07 March 2022: Clinical Research

Comparison of Outcomes Following General Anesthesia and Spinal Anesthesia During Emergency Cervical Cerclage in Singleton Pregnant Women in the Second Trimester at a Single Center

Yan Wang12BCEF, Xiaoli Ning2BF, Yue Yu2AB, Xiaoqiong Xia2BC, Wei Wang3C*, Xianwen Hu1AGDOI: 10.12659/MSM.934771

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e934771

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Little information exists regarding the best anesthesia method for emergency cerclage. This single-center study aimed to compare the outcomes following general anesthesia and spinal anesthesia during emergency cervical cerclage in women in the second trimester of a singleton pregnancy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: A total of 297 pregnant patients were recruited: 141 patients were assigned to the general anesthesia group and 156 patients were assigned to the spinal anesthesia group. Periprocedural data and obstetric outcomes were recorded and statistically analyzed.

RESULTS: Average duration of the cerclage procedure was shorter in the general anesthesia group than in the spinal anesthesia group (25.78±9.4 min versus 30.88±10.5 min; P<0.05). No severe maternal complications, such as hematosepsis or maternal death, occurred after the procedure for either group. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and C-reactive protein (CRP) increased after emergency cerclage in both groups, but at no time did the 2 groups differ significantly (P>0.05). There was also no significant difference in the incidence of miscarriage or preterm delivery (delivery <34 gestational weeks) or in neonatal outcome between the 2 groups (P>0.05).

CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study showed that there were no significant differences in maternal and neonatal outcomes, rates of miscarriage, or preterm delivery between general anesthesia and spinal anesthesia during emergency cervical cerclage in women in the second trimester of a singleton pregnancy.

Keywords: Anesthetics, General, Cerclage, Cervical, Uterine Cervical Incompetence, Adult, Anesthesia, Spinal, Emergencies, Female, Humans, Pregnancy, Pregnancy Trimester, Second

Background

Cervical incompetence was first noted by Green in the journal Lancet in 1865 [1]. It is defined as the inability to maintain a pregnancy because of structural and functional weakness in the cervix. Typical clinical symptoms include painless cervical dilation and bulging fetal membranes in the second trimester (typically between the 18th and 22nd weeks) in the absence of uterine contractions. Scholars have reported that cervical incompetence occurs in about 1% of all pregnancies and accounts for 8% of late-term miscarriages and preterm births [2]. It also brings about profound social and family problems. In singleton pregnancy cases with cervical dilation and bulging fetal membranes in the second trimester, emergency cervical cerclage is the primary treatment for extending the pregnancy period [3]. For case screening, patients with suspected infection or signs of contraction should be strictly excluded [4]. The literature suggests that emergency cervical cerclage can increase the newborn survival percentage to 46–100% [5]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 clinical studies [6] reported that in cases with advanced dilation (1–5 cm), emergency cervical cerclage increased neonatal survival compared to the control group.

Emergency cerclage can be performed transvaginally with the McDonald and Shirodkar methods; of these 2 methods, the McDonald type is more widely used because it is easier to perform [7,8]. The operation duration is typically less than 30 min. The degree of patient cervical dilation before the operation influences anesthesia options. If the patient has not developed signs of advanced cervical dilation, several anesthesia methods can be used, including spinal anesthesia, epidural anesthesia, and general anesthesia [9]. However, if the patient has advanced cervical dilation or bulging fetal membranes, the choice of anesthesia method may be critical. Spinal anesthesia can quickly prevent pain, but the control of the anesthesia plane has a marked effect on the difficulty of operation, the patient’s vital signs, and subjective feelings. Meanwhile, unstable halogenated alkaline inhalation general anesthesia can relax the smooth muscles of the uterus, reduce uterine pressure, prevent further complicating the operation, and reduce the risk of premature rupture [10]. Ioscovich et al [10] identified cases of prophylactic cervical cerclage under general anesthesia and regional anesthesia and found the maternal-fetal prognosis was similar in both groups. To date, however, there have been few reports on anesthetic methods for emergency cervical cerclage; therefore, authoritative guidance is lacking.

Inflammatory reactions after emergency cervical cerclage are associated with poor outcomes. Recent studies [11,12] have reported that the presence of factors associated with inflammation in the peripheral blood and amniotic fluid of pregnant women can reveal systemic inflammatory responses that may be predictors of preterm labor. Jung et al [13] identified neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios in maternal peripheral blood and interleukin 8 levels in amniotic fluid as important predictors of outcome after emergency cervical cerclage. A combination of these inflammatory factors may be effective in identifying the risk of spontaneous abortion and preterm labor after cerclage and thus may serve as a basis by which clinicians can evaluate the prognosis of patients undergoing emergency cervical cerclage.

This single-center study aimed to compare the outcomes following general anesthesia and spinal anesthesia during emergency cervical cerclage in women in the second trimester of singleton pregnancy. Surgical parameters, perioperative blood inflammation factors, uterine contraction, and obstetric outcome of patients were recorded and analyzed. Based on our findings, we discuss the optimal anesthetic method for clinical practice, hoping to improve clinical outcomes and provide a standardized diagnosis and treatment routine for obstetricians and gynecologists.

Material and Methods

PARTICIPANTS:

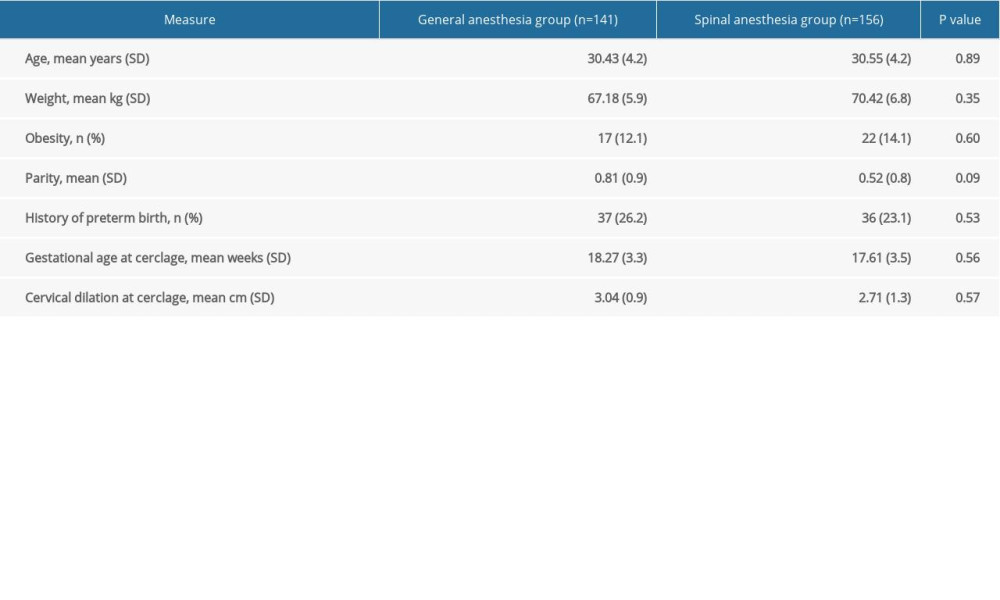

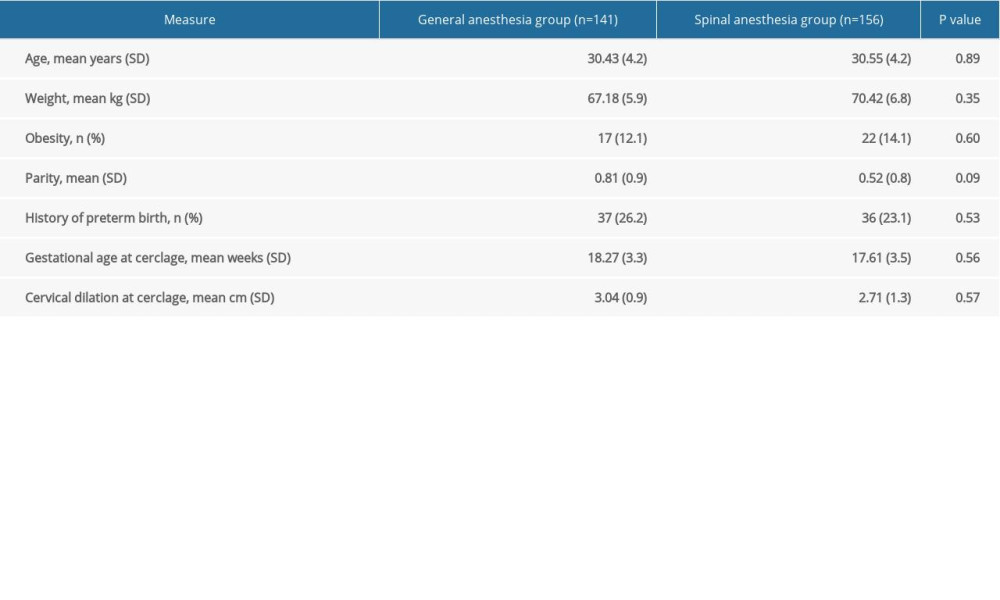

This case-control research included 306 consecutive patients who underwent emergency cervical cerclage following a diagnosis of cervical incompetence at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of Chaohu Hospital, Anhui Medical University, between December 2014 and December 2020. Nine cases were lost to follow-up (3 in the general anesthetic group and 6 in the spinal anesthetic group), for a total of 297 cases enrolled. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Chaohu Hospital, Anhui Medical University. The inclusion criteria were as follows: singleton pregnant women at 14–24 weeks of gestation, cervical tube length ≤15 mm as determined by ultrasound, advanced cervical dilation (1–5 cm), no contractions, no vaginal bleeding, and no inflammatory indicators. The average age was 30.51±4.2 years, and of the 297 pregnant women, 73 women had a history of miscarriage or preterm delivery (delivery <34 gestational weeks). Patients with neurological disorders or back pain were excluded. After patients signed an informed consent form, they were assigned to 1 of 2 groups, based on a comprehensive assessment of the surgeon and anesthesiologist. The criteria used for assignment were as follows: Patients with abnormal blood clotting, a platelet count less than 50 000/μL, scoliosis, and patients who refused spinal anesthesia were assigned to the general anesthetic group, and the remaining patients were assigned to the spinal anesthetic group. Characteristics and clinical data for the study population are listed in Table 1.

ANESTHESIA PROCESS AND SURGICAL METHOD:

In the spinal anesthesia group, after entering the operating room, the patient was hydrated with 500 ml of sodium lactate Ringer’s solution and positioned on their left side. Using a Braun lumbar puncture bag, a spinal anesthetic was placed at the L3–4 interspace, the subarachnoid space was punctured with a 21-gauge Sprotte needle, and an injection of 2.5 ml of 0.5% ropivacaine plus 3% glucose was administered. The patient was positioned supine immediately after successful anesthesia. In the general anesthesia group, general anesthesia was sequentially induced using 20 μg sufentanil, 2.5 mg/kg propofol, and 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium, with maintenance of inhalation of 1.0 MAC sevoflurane. A laryngeal mask airway was used. The patient was allowed to wake up naturally after surgery.

Emergency cervical cerclage was performed using McDonald’s technique by 1 of 2 director doctors with at least 5 years of experience in cervical cerclage. Double 10 silk thread was used to suture the patient’s cervix. All patients were given prophylactic antibiotics (second-generation cephalosporins) and tocolytics (nifedipine) during and after cerclage for at least 3 days.

OBSERVED INDICATORS:

We recorded and statistically analyzed the operation time, restoration time in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), the general condition of the patient, and any adverse reactions such as nausea or vomiting. We also checked participants for contractions twice daily for 30 min between 8: 00 and 16: 00 using a fetal heart monitor for 3 days after cerclage. If there were 3 or more contractions within 30 min, patients were considered to have increased uterine contraction. Intravenous blood samples were taken 24 h before cerclage and 24 h after the operation to measure the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and CRP levels. Data on delivery week and neonatal outcomes were gathered from medical records.

STATISTICAL METHODS:

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 18.0 software. The data are presented as the number, percentage, or mean±SD. Continuous data were analyzed using the

Results

Pregnant women in each treatment group were similar in age, weight, obesity, parity, history of preterm birth, and gestation age at cerclage; there was also no difference in cervical dilation status at cerclage (Table 1).

Mean surgery time was shorter in the general anesthetic group than in the spinal anesthetic group (25.78±9.4 and 30.88±10.5 min, respectively;

Perioperative blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios and CRP levels increased significantly after emergency cerclage in both groups. However, there were no significant differences between the groups in these levels at any time (Table 3).

A comparison of pregnancy outcomes in the 2 groups of patients is presented in Table 4. The average delivery week of pregnant women was 32.5±4.2 weeks in the general anesthetic group and 31.0±4.9 weeks in the spinal group. Rate of delivery before 34 gestation weeks was 43.3% in the general anesthetic group and 42.3% in the spinal group. The neonatal survival rates in the general anesthetic group and spinal group were 70.2% and 73.1%, respectively. These pregnancy outcomes did not differ significantly between the 2 groups of patients (Table 4).

Discussion

The efficacy and safety of emergency cervical cerclage remain controversial [14–16], and limited information exists regarding the best anesthesia method for emergency cerclage. The results of this study showed that both general and spinal anesthesia can be safely used for emergency cerclage procedures. Our results are in agreement with previous reports [9,10]. We believe the 70.2% and 73.1% newborn survival rates achieved in the general anesthetic and spinal group, respectively, is a good result. Neither anesthesia method for emergency cerclage promoted contractions, and the incidence of miscarriage or preterm labor, as well as newborn survival rate, did differ significantly between the 2 groups.

Anesthesia technique is an important factor that affects the difficulty of the operation, the patient’s vital signs, subjective feelings, and prognosis. Among pregnant women, the anesthesia method can affect both the woman and the fetus. Choice of anesthetic methods for pregnant women must consider maintaining airway stability, reducing the possible toxicity and adverse effects of the drug on the fetus, and the safety of aspiration prevention and airway management, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, making regional anesthesia preferred whenever possible [16–19]. However, emergency cervical cerclage is distinct, as it is a minor gynecological procedure; the average duration of suturing the cervix is less than half an hour. Crucially, this operation is the most effective way to save a fetus from miscarriage and prolong the gestation age for a pregnant woman in the second trimester. The practice of using regional anesthesia whenever possible is not quite applicable for emergency cervical cerclage [10]. However, to date, there is very little information regarding the best anesthesia method for emergency cerclage.

Fetal susceptibility to teratogenic drug effects is highest at 6–12 weeks of gestation, yet aspiration prophylaxis should be performed at 12–20 weeks of gestation, making general anesthesia relevant for emergency cerclage in this period (12–20 weeks of gestation) [17,20–22]. In a retrospective study, Ioscovich et al [10] identified 487 cases of cervical cerclage and showed that both regional and general anesthesia were safe for performing cervical cerclage. However, the study was not designed to assess the risk of exposure of the fetus to general anesthetic drugs. Ing et al [23] evaluated a cohort of 2024 children and found that prenatal exposure to general anesthetics is associated with increased externalizing behavioral problems in childhood. They also question whether only children exposed in the third trimester can be at risk of long-term neurodevelopmental effects. More rigorous prospective random controlled trials and multicenter studies are still needed. Some scholars believe that the stress associated with tracheal intubation increases contractions, which can induce spontaneous abortion, the very thing cerclage aims to prevent [10]. However, whether general anesthesia increases the risk of contraction and abortion is controversial [22,24]. Yoon et al [24] found that pregnant patients who underwent laparoscopic adnexal mass surgery with regional anesthesia were at greater risk of preterm labor than patients who underwent general anesthesia. Yoon next designed a prospective randomized controlled study of general anesthesia and spinal anesthesia for elective cerclage in the second trimester and found that anesthetic methods performed for elective cerclage did not affect perioperative changes in plasma oxytocin or postoperative uterine contraction. Our study is the first to explore the choice of anesthetic methods for emergency cervical cerclage. The preoperative cervical dilation of the enrolled patients was 1–5 cm, and nifedipine was routinely used as a tocolytic agent after surgery. Increased contraction was observed in 62 patients (44.0%) in the general anesthetic group and 79 cases (50.6%) in the spinal anesthetic group. However, these symptoms disappeared after 1–2 days with routine tocolytic agent. There was also no significant difference in the incidence of miscarriage or preterm delivery between the 2 groups.

In this study, we observed a significantly greater drop in the systolic pressure of patients in the spinal anesthesia group, which could lead to insufficient placental blood perfusion. By contrast, an increase in abdominal pressure due to patients’ nausea and vomiting can increase the difficulty and extend the operation time. We also confirmed that the general anesthetic group had shorter surgery times than the spinal anesthetic group (25.78±9.4 and 30.88±10.5 min,

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess perioperative blood inflammation factors among patients undergoing emergency cerclage operation with different methods of anesthesia. It is a prevailing view in academic circles that subclinical intra-amniotic infection is a predictor of adverse outcomes of emergency cerclage, and that extra-amniotic inflammation is significantly related to preterm labor at less than 32 weeks after emergency cerclage [11,12]. The ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes in plasma is associated with uterine hyperactivity and spontaneous preterm birth after cerclage [13]. Zhu et al [3] found that the CRP level and white blood cell (WBC) counts can reflect subclinical or clinical chorioamnionitis with great sensitivity. CRP and WBC counts increased significantly in the failed emergency cerclage patients and may be associated with microbial infection when replacing the bulging membranes into the uterus during cerclage [3]. For our study, we performed rigorous screening to exclude suspected cases of infection before operation, and the patients were treated with second-generation cephalosporins routinely during and after cerclage for at least 3 days. Measuring neutrophil-lymphocyte concentration ratio and CRP level, we found that the inflammation factors increased significantly after emergency cerclage in both groups. However, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups at any time. There was no evidence of clinical infection, but a postoperative stress response cannot be ruled out. Follow-up studies should further increase the testing time and sample size and add infection indicators such as WBC counts and interleukin 6/8 infection indicators in the peripheral blood and amniotic water to investigate the impact of different anesthesia methods on infection and associated outcomes of gestation.

There are some limitations to this study. The patients in this study were assigned different anesthetics based on the assessment and judgment of the surgeon and anesthesiologist. For ethical issues, only non-randomized studies of general anesthesia versus spinal anesthesia for emergency cerclage operation have been performed to date. All enrolled patients were emergency department patients who had McDonald’s cerclage technique performed by the same 2 director doctors. However, dilation degree of the cervix before operation and location of the silk thread in the cerclage could lead to differences in duration of surgery, subjective feelings of patients after the operation, and the success rate of the emergency cerclage. More rigorous prospective random controlled trials and multicenter studies are still needed. The effects of anesthesia on fetal fibrosis protein in amniotic fluid, vaginal secretions, prostaglandin F2α levels, and contractions and maternal outcomes all need to be explored. This will provide better guidance for improving long-term pregnancy outcomes for emergency cerclage.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that there were no significant differences in maternal and neonatal outcomes, rates of miscarriage, or preterm delivery between general anesthesia and spinal anesthesia during emergency cervical cerclage in women in the second trimester of a singleton pregnancy. We hope that our findings can improve clinical outcomes of patients who underwent an emergency cerclage operation and provide high-level clinical evidence for obstetricians and gynecologists.

Tables

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the study population. Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes between women who received general anesthesia and those who received spinal anesthesia for emergency cervical cerclage.

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes between women who received general anesthesia and those who received spinal anesthesia for emergency cervical cerclage. Table 3. Perioperative blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios and C-reactive protein levels (mg/l) before and after cervical cerclage.

Table 3. Perioperative blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios and C-reactive protein levels (mg/l) before and after cervical cerclage. Table 4. Neonatal outcomes of emergency cerclage.

Table 4. Neonatal outcomes of emergency cerclage.

References

1. Grant A: Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth, 1989, New York, Oxford University Press

2. Debbs RH, Chen J, Contemporary use of cerclage in pregnancy: Clin Obstet Gynecol, 2009; 52(4); 597-610

3. Zhu LQ, Chen H, Chen LB, Effects of emergency cervical cerclage on pregnancy outcome: A retrospective study of 158 cases: Med Sci Monit, 2015; 21; 1395-401

4. Mönckeberg M, Valdés R, Kusanovic JP, Patients with acute cervical insufficiency without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation treated with cerclage have a good prognosis: J Perinat Med, 2019; 47(5); 500-9

5. Naqvi M, Barth WH, Emergency cerclage: Outcomes, patient selection, and operative considerations: Clin Obstet Gynecol, 2016; 59(2); 286-94

6. Ehsanipoor RM, Seligman NS, Saccone G, Physical examination-indicated cerclage: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Obstet Gynecol, 2015; 126(1); 125-35

7. Wood SL, Owen J, Cerclage: Shirodkar, McDonald, and modifications: Clin Obstet Gynecol, 2016; 59(2); 302-10

8. Alper B, Ozan D, A comparison of emergency and therapeutic modified Shirodkar cerclage: An analysis of 38 consecutive cases: Turk J Obstet Gynecol, 2019; 16(1); 1-6

9. Berghella V, Ludmir J, Simonazzi G, Owen J, Transvaginal cervical cerclage: Evidence for perioperative management strategies: Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2013; 209(3); 181-92

10. Ioscovich A, Popov A, Gimelfarb Y, Anesthetic management of prophylactic cervical cerclage: A retrospective multicenter cohort study: Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2015; 291(3); 509-12

11. Jain V, Inflammatory markers and selective cervical cerclage: Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2007; 196(1); e32 author reply e-32–33

12. Lee J, Lee JE, Choi JW, Proteomic analysis of amniotic fluid proteins for predicting the outcome of emergency cerclage in women with cervical insufficiency: Reprod Sci, 2020; 27(6); 1318-29

13. Jung EY, Park KH, Lee SY, Predicting outcomes of emergency cerclage in women with cervical insufficiency using inflammatory markers in maternal blood and amniotic fluid: Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2016; 132(2); 165-69

14. Rand L, Norwitz ER, Current controversies in cervical cerclage: Semin Perinatol, 2003; 27(1); 73-85

15. Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Hummel P, van Geijn HP, Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial: Emergency cerclage with bed rest versus bed rest alone: Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2003; 189(4); 907-10

16. Daskalakis G, Papantoniou N, Mesogitis S, Antsaklis A, Management of cervical insufficiency and bulging fetal membranes: Obstet Gynecol, 2006; 107(2 Pt 1); 221-26

17. Van De Velde M, De Buck F, Anesthesia for non-obstetric surgery in the pregnant patient: Minerva Anestesiol, 2007; 73(4); 235-40

18. Reitman E, Flood P, Anaesthetic considerations for non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy: Br J Anaesth, 2011; 107(Suppl 1); i72-78

19. Ravi SS, Aditya PM, Ajit K, Management of obstetric analgesia in the developing countries during the coronavirus disease pandemic: A narrative review: Anesth Essays Res, 2020; 14(4); 545-49

20. : Clinical anesthesia, 2009, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

21. Chestnut D: Obstetric anesthesia: Principles and practice, 2004, Mosby

22. Lee A, Shatil B, Landau R, Intrathecal 2-chloroprocaine 3% versus hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.75% for cervical cerclage: A double-blind randomized controlled trial: Anesth Analg, 2021 [Online ahead of print]

23. Ing C, Landau R, DeStephano D, Prenatal exposure to general anesthesia and childhood behavioral deficit: Anesth Analg, 2021; 133(3); 595-605

24. Yoon HJ, Hong JY, Kim SM, The effect of anesthetic method for prophylactic cervical cerclage on plasma oxytocin: a randomized trial: Int J Obstet Anesth, 2008; 17(1); 26-30

Tables

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the study population.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the study population. Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes between women who received general anesthesia and those who received spinal anesthesia for emergency cervical cerclage.

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes between women who received general anesthesia and those who received spinal anesthesia for emergency cervical cerclage. Table 3. Perioperative blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios and C-reactive protein levels (mg/l) before and after cervical cerclage.

Table 3. Perioperative blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios and C-reactive protein levels (mg/l) before and after cervical cerclage. Table 4. Neonatal outcomes of emergency cerclage.

Table 4. Neonatal outcomes of emergency cerclage. In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variation of Medical Comorbidities in Oral Surgery Patients: A Retrospective Study at Jazan ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943884

08 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Evaluation of Foot Structure in Preschool Children Based on Body MassMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943765

15 Apr 2024 : Laboratory Research

The Role of Copper-Induced M2 Macrophage Polarization in Protecting Cartilage Matrix in OsteoarthritisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943738

07 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 179 Male Third- and Fourt...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943468

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952