08 March 2024: Clinical Research

Ecoepidemiology of spp. in Urban-Marginal and Rural Sectors of the Ecuadorian Coast and Prevalence of Cutaneous Larvae Migrans

Roberto Darwin Coello PeraltaDOI: 10.12659/MSM.943931

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e943931

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Ancylostoma spp., including A. duodenale, A. braziliense, A. caninum, and A. ceylanicum, are hookworms that are transmitted from infected soil and by contact with domestic animals and rodent hosts, and can cause systemic disease and cutaneous larva migrans. The objective of this study was to describe the ecoepidemiology of Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma spp. in urban-marginal sectors and in rural sectors located in Ecuador.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: Through addressed sampling, a total of 498 domestic dogs and 40 synanthropic rodents were analyzed via the following coproparasitic methods: direct, flotation, sedimentation with centrifugation using saline (egg identification), modified Baermann (larval identification), and morphometric methods (confirmation). A total of 236 people were surveyed, and a clinical analysis was performed via physical examination. The environmental variables were obtained through reports from the INAMHI of Ecuador and the use of online environmental programs. Through surveys, data related to social determinants were obtained. Epidemiological indicators (prevalence, morbidity, and mortality) were obtained through microbial analysis and surveys.

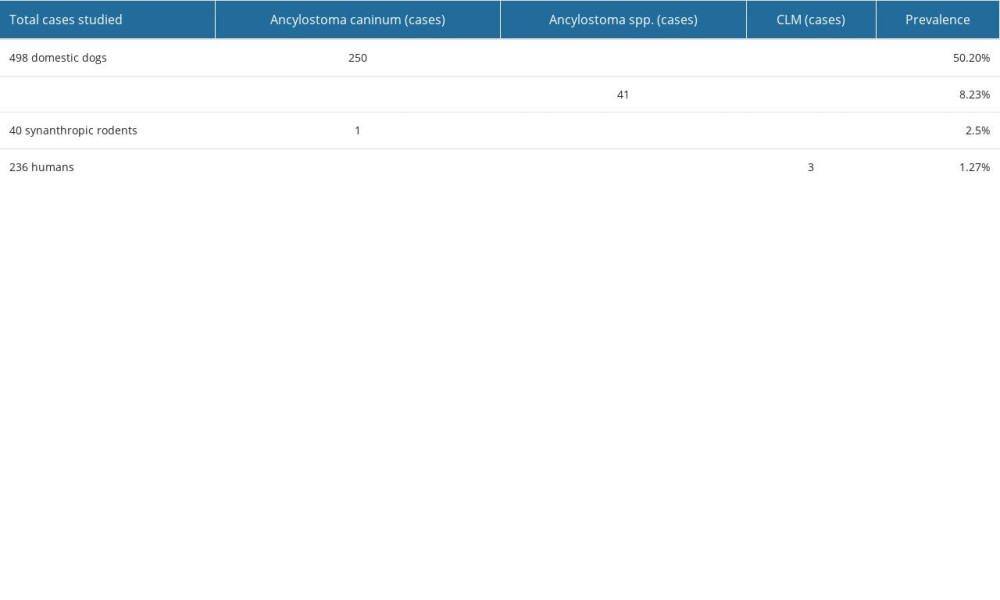

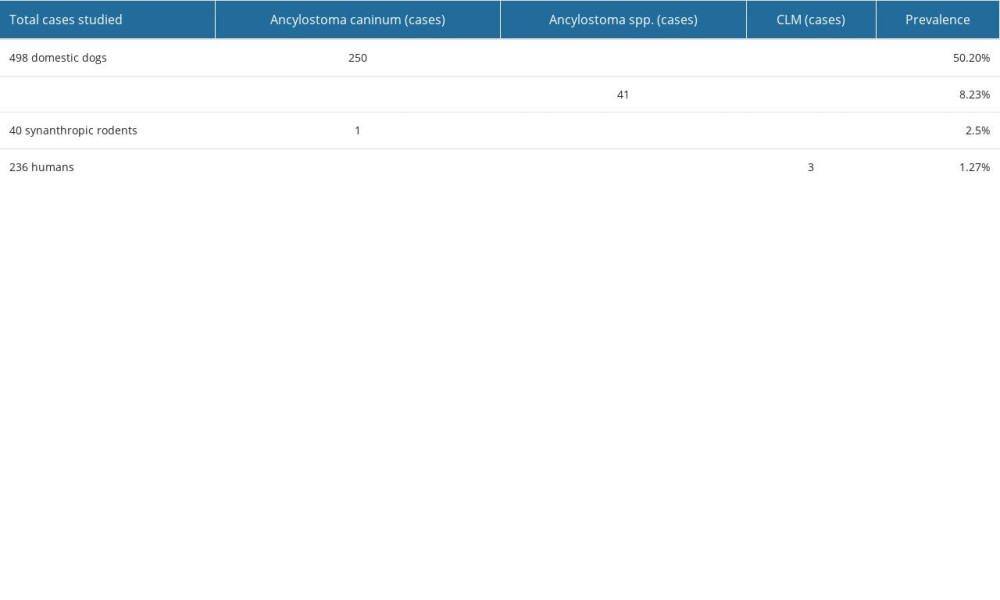

RESULTS: A total of 250 domestic dogs were diagnosed with Ancylostoma caninum (50, 20%), and 41 were diagnosed with Ancylostoma spp. (8.23%). One synanthropic rodent (2.5%) was positive for A. caninum. In the clinical analysis, 3 patients were identified as positive (1.27%) for cutaneous larva migrans (CLM). Likewise, environmental variables and social determinants influence the transmission, prevalence, and nature of parasitism by hookworm.

CONCLUSIONS: People, domestic dogs, and rodents were infected with these parasites. Consequently, there is a risk of ancylostomiasis and cutaneous larvae migrans spreading.

Keywords: Parasitology, Zoonoses, Tropical Medicine, Ancylostomiasis, Larva Migrans

Background

Ecoepidemiology is a branch of ecology in which the synthropism between a pathogen and its hosts (animal and human) and the environment is studied; this process usually manifests itself as the spread of infectious diseases in any region of the world, especially in countries with tropical and subtropical climates [1].

Ecuador is a tropical country located on the equator. It is one of 17 countries with the greatest biodiversity on the planet and is characterized by a range of climates in its 4 regions (coastal, Andes, Amazon, and Galapagos Islands), with abundant flora and fauna. The Ecuadorian coast is influenced by warm El Niño currents and cold Humboldt currents. Within the country, there is little information on soil-transmitted helminth infections, especially ancylostomiasis, which affects urban and rural populations and is related to tropical wildlife and the presence of certain animals in established risk areas [2].

Ancylostomiasis is one of the most common chronic infections, with an estimated 1.5 billion cases worldwide [3], and is directly responsible for 65 000 deaths per year. The disease is persistent in places with poor environmental sanitation and high humidity. Its clinical manifestations in humans include chronic intestinal blood loss, iron deficiency anemia and cutaneous larva migrans; it is a serious public health problem [4].

The nematodes that cause ancylostomiasis mainly in humans are

Cutaneous larva migrans manifests with a progressive migratory serpiginous dermal rash, with itching, and commonly appears on the foot. The prevalence worldwide is higher in tropical and very humid countries. The diagnostic method for identification is physical examination. Regarding treatment, albendazole and ivermectin are recommended for oral use; however, thiabendazole (topical) and mebendazole (oral) can be used [7].

Rodents are reservoirs and carriers of several zoonotic parasites that can be transmitted to humans [9]. Stray and house-dwelling dogs, as well as rodents, play an important role in disease transmission [9,10]. Furthermore, the presence of hookworm infections among domestic dogs, rodents, and humans, and the socioecoepidemiological relationships of these infections in Ecuador and Latin America are unknown [5,8].

This study was part of the FCI-029 Project (Competitive Research Fund) approved and financed by the University of Guayaquil (UG) of Ecuador: Ecoepidemiology of Neglected Intestinal Helminthiases in Urban-Marginal and Rural Areas of the Guayas Province. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of

Material and Methods

ETHICS STATEMENT:

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Council of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics (FMVZ) of the University of Guayaquil (UG), the Research Department of the University of Guayaquil (DIUG) and the Ethics Committee of the University of Guayaquil, Ecuador. This was an observational, cross-sectional study with a mixed approach.

SAMPLING AREAS:

Fecal samples of domestic dogs, synanthropic rodents, and humans were collected through non-probabilistic addressed sampling from the urban-marginal sectors of Guayaquil, including Balerio Estacio and La Ladrillera (2°11′24″ S; 79°53′15″ W; 4 masl), and from rural sectors including Loma Larga (1°55′00″ S; 80°00′42″ W; 7 masl) (of the Nobol Canton) and Santa Rosa (1°52′00″ S; 79°59′00″ W; 9 masl) (of the Daule Canton), which are located in the province of Guayas on the Ecuadorian coast and have a tropical savanna climate. The sites investigated differ markedly between winter (rainy and hot) and summer (dry and cooler), with temperatures ranging from 20°C to 37°C.

UNIVERSE AND SAMPLE:

Due to the absence of a census of domestic dogs, the total human population was used to determine the sample size of the dogs. The population of the 4 zones is 38 057 inhabitants (Balerio Estacio, 32 000 inhabitants; La Ladrillera, 3607, Loma Larga, 1000 inhabitants, and Santa Rosa 1450), housed in 7212 dwellings/households. To calculate the sample size, the WinEpi program was used, with a confidence interval of 95%, a sampling error of 5%, a population size of 7212 (households), and a minimum expected incidence of 5% [11]. According to the calculations, the following were sampled: 59 households per area, with 2 or more dogs and 1 person (the one who is most in contact with the animal) for each household.

RECOGNITION OF AREAS, INFORMED CONSENT, SURVEYS, AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA:

Prior to the investigation, a survey of the areas was carried out, and a talk was held with the local inhabitants, who were told about the ecoepidemiology of the parasite and the risk of acquiring cutaneous larva migrans in humans. In addition, the importance of conducting the study was raised, and the collection and identification of samples from their domestic dogs was explained [12].

Similarly, a survey was conducted with prior informed consent with people who had more than 2 domestic dogs. The topics of the survey were presented as figures and images to help the interviewee answer the questions. Included in these images were epidemiological indicators (prevalence, morbidity and mortality); social variables (number of family members, ages of family members, occupation, tendency to walk barefoot, health system, household infrastructure, presence of sewers and type of water supply, disposal of excreta, keeping of animals and presence of CLM); and environmental parameters (temperature, humidity, precipitation, solar radiation, soil texture, type of vegetation, pH, deforestation, and fauna).

To identify A. caninum, the criteria described by Bowman [13], Botero and Restrepo [14], and Romero Cabello [15] were considered. Coproparasitic methods used – direct, flotation, and sedimentation with centrifugation using saline solution – for identification of eggs, and the modified Baermann method was used for identification of larvae. Finally, the morphometric method was used to confirm the parasite.

ESTIMATION OF EPIDEMIOLOGICAL INDICATORS AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS:

Estimation of epidemiological indicators was carried out with the results of the diagnoses obtained and with the help of the surveys carried out. In the case of social determinants, the results of the surveys were taken into account.

CHARACTERIZATION OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL VARIABLES:

Environmental variables were obtained through environmental programs such as Weather Spark [16], Weather Atlas [17], and meteorological bulletins from the INAMHI [18]. In addition, we used studies described in the Development and Land Management plans carried out by the Decentralized Autonomous Governments of the cities of Guayaquil [19], Nobol [20], and Daule [21].

COLLECTION, TRANSPORT, AND ANALYSIS OF THE SAMPLE OF DOMESTIC DOGS:

For the collection of fecal samples from domestic dogs (from March to September 2023), the owners were given sterile jars, their address and contact number were registered, and a data form was completed. In cases where pet owners could not collect the sample, a technical team collected it [22].

The stool samples of the dogs were immediately transported to the Laboratory of the Veterinary Clinic “Besito Vet Pet Lab” in the city of Guayaquil, where they were analyzed by coproparasitic methods including direct, flotation (Willis), sedimentation with centrifugation using saline solution, and Baermann modified methods. The sections were stained with Lugol solution and observed by light microscopy at 10× and 40× [15,23].

To determine the morbidity of symptomatic animals, the following stool analyses were performed: bacterial (culture and Gram staining), fungal (AFB and lactophenol staining), and viral (antigen for parvovirus and canine distemper).

Notably, all participants or, if the participants were children, guardians, signed the consent form before participating in the study. The participants were fully familiarized with the procedure. The request to sample domestic dogs and rodents was analyzed and approved by the Institutional Committee for the Care and Use of Animals of the FMVZ of the UG.

SAMPLING OF SYNANTHROPIC RODENTS:

The rodents were captured between March 1 to April 28, 2023, in the “La Ladrillera” sector by using 30 Tomahawk and 10 Sherman traps. Nontoxic bait was used (100 g of oats with a quantity of 20 g of peanuts and 5 ml of vanilla, tuna, meat, fish, or fried chicken skin). The traps were strategically placed in landfills, drains, market peripheries, and other places that presented evidence of rodents. Once the live animals were captured, they were sprayed with “Fipronil” insecticide. In the laboratory, the rodents were euthanized by an overdose of 10% ketamine. Subsequently, each rodent was dissected, and its digestive tract was removed. The stool was placed in a Petri dish with physiological solution [24].

The intestinal contents of the animals were analyzed by applying the following coproparasitic methods: direct, flotation and sedimentation-centrifugation with saline solution. Then, the samples were analyzed via optical microscopy using the 10× and 40× objectives [13,15]. The following parameters were recorded: species, sex, and age group following the procedures described by De Sotomayor et al [24].

MORPHOMETRY OF THE PARASITIC FORMS:

All samples that were positive (from domestic dogs and rodents) according to the indicated coproparasitic methods were confirmed by morphometry following the criteria of Bowman [13], Botero and Restrepo [14], Romero Cabello [15], and Lucio et al [25].

IDENTIFICATION OF CUTANEOUS LARVA MIGRANS:

The presence of cutaneous larva migrans was determined by physical examination of each patient.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The data obtained were tabulated and are presented in tables generated using the Microsoft Excel 2010 program. In addition, the prevalence of canine ancylostomiasis and CLM was related to social, environmental, and epidemiological indicators through inferential statistical analysis performed with RStudio statistical software. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze these data. Finally, a generalized linear model (GLM) was implemented.

Results

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL INDICATORS:

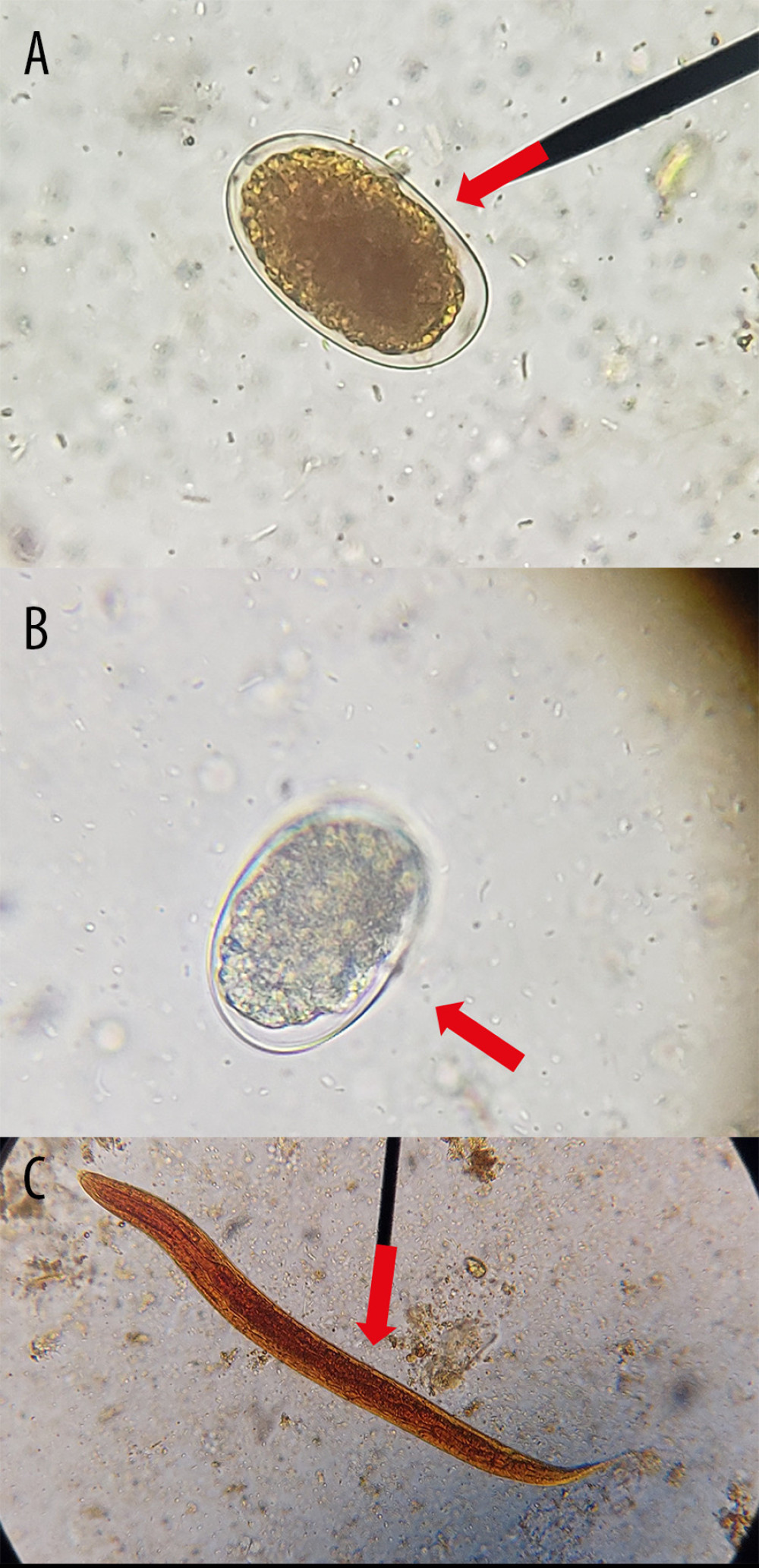

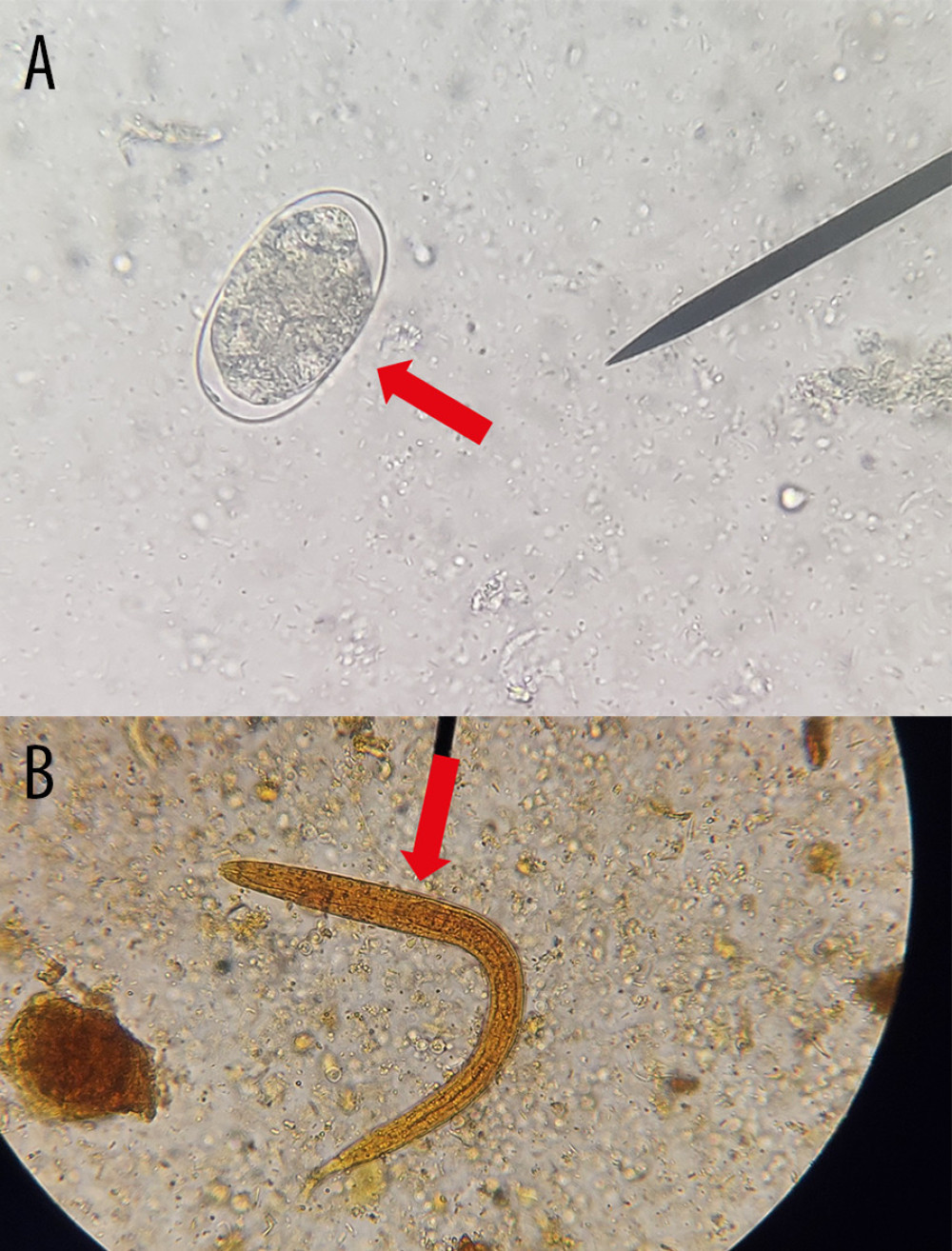

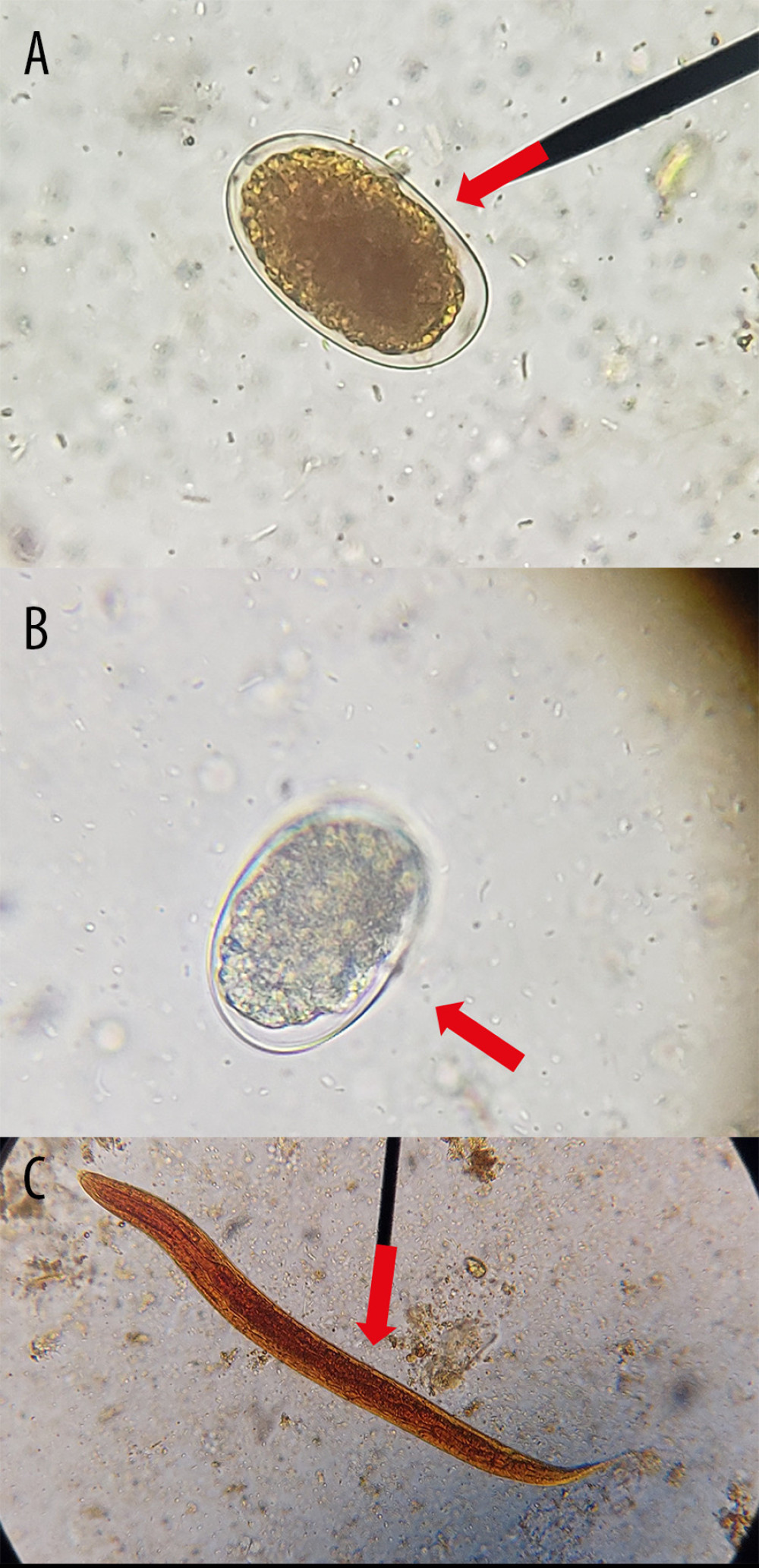

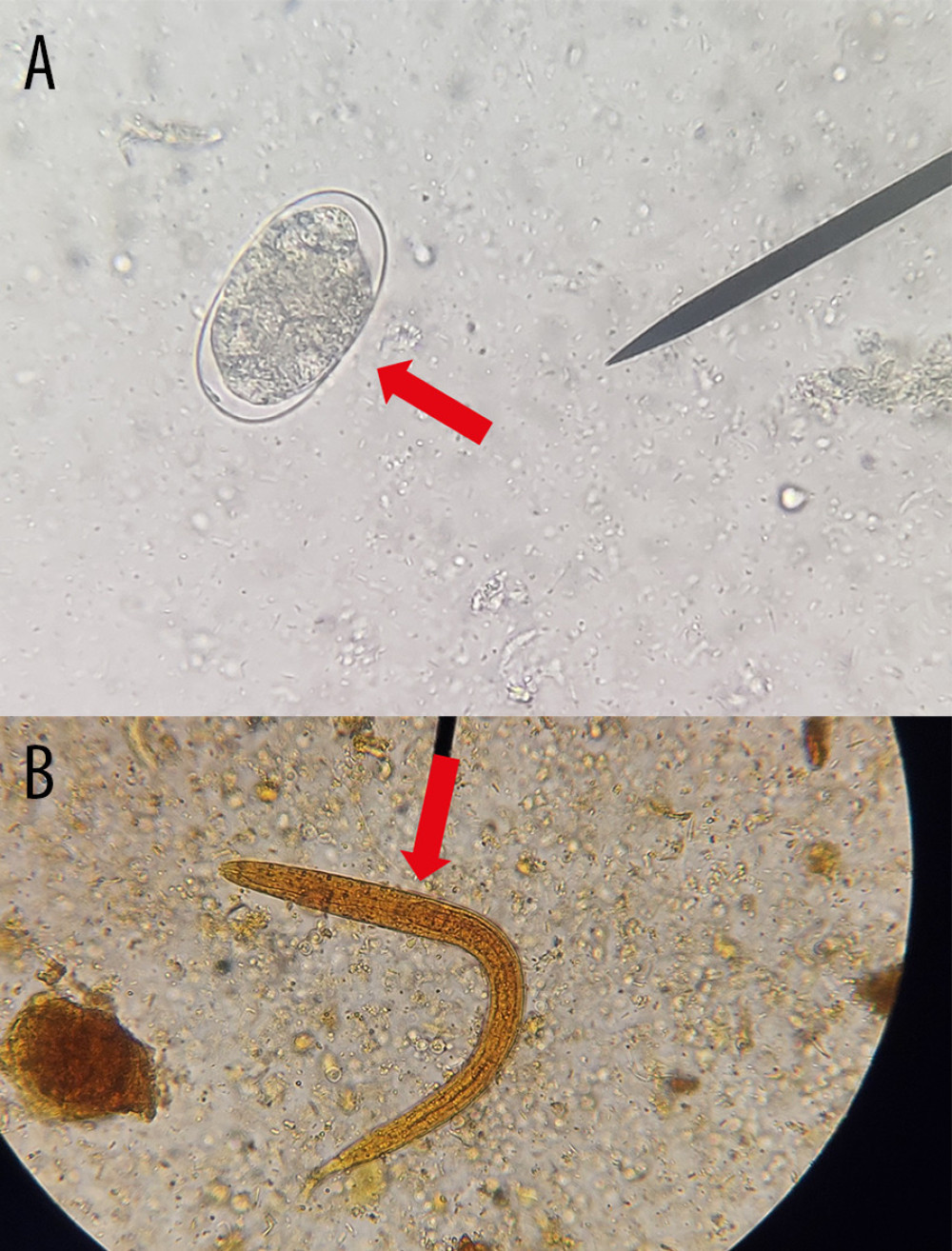

Of the 498 dogs analyzed in the 4 areas studied, 250 (50.20%) were positive for A. caninum (Figure 1), and 41 (8.23%) were positive for Ancylostoma spp. (Figure 2; Table 1). Forty-seven dogs presented vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, decay, weakness, and pale mucous membranes. A total of 9.4% morbidity and 1.2% mortality were observed (6 dogs died).

Regarding the morbidity of domestic dogs with clinical manifestations, when performing stool tests, the bacteria (culture and Gram staining), fungi (AFB and lactophenol staining), and viruses (antigens for parvovirus and canine distemper) were all negative.

Of the 40 synanthropic rodents captured and analyzed, 14 (35%) were identified as Rattus rattus and 26 (65%) as Rattus norvegicus. Of these, 19 (47.5%) were female and 21 (52.5%) were male; furthermore, 24 (60%) weighed more than 250 g, and 16 (40%) weighed less than 250 g. Of the 40 rodents analyzed, only 1 (2.5%) was positive for Ancylostoma caninum (Figure 1; Table 1).

Of the 236 people examined, 3 (1.27%) had cutaneous larva migrans. In the Cooperativa Balerio Estacio sector, 2 cases of CLM were diagnosed (a 13-year-old and a 34-year-old), and in La Ladrillera, 1 case of CLM was diagnosed in a 14-year-old. In these 3 cases, the households had dogs who tested positive for A. caninum (Figure 3; Table 1).

Notably, dogs with ancylostomiasis were orally administered a single dose of 0.5 mg/kg (0.23 mg/lb) milbemycin oxime and praziquantel. After 1 month, the dogs were tested to confirm the absence of the parasite. The 3 people with MCL received oral ivermectin administered as a single dose of 200 μg/kg. Seven days after treatment, skin lesions on the soles of their feet were dry, and they no longer had itching; the symptoms disappeared during the following week [23].

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS:

Of the 236 people who participated in the survey, all had 2 to 6 domestic dogs. The average number of people per household ranged from 5 to 6. The age range was from 2 to 85 years, and the household members had various occupations (22.8% informal trade, 6.1% formal trade, 26.4% dependence, and 44.7%% agriculture). Furthermore, 49% of the people did not wear shoes inside or outside the house; 10% had health insurance (4.4% social insurance and 5.6% farmer insurance). A total of 79.3% of the households studied had houses with mixed construction, and 20.7% had cane wood construction. The areas studied did not have sewerage; various types of water supplies were present (63.7% of the water was drinking water, 33.6% was purchased from a tanker, 2.1% was from the river, and 0.6% was obtained from a deep well). Finally, excreta were disposed of through latrines (30.8%), septic tanks (65.8%) and outdoor locations (3.4%).

ENVIRONMENTAL PARAMETERS:

In the urban-marginal sectors (Balerio Estacio and Ladrillera), the average temperature is 23.54°C to 33.23°C, the humidity is 86.92%, and rainfall occurs mostly in March and April (93.4 to 203 mm), while solar radiation occurs every month for 12 hours and 3 minutes per day. In addition, the climate is tropical savanna, with an overall soil texture of soft clay, although certain sectors are sandy, with a pH between 6.5 (Balerio Estacio) and 6.7 (Ladrillera). In addition, a great variety of animals are present (eg, dogs, cats, birds, rodents, opossums); these areas are deforested due to the growth of the city.

In rural areas (Loma Larga and Santa Rosa), temperatures are between 23.35 and 32.43°C, with 87.99% humidity. Precipitation occurs mostly in March and April (622.5 to 930 mm) and solar radiation occurs every month for 12 hours and 4 minutes per day; the climate is tropical savanna with clay soil, though some areas are sandy; Santa Rosa has a pH of 6, and Loma Larga has a pH of 6.4. Both sites are mostly forested, and the main crops are rice and livestock. There is a great diversity of domestic and wild animals (eg, dogs, cats, birds, pigs, cows, horses, fish, monkeys, rodents, possums, squirrels, and snakes); but some areas are deforested for agricultural purposes.

No significant difference was found in the presence of

Finally, notably, the people and their domestic dogs that participated in the study received the results of their diagnoses. The domestic dogs that had ancylostomiasis were treated and the people who had CLM received expert medical advice for their treatment. In addition, a rodent elimination campaign was implemented.

Discussion

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY:

A greater number of samples, sample size of both domestic dogs, synanthropic rodents and people, and the inclusion of more vulnerable sectors would have improved this research. For example, the areas of Balerio Estacio, Loma Larga, and Santa Rosa could be sampled. On the other hand, during the research the need to measure new sociocultural variables was observed, such as informing people about the presence of the parasite, knowing their habits and customs that can increase the risk of contamination. Regarding coproparasitic methods, the PCR technique could be applied for better identification of the parasite.

Conclusions

Ancylostomiasis is a highly prevalent zoonotic disease in developing countries that can affect the population in endemic areas. In this study, 50.20% of the infections with A.

The following information was collected: social variables through surveys; territorial planning plans for the GADs of the cities of Guayaquil, Nobol and Daule; and environmental parameters through environmental programs (Weather Atlas and Weather Spark), INAMHI meteorological bulletins, GAD land use plans for the cities of Guayaquil, Nobol, and Daule, and through observation. The results obtained suggest that several zoonotic transmissions could occur; however, additional studies are needed to confirm this fact. If such is the case, the community is exposed to significant environmental risk from ancylostomiasis. Therefore, the population should be educated about the sanitary measures needed and about the obligation of periodic deworming of their domestic animals to prevent the transmission of this and other parasites.

Figures

Figure 1. Microscopic identification of (A) egg of Ancylostoma caninum (red arrow) in feces of domestic dogs, (B) egg of Ancylostoma caninum (red arrow) in feces of rodent through the technique of sedimentation by centrifugation using saline solution and (C) larvae of Ancylostoma caninum in feces of domestic dog (red arrow) obtained by the technique of modified Baermann, observed by optical microscopy at 40× and stained/not with Lugol. (Taken by the authors).

Figure 1. Microscopic identification of (A) egg of Ancylostoma caninum (red arrow) in feces of domestic dogs, (B) egg of Ancylostoma caninum (red arrow) in feces of rodent through the technique of sedimentation by centrifugation using saline solution and (C) larvae of Ancylostoma caninum in feces of domestic dog (red arrow) obtained by the technique of modified Baermann, observed by optical microscopy at 40× and stained/not with Lugol. (Taken by the authors).  Figure 2. Microscopic identification of (A) egg of Ancylostoma spp. (red arrow) through the technique of sedimentation by centrifugation using saline solution and (B) larvae of Ancylostoma spp. (red arrow) obtained by the technique of modified Baermann, in the feces of domestic dogs observed by optical microscopy at 40× and stained/not with Lugol. (Taken by the authors).

Figure 2. Microscopic identification of (A) egg of Ancylostoma spp. (red arrow) through the technique of sedimentation by centrifugation using saline solution and (B) larvae of Ancylostoma spp. (red arrow) obtained by the technique of modified Baermann, in the feces of domestic dogs observed by optical microscopy at 40× and stained/not with Lugol. (Taken by the authors).  Figure 3. A 14-year-old boy with a palpable serginous lesion on his right foot was diagnosed with cutaneous larva migrans (MCI). (Taken by the authors).

Figure 3. A 14-year-old boy with a palpable serginous lesion on his right foot was diagnosed with cutaneous larva migrans (MCI). (Taken by the authors). References

1. Banerjee M, Perasso A, Venturino E, Epidemiology and ecoepidemiology: Introducción to the special issue: Math Model Nat Phenom, 2017; 12(2); 1-3

2. Ministry of Tourism from Ecuador (MTE): Ecuador Available from. Updated: 2020https://vivecuador.com/html2/esp/ministerio.htm

3. Aziz MH, Ramphul K, Ancylostoma: StatPearls Jun, 2024 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507898/

4. Mirisho R, Neizer M, Sarfo B, Prevalence of intestinal helminths infestation in children attending Princess Marie Louise Children’s Hospital in Accra, Ghana: J Parasitol Res, 2017; 2017; 8524985

5. Wongwigkan J, Inpankaew T, Semi-domesticated dogs as a potential reservoir for zoonotic hookworms in Bangkok, Thailand: Vet World, 2020; 13(5); 909-15

6. Massetti L, Wiethoelter A, McDonagh P, Faecal prevalence, distribution and risk factors associated with canine soil-transmitted helminths contaminating urban parks across Australia: Int J Parasitol, 2022; 52(10); 637-46

7. Maxfield L, Crane JS, Cutaneous larva migrans: StatPearls Jun, 2024 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507706/

8. Brahmbhatt N, Patel P, Hasnani J, Study on prevalence of ancylostomosis in dogs at Anand district, Gujarat, India: Vet World, 2015; 8(12); 1405-9

9. Carrera-Játiva PD, Torres C, Figueroa F, Gastrointestinal parasites in wild rodents in Chiloé Island-Chile: Braz J Vet Parasitol, 2023; 32(1); e017022

10. Kladkempetch D, Tangtrongsup S, Tiwananthagorn S: Asian Countries. Animals, 2020; 10(1); 2154

11. Almeida R, Bonilla C[Prevalence of in domestic dogs of the San Luís and Velasco parishes of the Riobamba canton] [December 2015– 2016 May, 2023 Available from: [in Spanish]https://repositorio.uta.edu.ec/jspui/handle/123456789/19921

12. Giraldo MI, García NL, Castaño JC, Prevalence of intestinal helminths in canines in the department of Quindío: Biomédica, 2005; 25(3); 346-52 [in Spanish]

13. Bowman D: Georgis parasitology for veterinarians, 2012, Barcelona-España, ELSEVIER in Spanish

14. Botero D, Restrepo M: Human parasites, 2019, Medellín-Colombia, Corporation for Biological Research [in Spanish]

15. Romero Cabello R, 2019 Human microbiology and parasitology: Etiological bases of infectious and parasitic diseases, 2019, México DF, Panamericana [in Spanish]

16. Weather Spark: The weather throughout the year anywhere in the world. Weather reports with weather by month, day and even hour, 2023 Available from: https://es.weatherspark.com/

17. Weather Atlas: Weather forecasts and weather forecast information Available from: https://www.weather-atlas.com/es

18. Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology (INAMHI): Meteorological Bulletins Available from: https://www.inamhi.gob.ec/boletines-meteorologicos/

19. Official Gazette # 37: Guayaquil Territorial Development and Planning Plan, Municipal Decentralized Autonomous Government of Guayaquil Available from: https://www.guayaquil.gob.ec/document/periodo-2019-2023-gaceta-oficial-37/

20. : Nobol Territorial Development and Planning Plan, Municipal Decentralized Autonomous Government of the city of Nobol Available from: https://www.nobol.gob.ec/web/rendiciondecuentas2021/PDOT_Nobol_2020-2027.pdf

21. : Daule Territorial Development and Planning Plan, Municipal Decentralized Autonomous Government of Daule Available in: https://www.daule.gob.ec/planes/

22. Dubie T, Sire S, Fentahun G, Bizuayehu F, Prevalence of gastrointestinal helminths of dogs and associated factors in Hawassa City of Sidama Region, Ethiopia: J Parasitol Res, 2023; 2023; 6155741

23. Coello R, Pazmiño B, Reyes E, A case of cutaneous larva migrans in a child from Vinces, Ecuador: Am J Case Rep, 2019; 20(1); 1402-6

24. De Sotomayor R, Serrano E, Tantaleán M, Identification of gastrointestinal parasites in rats from Metropolitan Lima: Rev Inv Vet Perú, 2015; 26(2); 273-81 [in Spanish]

25. Lucio A, Liotta JL, Yaros JP: J Parasitol, 2012; 98(5); 1041-44

26. Massetti L, Colella V, Zendejas PA, High-throughput multiplex qPCRs for the surveillance of zoonotic species of canine hookworms: PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2020; 14(6); e0008392

27. Dourado W, Talamini A, De Carvalho J, Dourado N, Saraiva K, Occurrence of Ancylostoma in dogs, cats and public places from Andradina city, São Paulo state, Brazil: Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo, 2011; 53(4); 181-84

28. Silva V, Silva J, Gonçalves M, Epidemiological survey on intestinal helminths of stray dogs in Guimarães, Portugal: J Parasit Dis, 2020; 44(4); 869-76

29. Pratap R, Chandra B, Begum N, Talukder H, Prevalence of hookworm infections among stray dogs and molecular identification of hookworm species for the first time in Bangladesh: Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports, 2022; 30(1); 100719

30. Idrissi H, El Hamiani S, Duchateau L, Prevalence, risk factors and zoonotic potential of intestinal parasites in dogs from four locations in Morocco: Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports, 2022; 34(1); 100775

31. Mukaratirwa S, Singh V, Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites of stray dogs impounded by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA), Durban and Coast, South Africa: J S Afr Vet, 2010; 81(2); 123-25

32. Moreno-Cadena D, Mena-Pérez R, Quisirumbay-Gaibor J, Comparative study of endoparasitosis in canines in two localities of the Ecuadorian coast: Rev Electron Vet, 2018; 19(6); 1-11

33. Encalada-Mena LA, Duarte-Ubaldo EI, Vargaz-Magaña JJ, Prevalence of gastroenteric parasites of dogs in the city of Escárcega, Campeche, México: Univ y Ciencia, Trópico Húmedo, 2011; 27(2); 209-17

34. Calvopiña M, Cabezas M, Cisneros E, Diversity and prevalence of gastrointestinal helminths of free-roaming dogs on coastal beaches in Ecuador: Potential for zoonotic transmission: Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports, 2023; 40; 100859

35. Kagira J, Kanyari P, Parasitic diseases as causes of mortality in dogs in Kenya: A retrospective study of 351 cases (1984–1998): Israel J Vet Med, 2000; 56(1); 1-4

36. Loukas A, Hotez P, Diemert D, Hookworm infection: Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016; 2; 16088

37. Naupay A, Castro J, Tello M: Vet Perú, 2019; 30(1); 320-29 [in Spanish]

38. Frederick R, Abdul-Mawah S, The prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in wild rats (muridae) in pilajau oil palm plantation of Sawit Kinabalu Group, Membakut Sabah Malaysia/Richel Natasha Frederick and Siti Sarayati Abdul-Mawah: Borneo Akademika, 2022; 6(2); 12-21

39. Lucio CD, Gentile R, Cardoso TD, Composition and structure of the helminth community of rodents in matrix habitat areas of the Atlantic forest of southeastern Brazil: Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl, 2021; 15(1); 278-79

40. Sears WJ, Cardenas J, Kubofcik J: Ecuador Emerg Infect Dis, 2022; 28(9); 1867-69

41. Suarez PAnalysis of the spatial distribution of larva migrans in Ecuador, using classic epidemiological indicators with data from the National Health Registry for the period 2007-2017 February, 2024 Available from: URL: [in Spanish]https://dspace.udla.edu.ec/handle/33000/12025

42. Rivero MR, De Angelo C, Nuñez P, Environmental and socio-demographic individual, family and neighborhood factors associated with children intestinal parasitoses at Iguazú, in the subtropical northern border of Argentina: PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2017; 11(11); e0006098

43. Elfu Feleke B, Epidemiology of hookworm infection in the school-age children: A comparative cross-sectional study: Iran j Parasitol, 2018; 13(4); 560-66

44. Dhaka R, Verma R, Parmar A, Association between the socioeconomic determinants and soil-transmitted helminthiasis among school-going children in a rural area of Haryana: J Family Med Prim Care, 2020; 9(7); 3712-15

45. Tiruneh T, Geshere G, Ketema T, Prevalence and determinants of soil-transmitted helminthic infections among school children at Goro Primary School, South West Shewa, Ethiopia: Int J Pediatr, 2020; 2020; 8612054

46. Seguel M, Gottdenker N, The diversity and impact of hookworm infections in wildlife: Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl, 2017; 6(3); 177-94

47. Riess H, Clowes P, Kroidl I, Hookworm infection and environmental factors in Mbeya region, Tanzania: A cross-sectional, population-based study: PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2013; 7(9); e2408

48. Li R, Gao J, Gao L, Lu Y, A half-century studies on epidemiological features of ancylostomiasis in China: A review article: Iran J Public Health, 2019; 48(9); 1555-65

49. Van Dijk J, Louw M, Kalis L, Ultraviolet light increases mortality of nematode larvae and can explain patterns of larval availability at pasture: Int J Parasitol, 2009; 39(10); 1151-56

50. Kiene F, Andriatsitohaina B, Ramsay MS, Habitat fragmentation and vegetation structure impact gastrointestinal parasites of small mammalian hosts in Madagascar: Ecol Evol, 2021; 11(11); 6766-88

51. Anegagrie M, Lanfri S, Aramendia AA, Environmental characteristics around the household and their association with hookworm infection in rural communities from Bahir Dar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2021; 15(6); e0009466

Figures

Figure 1. Microscopic identification of (A) egg of Ancylostoma caninum (red arrow) in feces of domestic dogs, (B) egg of Ancylostoma caninum (red arrow) in feces of rodent through the technique of sedimentation by centrifugation using saline solution and (C) larvae of Ancylostoma caninum in feces of domestic dog (red arrow) obtained by the technique of modified Baermann, observed by optical microscopy at 40× and stained/not with Lugol. (Taken by the authors).

Figure 1. Microscopic identification of (A) egg of Ancylostoma caninum (red arrow) in feces of domestic dogs, (B) egg of Ancylostoma caninum (red arrow) in feces of rodent through the technique of sedimentation by centrifugation using saline solution and (C) larvae of Ancylostoma caninum in feces of domestic dog (red arrow) obtained by the technique of modified Baermann, observed by optical microscopy at 40× and stained/not with Lugol. (Taken by the authors). Figure 2. Microscopic identification of (A) egg of Ancylostoma spp. (red arrow) through the technique of sedimentation by centrifugation using saline solution and (B) larvae of Ancylostoma spp. (red arrow) obtained by the technique of modified Baermann, in the feces of domestic dogs observed by optical microscopy at 40× and stained/not with Lugol. (Taken by the authors).

Figure 2. Microscopic identification of (A) egg of Ancylostoma spp. (red arrow) through the technique of sedimentation by centrifugation using saline solution and (B) larvae of Ancylostoma spp. (red arrow) obtained by the technique of modified Baermann, in the feces of domestic dogs observed by optical microscopy at 40× and stained/not with Lugol. (Taken by the authors). Figure 3. A 14-year-old boy with a palpable serginous lesion on his right foot was diagnosed with cutaneous larva migrans (MCI). (Taken by the authors).

Figure 3. A 14-year-old boy with a palpable serginous lesion on his right foot was diagnosed with cutaneous larva migrans (MCI). (Taken by the authors). Tables

Table 1. Prevalence of ancylostomiasis in domestic dogs and synanthropic rodents and presence of CLM in people in urban-marginal and rural sectors of the Ecuadorian coast.

Table 1. Prevalence of ancylostomiasis in domestic dogs and synanthropic rodents and presence of CLM in people in urban-marginal and rural sectors of the Ecuadorian coast. Table 1. Prevalence of ancylostomiasis in domestic dogs and synanthropic rodents and presence of CLM in people in urban-marginal and rural sectors of the Ecuadorian coast.

Table 1. Prevalence of ancylostomiasis in domestic dogs and synanthropic rodents and presence of CLM in people in urban-marginal and rural sectors of the Ecuadorian coast. In Press

12 Mar 2024 : Database Analysis

Risk Factors of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Population-Based Study: Results from SHIP-TREND-1 (St...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943140

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Preoperative Blood Transfusion Requirements for Hemorrhoidal Severe Anemia: A Retrospective Study of 128 Pa...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943126

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) and 3 (TIMP-3) as New Markers of Acute Kidney Injury Afte...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943500

12 Mar 2024 : Review article

Optimizing Behçet Uveitis Management: A Review of Personalized Immunosuppressive StrategiesMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943240

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952