29 December 2022: Database Analysis

A Systematic Review of Publications Using the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) to Monitor Education in Medical Colleges in Saudi Arabia

Manea M. Al-AhmariACE, Mohammed M. Al MoaleemACEF, Razan Ahmad KhudhayrBG, Athar Ali SulailyBG, Balqees Ahmed M. AlhazmiBG, Mousa Ismail S. AlAliliBG, Abdulrahman Mushabbab AlqahtaniBG, Haya Sultan N. AlassafBG, Imtinan Ahmed Madkhali, Asma Mohammed ShagagiBG, Ibtisam Mohammed MasoudBG, Ali Mohammed RizqBGDOI: 10.12659/MSM.938987

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e938987

Abstract

BACKGROUND: This systematic review aimed to identify and evaluate publications using the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) and its domains, genders, and educational level (EL) to monitor the education environment in medical colleges (MCs), applied medical science colleges (AMSCs), and dental colleges (DCs) in Saudi Arabia (SA).

MATERIAL AND METHODS: A literature search was performed using PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Wiley Library, and Web of Science database keywords and medical, applied medical science, dental colleges headings, followed by a summary and analysis of results. We included all related studies that used DREEM as a tool and were published up to 2022. The following information was extracted from the included studies: researcher’s name(s), publication year, overall DREEM, domain, gender, and educational levels.

RESULTS: Among the 40 studies included in this review, 25 papers were conducted in medical colleges, 5 in applied medical science, and 10 in dental colleges. Overall, DREEM scores among all involved colleges were “more positive than negative,” with scores between 101 and 150. In relation to the 5 domains of DREEM, the percentages of medical colleges ranged from 75% to 88% for all domains, whereas it was higher in dental (80% to 90%) in most domains, but considerably lower for applied medical science (50% to 75%). Females had higher DREEM values in dental than medical and applied medical science colleges, whereas educational levels were higher in applied medical science colleges.

CONCLUSIONS: Overall, DREEM scores were more positive than negative and moved in the correct direction among all involved colleges, with varying degrees of significance between genders and educational levels.

Keywords: Gender Identity, Area Health Education Centers, Nursing Education Research, Environmental Health, Environmental Monitoring, Humans, Male, Female, Saudi Arabia, Perception, Surveys and Questionnaires, Educational Status, Educational Measurement, Students, Medical

Background

In recent years, the Saudi government has attempted to expand the healthcare professional education infrastructure in accordance with the Saudi Vision 2030 plan. Of the 28 government universities and 9 private universities in SA [1], 20 government and 5 private universities offer undergraduate health professional programs [2]. Students in professional education programs in SA are supported through free and subsidized programs [3,4].

The educational environment is the academic and social environment of an institution, which affects how students learn [5]. A safe, valued, participatory, and supportive educational environment leads to more interactions [6,7]. An educational environment that respects the choice and voice of students and focuses on the learning of all students makes students more involved in teaching and learning activities [8]. Over the past 50 years, researchers in teaching, learning, and education have attempted to define and measure the health educational environment [9–11]; the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) is almost certainly the most popular inventory used today [7,12]. DREEM has been useful and effective in assessing medical colleges, applied medical science colleges, dental colleges, chiropractic learning, teaching, and educational environments [5,7,12].

In mid-1998, the World Federation for Medical Education made the teaching and learning environment one of the factors used for assessing health education programs [13]. Educators in different health specialties and disciplines often agree that learning, teaching, academic, and clinical educational environment concerns are important factors in health students’ beliefs, knowledge, capabilities, improvement, achievements, and behaviors [7,14]. Evaluation of the educational environment for males and females at various academic levels or teaching phases (preclinical and clinical) is key to assuring high-quality, student-centered programs [5,7,9].

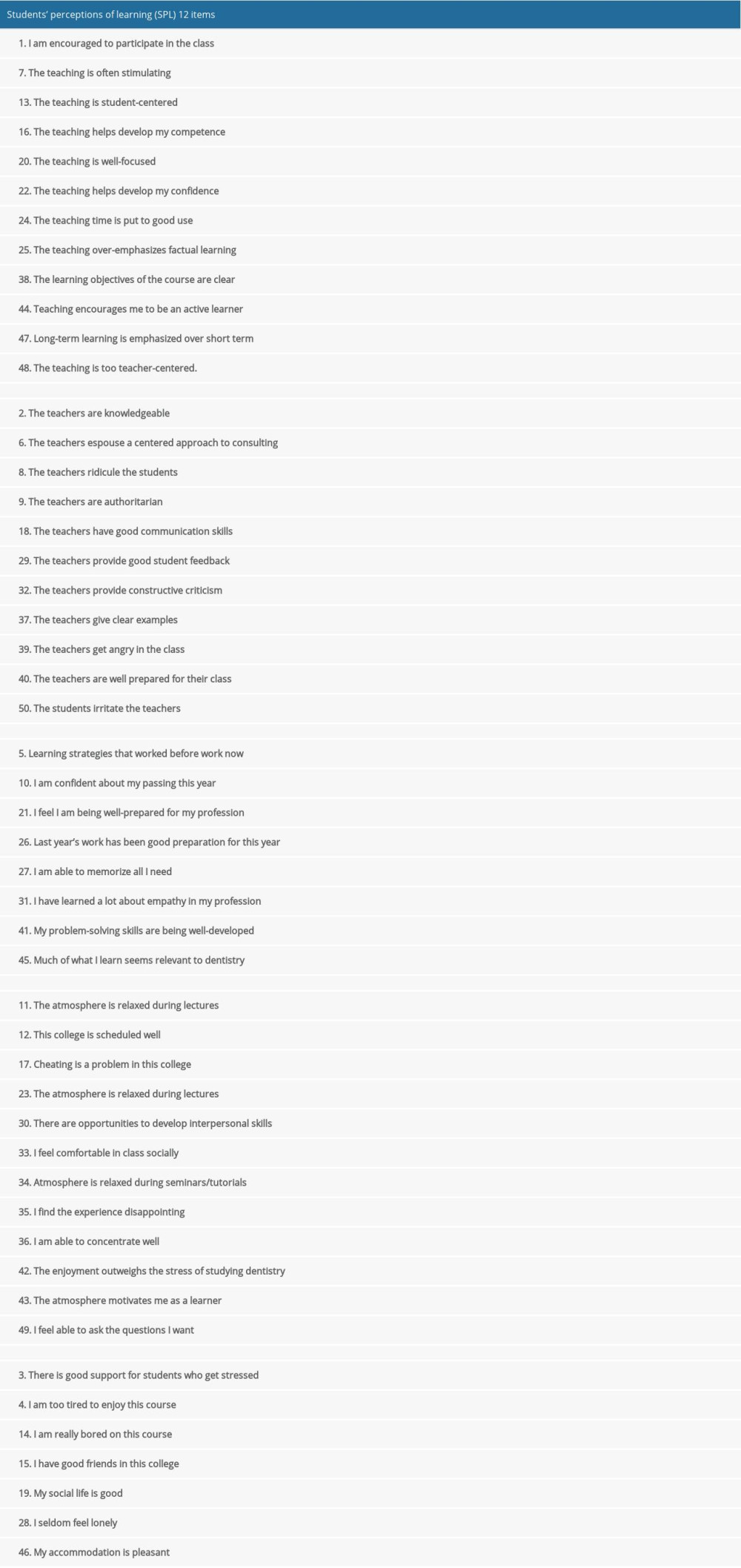

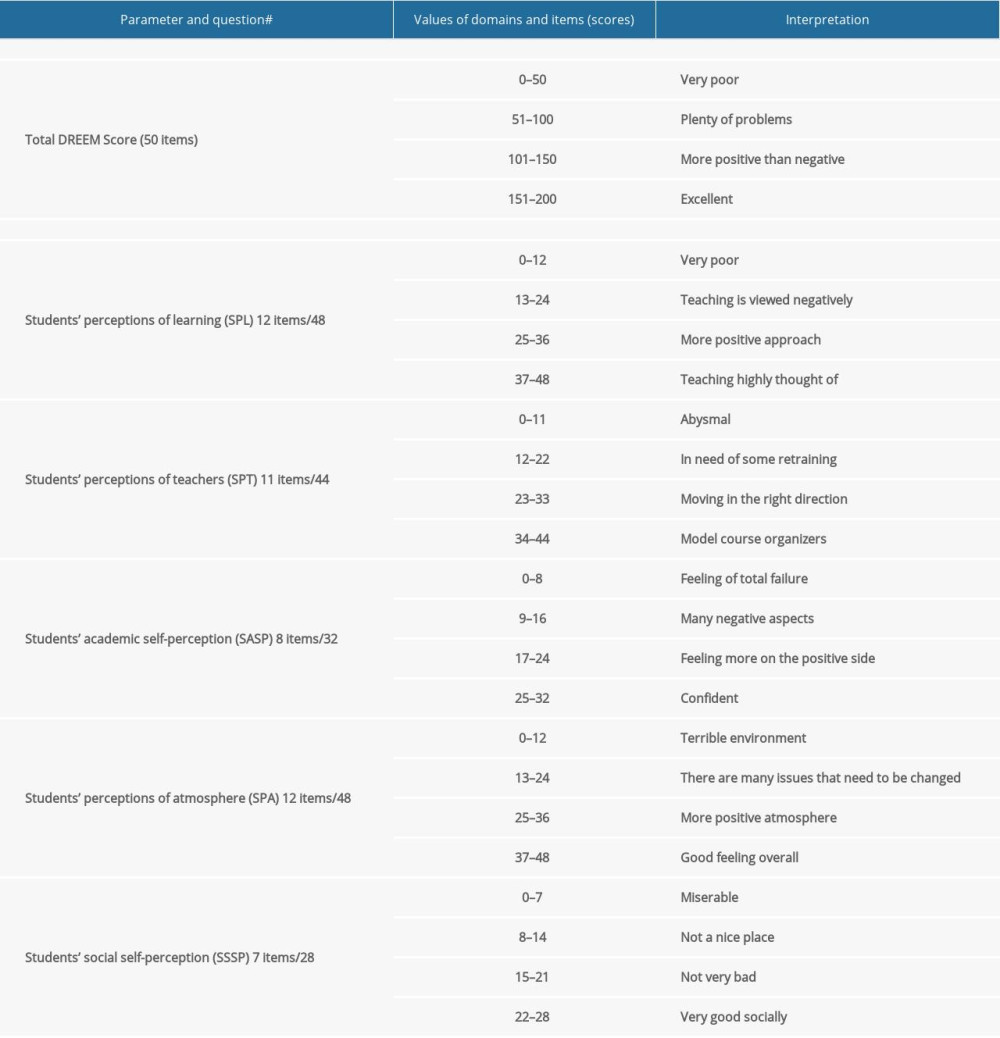

In 1997, Roff et al introduced and developed a suitable instrument with a validation of a universal inventory that measures and assesses the health training settings and medical schools’ environments with a diagnostic tool to evaluate the condition of their school’s teaching and learning environment. This is called the DREEM inventory [7,15]. It is a multidimensional and multicultural tool that can measure the 5 fundamental domains of educational environments, namely, students’ perceptions of learning (SPL), students’ perceptions of teachers (SPT), students’ perceptions of atmosphere (SPA), students’ academic self-perception (SASP), and students’ social self-perception (SSSP) [5,7,12]. DREEM is a 50-item questionnaire that covers a wide range of topics directly relevant to the educational environment (Table 1). It is a closed-ended questionnaire that is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The questionnaire has a maximum score of 200, which indicates the respondent thinks is the ideal educational environments. DREEM was developed by a Delphi panel, and it has been used to highlight the weaknesses and strengths of educational environments in dental colleges, medical colleges, and applied medical science colleges. It has also been translated and copied to many languages, such as Turkish, Romanian, Spanish, Greek, Urdu, and Arabic [16–26]. Table 2 shows how to interpret the overall DREEM score and its 5 domains.

Internationally, not many systematic reviews of DREEM studies have been conducted [15,19,27–30]. Alqahtani (2022) recently published a single systematic review to compare the overall DREEM and domain scores between genders in the educational environment of public and private dental colleges and medical colleges in SA universities [31]. The Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure is a validated tool to evaluate educational environments of all health education setting. This systematic review aimed to identify and evaluate publications using DREEM to monitor the education environment in Saudi Arabian medical, applied medical science, and dental colleges.

Material and Methods

RESEARCH PROTOCOLS AND INCLUSION AND EXCLUSIVE CRITERIA:

The authors created the current search plan by reviewing published papers that used the DREEM inventory to measure educational environment and perceptions in terms of state, context, and population. The research questions were: “What is the overall value of DREEM and its domain scores in medical colleges, applied medical science colleges, and dental colleges in different private and public SA universities, as well as its significance in terms of gender and educational levels or preclinical and clinical phases?” and “Is the overall mean of DREEM and its domains among colleges different in terms of gender and educational level?” Hence, only studies that directly used DREEM on health studies students from different SA cities and were published in English were included. Papers that were published in languages other than English or used indices or inventories other than DREEM to evaluate educational environment were omitted.

SEARCH STRATEGY:

Electronic databases of PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Wiley Library, and Web of Science were searched for relevant papers published up to October 2022. The search terms used were “DREEM inventory,” “educational environments,” “students’ perception,” “DREEM items,” “DREEM domains,” and “Medical, Applied Medical Science, Dental Colleges”, and “Health specialty students in SA.” Keywords were used independently or in combination by using the Boolean operators “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT” to search for the terms “DREEM,” “educational environment,” and “students’ perception” independently. The gray literature was explored using Google Scholar.

STUDY SELECTION:

Two reviewers (F.A. and M.M.AL.) individually assessed articles for eligibility based on inclusion procedures. After duplicates were removed, the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were analyzed for relevance. A third reviewer (B.M.M) studied the validity and repetitions of the papers. Systemic reviews and case reports that did not assess educational environment or students’ perceptions among different health specialties were removed. Published articles that did not indicate the number of participants or whose samples had been relatively anticipated in other studies were also removed. Research that addressed the study questions was deemed relevant. The full text of potentially relevant research was reviewed. The references of the selected published research were checked to see if other studies met the inclusion criteria. In case of a disagreement whether to include an article, a third reviewer (B.M.M) was asked.

DATA EXTRACTION AND ANALYSIS:

Two authors (F.A. and M.M.AL.) summarized significant data from each article using customized tables in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redwood, CA, USA). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third author (B.M.M.). Details included authors’ names, publication year, college type (medical colleges, applied medical science colleges, and dental colleges), university and city names, sample size, response rate (RR), male-to-female ratio, educational levels, and preclinical or clinical phases. Moreover, overall DREEM and domain scores, as well as their interpretations, are presented. Finally, the significance of gender and educational levels was reported.

QUALITY OF INVOLVED PAPERS:

Two authors (F.A. and M.M.AL.) judged the value of included published articles based on the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies [35,36]. Any differences were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached with a third author (B.M.M.). The exterior validity of papers was evaluated through criteria, such as the overall DREEM and domain values and their interpretation, as well as the significance of gender, educational levels, and statistical methods used.

Results

STUDY SELECTION:

The search strategy generated 546 results. A total of 450 articles were excluded because they were duplicates or unrelated to this review. The remaining papers were assessed based on their titles and abstracts. In addition, 56 published articles were removed because they were not conducted in SA (36) or used other indices (20). This review assessed the full text of 40 articles that met all of the inclusion criteria based on predefined eligibility criteria. The included articles used DREEM in 25 medical colleges, 5 applied medical science colleges, and 10 dental colleges. Figure 1 shows how these articles were selected for this review.

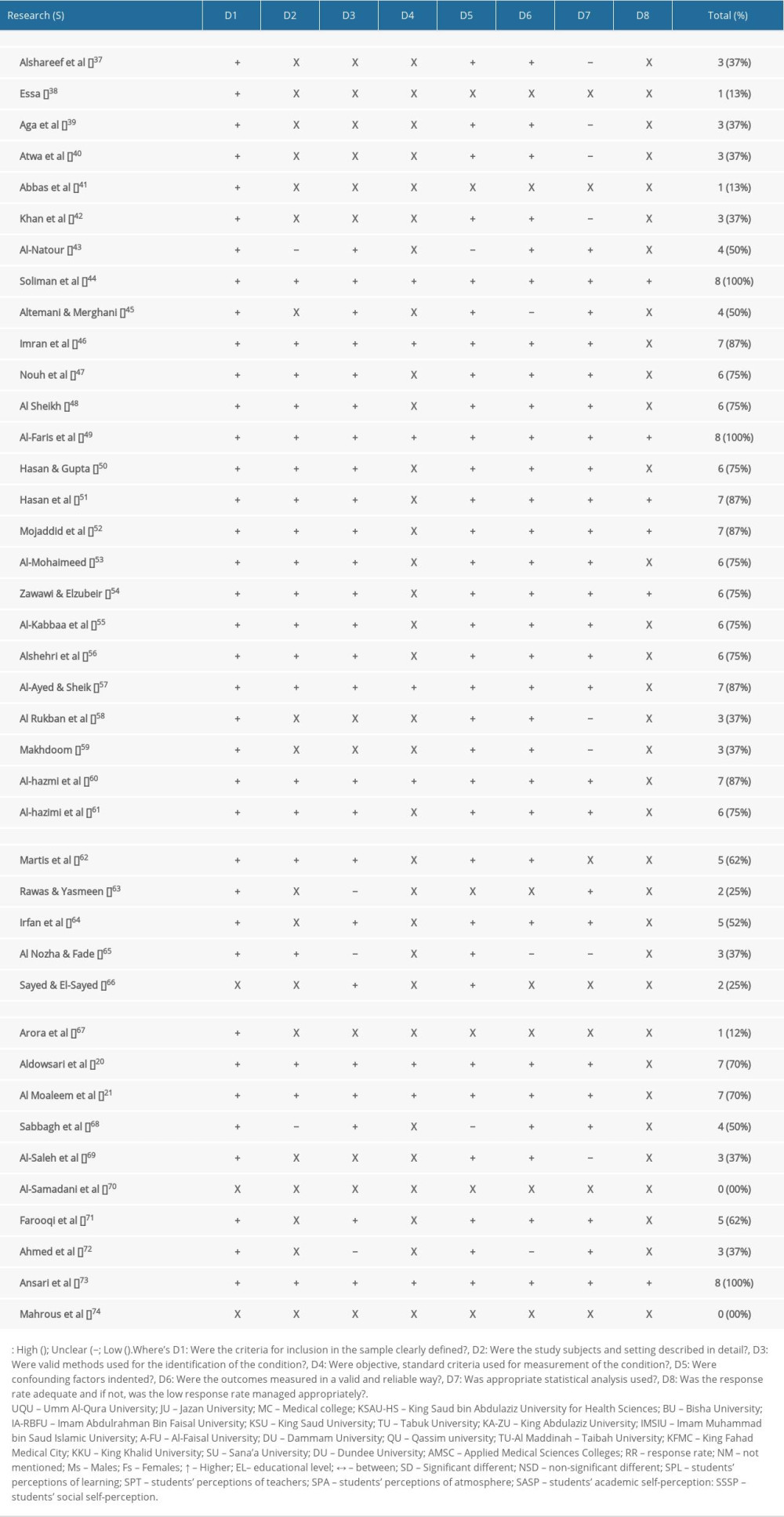

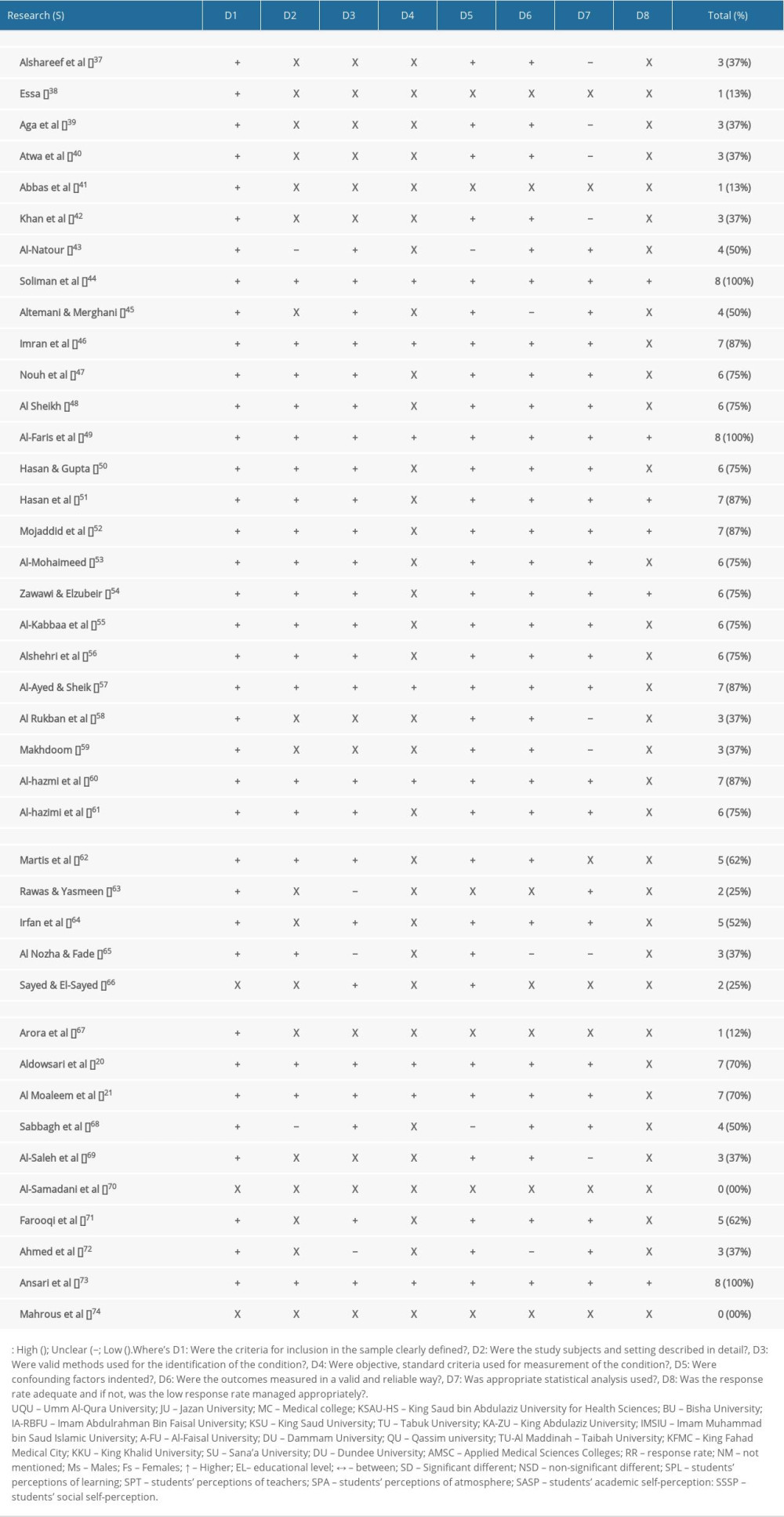

QUALITY OF SELECTED PAPERS:

The evaluation of the risk of bias revealed that more than half of the 40 articles had methodological limitations, resulting in an overall rating of medium to high risk of bias. Most of the papers used objective measures to determine DREEM and its 5 domains. In addition, some medical college studies did not mention the means and values of the 5 domains. The risk of bias assessment showed that all 40 included papers suffered from methodological weaknesses [35,36], leading to an overall high risk of bias. Most of the studies showed attrition bias with a lack of responses. There was limited information on how the response rate was managed. Table 3 contains the summary of the risk of bias.

STUDY CHARACTERISTICS:

A total of 25 medical colleges studies remained, including 7 in Riyadh, 5 in Jeddah, and 3 each in Dammam, Jazan, and Al Maddinah Al Manwareh [37–61]. Applied medical science colleges studies (5) were conducted in Abha, Jeddah, Riyadh, Al Maddinah Al Manwareh, and Makkah [62–66]. Lastly, in the 10 dental studies, 3 were performed in Al Maddinah Al Manwareh and 2 were conducted in Jazan [20–21,67–74]. Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the selected papers’ DREEM and its 5 domains conducted in different health specialties in SA.

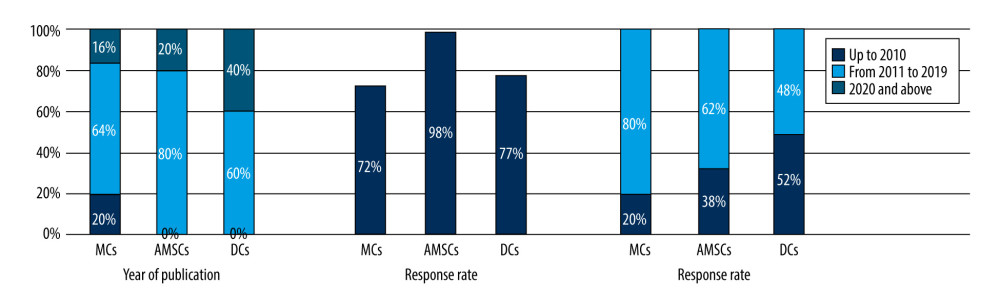

PUBLICATION YEARS, RR, AND GENDER RATIO: Most of the selected papers were published between 2011 and 2019 in all colleges (medical colleges, dental colleges, and applied medical science colleges). The percentages of the published articles in 2020 and later were 40%, 20%,16% for dental colleges, applied medical science colleges, and medical colleges, respectively. In relation to RR, the highest percentage was registered in applied medical science studies (98%), followed by dental (77%) and medical studies (72%). The male-to-female ratio in dental colleges participants was equal, whereas the ratio of females was higher in medical colleges and applied medical science colleges (80% and 62%, respectively) compared with males (20% and 38%, respectively) (Figure 2).

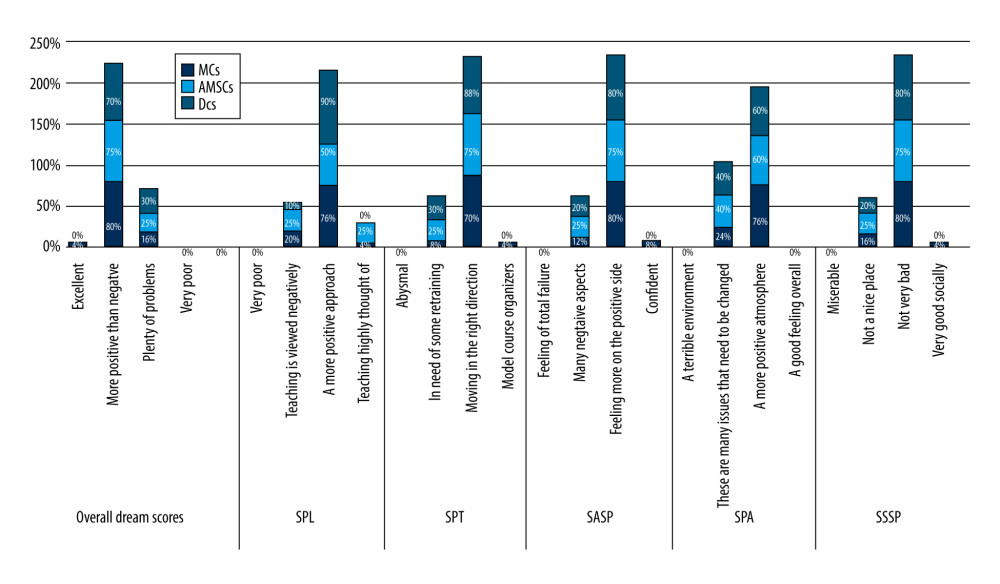

OVERALL DREEM AND SPL, SPT, SASP, SPA, AND SSSP DOMAIN VALUES: Table 4 and Figure 3 show the interpretations of the overall value of DREEM and its mean. The overall DREEM scores were 80%, 75%, and 70% for medical colleges, applied medical science colleges, and dental colleges, respectively, which indicates that most of them were “more positive than negative”, with values between 101 and 150. Meanwhile, a single study recorded as “Excellent,” with values between 151 and 200, and it was conducted in medical colleges in UQU in Makkah City.

Regarding the domains, for the educational environment of SPL, the values for dental colleges, medical colleges, and applied medical science colleges were 90%,76%, and 50%, respectively. These percentages imply that SPL is “a more positive approach, with values of 25–36 out of 48”. For SPT, the percentages were 88%, 75%, and 70% for medical colleges, applied medical science colleges, and dental colleges, which indicates that it is “moving in the right direction, with values of 23–33 out of 44”. In addition, a single study for SPT recorded 4%, which implied “model course organizer” and with values of 34–44. Regarding the SASP domain, the maximum values were almost equal for all colleges (75–80%), indicating that SASP is “feeling more on the positive side” in the educational environment. For SPA, the proportions were slightly higher in medical colleges (76%) compared with the 60% for applied medical science colleges and dental colleges, which indicated that the educational environment is “a more positive atmosphere”; for applied medical science colleges and dental colleges (40%), “there are many issues that need to be changed”, and their values were between 13 and 24 out of 48. Finally, SSSP values were almost equal and could be interpreted as “not very bad” with mean scores between 15 and 21 out of 28”. A single study for SSPP indicated “very good socially”, with mean values from 22 to 28. These interpretations were according to the values presented in Table 2.

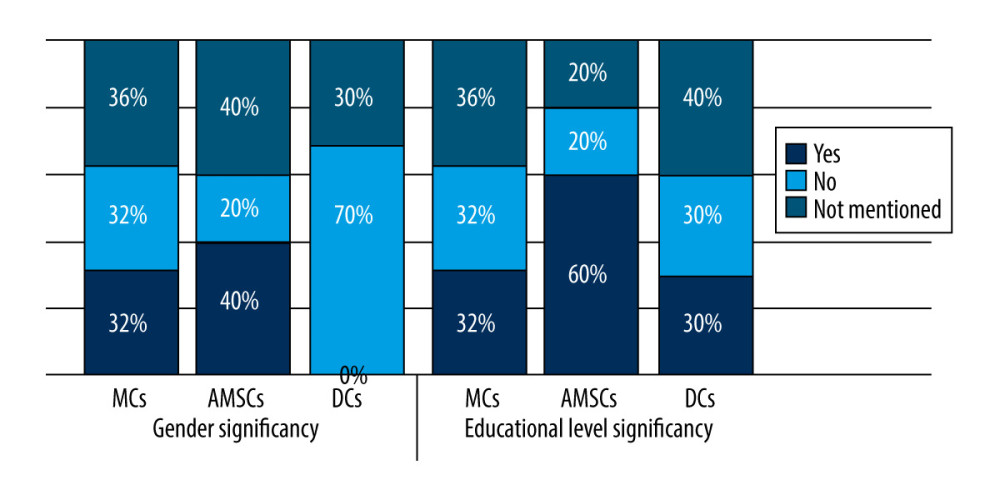

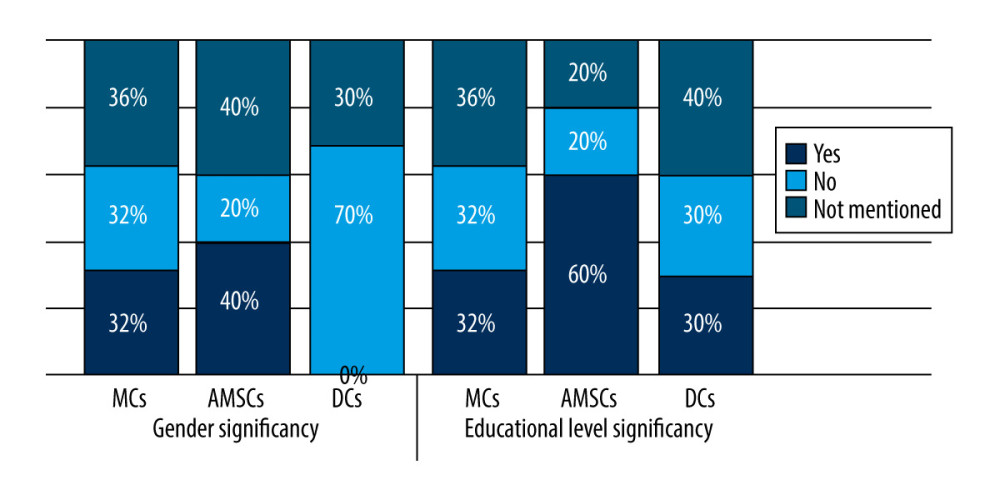

SIGNIFICANCE OF GENDER AND EDUCATIONAL LEVEL: Significant difference between genders was highest in applied medical science colleges (40%), followed by in medical colleges (32%), whereas most of dental colleges studies (70%) did not have any gender significance. In medical colleges and dental colleges, significant differences in educational levels were almost equal, accounting for 32% and 30% for “yes” and “no”, respectively. Significant differences were also observed in applied medical science colleges studies (60%; Figure 4).

Discussion

PUBLICATION YEARS, RR, AND GENDER RATIO:

After 2020, 40%, 20%, and 16% of publications were for dental colleges, applied medical science colleges, and medical colleges, respectively; these values were considerably lower compared with the percentage of articles published before 2020. Other systematic reviews by Behkam et al [24] and Farooqi et al [27] arrived at the same conclusions. Miles et al [15] used studies before 2010, and their review is in parallel with the percentage of studies in the current paper, as presented in Table 3 and Figure 2. RR was high in all colleges, particularly in applied medical science colleges (98%), which could be due to the limited number of students in each specialty. Females had higher percentages than males, which agrees with the results of Park et al [18] and Hernández-Crespo [17] in assessment of Korean and Spanish health college students, respectively. In a recent study conducted in Germany, Serrano et al [75] found that the percentage of women was higher than that of men. In other published articles [28,30] and in a single systematic review in SA [31], the same ratios were given.

OVERALL VALUE OF DREEM:

Males and females in SA go to separate buildings, with their own classrooms, offices, exam duties, and staff, as well as different patterns of teaching and educational environment. Thus, a significant difference exists between genders in most medical colleges, applied medical science colleges, and dental colleges. Regarding the overall value of DREEM for educational environment among gender, female students have a slightly higher mean DREEM score than male students. The overall DREEM score value in the medical, dental, and applied medical science colleges studies in this systematic review indicate that the students’ perceptions of educational environment in this colleges are “more positive than negative”. This result agrees with most studies conducted in different health specialties in different countries [17–18,27–28,30]. Recently, Serrano et al [75] assessed the educational environments in dental colleges in the Netherlands, and Behkam et al [24] investigated medical colleges at the Dundee University Medical School; both studies recorded slightly higher DREEM scores than the scores in the current review. Another study, performed by Hernández-Crespo et al [17] in Spain, indicated that the overall DREEM score of the educational environment among dental colleges students was “more positive than negative” in different academic years of 2010–2011, 2013–2014, 2014–2015, and 2015–2016. Slightly higher values, which were interpreted as “excellent,” were recorded among dental colleges students in Europe and China [27–28,30]. However, in this review, a single study conducted recently in medical colleges in UQU in Makkah City recognized a similar overall DREEM score. Another study [66] conducted among applied medical science colleges students recorded an overall DREEM score that was near excellent. However, the overall DREEM results in this review revealed that the mean score of the studies after 2019 was higher than that before 2019 in most of the included colleges. One reason for this could be that most of the recent studies were conducted in an intermediate educational environment; moreover, teaching and learning methods have changed, and technology has advanced. As a result of different reviews worldwide, the same range of overall DREEM was found [18,27,29]. A recent review by Alqahtani [31] found similar values in medical colleges and dental colleges in SA with different educational levels, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 4.

Zamzuri et al [76] were the first to analyze the EE for dental colleges in Malaysia, particularly for dental assistants and dental prosthesis students from a dental training institute, registering 125 and 118 out of 200, respectively. Furthermore, in a study involving 126 students from the Dentistry School of Manipal (India), Thomas et al [77] found an educational environment mean score of 115/200. A similar score was reported by Stratulat et al [78]. These values are similar to or lower than the values in the current review in dental colleges.

SPL, SPT, SASP, SPA, AND SSSP DOMAIN VALUES:

Figure 3 and Table 3 present the DREEM domains (SPL, SPT, SASP, SPA, and SSSP). SPL values were about the same as those in previous reviews in different countries [27,74,79], whereas SPT and SPA values were higher in the current review than in previous reviews conducted in Spain, SA, and Germany [17,26,31] and compared with other articles worldwide [27,76,78]. In terms of students’ perceptions of educational environments, medical colleges obtained significantly higher mean scores on domain items related to teaching strategies, teachers, and their social lives. Similar findings were obtained from Spain, the Netherlands, Australia, and Germany [17,27,75–79]. According to recently published literature, students’ perceptions for educational environment for SASP were equal in medical colleges, applied medical science colleges, and dental colleges [26,31,38,74,77]. SSSP values were almost equal among the 3 types of specialties and were interpreted as “not very bad”, with mean scores between 15 and 21 out of 28 [27,31,76,79]. A single study for SSPP indicated “very good socially”, with mean values from 22 to 28 (Table 2). These values have not been reported in any previous reviews, which could be because this is a newly established private college.

SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCES IN GENDER AND EDUCATIONAL LEVELS:

As shown in Figure 4 and Table 3, significant differences were recorded between genders among different health specialties, with the highest value in dental colleges studies. In studies conducted among different health specialties worldwide, comparable findings were obtained [17–18,26,30–31,75]. Some papers indicated that females recorded a higher level of DREEM compared with males [52,54,68] in medical colleges, whereas others claimed the opposite [55,65]. Few articles mentioned significant differences among colleges [46,54,64], universities [47,60], and specialties [62,64], and other studies indicated significant differences among parameters such as marital status and cumulative grades [69,73]. Among different educational levels or study phases (preclinical and clinical), significant differences were found among students from medical colleges [39,42,46,49,52,55,57], applied medical science colleges [63,65], and dental colleges [20,74]. Similar conclusions were achieved worldwide [17,24,31,39,75].

A limitation of the current review is that it did not include studies from colleges of pharmacy, and the number of applied medical science colleges was small. In addition, it did not include many studies from private colleges. Another limitation could be the lower percentage of articles in recent years.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from this systematic review. Overall, the DREEM scores were “more positive than negative” among all involved colleges, with scores between 101 and 150. In relation to the 5 domains of DREEM, medical colleges studies ranged from 75% to 88%, dental colleges studies had higher scores of 85% to 90%, and applied medical science colleges had lower scores of 50% to 75%. The gender percentage with significant value was considerably higher in dental colleges than in medical colleges and applied medical science colleges, whereas educational levels were higher in applied medical science colleges studies.

Figures

![Flowchart of the article selection process in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis [33–35].](https://jours.isi-science.com/imageXml.php?i=medscimonit-28-e938987-g001.jpg&idArt=938987&w=1000) Figure 1. Flowchart of the article selection process in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis [33–35].

Figure 1. Flowchart of the article selection process in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis [33–35].  Figure 2. Distribution of studies according to percentage of publication year, Response Rate, and gender (n=40).

Figure 2. Distribution of studies according to percentage of publication year, Response Rate, and gender (n=40).  Figure 3. Interpretations of overall mean of DREEM and its 5 domains among different colleges (n=40).

Figure 3. Interpretations of overall mean of DREEM and its 5 domains among different colleges (n=40).  Figure 4. Distribution of studies according to gender and educational levels percentage (n=40).

Figure 4. Distribution of studies according to gender and educational levels percentage (n=40). Tables

Table 1. Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure with its 50 items and 5 domains [5,7,12].![Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure with its 50 items and 5 domains [5,7,12].](https://jours.isi-science.com/imageXml.php?i=t1-medscimonit-28-e938987.jpg&idArt=938987&w=1000) Table 2. Interpretation guide of overall Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure and domain scores [5,7,12].

Table 2. Interpretation guide of overall Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure and domain scores [5,7,12].![Interpretation guide of overall Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure and domain scores [5,7,12].](https://jours.isi-science.com/imageXml.php?i=t2-medscimonit-28-e938987.jpg&idArt=938987&w=1000) Table 3. Risk of bias ratings based on Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools.

Table 3. Risk of bias ratings based on Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. Table 4. Total studies (n=40) conducted in Saudi Arabia that used Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure in Medical (n=25), Applied Medical Science (n=5), and Dental (n=10) colleges.

Table 4. Total studies (n=40) conducted in Saudi Arabia that used Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure in Medical (n=25), Applied Medical Science (n=5), and Dental (n=10) colleges.

References

1. Pavan A, Higher education in Saudi Arabia: Rooted in heritage and values. Aspiring to progress: Int Rese High Educ, 2016; 1(1); 91-100

2. Bajammal S, Zaini R, Abuznadah W, The need for the national medical licensing examination in Saudi Arabia: BMC Med Educ, 2008; 8; 53

3. Telmesani A, Zaini RG, Ghazi HO, Medical education in Saudi Arabia: A review of recent developments and future challenges: East Medit Health J, 2011; 17(8); 702-7

4. Alamri M, Higher education in Saudi Arabia: J High Educ Theory Practice, 2011; 11(4); 88-91

5. Roff S, McAleer S, What is educational climate?: Med Teacher, 2001; 23(4); 333-43

6. Sutliff M, Higginson J, Allstot S, Building a positive learning environment for students: Advice to beginning teachers: Strategies, 2008; 22(1); 31-33

7. Roff S, Mcaleer S, Harden RM, Al-qahtani M, Development and validation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM): Med Teacher, 1997; 19; 295-99

8. Hanrahan M, The effect of learning environment factors on students’ motivation and learning: Int J Scie Educ, 1998; 20(6); 737-53

9. Harden RM, The learning environment and the curriculum: Med Teacher, 2001; 23(4); 335-48

10. Chan DSK, Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in assessing hospital learning environments: Int J Nursing Stud, 2001; 38; 447-59

11. Moore-west M, Harrington DL, Mennin SP, Distress and attitudes toward the learning environment: Effects of a curriculum innovation: Teach Learn Med, 1989; 1; 151-57

12. Roff S, The Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) – a generic instrument for measuring students’ perceptions of undergraduate health professions curricula: Med Teacher, 2005; 27; 322-25

13. The World Federation for Medical Education (WFME), Executive Council: International standards in medical education: assessment and accreditation of medical schools’ – educational programmes. A WFME position paper: Med Educ, 1998; 32(5); 549-58

14. Genn JM, Curriculum, environment, climate quality and change in medical education – a unifying perspective: Medical Teacher, 2001; 23(5); 445-54

15. Miles S, Swift L, Leinster SJ, The Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM): A review of its adoption and use: Med Teacher, 2012; 34(9); e620-34

16. Alraawi MA, Baris S, Al Ahmari NM, Analyzing students’ perceptions of educational environment in new dental colleges, Turkey using DREEM inventory: Biosc Biotech Res Comm, 2020; 13(2); 556-64

17. Hernández-Crespo AM, Fernández-Riveiro P, Rapado-González O, Students’ perceptions of educational climate in a spanish school of dentistry using the dundee ready education environment measure: A longitudinal study: Dent J, 2020; 8; 133

18. Park KH, Park JH, Kim S, Students’ perception of the educational environment of medical schools in Korea: Findings from a nationwide survey: Korean J Med Educ, 2015; 27(2); 117-30

19. Altawaty A, Othman EMT, Alkuwafi RM, El-kilani S, Comparison of Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure with an abridged version at a dental school: MedEdPublish, 2020; 9; 234

20. Aldowsari MK, Al-Ahmari MM, Aldosari LI, Comparisons between preclinical and clinical dental students’ perceptions of the educational climate at the college of dentistry, Jazan University: Adva Med Educ Practice, 2021; 12; 11-28

21. Al Moaleem MM, Shubayr MA, Aldowsari MK, Gender comparison of students’ perception of educational environment using DREEM inventory, College of Dentistry, Jazan University: Open Dent J, 2020; 14; 641-49

22. Bassaw B, Roff S, McAleer S, Students’ perspectives on the educational environment, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Trinidad: Med Teach, 2003; 25(5); 522-526

23. Rahman NIA, Aziz AA, Zulkifli Z, Perceptions of students in different phases of medical education of the educational environment: Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin: Adv Med Educ Pract, 2015; 6; 211-22

24. Behkam S, Tavallaei A, Maghbouli N, Students’ perception of educational environment based on Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure and the role of peer mentoring: A cross-sectional study: BMC Med Educ, 2022; 22; 176

25. Eslami N, Farzin S, Mojarad AN, perception of students on the educational environment of Mashhad dental school based on the DREEM questionnaire during 2020–2021: Iran J Orthod, 2022; 17(1); e1064

26. Yeturu SK, Kumar VS, Pentapati KC, Students’ perceptions of their educational environment in a south Indian dental school – A cross-sectional study: J Int Oral Health, 2022; 14; 518-23

27. Farooqi FA, Khan SQ, Khabeer A, Ali S, Al-Ansari A, Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure tool for evaluating the educational environment: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Maced J Med Sci, 2020; 8(F); 108-16

28. Soemantri D, Herrera C, Riquelme A, Measuring the educational environment in health professions studies: A systematic review: Med Teacher, 2010; 32; 947-52

29. Leman MA, Construct validity sssessment of Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measurement (DREEM) in a school of dentistry: Indonesian J Med Educ, 2017; 6(1); 11-19

30. Chan CYW, Sum MY, Tan GMY, Tor P-C, Sim K, Adoption and correlates of the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) in the evaluation of undergraduate learning environments – a systematic review: Med Teacher, 2018; 40(12); 1240-47

31. Alqahtani SM, Comparison Of DREEM, domines, and item scores between dental and medical colleges in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review: J Positive School Psychology, 2022; 6(6); 4389-405

32. Salameh JP, Bossuyt PM, McGrath TA, Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies (PRISMA-DTA): Explanation, elaboration, and checklist: BMJ, 2020; 370; m2632

33. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies: J Clin Epidemiology, 2008; 61(4); 344-49

34. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Joanna Briggs Institute: Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies, 2017 https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Analytical_Cross_Sectional_Studies2017_0.pdf

35. Mangory KY, Ali LY, Rø KI, Tyssen R, Effect of burnout among physicians on observed adverse patient outcomes: A literature review: BMC Health Serv Res, 2021; 21(1); 369

36. Tarrosh MY, Alhazmi YA, Aljabri MY, A systematic review of cross-sectional studies conducted in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on levels of dental anxiety between genders and demographic groups: Med Sci Monit, 2022; 28; e937470

37. Alshareef M, Khouj G, Alqahtani S, Perception of the learning environment among medical students at Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia: Majmaah J Health Sci, 2022; 10(3); 88-100

38. Essa M, Students perceptions of learning environment in Jazan Medical School in Saudi Arabia: Research Square, 2022; 1-35

39. Aga SS, Khan MA, Al Qurashi M, Khawaji B, Medical students’ perception of the educational environment at college of medicine: A prospective study with a review of literature: Educ Rese Inter, 2021; 7260507

40. Atwa H, Alkhadragy R, Abdelaziz A, Medical students’ perception of the educational environment in a gender-segregated undergraduate program: J Med Edu, 2020; 19(3); e104934

41. Abbas M, Salih K, Elhassan KEH, Measurement of the educational environment of an innovative, undergraduate medical program in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia using DREEM: International Journal of Medicine Developing Countries, 2020; 4(11); 1734-37

42. Khan S Q, Al-Shahrani M, Khabeer A, Medical students’ perception of their educational environment at Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: J Fam Community Med, 2019; 26; 45-50

43. Al Natour SH, Medical students’ perceptions of their educational environment at a Saudi University: Saudi J Med Med Sci, 2019; 7; 163-68

44. Soliman MM, Sattar K, Alnassar S, Medical students’ perception of the learning environment at King Saud University Medical College, Saudi Arabia, using DREEM Inventory: Adv Med Educ Pract, 2017; 8; 221-27

45. Altemani HA, Merghani TH, The quality of the educational environment in a medical college in Saudi Arabia: Inte J Med Educ, 2017; 8; 128-32

46. Imran N, Khalid F, Haider II, Student’s perceptions of educational environment across multiple undergraduate medical institutions in Pakistan using DREEM inventory: J Pak Med Assoc, 2015; 65; 24-28

47. Nouh T, Anil S, Alanazi A, Assessing correlation between students’ perception of the learning environment and their academic performance: J Pak Med Assoc, 2016; 66(12); 1616-20

48. Al Sheikh MH, Educational environment measurement, how is it affected by educational strategy in a Saudi medical school? A multivariate analysis: J Taibah Univ Med Sci, 2014; 9; 115-22

49. AlFaris AE, Naeem N, Irfan F, Student centered curricular elements are associated with a healthier educational environment and lower depressive symptoms in medical students: BMC Med Educ, 2014; 14(1); 192-202

50. Hasan T, Gupta T, Assessing the learning environment at Jazan Medical School of Saudi Arabia: Med Teacher, 2013; 35

51. Hasan T, Gupta P, Female student DREEMS at Jazan Medical School of Saudi Arabia: Med Teacher, 2013; 35(2); 172-73

52. Mojaddidi MA, Khoshhal KI, Habib F, Reassessment of the undergraduate educational environment in College of Medicine, Taibah University, Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia: Med Teacher, 2013; 35(Suppl 1); S39-46

53. Al Mohaimeed A, Perceptions of the educational environment of a new medical school, Saudi Arabia: Int J Health Sci (Qassim), 2013; 7; 150-59

54. Zawawi AH, Elzubeir M, Using DREEM to compare graduating students’ perceptions of learning environments at medical schools adopting contrasting educational strategies: Med Teacher, 2012; 34(Suppl 1); S25-31

55. Al-Kabbaa A, Ahmad H, Saeed A, Perception of the learning environment by students in a new medical school in Saudi Arabia: Areas of concern: J Taib Uni Med Sci, 2012; 7; 69-75

56. Alshehri SA, Alshehri AF, Erwin TD, Measuring the medical school educational environment: Validating an approach from Saudi Arabia: Health Educ J, 2012; 71(5); 553-64

57. Al Ayed IH, Sheik SA, Assessment of the educational environment at the college of medicine of King Saud university, Riyadh: East Mediterr Health J, 2011; 14; 953-59

58. Al Rukban MO, Khalil MS, Al-Zalabani A, Learning environment in medical schools adopting different educational strategies: Educ Rese Reviews, 2010; 5(3); 126-29

59. Makhdoom N M, Assessment of the quality of educational climate during undergraduate clinical teaching years in the College of Medicine, Taibah University: J Taib University Med Scie, 2009; 4(1); 42-52

60. Al-Hazimi A, Al-Hyiani A, Roff S, Perceptions of the educational environment of the medical school in King Abdul Aziz University, Saudi Arabia: Med Teacher, 2004; 26(6); 570-73

61. Al-Hazimi A, Zaini R, Al-Hyiani A, Educational environment in traditional and innovative medical Page 24/25 schools: A study in four undergraduate medical schools: Educ for Health, 2004; 17(2); 192-203

62. Martis M, Abdullah H, Oommen A, Perceived education environment of the undergraduate health profession programs in Saudi Arabia: Saudi J Nurs Health Care, 2021; 4(12); 472-81

63. Rawas H, Yasmeen N, Perception of nursing students about their educational environment in College of Nursing at King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Saudi Arabia: Med Teach, 2019; 41(11); 1307-14

64. Irfan F, Al-Faris E, Al-Maflehi N, The learning environment of four undergraduate health professional schools: Lessons learned: Pak J Med Sci, 2019; 35(3); 598-604

65. Al Nozha OM, Fadelb HT, Student perception of the educational environment in regular and bridging nursing programs in Saudi Arabia using the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure: Ann Saudi Med, 2017; 37(3); 225-31

66. Sayed HY, El-Sayed NG, Students’ perceptions of the educational environment of the nursing program in Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences at Umm Al Qura University, KSA: Journal of American Science, 2012; 8(4); 69-75

67. Arora G, Nawabi S, Uppal M, Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure of dentistry: Analysis of dental students’ perception about educational environment in College of Dentistry, Mustaqbal University: J Pharm Bioall Sci, 2021; 13; S1544-50

68. Sabbagh HJ, Bakhaider HA, Abokhashabah HM, Bader MU, Students’ perceptions of the educational environment at King Abdulaziz University Faculty of Dentistry (KAUFD): A cross sectional study: BMC Med Educ, 2020; 20; 241

69. Al-Saleh S, Al-Madi EM, AlMufleh B, Al-Degheishem A, Educational environment as perceived by dental students at King Saud University: Saudi Dent J, 2018; 30; 240-49

70. Al-Samadani KH, Ahmad MS, Bhayat A, Comparing male and female dental students’ perceptions regarding their learning environment at a dental college in Northwest, Saudi Arabia: Eur J Gen Dent, 2016; 5; 80-85

71. Farooqi FA, Moheet IA, Khan SQ, First year dental students’ perceptions about educational environment: Expected verses actual perceptions: Inte J Deve Resea, 2015; 5(6); 4735-40

72. Ahmad MS, Bhayat A, Fadel HD, Comparing dental students’ perceptions of their educational environment in Northwestern Saudi Arabia: Saudi Med J, 2015; 36(4); 477-83

73. Al-Ansari MA, Tantawi M, Predicting academic performance of dental students using perception of educational environment: J Dent Educ, 2015; 79; 30

74. Mahrous M, Al Shorman H, Ahmad MS, Assessment of the educational environment in a newly established dental college: J Educ Ethics Dent, 2013; 3; 6-13

75. Serrano CM, Lagerweij MD, de Boer IR, Students’ learning environment perception and the transition to clinical training in dentistry: Eur J Dent Educ, 2021; 25(4); 829-36

76. Zamzuri AT, Azli NA, Ro S, McAleer S, How do students at dental training college Malaysia perceived their educational environment? Malays: Dent J, 2004; 25; 15-26

77. Thomas BS, Abraham RR, Alexander M, Ramnarayan K, Students’ perceptions regarding educational environment in an Indian Dental School: Med Teach, 2009; 31; e185-86

78. Stratulat SI, Candel OS, Tabîr A, The perception of the educational environment in multinational students from a dental medicine faculty in Romania: Eur J Dent Educ, 2019; 24; 193-98

79. Ostapczuk M, Hugger A, De Bruin J, DREEM on, dentists! Students’ perceptions of the educational environment in a German dental school as measured by the Dundee ready education environment measure: Eur J Dent Educ, 2012; 16(2); 67-77

Figures

Figure 1. Flowchart of the article selection process in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis [33–35].

Figure 1. Flowchart of the article selection process in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis [33–35]. Figure 2. Distribution of studies according to percentage of publication year, Response Rate, and gender (n=40).

Figure 2. Distribution of studies according to percentage of publication year, Response Rate, and gender (n=40). Figure 3. Interpretations of overall mean of DREEM and its 5 domains among different colleges (n=40).

Figure 3. Interpretations of overall mean of DREEM and its 5 domains among different colleges (n=40). Figure 4. Distribution of studies according to gender and educational levels percentage (n=40).

Figure 4. Distribution of studies according to gender and educational levels percentage (n=40). Tables

Table 1. Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure with its 50 items and 5 domains [5,7,12].

Table 1. Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure with its 50 items and 5 domains [5,7,12]. Table 2. Interpretation guide of overall Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure and domain scores [5,7,12].

Table 2. Interpretation guide of overall Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure and domain scores [5,7,12]. Table 3. Risk of bias ratings based on Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools.

Table 3. Risk of bias ratings based on Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. Table 4. Total studies (n=40) conducted in Saudi Arabia that used Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure in Medical (n=25), Applied Medical Science (n=5), and Dental (n=10) colleges.

Table 4. Total studies (n=40) conducted in Saudi Arabia that used Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure in Medical (n=25), Applied Medical Science (n=5), and Dental (n=10) colleges. Table 1. Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure with its 50 items and 5 domains [5,7,12].

Table 1. Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure with its 50 items and 5 domains [5,7,12]. Table 2. Interpretation guide of overall Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure and domain scores [5,7,12].

Table 2. Interpretation guide of overall Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure and domain scores [5,7,12]. Table 3. Risk of bias ratings based on Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools.

Table 3. Risk of bias ratings based on Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. Table 4. Total studies (n=40) conducted in Saudi Arabia that used Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure in Medical (n=25), Applied Medical Science (n=5), and Dental (n=10) colleges.

Table 4. Total studies (n=40) conducted in Saudi Arabia that used Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure in Medical (n=25), Applied Medical Science (n=5), and Dental (n=10) colleges. In Press

15 Apr 2024 : Laboratory Research

The Role of Copper-Induced M2 Macrophage Polarization in Protecting Cartilage Matrix in OsteoarthritisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943738

07 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 179 Male Third- and Fourt...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943468

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952