27 September 2022: Database Analysis

Prevalence of Serious Pathology Among Adults with Low Back Pain Presenting for Chiropractic Care: A Retrospective Chart Review of Integrated Clinics in Hong Kong

Eric Chun-Pu ChuDOI: 10.12659/MSM.938042

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e938042

Abstract

BACKGROUND: There is a limited understanding of the frequency at which chiropractors encounter patients with serious pathology such as malignancy, fracture, and infection. This retrospective study aimed to estimate the prevalence and types of serious pathology among adults with new low back pain presenting to chiropractors in an integrated healthcare organization in Hong Kong, with the hypothesis that such pathology would be found in less than 5% of patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: We identified adults presenting to a chiropractor with new low back pain across 30 clinics with 38 chiropractors, and a subset with previously undiagnosed serious pathology from January 2020 through July 2022. Data were extracted from the electronic medical records, including messaging alerts for serious pathology, notes, radiology reports, and specialist follow-up. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze results.

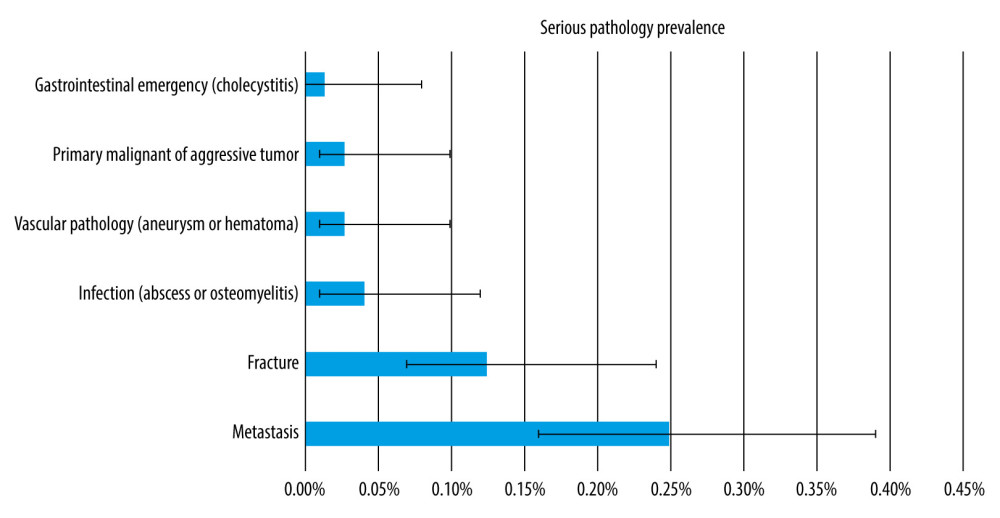

RESULTS: Among the 7221 identified patients with new-onset low back pain (mean age 61.6±14.3), 35 presented with serious pathology. After excluding 54 cases not meeting inclusion criteria, the prevalence of serious pathology (95% CI) was 35/7221 (0.48%; 0.35-0.67%). Individual condition prevalence included metastasis (0.25%; 0.16-0.39%), fracture (0.12%; 0.07-0.24%), infection (0.04%; 0.01-0.12%), vascular pathology (0.03%; 0.01-0.10%), primary tumor (0.03%; 0.01-0.10%), and gastrointestinal emergency (0.01%; 0.00-0.08%).

CONCLUSIONS: This study found that serious pathology was uncommon among adults with new low back pain presenting for chiropractic care in Hong Kong, findings which are most consistent with previous research describing the prevalence of serious pathology among low back pain patients in primary care settings.

Keywords: Chiropractic, Fractures, Bone, infections, Neoplasms, Adult, Aged, Hong Kong, Humans, Low Back Pain, Middle Aged, Prevalence

Background

In the context of low back pain, serious pathology, also called severe or urgent pathology, generally refers to malignancy, fracture, infection, or cauda equina syndrome [1–5]. Previous studies found that less than 5% of patients in the primary care setting presenting with low back pain have serious pathology [1,2]. However, limited research has examined the prevalence of serious pathology in the chiropractic setting [6–9]. Given that chiropractors are healthcare providers that most often manage low back pain [10], an accurate estimate of the prevalence and types of serious pathology that these clinicians encounter is important for avoiding misdiagnosis and maintaining high quality of care.

While the prevalence of patients with low back pain presenting with serious pathology in primary care settings is relatively low [1,2], the prevalence increases in secondary (ie, medical specialist) and tertiary care settings (ie, hospital). For example, malignancy is estimated to account for 0.1% to 0.7% of primary care presentations, yet may account for 1.5% to 7.0% in secondary and tertiary care settings [1]. While chiropractors are not medical primary care physicians, they have been described as primary spine care providers as they act as an initial point of contact for spine and musculoskeletal disorders [11,12], but do not directly treat serious pathology given their scope of practice [13,14]. Accordingly, we suspected that the prevalence of serious pathology presenting to chiropractors would be closest to that of primary care rather than secondary or tertiary care settings.

Previous studies examining serious pathology among patients presenting to chiropractic clinics have been limited to the analysis of plain film radiographic findings, and have not included advanced imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or follow-up testing to confirm the presence of severe pathology [6–9]. Radiographs are not an ideal screening tool for serious pathology [15,16]. For example, at least 50% of bone mineral must be loss for metastasis to be detected, thus potentially yielding a false-negative report [16]. Conversely, radiographs may show abnormalities which are inconclusive and lead to false-positive diagnoses [15,17]. As a result, such previous estimates of the prevalence of serious pathology presenting to chiropractors could be biased.

Surveys have also been used to examine the rate at which chiropractors encounter serious pathology. In a survey from 2012, United States (US) chiropractors reported encountering a previously undiagnosed life-threatening condition once every 2.5 years in practice, which was most often cancer, followed by abdominal aortic aneurysm [18]. In a 2014 survey, US chiropractors reported seeing a patient with fracture, metastasis, spinal infection less than once per year each [19], but no specific prevalence data was given. As these survey studies did not corroborate results with medical records data, they could also be prone to recall bias [20].

Use of radiographs has traditionally been high among chiropractors, in contrast to MRI [15,21]. In 2014 in the US, 47% of chiropractors reported having equipment to take radiographs in their office [19], and while it is not clear what percentage of chiropractors have MRI equipment in their office, the overall routine use of radiographs by chiropractors far outnumbers use of MRI, at 35% versus 1%, respectively [10]. An ideal practice setting to study the prevalence of serious pathology presenting to chiropractors would include advanced imaging equipment, such as MRI, and a shared medical records system. However, only about 5% of chiropractors are integrated into medical settings [19], making this type of research a challenge.

In Hong Kong, the site of the current study, and in the US, chiropractors are portal-of-entry healthcare providers that often manage spinal problems, with low back pain being the most common condition treated [10]. The most common treatment chiropractors utilize is spinal manipulative therapy [10], which is a type of manual therapy directed to the spinal joints [22]. This therapy is contraindicated in cases of serious pathology such as spinal infection, metastasis, and fracture, as it may aggravate these conditions [15,23]. For example, case reports have documented exacerbation of an underlying unrecognized fracture or spinal metastasis with spinal manipulation [24]. Accordingly, chiropractors should be vigilant to detect such cases of serious pathology, which could influence the management strategy and shift the immediate treatments toward medical rather than chiropractic care [25].

As healthcare providers, chiropractors routinely perform history-taking and examination for patients with new concerns of low back pain [19]. This includes a series of questions to screen for red flags, including questions about a history of cancer, trauma, fever or recent infection, progressive or severe neurologic complaints, bowel or bladder dysfunction, and pain that is worse at night [25]. Chiropractors’ examinations for low back pain typically include range of motion, strength, sensation, and reflex assessments [26,27], as well as spinal palpation for pain and mobility [28]. These findings inform the management strategy, including whether to obtain diagnostic imaging and refer to medical specialists [25].

Given the limitations of previous research, this retrospective study aimed to investigate the prevalence of serious pathology among adult patients presenting for chiropractic care in an integrated health care organization in Hong Kong, with the hypothesis that the prevalence of these conditions would be lower than 5%.

Material and Methods

STUDY DESIGN:

The Ethics Committee of the Chiropractic Doctors Association of Hong Kong approved this study and granted a waiver of patient consent (Causeway Bay, Hong Kong; IRB ID: CDA20220731). The current study is based on a registered protocol (Open Science Framework, DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/8NVQE [29]), and is a retrospective chart review of routinely collected clinical data, with the data query and abstraction occurring in August 2022.

The current study utilized convenience sampling to identify all patients with low back pain within the study time window [30]. After this population was defined, patients with suspected serious pathology were identified from within this population by searching a custom messaging system and medical records data (see Data Source). Convenience sampling was most appropriate given the low expected prevalence of serious pathology among patients with low back pain, whereas other methods of sampling (eg, random or systemic sampling of every nth record) would limit sample size and thus not be practical [31].

SETTING:

The current chart review included 30 chiropractic clinics which employed 38 full-time chiropractors during the study time window (January 1, 2020, through July 31, 2022). These chiropractic clinics are integrated within a larger healthcare organization (EC Healthcare, Hong Kong), which has several medical specialty departments pertinent to triage and further assessment of suspected serious pathology, including, but not limited to cardiology, oncology, gastroenterology, general surgery, hematology & hematological oncology, neurosurgery, orthopedics, otorhinolaryngology, urology, and respiratory medicine. These providers typically evaluate cases of suspected serious pathology when identified by a chiropractor unless patients are referred directly to an outside emergency department. The affiliated chiropractic clinics and larger health care organization accept both insurance and cash for services.

The need for imaging is dependent on the chiropractor’s clinical judgement and may involve radiography, MRI, or other types of imaging. However, the clinics examined in the current study have a high utilization rate of imaging. According to unpublished quality control data from these clinics, in which 5 cases from each chiropractor are audited each month, 95% of patients either present with imaging taken at a previous center or receive imaging after presentation. In the case of potential serious pathology, radiologists write an alert, which is sent in a custom messaging system to the treating chiropractor and supervising chiropractic provider (EC). This alert also includes recommendations for next steps including potential referral (eg, orthopedics, oncology, emergency medical services) or additional imaging studies (eg, MRI). The chiropractor may then request a consultation with one of the medical specialists, in which this provider may review the imaging. Further, the specialist may then see the patient either in person or via telemedicine, and/or follow one or more suggested management strategies from the radiology team.

The imaging centers within the affiliated healthcare organization (Hong Kong Advanced Imaging, EC Healthcare) have the capability to perform radiographs, MRI, computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography, and utilize various imaging contrast agents. Radiologists who interpret images are board-certified medical physicians.

The chiropractors included in these clinics were all board-certified licensed providers. While they were trained in different institutions internationally, these providers share similar practice characteristics. Chiropractic providers in the current study followed a clinic handbook and underwent an extensive 3-month training upon being hired, which included direct supervision by the lead author of the current study (EC). Chiropractors may order imaging studies in Hong Kong as part of their scope of practice.

DATA SOURCE:

Data were obtained from a custom electronic health records system (CSP, EC Healthcare) shared by the affiliated chiropractic clinics and wider parent healthcare organization. Radiology reports are also available within this records system. Data queries and extraction were performed by 3 information technology professionals who were blinded to the study hypotheses. Any discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by mutual discussion.

This medical records system was searched by free text in August 2022 for instances of “low back pain” and a synonym, “lumbago,” with patients being required to have 1 of these terms present in their record, to identify the number of patients presenting with low back pain complaints for chiropractic care within the study time window of January 1, 2020, through July 31, 2022. Patients with severe pathology were identified by searching a messaging service used by the clinical and radiology staff to provide alerts in cases of suspected serious pathology or patients in need of urgent medical attention. The medical records of these patients were hand-searched for additional clinical details. Data was also available from patient intake paperwork, imaging requisition forms, and records derived from long-term follow-up queries sent to patients 1 year following their final chiropractic visit.

Data were entered into a pre-defined spreadsheet and subsequently checked by the study investigators for accuracy by EC, and further checked for errors and consistency and harmonized to common terminology by RT.

PARTICIPANTS:

Patients were required to be at least 18 years of age and must not have been previously seen within the healthcare organization for low back pain. Therefore, patients could either be presenting new to the clinic altogether with low back pain or could be presenting with a new concern of low back pain, having been previously seen for another concern (eg, neck pain, headache). There was no washout period used, and patients could have seen providers at outside healthcare organizations for their low back pain previously. Low back pain was defined as symptoms between the level of T12 and the gluteal fold [2] of any duration.

For the population defined as having serious pathology, patients were required to have either a spinal infection, fracture, malignancy, or cauda equina syndrome, in accordance with previous publications on this topic [1–5], which was previously undiagnosed, and was subsequently confirmed via imaging and follow-up testing with medical specialist(s). Any condition requiring immediate or urgent surgical or non-conservative medical intervention(s) within 30 days was also considered serious pathology according to a previous definition [5]. These were determined on a case-by-case basis by the study investigators by mutual agreement. Cauda equina syndrome was diagnosed when there was both imaging evidence and clinical findings of cauda equina compression [32], but cases of slow-onset cauda equina symptoms in elderly individuals were excluded given these cases do not require emergent or urgent treatment [33]. Likewise, inflammatory back pain such as ankylosing spondylitis [34], remote/chronic vertebral fracture or pars interarticularis defects were not considered serious pathology in the current study, as these do not require urgent treatment. Radiologists at the study sites used a threshold of at least 4 centimeters of anteroposterior diameter to define the presence of an aortic aneurysm, and when present, reported these cases in the messaging system for suspected serious pathology. These cases were only considered serious in the current study when they required urgent surgical treatment [35].

VARIABLES:

Patient data were recorded in a manner that eliminated patient identifiers. Patient demographics included age in years at the time of initial presentation and sex. The patient’s chief concern was recorded in free text and harmonized according to a consistent terminology by RT. Low back pain with lower extremity symptoms was used to denote any description of low back pain with radiation into the lower extremities or associated sensory or motor symptoms in the lower extremities. Whether the patient saw a provider previously for their episode of low back pain was recorded as yes, no, or unclear. Pain severity at the time of presentation to the chiropractor was reported as a number from 0 to 10 according to the numeric pain rating scale, in which 0 is no pain and 10 is the most severe pain.

Red flags, which are potential indicators of serious pathology [35], were extracted based on standard lists of red flags for low back pain described in the literature [36]. Examples included a history of cancer, night pain, or history of a fall [36]. Because red flags are variable between references [34,36], the current study included an age of at least 70 years as a red flag (rather than greater than 50). The current study did not include “insidious onset” or signs of inflammatory low back pain such as morning stiffness, which are inconsistently recognized as red flags [34,36].

The imaging modality was categorized as radiography, MRI, computed tomography, or positron emission tomography. Only tests ordered by the chiropractor were included for this variable, rather than follow-up testing ordered by a medical specialist. The region of imaging was extracted from the imaging report, and was categorized as lumbar spine, pelvis, hip, thoracic, cervical, or other regions in free text. Imaging findings were listed in free text as reported in the radiologist’s impression in the imaging report. These were later shortened and categorized by RT.

The final diagnosis was either obtained from the imaging report, if conclusive (eg, fracture), or further specialist testing (eg, metastasis), which was extracted from the shared electronic health records system. The management strategy consisted of the initial referral initiated by the chiropractor after suspecting or identifying serious pathology. This variable was reported as the type of medical specialist (eg, orthopedist, oncologist) or emergency medical services. Follow-up treatments were also listed in free text and later categorized by RT.

MISSING DATA:

As cases were required to have confirmation of serious pathology to be included, cases without available follow-up data were excluded. Variables that were unavailable were labeled as “unclear.”

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Statistical analysis was carried out using GNU PSPP Statistical Analysis Software (V.1.0.1). Descriptive statistics were used to calculate prevalence, frequency, mean, and standard deviation for each of the measured variables. Based on a similar previous study [2], we required at least 10 cases of severe pathology but did not utilize a robust sample size calculation. This sample was expected to be feasible given the extensive query window of 31 months, inclusion of several chiropractic clinics, and previous case reports from this clinic system describing severe pathology identified by chiropractors [37].

Results

PARTICIPANTS:

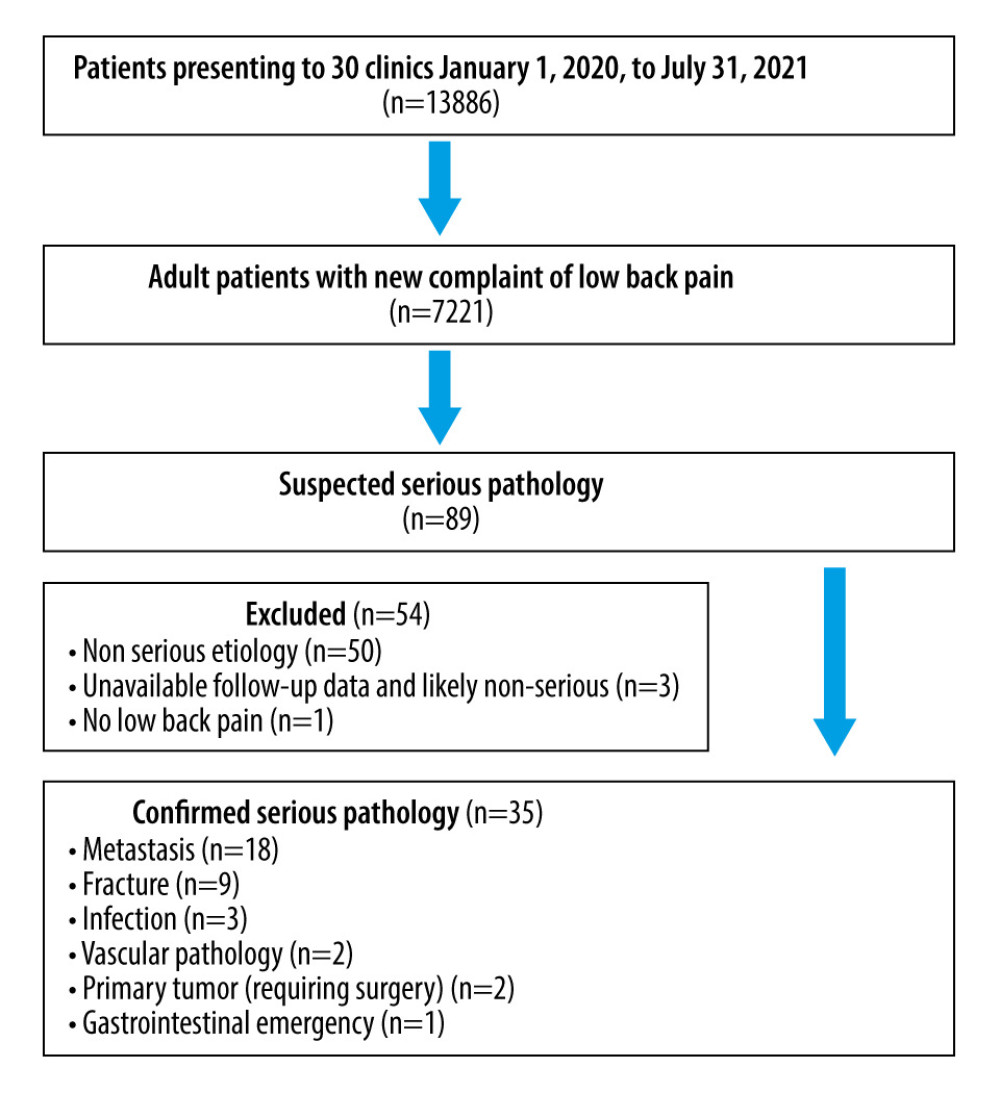

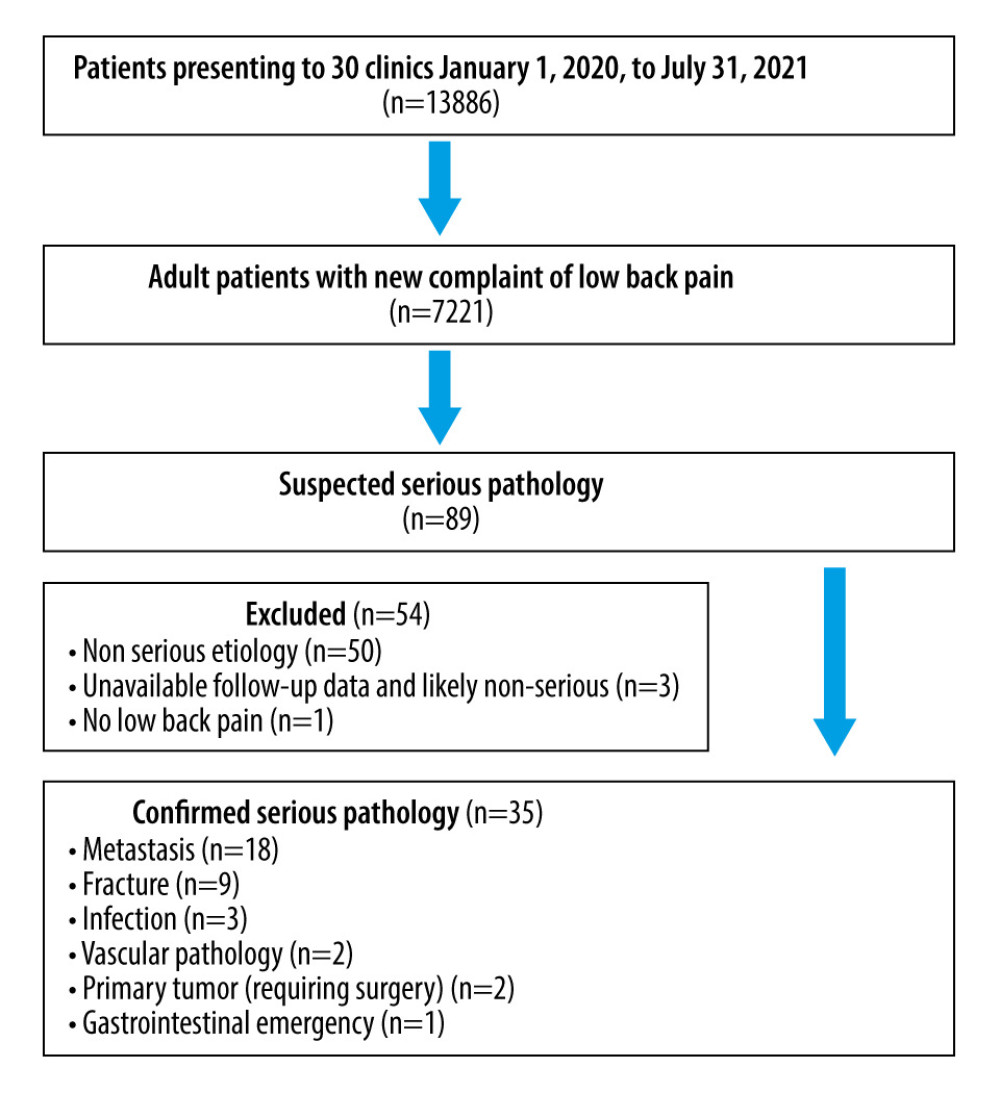

There were 7221 patients who presented with low back pain to a chiropractor from January 2020 to July 31, 2022. Of these patients, 89 had suspected serious pathology, 35 of which had confirmed serious pathology (mean age 61.6±14.3, 57% male; Figure 1). Additional patient-level data are available as a supplementary file in the open access repository Figshare (https://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20509380). Several cases of suspected serious pathology were excluded (n=54). The largest category of excluded patients had findings deemed to be non-serious upon follow-up testing (n=50). Specifically, these excluded cases with an incidental finding of a lung nodule (n=20), patients with imaging evidence of cauda equina compression that did not meet our clinical criteria for acute cauda equina syndrome (n=13), degenerative cervical myelopathy in patients with tandem stenosis (n=4), a pancreatic, renal, or adrenal cyst or nodule determined to be benign (n=4), benign vertebral hemangioma or sclerotic bone lesion (n=3), situs inversus totalis (n=1), uterine fibroids (n=1), non-urgent urolithiasis (n=1), bladder wall thickening (n=1), lymph node enlargement (n=1), and suspected ankylosing spondylitis (n=1). One patient was excluded who did not have low back pain (n=1). Other cases were excluded that were likely non-serious; however, there were no follow-up data available, including dilated bowel loops, a lung abnormality, and lymph node enlargement (n=3).

Among the included patients with serious pathology, all had low back pain, while 28/35 (80%) also had some type of lower extremity symptoms such as pain, paresthesia, numbness, or weakness, while 1/35 (3%) had low back and hip pain and 1/35 (3%) had low back and interscapular pain. The mean baseline pain severity was 7.3±1.3 out of 10. Two-thirds of patients (22/35, 63%) had at least 1 red flag, such as a history of cancer, age of at least 70, trauma, or night pain, while 9/35 (26%) had 2 or more red flags. Most patients had previously seen another health care provider (27/35, 77%), while a minority did not (2/35, 6%) or it was unclear if they had seen another provider for this specific concern (6/35, 17%).

The most common imaging modality was MRI (30/35, 86%), followed by radiograph (4/35, 11%), and CT (1/35, 3%). The most common imaging location was the lumbar spine (30/35, 86%), followed by multiple spinal regions (4/35, 11%), and abdomen (1/35, 3%).

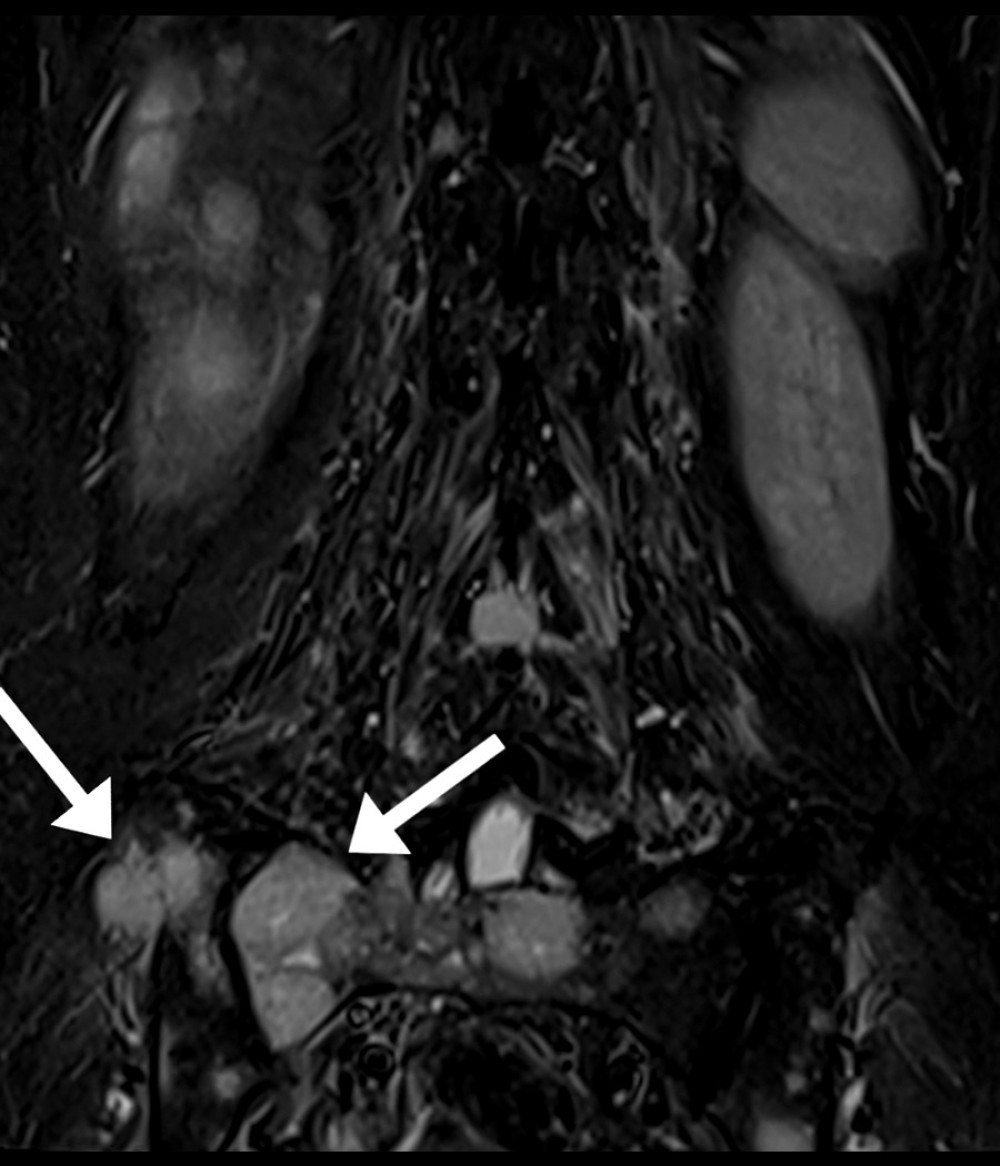

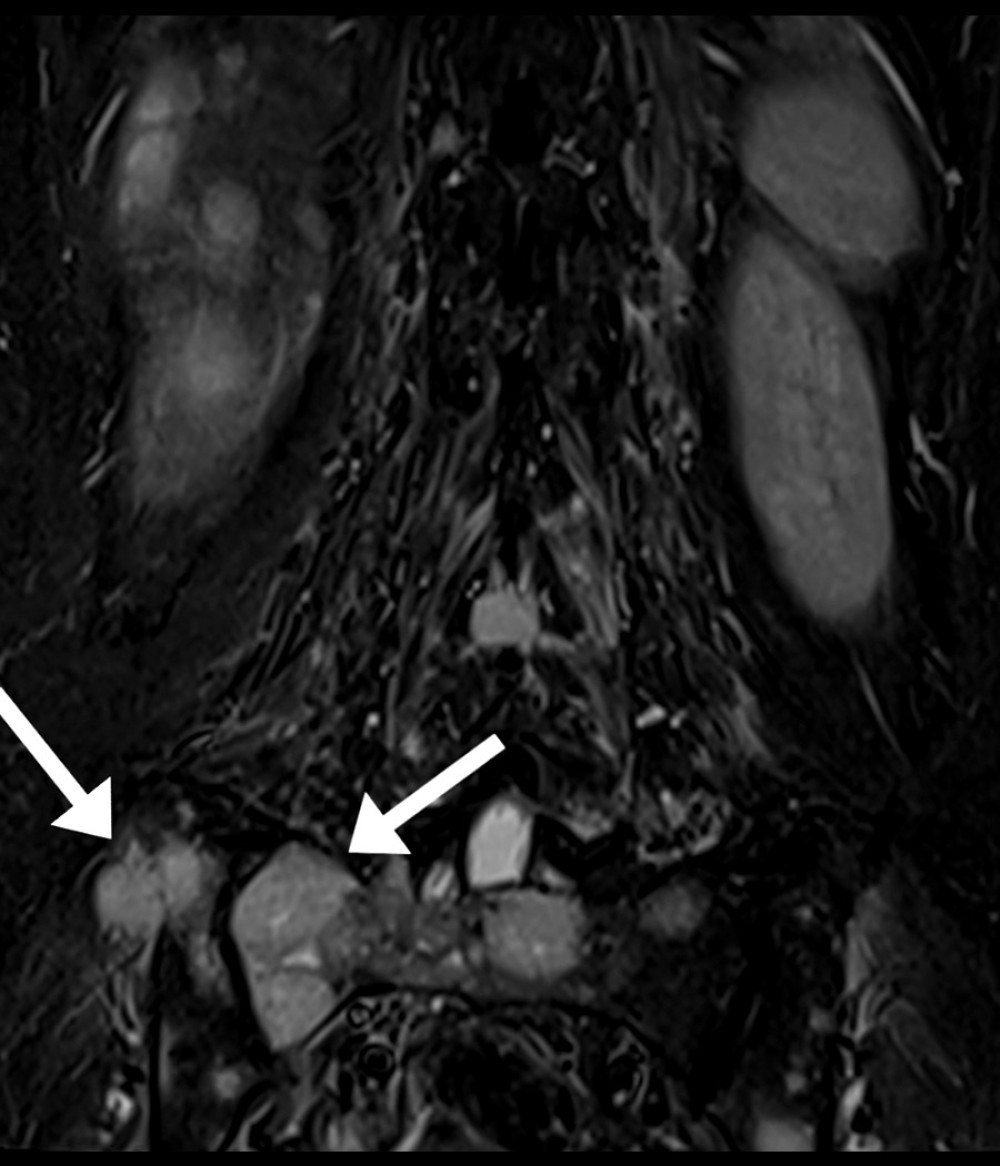

The most common diagnosis of serious pathology was metastasis (18/35, 51%; Figure 2), followed by fracture (9/35, 26%; Figure 3), infection including 2 cases of spinal abscess/osteomyelitis and 1 case of osteomyelitis (3/35, 9%; Figure 4), vascular pathology including abdominal aortic aneurysm or spinal epidural hematoma (2/35, 6%), primary tumors which were malignant, aggressive, and/or requiring urgent surgery (2/35, 6%), or a gastrointestinal emergency of cholecystitis (1/35, 3%).

Chiropractors initially referred the patients most often to an oncologist (20/35, 57%), followed by orthopedist or orthopedic surgeon (12/35, 34%), emergency department (2/35, 6%), or vascular surgeon (1/35, 3%). Initial treatment included non-chemotherapy medications such as antibiotics, pain medications, or other conservative therapies such as application of a back brace (17/35, 49%), chemotherapy (10/35, 29%), surgery (4/35, 11%), and chemotherapy and surgery (4/35, 11%).

KEY RESULTS:

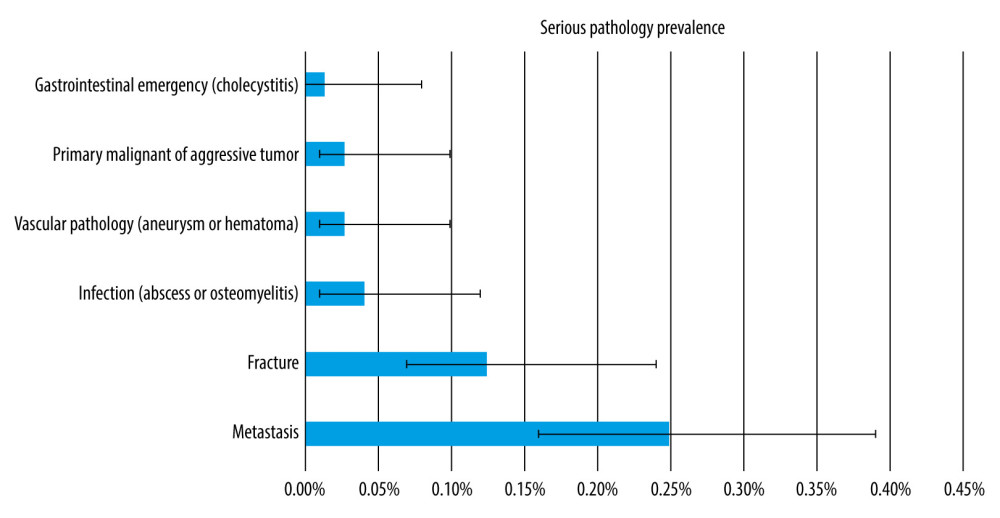

The overall prevalence of serious pathology was calculated as a proportion of the total number of low back pain cases (ie, 35/7,221), yielding a point estimate (95% CI) of 0.48% (0.35–0.67%). The prevalence point estimates (95% CI) of cases of serious pathology per category (Figure 5) was calculated as a proportion of the total cases of low back pain (7221): Metastasis (0.25%; 0.16–0.39%), fracture (0.12%; 0.07–0.24%), infection (0.04%; 0.01–0.12%), vascular pathology (0.03%; 0.01–0.10%), primary tumor (0.03%; 0.01–0.10%), and gastrointestinal emergency (0.01%; 0.00–0.08%).

ADDITIONAL ANALYSIS:

A post hoc analysis was conducted to estimate the frequency at which a single chiropractor would encounter a case of serious pathology. Given there were 35 cases of serious pathology for 38 full-time chiropractors over a span of 31 months, this equaled 0.92 cases per chiropractor during this time frame. This was converted after multiplying by a factor of 1.09 to yield 1.0 case per chiropractor for every 34 months, or, stated differently, 1 case per chiropractor every 2.8 years.

Discussion

LIMITATIONS:

The present study has several limitations. First, as this was a retrospective study and relied on data entered into the medical record, any patient symptoms or red flags could be inaccurate or missing. Further, as our study utilized a custom alert system, it is possible this system was not used adequately in all cases of serious pathology, and thus cases could have been missed from our query (eg, false negatives), leading to outcome misclassification. Use of this system as opposed to a more comprehensive chart review may have also contributed to sampling bias.

Second, our findings may have limited generalizability to other countries. It is possible that differences in the healthcare system or disease prevalence in Hong Kong would lead to different results compared to other countries.

Third, despite similar training and protocols among the study chiropractors, there could be differences in individual chiropractor approach with regards to patient assessment that led to differences in recording of red flags, variations in ordering diagnostic imaging, or patient management.

Fourth, the current study did not examine the accuracy of red flags in predicting serious pathology, which was beyond the scope of this chart review. However, as previous studies have already shown a low accuracy level of individual red flags, and higher accuracy with combinations of multiple red flags [1,35], our efforts instead focused on a research gap of prevalence of serious pathology in chiropractic offices.

Fifth, our additional analysis for the year-to-case ratio is prone to ecological fallacy given the calculations are based on aggregate data. A more accurate estimate for this value could have been derived by recording the number of cases of serious pathology per provider during the study window and utilizing a regression model, accounting for covariates such as years of experience in practice and provider gender [18]. Some chiropractors may have encountered higher rates of serious pathology than others.

Sixth, a formal sample size calculation was not conducted and was simply based on a minimum number of cases of serious pathology comparable to a prior study [2]. A more robust sample size estimate for the total number of patients with low back pain could have been calculated by using data from a prior similar study which identified a prevalence of serious pathology among patients with low back pain of 0.9% [2]. The formula n=[Z2P(1-P)]/(d2), in which Z equals the Z statistic for the level of confidence of 95% (ie, 1.96), P is the probability of 0.009, and d is the precision, chosen at 0.05% [41], yields a total sample of 1371.

Finally, the high rate of imaging in the current study setting may limit external validity. The rate of imaging in the current study is comparable to a recent survey of chiropractors in Hong Kong, in which 90% of respondents reported they obtained imaging “most of the time.” In comparison, a recent systematic review including an international sample of chiropractic practices reported a lower median (interquartile range) utilization of radiographs (35%; 27–59%), MRI (1%; 1–2%), and computed tomography (2%; 0–2%) as an assessment tool [10].

Conclusions

The current study found that serious pathology was uncommon among adults with new low back pain presenting for chiropractic care in an integrated health care organization in Hong Kong, with a prevalence of 0.48%. This finding is most comparable to previous research describing primary care rather than secondary or tertiary care settings.

Figures

Figure 1. Identification of patients from the electronic health records. Figure created by RT using Microsoft Word (Version 2206).

Figure 1. Identification of patients from the electronic health records. Figure created by RT using Microsoft Word (Version 2206).  Figure 2. Spinal metastasis. This 53-year-old woman with a remote history of breast cancer presented to a chiropractor with a 3-month history of progressively worsening low back pain with radiation into the lower extremities bilaterally and lower extremity weakness. She previously presented to the emergency department and had been referred for physical therapy. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging showed several findings consistent with bony metastasis, including lesions of the sacrum and ilium (arrows in T2-weighted coronal image), liver, and lumbar spine. The patient was referred to an oncologist for further management. Arrows added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).

Figure 2. Spinal metastasis. This 53-year-old woman with a remote history of breast cancer presented to a chiropractor with a 3-month history of progressively worsening low back pain with radiation into the lower extremities bilaterally and lower extremity weakness. She previously presented to the emergency department and had been referred for physical therapy. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging showed several findings consistent with bony metastasis, including lesions of the sacrum and ilium (arrows in T2-weighted coronal image), liver, and lumbar spine. The patient was referred to an oncologist for further management. Arrows added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).  Figure 3. Osteoporotic compression fracture. This 72-year-old woman presented with a 1-month history of low back pain with radiation into the left paraspinal region and numbness in the left anterior thigh beginning after a fall from ground level onto her knee. She had been receiving acupuncture and traditional bonesetting therapy and had no previous imaging. The T12 vertebral body shows marrow edema and a hypointense horizontal fracture line is noted in this T2-weighted mid-sagittal image (arrow), which remains hypointense in T1-weighted images (not shown). The patient was referred to an orthopedist but was ultimately treated conservatively. Arrow added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).

Figure 3. Osteoporotic compression fracture. This 72-year-old woman presented with a 1-month history of low back pain with radiation into the left paraspinal region and numbness in the left anterior thigh beginning after a fall from ground level onto her knee. She had been receiving acupuncture and traditional bonesetting therapy and had no previous imaging. The T12 vertebral body shows marrow edema and a hypointense horizontal fracture line is noted in this T2-weighted mid-sagittal image (arrow), which remains hypointense in T1-weighted images (not shown). The patient was referred to an orthopedist but was ultimately treated conservatively. Arrow added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).  Figure 4. Spinal infection. This 50-year-old man who was previously healthy reported acute-onset low back pain which progressively worsened over the prior week, causing him to be unable sleep or stand upright. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging showed a 3.2×3.1×3.0-centimeter T2-weighted hyperintense lobulated lesion at the left L5/S1 paraspinal region involving the left psoas muscle (arrowhead in axial T2-weighted axial image), with apparent connection with the left side of the intervertebral disc. The chiropractor consulted with an on-site orthopedic surgeon and referred the patient to the emergency department, where he was treated for a psoas abscess and spondylodiscitis. Arrow added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).

Figure 4. Spinal infection. This 50-year-old man who was previously healthy reported acute-onset low back pain which progressively worsened over the prior week, causing him to be unable sleep or stand upright. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging showed a 3.2×3.1×3.0-centimeter T2-weighted hyperintense lobulated lesion at the left L5/S1 paraspinal region involving the left psoas muscle (arrowhead in axial T2-weighted axial image), with apparent connection with the left side of the intervertebral disc. The chiropractor consulted with an on-site orthopedic surgeon and referred the patient to the emergency department, where he was treated for a psoas abscess and spondylodiscitis. Arrow added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).  Figure 5. Prevalence of serious pathology among patients with new low back pain presenting to a chiropractor. Error bars indicate 95% CI for point estimates. Image created by RT using Microsoft Excel (Version 2206).

Figure 5. Prevalence of serious pathology among patients with new low back pain presenting to a chiropractor. Error bars indicate 95% CI for point estimates. Image created by RT using Microsoft Excel (Version 2206). References

1. Downie A, Williams CM, Henschke N, Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: Systematic review: BMJ, 2013; 347; f7095

2. Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain: Arthritis Rheum, 2009; 60; 3072-80

3. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Turko E, Ansell D, Risk factors for serious underlying pathology in adult Emergency Department nontraumatic low back pain patients: J Emerg Med, 2014; 47; 1-11

4. Finucane LM, Downie A, Mercer C, International framework for red flags for potential serious spinal pathologies: J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2020; 50; 350-72

5. Galliker G, Scherer DE, Trippolini MA, Low back pain in the emergency department: prevalence of serious spinal pathologies and diagnostic accuracy of red flags: Am J Med, 2020; 133; 60-72

6. Kovach S, Huslig E, Prevalence of diagnoses on the basis of radiographic evaluation of chiropractic cases: J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 1983; 6; 197-201

7. Beck RW, Holt KR, Fox MA, Hurtgen-Grace KL, Radiographic anomalies that may alter chiropractic intervention strategies found in a New Zealand population: J Manipulative Physiol Therap, 2004; 27; 554-59

8. Young KJ, Aziz A, An accounting of pathology visible on lumbar spine radiographs of patients attending private chiropractic clinics in the United Kingdom: Chiropractic Journal of Australia, 2009; 39; 63-69

9. Brown MJ, Prevalence of pathology seen on lumbar x-rays in patients over the age of 50 years: The British Journal of Chiropractic, 2001; 5; 23-30

10. Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, The chiropractic profession: A scoping review of utilization rates, reasons for seeking care, patient profiles, and care provided: Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, 2017; 25; 35

11. Murphy DR, Justice B, Bise CG, The primary spine practitioner as a new role in healthcare systems in North America: Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, 2022; 30; 6

12. Schneider M, Murphy D, Hartvigsen J, Spine Care as a framework for the chiropractic identity: J Chiropr Humanit, 2016; 23; 14-21

13. Laoudikou MT, McCarthy PW, Patients with cancer. Is there a role for chiropractic?: J Can Chiropr Assoc, 2020; 64; 32-42

14. Chang M, The chiropractic scope of practice in the United States: A cross-sectional survey: J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 2014; 37; 363-76

15. Jenkins HJ, Downie AS, Moore CS, French SD, Current evidence for spinal X-ray use in the chiropractic profession: A narrative review: Chiropr Man Therap, 2018; 26; 48

16. Shah LM, Salzman KL, Imaging of spinal metastatic disease: Int J Surg Oncol, 2011; 2011; e769753

17. Davies AM, Fowler J, Tyrrell PNM, Detection of significant abnormalities on lumbar spine radiographs: Br J Radiol, 1993; 66; 37-43

18. Daniel DM, Ndetan H, Rupert RL, Martinez D, Self-reported recognition of undiagnosed life threatening conditions in chiropractic practice: A random survey: Chiropr Man Therap, 2012; 20; 21

19. Himelfarb I, Hyland J, Ouzts N: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners: Practice analysis of chiropractic 2020 [Internet], 2020, Greeley, CO, NBCE [cited 2020 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.nbce.org/practice-analysis-of-chiropractic-2020/

20. Pannucci CJ, Wilkins EG, Identifying and avoiding bias in research: Plast Reconstr Surg, 2010; 126; 619-25

21. Trager RJ, Anderson BR, Casselberry RM, Guideline-concordant utilization of magnetic resonance imaging in adults receiving chiropractic manipulative therapy vs other care for radicular low back pain: A retrospective cohort study: BMC Musculoskel Disord, 2022; 23; 554

22. Hurwitz EL, Epidemiology: Spinal manipulation utilization: J Electromyogr Kinesiol, 2012; 22; 648-54

23. Peterson CK, Gatterman MI: The nonmanipulable subluxation Foundations of chiropractic: Subluxation, 2005; 168-90, St Louis, Mosby Yearbook Inc

24. Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, French SD, Rubinstein SM, Serious adverse events and spinal manipulative therapy of the low back region: A systematic review of cases: J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 2015; 38; 677-91

25. Souza T: Lumbopelvic complaints Differential diagnosis and management for the chiropractor: Protocols and algorithms, 2008; 143-201, Sudbury, Mass, Jones & Bartlett Learning

26. Evans RC, Illustrated orthopedic physical assessment: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2008

27. Puhl AA, Reinhart CJ, Injeyan HS, Diagnostic and treatment methods used by chiropractors: A random sample survey of Canada’s English-speaking provinces: J Can Chiropr Assoc, 2015; 59; 279-87

28. Triano JJ, Budgell B, Bagnulo A, Review of methods used by chiropractors to determine the site for applying manipulation: Chiropr Man Therap, 2013; 21; 36

29. Trager RJ, Chu EC-P, Prevalence of severe pathology among adults with low back pain presenting for chiropractic care: Protocol for a retrospective chart review of multidisciplinary clinics in Hong Kong. OSF, 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 30]; Available from: https://osf.io/8nvqe

30. Worster A, Haines T, Advanced statistics: Understanding Medical Record Review (MRR) Studies: Acad Emerg Med, 2004; 11; 187-92

31. Vassar M, Matthew H, The retrospective chart review: Important methodological considerations: J Educ Eval Health Prof, 2013; 10; 12

32. Fraser S, Roberts L, Murphy E, Cauda equina syndrome: A literature review of its definition and clinical presentation: Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2009; 90; 1964-68

33. Comer C, Finucane L, Mercer C, Greenhalgh S, SHADES of grey – the challenge of ‘grumbling’ cauda equina symptoms in older adults with lumbar spinal stenosis: Musculoskelet Sci Pract, 2020; 45; 102049

34. Street KJ, Serious pathologies in the lumbar spine: prevalence and diagnostic accuracy of red flag questions [Internet]: PhD Thesis, 2016, Auckland, New Zealand, Auckland University of Technology Available from: https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10292/10216/StreetK.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

35. Premkumar A, Godfrey W, Gottschalk MB, Boden SD, Red flags for low back pain are not always really red: A prospective evaluation of the clinical utility of commonly used screening questions for low back pain: J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2018; 100; 368-74

36. Verhagen AP, Downie A, Popal N, Red flags presented in current low back pain guidelines: A review: Eur Spine J, 2016; 25; 2788-802

37. Chu E, Large abdominal aortic aneurysm presented with concomitant acute lumbar disc herniation – a case report: J Med Life, 2022; 15; 871-75

38. Wanhainen A, Björck M, Boman K, Influence of diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm: J Vasc Surg, 2001; 34; 229-35

39. Chan WK, Yong E, Hong Q, Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in Asian populations: J Vasc Surg, 2021; 73; 1069-1074e1

40. Trager RJ, Dusek JA, Chiropractic case reports: A review and bibliometric analysis: Chiropr Man Therap, 2021; 29; 17

41. Daniel WW, Cross CL: Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences, 2018, Wiley

Figures

Figure 1. Identification of patients from the electronic health records. Figure created by RT using Microsoft Word (Version 2206).

Figure 1. Identification of patients from the electronic health records. Figure created by RT using Microsoft Word (Version 2206). Figure 2. Spinal metastasis. This 53-year-old woman with a remote history of breast cancer presented to a chiropractor with a 3-month history of progressively worsening low back pain with radiation into the lower extremities bilaterally and lower extremity weakness. She previously presented to the emergency department and had been referred for physical therapy. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging showed several findings consistent with bony metastasis, including lesions of the sacrum and ilium (arrows in T2-weighted coronal image), liver, and lumbar spine. The patient was referred to an oncologist for further management. Arrows added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).

Figure 2. Spinal metastasis. This 53-year-old woman with a remote history of breast cancer presented to a chiropractor with a 3-month history of progressively worsening low back pain with radiation into the lower extremities bilaterally and lower extremity weakness. She previously presented to the emergency department and had been referred for physical therapy. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging showed several findings consistent with bony metastasis, including lesions of the sacrum and ilium (arrows in T2-weighted coronal image), liver, and lumbar spine. The patient was referred to an oncologist for further management. Arrows added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30). Figure 3. Osteoporotic compression fracture. This 72-year-old woman presented with a 1-month history of low back pain with radiation into the left paraspinal region and numbness in the left anterior thigh beginning after a fall from ground level onto her knee. She had been receiving acupuncture and traditional bonesetting therapy and had no previous imaging. The T12 vertebral body shows marrow edema and a hypointense horizontal fracture line is noted in this T2-weighted mid-sagittal image (arrow), which remains hypointense in T1-weighted images (not shown). The patient was referred to an orthopedist but was ultimately treated conservatively. Arrow added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).

Figure 3. Osteoporotic compression fracture. This 72-year-old woman presented with a 1-month history of low back pain with radiation into the left paraspinal region and numbness in the left anterior thigh beginning after a fall from ground level onto her knee. She had been receiving acupuncture and traditional bonesetting therapy and had no previous imaging. The T12 vertebral body shows marrow edema and a hypointense horizontal fracture line is noted in this T2-weighted mid-sagittal image (arrow), which remains hypointense in T1-weighted images (not shown). The patient was referred to an orthopedist but was ultimately treated conservatively. Arrow added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30). Figure 4. Spinal infection. This 50-year-old man who was previously healthy reported acute-onset low back pain which progressively worsened over the prior week, causing him to be unable sleep or stand upright. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging showed a 3.2×3.1×3.0-centimeter T2-weighted hyperintense lobulated lesion at the left L5/S1 paraspinal region involving the left psoas muscle (arrowhead in axial T2-weighted axial image), with apparent connection with the left side of the intervertebral disc. The chiropractor consulted with an on-site orthopedic surgeon and referred the patient to the emergency department, where he was treated for a psoas abscess and spondylodiscitis. Arrow added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30).

Figure 4. Spinal infection. This 50-year-old man who was previously healthy reported acute-onset low back pain which progressively worsened over the prior week, causing him to be unable sleep or stand upright. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging showed a 3.2×3.1×3.0-centimeter T2-weighted hyperintense lobulated lesion at the left L5/S1 paraspinal region involving the left psoas muscle (arrowhead in axial T2-weighted axial image), with apparent connection with the left side of the intervertebral disc. The chiropractor consulted with an on-site orthopedic surgeon and referred the patient to the emergency department, where he was treated for a psoas abscess and spondylodiscitis. Arrow added by RT using GNU Image Manipulation Program (Version 2.10.30). Figure 5. Prevalence of serious pathology among patients with new low back pain presenting to a chiropractor. Error bars indicate 95% CI for point estimates. Image created by RT using Microsoft Excel (Version 2206).

Figure 5. Prevalence of serious pathology among patients with new low back pain presenting to a chiropractor. Error bars indicate 95% CI for point estimates. Image created by RT using Microsoft Excel (Version 2206). In Press

05 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Muscular Function Recovery from General Anesthesia in 132 Patients Undergoing Surgery with Acceleromyograph...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942780

05 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Effects of Thermal Insulation on Recovery and Comfort of Patients Undergoing Holmium Laser LithotripsyMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942836

05 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Role of Critical Shoulder Angle in Degenerative Type Rotator Cuff Tears: A Turkish Cohort StudyMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943703

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Outcomes between Single-Level and Double-Level Corpectomy in Thoracolumbar Reconstruction: A ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943797

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952