24 February 2022: Clinical Research

A Remote Questionnaire-Based Study to Compare Alcohol Use in 1030 Final-Year High School Students in Split-Dalmatia County, Croatia Before and During the National Lockdown Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Ivona Vrkić Boban1ABCDEF, Marijan Saraga21ADE*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.935567

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935567

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The COVID-19 pandemic affected drinking behaviors among adolescents. This remote questionnaire-based study aimed to compare alcohol use in 1030 final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC), Croatia before and during the national lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: An online self-reported questionnaire survey was conducted among 1030 final-year high school students (57.96% female; mean age 17.71 years, SD=0.66) in SDC. The data were collected from June 6 to July 20, 2020 and from October 12 to December 28, 2020. Differences in drinking habits between groups were detected with the chi-squared (χ²) test and before and during the COVID-19 lockdown using the Z test.

RESULTS: Before the lockdown, 84.66% of students were consuming alcohol, most frequently with friends (78.64%) and “to feel better” (29.51%), while during the lockdown, 44.76% of them were drinking, most frequently with friends (34.37%) and due to boredom (17.48%). Drinking alone (P=0.005) and with family members (P=0.003) significantly increased during the lockdown. No difference in drinking between girls and boys was found before the lockdown, but boys were drinking more during the lockdown (P<0.001). There was no difference in drinking prevalence in different schools before the lockdown, but during the lockdown, more students from vocational schools were drinking (P<0.001) and with higher frequency (P=0.002). Among 53.98% of students during the lockdown, a reduction in frequency of drinking was found (P<0.001), most significantly on islands (P=0.05).

CONCLUSIONS: During the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, alcohol consumption by final-year high school students in SDC significantly decreased, particularly in girls and in gymnasium/private school students.

Keywords: Adolescent, Alcohol Drinking, COVID-19, Boredom, COVID-19, Croatia, Female, Humans, Male, Pandemics, Prevalence, Quarantine, Risk Factors, SARS-CoV-2, Schools, self report, Students

Background

In December 2019, the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus was discovered in Wuhan, China [1]. In the next few months, it spread worldwide and by the end of August 2021, 217 558 771 people had been infected and 4 517 240 people had died [2]. On March 11, 2020, the WHO declared the COVID-19 pandemic [WHO, 2020], which resulted in various kinds of restrictive measures in many countries around the world to prevent further spread of the infection. The Croatian government established a national lockdown from March 19 to May 10, 2020. During that period, all cultural, religious, and sports events were prohibited, as well as gatherings of more than 5 people in one place, restriction of close personal contact, closure of all shops (except grocery stores and pharmacies), schools, and public transport. Such a sudden and dramatic change in everyday activities had a significant impact on physical [3] and mental health [4].

Adolescence is an especially sensitive period, often characterized as a period of storm and stress [5]. Restriction and prohibition of social contact with friends, attending school online, fear of unknown and severe illness of COVID-19, and change in everyday circumstances and activities can affect the mental health of adolescents. Some studies have proved this, showing higher rates of anxiety, depression, and stress due to the pandemic [6,7]. During the lockdown, many adolescents were feeling sad and lonely and experienced sleeping difficulties and problems related to school closures [8]. School closures can have a negative impact on students, especially for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and mental health issues [9]. Isolation in an abusive home could result in increased rates of child abuse, neglect, and exploitation [9]. Excessive screen time, smart phone use, internet addiction, alcohol consumption, COVID-19-related worries, online learning difficulties, and increased conflict with parents negatively affect their mental health [6,8]. Adolescents’ greatest concerns in the COVID-19 crisis were about the disruption of their social interactions and activities, while concerns about infection were very low [10]. A significant increase in depressive symptoms and anxiety and a decrease in life satisfaction during the pandemic were especially found among girls [7,10]. These factors are associated with higher risk for suicidal behavior [11]. Children and adolescents are more likely to experience high rates of anxiety and depression during and after the pandemic [12], so it is important to realize that, compared to adults, the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased long-term adverse consequences on adolescent mental health [12].

In some countries, social media promoted alcohol use, and online misinformation on its protective effects during the pandemic was also reported [13]. Some nations banned alcohol sales during the lockdown, while others declared it an essential commodity [13]. In Croatia, it was possible to buy alcohol beverages in grocery stores for everyone older than 18 years, the same as before the pandemic. Purchases in clubs and cafe bars were impossible because they were closed.

Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among adults were different in many countries during the lockdown [13–22]. Some studies found significantly more drinking among young adults during the lockdown [19,20], while others reported a significantly greater decrease among this population compared to older adults [21,22]. Having at least 1 child younger than age 18 years, having more children at home, depression, less social connectedness, income loss or higher income, living alone, younger age, being a non-healthcare worker, and being technically unemployed increased the risk for drinking during the pandemic [16,17,23]. Boredom, loneliness, and loss of daily structure and conviviality were some reasons for drinking during the lockdown [17]. Online socializing, drinking, and drinking with a child present increased during the lockdown [23].

It was found that the perceived availability of alcohol among adolescents dramatically declined during the pandemic [24]. On the other hand, some parents began to allow their teenagers to drink during family meals or special occasions with them during the lockdown [25]. A few studies found an increase in frequency of alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents [6,20,26]; others reported a significant decrease [7,27–32]; while some found no difference in drinking among adolescents before and during the pandemic [33,34]. Alcohol-related emergencies increased during the lockdown [13], while acute alcohol intoxication among adolescents decreased [35].

In Croatia, the number of adults who were not drinking and those who drank more than 7 drinks a week during the lockdown significantly increased [26]. We could not find any previously published study on alcohol consumption among Croatian adolescents, so the aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence and patterns of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC), Croatia and to compare it with the pre-pandemic period.

Therefore, this remote questionnaire-based study aimed to compare alcohol use in 1030 final-year high school students in SDC before versus during the national lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and Methods

ETHICS APPROVAL:

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, University of Split on June 5, 2020 (Class: 003-08/20-03/0005; File No: 2181-198-03-04-20-0069) and all study procedures we performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 as revised in 2013. Participating in the questionnaire survey was voluntary, and the first page of the questionnaire contained information on study goals and the questionnaire itself and ended with a statement that participating in the survey was considered to indicate informed consent to participate in the study. Participant confidentiality and anonymity were ensured by the fact that only the authors had access to the survey data and the participants never gave their names. The anonymity of the respondents who wanted to participate in the prize drawing was ensured by their individual secret password which they had to provide at the end of the questionnaire.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS:

SDC is situated in the central-southern part of Croatia. It has a population of 454 798 inhabitants [37]. In Croatia, students start high school when they complete 8 years of primary school, generally at age of 14 or 15. The duration of high school education is 3 to 4 years, depending on the school type and program. There are 49 high schools in the county. Most (33) are located in Split and nearby seaside towns and 16 are in rural parts of the county and on islands. There are 9 gymnasiums, 29 vocational, and 11 mixed schools (with both gymnasium and vocational programs). Among them, there are 5 private schools and 2 public law schools. A total of 4347 final-year high students (3rd or 4th grade, depending on the duration of the school programs in different schools) attended these schools in the year 2020/2021. An online link for the questionnaire survey was sent to school principals and/or pedagogues of all 49 high schools and they forwarded it to all students who attended the final year of their high school education in their schools. A total of 1263 students completed the survey (response rate 29.05%). Exclusion criteria were age <16 or >20 years, invalid answers (eg, age 1000 years, graveyard, and drug school), incoherent response pattern, and living outside SDC. The inclusion criteria were students in the last year of their high school education, aged 16 to 20 years, who attended high schools in SDC, agreed to participate in the study, and gave valid and coherent answers. After we excluded 233 of the respondents for not fulfilling the inclusion criteria, we included 1030 participants. To detect differences in drinking habits according to the school type, we divided them into 2 groups: (1) gymnasiums/private schools (includes students who attend gymnasiums, students from mixed schools who attend gymnasium programs, private and public law schools) and (2) vocational schools (including students from vocational schools and those who attend vocational programs in mixed schools). To detect differences according to school location, participants were divided into 3 groups: (1) Split and nearby seaside towns, (2) rural areas (>30 km distance from the seaside), and (3) islands.

METHODS:

Because of the epidemiological situation with the COVID-19 pandemic, our study was performed online. A questionnaire survey about alcohol consumption before and during the lockdown was sent online to all final-year high school students in all of the 49 high schools in SDC. The data were collected in 2 waves: from June 6 to July 20, 2020 and from October 12 to December 28, 2020. Before the study started, we sent an informative letter and contacted by phone and email school principals and/or school psychologists/pedagogues in all 49 high schools in SDC. We informed them about the study, including the aim and methods. After they gave us their consent, we sent them an online link which they had to forward to all of their final-year high school students to take the survey. Participants were able to access the online link in school websites, virtual classrooms, or other network groups (smartphone messaging applications). There was an informative letter at the top of the survey describing the aim and methods of the study. Access to the survey was voluntary and after reading the informative letter, starting to take the survey was considered as a providing consent for study participation. Students were only able to take the survey 1 time. To achieve a greater response and to make our results more representative and realistic, we rewarded 1 randomly chosen participant with 1000 Croatian kunas (HRK). The survey was anonymous, so the students who wanted to participate in the prize drawing had to enter a secret password at the end of the survey.

STUDY QUESTIONNAIRE:

We used

Drinking habits before the lockdown period were assessed with the following questions: 1.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

We used SPSS 25 (IBM, Armonk, New York; 2017) statistics software for statistical analyses. The study size was determined using a calculator for defining the study sample size with a power of 95%. Data are presented in tables and graphs. Numeric variables are shown with mean and standard deviation. The normality of distribution was previously tested by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The prevalence of defined drinking habits such as frequency, reasons, and social context of alcohol consumption are presented with absolute and percentage values. We used the χ2 test to detect differences in examined variables between groups. We used the χ2 test to detect possible associations between school type and location with changes in drinking habits during the lockdown to explore if there were any differences in drinking habits during the lockdown between gymnasium/private and vocational school students. The differences in changes of drinking habits during the lockdown between students in Split and surrounding areas, rural areas, and islands were detected with the same method. The differences in frequency of meeting with friends according to the school type, location, and gender were also examined. The frequency of meeting with friends was scored on a scale from 0 to 5, where the value 0 indicated “no meeting at all” and 5 indicated “meeting every day”. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to detect differences in frequency of meeting with friends according to the location (an independent category variable). The difference in socializing with friends according to the school type and gender was detected with the Mann-Whitney U test. The conclusion about detected differences was made on the basis of cumulative values using cumulative percentage series “more than”, where a higher value indicates more frequent socializing. The Z test of differences in proportions of 2 independent variables was used to detect difference in drinking habits (frequency, reasons, and social context of drinking) before and during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY PARTICIPANTS:

Among the 1030 respondents who met the inclusion criteria, there were 433 (42.04%) boys and 597 (57.96%) girls. The mean age was 17.71±0.66 years. There were 425 (41.26%) students attending gymnasiums/private schools and 605 (58.74%) attending vocational schools in SDC; 826 students (80.19%) attended schools in Split and nearby seaside towns, while 204 (19.81%) attended schools on islands and rural parts of the SDC, 155 (15.05%) of them in rural areas and 49 (4.76%) on islands.

CHARACTERISTICS OF ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION AMONG FINAL-YEAR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS IN SDC DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC LOCKDOWN:

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, 269 (26.12%) of our respondents did not meet with their friends. On the other hand, 177 (17.18%) of them were meeting with their friends every day and 108 (10.49%) of them met with friends 3–6 times a week (

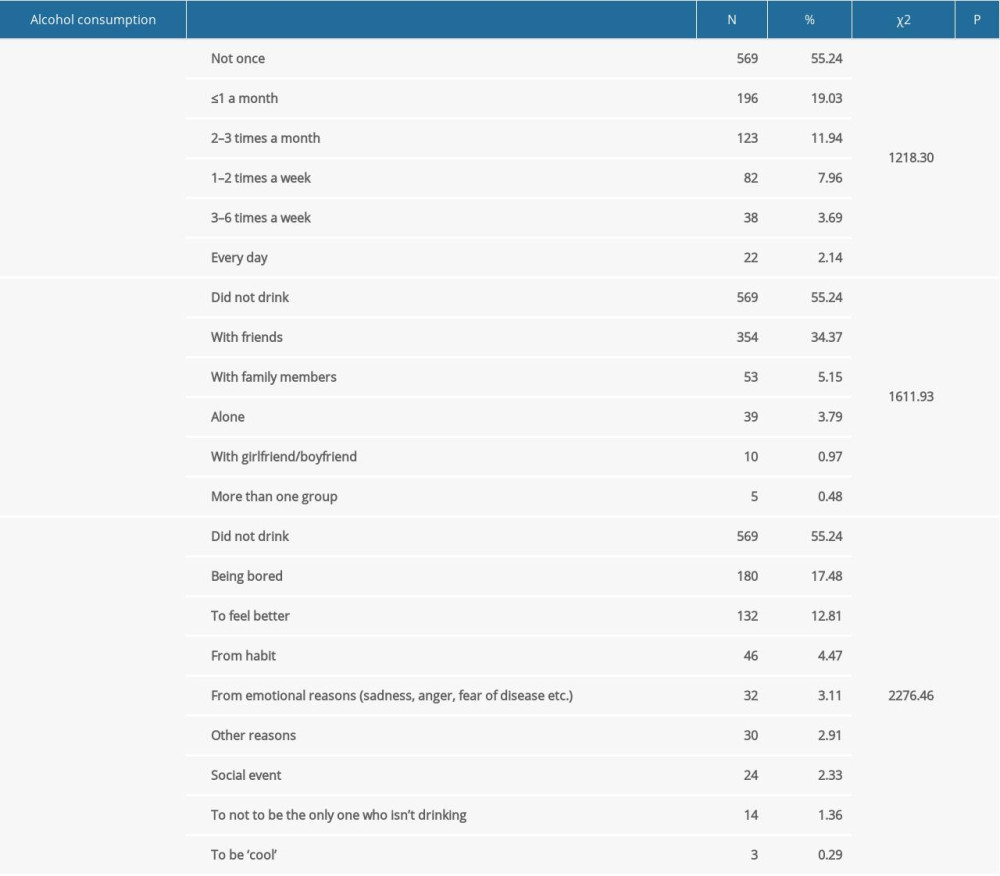

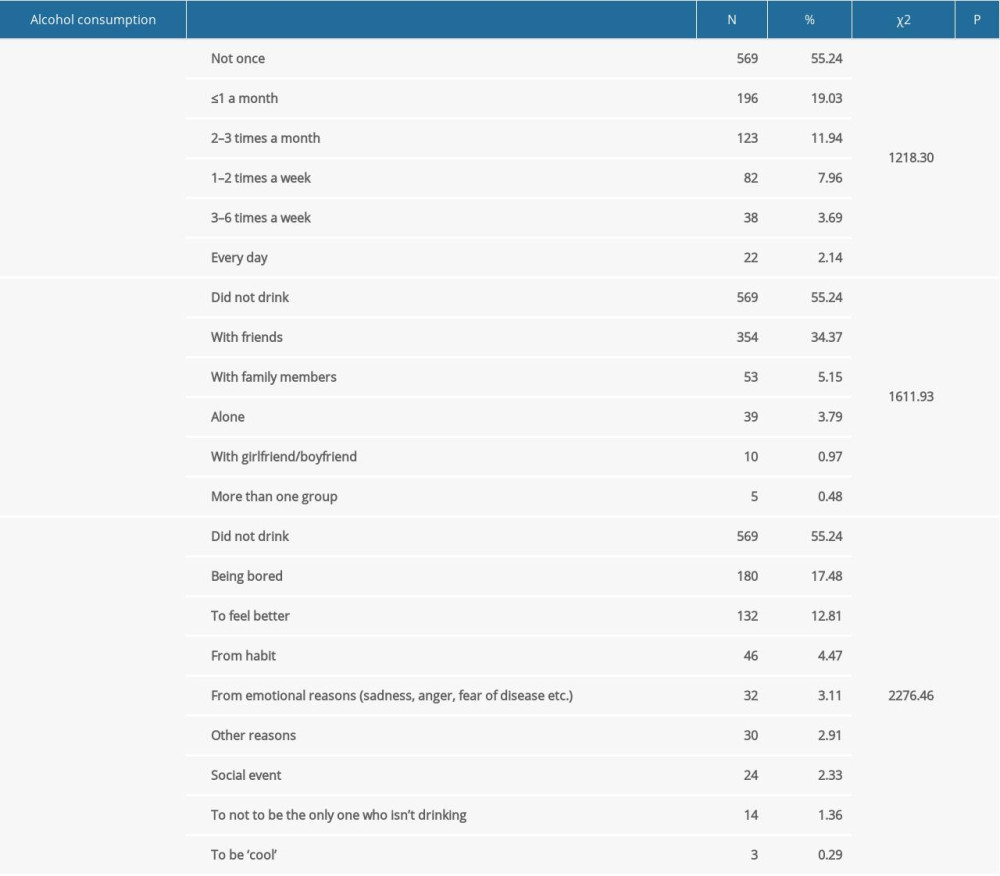

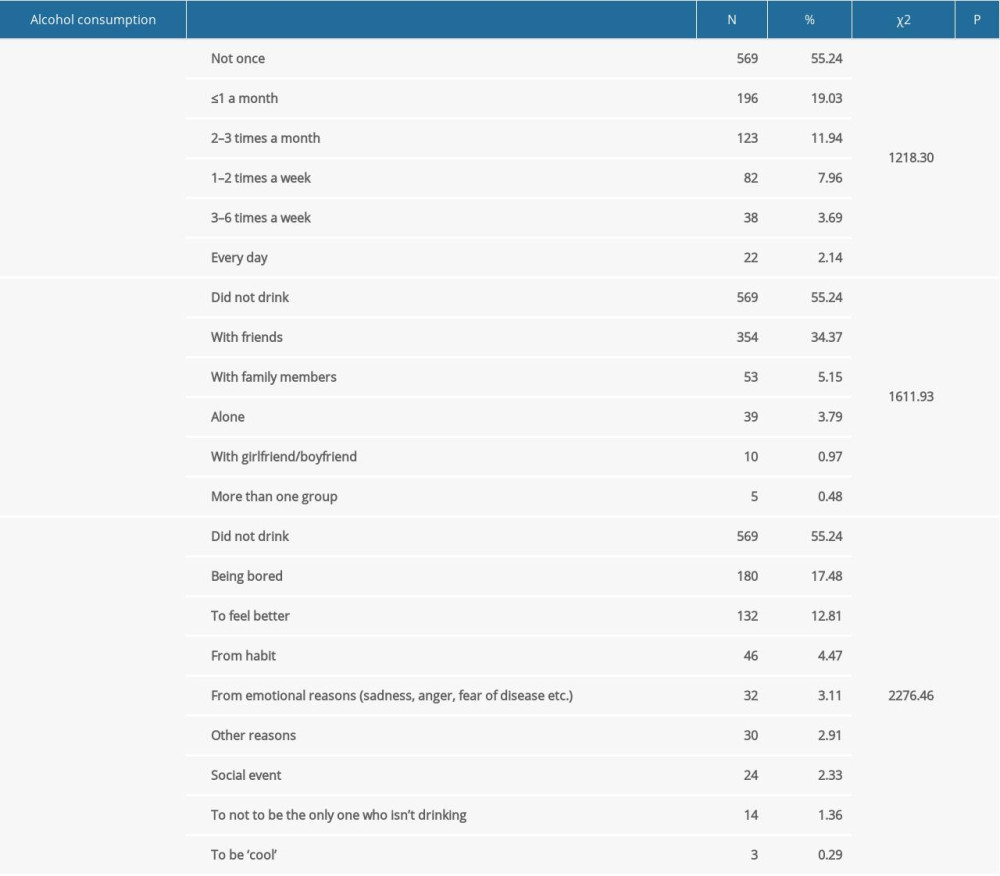

The majority of students (55.24%) did not consume alcohol at all during the lockdown, while 22 (2.14%) students were drinking alcohol every day (P<0.001) (Table 1). Students who consumed alcohol most frequently did it with their friends (34.37%) and because they were bored (17.48%). More details about frequency, social context, and reasons for drinking during the COVID-19 lockdown are shown in Table 1.

DIFFERENCES IN ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION AMONG FINAL-YEAR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS IN SDC BEFORE AND DURING THE NATIONAL COVID-19 PANDEMIC LOCKDOWN:

Before the lockdown, 84.66% of students were consuming alcohol, while during the lockdown, 44.76% of them were drinking (

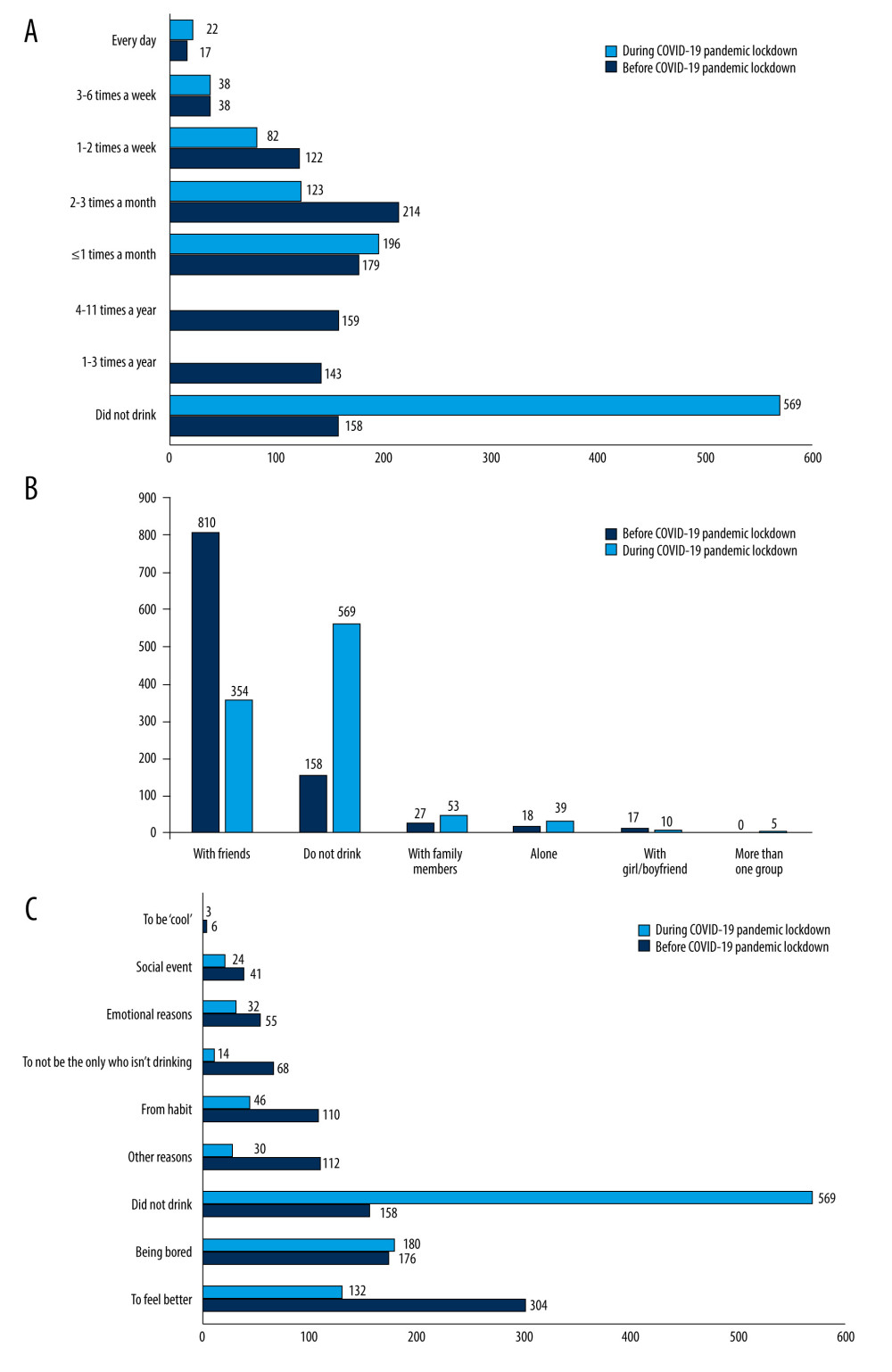

Before the lockdown, alcohol was most commonly consumed 2–3 times a month, while during the lockdown it was consumed ≤1 time a month (P<0.001). Figure 1A shows more details about frequency of alcohol consumption before and during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

Drinking with friends significantly decreased during the lockdown (from 78.64% to 34.37%; P<0.001). On the other hand, there was a significant increase in alcohol consumption with family members (from 2.62% to 5.15%; P=0.003), alone (from 1.75% to 3.79%; P=0.005), and with more than 1 group (alone and with friends or alone with family members; from 0.00% to 0.48%; P=0.025), as shown in Figure 1B. There was no significant difference in drinking with girlfriend/boyfriend before and during the lockdown (P=0.175).

The most common reason for drinking before the lockdown was „to feel better” (29.51%). During the lockdown, the most common reason was „being bored” (17.48%). There was a significant decrease in most of the reasons for drinking: “to feel better” (P<0.001), “not to be the only one who isn’t drinking (P<0.001), from habit (P<0.001), for emotional reasons (P=0.006), social event (P=0.0161), “to be cool” (P<0.001), and other reasons (P<0.001), but we found no difference in drinking due to boredom before and during the lockdown (P=0.408). Figure 1C shows the distribution of reasons for drinking among participants of the study in absolute numbers before and during the pandemic.

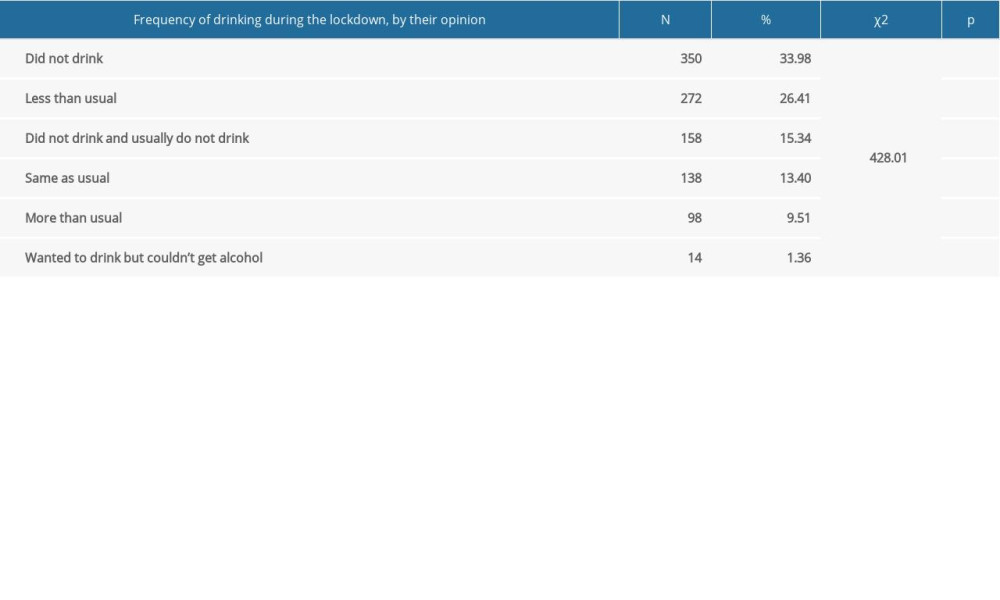

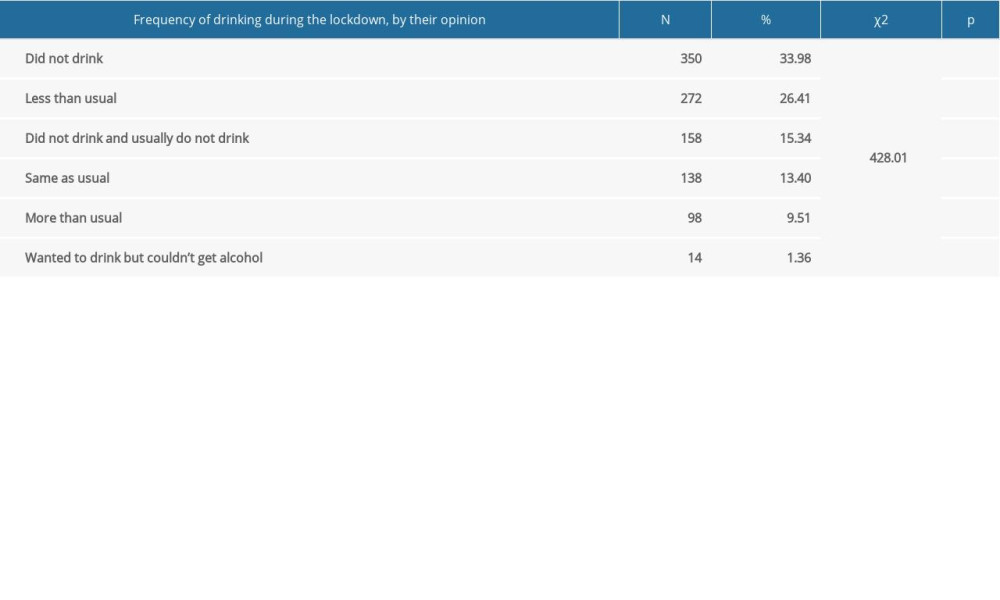

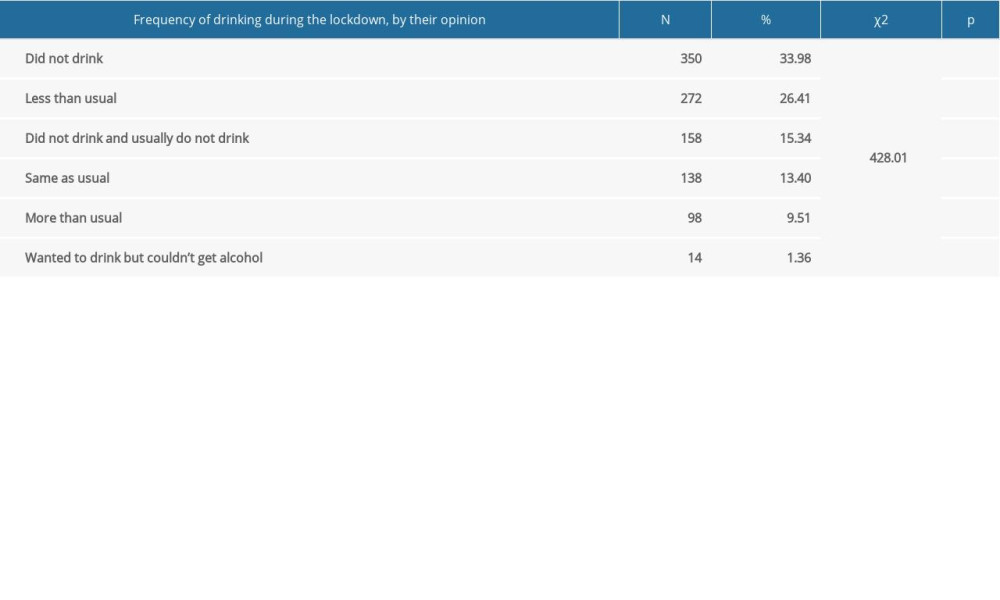

Among 53.98% of students, the frequency of drinking significantly decreased during the lockdown (

Students indicated they believed that alcohol consumption significantly decreased during the lockdown (P<0.001). Among students who used to drink before, 33.98% did not drink at all during the lockdown and 26.41% were drinking less than usual (Table 2).

DIFFERENCES IN ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION BEFORE AND DURING THE LOCKDOWN AMONG FINAL-YEAR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS IN SDC ACCORDING TO SCHOOL TYPE AND LOCATION:

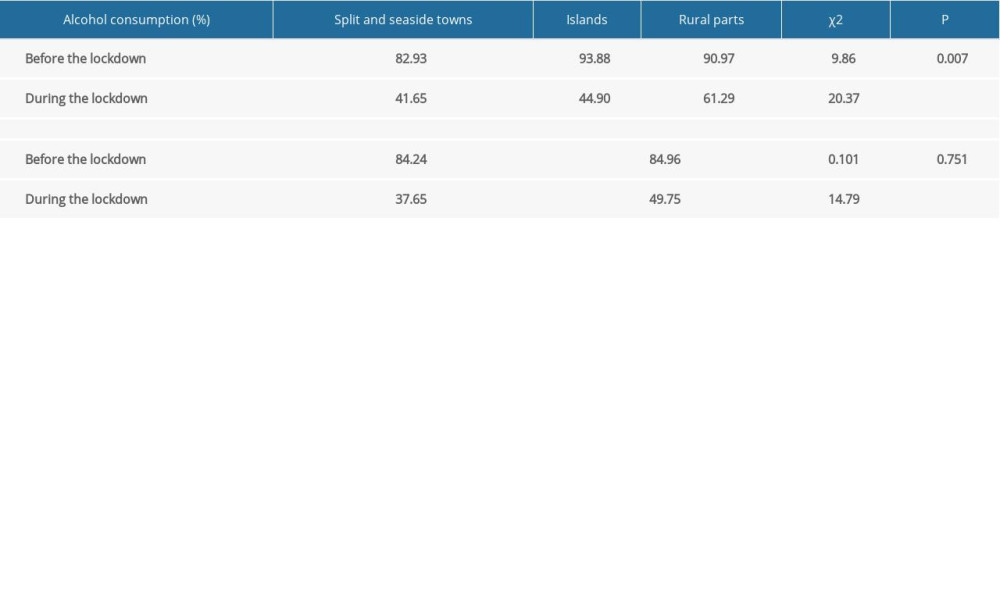

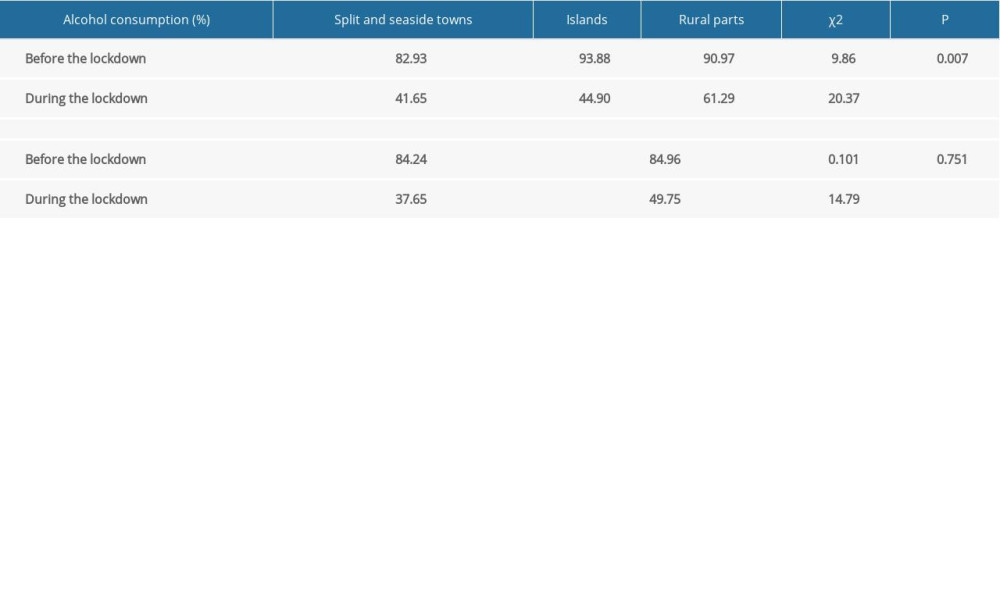

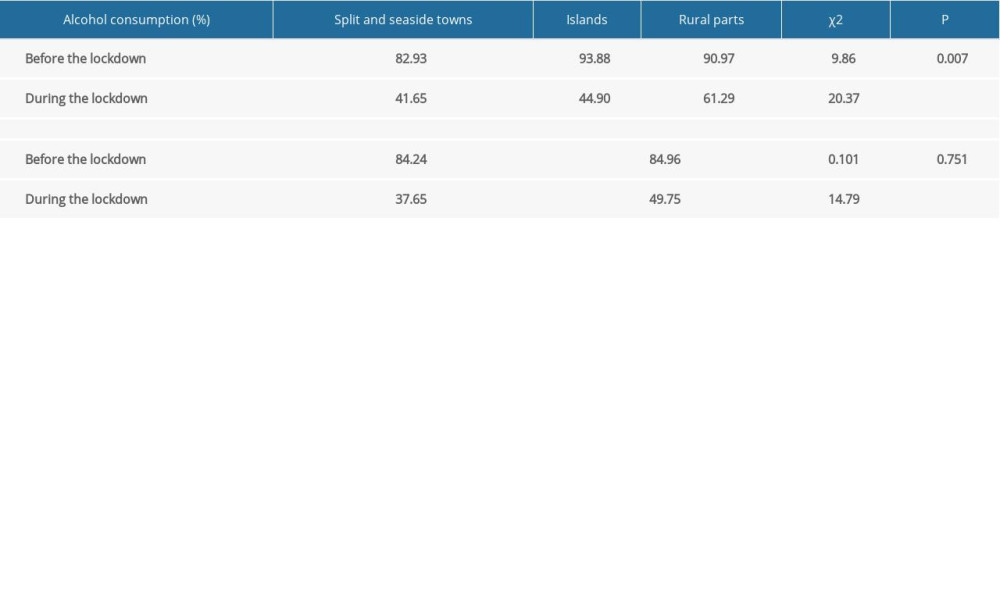

Before the lockdown, alcohol was most frequently consumed on islands (P=0.007), while during the lockdown, consumption was the highest in rural areas (P<0.001). Before the lockdown, there was no significant difference in drinking among students in gymnasiums/private schools and vocational schools (P=0.751), while during the lockdown, alcohol consumption was higher in vocational schools (P<0.001). Table 3 shows more details of alcohol consumption according to the school type and location.

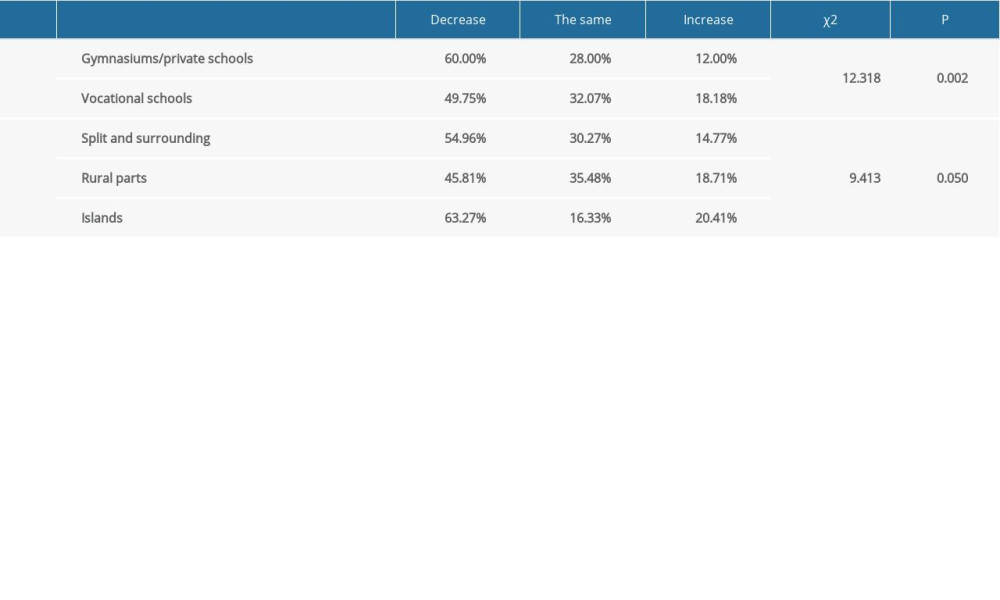

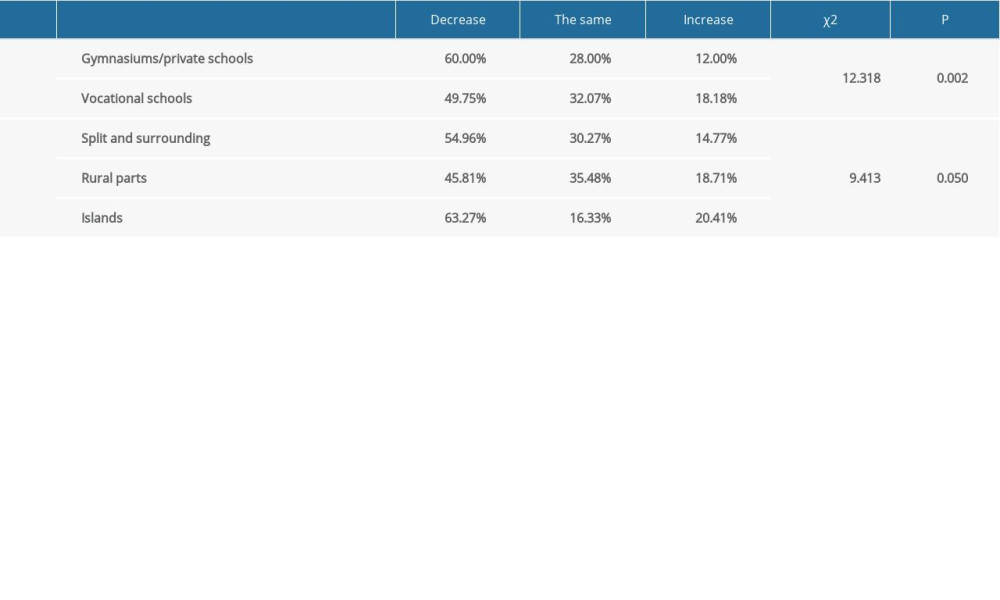

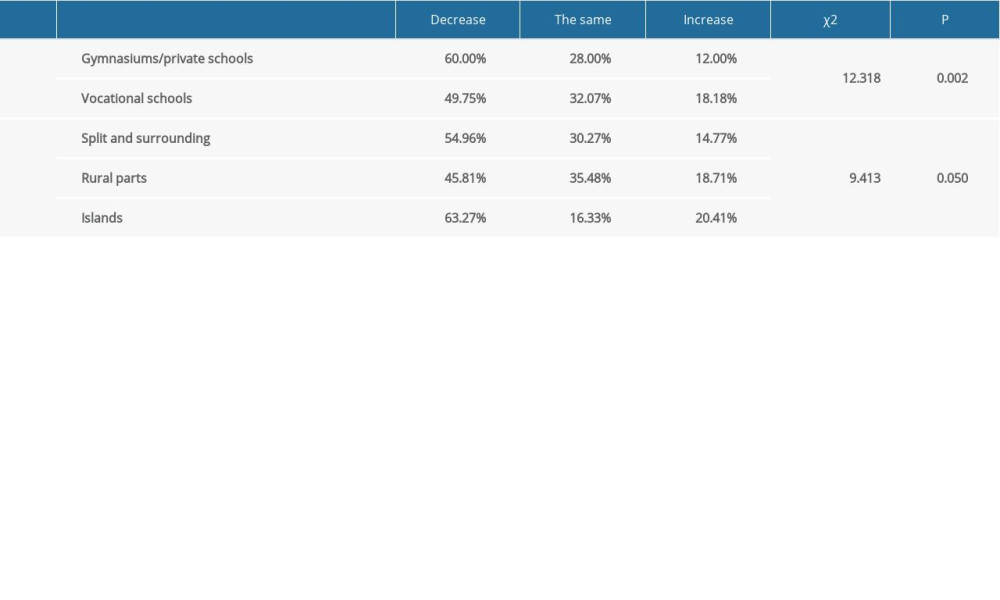

There was significantly greater reduction in drinking frequency during the lockdown among students in gymnasiums/private schools than in vocational schools (P=0.002) and among those who were attending schools on islands (P=0.050). The most significant increase was found among students on islands and in vocational schools (Table 4).

FREQUENCY OF SOCIALIZING WITH FRIENDS DURING THE LOCKDOWN:

Students attending vocational schools met with their friends significantly more frequently during the lockdown than did students in gymnasiums/private schools (Z=7.52; P<0.001), as well as students from rural parts compared to those in Split and on islands (H=10.84; P=0.044). Boys also socialized with friends significantly more during the lockdown compared to girls (Z=20.39; P<0.001) (Table 5).

Discussion

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY:

Our study design may have caused some bias because it was an online self-reported questionnaire. The link was sent online to all students, but only those who were willing to participate in the study and wanted to complete the entire survey questionnaire were included, so the results possibly do not represent the general population. However, we had a large sample of 1030 respondents (approximately 24% of all final-year high school students in SDC), and all invalid and incoherent answers were excluded from the study. The questionnaire was self-reported, so we had to rely on the sincerity of the participants’ answers. Due to the epidemiological situation, an online survey was the only option. The data on alcohol consumption before and during the lockdown were collected at the same time and after the lockdown (from June to July 2020 and October to December 2020, while the lockdown lasted from March to May 2020), so we had to rely on students’ memory of their behaviors during that time. Also, the lockdown lasted only 1.5 months. Still, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to include all schools in SDC and to explore differences between drinking behaviors among adolescents according to the school type and location. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first study of alcohol consumption among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Croatia. Due to the large number of participants and the fact that the study covered a wide area, as well as the fact that the restrictive measures were the same in all parts of the country, we can possibly generalize these results to all Croatian adolescents, but further studies are needed.

Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, alcohol consumption by final-year high school students in SDC significantly decreased, particularly in girls and in gymnasium/private school students.

Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown from March 19 to May 10, 2020 (N=1030). Table 2. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC)during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period from March 19 to May 10, 2020, compared to a period before the lockdown, according to their own opinion (N=1030).

Table 2. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC)during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period from March 19 to May 10, 2020, compared to a period before the lockdown, according to their own opinion (N=1030). Table 3. Prevalence of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) before and during the national COVID-19 lockdown period (from March 19 to May 10,2020), according to location and type of school attended (N=1030).

Table 3. Prevalence of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) before and during the national COVID-19 lockdown period (from March 19 to May 10,2020), according to location and type of school attended (N=1030). Table 4. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (from March 19 to May 10, 2020) compared to before the lockdown, according to the school type and location (N=1030).

Table 4. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (from March 19 to May 10, 2020) compared to before the lockdown, according to the school type and location (N=1030).

References

1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019: N Engl J Med, 2020; 382(8); 727-33

2. WHO: WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard | WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard with vaccination data

3. Flanagan EW, Beyl RA, Fearnbach SN, The impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on health behaviors in adults: Obesity (Silver Spring), 2021; 29(2); 438-45

4. Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis: J Affect Disord, 2021; 281; 91-98

5. Casey BJ, Jones RM, Levita L, The storm and stress of adolescence: Insights from human imaging and mouse genetics: Dev Psychobiol, 2010; 52(3); 225-35

6. Jones EAK, Mitra AK, Bhuiyan AR, Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review: Int J Environ Public Health, 2021; 18(5); 2470

7. Thorisdottir IE, Asgeirsdottir BB, Kristjansson AL, Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: A longitudinal, population-based study: Lancet Psychiatry, 2021; 8(8); 663-72

8. Szwarcwald CL, Malta DC, Barros MbdA, Associations of sociodemographic factors and health behaviors with the emotional well-being of adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(11); 6160

9. Lee J, Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19: Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2020; 4(6); 421

10. Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: J Youth Adolesc, 2021; 50; 44-57

11. Hermosillo-de-la-Torre AE, Arteaga-de-Luna SM, Acevedo-Rojas DL, Psychosocial correlates of suicidal behavior among adolescents under confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Aguascalientes, Mexico: A cross-sectional population survey: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(9); 4977

12. Meherali S, Punjani N, Louie-Poon S, Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: A rapid systematic review: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(7); 3432

13. Murthy P, Narasimha VL, Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on alcohol use disorders and complications: Curr Opin Psychiatry, 2021; 34(4); 376-85

14. Chodkiewicz J, Talarowska M, Miniszewska J, Alcohol consumption reported during the COVID-19 pandemic: The initial stage: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020; 17; 4677

15. Kilian C, Rehm J, Allebeck P, Alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: A large-scale cross-sectional study in 21 countries: Addiction, 2021; 116(12); 3369-80

16. Wardell JF, Kempe T, Rapinda KK, Drinking to cope during COVID-19 pandemic: The role of external and internal factors in coping motive pathways to alcohol use, solitary drinking, and alcohol problems: Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2020; 44; 2073-83

17. Vanderbruggen N, Matthys F, Van Laere S, Self-reported alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use during COVID-19 lockdown measures: Results from a Web-Based Survey: Eur Addict Res, 2020; 26(6); 309-15

18. Ferrante G, Camussi E, Piccinelli C, Did social isolation during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic have an impact on the lifestyles of citizens?: Epidemiol Prev, 2020; 44(5–6 Suppl 2); 353-62

19. Jacob L, Smith L, Armstrong NC, Alcohol use and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study in a sample of UK adults: Drug Alcohol Depend, 2021; 219; 108488

20. Guignard R, Andler R, Quatremère G, Changes in smoking and alcohol consumption during COVID-19-related lockdown: A cross-sectional study in France: Eur J Public Health, 2021; 31(5); 1076-83

21. Merlo A, Severeijns NR, Benson S, Mood and changes in alcohol consumption in young adults during COVID-19 lockdown: A model explaining associations with perceived immune fitness and experiencing COVID-19 symptoms: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(19); 10028

22. Villanueva-Blasco VJ, Villanueva Silvestre V, Vázquez-Martínez A, Age and living situation as key factors in understanding changes in alcohol use during COVID-19 confinement: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(21); 11471

23. Garcia-Cerde R, Valente JY, Sohi I, Alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America and the Carribean: Rev Panam Salud Publica, 2021; 45; e52

24. Miech R, Patrick ME, Keyes K, Adolescent drug use before and during U.S. national COVID-19 social distancing policies: Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2021; 226; 108822

25. Maggs JL, Cassinat JR, Kelly BC, Parents who first allowed adolescents to drink alcohol in a family context during spring 2020 COVID-19 emergency shutdowns: J Adolesc Health, 2021; 68(4); 816-18

26. Sen LT, Siste K, Hanafi E, Insights into adolescents’ substance use in a low-middle-income country during the COVID-19 pandemic: Front Psychiatry, 2021; 12; 739698

27. Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM, What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors: J Adolesc Health, 2020; 67(3); 354-61

28. Roges J, Bosque-Prous M, Colom J, Consumption of alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco in a cohort of adolescents before and during COVID-19 confinement: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18; 7849

29. Malta DC, Gomes CS, Barros MBA, The COVID-19 pandemic and changes in the lifestyles of Brazilian adolescents: Rev Bras Epidemiol, 2021; 24; e210012

30. Pelham WE, Tapert SF, Gonzalez MR, Adolescent substance use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal survey in the ABCD study cohort: J Adolesc Health, 2021; 69(3); 390-97

31. Fruehwirth JC, Gorman BL, Perreira KM, The effect of social and stress-related factors on alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: J Adolesc Health, 2021; 69(4); 557-65

32. Clare PJ, Aiken A, Yuen WS, Alcohol use among young Australian adults in May–June 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective cohort study: Addiction, 2021; 116(12); 3398-407

33. Kuitunen I, Social restrictions due to COVID-19 and the incidence of intoxicated patients in pediatric emergency department: Ir J Med Sci, 2021; 1-3 [Online ahead of print]

34. Chaffee BW, Cheng J, Couch ET, Adolescent’s substance use and physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic: JAMA Pediatr, 2021; 175(7); 715-22

35. Pigeaud L, de Veld L, van Hoof J, van der Lely N, Acute alcohol intoxication in dutch adolescents before, during, and after the first COVID-19 lockdown: J Adolesc Health, 2021; 69(6); 905-9

36. Đogaš Z, Lušić Kalcina L, Pavlinac Dodig I, The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle and mood in Croatian general population: A cross-sectional study: Croat Med J, 2020; 61; 309-18

37. Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2011 www.dzs.hr

38. ESPAD Group (2020): ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs, EMCDDA Joint Publications, 2020, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union Available from: ESPAD report 2019 Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs

39. Vrkić Boban I, Vrca A, Saraga M, Changing pattern of acute alcohol intoxications in children: Med Sci Monit, 2018; 24; 5123-31

40. Essau CA, de la Torre-Luque A, Adolescent psychopathological profiles and the outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudional findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study: Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2021; 110; 110330

41. Romano I, Patte KA, de Groh M, Substance-related coping behaviours among youth during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: Addict Behav Rep, 2021; 14; 100392

42. Grigoletto V, Cognigni M, Occhipinti AA, Rebound of severe alcoholic intoxications in adolescents and young adults after COVID-19 lockdown: J Adolesc Health, 2020; 67(5); 727-29

Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown from March 19 to May 10, 2020 (N=1030).

Table 1. Characteristics of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown from March 19 to May 10, 2020 (N=1030). Table 2. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC)during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period from March 19 to May 10, 2020, compared to a period before the lockdown, according to their own opinion (N=1030).

Table 2. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC)during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period from March 19 to May 10, 2020, compared to a period before the lockdown, according to their own opinion (N=1030). Table 3. Prevalence of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) before and during the national COVID-19 lockdown period (from March 19 to May 10,2020), according to location and type of school attended (N=1030).

Table 3. Prevalence of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) before and during the national COVID-19 lockdown period (from March 19 to May 10,2020), according to location and type of school attended (N=1030). Table 4. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (from March 19 to May 10, 2020) compared to before the lockdown, according to the school type and location (N=1030).

Table 4. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (from March 19 to May 10, 2020) compared to before the lockdown, according to the school type and location (N=1030). Table 1. Characteristics of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown from March 19 to May 10, 2020 (N=1030).

Table 1. Characteristics of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown from March 19 to May 10, 2020 (N=1030). Table 2. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC)during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period from March 19 to May 10, 2020, compared to a period before the lockdown, according to their own opinion (N=1030).

Table 2. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC)during the national COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period from March 19 to May 10, 2020, compared to a period before the lockdown, according to their own opinion (N=1030). Table 3. Prevalence of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) before and during the national COVID-19 lockdown period (from March 19 to May 10,2020), according to location and type of school attended (N=1030).

Table 3. Prevalence of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) before and during the national COVID-19 lockdown period (from March 19 to May 10,2020), according to location and type of school attended (N=1030). Table 4. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (from March 19 to May 10, 2020) compared to before the lockdown, according to the school type and location (N=1030).

Table 4. Changes in frequency of alcohol consumption among final-year high school students in Split-Dalmatia County (SDC) during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (from March 19 to May 10, 2020) compared to before the lockdown, according to the school type and location (N=1030). In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Outcomes between Single-Level and Double-Level Corpectomy in Thoracolumbar Reconstruction: A ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943797

21 Mar 2024 : Meta-Analysis

Economic Evaluation of COVID-19 Screening Tests and Surveillance Strategies in Low-Income, Middle-Income, a...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943863

10 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Predicting Acute Cardiovascular Complications in COVID-19: Insights from a Specialized Cardiac Referral Dep...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942612

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Enhanced Surgical Outcomes of Popliteal Cyst Excision: A Retrospective Study Comparing Arthroscopic Debride...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.941102

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952