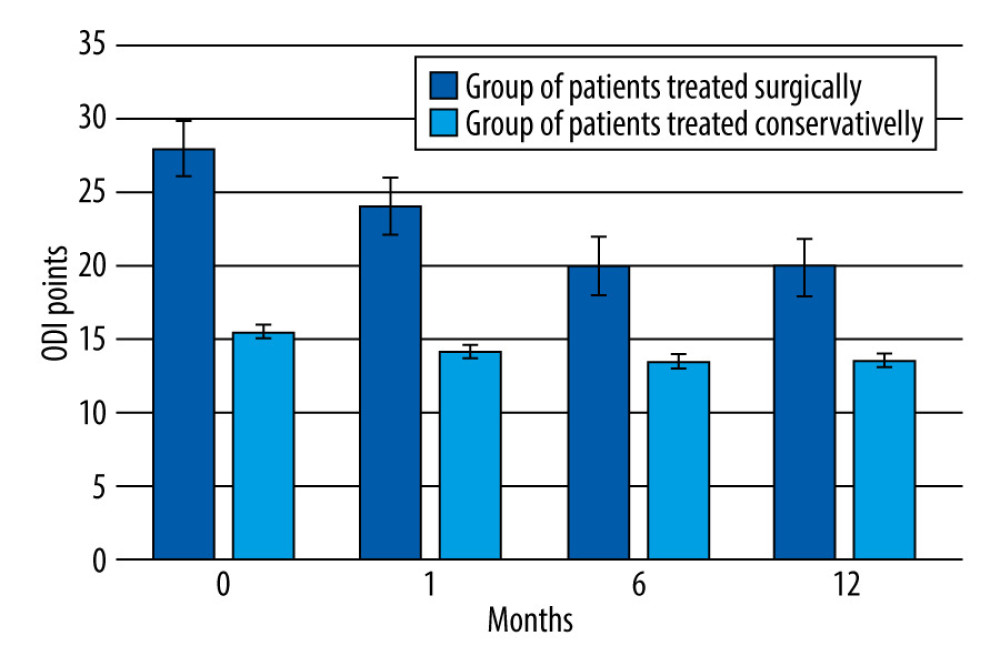

RESULTS OF THE OSWESTRY LOW BACK PAIN DISABILITY QUESTIONNAIRE IN THE PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY:

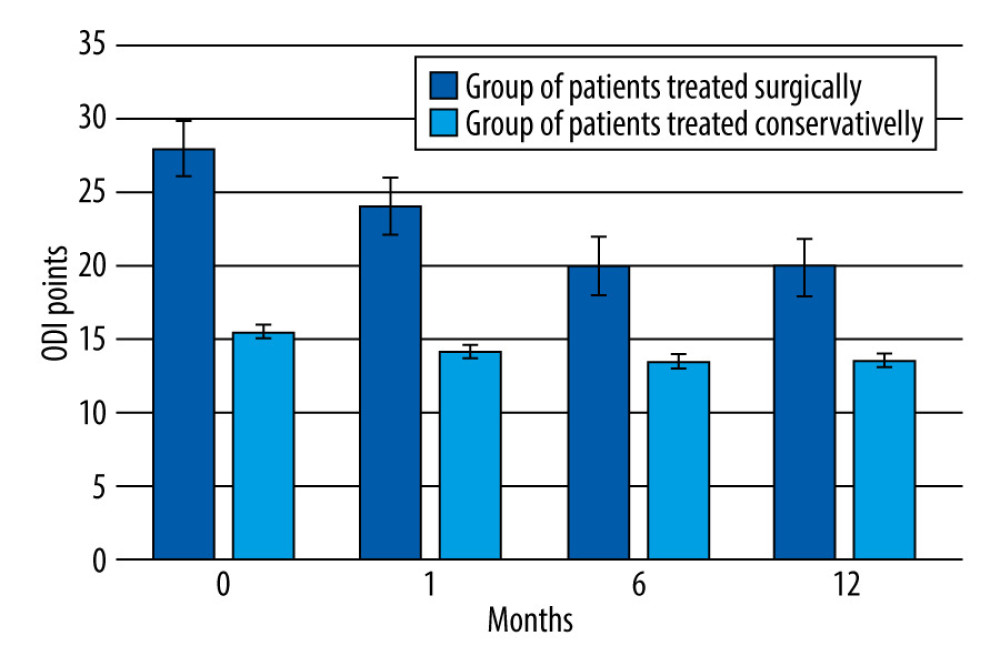

We assessed the degree of disability in both groups using the ODI questionnaire. Statistical analysis showed a statistically significantly higher score in the group of patients who qualified for surgical treatment than in the group of patients who qualified only for conservative treatment, at baseline (27.98±4.58 vs 15.54±2.97;

We also evaluated the changes in ODI questionnaire scores in both groups during the 12-month followup period, noting a statistically significant spike in scores in both groups (ANOVA;

However, in the group of patients treated conservatively, Tukey’s post hoc test showed a statistically significant decrease in scores between 0 and 1 month (P<0.05), 0 and 6 months (P<0.05), 0 and 12 months (P<0.05), and 1 and 12 months (P<0.05). By contrast, the decreases in ODI questionnaire scores between 1 and 6 months (14.19±2.44 vs 13.54±1.77; P=0.238) and between 6 and 12 months (13.54±1.77 vs 13.65±3.11; P=0.652) were not statistically significant. Figure 3 shows the ODI values in the surgery and conservative-treatment groups during the 12 months of followup.

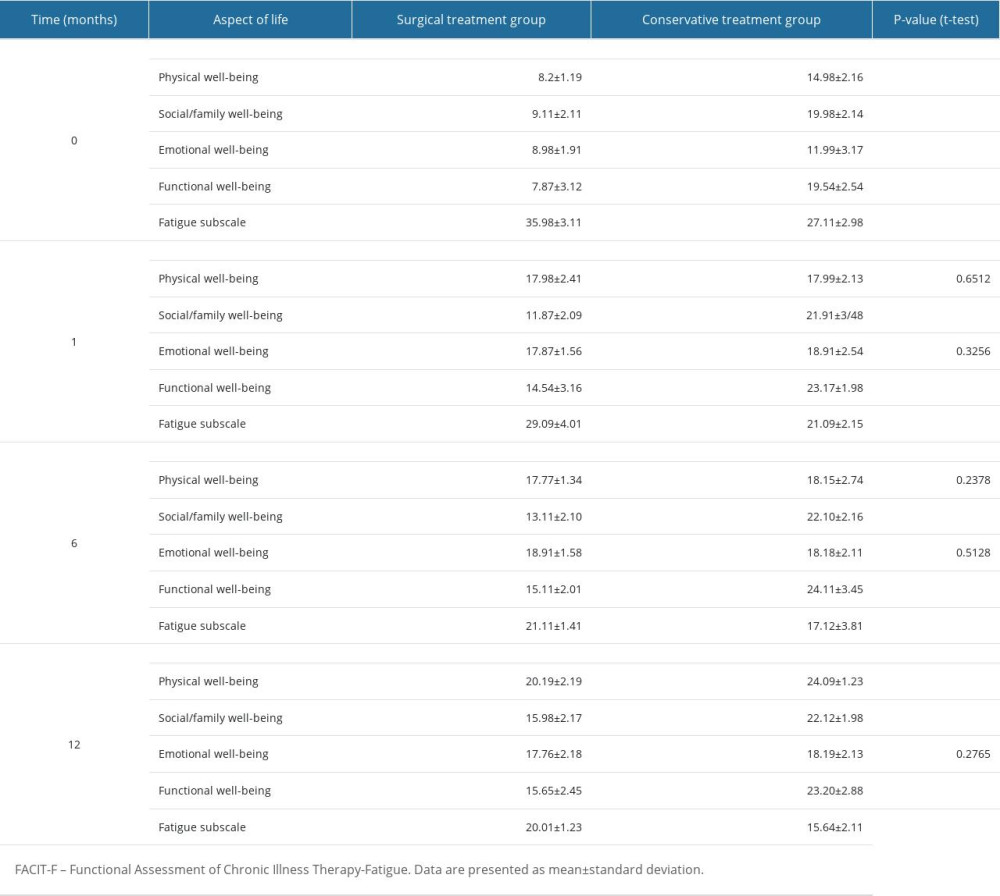

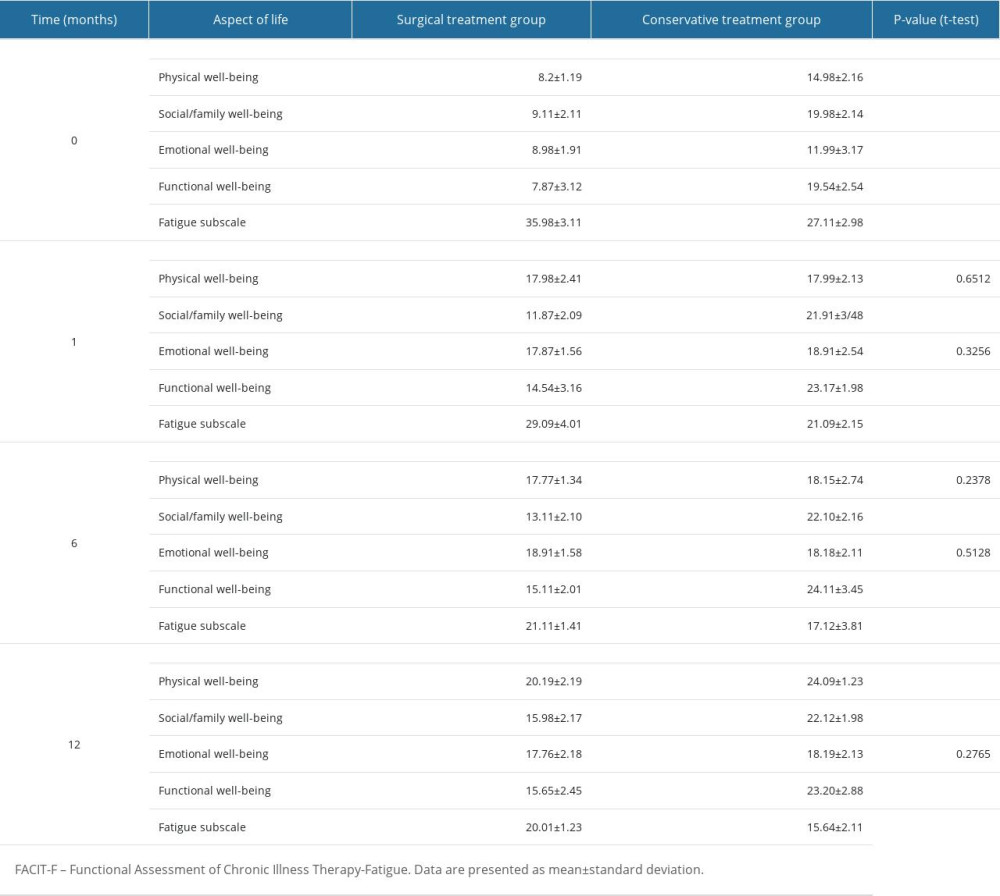

FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENT OF CHRONIC ILLNESS THERAPY-FATIGUE IN THE PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY:

Comparing the total points obtained in the FACIT-F questionnaire, as well as points scored in each of the 4 aspects analyzed, we noted a lower number of points obtained by the patients qualified for the hemilaminectomy, compared with the group of patients treated conservatively, in each period of observation, and this difference was statistically significant for the most part (P<0.05 [t-test]). A value of less than 80 points, indicating an overall reduction in quality of life [19], was found only in the group of patients qualified to the hemilaminectomy at the beginning of the followup (0 months). Based on the fatigue subscale score (>26 points) [19], chronic fatigue was seen at the start of followup (0 month) and in the first month after surgery. In the group of patients qualified for the hemilaminectomy, at the start of followup (0 months), based on the interpretive criteria [19], we found that osteoarthritis had a negative impact on all of the assessed aspects of life. At 1 and 6 months, we found a negative effect of the disease on social/family well-being in each patient in the study.

An ANOVA showed statistically significant differences in the FACIT-F questionnaire scores for quality of life only in the group of patients qualified for the hemilaminectomy (P<0.05). Tukey’s post hoc test showed statistically significant differences between 0 and 1 month (P<0.05), 0 and 6 months (P<0.05), and 0 and 12 months (P<0.05). Table 6 shows the FACIT-F values in the surgery and conservative-treatment groups during the 12 months of followup.

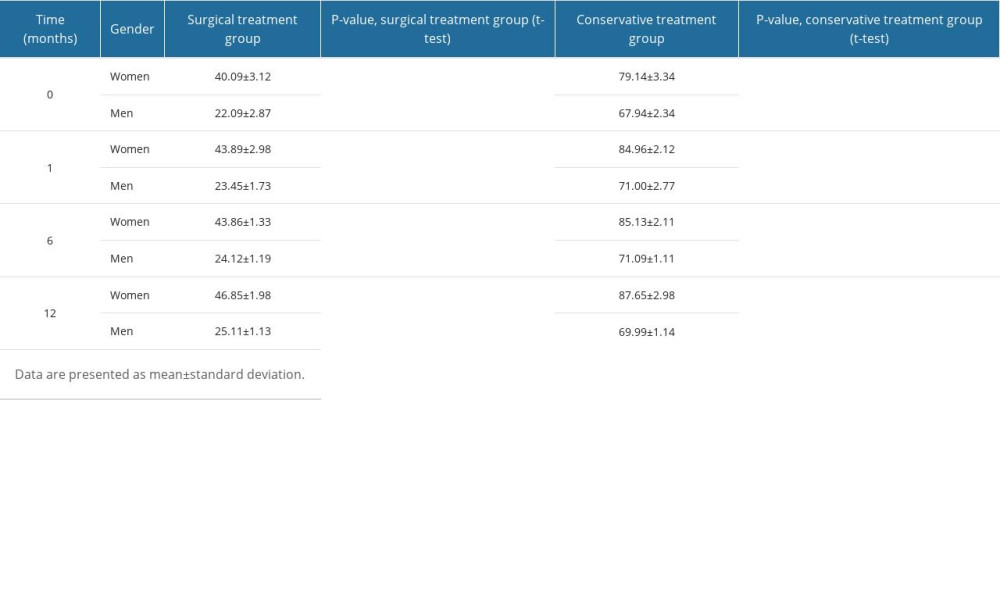

RESULTS OF THE SEXUAL SATISFACTION SCALE IN THE GROUP OF PATIENTS TREATED SURGICALLY AND CONSERVATIVELY:

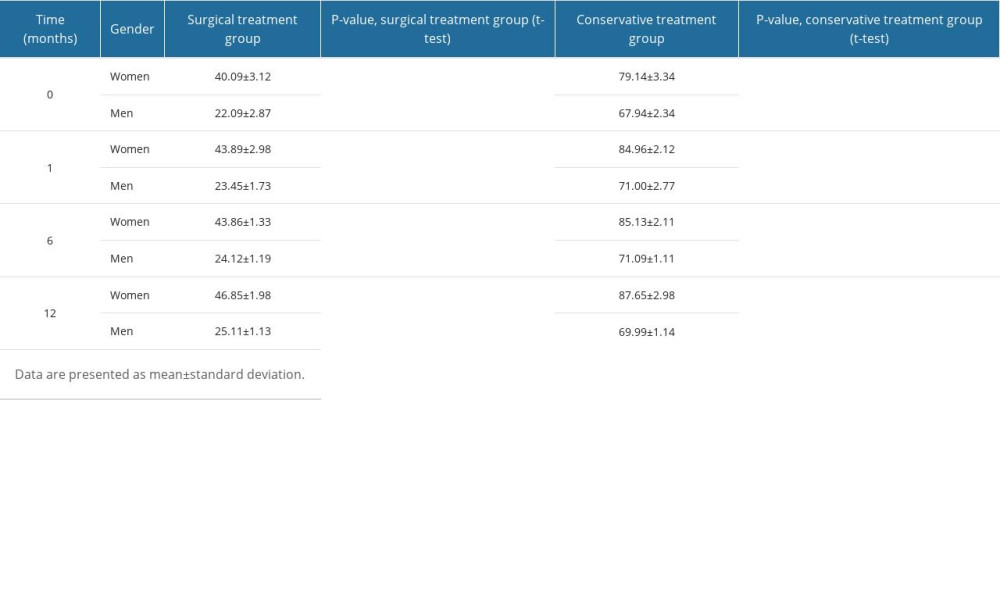

We assessed changes in sexual satisfaction between men and women in both groups. Women in both groups scored higher on the SSS questionnaire than men. We showed that in both groups, the level of sexual satisfaction was significantly higher in women than in men throughout the 12-month observation period (P<0.0001 [t-test]). Further, when we compared the level of sexual satisfaction of men and women between groups, a statistically significantly higher level of sexual satisfaction was declared by participants in the conservative-treatment group (P<0.0001; t-test). A one-way ANOVA did not show that the level of sexual satisfaction for men and women changed significantly during the 12-month followup period (P>0.05). Table 7 shows the SSS values in both groups of patients during the 12 months of followup.

Discussion

The rationale for the analyses presented in our article was based on an analysis conducted by Zaina et al, who, based on a thorough analysis of the literature from 8 databases, concluded that surgical treatment of LSS does not appear to have more benefits than conservative treatment [32]. Further, Machado et al indicated that surgical treatment of LSS has a relative risk of reoperation, regardless of the surgical technique chosen [33].

Our statistical analysis showed that both conservative and surgical treatment affected patients’ quality of life, although changes in quality of life were noticeable only after 6 months. We also noted a reduction in pain expressed on the VAS scale, with the difference being again more significant in the group of patients undergoing hemilaminectomy compared with those treated conservatively. The period of pain reduction was longer in the conservative-treatment group compared with the surgery group, in which, at the 12-month observation, the pain level was similar to that at the baseline. A reduction in the degree of disability was also demonstrated. The results indicate that in the group of patients treated surgically, the procedure fulfilled its role in pain control, contributing to a significant reduction in pain. The hemilaminectomy procedure aims to remove the cause of pain, which may also explain the better results in this group of patients [35].

Puolakka et al compared pain intensity in patients with low back pain before and 2 months after the procedure and found a significant reduction in pain intensity in the case of pain in the limb. However, the pain in the spine did not decrease during followup [36]. Dagistan et al, in a group of LSS patients smaller than our sample, found that performing surgical intervention significantly reduced pain and disability among patients, which positively correlated with an improved quality of life [37].

Pennington et al assessed the quality of life, pain intensity, and degree of disability in 3 groups of patients with clinical and radiographic evidence of tandem spinal stenosis: 1) those who underwent lumbar decompression only, 2) those who underwent cervical and lumbar decompression, and 3) those who underwent conservative management only [38]. Similar to our findings, they showed that the surgical group improved more than the conservatively treated group [38]. This may be because patients treated conservatively, unless due to refusal of surgical treatment, have less advanced LSS and, as a rule, less pain and impaired mobility [38].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first analysis of its kind in degenerative LSS. Studies using the FACIT-F questionnaire assess the functional status and quality of life of chronically ill patients, regardless of the disease [40]. We showed that the disease affected all 4 assessed aspects of life among patients requiring surgical intervention, with the effect of LSS on fatigue being at the borderline of the criteria. Notably, in the group of patients treated surgically, at the 6-month observation, we found a reduction in the quality of life in social/family well-being, suggesting that the quality of life assessment should be carried out using various questionnaires to obtain the most objective picture of changes [41].

Based on the available literature, we found a lack of research analyzing sexual satisfaction among LSS patients, which affects the sense and perception of life satisfaction [42]. In our study, we also decided to assess how much LSS affected sexual satisfaction before and after treatment. Indeed, the patients were at perimenopausal and postmenopausal ages, which does not mean that sexual activity was abandoned in this age group [42]. We showed a lower level of sexual satisfaction in the group of patients treated surgically compared with the group treated conservatively. We also showed that in both groups, the level of sexual satisfaction was significantly higher in women than in men throughout the 12-month observation period. Berg et al showed that in the group of 152 patients with chronic low back pain, the pain affected sexual life in 34% of the patients, and in 30% of the patients, the effect was considerable [43].

Jens et al assessed the quality of life, pain level, and erectile dysfunction in a group of 197 men with LSS who underwent surgery [44]. Although there was an improvement in quality of life and a reduction in pain, there was an increase in erectile dysfunction after surgery [44]. Wottrich et al assessed the effect of cervical and lumbar decompression surgery on erectile dysfunction [45] and found that surgical intervention did not significantly contribute to the reduction of erectile dysfunction [45].

The analysis presented in the present study has several advantages, including the use of standardized questionnaires, which allowed us to objectively assess quality of life, degree of disability, and sexual satisfaction. Further, both of the groups were homogeneous; that is, all patients in the surgery group had the same neurosurgical procedure, which involved the same medical and nursing team, and all patients of both groups received the same rehabilitation at equal intervals. The assessment of the severity of degenerative changes was always performed independently by 2 neurosurgeons, and the MRI examination was performed on an apparatus with an electromagnetic field strength of 1.5 T. Necessary for the reliability of the results is the fact that the study participants had unlimited time to fill out the questionnaires and the opportunity to ask questions when any of the questions or statements were incomprehensible to them.

Nevertheless, this study also has weaknesses. First, the study presents the results obtained from a single research center. A second limitation is the small sample size; it would be valuable for the reliability of the results to increase the size of the groups. Third, including patients with more similar characteristics in terms of pain and stenosis severity in the 2 groups would perhaps allow even more objective results to be obtained. However, it is not possible to obtain such groups, since surgical treatment is recommended in cases where lesions are more radiologically advanced and neurological losses are present. Lastly, the observation period of the study was only 12 months. Future studies should consider expanding the period of observation.

Conclusions

The findings show that both conservative and surgical treatments had a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. The majority of patients in both groups declared an improvement in their quality of life after surgery, with the hemilaminectomy group showing a higher percentage of responses that their quality of life had improved. Based on the results obtained from the FACIT-F questionnaire, we showed that in the group of patients qualified for surgery, LSS had a non-root effect on the patients’ lives. Nevertheless, 6 months after the surgery, the patients’ quality of life was satisfactory. The analysis showed a reduction in pain and disability in both groups of patients, indicating the effectiveness of both treatment options. Nonetheless, it seems that performing surgery has a longer-lasting effect in terms of pain reduction. We showed that women in both groups declared significantly lower satisfaction than men throughout the followup period. Despite some limitations of the study, the results obtained are clinically relevant.

Figures

Figure 1. Sample MRI images of the lumbosacral spine of patients enrolled in the hemilaminectomy group, before surgical decompression.

Figure 1. Sample MRI images of the lumbosacral spine of patients enrolled in the hemilaminectomy group, before surgical decompression.  Figure 2. Change in pain intensity in the patients treated surgically and conservatively, over the 12-month followup period.

Figure 2. Change in pain intensity in the patients treated surgically and conservatively, over the 12-month followup period.  Figure 3. Change in the degree of disability (Oswestry disability index questionnaire) in the patients treated surgically and conservatively, over the 12-month followup period.

Figure 3. Change in the degree of disability (Oswestry disability index questionnaire) in the patients treated surgically and conservatively, over the 12-month followup period. Tables

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for hemilaminectomy. Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for conservative treatment.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for conservative treatment. Table 3. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the hemilaminectomy could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation.

Table 3. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the hemilaminectomy could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation. Table 4. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the conservative treatment could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation.

Table 4. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the conservative treatment could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation. Table 5. Results of the SWLS survey, assessing quality of life, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 5. Results of the SWLS survey, assessing quality of life, in patients treated surgically and conservatively. Table 6. Results of the FACIT-F survey, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 6. Results of the FACIT-F survey, in patients treated surgically and conservatively. Table 7. Changes in sexual satisfaction results, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 7. Changes in sexual satisfaction results, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

References

1. Dowlati E, Mualem W, Black J, Should asymptomatic cervical stenosis be treated in the setting of progressive thoracic myelopathy? A systematic review of the literature: Eur Spine J, 2022; 31(2); 275-87

2. Feng S, Fan Z, Li X: Combination of intraspine interlaminar device with lumbar discectomy in patients with L5/S1 disc herniation Unpublished preprint posted online in 2020

3. Akar E, Somay H, Comparative morphometric analysis of congenital and acquired lumbar spinal stenosis: J Clin Neurosci, 2019; 68; 256-61

4. Kachonkittisak K, Kunakornsawat S, Pluemvitayaporn T, Congenital spinal canal stenosis with ossification of the ligamentum flavum in an achondroplastic patient: A case report and literature review: Asian J Neurosurg, 2019; 14(4); 1231

5. Verbiest H, Results of surgical treatment of idiopathic developmental stenosis of the lumbar vertebral canal. A review of twenty-seven years’ experience: J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1977; 59(2); 181-88

6. Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R, The epidemiology of low back pain: Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 2010; 24(6); 769-81

7. Bydon M, Alvi MA, Goyal A, Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: Definition, natural history, conservative management, and surgical treatment: Neurosurg Clin N Am, 2019; 30(3); 299-4

8. Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, Computed tomography-evaluated features of spinal degeneration: Prevalence, intercorrelation, and association with self-reported low back pain: Spine J, 2010; 10(3); 200-8

9. Hilibrand AS, Rand N, Degenerative lumbar stenosis: Diagnosis and management: J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 1999; 7(4); 239-49

10. Gandhi J, Shah J, Joshi G, Neuro-urological sequelae of lumbar spinal stenosis: Int J Neurosci, 2018; 128(6); 554-62

11. : WHOQOL – Measuring quality of life, The World Health Organization https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol

12. Dezutter J, Casalin S, Wachholtz A, Meaning in life: An important factor for the psychological well-being of chronically ill patients?: Rehabil Psychol, 2013; 58(4); 334-41

13. Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica: Spine, 1995; 20(17); 1899-908 discussion 1909

14. de Vries M, Ouwendijk R, Kessels AG, Comparison of generic and disease-specific questionnaires for the assessment of quality of life in patients with peripheral arterial disease: J Vasc Surg, 2005; 41(2); 261-68

15. Pequeno NPF, Cabral NL, de A, Marchioni DM, Quality of life assessment instruments for adults: A systematic review of population-based studies: Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2020; 18(1); 208

16. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S, The satisfaction with life scale: J Pers Assess, 1985; 49(1); 71-75

17. Heller GZ, Manuguerra M, Chow R, How to analyze the visual analogue scale: Myths, truths and clinical relevance: Scand J Pain, 2016; 13; 67-75

18. Roland M, Fairbank J, The Roland-Morris disability questionnaire and the Oswestry disability questionnaire: Spine, 2000; 25(24); 3115-24

19. Webster K, Cella D, Yost K, The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy (FACIT) measurement system: Properties, applications, and interpretation: Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2003; 1; 79

20. Parker SL, Godil SS, Mendenhall SK, Two-year comprehensive medical management of degenerative lumbar spine disease (lumbar spondylolisthesis, stenosis, or disk herniation): A value analysis of cost, pain, disability, and quality of life: Clinical article: J Neurosurg Spine, 2014; 21(2); 143-49

21. Özdemir E, Paker N, Bugdayci D, Tekdos DD, Quality of life and related factors in degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: A controlled study: J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil, 2015; 28(4); 749-53

22. Bello F, Njami VA, Bogne SL, Quality of life of patients operated for lumbar stenosis at the Yaoundé Central Hospital: Br J Neurosurg, 2020; 34(1); 62-65

23. Ulrich NH, Burgstaller JM, Valeri F, Incidence of revision surgery after decompression with vs without fusion among patients with degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: JAMA Netw Open, 2022; 5(7); e2223803

24. Lubkowska W, Krzepota J, Quality of life and health behaviours of patients with low back pain: Phys Act Rev, 2019(7); 182-92

25. Fairbank JC, Why are there different versions of the Oswestry disability index?: A review: J Neurosurg Spine, 2014; 20(1); 83-86

26. Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB, The Oswestry disability index: Spine, 2000; 25(22); 2940-53

27. Meston C, Trapnell P, Development and validation of a five-factor sexual satisfaction and distress scale for women: The sexual satisfaction scale for women (SSS-W): J Sex Med, 2005; 2(1); 66-81

28. : Kalkulator doboru próby https://www.naukowiec.org/dobor.html

29. : Statystyka od A do Z [in Polish]https://www.statystyka.az.pl/dobor/kalkulator-wielkosci-proby.php

30. Jarosz J, Leczenie farmakologiczne bólów kręgosłupa: Lek POZ, 2015; 1(1); 13-20 [in Polish]

31. de Campos TF, Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: Assessment and management NICE Guideline [NG59]: J Physiother, 2017; 63(2); 120

32. Zaina F, Tomkins-Lane C, Carragee E, Negrini S, Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016; 2016(1); CD010264

33. Machado GC, Ferreira PH, Harris IA, Effectiveness of surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis: PLoS One, 2015; 10(3); e0122800

34. Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM, Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances: The Lancet, 2021; 397(10289); 2082-2097, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00393-7

35. Rizzo RRN, Ferraro MC, Wewege MA, Efficacy and safety of medicines targeting neurotrophic factors in the management of low back pain: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis: JMIR Res Protoc, 2021; 10(1); e22905

36. Puolakka K, Ylinen J, Neva MH, Kautiainen H, Häkkinen A, Risk factors for back pain-related loss of working time after surgery for lumbar disc herniation: A 5-year follow-up study: Eur Spine J, 2008; 17(3); 386-92

37. Dagistan Y, Dagistan E, Gezici AR, Effects of minimally invasive decompression surgery on quality of life in older patients with spinal stenosis: Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2015; 139; 86-90

38. Pennington Z, Alentado VJ, Lubelski D, Quality of life changes after lumbar decompression in patients with tandem spinal stenosis: Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2019; 184; 105455

39. Tagliaferri SD, Miller CT, Owen PJ, Domains of chronic low back pain and assessing treatment effectiveness: A clinical perspective: Pain Pract, 2020; 20(2); 211-25

40. Wagan AA, Raheem A, Bhatti A, Zafar T, Fatigue in psoriatic arthritis: Is it related to disease activity?: Pak J Med Sci, 2021; 37; 1025-30

41. Ferretti F, Coluccia A, Gusinu R, Quality of life and objective functional impairment in lumbar spinal stenosis: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of moderators: BMJ Open, 2019; 9(11); e032314

42. Harder H, Starkings RML, Fallowfield LJ, Sexual functioning in 4,418 postmenopausal women participating in UKCTOCS: A qualitative free-text analysis: Menopause NYN, 2019; 26(10); 1100-9

43. Berg S, Fritzell P, Tropp H, Sex life and sexual function in men and women before and after total disc replacement compared with posterior lumbar fusion: Spine J, 2009; 9(12); 987-94

44. Gempt J, Rothoerl RD, Grams A, Effect of lumbar spinal stenosis and surgical decompression on erectile function: Spine, 2010; 35(22); E1172

45. Wottrich S, Kha S, Thompson N, The effect of cervical and lumbar decompression surgery for spinal stenosis on erectile dysfunction: Global Spine J, 2022 [Online ahead of print]

Figures

Figure 1. Sample MRI images of the lumbosacral spine of patients enrolled in the hemilaminectomy group, before surgical decompression.

Figure 1. Sample MRI images of the lumbosacral spine of patients enrolled in the hemilaminectomy group, before surgical decompression. Figure 2. Change in pain intensity in the patients treated surgically and conservatively, over the 12-month followup period.

Figure 2. Change in pain intensity in the patients treated surgically and conservatively, over the 12-month followup period. Figure 3. Change in the degree of disability (Oswestry disability index questionnaire) in the patients treated surgically and conservatively, over the 12-month followup period.

Figure 3. Change in the degree of disability (Oswestry disability index questionnaire) in the patients treated surgically and conservatively, over the 12-month followup period. Tables

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for hemilaminectomy.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for hemilaminectomy. Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for conservative treatment.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for conservative treatment. Table 3. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the hemilaminectomy could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation.

Table 3. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the hemilaminectomy could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation. Table 4. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the conservative treatment could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation.

Table 4. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the conservative treatment could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation. Table 5. Results of the SWLS survey, assessing quality of life, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 5. Results of the SWLS survey, assessing quality of life, in patients treated surgically and conservatively. Table 6. Results of the FACIT-F survey, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 6. Results of the FACIT-F survey, in patients treated surgically and conservatively. Table 7. Changes in sexual satisfaction results, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 7. Changes in sexual satisfaction results, in patients treated surgically and conservatively. Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for hemilaminectomy.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for hemilaminectomy. Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for conservative treatment.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for conservative treatment. Table 3. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the hemilaminectomy could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation.

Table 3. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the hemilaminectomy could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation. Table 4. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the conservative treatment could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation.

Table 4. Changes in the distance that patients who qualified for the conservative treatment could walk without taking a break, over the 12 months of observation. Table 5. Results of the SWLS survey, assessing quality of life, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 5. Results of the SWLS survey, assessing quality of life, in patients treated surgically and conservatively. Table 6. Results of the FACIT-F survey, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 6. Results of the FACIT-F survey, in patients treated surgically and conservatively. Table 7. Changes in sexual satisfaction results, in patients treated surgically and conservatively.

Table 7. Changes in sexual satisfaction results, in patients treated surgically and conservatively. In Press

05 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Role of Critical Shoulder Angle in Degenerative Type Rotator Cuff Tears: A Turkish Cohort StudyMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943703

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Outcomes between Single-Level and Double-Level Corpectomy in Thoracolumbar Reconstruction: A ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943797

21 Mar 2024 : Meta-Analysis

Economic Evaluation of COVID-19 Screening Tests and Surveillance Strategies in Low-Income, Middle-Income, a...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943863

10 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Predicting Acute Cardiovascular Complications in COVID-19: Insights from a Specialized Cardiac Referral Dep...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942612

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952