25 March 2022: Clinical Research

Retrospective Study of the Etiology, Laboratory Findings, and Management of Patients with Urinary Tract Infections and Urosepsis from a Urology Center in Silesia, Southern Poland Between 2017 and 2020

Zygmunt F. Gofron1ABCDEFG*, Malgorzata AptekorzDOI: 10.12659/MSM.935478

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935478

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Recent studies have shown that up to 25% of sepsis cases originate in the urinary tract. Urosepsis can be associated with cystitis, lower urinary tract infections (UTIs), and upper UTIs and is most commonly caused by gram-negative bacteria. This retrospective study from a urology center in southern Poland, was conducted between 2017 and 2020 and aimed to investigate the causes, microbiology laboratory findings, and management in 138 patients with UTIs and urosepsis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: Records of patients with UTIs with urosepsis admitted to the Urology Department of the hospital in Silesia, Poland, between 2017 and 2020 were analyzed retrospectively, and clinical and laboratory data were evaluated.

RESULTS: The 138 included patients were admitted to the hospital between 2017 and 2020. The median age of patients was 67 (20-94) years, and 59.9% (82/137) were men. The most common reasons for admission to the Urology Department were hydronephrosis due to dysfunction of urinary drainage in 36.5% (50/137) of patients and hydronephrosis due to urolithiasis in 22.6% (31/137) of patients. The main etiological agents responsible for the development of urosepsis were strains of Enterobacteriaceae in 85% of patients, of which 41.4% (48/116) produced extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL), accounting for 35.0% (48/137) of patients with urosepsis. In 83.3% (80/96) of patients, the pathogen cultured from the urine was identical to that cultured from the blood.

CONCLUSIONS: The identification of an increasing prevalence of urosepsis associated with ESBL-producing gram-negative rods from this single-center study highlights the importance of infection monitoring, rapid diagnosis, and multidisciplinary patient management.

Keywords: beta-Lactamases, Sepsis, Urinary Tract Infections, Aged, 80 and over, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Humans, Male, Poland, Urology

Background

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common in urological Emergency Departments and are considered the most common bacterial healthcare-associated infection [1]. UTIs account for about 40% of outpatient and 10% to 20% of inpatient infections [2] and can include the lower and upper urinary tract and can even lead to sepsis [1–3]. The number of cases increases annually as a result of an aging population, increasing antibiotic resistance, and use immunomodulating therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunosuppressants [4,6,7]. The antibiotic resistance of etiological agents usually complicates treatment strategies [8]. The present state of development of antibiotic resistance mechanisms is alarming [9]. The presence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing gram-negative rods with resistance to frequently used antibiotics is steadily increasing [10]. Bacteria with enzymes that are mainly discovered include

Disturbance of the urine outflow due to urolithiasis, urinary tract obstruction, benign prostate enlargement, urethral stricture, and congenital anomalies are common underlying risk factors of urosepsis development. Interventions and surgery performed on the urinary tract can also lead to urosepsis [15]. Advanced age and comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, kidney failure, and immune deficiencies, are considered risk factors of urosepsis [6,16,17].

Sepsis is a systemic host response to an infection that causes acute organ dysfunction, which is mostly related to the source of infection [4,18].

The new sepsis definition uses the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scoring system, in which a score higher than 2 points is associated with an in-hospital mortality rate greater than 10% and is considered a sepsis indicator. Quick SOFA (qSOFA) is an easy to perform important clinical score whose criteria include a respiratory rate higher that 22/breaths/min, altered mental state (Glasgow coma scale <15), and systolic blood pressure lower than 100 mm Hg. If a suspected patient demonstrates at least 2 of these criteria, they should be identified as being at risk of developing sepsis [18].

The definition of urosepsis according to Bonkat et al [5] is the life-threatening condition coming from the urinary tract or male genital organs. Urosepsis requires prompt recognition and intervention [5].

Despite the new management of sepsis, multicenter studies in the United States between 1997 and 2000 showed high mortality rates of sepsis, which ranged from 17.9% to 27.8% [7]. The latest data confirm that, among all sepsis cases, an estimated 9% to 31% are urosepsis [8]. Despite the increase in knowledge and the recommendations, urosepsis should still be considered as a serious threat with a high mortality rate. Owing to the small number of recent publications on urosepsis, in particular on cultured etiological factors, and the inconclusive data on the prevalence of ESBL-producing strains, we investigated cases of UTI and urosepsis. Therefore, this retrospective study from a urology center in Silesia in southern Poland was conducted between 2017 and 2020 and aimed to investigate the etiology, laboratory findings, and management of 138 patients with UTIs and urosepsis.

Material and Methods

ETHICAL APPROVAL:

This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Medical University of Silesia Bio-Ethics Committee [approval no. PCN/0022/KB1/25/I/20], Bogusław Okopień MD, PhD). We collected research data without any identifiers so that individual participation was anonymous and the data collected could not be linked to the individuals.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS:

A total of 138 patients diagnosed with UTIs with urosepsis between January 2017 and June 2020 were identified. The inclusion criteria for the analysis were a UTI with urosepsis, defined as a positive blood culture in patients with urology comorbidities and the suspicion of sepsis based on a qSOFA score >2 at admission. Patients were initially identified by screening the electronic health records for positive blood cultures obtained on admission by testing with a VITEK 2 system (bioMérieux, Marcy L’Etoile, France). The exclusion criteria were a qSOFA score <2 at admission, lack of medical documentation not allowing the patient to be included in the statistical analysis, and a negative blood culture.

STUDY DESIGN:

Our study was a retrospective chart review of electronic records conducted at an 86-bed specialized urology center in Katowice (Silesian region, southern Poland). The study was conducted between January 2017 and June 2020 and included charts of adult patients admitted to the Urology Department who were suspected of having urosepsis. Patient characteristics, including age and sex, were also collected for further statistical analysis. Clinical data were evaluated, including presence of urologic comorbidities, length of hospitalization, duration of treatment with antibiotics, time of appropriate antibiotic therapy, and continuation of antibiotic therapy after discharge. Appropriate antimicrobial therapy was defined as using agents (oral or intravenous) according to the results of antibiotic susceptibility testing. The time to appropriate antimicrobial therapy was defined as the time interval starting from obtaining blood cultures to receiving the first dose of appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

During the study, we collected information on urological comorbidities and the etiological factors of urosepsis. We also obtained patient demographic data and laboratory test results at admission as well as data about clinical outcomes. We compared the patients after separating them into 2 groups: patients with infection caused by ESBL-producing strains and patients with sepsis caused by non-ESBL-producing strains.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The results were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and TIBCO Statistica version 13 (data analysis software system,

Results

PATIENTS CHARACTERISTICS AND COMORBIDITIES:

A total of 138 UTI patients with urosepsis were enrolled in this study (with clinically confirmed sepsis defined as at least 2 points on the qSOFA scale). One of these patients was excluded from the statistical analysis for formal reasons; therefore, 137 patient charts were analyzed. The median age of the 137 patients was 67.0 (range 20–94) years, and 59.1% (81/137) were men. There was a significant difference in age between men and women. The median age of men was 70.0 (range 22–90) years, which was higher than the median age of women at 66.0 (range 20–94) years, and the difference was statistically significant (

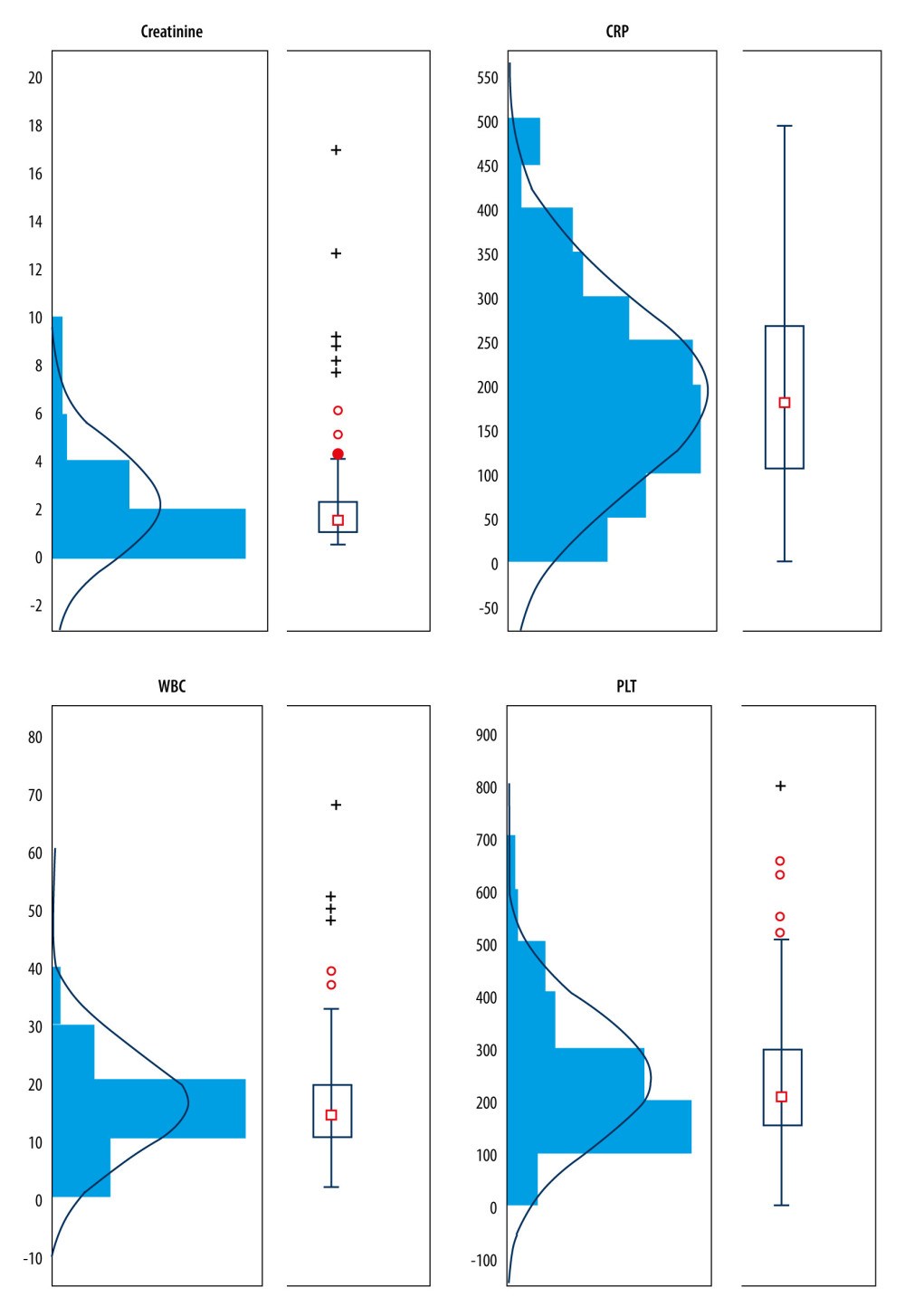

On admission for each patient, biochemical testing was performed, including a full blood count with white blood cell (WBC) count, platelet count (PLT), C-reactive protein (CRP), and creatinine level. Data of all patients with at least 1 deviation in laboratory tests on admission are presented in Figure 1. The creatinine level in men was significantly higher (P=0.0463; median 1.68; range 0.77–16.81) than that in women (median 1.47; range 0.59–9.22). No statistically significant difference was observed between values of biochemical parameters (WBC, CRP, PLT levels) between women and men.

On admission, 34.3% (47/137) of patients required minor urological surgery involving the replacement of the nephrostomy/urostomy catheter or a regular bladder catheter. About 28.5% (39/137) of patients required an endoscopic procedure involving the decompression of hydronephrosis by placing a urethral stent. Most of these procedures (61.5% [24/39]) were in patients with hydronephrosis caused by ureterolithiasis; 17.5% (24/137) of patients required hydronephrosis decompression with the percutaneous nephrostomy procedure. These patients were mainly admitted to the hospital because of hydronephrosis of an undefined etiology, 54.2% (13/24). A total of 10.2% (14/137) of patients required an endoscopic procedure without urethral stenting, such as coagulation of a bleeding mucosa of the bladder, owing to hematuria with life-threatening anemia, 3.6% (5/137) of patients required open surgery, and only 5.8% (8/137) of patients did not require any surgery.

BACTERIAL ISOLATES:

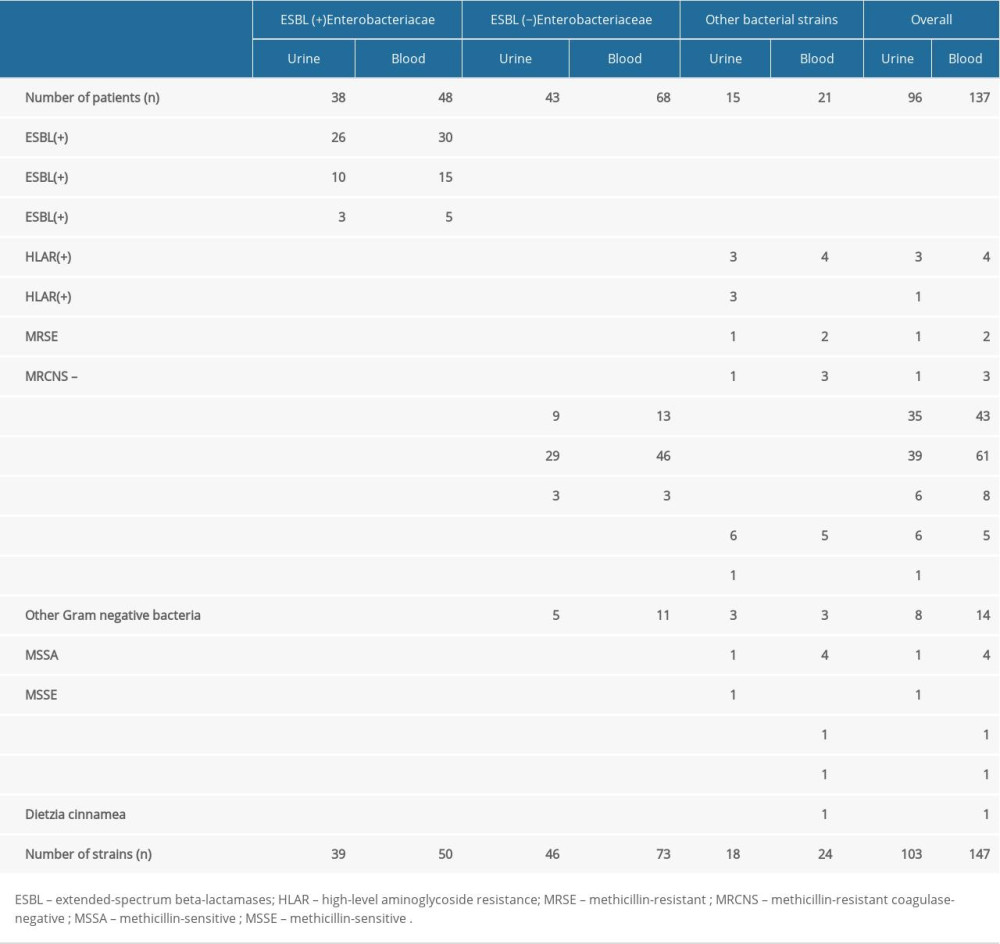

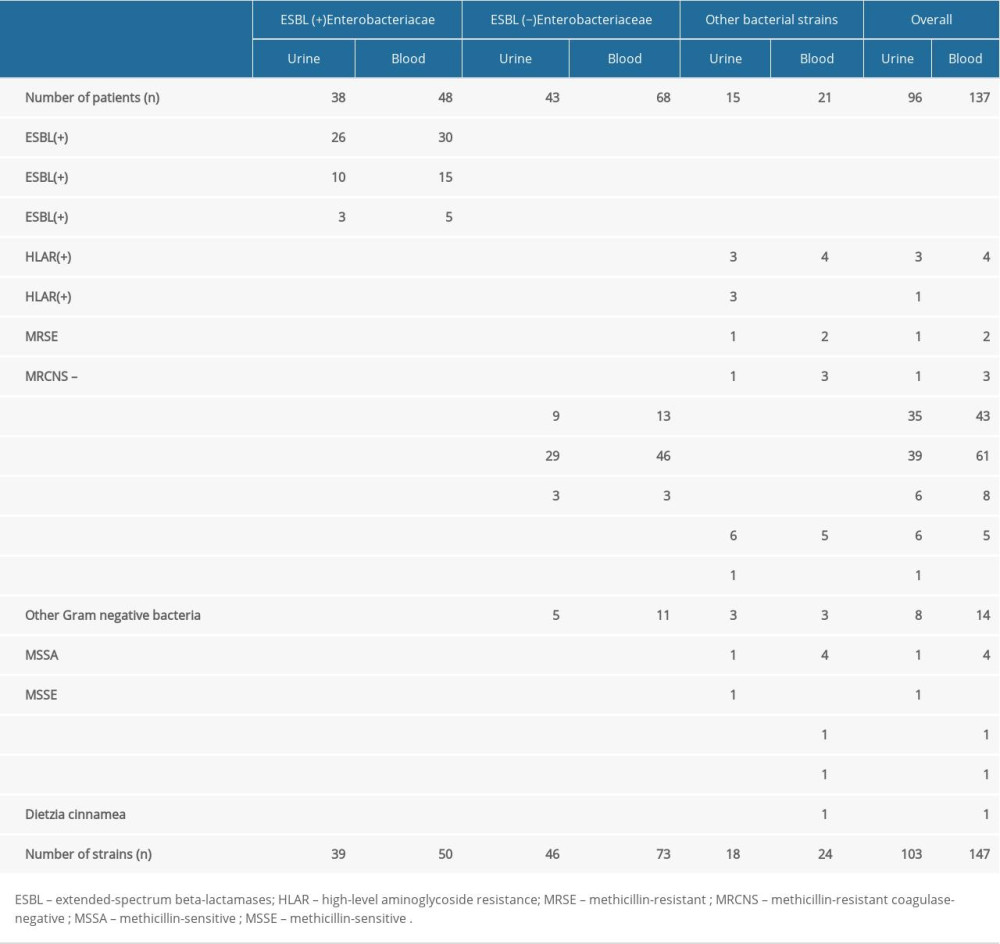

Urine samples obtained from 96 of 137 (70.1%) patients showed significant bacteriuria. In 38 of 96 (39.6%) patients, ESBL-producing representatives of Enterobacteriaceae were cultured, while non-ESBL-producing strains were found in 43 of 96 (44.8%) patients. In 15 of 96 (15.6%) patients, isolates other than Enterobacteriaceae were cultured. About 30% of negative urine culture results raise doubts of the occurrence of a UTI. This is due to a number of limitations related to the collection of urine cultures under acute conditions. Patients often pass urine for the culture incorrectly (too little urine, lack of proper preparation for the collection, anuria). Detailed data on the etiologic agents causing UTI (urine cultures) are presented in Table 1.

In all, 137 analyzed patients’ blood cultures demonstrated positive results. In 116 of 137 (84.7%) patients, blood cultures showed Enterobacteriaceae growth. Strains of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae were shown in 48 of 116 (41.4%) patients, while non-ESBL-producing strains were found in 68 of 116 (58.6%) patients. In 21 of 137 (15.3%) patients, strains other than Enterobacteriaceae were found (Table 1).

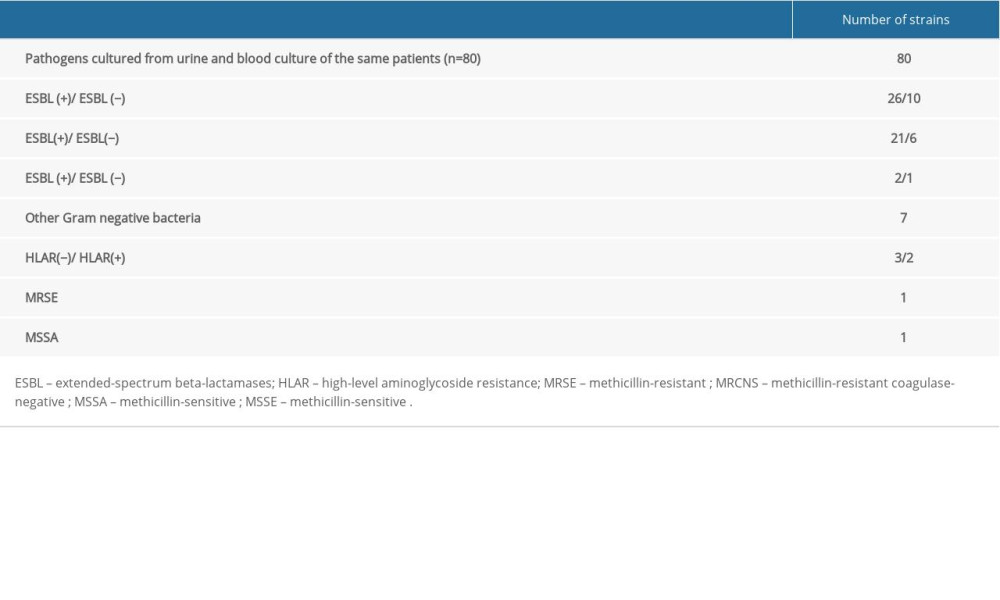

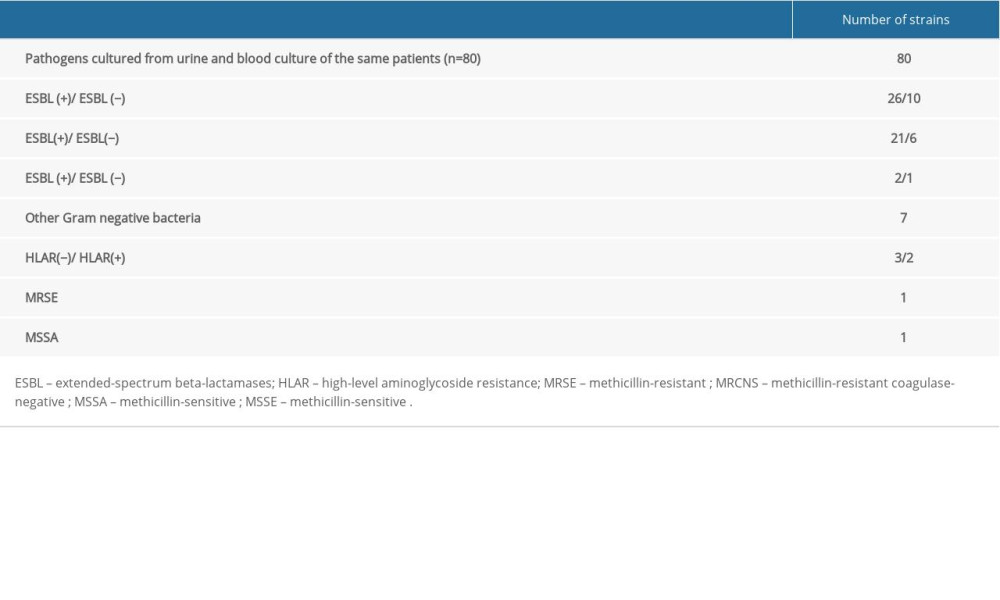

In 83.3% (80/96) of the patients, the pathogens cultured from urine were identical to that cultured in the blood and were most frequently E. coli (26), K. pneumoniae ESBL-positive (21), and E. coli ESBL-positive (10). Detailed data on identical strains cultured in the blood and urine simultaneously are presented in Table 2. In urine, ESBL-positive strains were cultured in 38 patients; in most of these patients, 86.8% (33/38), ESBL-positive strains were also cultured from the blood. Interestingly, 5 of these patients demonstrated positive urine cultures with ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae strains, and this resistance mechanism was not observed in blood isolates. In the urine of 43 patients, ESBL-negative strains were cultured, and in 90.7% (39/43) of these patients ESBL-negative strains were also cultured from the blood. In 1 of 43 patients with positive urine cultures that were ESBL-negative, the blood sample was cultured as an ESBL-positive gram-negative rod.

OUTCOMES:

After initial data collection, treatment effects for over the 3.5-year study period were compared between patients with sepsis caused by ESBL-positive (35%, 48/137) and ESBL-negative (49.6%, 68/137) gram-negative rods. Significantly higher creatinine values (

Among the 48 patients with urosepsis due to ESBL-producing microorganisms, the median length of hospital stay was 11 days, compared with 9 days for patients with non-ESBL-producing

Discussion

In the analysis of 137 patients with a history of urosepsis, demographic data were described and blood and urine isolates were detailed in laboratory test results on admission. In addition, the most common urological comorbidities were described. We also compared groups of patients with urosepsis caused by ESBL-positive and ESBL-negative strains.

We agree with Singer et al who stated that rapid management of sepsis, including intravenous administration of an appropriate antibiotic, is vital for optimal outcomes. Inadequate antibiotic coverage is identified as an outstanding problem in urosepsis [22]. Usually, initiatory antibiotic therapy should be empiric with a broad antimicrobial spectrum to cover all likely causative bacteria, and should be altered on the basis of obtained culture results [5]. At present, ESBL-positive

The prior colonization with ESBL-producing rods was not analyzed a priori in the present study. Such prior colonization could have affected the selection of antimicrobials in favor of agents that empirically target ESBL-producing microorganisms, which would have shortened the median time to receipt of appropriate antimicrobials in the ESBL-positive urosepsis group. This is because clinicians often tailor empiric antimicrobial selection on the basis of previous microbial colonization [37,38]. Early detection of infections, including bacteremia, caused by ESBL-producing microorganisms appears to be of fundamental importance in the treatment of these patients. Future studies should consider prior colonization as a study variable. In conditions of escalating prevalence of ESBL-producing

This study had several limitations. First, it was limited as a single-center analysis and could be improved through subsequent prospective investigations. In addition, our study focused on urological patients in the period of 2017 to 2020; thus, the study group was small and requires confirmation in a wider range of patients during a longer observation time. Given that our study was retrospective, the possibility of incomplete data for patient comorbidities and former medical history, including antibiotic intake history, was relatively high. Further cohort studies on a larger group of patients should be performed. The prior colonization with ESBL-producing microorganisms was not analyzed a priori in the current study. In future studies, it would be worth considering the above and distinguishing the groups of patients, including prior colonization, to choose appropriate treatment.

Conclusions

This study described a 35% prevalence of ESBL-producing

References

1. Foxman B, Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: Incidence, morbidity, and economic costs: Dis Mon, 2003; 49(2); 53-70

2. Bermingham S, Ashe J, Systematic review of the impact of urinary tract infections on health-related quality of life: Br J Urol Int, 2012; 110; 830-36

3. European Association of Urology: European Association of Urology Guidelines 2020 edition, 2020

4. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012: Crit Care Med, 2013; 41; 580-637

5. Bonkat G, Cai T, Veeratterapillay R, Management of Urosepsis in 2018: Eur Urol Focus, 2019; 5(1); 5-9

6. Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000: N Engl J Med, 2003; 348; 1546-54

7. Wagenlehner FME, Weidner W, Naber KG, Optimal management of urosepsis from the urological perspective: Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2007; 30; 390-97

8. Levy MM, Artigas A, Phillips GS, Outcomes of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign in intensive care units in the USA and Europe: A prospective cohort study: Lancet Infect Dis, 2012; 12; 919-24

9. Gupta K, Hooten T, Naber K, International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: Clin Infect Dis, 2011; 52; 103

10. Pitout JD: Drugs, 2010; 70; 313

11. Turner PJ, Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases clinical infectious diseases: Clin Infect Dis, 2005; 41(Suppl 4); S273-75

12. Castanheira M, Simner PJ, Bradford PA, Extended-spectrum b-lactamases: An update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection: JAC Antimicrob Resist, 2021; 3(3); dlab092

13. Perez F, Endimiani A, Hujer KM, The continuing challenge of ESBLs: Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2007; 7; 459-69

14. Peirano G, Pitout JD: Drugs, 2019; 79; 1529-41

15. Cek M, Tandogdu Z, Wagenlehner F, Healthcare-associated urinary tract infections in hospitalized urological patients – a global perspective: results from the GPIU studies: World J Urol, 2014; 32; 1587-94

16. Angus DC, Linde-Zwarble WT, Lindicker J, Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care: Crit Care Med, 2001; 29; 1303-10

17. Ferrández Quirante O, Grau Cerrato S, Luque Pardos S: Braz J Infect Dis, 2011; 15(4); 370-76

18. Venet F, Monneret G, Advances in the understanding and treatment of sepsis-induced immunosuppression: Nat Rev Nephrol, 2018; 14; 121-37

19. Tandogdu Z, Bartoletti R, Cai T, Antimicrobial resistance in urosepsis: Outcomes from the multinational, multicenter global prevalence of infections in urology (GPIU) study 2003–2013: World J Urol, 2016; 34; 1193-200

20. Lee JC, Lee NY, Lee HC: J Microbiol Immunol Infect, 2012; 45; 127-33

21. Wagenlehnera FME, Tandogdub Z, Bjerklund Johansen TE, An update on classification and management of urosepsis: Curr Opin Urol, 2017; 27(2); 133-37

22. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, The Third International Consensus Definitions for depsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3): JAMA, 2016; 315; 801-10

23. Walkty A, Lagacé-Wiens P, Karlowsky J: DSM Micro Notes, 2016, Winnipeg (MB), Diagnostic Services Manitoba

24. Huang Y-W, Alleyne A, Leung V, Chapman M: Can J Hosp Pharm, 2018; 71(2); 119-27

25. Sheng Y, Zheng WL, Shi QF, Clinical characteristics and prognosis in patients with urosepsis from intensive care unit in Shanghai, China: A retrospective bi-centre study: BMC Anesthesiol, 2021; 21(1); 296

26. Subramanian A, Bhat S, Mookkappan S, Empiric antibiotic and in-vitro susceptibility of urosepsis pathogens: Do they match? The outcome of a study from south India: J Infect Dev Ctries, 2021; 15(9); 1346-50

27. Jacoby GA, Medeiros AA, More extended-spectrum β-lactamases: Antimicrob Agents, 1991; 35(9); 1697-704

28. Ryan J, O’Neill E, McLornan L, Urosepsis and the urologist!: Curr Urol, 2021; 15(1); 39-44

29. Ryan J, McLornan L, O’Neill E, The impact of increasing antimicrobial resistance in the treatment of urosepsis: Ir J Med Sci, 2020; 189(2); 611-15

30. Jiang Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Clinical situations of bacteriology and prognosis in patients with urosepsis: Biomed Res Int, 2019; 2019; 3080827

31. Hawser SP, Bouchillon SK, Hoban DJ, Emergence of high levels of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing gram-negative bacilli in the Asia-Pacific region: Data from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART) Program, 2007: Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2009; 53(8); 3280-84

32. Tumbarello M, Sali M, Trecarichi EM: Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2008; 52(9); 3244-52

33. Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y: J Antimicrob Chemother, 2007; 60(5); 913-20

34. Melzer M, Petersen I: J Infect, 2007; 55(3); 254-59

35. Denis B, Lafaurie M, Donay JL: Int J Infect Dis, 2015; 39; 1-6

36. Leistner R, Bloch A, Sakellariou C: J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2014; 2(2); 107-9

37. Vardakas KZ, Tansarli GS, Rafailidis PI: J Antimicrob Chemother, 2012; 67(12); 2793-803

38. Hoban DJ, Nicolle LE, Hawser S: Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2011; 70(4); 507-11

39. Gazin M, Paasch F, Goossens H: J Clin Microbiol, 2012; 50(4); 1140-46

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of urine and blood cultures isolates in patients with urosepsis.

Table 1. Comparison of urine and blood cultures isolates in patients with urosepsis. Table 2. Identical bacterial etiological agents of infections cultured from blood and urine of the same patient.

Table 2. Identical bacterial etiological agents of infections cultured from blood and urine of the same patient. Table 1. Comparison of urine and blood cultures isolates in patients with urosepsis.

Table 1. Comparison of urine and blood cultures isolates in patients with urosepsis. Table 2. Identical bacterial etiological agents of infections cultured from blood and urine of the same patient.

Table 2. Identical bacterial etiological agents of infections cultured from blood and urine of the same patient. In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Outcomes between Single-Level and Double-Level Corpectomy in Thoracolumbar Reconstruction: A ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943797

21 Mar 2024 : Meta-Analysis

Economic Evaluation of COVID-19 Screening Tests and Surveillance Strategies in Low-Income, Middle-Income, a...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943863

10 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Predicting Acute Cardiovascular Complications in COVID-19: Insights from a Specialized Cardiac Referral Dep...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942612

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Enhanced Surgical Outcomes of Popliteal Cyst Excision: A Retrospective Study Comparing Arthroscopic Debride...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.941102

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952