17 June 2023: Clinical Research

Burden of COVID-19 on Mental Health of Resident Doctors in Poland

Wojciech Stefan ZgliczyńskiDOI: 10.12659/MSM.940208

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940208

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The study aim was to assess the prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia among resident doctors in Poland during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The online anonymous survey was conducted among Polish resident doctors attending obligatory specialization courses organized by the Center of Postgraduate Medical Education between 2020 and 2021. The psychological impact of COVID-19 was measured using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21). The sleep problems were assessed using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).

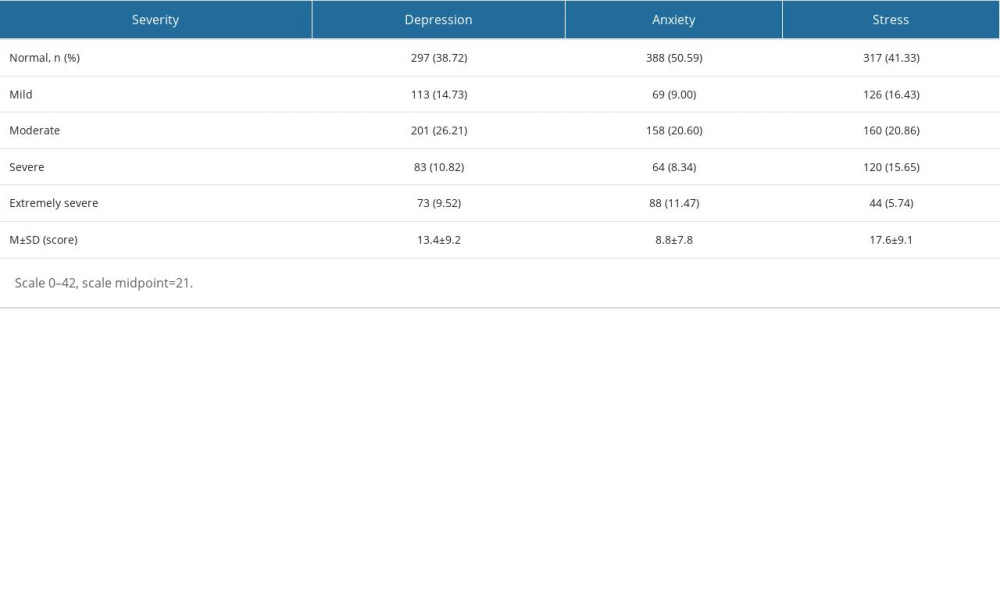

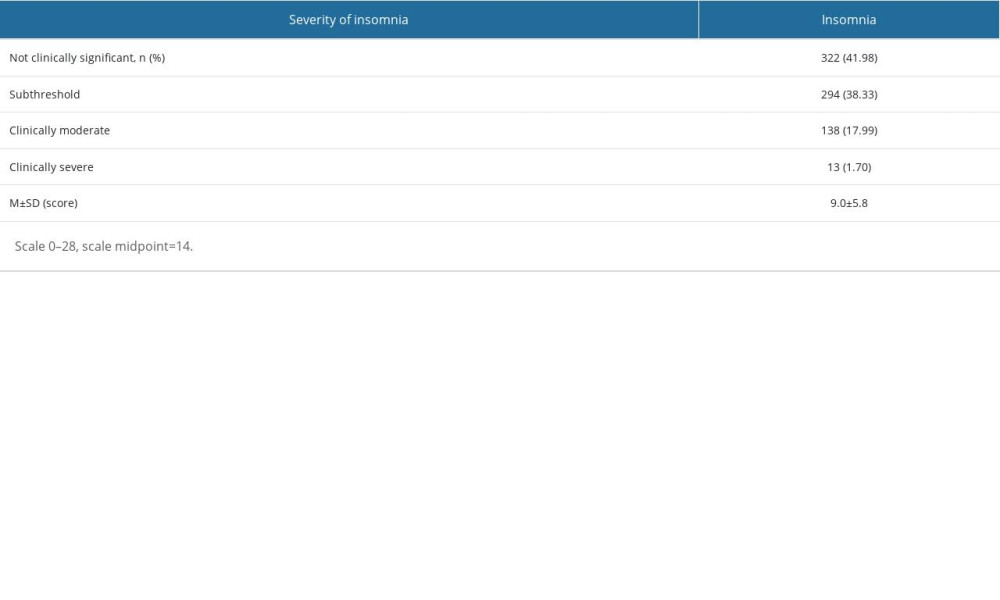

RESULTS: Among 767 resident doctors participating in the study there were substantial levels of depression (14.7% mild, 26.2% moderate, 10.8% severe, and 9.5% extremely severe), anxiety (9.0% mild, 20.6% moderate, 8.3% severe, and 11.5% extremely severe), and stress (16.4% mild, 20.9% moderate, 15.7% severe, and 5.7% extremely severe), as well as substantial incidence of insomnia (58.0%), (38.3% subthreshold, 17.9% clinically moderate, and 1.7% clinically severe). Female doctors, physicians working directly with COVID-19 patients, and those who had COVID-19 themselves were at higher risk of depression, stress, and anxiety. Sleep disorders were more prevalent among doctors in surgical specializations, as well as those working directly with COVID-19 patients.

CONCLUSIONS: The COVID-19 pandemic in Poland appears to have negatively affected doctors’ mental health. High levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia indicate that systemic solutions are needed. A spectrum of interventions should be explored to mitigate further strain on the physicians' psychological health in the post-pandemic work environment. It is necessary to focus on groups at particular risk, such as women, front-line doctors, doctors in health crisis, and residents in selected fields of medicine.

Keywords: COVID-19, Stress, Physiological, Poland, Depression, Anxiety, Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders, Physicians, Humans, Female, COVID-19, Mental Health, Pandemics, SARS-CoV-2, Stress, Psychological

Background

Health services are only as effective as the persons responsible for delivering them [1]. Human resources are the most important part of the health care system. The output of the health care system depends heavily on the knowledge, skills, and motivation of the personnel responsible for delivering services [2], which is why the physical and psychological conditions of medical staff are crucially important. Ongoing studies on this topic are needed due to changing needs, possibilities, and differences in social, economic, and cultural conditions. One of the greatest challenges in the recent years was the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected entire populations in different areas.

It is indicated that the pandemic and associated isolation measures had significant negative impacts on mental health [3–6]. The pandemic also impacted negatively medical personnel, including doctors. Deterioration of physicians’ mental health status was greater than in the general population [7–9]. The psychological wellbeing of doctors after the COVID-19 epidemic therefore becomes a critical issue that needs to be fully understood, controlled, and addressed, as it affects not only themselves but also their work.

Numerous systematic reviews regarding mental health condition of health care workers, including sleep disorders, have been performed [10–15]. They confirm not only that the impact of the pandemic on mental health was a universal topic experienced globally, but also affected doctors in various countries to a different extent. It is worth emphasizing that researchers have long indicated that doctors are a professional group particularly vulnerable to mental health problems [16].

In Poland, the issue of psychological decline among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic was the subject of several studies. These studies were conducted in different populations using different measurement tools: 97 doctors of unspecified specialties using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FOC-6) and Job Satisfaction Scale (BJSS) [17]; 848 medical professionals, including 649 physicians not specified in terms of specialization using General Health Questionnaire 28 (GHQ-28) [18]; 80 orthopedic surgeons, original questionnaire [19]; and 235 different medical professionals using Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [20]. To date, studies have not been focused on doctors undergoing specialization (resident doctors). Such studies appear to be particularly warranted because resident doctors have largely been front-line doctors working in contact with COVID-19 patients, and very often work night shifts, which is a risk factor for sleep disorders. Their crucial role in managing patients with coronavirus [21], as well as the disruptions in specialization training program caused by the pandemic, may have contributed to the deterioration of mental health [22]. Residents, who are usually in the beginning of their medical career, may have limited professional experience and resilience in dealing with professionally challenging situations, and thus may be more vulnerable to stress [23]. Resident doctors oftentimes combine making first steps in a health profession with personal milestones such as early-stage parenthood, which may result in additional stress and sleep disorders. To date, no studies have been published on potential differences between doctors in Poland in various specialties.

The importance of conducting such research is of particular relevance given the characteristics of the Polish health care system, which has relatively few doctors compared to other EU countries, resulting in high individual workloads. On average, a doctor in Poland in 2018 provided 5892 consultations vs 1939 in the EU [24]. In Poland, the health expenditure in 2020 was 6.5% of GDP while the EU average was 10.9% of GDP. Moreover, in Poland the COVID-19 pandemic took an exceptionally severe course, with the highest numbers of COVID-19 deaths and excess deaths in the EU – between March 2020 and October 2022, COVID-19 mortality in Poland and excess mortality were 3127 and 5892 per 1 million population, respectively, while the EU average was 2152 and 3196 per 1 million, respectively [25].

All these factors combined contributed to creating a particularly stressful environment for healthcare staff, including resident doctors, who were often exposed to unprecedented working conditions and whose coping mechanisms were severely strained.

The aim of the study was to assess the prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia among Polish resident doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. The specific aim was to determine the impact of demographic factors, job characteristics, and personal experience of COVID-19 on doctors’ mental health.

Material and Methods

PARTICIPANTS:

The study group consisted of doctors participating in online public health courses at the School of Public Health, Center of Postgraduate Medical Education in Warsaw (CMKP), Poland from November 2020 to October 2021. Participation in the course is obligatory for each physician undergoing specialty training in Poland. The participants represent different health care facilities from all over the country. All 1041 physicians attending courses in this period were eligible to participate in the study and were approached by researchers. Inclusion criteria for the study were being a resident doctor undergoing specialization training, and informed consent to participate in the study obtained via online form. The lack of agreement made it impossible to participate in the study, as the questionnaire was set to begin with the consent form. We did not collect e-mail addresses or other data to identify respondents, which was to ensure the respondents’ anonymity. Eventually, 767 complete survey questionnaires were used for the analysis (response rate 73.7%). In total, there were about 26 000 resident physicians in Poland at that time.

The research tool was an online questionnaire designed to ensure anonymity prepared in Polish using Google Forms. The online questionnaire consisted of 4 sections. The first section included characteristics of the respondents (gender, age), and their professional characteristics (place of work, type and status of specialization). Second part included respondents’ personal experience of the COVID-19 pandemic (personal experience with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, contacts with infected patients). The third section used the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and the last section used Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). Considering the wide application of these tools in research, it is possible to compare the results between different professional groups and different countries.

QUESTIONS REGARDING COVID-19 PERSONAL EXPERIENCE:

For the purpose of our study we created 10 questions concerning COVID-19 personal experience, i.e. 1) Have you been quarantined due to contact with a person infected with SARS-CoV-2?, 2) Have you ever had symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection?, 3) Have you ever had a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2?, 4) Have you ever been in isolation or quarantine due to SARS-CoV-2?, 5) Do you have daily contact with SARS-CoV-2 infected patients at work?, 6) Do you work in a ward dedicated to the care of people with COVID-19?, 7) What influence on your work does the COVID-19 pandemic have?, 8) Does your workplace situation related to the COVID-19 pandemic make you feel stressed?, 9) What influence on your mental wellbeing does the COVID-19 pandemic have? and 10) What influence on your sleep quality does the COVID-19 pandemic have?. The answers to questions 1–6 were ‘yes’ or ‘no’ (except for the second question with ‘don’t know’ as a third option). Questions 7–10 required the subjects to choose 1 answer on the Likert scale; for example, question 7: strongly negative, negative, neutral, positive, strongly positive; question 8: definitely no, no, neutral, yes, definitely yes; and Questions 9 and 10: strongly negative, negative, rather negative, neutral, rather positive, positive, strongly positive.

DEPRESSION, ANXIETY, AND STRESS SCALE (DASS-21):

The DASS-21 is a rating scale that consists of a total of 21 items divided into 3 subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress, with each subscale consisting of 7 items [26,27]. For each item, the respondent rates the severity of their symptoms from 0 to 3. The total score for each subscale was calculated as the sum of the scores for the answers to the 7 items, multiplied by 2. A respondent can obtain from 0 to 42 points for each subscale. The higher the score is, the higher the severity of depression, anxiety, or stress. The resulting ratings are classified as normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe. The score categories for the interpretation of every subscale are different. Depression: normal (0–9), mild (10–13), moderate (14–20), severe (21–27), and extremely severe (28–42). Anxiety: normal (0–7), mild (8–9), moderate (10–14), severe (15–19), extremely severe (20–42). Stress: normal (0–14), mild (15–18), moderate (19–25), severe (26–33), and extremely severe (34–42).

The individual subscales in our study had Cronbach’s alphas above 0.8 and strong inter-correlation coefficients among the items: depression (alpha=0.897, r=0.560), anxiety (alpha=0.832, r=0.425), and stress (alpha=0.890 and r=0.539), which ensures reliability and internal coherence.

INSOMNIA SEVERITY INDEX (ISI):

The ISI is a rating scale that consists of a total of 7 questions [28]. For each question, a respondent rates the severity of their symptoms from 0 to 4. The total score for the scale is calculated as the sum of the scores for the answers to the 7 questions. A respondent can obtain a total of 0 to 28 points. The higher the score is, the higher the severity of insomnia. The interpretation is as follows: no clinically significant insomnia (0–7), subthreshold insomnia (8–14), clinically moderate insomnia (15–21), and clinically severe insomnia (22–28).

Cronbach’s alpha 0.872 and average inter-correlation coefficient r=0.508 among the 7 questions ensure reliability and internal coherence.

RECRUITMENT:

The link to the questionnaire was delivered to participants in an online form by a researcher at the beginning of each course delivered by the CMKP. The researcher informed participants about the survey purpose and technical details. The participants could decide whether to take part in the survey or not. Anonymous questionnaires were collected during every public health course (participants had 3 days to return a completed form). The survey was distributed only among physicians who were by default all eligible to participate (target group), since enrollment for the courses was conducted by the CMKP based on identification as a ‘resident doctor’.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The data were statistically analyzed using STATISTICA 13 software.

Minimum and maximum values and mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were estimated for numerical variables, while absolute numbers (n) and percentages (%) were used for categorical variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient r was used to assess correlations among severities of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia.

The 2-sample unpaired

For analysis of variance, the F test was used to compare depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia severities, between workplaces, between workplace locations, between 5 most frequent specializations, and between 3 answers to 1 question concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. Pearson’s correlation coefficient r was also used to assess correlations among depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia severities with age and with COVID-19 influence on work, mental health, sleep quality, and stress related to work. The significance level was assumed at 0.05.

ETHICS STATEMENT:

According to the Act of 5 December 1996 on the professions of physicians and dentists (Journal of Laws of 2021, item 790 as amended), the presented study was not a medical experiment. The study is in line with the Institutional Ethics Committee and the Helsinki Declaration (1964). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Public Health, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education. Permission to perform the study was granted from the Dean of the School of Public Health, CMKP.

Results

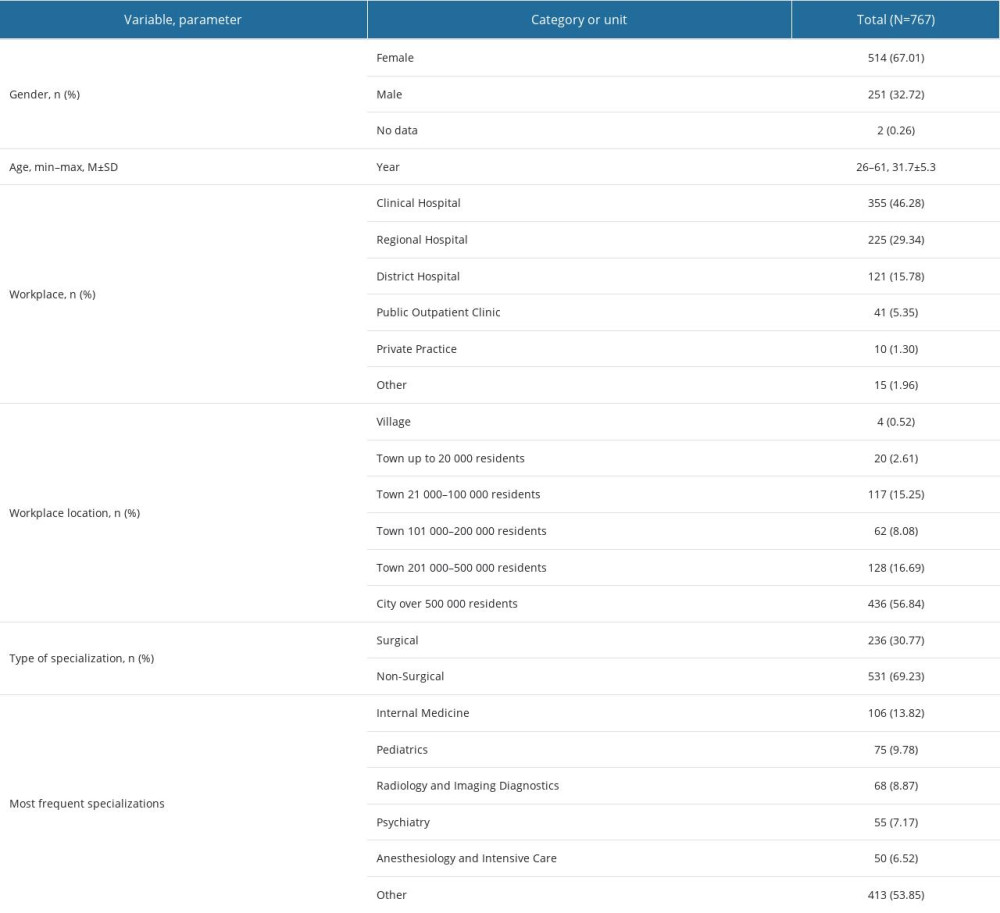

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY GROUP:

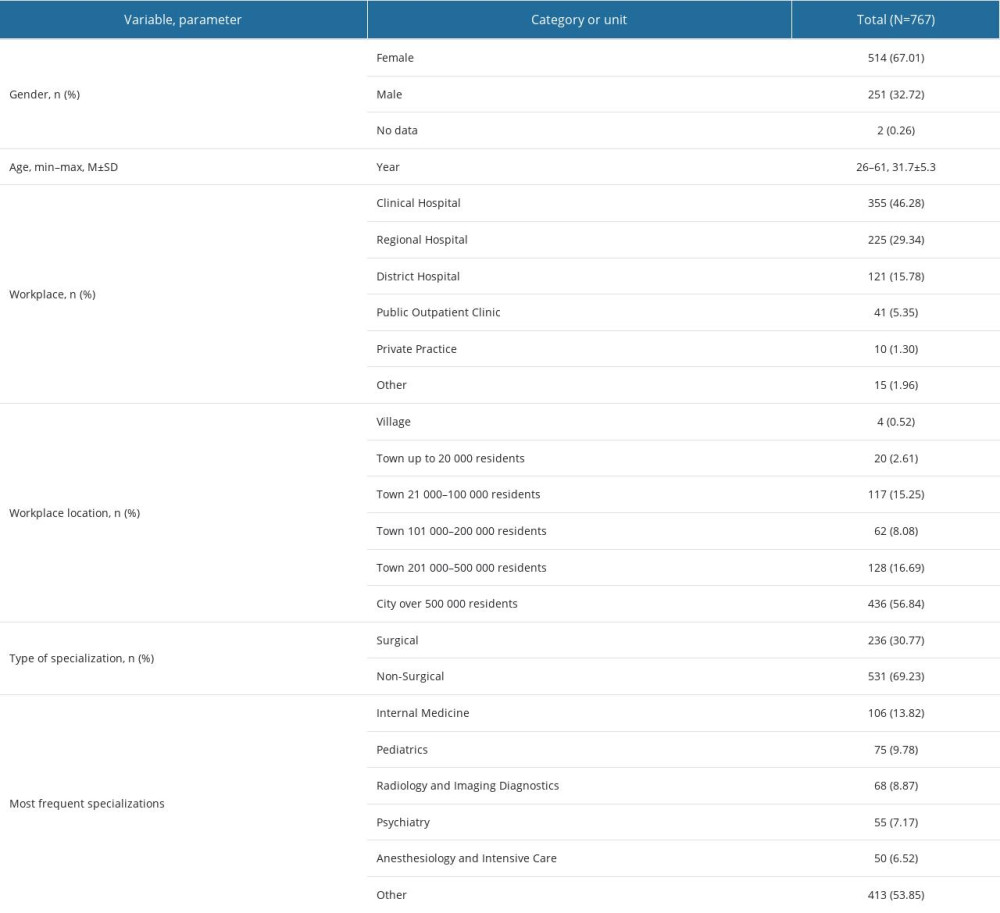

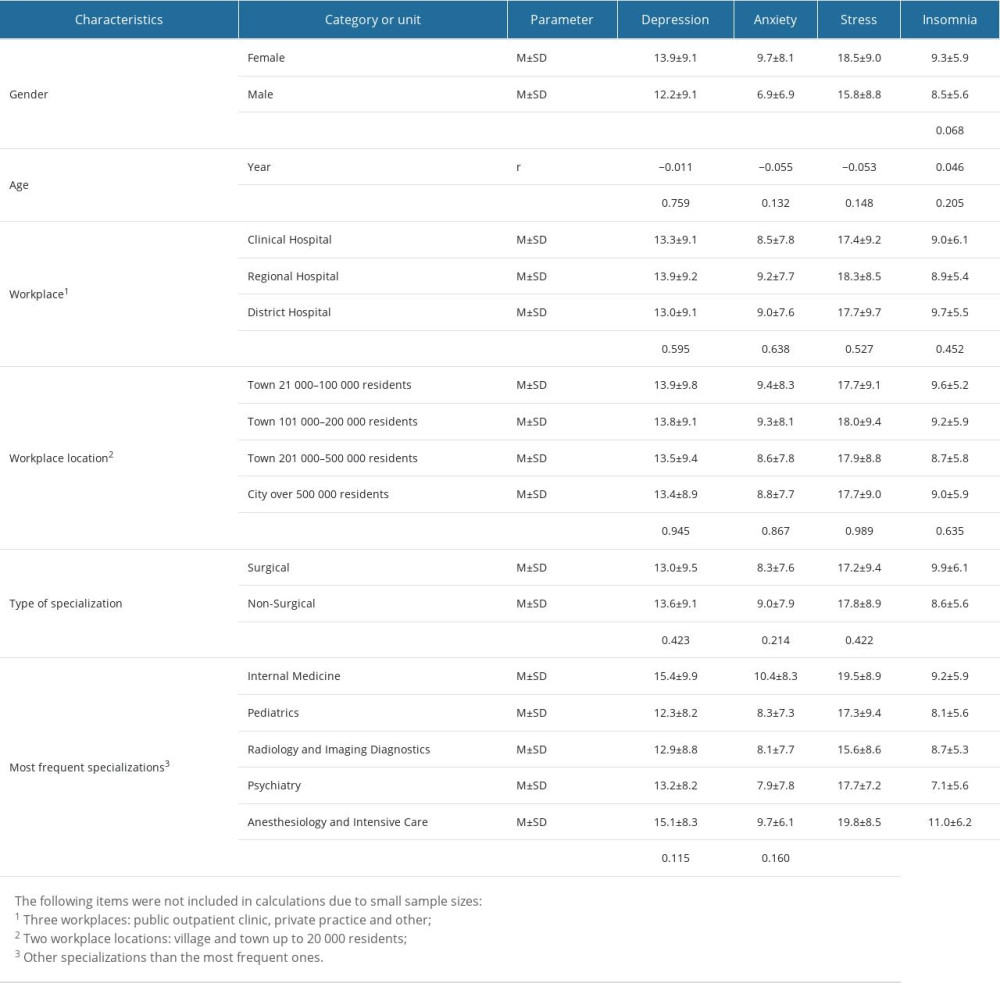

Table 1 presents demographic and professional characteristics of the surveyed medical doctors. They were aged between 26 and 61 years, 31.7±5.3 years on average, and 2/3 of the respondents were women. Almost half of the respondents worked in clinical hospitals and the majority worked in cities with over 500 000 residents (57%).

Most respondents had non-surgical specializations (69% non-surgical vs 31% surgical). The most common specializations were: internal medicine, pediatrics, radiology and imaging diagnostics, psychiatry, anesthesiology, and intensive care, and 54% of respondents had other specializations.

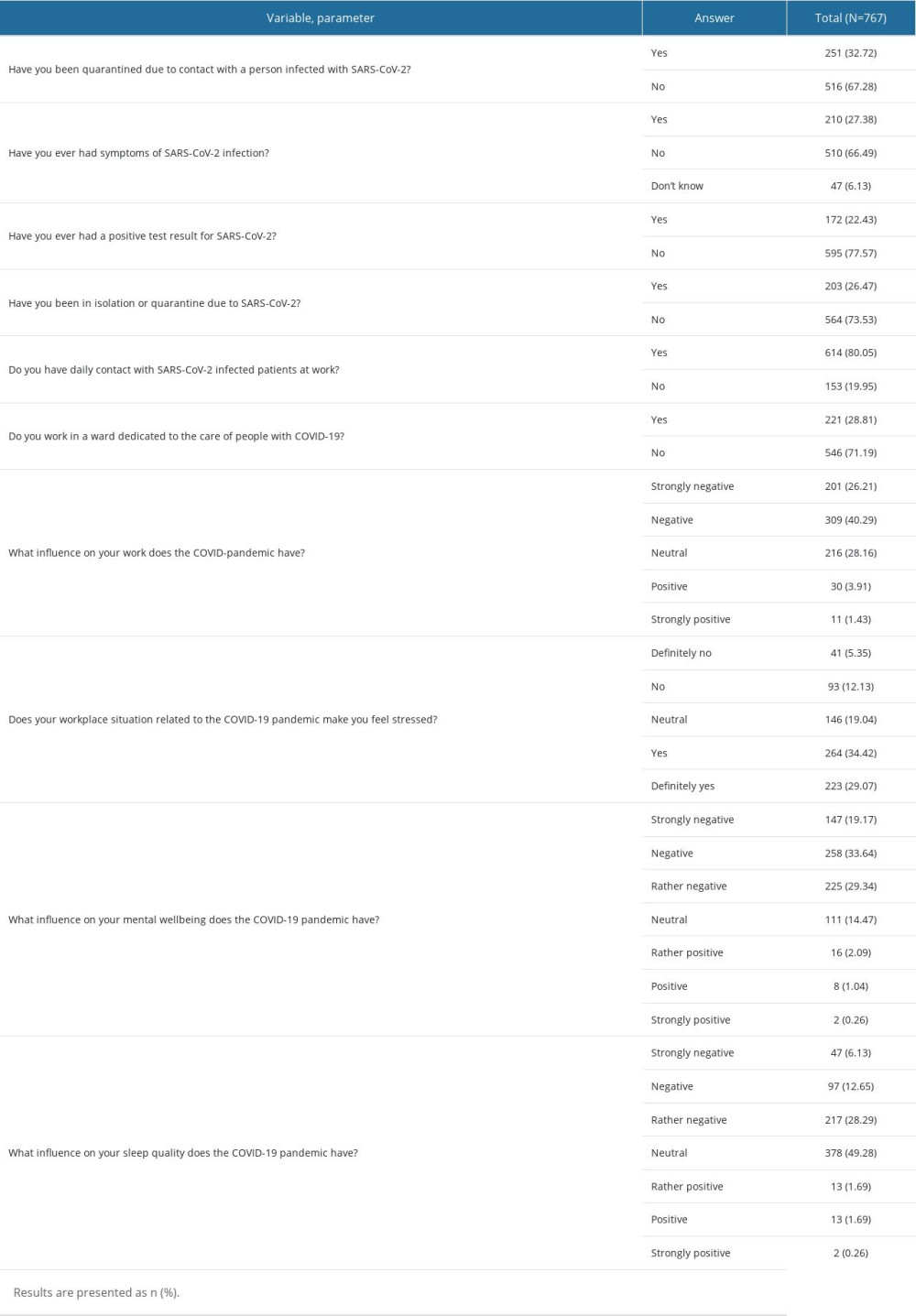

COVID-19 EXPERIENCES IN THE STUDY GROUP:

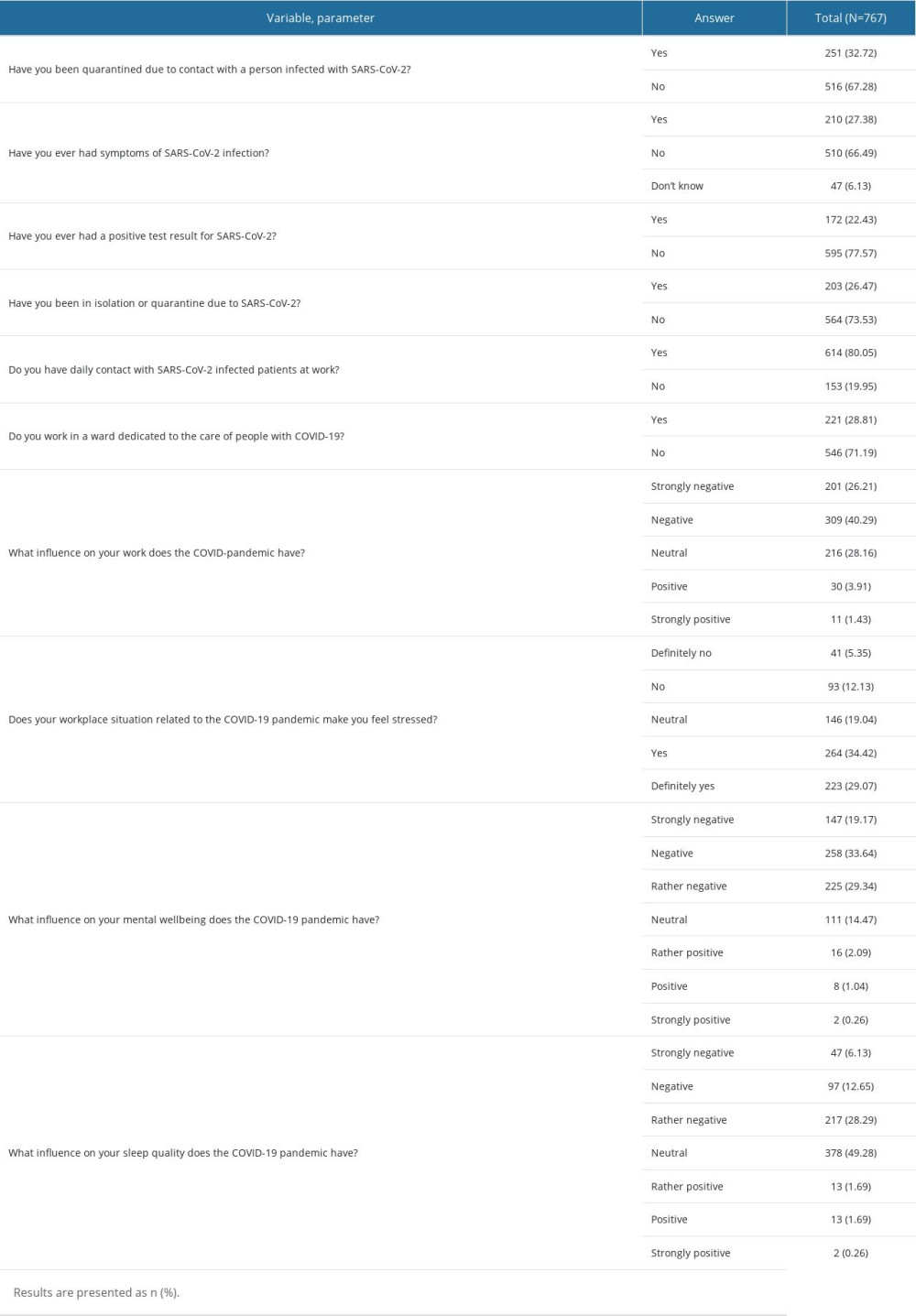

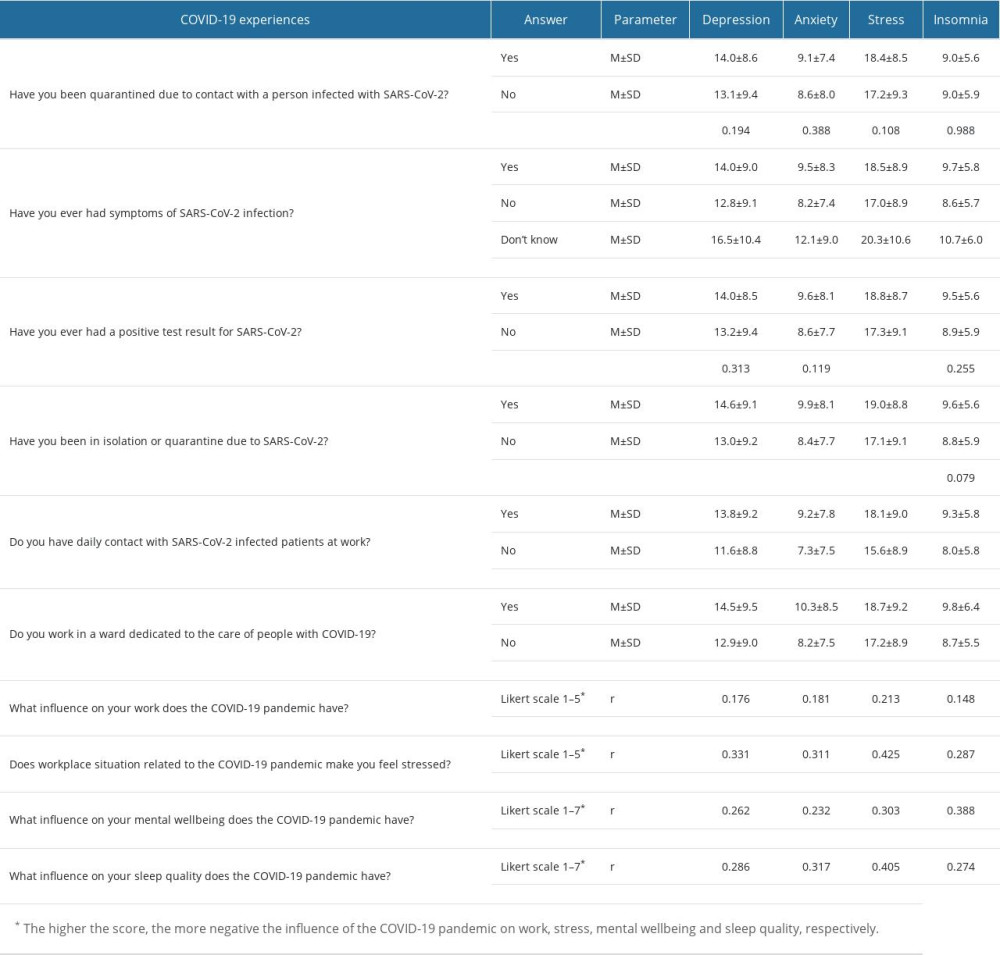

Table 2 presents the summary of the responses to the questions concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. One-third of the respondents (33%) had been quarantined due to contact with a person infected with SARS-CoV-2; 27% of the respondents had experienced symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection, while 66% had not and 6% had not known; 22% of the respondents had had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2; 26% had been in isolation or quarantine due to SARS-CoV-2; 80% had had daily contact with SARS-CoV-2-infected patients at work; and 29% had worked in a ward dedicated to the care of patients with COVID-19.

Most of the respondents indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had negative or strongly negative influence on their work (40% and 26%, respectively). Most of the respondents considered their workplace situation in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic to cause their stress (34% said “yes” and 29% said “definitely yes”). Most respondents believed that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on their mental wellbeing (19% strongly negative, 34% negative, 29% rather negative). Almost half of the respondents said that the COVID-19 pandemic had no impact on their sleep quality (49%), while for 47% the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on their sleep quality (6% strongly negative, 13% negative, 28% rather negative).

MENTAL HEALTH BURDEN IN THE STUDY GROUP:

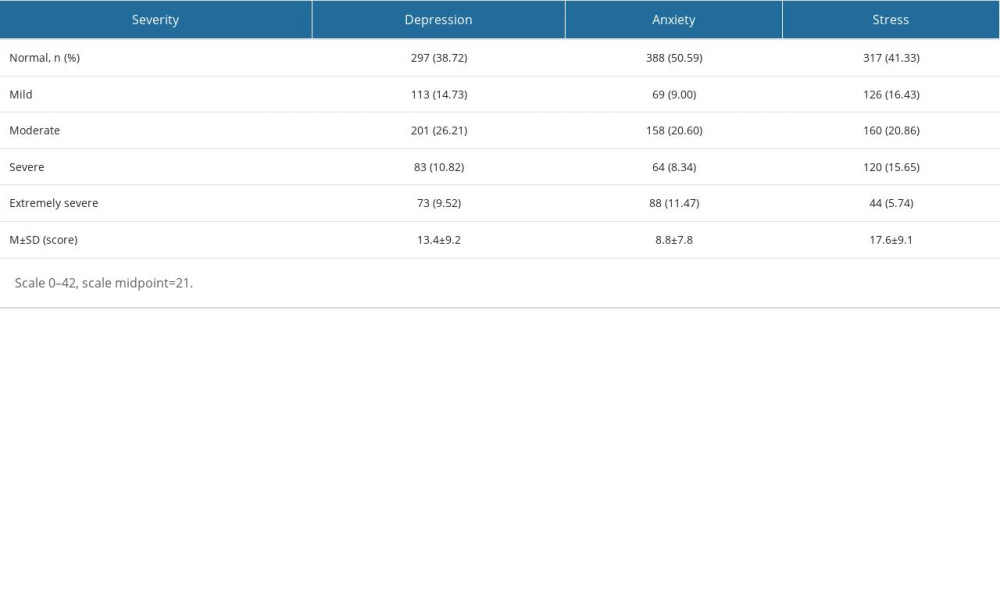

Table 3 presents the results of measurements of depression, anxiety, and stress severity among the surveyed medical doctors using the DASS-21 scale. The largest proportion of participants received scores classified as ‘normal‘ for depression (39%), anxiety (51%), and stress (41%), although a notable proportion scored in the ‘severe’ to ‘extremely severe’ ranges (20% for depression, 20% for anxiety, and 21% for stress). Mean scores indicate that participants were on average scoring within the moderate range for depression, anxiety, and stress.

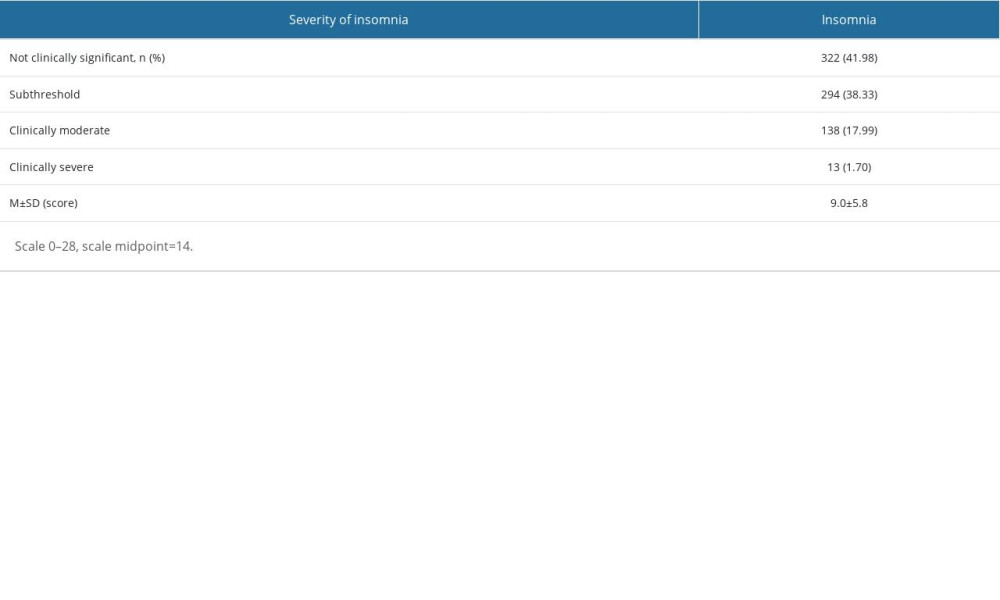

Table 4 presents the results of measurements of insomnia severity in the surveyed medical doctors using the Insomnia Severity Index. The largest proportion of participants (42%) scored in a ‘normal’ range (not experiencing insomnia) and clinically severe insomnia was found in 1.7%. Mean severity of insomnia was 9, which means subthreshold level of insomnia, on average.

Mutual correlations between depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia severity were significant in each pair (

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN DEMOGRAPHIC AND PROFESSIONAL CHARACTERISTICS, AND MENTAL HEALTH:

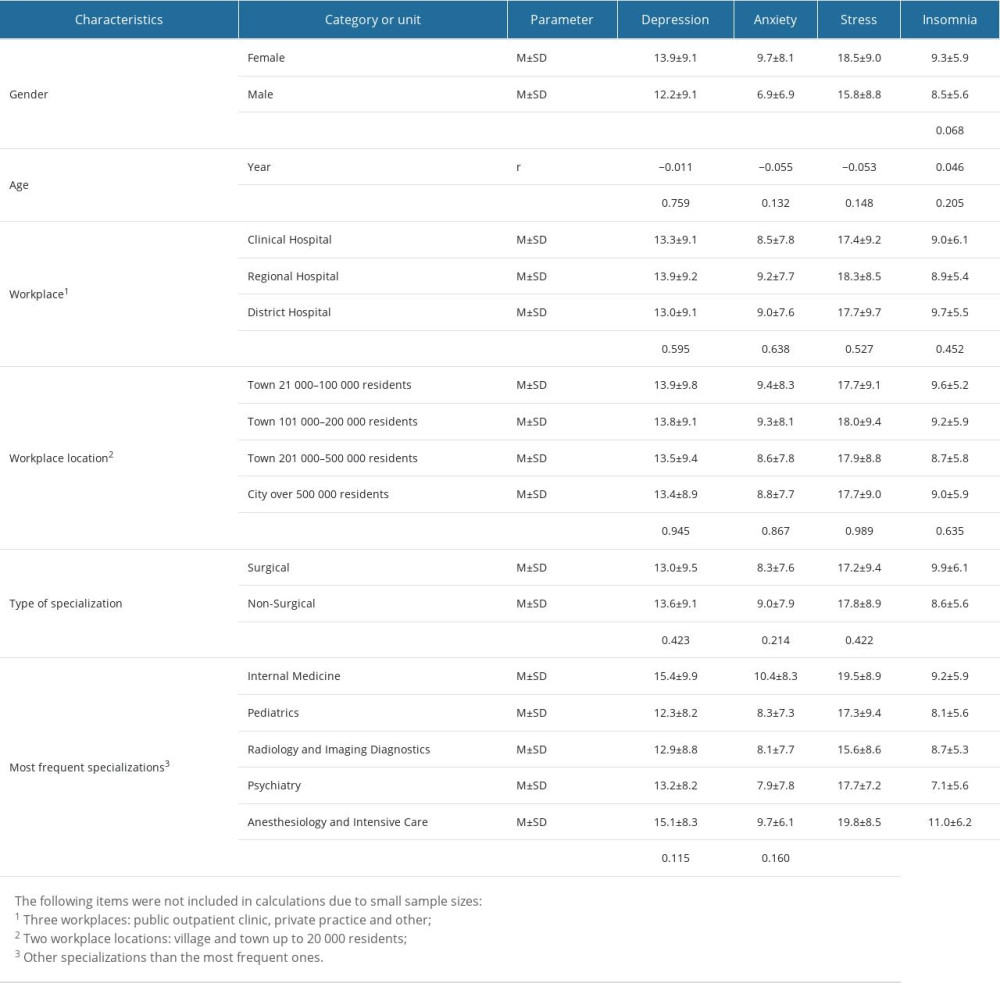

Table 5 presents the severity of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia related to demographic and professional characteristics of the study group. Female medical doctors had significantly higher severity of depression, anxiety, and stress than male medical doctors, while the severity of insomnia did not differ significantly between genders. The severity of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia in the study group did not correlate with age and did not differ significantly between the types of workplaces or between workplace locations.

The respondents doing surgical specializations had significantly higher severity of insomnia than those doing the non-surgical ones, while the severity of depression, anxiety, and stress did not differ significantly between the respondents doing surgical and non-surgical specializations.

Regarding the most frequent specializations, the highest severity of stress was among respondents doing specialization in internal medicine or anesthesiology and intensive care. Moreover, the highest severity of insomnia was in anesthesiology and intensive care. The severity of depression and anxiety did not differ significantly between the 5 most frequent specializations analyzed.

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN COVID-19 EXPERIENCES AND MENTAL HEALTH:

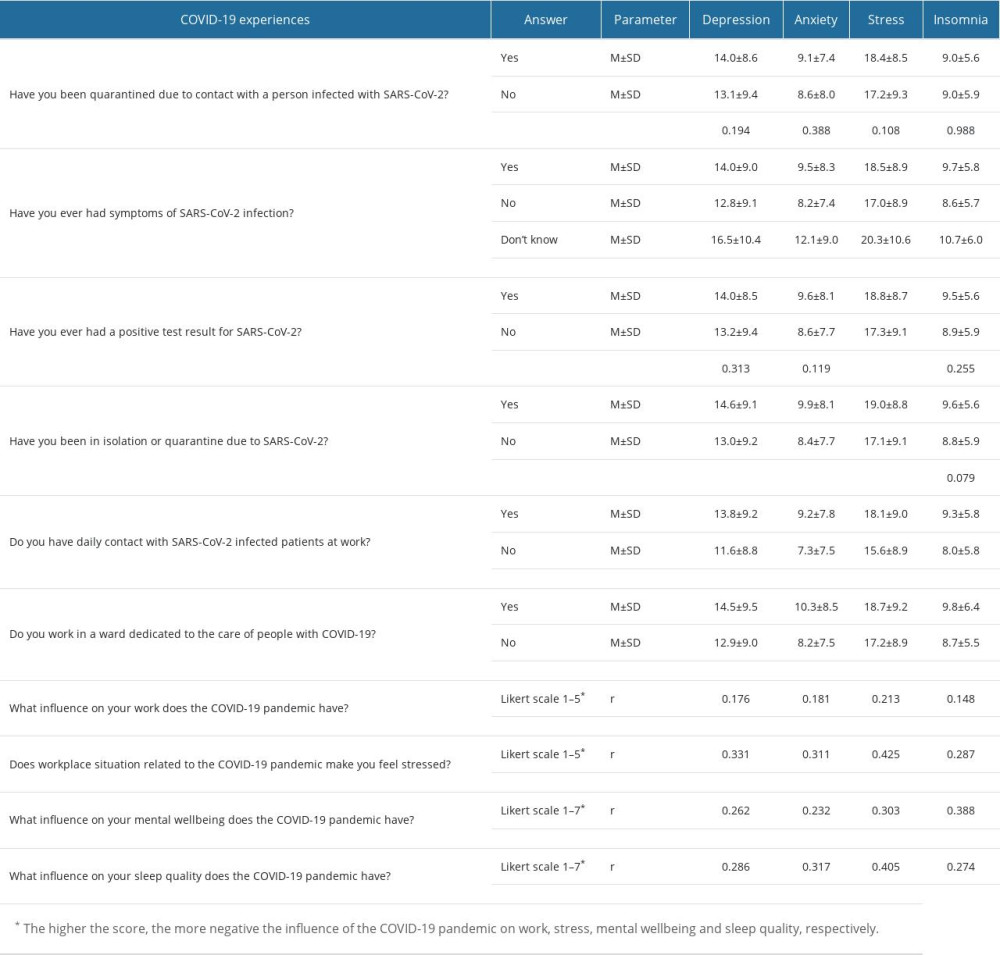

Table 6 presents the severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia related to COVID-19 experiences of the study group. The severity of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia in the study group did not differ significantly between the respondents who had been quarantined due to contact with a person infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the respondents who had not been quarantined.

The severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia was significantly higher if the respondents did not know whether they had ever had the symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Respondents who had ever had a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 had more severe stress than those who had not. However, the severity of depression, anxiety, and insomnia did not differ significantly between the respondents who had ever had a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 and those who had never had it.

The respondents who had ever been isolated or quarantined due to SARS-CoV-2 had more severe depression, anxiety, and stress than those who had not. However, the severity of insomnia did not differ significantly between the respondents who had been isolated or quarantined and those who had not. The severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia was also significantly higher if the respondents had daily contact with SARS-CoV-2-infected patients at work and for those who worked in a ward dedicated to the care of people with COVID-19. A more negative influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the respondents’ work, mental health, sleep quality, and stress related to work was associated with higher severity of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia, on average.

Discussion

The characteristics of the respondents presented in this research reflect the characteristics of doctors undergoing specialization in Poland [29]. Due to the participation of respondents in courses that are obligatory for all doctors, it can be assumed that the study group was representative of the population of doctors undergoing specialization in Poland. To the authors’ best knowledge, this research is one of the first and largest studies assessing the levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and severity of insomnia of Polish resident doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Depression, anxiety, and stress were measured using the DASS-21 scale. Resident doctors participating in the study commonly reported symptoms of depression (61.3%), anxiety (49.4%), and stress (58.7%). In comparison with the results of the study conducted in the general population in Poland with the same tools and within a similar time period, the level of depression among doctors was higher by 10.9 percentage points (p.p.), the level of anxiety was higher by 6.0 p.p., and the level of stress was lower by 2.6 p.p. [30]. This may show higher psychological harm among physicians. A study conducted in Iran found even higher levels of depression, stress, and anxiety among COVID-19 patients [31]. Such a gradation in the occurrence of stress is reported in the literature in the context of other countries and populations [14].

The results of surveys conducted among doctors and other medical personnel in other countries using the DASS-21 tool yielded varying results. A study conducted in Belgium [32] found levels of depression, stress, and anxiety among physicians, at 52.0%, 23.5%, and 37.4%, respectively, which was lower than in Poland. In a study conducted in Turkey [33] among ophthalmologists, levels of depression, anxiety, and stress were 65%, 56.9%, and 43%, respectively, which was slightly higher than in Poland. Importantly, the results of these studies presented significantly higher rates in the DASS-21 tool among resident doctors. In contrast, studies conducted in Egypt and Saudi Arabia showed levels of depression, anxiety, and stress among doctors, at 73.8%, 60.7%, and 60.2%, respectively [34], which was distinctly higher than in Poland.

Sleep problems in doctors were measured using the ISI scale. Sleep disturbances occurred in 58.2% of respondents. These results were very similar to another study conducted among medical personnel in Poland, where sleep problems were found in 58% of staff [20], but the results were noticeably higher than in the general Polish population, where sleep disturbances were found in 44.7% [30].

The results of other studies conducted among doctors and other medical personnel in other countries using the ISI, similarly to the DASS-21, yielded mixed results. The results were lower than in Egypt (67.7%) [44] but higher in Turkey (46.9%) [33] and considerably higher than those of medical professionals in India (31.9%) [36] and China (36.1%) [37].

Our study showed that being a female resident was a significant predictor of anxiety and stress. This finding agrees with other surveys, such as from Turkey [33,38], Croatia [39], and Asia [11,40]. A worldwide cross-sectional analysis has shown that in all cohorts and countries, women had higher levels of anxiety and mood disorders than men [41]. These results may imply that with an increasing proportion of women among practicing doctors in Poland, the importance of this issue will be rising.

The mental health status of doctors, including levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, as well as the prevalence of sleep problems in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide, was also investigated using instruments other than DASS-21 and ISI, again, there were large differences in the results. There are at least several reasons for this, including socio-cultural differences between countries, differences in the organization of work, differences between doctors according to their place of work and specialization, and differences in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic and the timing of the survey. As a result of these differences, it seems advisable to conduct country-specific and population-specific studies.

Our analysis confirms that working directly with COVID-19 patients was a risk factor for higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress. This relationship was observed in other studies using the DASS-21 tool conducted in Italy [42] and the USA [43], but was not present in Belgium [32]. Similar relationships to those observed by us were reported in studies using other tools to measure depression, stress, and anxiety, including surveys conducted among health care workers in Poland [20] and Turkey [38], as well as Greece [44] and China [45]. Our analysis confirms also that working directly with COVID-19 patients was a risk factor for insomnia, which agrees with other surveys, such as from Turkey [38] and China [46].

Our study revealed that having symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as well as having been isolated or quarantined due to SARS-CoV-2 was connected with higher risk of depression, anxiety, and stress, which to some extent corresponds with findings from the general population [47]. This may suggest that the negative effects of the pandemic in the mental health dimension of the population match or in some cases even surpass the physical health spectrum.

Our analyses show that the higher the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the respondents’ work, mental health, sleep quality, and stress related to workplace situation was, the higher the severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia, on average. It is worth highlighting that the study analyzed the impact of the pandemic on mental health. Most surveyed doctors (66%) felt that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative or strongly negative impact on their work and 63% felt stressed as a result. More than 80% of respondents felt that the pandemic had a negative impact on their mental wellbeing and 47% indicated a negative impact on the quality of their sleep. To some extent, this is supported by other studies indicating that health care workers’ perceived psychological burden increases as the pandemic continues [48,19]. On the other hand, adaptation cannot be ruled out, as with the passage of time there is familiarization with the situation and the levels of stress, depression, and anxiety may decrease [49]. It may be that due to the high importance of individual factors (psychological stamina) and differences in access to social support or willingness to seek professional support, the 2 scenarios outlined above are not mutually exclusive.

The results of our survey can be treated as an alarm signal and a pivotal point for systemic actions to be taken by decision-making entities at the level of the central public authorities, local governments, and individual medical institutions. This is further supported by the fact that potential courses of action have been widely described in the literature [48,50–52]. Direct superiors seem to have a special role in this context. Proposed actions should include expressing acknowledgement of the challenging work conditions, regular work interviews by supervisors confident in speaking about mental health, active monitoring of the most vulnerable groups, and inclusive discussions to help develop site-specific and tailored mental health toolboxes. These actions widely used in military organizations give good results [50,51].

It is worth analyzing and adapting solutions to Polish organizational and cultural conditions. As the effects of the psychological burden associated with the COVID-19 pandemic may persist for a prolonged period of time [53] and may lead to the development of further psychological problems such as secondary traumatic stress [54], undertaking effective measures is more than urgent.

The results indicate that continuous monitoring of the mental state of doctors is necessary. Conducting such surveys among doctors may have the added value of increasing doctors’ awareness of the prevalence of mental health problems and thus contribute to greater openness in talking about their own difficulties. From the HR management perspective, any actions which can improve the mental health of doctors can have positive impacts on productivity and resilience by lowering sickness absence and presenteeism, as well as lowering the risk of burnout.

This study has certain limitations. First, it was cross-sectional and does not provide information on the evolution of the results over time. Secondly, we did not recruit a control group from the general population. Thirdly, we did not assess previous mental health history. Finally, although the scales can provide some diagnostic clues, the actual diagnosis of mood and anxiety disorders can only be made after a clinical examination. It cannot be ruled out that the results obtained are underestimated, which may be due to the tendency to conceal mental disorders.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic in Poland most likely imposed negative impacts on doctors’ mental health. Substantial levels of depression, stress, and, to a lesser extent, anxiety, as well as insomnia indicate that systemic solutions are needed. A spectrum of interventions should be explored to mitigate further strain on the physicians’ psychological health in the post-pandemic work environment. Interventions, due to limited resources, should primarily focus on groups at particular risk, such as female doctors, front-line doctors, doctors in health crisis, and residents of selected fields of medicine. When creating teams of doctors to work with specific groups of patients, it is important to consider their mental endurance. As the risks, needs, and circumstances may be subject to change, follow-up studies are needed to assess the evolution of the situation documented. Building public awareness of the nature of the problem and its scale is an important first step.

Tables

Table 1. Demographic and professional characteristics of the study group. Table 2. COVID-19 experiences in the study group.

Table 2. COVID-19 experiences in the study group. Table 3. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale in the study group.

Table 3. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale in the study group. Table 4. Insomnia Severity Index in the study group.

Table 4. Insomnia Severity Index in the study group. Table 5. Severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia (scores) related to the demographic and professional characteristics of the study group.

Table 5. Severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia (scores) related to the demographic and professional characteristics of the study group. Table 6. Severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia (scores) related to COVID-19 experiences in the study group.

Table 6. Severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia (scores) related to COVID-19 experiences in the study group.

References

1. Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, A universal truth: No health without a workforce Forum Report: Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, Recife, 2013, Brazil Geneva, Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/hrh_universal_truth

2. : The world health report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance, 2000, Geneva, World Health Organization

3. Pfefferbaum B, North CS, Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: N Engl J Med, 2020; 383(6); 510-12

4. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence: Lancet, 2020; 395(10227); 912-20

5. Fiorillo A, Gorwood P, The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice: Eur Psychiatry, 2020; 63(1); e32

6. Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis: J Affect Disord, 2021; 281; 91-98

7. Ornell F, Halpern SC, Kessler FHP, Narvaez JCM, The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals: Cad Saude Publica, 2020; 36(4); e00063520

8. Maciaszek J, Ciulkowicz M, Misiak B, Mental health of medical and non-medical professionals during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional nationwide study: J Clin Med, 2020; 9(8); 2527

9. Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China: Psychother Psychosom, 2020; 89(4); 242-50

10. Mahmud S, Hossain S, Muyeed A, The global prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and, insomnia and its changes among health professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis: Heliyon, 2021; 7(7); e07393

11. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Brain Behav Immun, 2020; 88; 901-7 [Erratum in: Brain Behav Immun. 2021;92: 247]

12. Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H, The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta-analysis: Psychiatry Res, 2020; 291; 113190

13. Sahebi A, Nejati-Zarnaqi B, Moayedi S, The prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: An umbrella review of meta-analyses: Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2021; 107; 110247

14. Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V, Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Psychiatry Res, 2020; 293; 113382

15. Salari N, Khazaie H, Hosseinian-Far A, The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-regression: Hum Resour Health, 2020; 18(1); 100

16. Brooks SK, Gerada C, Chalder T, Review of literature on the mental health of doctors: Are specialist services needed?: J Ment Health, 2011; 20(2); 146-56

17. Dymecka J, Filipkowski J, Machnik-Czerwik A, Fear of COVID-19: Stress and job satisfaction among Polish doctors during the pandemic: Postep Psychiatr Neurol, 2021; 30(4); 243-50

18. Babicki M, Szewczykowska I, Mastalerz-Migas A, The mental well-being of health care workers during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic – a nationwide study in Poland: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(11); 6101

19. Kołodziej Ł, Ciechanowicz D, Rola H, The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Polish orthopedics, in particular on the level of stress among orthopedic surgeons and the education process: PLoS One, 2021; 16(9); e0257289

20. Wańkowicz P, Szylińska A, Rotter I, Assessment of mental health factors among health professionals depending on their contact with COVID-19 patients: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020; 17(16); 5849

21. Civantos AM, Byrnes Y, Chang C, Mental health among otolaryngology resident and attending physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: National study: Head Neck, 2020; 42(7); 1597-609

22. Strangio A, Leo I, Spaccarotella CAM, Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the formation of fellows in training in cardiology: J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown), 2021; 22(9); 711-15

23. Adams MA, Brazel M, Thomson R, Lake H, The mental health of Australian medical practitioners during COVID-19: Australas Psychiatry, 2021; 29(5); 523-28

24. OECD/European Union: Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle, 2020, Paris, OECD Publishing

25. OECD/European Union, Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle, 2022, Paris, OECD Publishing

26. Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample: Psychological Assessment, 1998; 10(2); 176

27. Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF, Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales: Psychology Foundation of Australia, 1996

28. Morin CM: Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management, 1993, Guilford press

29. Zgliczyński WS, Węgrzyn Z, Ruiz M, Specialty training system in Poland in 2011–2018 according to the Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education register data: Wiedza Medyczna, 2020; 2(1); 1-8

30. Hoffmann K, Kopciuch D, Bońka A, The Mental Health of Poles during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2023; 20(3); 2000

31. Moayed MS, Vahedian-Azimi A, Mirmomeni G, Depression, anxiety, and stress among patients with COVID-19: A cross-sectional study: Adv Exp Med Biol, 2021; 1321; 229-36

32. Tiete J, Guatteri M, Lachaux A, Mental health outcomes in healthcare workers in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 care units: A cross-sectional survey in Belgium: Front Psychol, 2021; 11; 612241

33. Durmaz Engin C, Senel Kara B, The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on practice patterns and psychological status of ophthalmologists in Turkey: Cureus, 2021; 13(7); e16614

34. Arafa A, Mohammed Z, Mahmoud O, Depressed, anxious, and stressed: What have healthcare workers on the frontlines in Egypt and Saudi Arabia experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic?: J Affect Disord, 2021; 278; 365-71

35. Elkholy H, Tawfik F, Ibrahim I, Mental health of frontline healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 in Egypt: A call for action: Int J Soc Psychiatry, 2021; 67(5); 522-31

36. Sunil R, Bhatt MT, Bhumika TV, Weathering the storm: Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on clinical and nonclinical healthcare workers in India: Indian J Crit Care Med, 2021; 25(1); 16-20

37. Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: Front Psychiatry, 2020; 11; 306

38. Şahin MK, Aker S, Şahin G, Karabekiroğlu A, Prevalence of depression, anxiety, distress and insomnia and related factors in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey: J Community Health, 2020; 45(6); 1168-77

39. Vilovic T, Bozic J, Vilovic M, Family physicians’ standpoint and mental health assessment in the light of COVID-19 pandemic – a nationwide survey study: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(4); 2093

40. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019: JAMA Netw Open, 2020; 3(3); e203976

41. Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys: Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2009; 66(7); 785-95

42. Lenzo V, Quattropani MC, Sardella A, Depression, anxiety, and stress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak and relationships with expressive flexibility and context sensitivity: Front Psychol, 2021; 12; 623033

43. Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, Dale AM, Work-related and personal factors associated with mental well-being during the COVID-19 response: Survey of health care and other workers: J Med Internet Res, 2020; 22(8); e21366 [Erratum in: J Med Internet Res. 2021:23(4):e29069]

44. Tzenetidis V, Papathanasiou I, Tzenetidis N, Effort reward imbalance and insomnia among greek healthcare personnel during the outbreak of COVID-19: Mater Sociomed, 2021; 33(2); 124-30

45. Que J, Shi L, Deng J, Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study in China: Gen Psychiatr, 2020; 33(3); e100259

46. Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: Front Psychiatry, 2020; 11; 306

47. Wang S, Quan L, Chavarro JE, Associations of depression, anxiety, worry, perceived stress, and loneliness prior to infection with risk of post-COVID-19 conditions: JAMA Psychiatry, 2022; 79(11); 1081-91 [Erratum in: JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(11):1141]

48. Teo I, Chay J, Cheung YB, Healthcare worker stress, anxiety and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore: A 6-month multi-centre prospective study: PLoS One, 2021; 16(10); e0258866

49. Sampaio F, Sequeira C, Teixeira L, Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on nurses’ mental health: A prospective cohort study: Environ Res, 2021; 194; 110620

50. Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S, Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: BMJ, 2020; 368; m1211

51. Greenberg N, Brooks SK, Wessely S, Tracy DK, How might the NHS protect the mental health of health-care workers after the COVID-19 crisis?: Lancet Psychiatry, 2020; 7(9); 733-34

52. Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed: Lancet Psychiatry, 2020; 7(3); 228-29

53. Schwartz RM, McCann-Pineo M, Bellehsen M, The impact of physicians’ COVID-19 pandemic occupational experiences on mental health: J Occup Environ Med, 2022; 64(2); 151-57

54. Orrù G, Marzetti F, Conversano C, Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(1); 337

Tables

Table 1. Demographic and professional characteristics of the study group.

Table 1. Demographic and professional characteristics of the study group. Table 2. COVID-19 experiences in the study group.

Table 2. COVID-19 experiences in the study group. Table 3. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale in the study group.

Table 3. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale in the study group. Table 4. Insomnia Severity Index in the study group.

Table 4. Insomnia Severity Index in the study group. Table 5. Severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia (scores) related to the demographic and professional characteristics of the study group.

Table 5. Severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia (scores) related to the demographic and professional characteristics of the study group. Table 6. Severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia (scores) related to COVID-19 experiences in the study group.

Table 6. Severity of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia (scores) related to COVID-19 experiences in the study group. In Press

15 Apr 2024 : Laboratory Research

The Role of Copper-Induced M2 Macrophage Polarization in Protecting Cartilage Matrix in OsteoarthritisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943738

07 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 179 Male Third- and Fourt...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943468

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952