03 July 2023: Clinical Research

A Novel Method for Treating Distal Radius Diaphyseal Metaphyseal Junction Fracture in Children

Rufa Wang1EF, Dan Chen1BDE, Yuping Tang1EF, Minjie Fan1D, Yiwei Wang1D, Hanjie Zhuang1B, Ruoyi Guo1B, Pengfei Zheng1A*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.939852

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e939852

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The treatment of distal radius diaphyseal metaphyseal junction (DMJ) fracture in children is a clinical problem; several treatments are available, but none are very effective. Therefore, this study aimed to report a novel method for treating this fracture using limited open reduction and transepiphyseal intramedullary fixation with Kirschner wire.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: From January 2018 to December 2019, a total of 15 children (13 boys and 2 girls) with distal radius DMJ fractures with a mean age of 10 years (range: 6-14 years) were included in the study. The operation time, incision length, and X-ray radiation exposure were precisely recorded. All children were followed up regularly. At the final follow-up, clinical outcomes were evaluated according to Price criteria, and complications were recorded.

RESULTS: The mean operation time of the 15 children was 21.4 min, and the mean incision length was 1.9 cm. The intraoperative X-ray was performed 3.7 times on average. The mean radiographic union of fracture was 4.7 weeks, and the mean time to remove the Kirschner wire was 4.8 weeks for radial instrumentation and 4.7 months for ulnar instrumentation. According to the Price grading evaluation system, clinical outcome was excellent in 14 cases and good in 1 case. Moreover, there were no major complications related to loss of reduction, malunion, nonunion, and physeal arrest of the distal radius.

CONCLUSIONS: Limited open reduction and transepiphyseal intramedullary fixation with Kirschner wire are effective for treating distal radius DMJ fracture in children, which has the advantages of simple surgical procedures, short operation time, small incision, and less radiation exposure, making it an excellent choice for treating this fracture.

Keywords: Fracture Fixation, Intramedullary, Pediatrics, Radius Fractures, Male, Female, Humans, Child, Radius, Treatment Outcome, Bone Wires, Fracture Fixation, Internal, Wrist Fractures

Background

Distal radius fractures are the most common fracture in children [1–4]. Manual reduction plaster fixation has always been the first treatment choice, given its characteristics of rapid fracture union and strong plastic ability in children [5]. In 2010, Lieber et al first proposed the concept of diametaphyseal transition (DMT) fracture in children [2]. Later, other researchers redefined it as diaphyseal metaphyseal junction (DMJ) fracture [6–8]. Compared with most distal radius fractures, this kind of fracture has a low success rate of manual reduction. Moreover, it is easy to displace after successful reduction, owing to the small contact area between 2 ends of the fracture, which makes treatment very challenging. Currently, the primary clinical treatment of this fracture is an open reduction with plate screw fixation [3,5,9] or elastic intramedullary nail fixation [2,3,6–8,10]. In addition, Kirschner wire fixation [2–5] or external fixator fixation [3,11] are also common options. However, these methods hardly meet the requirements of being minimally invasive, rapid, simple, and economical while ensuring good therapeutic results. In this study, we reported a novel method to treat DMJ fractures in children, which we referred to as limited open reduction and transepiphyseal intramedullary fixation with Kirschner wire, and evaluated its therapeutic effect.

Material and Methods

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from the parents/guardians of the patients. Consent to publish was obtained from the patients’ guardians to publish the identifying images in the manuscript file. The AO Pediatric Long Bone Fracture Consolidated Classification [12] defines metaphysis as a square-shaped area that contains the most comprehensive portion of the double growth plate on the posteroanterior radiographs, while the diaphysis is the part between the 2 epiphyses of long bones. However, the diaphyseal metaphyseal junctional (DMJ) region remained undefined. To address this issue, Lieber et al first introduced the concept of distal radius diametaphyseal transition (DMT) in children, which refers to the square area containing the widest part of the distal ulnar and radial growth plate, excluding the broadest part of distal radius growth plate on the posteroanterior radiographs [2]. Subsequently, other scholars redefined it as DMJ fracture [6–8]. In this study, we used the definition of DMJ to select the eligible patients.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the patient had a definite diagnosis of distal radius DMJ fracture and was older than 6 years of age; (2) the fracture end was completely displaced or angulated by more than 20°; (3) closed reduction failed or stable reduction could not be maintained. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pathological fracture; (2) DMJ combined with other fractures, except that of the distal ulna; (3) insufficient follow-up data and follow-up time less than 12 months.

From January 2018 to December 2019, a total of 15 children (13 boys and 2 girls) with distal radius DMJ fractures with a mean age of 10 years (range: 6–14 years) were included in the study. The mechanism of injury was diverse, and falls during exercise being the predominant cause. Eight patients were younger than 10 years and 7 patients were older than 10 years. Seven and 8 patients had left- and right-sided fractures, respectively. There were 3 patients with simple radius fractures, and 12 patients also had distal ulna fractures. Eight patients were fixed with ulnar elastic intramedullary nail fixation, and 4 patients were left untreated. The same surgeon treated all children with limited open reduction and transepiphyseal intramedullary fixation with Kirschner wire.

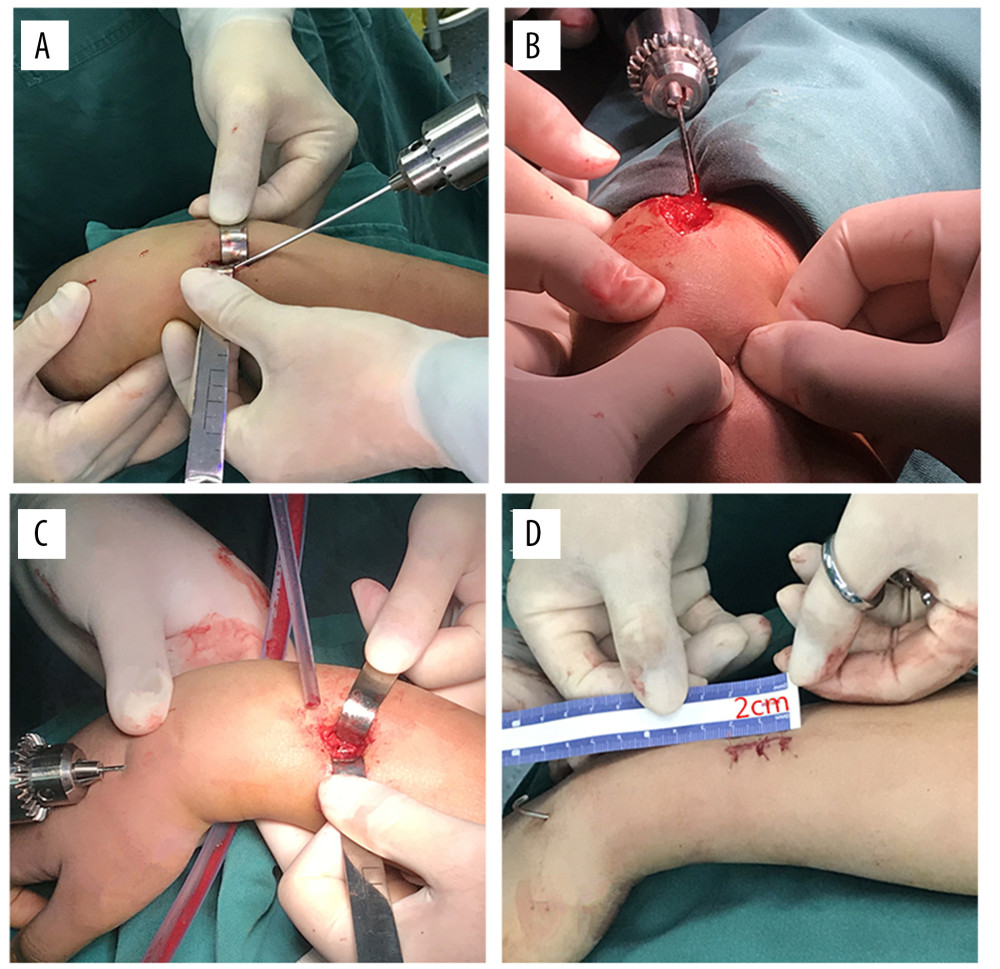

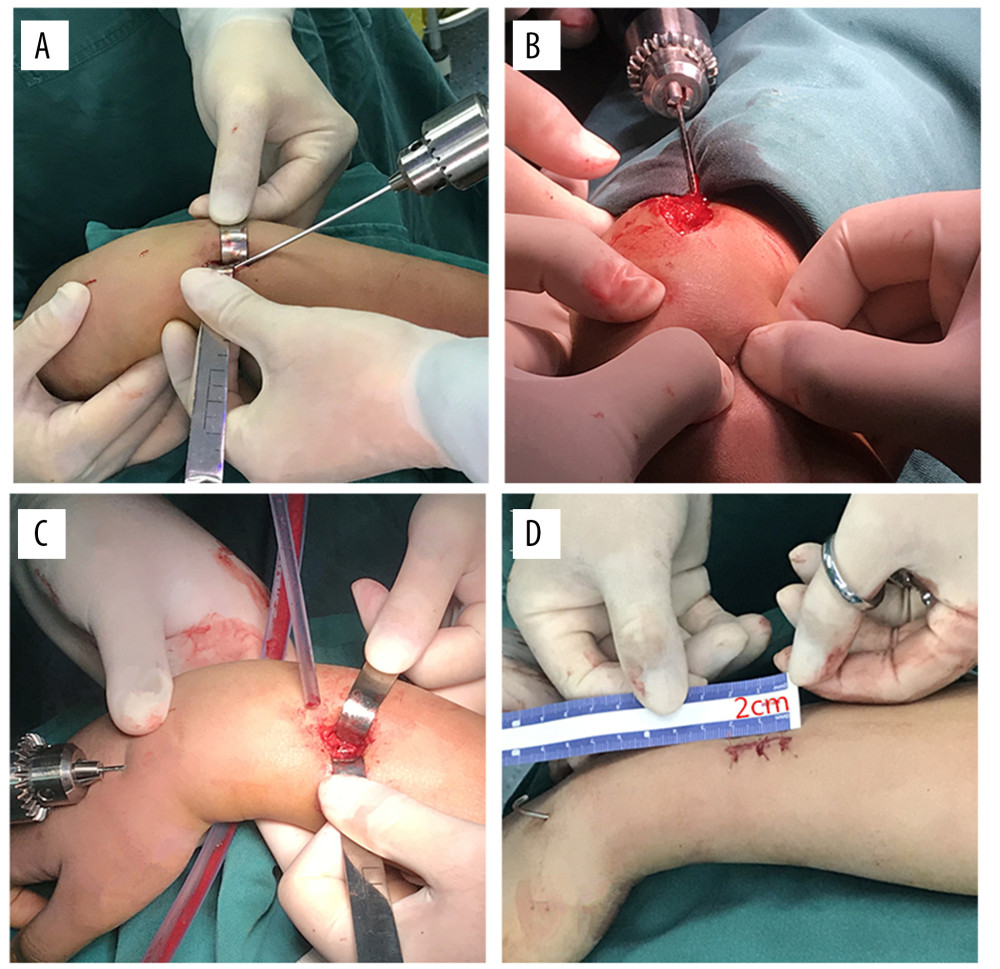

With the patient in the supine position, the affected limb was placed on the fluoroscopic table, and the operation began after routine disinfection. For children with distal ulnar fractures, no treatment or antegrade elastic intramedullary nail fixation was selected according to the severity of fracture displacement. Reduction and fixation of radial DMJ fracture was performed by taking the fracture site as the center, and a long dorsal longitudinal incision was made to expose the end of the fracture (Figure 1A). Then, a smooth Kirschner wire was inserted antegradely from the end of the fracture into the medullary cavity of the distal radius. The appropriate diameter of the Kirschner wire was selected according to the thickness of the medullary cavity. Generally, Kirschner wire with a diameter of 1.5 mm was chosen for patients <10 years, and that with a diameter of 2.0 mm was used for patients >10 years. The Kirschner wire was inserted perpendicular to the radial growth plate as far as possible, and into the wrist joint. To prevent damage to other wrist joint bones, the maximum palmar flexion of the wrist was maintained during insertion of the wire, allowing it to safely penetrate the skin. According to the exit position of the Kirschner wire, the assistant used 2 thumbs to touch and push the tendons on both sides to avoid the Kirschner wire penetrating the tendon (Figure 1B). The Kirschner wire passed out of the skin, and its proximal end was then retracted to the fracture site. Under direct vision, the reduction was performed to restore radial length, with particular attention to correcting the rotational deformity. After confirming successful reduction, the Kirschner wires were retrogradely inserted into the proximal radial medullary cavity (Figure 1C). The incision length was about 2 cm (Figure 1D). Preoperative and intraoperative C-arm fluoroscopy was performed to confirm successful fracture reduction and proper position of internal fixation (Figure 2A–2D). The wire was bent 90° at the end, and the skin at the needle discharge point was untangled properly using fingers to minimize skin irritation symptoms. Finally, the incision was closed and dorsal forearm plaster external fixation was performed.

The operation time, incision length, and X-ray radiation exposure were recorded, and only the surgical operation part of the radius fracture was recorded. Plaster external fixation was performed postoperatively, and all children were followed up regularly. After fracture union was confirmed by radiographs, the plaster and Kirschner wire were removed for radial internal fixation. After the removal of plaster, rehabilitation exercises were strengthened, including forearm rotation, palm flexion and extension, and muscle strength. Follow-up was at least 12 months. At the final follow-up, the grading evaluation system proposed by Price et al was used [13]. The result was considered excellent if there were no problems performing strenuous physical activity and/or <10° loss of forearm rotation. The result was considered good if there were only mild complaints with strenuous physical activity and/or an 11–30° loss of forearm rotation. The results were considered fair if mild subjective problems remained during daily activities and/or a 31–90° loss of forearm rotation was noted. The other results were considered poor. We compared the movement function of the operated side with that of the healthy side of the wrist. The occurrence of complications was recorded, and the main complications included loss of reduction, malunions, nonunion, and physeal arrest of the distal radius [14]. Minor complications included skin irritation over the Kirschner wire tail and slippage of the Kirschner wire tail.

Results

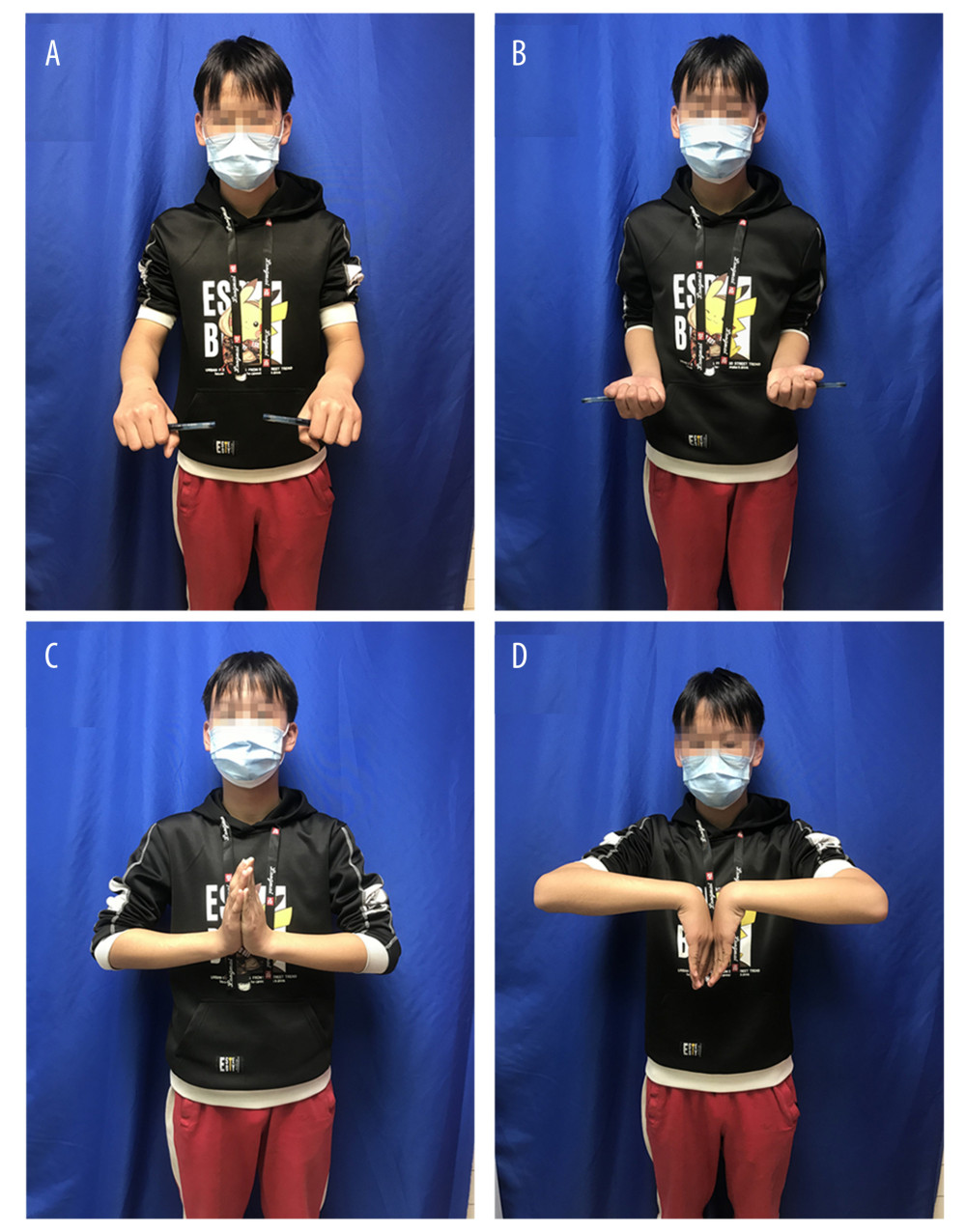

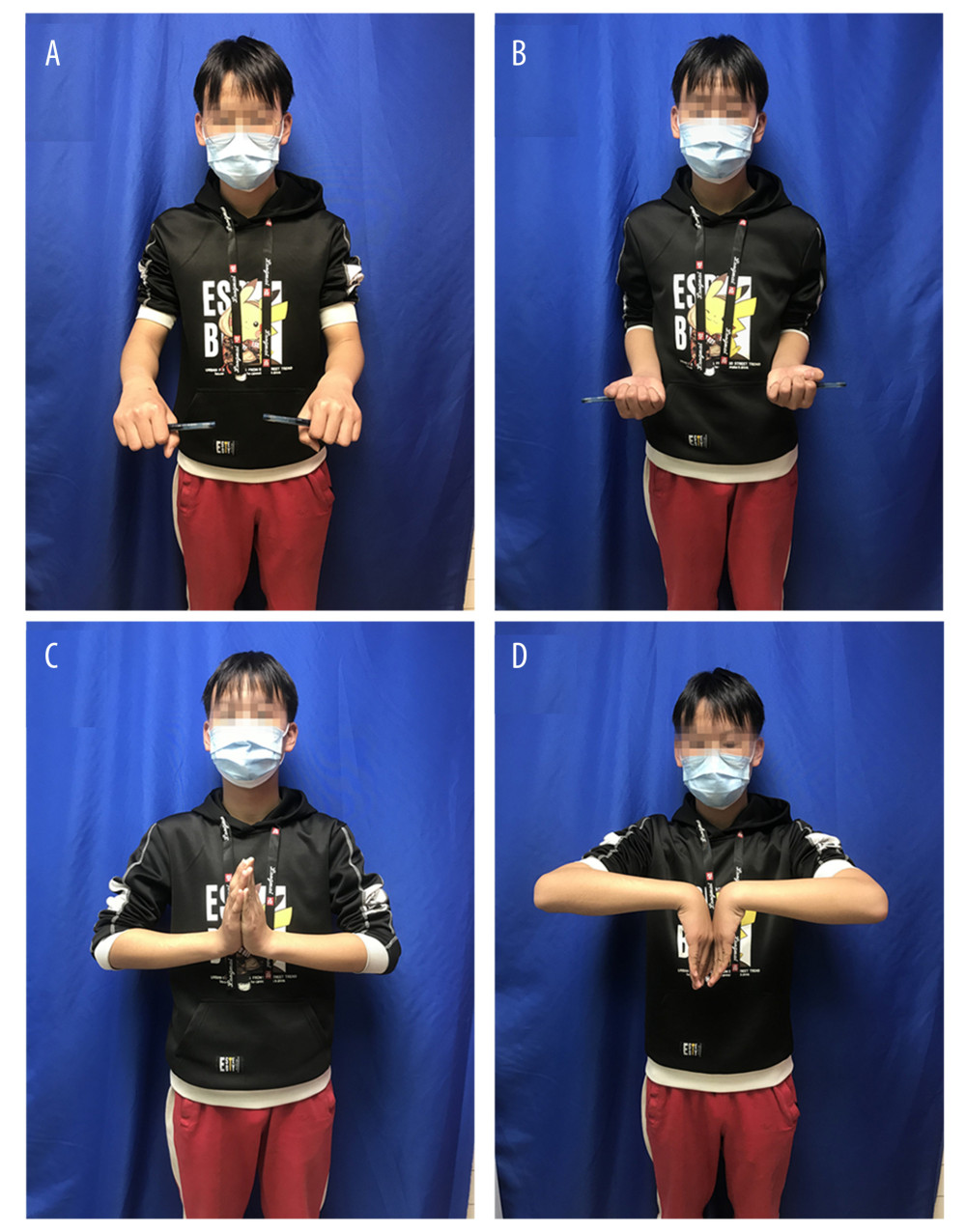

The mean operation time of the 15 children was 21.4 min (15–28 min), and the mean incision length was 1.9 cm (1.5–2.5 cm). On average, the intraoperative X-ray was performed 3.7 times (3–5 times). The average radiographic union of fracture was 4.7 weeks (4–6 weeks). The mean time to removal of the Kirchner wire was 4.8 weeks (4–6 weeks) for radial instrumentation (Figure 3A–3D) and 4.7 months (range, 3.0–5.5 months) for ulnar instrumentation. At the final follow-up, conducted 12 months after the surgery, the Price CT grading evaluation system was used to assess the outcomes. Out of the 15 patients, 14 had excellent results while 1 had a good result. Wrist movement function was not different from that of the healthy side (Figure 4A–4D). There were no instrumentation failures or re-operations. There were no significant complications related to loss of reduction, malunion, nonunion, and physeal arrest of the distal radius. One of them had a Kirschner wire tail trapped in the skin.

Discussion

The diameter of the distal radius DMJ fracture end and the contact area is relatively smaller than the metaphyseal fracture of the distal radius, and hence, it is unstable after reduction. This site has poorer plastic ability than the metaphysis, especially in older children [4]. Therefore, manual reduction can be tried for distal radius DMJ fracture, and open reduction and internal fixation are more suited for treatment if reduction fails or in case of unstable redisplacement after reduction. Hoël et al reported a reduction technique using the Kirchner wire as a “joy stick” [15], but we believe that this technique has the risk of damaging the peripheral vessels, tendons and nerves, and restoring the soft tissue embedded in the fracture site is difficult. This study introduces a new method for treating distal radius DMJ fractures in children. Only a small incision is needed to expose the fracture end to complete the anatomical reduction, and stable fixation can be completed using a Kirschner wire. The removal of the Kirschner wire in the second operation can be completed at the clinic under local anesthesia. Compared with various current surgical methods, this method has the advantages of simple surgical procedures, short time, small incision, and less radiation exposure.

Kirschner wire cross internal fixation is a safe and effective method for distal radius metaphyseal fractures [1–5], while elastic intramedullary nailing is currently the preferred choice for radial shaft fractures in children [2,3,16,17]. For distal radius DMJ fractures in children, both techniques have certain limitations. Kirschner wires cross the fracture line retrogradely through the distal epiphysis. When fixed in the proximal bone cortex of the fracture, Kirschner wire needs to be placed in a direction almost parallel to the bone shaft, which is technically challenging and needs to be repeatedly tried and confirmed by radiography, increasing the risk of radiation exposure and affecting the stability of the final fixation. However, if Kirschner wires are placed antegrade, it is difficult to determine the wire withdrawal point and hence easy to damage the distal nerves, blood vessels, tendons, and other soft tissues. Lieber et al proposed distal radius DMT fractures and treated 10 cases with transepiphyseal percutaneous Kirschner wire retrograde intramedullary fixation, with satisfactory results [5]. Kose et al compared intramedullary Kirschner wire versus screw with plate fixation for unstable forearm fractures in 32 children [5], including 5 cases of distal fracture, and concluded that transepiphyseal percutaneous Kirschner wire retrograde intramedullary fixation technique has the advantages of aesthetics, short operation time, easy removal, and low cost. Kubiak et al treated 5 patients using the above technique and obtained satisfactory results, proposing that the effect of at least 1 Kirschner wire in the medulla was better than that of an elastic intramedullary nail [4]. This is consistent with the conclusions of Choi [16], Yung [17], Lee [18], and other scholars on whether transepiphyseal Kirschner wires cause epiphyseal injury. Further, there are no reports of growth imbalance caused by epiphyseal injury. When trying this method, we found that it is not easy for a retrograde Kirschner wire to enter the medullary cavity across the epiphysis from the distal end. Kirschner wires often slip into the dorsal side of the distal end of the fracture, just as our method ends up requiring extreme flexion of the wrist; otherwise, it is difficult to enter the medullary cavity. When the direction of Kirschner wire insertion is adjusted to the metacarpal side, the bone cortex is often penetrated at the distal end of the fracture. Although the Kirschner wire is in the medullary cavity, it is not in the center of the medullary cavity. In this case, it enters the bone marrow cavity. The elasticity of Kirschner wire will produce a force in a certain direction, resulting in the possibility of angulation of the fracture end. Similarly, we believe that Kirschner wires entering the medullary cavity through the radial styloid process or Lister’s tubercle to treat distal radius DMJ fractures will face similar problems. The new method proposed in this study maximized the use of the distal end of fracture, gently advanced Kirschner wire into the posterior distal end of the medullary cavity perpendicular to the epiphysis of the distal radius to drill out, and then reversed Kirschner wire to easily advance the radial medullary cavity, which was more in line with biomechanical principles.

Elastic intramedullary nailing technique has also been used by some scholars to treat distal radius DMJ fractures [7,8]. However, retrograde elastic intramedullary nails are routinely used to treat DMJ fractures, and the entry point is short from the fracture end and cannot give full play to the supporting role of elastic intramedullary nail [5,19]. In addition, elastic nails will push the proximal end of the fracture to the opposite side when they enter, resulting in angulation deformity [7]. To solve these problems, Joulié et al proposed to change the conventional needle insertion point from the lateral to dorsal medial side of the radius, which can improve therapeutic effect to a certain extent [8]. Cai et al proposed that satisfactory lines of force, stable fixation, and less displacement can be obtained by prebending the tail of elastic nail 90° during nail insertion [7]. Varga et al proposed short, double elastic nails for the treatment of this fracture and obtained good functional and imaging results [10]. Du et al introduced a new technique for the treatment of distal radius DMJ fractures with antegrade elastic intramedullary nailing [11]. However, antegrade placement of elastic nails had the risk of injuring the radial nerve [2]. The new method proposed in this study is easier and safer to perform and more affordable than various elastic intramedullary nail techniques. Kirschner wires did not need to be prebent like intramedullary nails to smoothly enter the medullary canal and cause abnormal biomechanics at the prebend. In addition, the intramedullary nail technique required general anesthesia and re-incision of skin during a second operation to remove the internal fixation.

Although the open reduction plate screw fixation technique can achieve improved anatomical reduction [5], it has the disadvantages of a large surgical incision, obvious scar, high cost, and the need for a second operation for removal. External fixator has also been used to treat distal radius DMJ fractures [11]. Although it is also a minimally invasive method, it is relatively cumbersome and expensive compared with the new method proposed in this study, and its postoperative care is also challenging.

This new technique has the following limitations. Firstly, there may be a risk of iatrogenic epiphyseal injury, which can be minimized technically. In our study, none of the 15 children developed growth imbalance due to epiphyseal injury. This is related to the fact that the Kirschner wire we chose was a smooth Kirschner wire with a diameter of <2.0 mm [20], and the insertion direction of the Kirschner wire was perpendicular to the epiphysis [20]. In addition, the operation was completed in a single attempt. Secondly, there may be a risk of damaging the surrounding soft tissue when the Kirschner wire passes through the skin. Therefore, we tended to keep the wrist at maximum palpation during the operation while the assistant touched and pushed away the tendons on both sides to prevent the Kirschner wire penetrating the tendon. Fortunately, there were no related complications in any patient in this study. Lastly, there may be minor fracture displacement, which is not necessarily adverse to the union. In our study, 15 cases healed within the normal time frame, which may be related to the fact that the fretting at the end of fracture can stimulate callus formation [16,19]. Some of the study’s other limitations include the small sample size and short follow-up time. Therefore, multicenter, large-sample, and long-term follow-up studies are required to confirm the advancement and reliability of this technique in the future. Moreover, the lack of prospective comparative studies between this new technique and other traditional techniques is another limitation of its validation.

Conclusions

To sum up, we consider that limited open reduction and transepiphyseal intramedullary fixation with Kirschner wire is effective in treating distal radius DMJ fractures in children, which has the advantages of simple surgical operation, short time, small incision, and less radiation exposure. Therefore, this new method is worthy of being an alternative for treating distal radius diaphyseal metaphyseal junction fractures.

Figures

Figure 1. (A–D) Intraoperative procedures(A) The dorsal longitudinal incision was made to expose the fracture end. (B) The smooth Kirschner wire was inserted antegradely from the fracture end into the medullary cavity of distal radius and 2 thumbs touched and pushed the tendons on both sides to avoid the Kirschner wire penetrating the tendon. (C) Under direct vision, reduction was performed and Kirschner wires were retrogradely inserted into the proximal radial medullary cavity. (D) The incision length was about 2 cm. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).

Figure 1. (A–D) Intraoperative procedures(A) The dorsal longitudinal incision was made to expose the fracture end. (B) The smooth Kirschner wire was inserted antegradely from the fracture end into the medullary cavity of distal radius and 2 thumbs touched and pushed the tendons on both sides to avoid the Kirschner wire penetrating the tendon. (C) Under direct vision, reduction was performed and Kirschner wires were retrogradely inserted into the proximal radial medullary cavity. (D) The incision length was about 2 cm. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).  Figure 2. (A–D) Preoperative, intraoperativeThe radius was fixed with a 2.0 mm in diameter Kirschner wire. (A, B) Preoperative fluoroscopy; (C, D) Intraoperative fluoroscopy. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).

Figure 2. (A–D) Preoperative, intraoperativeThe radius was fixed with a 2.0 mm in diameter Kirschner wire. (A, B) Preoperative fluoroscopy; (C, D) Intraoperative fluoroscopy. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).  Figure 3. (A–D) Postoperative fluoroscopy(A, B) Postoperative fluoroscopy; (C, D) Six months after the surgery, fluoroscopy showed no physeal arrest. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).

Figure 3. (A–D) Postoperative fluoroscopy(A, B) Postoperative fluoroscopy; (C, D) Six months after the surgery, fluoroscopy showed no physeal arrest. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).  Figure 4. (A–D) Clinical outcome at the last follow-up showed excellent function(A, B) No limitation of forearm rotation function; (C, D) No limitation of wrist joint function. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).

Figure 4. (A–D) Clinical outcome at the last follow-up showed excellent function(A, B) No limitation of forearm rotation function; (C, D) No limitation of wrist joint function. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China). References

1. Huang Q, Su F, Wang ZM, Prying reduction with mosquito forceps versus limited open reduction for irreducible distal radius-ulna fractures in older children: A retrospective study: BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2021; 22(1); 147

2. Lieber J, Schmid E, Schmittenbecher PP, Unstable diametaphyseal forearm fractures: Transepiphyseal intramedullary Kirschner-wire fixation as a treatment option in children: Eur J Pediatr Surg, 2010; 20(6); 395-98

3. Lieber J, Sommerfeldt DWDiametaphyseal forearm fracture in childhood. Pitfalls and recommendations for treatment: Unfallchirurg, 2011; 114(4); 292-99 [in German]

4. Kubiak R, Aksakal D, Weiss C, Is there a standard treatment for displaced pediatric diametaphyseal forearm fractures?: A STROBE-compliant retrospective study: Medicine (Baltimore), 2019; 98(28); e16353

5. Kose O, Deniz G, Yanik S, Open intramedullary Kirschner wire versus screw and plate fixation for unstable forearm fractures in children: J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong), 2008; 16(2); 165-69

6. Joulie S, Laville JM, Salmeron F, Posteromedial elastic stable intra-medullary nailing (ESIN) in volarly displaced metaphyso-diaphyseal distal radius fractures in child: Orthop Traumatol Surg Res, 2011; 97(3); 330-34

7. Cai H, Wang Z, Cai H, Prebending of a titanium elastic intramedullary nail in the treatment of distal radius fractures in children: Int Surg, 2014; 99(3); 269-75

8. Du M, Han J, Antegrade elastic stable intramedullary nail fixation for paediatric distal radius diaphyseal metaphyseal junction fractures: A new operative approach: Injury, 2019; 50(2); 598-601

9. Di Giacinto S, Pica G, Stasi A, The challenge of the surgical treatment of paediatric distal radius/forearm fracture: K wire vs plate fixation – outcomes assessment: Med Glas (Zenica), 2021; 18(1); 208-15

10. Varga M, Jozsa G, Fadgyas B, Short, double elastic nailing of severely displaced distal pediatric radial fractures: A new method for stable fixation: Medicine (Baltimore), 2017; 96(14); e6532

11. Li J, Rai S, Tang X, Fixation of delayed distal radial fracture involving metaphyseal diaphyseal junction in adolescents: A comparative study of crossed Kirschner-wiring and non-bridging external fixator: BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2020; 21(1); 365

12. Joeris A, Lutz N, Blumenthal A, The AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures (PCCF): Acta Orthop, 2017; 88(2); 123-28

13. Price CT, Scott DS, Kurzner ME, Malunited forearm fractures in children: J Pediatr Orthop, 1990; 10(6); 705-12

14. Children W: Rockwood and Wilkins’ fractures in children

15. Hoel G, Kapandji AIOsteosynthesis using intra-focal pins of anteriorly dislocated fractures of the inferior radial epiphysis: Ann Chir Main Memb Super, 1995; 14(3); 142-56 [in French]

16. Choi KY, Chan WS, Lam TP, Percutaneous Kirschner-wire pinning for severely displaced distal radial fractures in children. A report of 157 cases: J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1995; 77(5); 797-801

17. Yung PS, Lam CY, Ng BK, Percutaneous transphyseal intramedullary Kirschner wire pinning: A safe and effective procedure for treatment of displaced diaphyseal forearm fracture in children: J Pediatr Orthop, 2004; 24(1); 7-12

18. Lee SC, Han SH, Rhee SY, Percutaneous transphyseal pin fixation through the distal physis of the ulna in pediatric distal fractures of the forearm: J Orthop Trauma, 2013; 27(8); 462-66

19. Huber RI, Keller HW, Huber PM, Flexible intramedullary nailing as fracture treatment in children: J Pediatr Orthop, 1996; 16(5); 602-5

20. Peterson HA, Partial growth plate arrest and its treatment: J Pediatr Orthop, 1984; 4(2); 246-58

Figures

Figure 1. (A–D) Intraoperative procedures(A) The dorsal longitudinal incision was made to expose the fracture end. (B) The smooth Kirschner wire was inserted antegradely from the fracture end into the medullary cavity of distal radius and 2 thumbs touched and pushed the tendons on both sides to avoid the Kirschner wire penetrating the tendon. (C) Under direct vision, reduction was performed and Kirschner wires were retrogradely inserted into the proximal radial medullary cavity. (D) The incision length was about 2 cm. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).

Figure 1. (A–D) Intraoperative procedures(A) The dorsal longitudinal incision was made to expose the fracture end. (B) The smooth Kirschner wire was inserted antegradely from the fracture end into the medullary cavity of distal radius and 2 thumbs touched and pushed the tendons on both sides to avoid the Kirschner wire penetrating the tendon. (C) Under direct vision, reduction was performed and Kirschner wires were retrogradely inserted into the proximal radial medullary cavity. (D) The incision length was about 2 cm. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China). Figure 2. (A–D) Preoperative, intraoperativeThe radius was fixed with a 2.0 mm in diameter Kirschner wire. (A, B) Preoperative fluoroscopy; (C, D) Intraoperative fluoroscopy. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).

Figure 2. (A–D) Preoperative, intraoperativeThe radius was fixed with a 2.0 mm in diameter Kirschner wire. (A, B) Preoperative fluoroscopy; (C, D) Intraoperative fluoroscopy. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China). Figure 3. (A–D) Postoperative fluoroscopy(A, B) Postoperative fluoroscopy; (C, D) Six months after the surgery, fluoroscopy showed no physeal arrest. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).

Figure 3. (A–D) Postoperative fluoroscopy(A, B) Postoperative fluoroscopy; (C, D) Six months after the surgery, fluoroscopy showed no physeal arrest. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China). Figure 4. (A–D) Clinical outcome at the last follow-up showed excellent function(A, B) No limitation of forearm rotation function; (C, D) No limitation of wrist joint function. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China).

Figure 4. (A–D) Clinical outcome at the last follow-up showed excellent function(A, B) No limitation of forearm rotation function; (C, D) No limitation of wrist joint function. This figure was created using WPS software (Windows version, 11.1.0., China). In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variation of Medical Comorbidities in Oral Surgery Patients: A Retrospective Study at Jazan ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943884

08 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Evaluation of Foot Structure in Preschool Children Based on Body MassMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943765

15 Apr 2024 : Laboratory Research

The Role of Copper-Induced M2 Macrophage Polarization in Protecting Cartilage Matrix in OsteoarthritisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943738

07 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 179 Male Third- and Fourt...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943468

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952