26 July 2023: Database Analysis

Unveiling the Hidden Burden: Mapping the Landscape of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome Research. A Bibliometric Study and Visualization Analysis

Xiayahu Li1ABF, Yaolin Li2ACDE*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.939661

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e939661

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) has become a major concern for patients and their families due to the rising number of ICU admissions. We conducted a bibliometric analysis to identify hotspots and trends in PICS research.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: We searched for PICS-related publications in the Web of Science Core Collection up to May 1, 2022. We used CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Scimago Graphica to analyze collaboration among countries, institutions, and authors, and to identify research hotspots and frontiers.

RESULTS: Our analysis included 294 research papers on PICS, with the United States leading the field with 146 published papers. Collaboration among institutions and authors was active mainly in the Americas, Europe, and Australia. Highly cited researchers were members of the Outcomes After Critical Illness and Surgery (OACIS) Group, with Ramona O Hopkins as the most published author. Research topics focused on septic shock, COVID-19, qualitative research, and rehabilitation, with publications primarily in critical care medicine journals. Keyword analysis revealed that the main research focus included stress disorders, quality of life, mechanical ventilation, acute lung injury, risk factors, and descriptive studies during hospitalization.

CONCLUSIONS: PICS research is limited, focusing primarily on short-term clinical effects and lacking long-term prognostic observations and multinational studies. Increased collaboration among countries and regions is necessary to advance research in this field. Hotspots in research focus on prognosis and an integrated approach to management.

Keywords: Bibliometrics, Data Visualization, Postintensive Care Syndrome, Humans, COVID-19, Critical Illness, Quality of Life

Background

Post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) refers to a long-term functional impairment that affects patients who have been in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). This syndrome includes physical, cognitive, and psychiatric impairments, with more than half of surviving patients experiencing at least 1 functional impairment [1–3]. In 2007, Kahn emphasized the need to define and focus on PICS, and the Society of Critical Care Medical Society (SCCM) established the PICS Working Group in 2012 to define the syndrome and raise awareness of its impact on patients and their families [4]. PICS is characterized by a set of new or increased cognitive, mental, and physical dysfunctions that occur after a survivor is transferred from the ICU, collectively referred to as “PICS”. Physiological dysfunction is characterized by ICU-acquired weakness, disuse atrophy, and impaired ability to perform activities of daily living. Cognitive dysfunction is characterized by impaired memory and attention, decreased executive ability, reduced speed of thought processing, and impaired visuospatial ability. Psychiatric dysfunction is characterized by anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [4]. Mental health impairment in the patient’s family, identified as PICS-F, includes the occurrence of adverse psychological outcomes such as anxiety, acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and complex grief, which can persist for up to 4 years after ICU discharge [5]. PICS-F is also included in PICS [6]. PICS is estimated to affect 50–70% of people who have been in an ICU [7].

Bibliometrics is a widely used method for examining scholarly publications, both qualitatively and quantitatively [8], and can be used to analyze publications by country, researcher, journals, authors, and keywords to establish the lineage of disciplinary development, analyze changes in hot spots, and reveal the direction of development frontiers [9]. It can provide new researchers with a macroscopic understanding of the discipline, as well as identify important researchers, journals, and publications for focused reading to quickly familiarize themselves with the basic situation of the discipline, understand the weaknesses of the discipline’s research, and provide ideas for future research.

Currently, the only bibliometric study available for PICS is a study that analyzed all publications on PICS from 2012 to 2020, including original research articles, reviews, editorial articles or letters, meeting abstracts, protocol papers, case reports, research letters, and book reviews. The analysis provided an overview of the macro-distribution of overall research on PICS and focused on the 100 highest citation count articles [10]. However, a comprehensive analysis of research trends and hotspots for PICS is currently lacking. Therefore, we conducted a bibliometric study based specifically on original research articles and reviews related to PICS, as these are considered to be more focused on current research. We analyzed the research hotspots and trends from the research field of the main researchers, journal and field distribution, the keyword Co-Occurrence Network, the keyword timeline view, and the keywords with the strongest citation bursts to further improve research on PICS-related hotspots and trends.

Material and Methods

DATA AND SEARCH STRATEGIES:

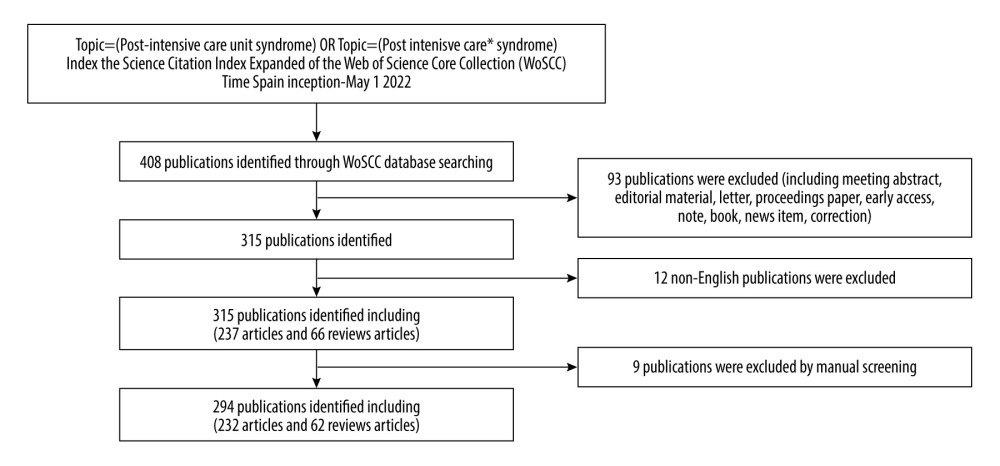

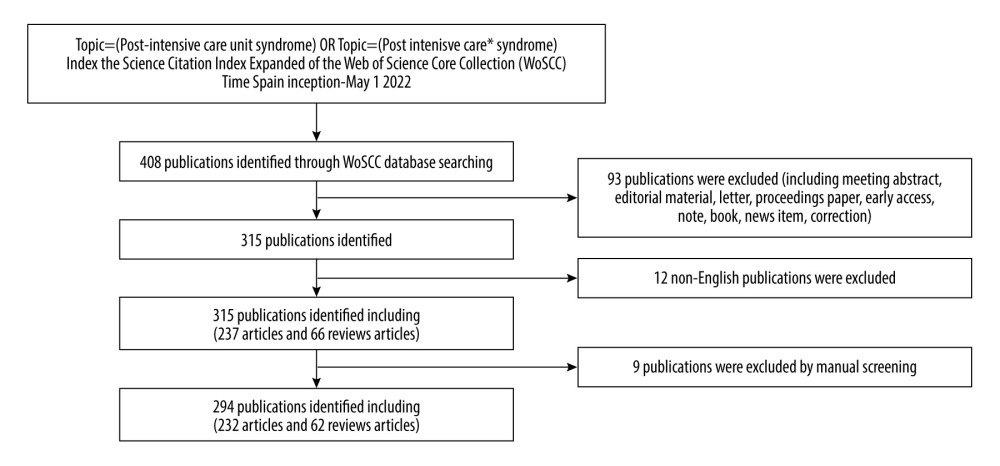

In this bibliometric analysis study, 2 reviewers (Xiayahu Li and Yaolin Li) independently examined all the publications, and the process for collecting publications is indicated in Figure 1. The study evaluated the global publication related to PICS from inception to May 1, 2022 by using the WoS Databases collection (Philadelphia, PA, USA). The keywords for the topic were “post-intensive care syndrome” and its derivatives, the language was English, and only original articles and reviews were included. Relevant publications were identified by scanning titles, abstracts, and keywords. The contents of the publications were then inspected individually. This analysis excluded publications that did not involve PICS or medicine. We recorded data on authors, countries, organizations, journals, impact factors (IFs), Web of Science (WoS) study categories, document types, paper publication time, and the most frequently used keywords, and all publications were exported to CSV and Excel files. The local Ethics Committee waived consent when consulted.

BIBLIOMETRIC ANALYSIS AND VISUALIZATION:

We downloaded the WoSCC records and converted them into plain text files for export, and then imported them into CiteSpace 5.8.3R for bibliometric and visual analysis. Then, we analyzed trends with CiteSpace in the number and growth of publications per year, explored collaborative networks among authors/institutions/countries, identified co-cited references, and captured keywords with strong citation bursts over time, culminating in the discovery of PICS research frontiers and emerging trends. Graphical mapping of keywords was performed using CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Scimago Graphica to assess the research priorities of the global medical community and changes in research directions. Varied knowledge graphs of CiteSpace visualization contain different nodes and links, and nodes with high centrality are generally characterized as hot spots or turning points in the field.

When evaluating clusters, the silhouette function is commonly used. If the silhouette value is larger than 0.7, the elements in the cluster have a high degree of homogeneity, indicating that the clustering results are significant, and if it is greater than 0.5, the clusters are usually deemed plausible.

Varied knowledge graphs of CiteSpace visualization contain different nodes and links, and nodes with high centrality are generally characterized as hot spots or turning points in the field.

Results

NUMBER OF PUBLICATIONS & INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION:

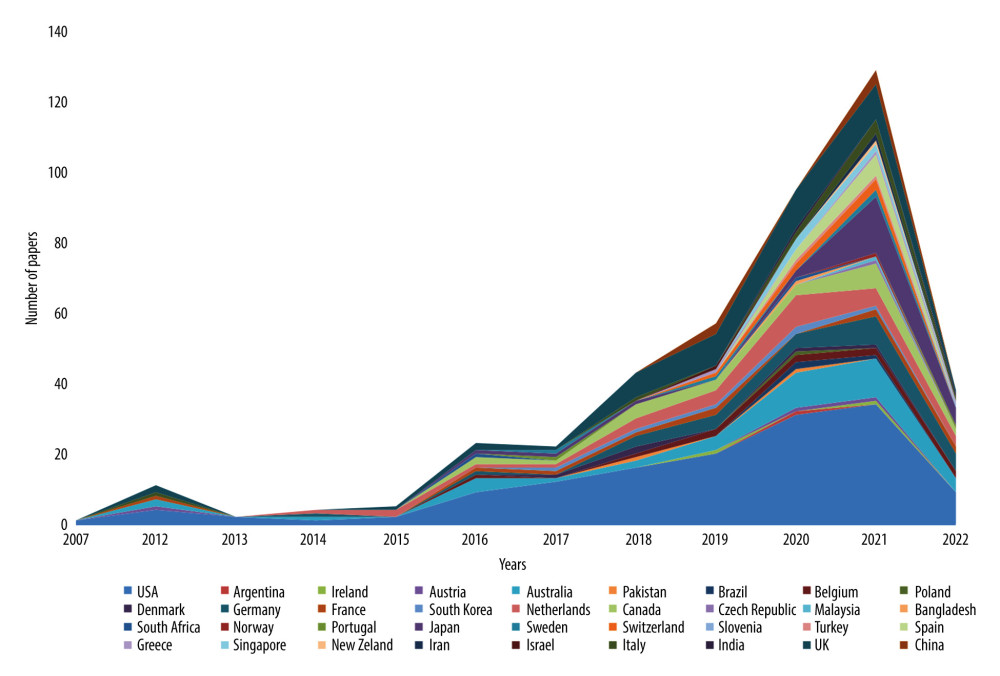

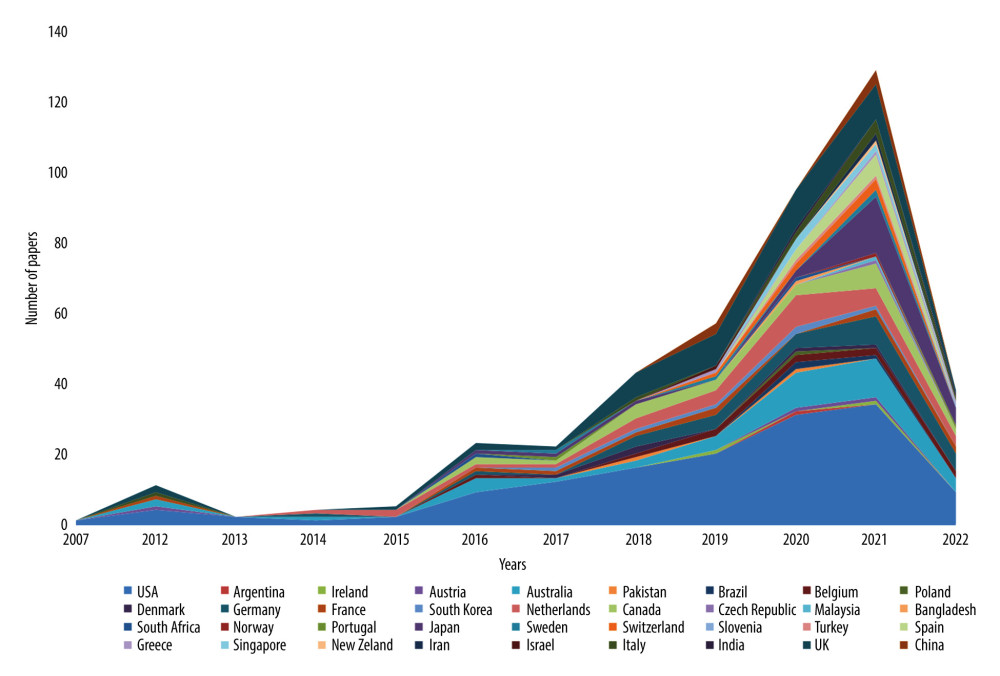

Since 2007, when PICS was initially presented in the documented literature, related studies began to appear formally in 2012 and have shown an increasing tendency year by year (Figure 2), but the number of papers is still relatively modest at this time.

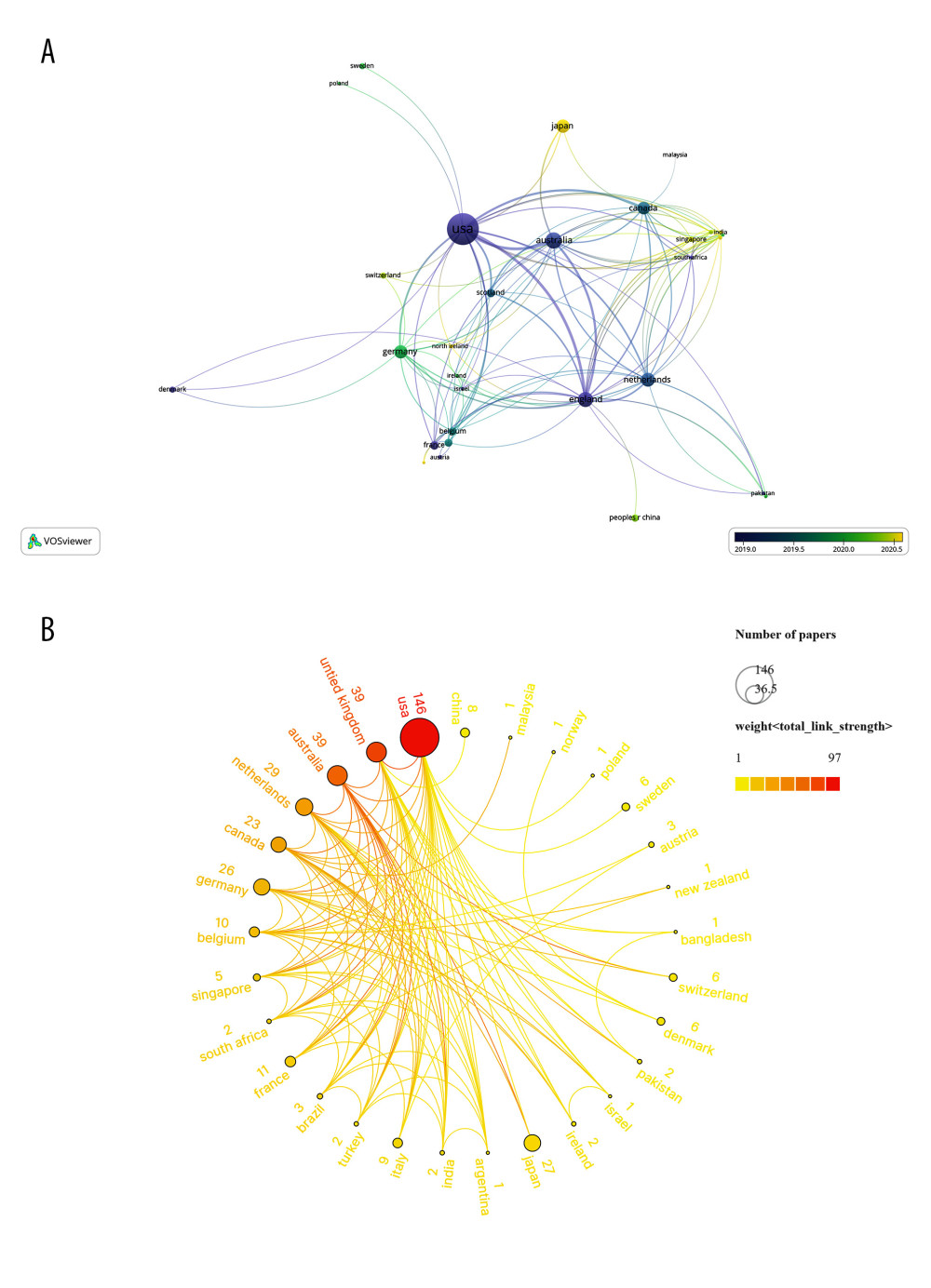

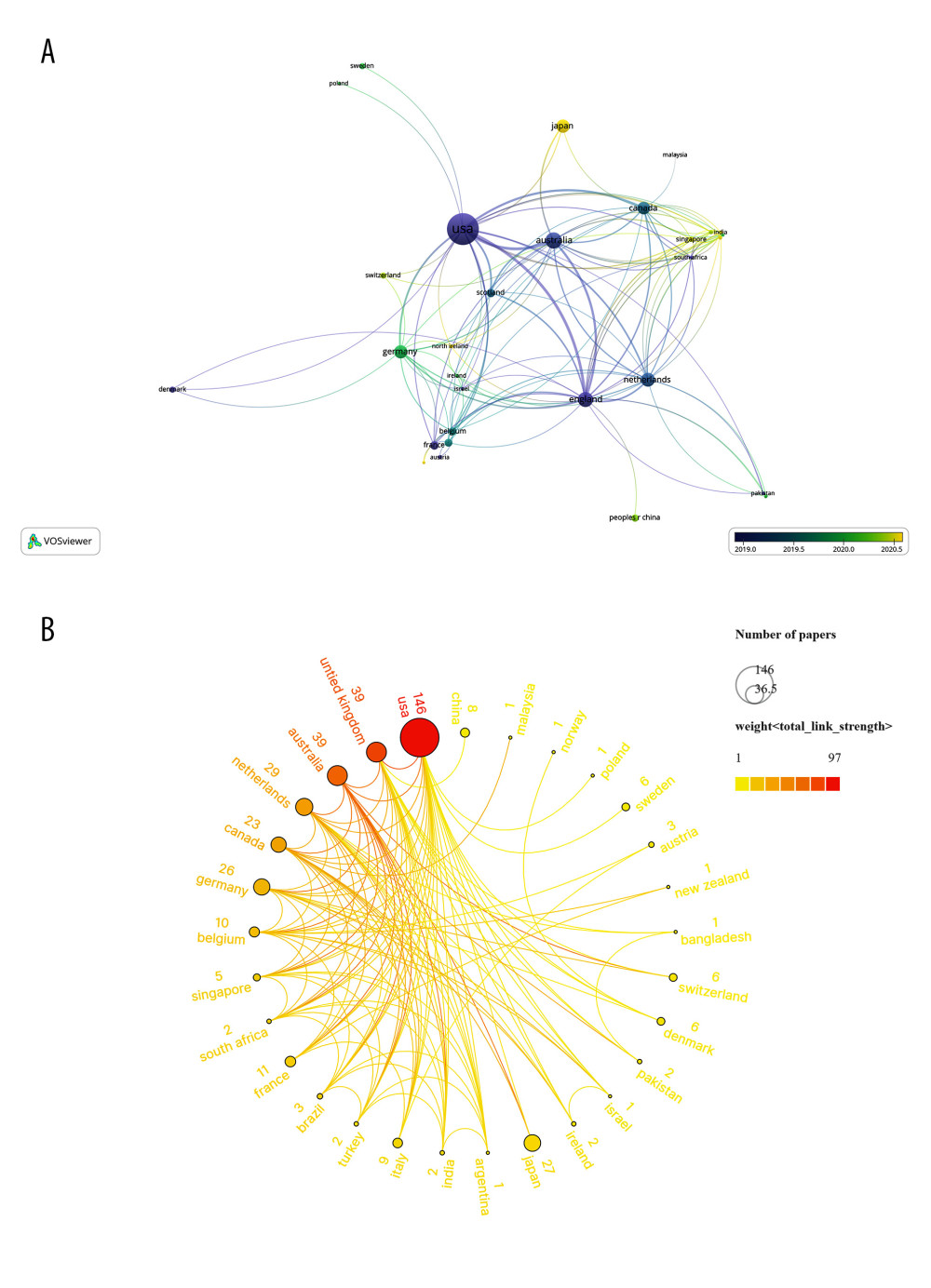

The USA dominated early studies and continued to lead the trend, but as time went on, more and more countries began to conduct PICS research. The USA was at the center of the international collaboration network (Figure 3) and had the strongest ties with other regions, with Europe and Australia as the main collaborators. China was an isolated country in the network; its research focused on its own country and had little cross-national collaboration.

AUTHORS AND AUTHOR CO-CITATION ANALYSIS:

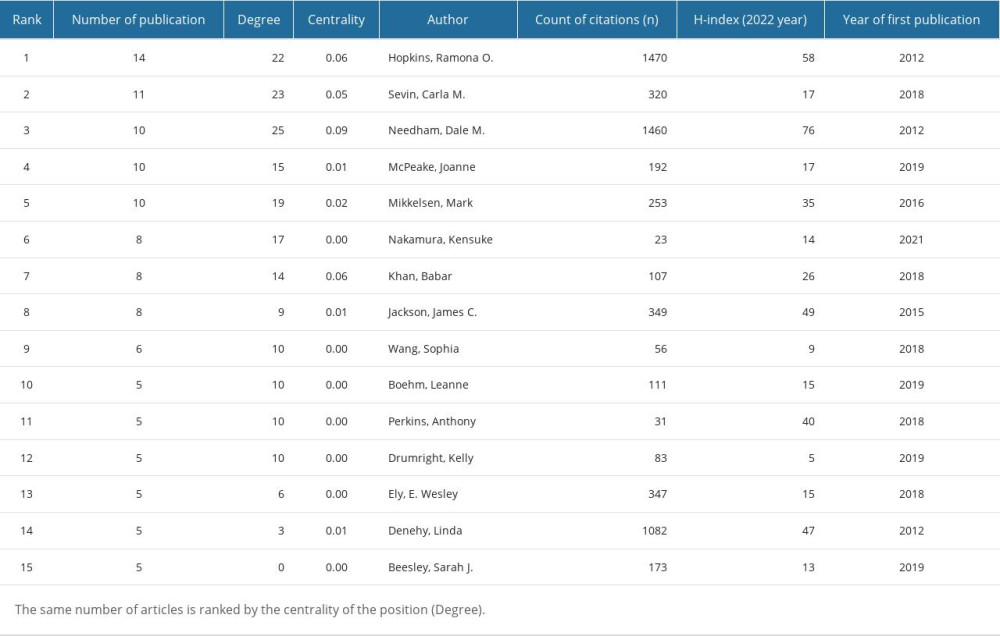

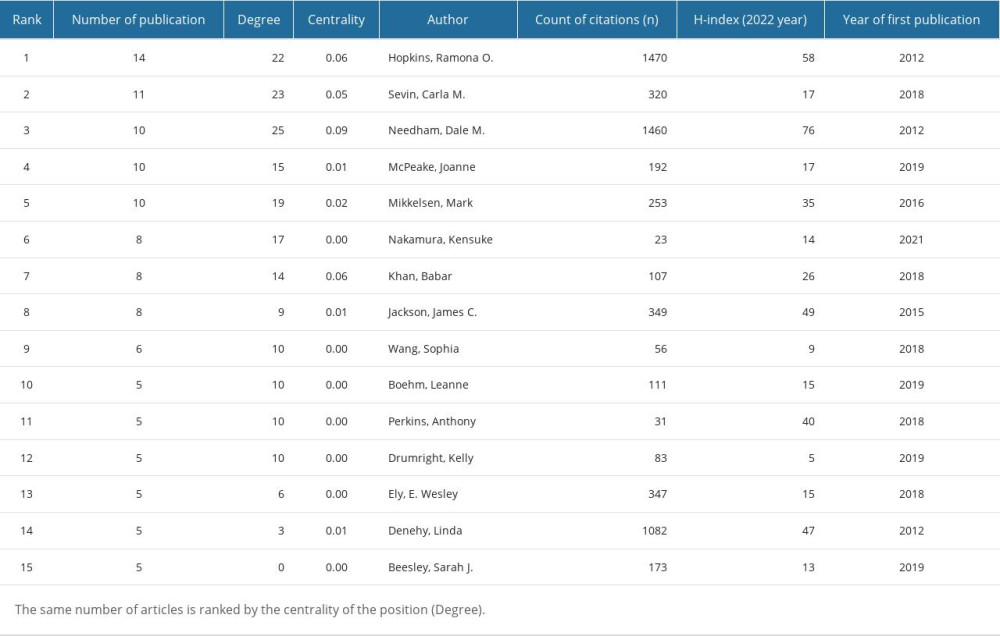

The authors who had published more than 5 articles are presented in Table 1, with Amona O Hopkins having the most articles (14). Furthermore, all authors with more than 1000 citations were members of the OACIS group that organized the Critical Care Conference and had 1052 citations of their research as of May 1, 2022 [4]. The centrality distribution of researchers, with the highest being Dale M Needham (0.09), and all less than 0.1, suggested that there is currently a temporary lack of researchers who can be considered critical nodes. According to the H-index distribution, researchers with a higher H-index focused on and studied PICS earlier.

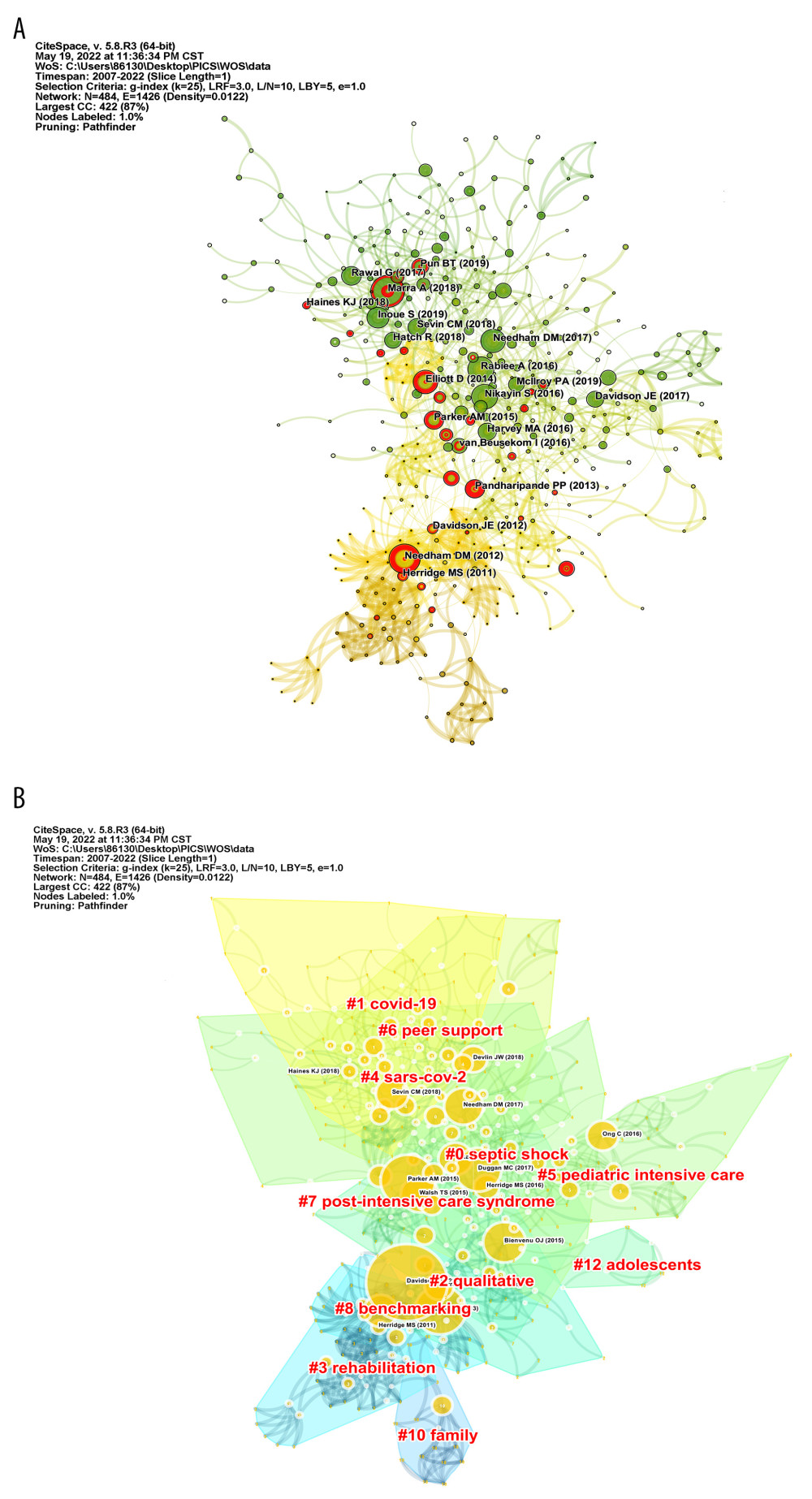

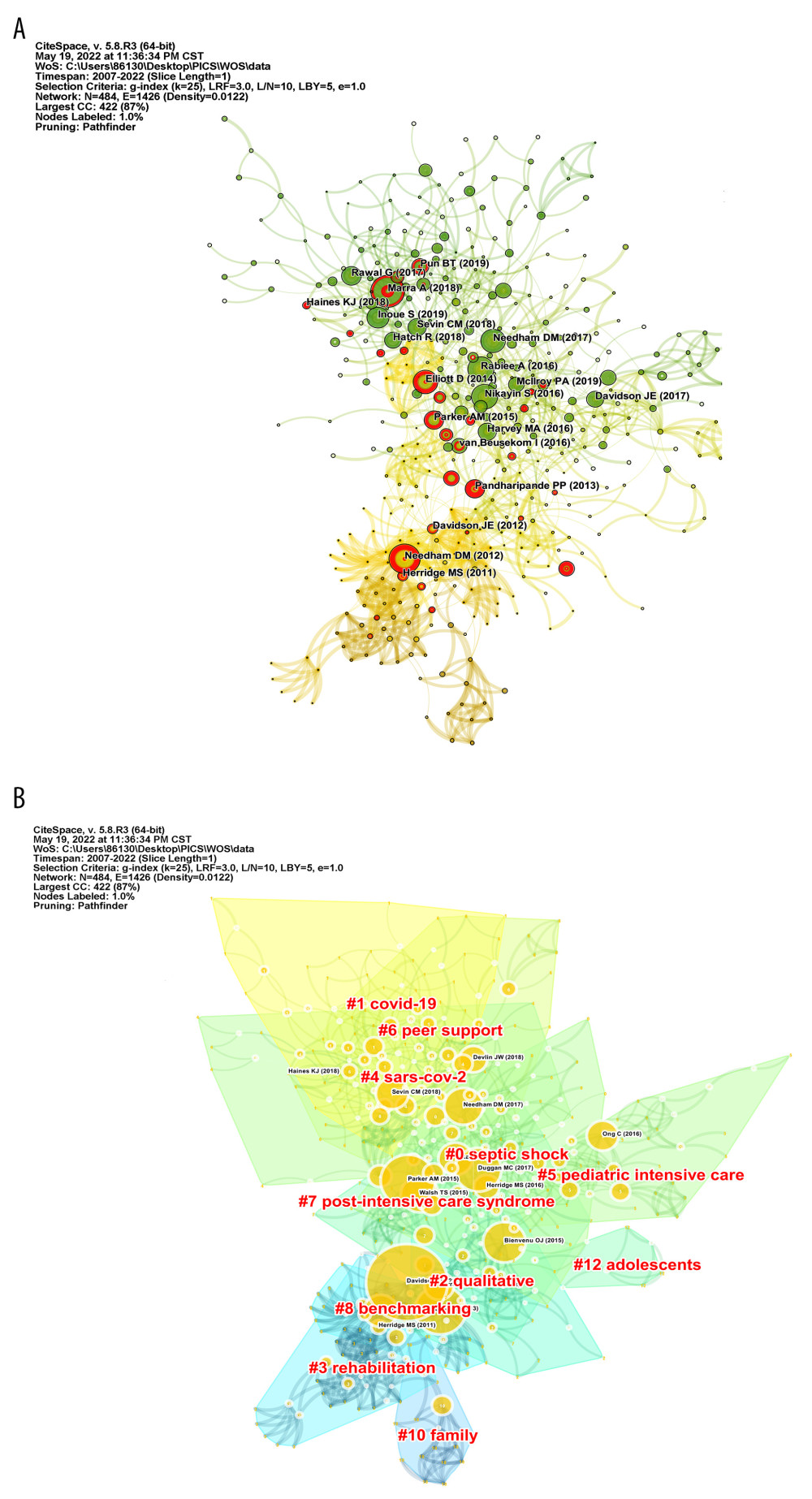

The author co-citation analysis graph was generated using CiteSpace (Figure 4) to depict authors of high-quality studies and their research areas. For instance, Dale Needham’s 2 papers published in 2012 and 2017 had high centeredness and belonged to the “rehabilitation, benchmarking, family” and “septic shock, peer support” clusters, respectively. Currently, the main research areas for the primary investigators included “SEPTIC SHOCK”, “COVID-19”, “QUALITATIVE”, “REHABILITATION”, “SARS-COV-2”, “PEDIATRIC INTENSIVE CARE”, “PEER SUPPORT”, “POST-INTENSIVE CARE SYNDROME”, “BENCHMARKING”, “FAMILY”, and “ADOLESCENTS:. The timeline indicated that the primary researchers focused on “FAMILY” and “REHABILITATION” in the early research stages. As time progressed, research shifted towards children and adolescents, as well as peer support. Furthermore, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, COVID-19 had also emerged as a research topic for the primary investigators in recent years.

JOURNAL AND FIELD DISTRIBUTION:

We selected a total of 16 journals that published more than 5 PICS-related studies and queried the 2021 Impact Factor presented in the figure (Supplementary Figure 1), The most published journal was CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE (29), Journal Citation Reports (JCR) were distributed in Q1 (4), Q2 (5), Q3 (5), and Q4 (2), respectively. The distribution of research areas included in the journals, as expected, was dominated by critical care medicine and nursing, indicating that researchers are mainly concentrated in these fields. The double map overlay of journals is presented in Supplementary Figure 2. The figure indicates that the main citing journals were from the fields of Medicine, Medical, and Clinical. On the other hand, the cited journals were mainly from 2 aspects: “Health, Nursing, Medicine” (z=5.36, f=2596) and “Psychology, Education, Social” (z=1.73, f=966).

KEYWORDS ANALYSIS:

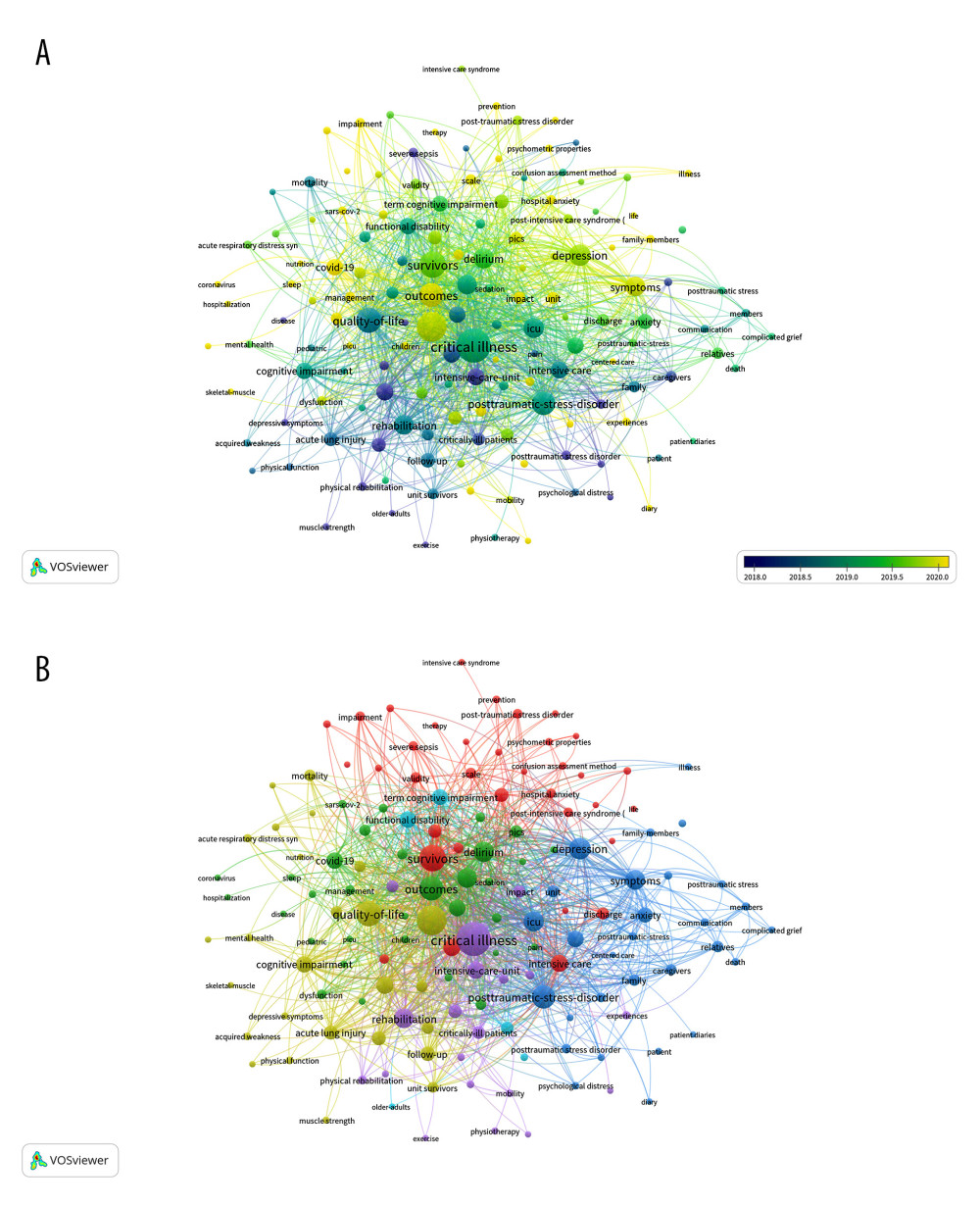

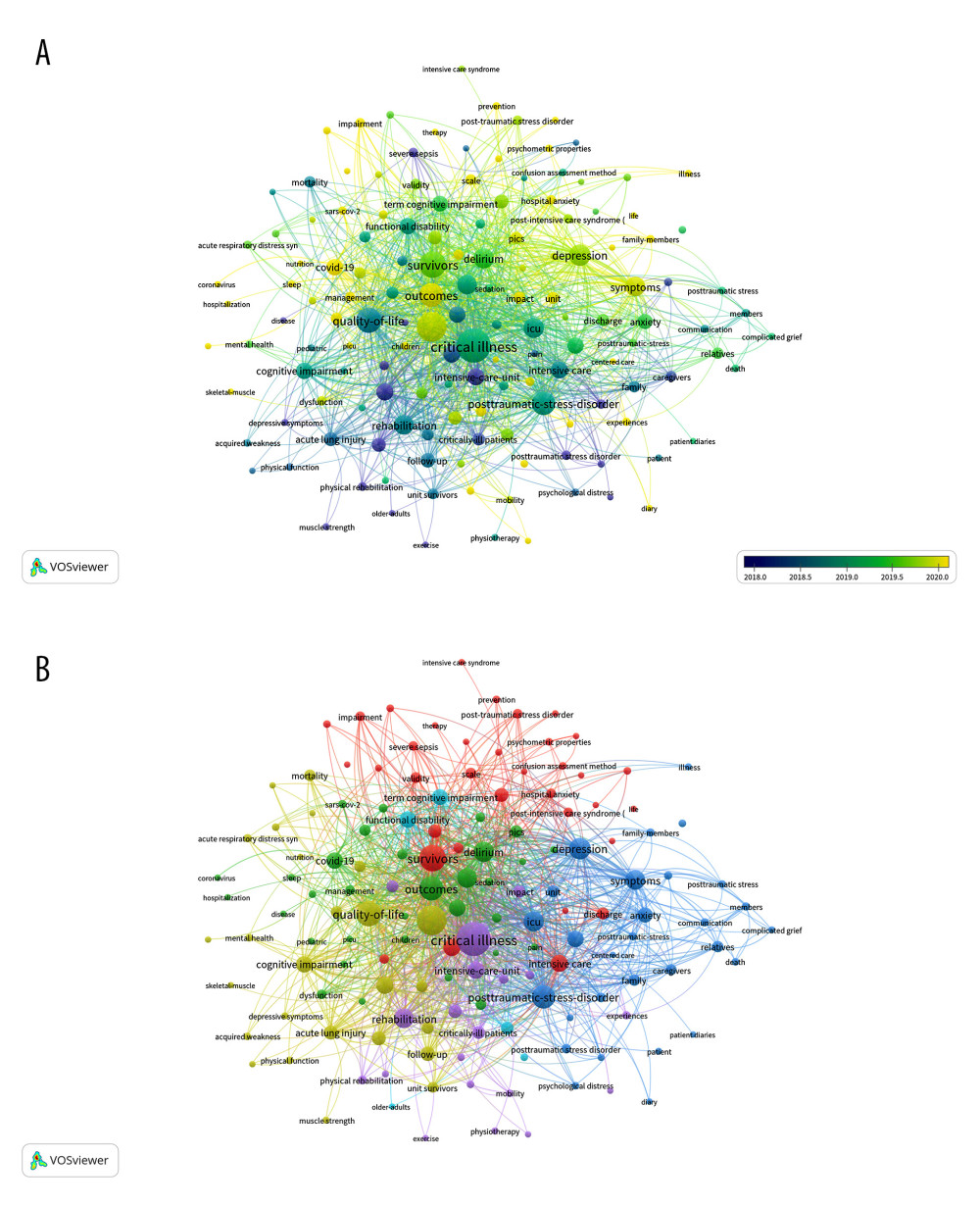

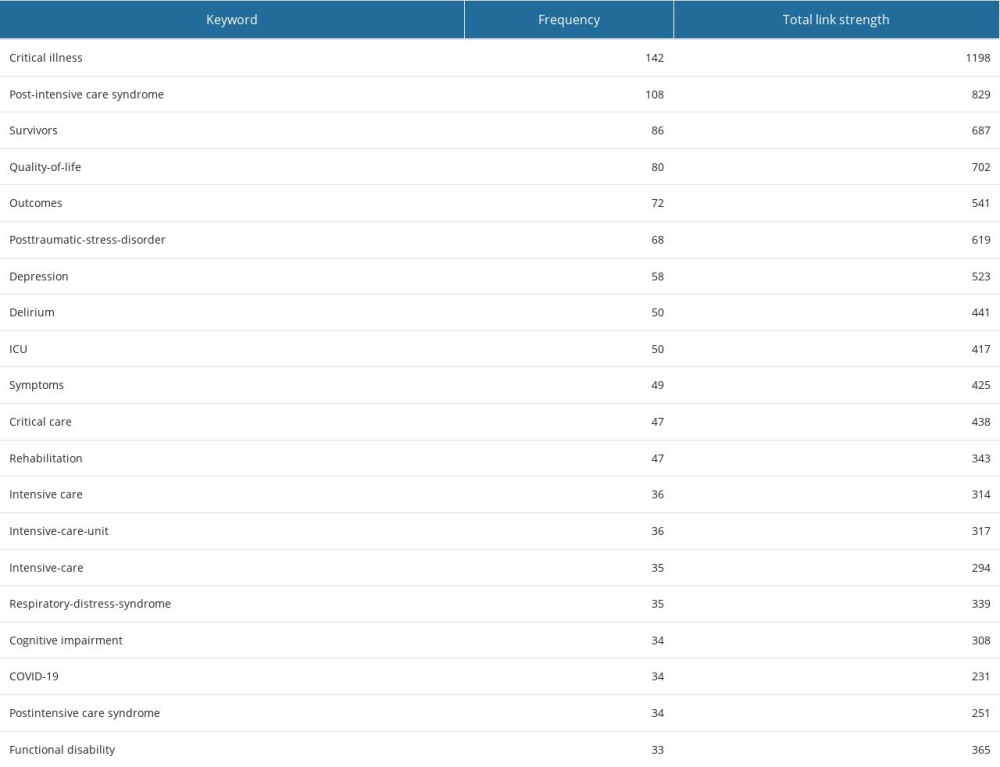

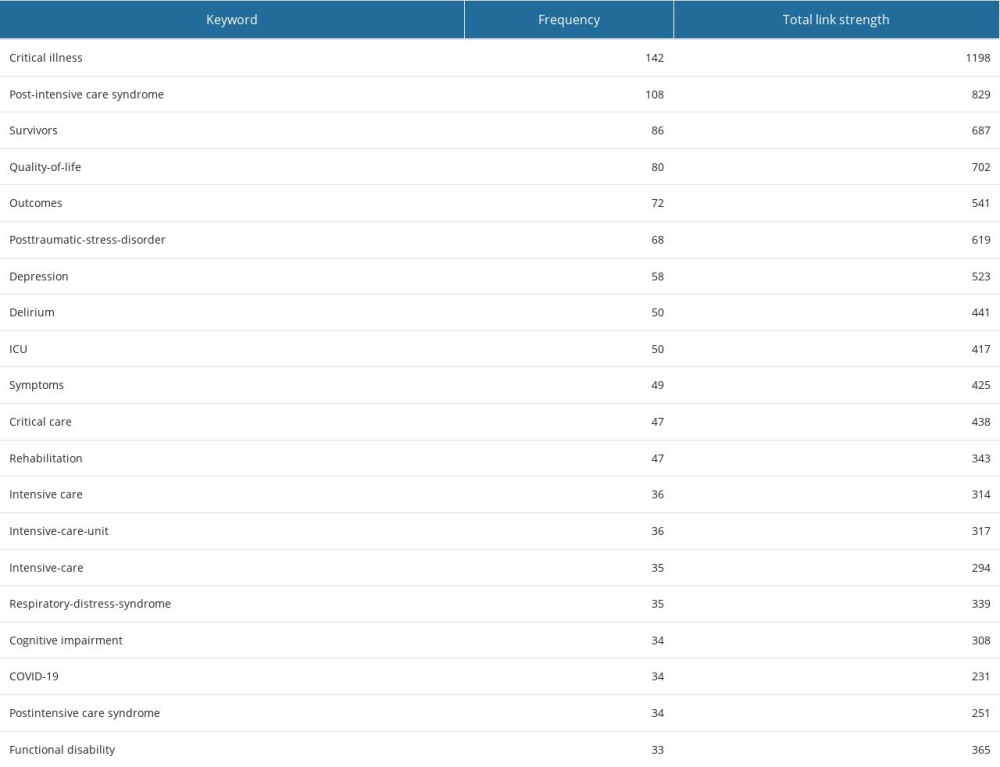

Keywords indicate the hot spots and trends in the research field according to the bibliometric theory. There were 1246 keywords Co-Occurrence analyzed by VOSviewer software, and a total of 146 keywords with a frequency of 5 occurrences or more were screened and analyzed (Figure 5). The 10 most frequent keywords and their link strength with other keywords are shown in Table 2. The keywords indicated that PICS-related studies were mainly clinical observations, and the most observational studies were about delirium and psychiatric impairments, fewer studies about physical impairments, and fewer studies about mechanisms and intervention modalities, and future studies need to focus on mechanisms and the direction of therapeutic interventions.

Using CiteSpace and the LLS algorithm to cluster keywords and generate a timeline view (Supplementary Figure 3), it can be observed that since the initial observation of PICS phenomena in 2007, research has primarily focused on describing quality of life. In 2012, the research center shifted to “Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome” and “Sepsis,” and in 2016, the research hotspots shifted again to “Cognitive Impairment” and “Postintensive Care Syndrome-Family.”

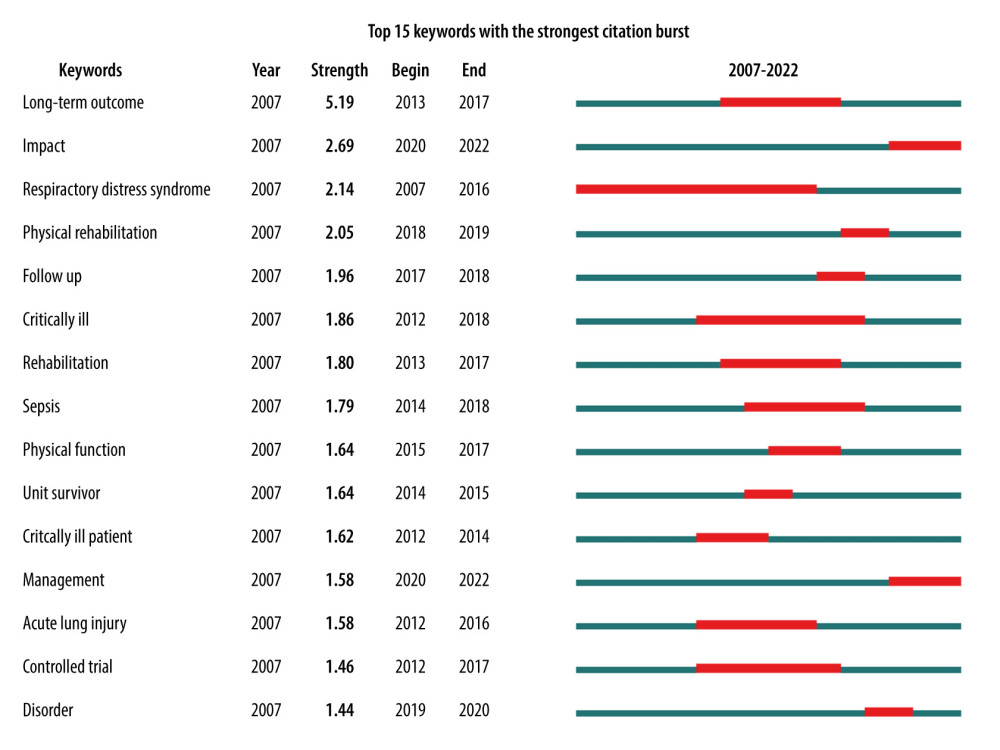

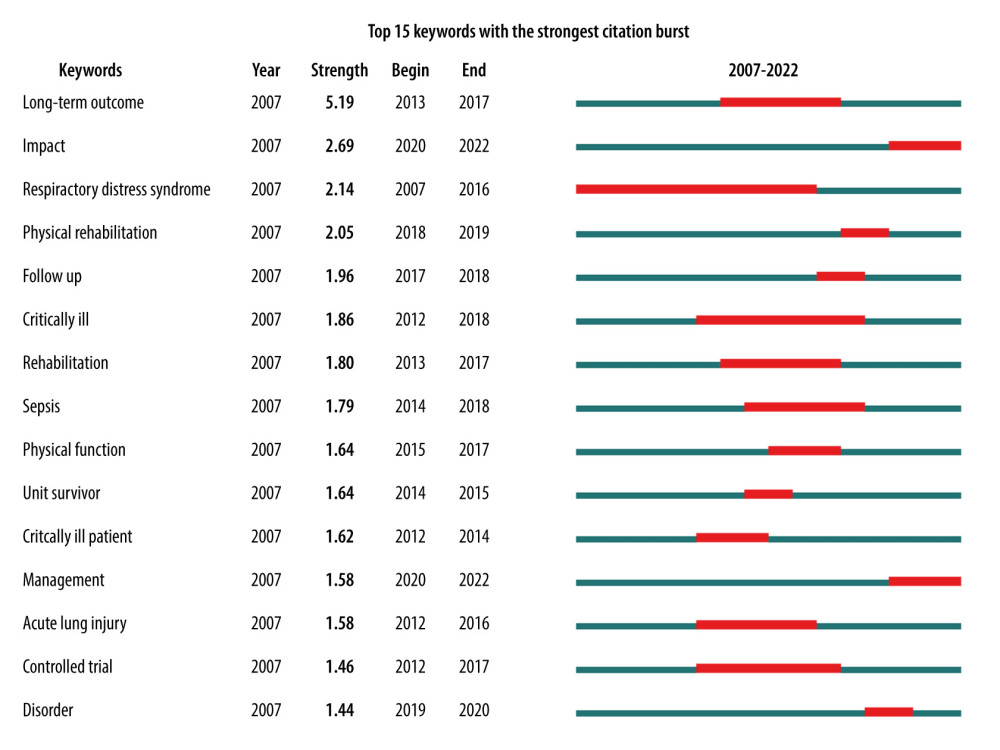

CiteSpace was used to detect citation burst keywords [11]. Figure 6 shows the top 15 keywords with the strongest citation burst from 2007 to 2022. The latest keywords were ‘long-term outcome‘, ’impact‘, ‘respiratory distress syndrome‘, ’physical rehabilitation‘, ‘follow-up’, ‘critical illness‘, ‘rehabilitation’, ‘sepsis’, ‘Physical function’, ‘unit survivor’, ‘critical ill patient’, ‘management’, ‘acute lung injury‘, ‘controlled trial’, and ‘disorder’. The keyword ‘long-term outcome’ that emerged in 2013 showed the strongest citation burst (5.19), marking the transition and intensity of hot spots.

Discussion

RESEARCH STATUS:

Based on bibliometric analysis, there was an observed increasing trend in PICS-related original research articles and reviews, particularly after 2017, which is consistent with previous studies [10]. The most productive countries were the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. While there was close cooperation between regions, it was primarily limited to the United States, Australia, and European countries. East Asia has a notable number of publications, but lacked cooperation, with only a few publications from Japan (27) and China (8).

The primary investigators of this study belong to the OACIS group and all of them are actively involved in research, with no clear leader identified. Although Dale Needham is considered the most important researcher, he cannot be labeled as a central researcher based on the analysis. Over time, the research focus of the primary investigators has shifted from general PICS topics such as clinical descriptions, risk factors, and treatment standards to specific populations, such as PICS in children and adolescents and the role of peer support. Additionally, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, PICS research related to COVID-19 has also become a part of the primary investigators’ research field.

After analyzing the included journals, it was found that the majority of PICS-related research is related to intensive care. Currently, the primary research fields are Medicine/Medical/Clinical based on the distribution of authors and publications, with most studies focusing on clinical aspects. Additionally, some studies have addressed PICS from the perspectives of Psychology, Education, and social sciences. However, other aspects, such as molecular biology and case physiology, have received relatively little attention.

PHYSICAL IMPAIRMENTS: Physical impairments in critically ill patients can manifest as critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP), critical illness myopathy (CIM), and critical illness polyneuromyopathy (CIPNM) [12]. These conditions lead to muscle loss, which can be caused by microvascular ischemia, catabolism, and disuse myasthenia. Microvascular injury can also cause neuroischemia, sodium channel dysfunction, and neuromitochondrial damage, which can result in critical illness-related neuropathy, myopathy, or both [13]. These conditions are associated with prolonged ICU stay, ventilator use, and increased in-hospital mortality [14]. Certain risk factors have been identified, including female gender, sepsis, catabolic state, multi-organ failure, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, long duration of mechanical ventilation, braking, hyperglycemia, glucocorticoid, and neuromuscular blocker use [13]. Currently, the risk factors for physical impairments are concentrated on cardiac arrest [15], respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19 [16–18], sepsis [19], and other related factors.

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENTS: Cognitive impairments can manifest in various areas, such as memory, executive function, language, attention, and visuospatial abilities. These impairments may be associated with a history of cognitive impairment, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, organ failure, hypotension, frequency, severity of delirium [20], and advanced age [21]. A low level of education and delayed mobilization are also risk factors for cognitive impairment after ICU. Women are more prone to cognitive impairment [22]. Additionally, the number of days of opioid use has been strongly associated with cognitive impairment [23].

MENTAL IMPAIRMENTS: Anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are common mental impairments experienced by patients after intensive care treatment [7]. The prevalence rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD are approximately 30%, 70%, and 10–50%, respectively [12,24], with depression being significantly correlated with patient mortality [25]. Patients’ psychological distress, such as anxiety and fear, are associated with physiological impairments such as severe sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure, trauma, hypoglycemia, and hypoxemia [3,26–28], as well as an uncomfortable environment [29] and altered sleep and circadian rhythms [30]. These factors are considered potential risk factors for the development of psychiatric impairments during intensive care treatment.

PICS-F: Witnessing critical illness can cause mental symptoms in family members or caregivers, such as depression and anxiety [31]. Depression, anxiety, and trauma-related mental impairments are the most common symptoms, with depression being the most prevalent, followed by anxiety [32]. The prevalence of mental symptoms is highest during ICU admission and hospitalization and decreases over time. For family members, the highest prevalence of depression is during ICU admission and hospitalization (70.3–90%), which decreases to 5–36% after 6 months [33–35]. The prevalence of anxiety during ICU hospitalization is 42–80% and decreases to 15–24% after discharge [35]. Contributing factors may include short ICU visiting hours, the cared-for person’s perception of imminent death, communication barriers with ICU doctors [36], and increased psychological stress [37].

PREVENTION OF PICS: Research on preventing and treating PICS has primarily focused on the hospitalization period. Various initiatives have been studied to address this issue, including early mobilization [38], individualized sedation tailored to patients’ needs [39,40], early psychological interventions [41], and the use of ICU diaries [42]. The treatment strategy has now shifted towards an integrated management approach, as indicated by the increased emphasis on the keyword ‘management’ from 2020 to 2022. The most extensively studied management approach is the bundle approach, which has evolved from the “ABCDE bundle” to the “ABCDEF bundle.” This approach includes assessment, management, and prevention of pain (A), spontaneous breathing and awakening tests (B), choice of analgesia and sedation (C), delirium assessment, prevention, and management (D), early action and exercise (E), and family engagement and empowerment (F) [40].

CURRENT STATUS OF PICS TREATMENT: Therapeutic studies on physical impairments have examined early activity [43], electrical stimulation [44], and glucose control [45]. However, there is a dearth of research on post-ICU rehabilitation. Recent studies on cognitive impairments have mainly been part of larger investigations, with delirium being the most common focus. However, these studies have been limited by short-term follow-up periods, with most lasting only 6 months. While some treatment options combining neuroesthetics and art have been proposed [46–48], research on the pharmaceutical and medical economics of cognitive impairment is lacking. Moreover, no studies have been carried out on the social or family burden of cognitive impairment, and the dominant approach to treatment involves in-hospital interventions based on risk factors.

Studies on mental impairments have suggested different treatment modalities, including biological, psychological, family, and socioeconomic support [49–51]. Our analysis of keywords and clustering shows that most associated words in the current study relate to disease names or specific manifestations of mental impairments, indicating a focus on risk factors for mental impairments and their related classifications and manifestations.

Our findings indicate that only a few studies have been conducted on PICS-F, with most focusing on the post-2020 period, and these studies have mainly been observational. Although some interventional studies on PICS-F exist, including psychological interventions facilitated by a Mobile Health App [52], ICU diary, a patient/family educational pamphlet [53], and a Virtual Reality protocol [54], they have been limited in scope, lacking social and economic impact studies, and are small in size. Moreover, PICS-F interventions lack uniqueness and innovation, with the reviewed studies primarily combining modern communication technology with less innovative medical interventions. Furthermore, no studies have specifically addressed the economic and social aspects of caregiving.

LIMITATIONS:

The small number of articles selected for our study correlates with the small number of PICS research papers, which makes it difficult to avoid bias. We only included articles in English, in the PICS field, and that were included in the WoS, and subsequent studies may expand the database search. As PICS is a broader concept, the limitation of the number of papers did not allow for narrower fields to be selected for detailed study, so selecting the whole of PICS as the object of study would not have made the study more specific.

Conclusions

This review presents a comprehensive summary and analysis of the development trends and hot spots in PICS research. The recent research in this field has primarily focused on clinical and nursing studies, with limited emphasis on pathogenesis. To determine the root cause of PICS occurrence, it is necessary to explore its molecular biology or genetic predispositions, which would provide better guidance for optimizing treatment protocols and developing drugs. Furthermore, the number of studies on this topic remains low, and international cooperation is limited to Europe, USA, and Australia. Therefore, it is imperative to accelerate research in related areas and to strengthen collaboration between countries to address this increasingly prevalent problem.

Figures

Figure 1. Flow chart of literature screening included in this study.

Figure 1. Flow chart of literature screening included in this study.  Figure 2. Annual trends in publications and the composition of the number of papers by country are plotted. The time span is from inception to May 1, 2022.

Figure 2. Annual trends in publications and the composition of the number of papers by country are plotted. The time span is from inception to May 1, 2022.  Figure 3. The network of countries. Figure A shows international cooperation in recent years, the time from before to now with the color blue to yellow over. Figure B shows the network of cooperation between countries, the connecting line indicates the international cooperation between different countries and regions in research, the size of the circle indicates the size of the number of articles issued, and the color of the circle indicates that the more the red color indicates that the cooperation links about more.

Figure 3. The network of countries. Figure A shows international cooperation in recent years, the time from before to now with the color blue to yellow over. Figure B shows the network of cooperation between countries, the connecting line indicates the international cooperation between different countries and regions in research, the size of the circle indicates the size of the number of articles issued, and the color of the circle indicates that the more the red color indicates that the cooperation links about more.  Figure 4. Author Co-citation Network. Figure A represents different researchers, with nodes representing them. The larger the node, the more frequently it is cited. The thickness and color of the inner circles of the nodes indicate the frequency of citations in different time periods. The lines between nodes represent the co-citation relationship, and their thickness indicates the strength of the co-citation. The color of the lines corresponds to the time of the first co-citation of the node, with the color changing from cool blue to warm red indicating the change of time from early to recent. Figure B, clustering analysis results are shown based on the LLS clustering method. Different color blocks represent different clusters. The position of the color blocks of the authors represented by different nodes indicates the corresponding research fields, with the color changing from cool blue to warm red indicating the change of time from early to recent.

Figure 4. Author Co-citation Network. Figure A represents different researchers, with nodes representing them. The larger the node, the more frequently it is cited. The thickness and color of the inner circles of the nodes indicate the frequency of citations in different time periods. The lines between nodes represent the co-citation relationship, and their thickness indicates the strength of the co-citation. The color of the lines corresponds to the time of the first co-citation of the node, with the color changing from cool blue to warm red indicating the change of time from early to recent. Figure B, clustering analysis results are shown based on the LLS clustering method. Different color blocks represent different clusters. The position of the color blocks of the authors represented by different nodes indicates the corresponding research fields, with the color changing from cool blue to warm red indicating the change of time from early to recent.  Figure 5. Keyword co-occurrence analysis mapping. Figure A is analyzed by the time relationship, the closer the yellow indicates the closer the time is from now. Figure B is analyzed by keyword clustering, and the same color is expressed as the same cluster keywords, indicating the distribution of keywords between different fields and the correlation of keywords in different fields.

Figure 5. Keyword co-occurrence analysis mapping. Figure A is analyzed by the time relationship, the closer the yellow indicates the closer the time is from now. Figure B is analyzed by keyword clustering, and the same color is expressed as the same cluster keywords, indicating the distribution of keywords between different fields and the correlation of keywords in different fields.  Figure 6. Top 15 keywords with strongest citation bursts. The keywords with the strongest citation bursts for publications on PICS research between 2007–2022. The red bars represent frequently cited keywords.

Figure 6. Top 15 keywords with strongest citation bursts. The keywords with the strongest citation bursts for publications on PICS research between 2007–2022. The red bars represent frequently cited keywords. References

1. Kosinski S, Mohammad RA, Pitcher M, What is post-intensive care syndrome (PICS)?: Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2020; 201(8); P15-P16

2. Elliott D, Davidson JE, Harvey MA, Exploring the scope of post-intensive care syndrome therapy and care: Engagement of non-critical care providers and survivors in a second stakeholders meeting: Crit Care Med, 2014; 42(12); 2518-26

3. Dowdy DW, Dinglas V, Mendez-Tellez PA, Intensive care unit hypoglycemia predicts depression during early recovery from acute lung injury: Crit Care Med, 2008; 36(10); 2726-33

4. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference: Crit Care Med, 2012; 40(2); 502-9

5. Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ, Family response to critical illness: Postintensive care syndrome-family: Crit Care Med, 2012; 40(2); 618-24

6. Harvey MA, Davidson JE, Postintensive care syndrome: Right care, right now…and later: Crit Care Med, 2016; 44(2); 381-85

7. Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM, Long-term complications of critical care: Crit Care Med, 2011; 39(2); 371-79

8. , Gauthier É: Bibliometric analysis of scientific and technological research: Science & Technology Redesign Project Statistics, 2002 88F0006X1998008

9. Hao T, Chen X, Li G, Yan J, A bibliometric analysis of text mining in medical research: Soft Computing, 2018; 22(23); 7875-92

10. Paul N, Albrecht V, Denke C, A decade of post-intensive care syndrome: A bibliometric network analysis: Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 2022; 58(2); 170

11. Chen C, CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature: J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol, 2006; 57(3); 359-77

12. Inoue S, Hatakeyama J, Kondo Y, Post-intensive care syndrome: Its pathophysiology, prevention, and future directions: Acute Med Surg, 2019; 6(3); 233-46

13. Kress JP, Hall JB, ICU-acquired weakness and recovery from critical illness: N Engl J Med, 2014; 370(17); 1626-35

14. Dinglas VD, Aronson Friedman L, Colantuoni E, Muscle weakness and 5-year survival in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors: Crit Care Med, 2017; 45(3); 446-53

15. Lilja G, Follow-up of cardiac arrest survivors: why, how, and when? A Practical Approach: Semin Neurol, 2017; 37(1); 88-93

16. Mayer KP, Sturgill JL, Kalema AG, Recovery from COVID-19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome: The potential role of an intensive care unit recovery clinic: A case report: J Med Case Rep, 2020; 14(1); 161

17. Lutchmansingh DD, Knauert MP, Antin-Ozerkis DE, A clinic blueprint for post-coronavirus disease 2019 RECOVERY: Learning from the past, looking to the future: Chest, 2021; 159(3); 949-58

18. Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: A cross-sectional evaluation: J Med Virol, 2021; 93(2); 1013-22

19. Fujinami Y, Inoue S, Ono Y, Sepsis induces physical and mental impairments in a mouse model of post-intensive care syndrome: Journal of clinical medicine, 2021; 10(8); 1593

20. Wade DM, Howell DC, Weinman JA, Investigating risk factors for psychological morbidity three months after intensive care: A prospective cohort study: Crit Care, 2012; 16(5); R192

21. Yao L, Li Y, Yin R, Incidence and influencing factors of post-intensive care cognitive impairment: Intensive Crit Care Nurs, 2021; 67; 103106

22. Habib S, Khan A, Afridi MI, Frequency and predictors of cognitive decline in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: J Coll Physicians Surg Pak, 2014; 24(8); 543-48

23. Fernández-Gonzalo S, Navarra-Ventura G, Bacardit N, Cognitive phenotypes 1 month after ICU discharge in mechanically ventilated patients: A prospective observational cohort study: Crit Care, 2020; 24(1); 618

24. Canavera KE, Elliott DA, Mental health care during and after the ICU: A call to action: Chest, 2020; 158(5); 1835-36

25. Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, Anxiety, Depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after critical illness: A UK-wide prospective cohort study: Crit Care, 2018; 22(1); 310

26. Davydow DS, Desai SV, Needham DM, Bienvenu OJ, Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review: Psychosom Med, 2008; 70(4); 512-19

27. Jackson JC, Obremskey W, Bauer R, Long-term cognitive, emotional, and functional outcomes in trauma intensive care unit survivors without intracranial hemorrhage: J Trauma, 2007; 62(1); 80-88

28. Davydow DS, Hough CL, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, Symptoms of depression in survivors of severe sepsis: A prospective cohort study of older Americans: Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2013; 21(9); 887-97

29. Smith S, Rahman OStatPearls: Post Intensive Care Syndrome, 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing. Copyright© 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC

30. Pisani MA, Friese RS, Gehlbach BK, Sleep in the intensive care unit: Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2015; 191(7); 731-38

31. Davidson JE, Harvey MA, Patient and family post-intensive care syndrome: AACN Adv Crit Care, 2016; 27(2); 184-86

32. Serrano P, Kheir YNP, Wang S, Aging and postintensive care syndrome-family: A critical need for geriatric psychiatry: Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2019; 27(4); 446-54

33. Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL, Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the Intensive Care Unit: J Gen Intern Med, 2008; 23(11); 1871-76

34. Onrust M, Lansink-Hartgring AO, van der Meulen I, Coping strategies, anxiety and depressive symptoms in family members of patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A prospective cohort study: Heart Lung, 2022; 52; 146-51

35. van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: A literature review: Crit Care, 2016; 20; 16

36. Burchardi H, Let’s open the door!: Intensive Care Med, 2002; 28(10); 1371-72

37. Harris BR, Beesley SJ, Hopkins RO, Heart rate variability and subsequent psychological distress among family members of intensive care unit patients: J Int Med Res, 2021; 49(11); 3000605211057829

38. Connolly B, O’Neill B, Salisbury L, Blackwood B, Physical rehabilitation interventions for adult patients during critical illness: An overview of systematic reviews: Thorax, 2016; 71(10); 881-90

39. Vincent JL, Shehabi Y, Walsh TS, Comfort and patient-centred care without excessive sedation: The eCASH concept: Intensive Care Med, 2016; 42(6); 962-71

40. Ely EW, The ABCDEF bundle: Science and philosophy of How ICU liberation serves patients and families: Crit Care Med, 2017; 45(2); 321-30

41. Peris A, Bonizzoli M, Iozzelli D, Early intra-intensive care unit psychological intervention promotes recovery from post traumatic stress disorders, anxiety and depression symptoms in critically ill patients: Crit Care, 2011; 15(1); R41

42. Ednell AK, Siljegren S, Engström Å, The ICU patient diary – a nursing intervention that is complicated in its simplicity: A qualitative study: Intensive Crit Care Nurs, 2017; 40; 70-76

43. Fuke R, Hifumi T, Kondo Y, Early rehabilitation to prevent postintensive care syndrome in patients with critical illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis: BMJ Open, 2018; 8(5); e019998

44. Routsi C, Gerovasili V, Vasileiadis I, Electrical muscle stimulation prevents critical illness polyneuromyopathy: A randomized parallel intervention trial: Crit Care, 2010; 14(2); R74

45. Hermans G, De Jonghe B, Bruyninckx F, Van den Berghe G, Interventions for preventing critical illness polyneuropathy and critical illness myopathy: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014; 2014(1); CD006832

46. Pearce MT, Zaidel DW, Vartanian O, Neuroaesthetics: The cognitive neuroscience of aesthetic experience: Perspect Psychol Sci, 2016; 11(2); 265-79

47. Cinzia DD, Vittorio G, Neuroaesthetics: A review: Curr Opin Neurobiol, 2009; 19(6); 682-87

48. Gallo LMH, Giampietro V, Zunszain PA, Tan KS, COVID-19 and mental health: Could visual art exposure help?: Front Psychol, 2021; 12; 650314

49. Smith JM, Lee AC, Zeleznik H, Home and community-based physical therapist management of adults with post-intensive care syndrome: Physical Therapy, 2020; 100(7); 1062-73

50. Fernandes A, Jaeger MS, Chudow M, Post-intensive care syndrome: A review of preventive strategies and follow-up care: Am J Health System Pharm, 2019; 76(2); 119-22

51. Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R, Post-intensive care syndrome: An overview: J Transl Int Med, 2017; 5(2); 90-92

52. Petrinec A, Wilk C, Hughes JW, Delivering cognitive behavioral therapy for post-intensive care syndrome-family via a mobile health app: Am J Crit Care, 2021; 30(6); 451-58

53. Locke M, Eccleston S, Ryan CN, Developing a diary program to minimize patient and family post-intensive care syndrome: AACN Adv Crit Care, 2016; 27(2); 212-20

54. Vlake JH, van Bommel J, Wils EJ, Virtual reality for relatives of ICU patients to improve psychological sequelae: study protocol for a multicentre, randomised controlled trial: BMJ Open, 2021; 11(9); e049704

Figures

Figure 1. Flow chart of literature screening included in this study.

Figure 1. Flow chart of literature screening included in this study. Figure 2. Annual trends in publications and the composition of the number of papers by country are plotted. The time span is from inception to May 1, 2022.

Figure 2. Annual trends in publications and the composition of the number of papers by country are plotted. The time span is from inception to May 1, 2022. Figure 3. The network of countries. Figure A shows international cooperation in recent years, the time from before to now with the color blue to yellow over. Figure B shows the network of cooperation between countries, the connecting line indicates the international cooperation between different countries and regions in research, the size of the circle indicates the size of the number of articles issued, and the color of the circle indicates that the more the red color indicates that the cooperation links about more.

Figure 3. The network of countries. Figure A shows international cooperation in recent years, the time from before to now with the color blue to yellow over. Figure B shows the network of cooperation between countries, the connecting line indicates the international cooperation between different countries and regions in research, the size of the circle indicates the size of the number of articles issued, and the color of the circle indicates that the more the red color indicates that the cooperation links about more. Figure 4. Author Co-citation Network. Figure A represents different researchers, with nodes representing them. The larger the node, the more frequently it is cited. The thickness and color of the inner circles of the nodes indicate the frequency of citations in different time periods. The lines between nodes represent the co-citation relationship, and their thickness indicates the strength of the co-citation. The color of the lines corresponds to the time of the first co-citation of the node, with the color changing from cool blue to warm red indicating the change of time from early to recent. Figure B, clustering analysis results are shown based on the LLS clustering method. Different color blocks represent different clusters. The position of the color blocks of the authors represented by different nodes indicates the corresponding research fields, with the color changing from cool blue to warm red indicating the change of time from early to recent.

Figure 4. Author Co-citation Network. Figure A represents different researchers, with nodes representing them. The larger the node, the more frequently it is cited. The thickness and color of the inner circles of the nodes indicate the frequency of citations in different time periods. The lines between nodes represent the co-citation relationship, and their thickness indicates the strength of the co-citation. The color of the lines corresponds to the time of the first co-citation of the node, with the color changing from cool blue to warm red indicating the change of time from early to recent. Figure B, clustering analysis results are shown based on the LLS clustering method. Different color blocks represent different clusters. The position of the color blocks of the authors represented by different nodes indicates the corresponding research fields, with the color changing from cool blue to warm red indicating the change of time from early to recent. Figure 5. Keyword co-occurrence analysis mapping. Figure A is analyzed by the time relationship, the closer the yellow indicates the closer the time is from now. Figure B is analyzed by keyword clustering, and the same color is expressed as the same cluster keywords, indicating the distribution of keywords between different fields and the correlation of keywords in different fields.

Figure 5. Keyword co-occurrence analysis mapping. Figure A is analyzed by the time relationship, the closer the yellow indicates the closer the time is from now. Figure B is analyzed by keyword clustering, and the same color is expressed as the same cluster keywords, indicating the distribution of keywords between different fields and the correlation of keywords in different fields. Figure 6. Top 15 keywords with strongest citation bursts. The keywords with the strongest citation bursts for publications on PICS research between 2007–2022. The red bars represent frequently cited keywords.

Figure 6. Top 15 keywords with strongest citation bursts. The keywords with the strongest citation bursts for publications on PICS research between 2007–2022. The red bars represent frequently cited keywords. Tables

Table 1. The 15 authors with more than 5 articles are ranked by the number of publication published.

Table 1. The 15 authors with more than 5 articles are ranked by the number of publication published. Table2. The top 20 keywords and their strength of association with other keywords.

Table2. The top 20 keywords and their strength of association with other keywords. Table 1. The 15 authors with more than 5 articles are ranked by the number of publication published.

Table 1. The 15 authors with more than 5 articles are ranked by the number of publication published. Table2. The top 20 keywords and their strength of association with other keywords.

Table2. The top 20 keywords and their strength of association with other keywords. In Press

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparing Neuromuscular Blockade Measurement Between Upper Arm (TOF Cuff®) and Eyelid (TOF Scan®) Using Miv...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943630

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952