28 September 2023: Clinical Research

Superiority of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Over Nasogastric Feeding for Stroke-Induced Severe Dysphagia: A Comparative Study

Zhong Chang Yang1ABCG, Zhang Zu Yong2AG*, Li Hua3DEF, Wu Chun Li1CEFDOI: 10.12659/MSM.940613

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940613

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Patients with dysphagia due to stroke may require enteral feeding using either a nasogastric (NG) feeding tube or a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. This study aimed to compare outcomes from NG tube and PEG tube feeding in 40 patients with severe dysphagia due to stroke.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: We enrolled 40 patients admitted to the hospital from April 2019 to December 2022 due to severe stroke dysphagia, who were divided into the gastrostomy group (20 patients) and the nasogastric feeding group (20 patients) in accordance with the random number table method. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy was performed in both groups and we assessed differences in swallowing function, nutritional recovery, safety, and hope levels.

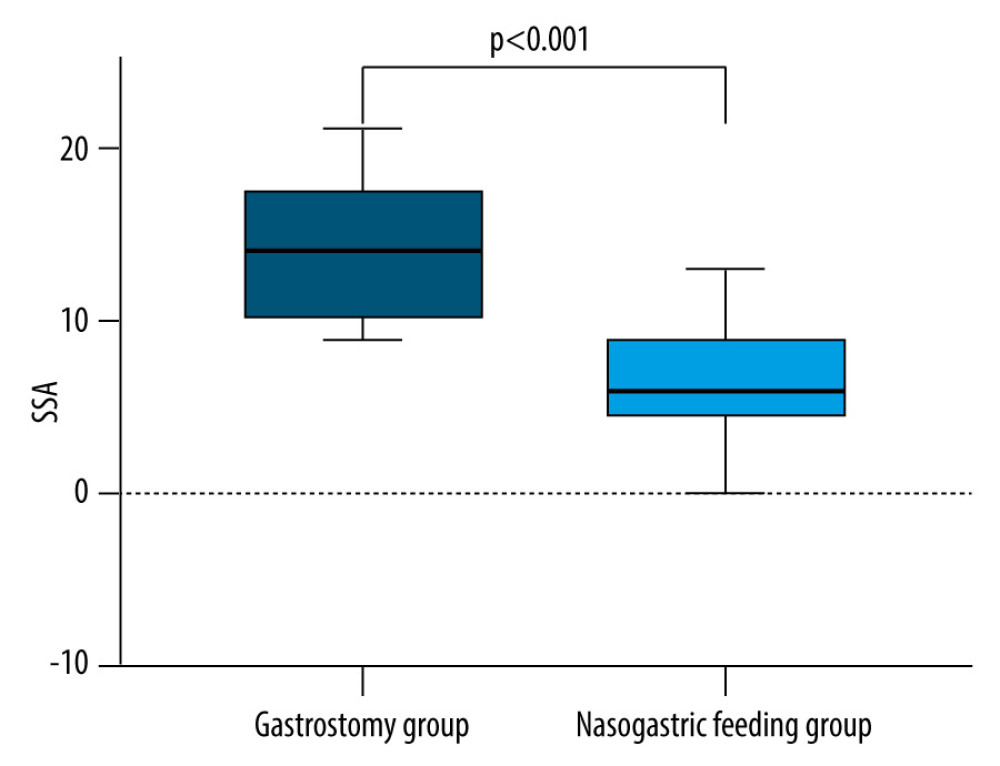

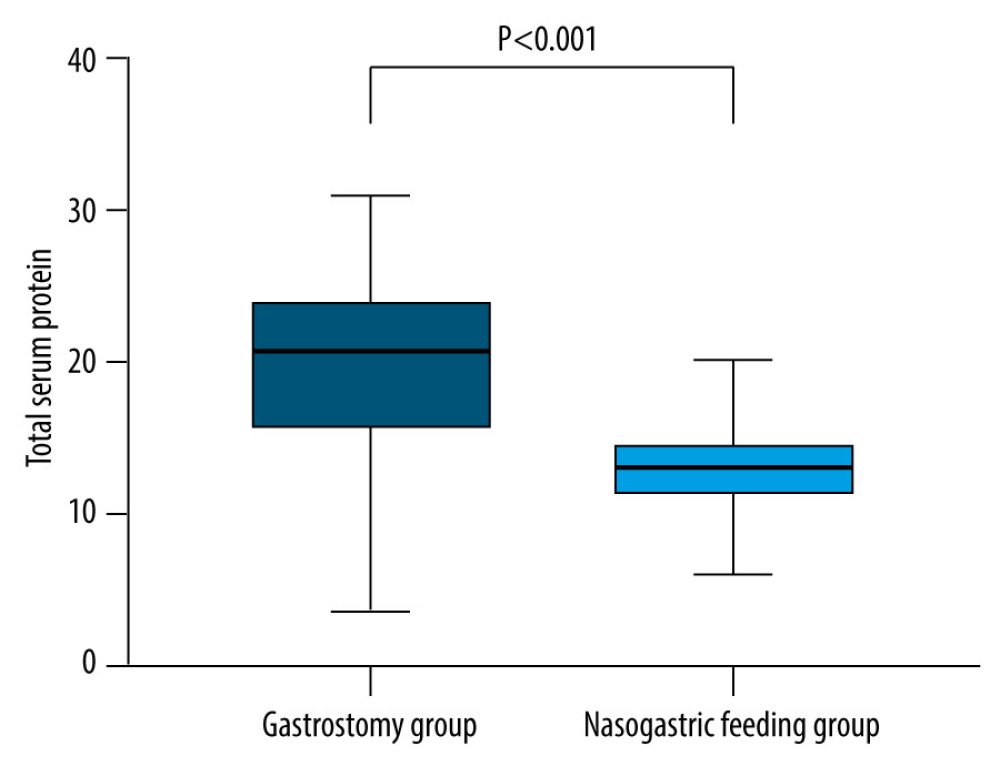

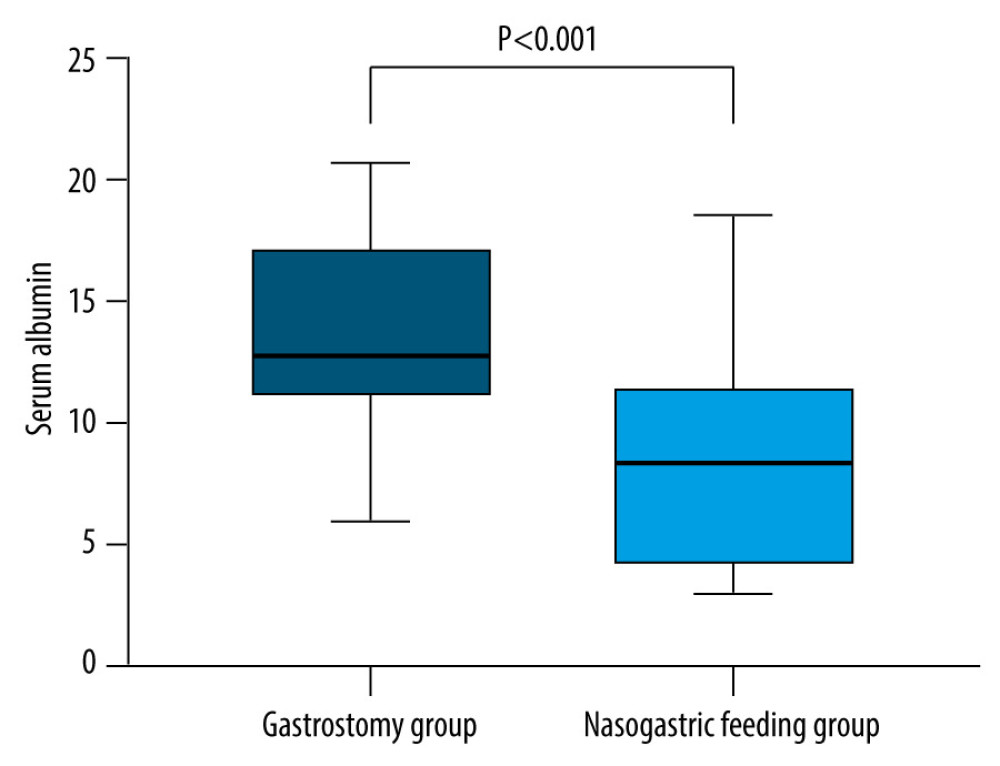

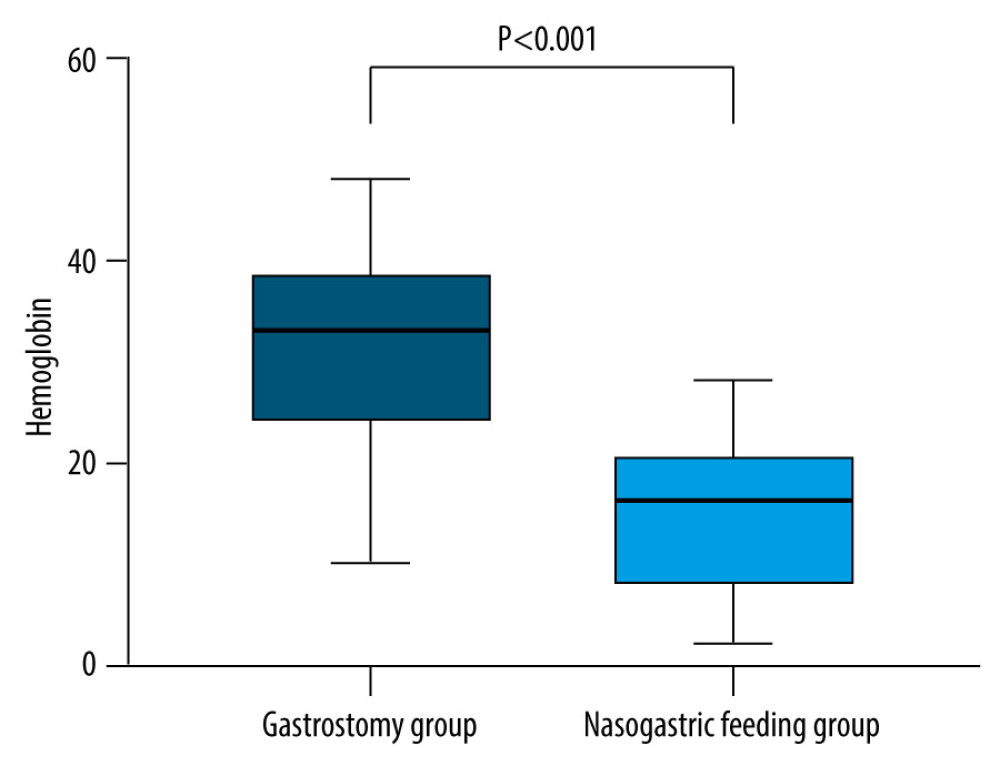

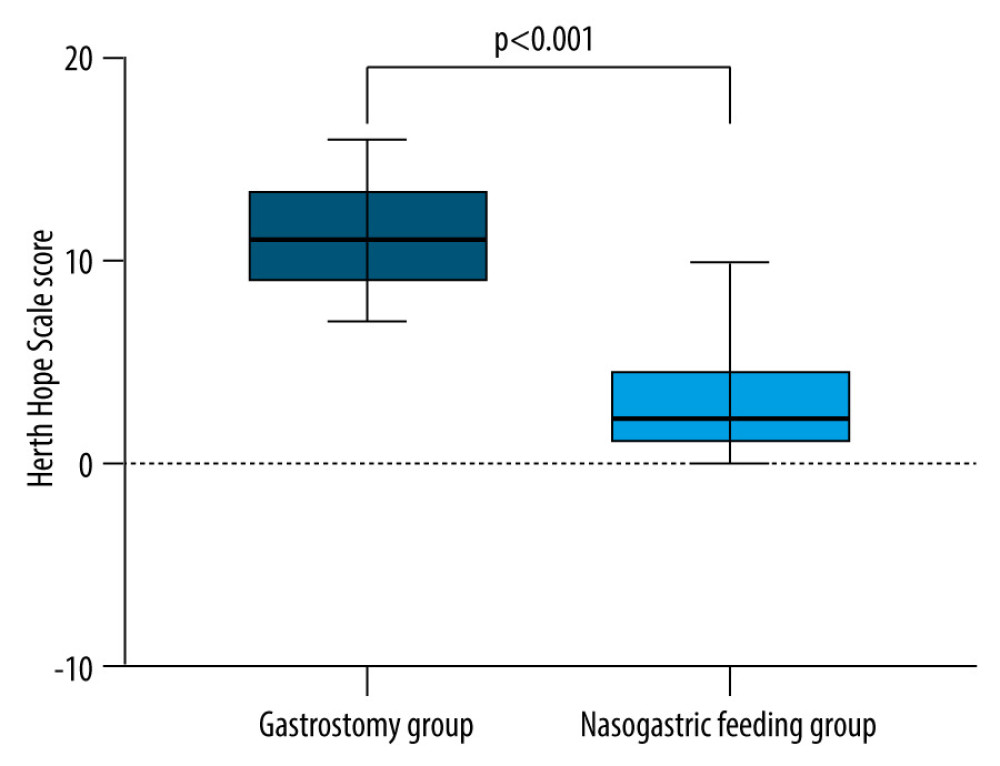

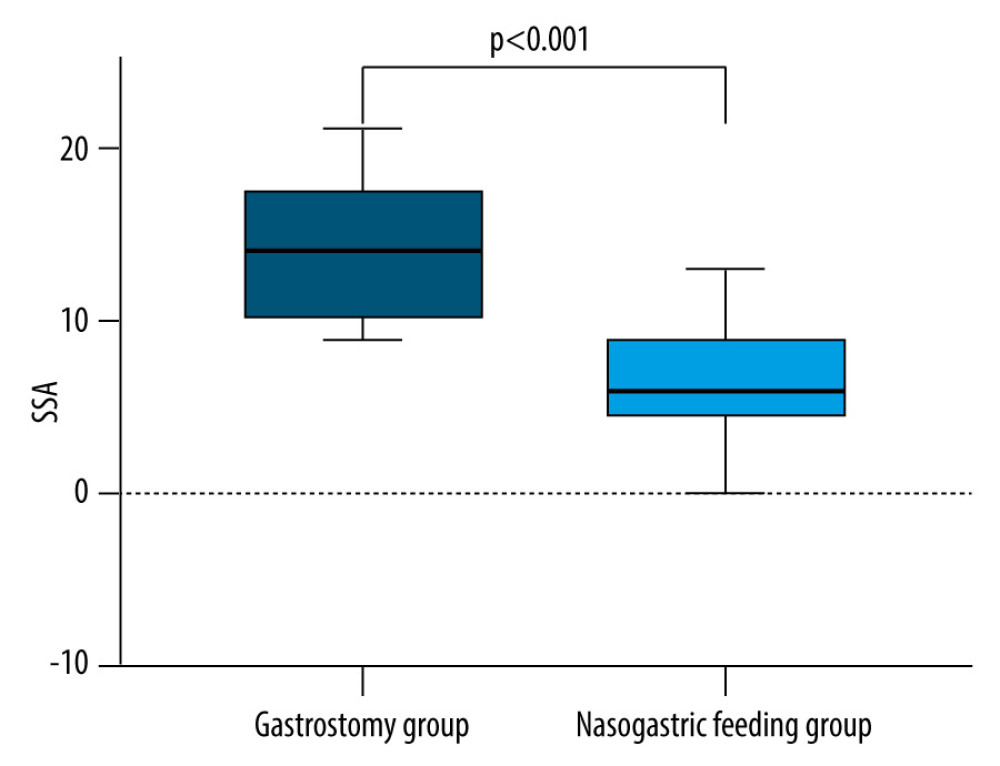

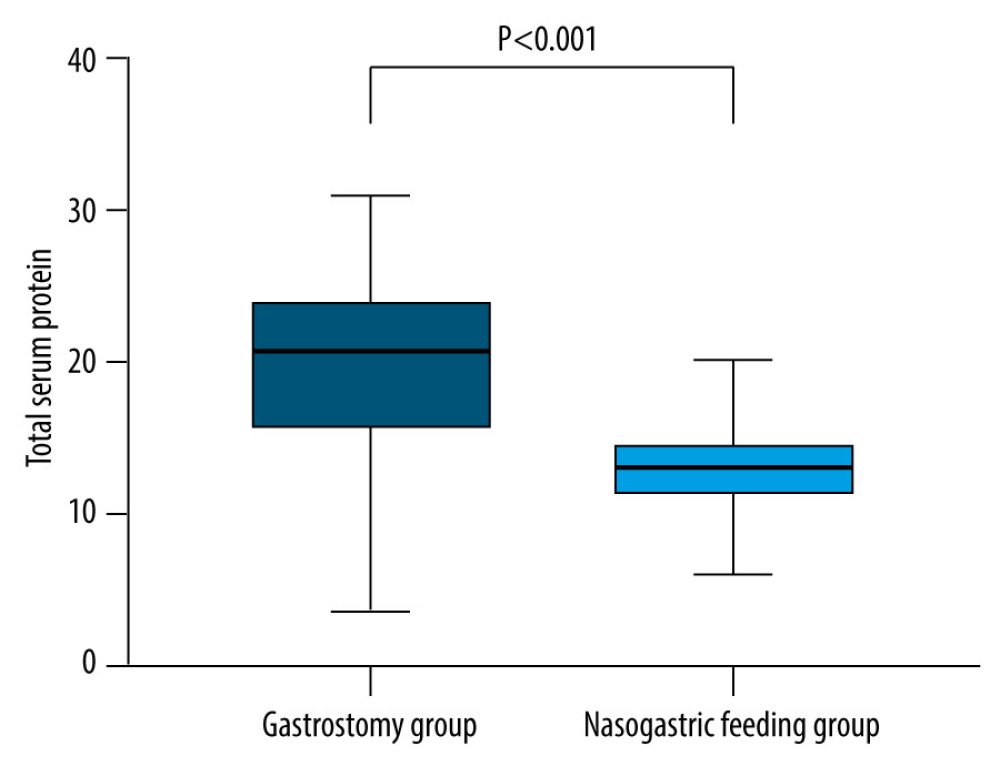

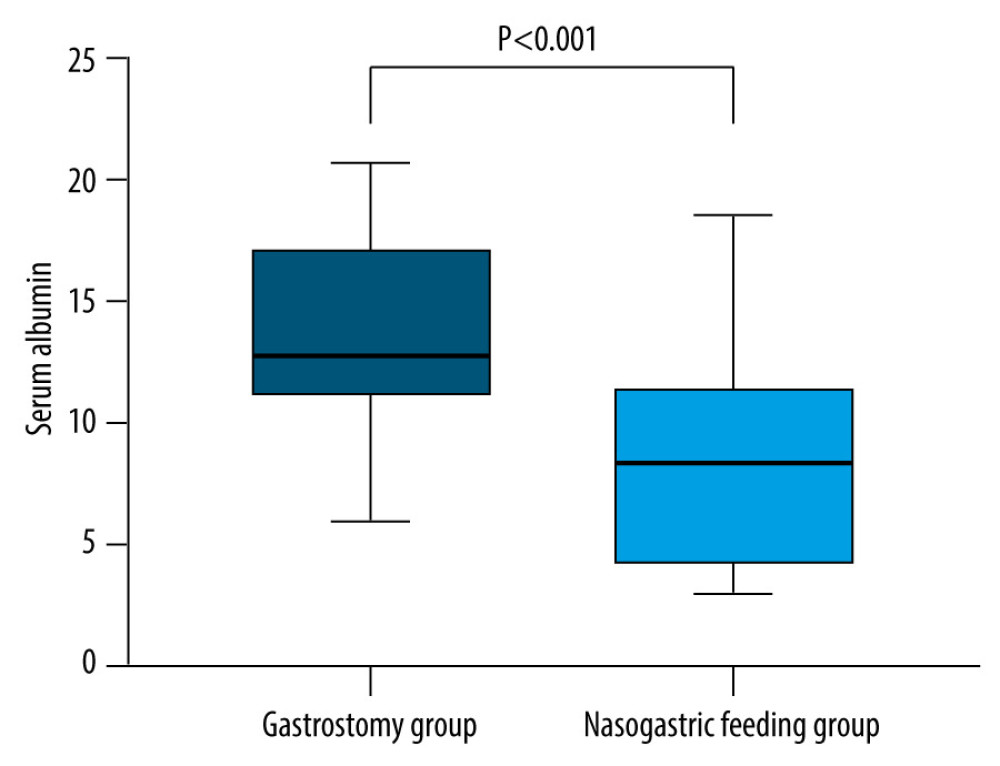

RESULTS: Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA) scores in both groups clearly decreased after the intervention, but there was greater reduction in the gastrostomy group (P<0.001). Both groups had distinct improvements of the levels of a variety of nutritional indicators after the intervention, but there was greater improvement in the gastrostomy group (P<0.001). The gastrostomy group also had fewer overall complications (P<0.001). Herth Hope Scale scores in both groups were significantly increased after intervention, and the gastrostomy group had a larger increase that the nasogastric feeding group (P<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS: Compared with nasogastric tube feeding, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy has advantages in SSA score, protein level, and Herth Hope Scale in the treatment of stroke patients with dysphagia.

Keywords: Deglutition Disorders, Gastrostomy, Intubation, Gastrointestinal, ischemic stroke, Humans, Enteral Nutrition, Stroke

Background

With the aging of society and the acceleration of urbanization, the incidence of stroke in China is also on the rise [1]. Stroke mortality is decreasing, but among survivors, dysphagia is one of the most common complications of stroke patients, with a high incidence of about 38–75% [2,3]. The central pattern generator (CPG) of swallowing is located in the area of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), the reticular formation, and the nebulous nucleus (NA) region in the rostral-lateral and ventrolateral medulla. Its network of interneurons controls the timing of the feeding phase and integrates sensory and superior afferent with efferent processes [4]. After cerebral infarction, these functional areas are damaged and swallowing function is impaired. Dysphagia can not only lead to aspiration, pneumonia, dehydration, electrolyte disorders, and nutritional disorders, which greatly increase the risk of death and poor prognosis of patients, but also greatly affect the psychological, social, daily life, and quality of life of patients [5], which means that the lack of timely and effective intervention cand greatly influence patients’ normal diet and further reduction of nutritional absorption. More severe cases of patients mistakenly inhaling food into the trachea, which further leads to life-threatening aspiration pneumonia, are likely to occur. Enteral access is achieved using bedside nasogastric tubes and nasojejunal and orogastric tubes. This can also be achieved by surgically implanting a feeding tube into the intestine, such as feeding gastrostomy (stomach) or feeding jejunostomy (jejunum) [6]. Nasogastric tubes can be used to administer nutrition or medication to patients who are unable to tolerate oral intake. Nasal feeding is a typical example of this method, which is conducive to the swallowing function along with nutritional status of patients and ensures the normal operation of intestinal function, but with certain disadvantages such as higher risk of complications and poor prognosis [7,8]. Use of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PGE) has become more common in enteral nutrition support with the rapid development medical treatment. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes are an excellent route of feeding and nutritional support for patients with a functional gastrointestinal (GI) system who require long-term enteral nutrition (usually more than 4 weeks). After local sedation, the tube is inserted and a gastrocutaneous fistula or a direct track between the anterior wall of the stomach and the abdominal wall is observed to confirm placement [9]. Given these considerations, the current study aimed to compare the outcomes of nasogastric (NG) tube feeding and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube feeding in patients with severe dysphagia following a stroke.

Material and Methods

GENERAL INFORMATION:

We enrolled 40 patients with severe dysphagia after stroke admitted to our hospital from April 2019 to December 2022. All of them were residents of Zhejiang province. They were randomly split into the gastrostomy group (20 cases) and nasogastric feeding group (20 cases).

INCLUSION CRITERIA:

1) All subjects met the diagnostic criteria for stroke in key points for diagnosis of various major cerebrovascular diseases in China 2019 [10]; 2) Confirmation by MRI or brain CT and single focus on all subjects; 3) Complicated with severe dysphagia, with evaluation of swallowing function in accordance with Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA), which mainly involves the swallowing water test, showing that its assessment content is detailed and suitable for clinical application [11]; 4) Older than age 20 years with no history of stroke.

EXCLUSION CRITERIA:

1) Patients with other cardiovascular diseases, organ dysfunction, or serious complications; 2) Patients who cannot tolerate the treatment; 3) Females pregnant or lactating; 4) Patients with abnormal or complicated nervous system diseases; 5) Patients who were lost follow-up or withdrew from the study due to personal or external factors. The consent form was signed by all the subjects and their families, as approved by the hospital Ethics Committee

RESEARCH METHODS:

All subjects were treated with standardized swallowing rehabilitation intervention after admission, including swallowing posture adjustment, changed eating habits, ice stimulation, electrical stimulation, and basic swallowing training. Each patient had a rehabilitation plan formulated by a rehabilitation doctor, and different or combined rehabilitation measures were adopted according to the severity of the patient’s condition.

Nasogastric feeding and gastrostomy were equally applicable in all patients, who were randomly assigned to 1 of the 2 groups. In the nasogastric feeding group, patients could be given a cup of water with a straw to help the tube pass through smoothly. The catheter was advanced with firm, constant pressure while the patient sips. In patients who were intubated, we used the reverse Sellick maneuver (ie, pulling the thyroid cartilage up instead of pushing it down during intubation) and a frozen nasogastric tube helped facilitate intubation. Once the catheter was inserted to the appropriate length, usually around 55 cm, it was secured to the patient’s nose with tape [12]. The patients in the endoscopic gastrostomy group were treated with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. After the subjects were placed in supine position with the assistance of an endoscope, the gastroscope was inserted into the gastric cavity, and appropriate gas was injected to expand the gastric cavity to ensure that the abdominal wall was completely attached to the anterior wall of the stomach. The ideal puncture site was selected. The puncture needle with the core removed was routinely sterilized together with the gastric tube and placed in the stomach, and the guide wire was inserted into the gastric cavity along the cannula. The guide wire was then clamped with biopsy forceps and removed from the esophagus under direct vision of the gastroscope. Then, the guide wire and gastroscope were retracted to ensure the appropriate connection between the guide wire ring and the stoma tube. After observation to confirm the gastric fixation disc was close to the gastric wall, the gastrostomy tube was fixed [13].

The discrepancies of swallowing function, nutritional recovery, safety, and hope level between the 2 groups were analyzed along with the evaluation of the swallowing function in accordance with the swallowing function assessment scale (SSA), with a total score of 46. The SSA method consisted of 3 parts: (1) Clinical examination, including consciousness, head and trunk control, breathing, lip closure, soft-palate movement, laryngeal function, pharyngeal reflexes, and spontaneous cough, with a total score of 8–23; (2) Patients were asked to swallow 5 ml of water 3 times, and the laryngeal movement, repeated swallowing, stridor during swallowing, and laryngeal function after swallowing were observed, with total score 5–11; (3) If there was no abnormality as mentioned above, the patient was asked to swallow 60 ml of water, and the time needed to swallow and the presence or absence of cough were observed, with a total score of 5–12. The scale has a minimum score of 18 and a maximum score of 46, with higher scores indicating poorer swallowing function. A trained rehabilitation physician evaluated the patients and completed a record form [11].

All subjects received standardized swallowing rehabilitation intervention after admission, including swallowing posture adjustment, changing dietary habits, ice stimulation, electrical stimulation, and basic swallowing training. Rehabilitation plans were made by rehabilitation doctors for each patient, and different or combined rehabilitation measures were adopted according to the severity of the patient’s condition.

The level of nutritional indicators, including serum total protein, serum albumin and hemoglobin, has enabled the conduct of such evaluation upon nutritional recovery. The main complications encompass gastrointestinal bleeding, reflux esophagitis and aspiration pneumonia.

The evaluation of hope level is dependent mainly on the Herth Hope Scale [14], which covers the following 4 dimensions: 1) positive attitude, 2) positive action, 3) intimate relationship, and 4) overall hope. Swallowing function, nutritional recovery, and hope level were assessed 1 day before the intervention and 1 month after the intervention.

CLINICAL DATA COLLECTION:

Detailed medical history-taking, medication history-taking, and physical examinations were completed for all patients. Clinical data included age, gender, smoking history, drinking history, and blood pressure. total protein level, serum albumin level, and hemoglobin protein level.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The selected patients were all long-term hospitalized rehabilitation patients, and the clinical data were collected from the electronic health records. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (International Business Machines Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Patient characteristics were described with frequencies (percentages) or mean±standard deviation values. Significant differences between groups were assessed by one-way analysis of variance. The chi-squared test was used for count data. Figures were drawn using the SPSS Statistics (International Business Machines Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) software programs.

Results

THE NUTRITIONAL INDICATORS OF THE 2 GROUPS WERE COMPARED BEFORE AND AFTER TREATMENT:

After treatment, the total protein level of the gastrostomy group and the nasogastric feeding group increased, and the gastrostomy group showed a greater increase than the nasogastric feeding group (mean difference [7.243±1.610]; 95% CI [3.988–10.50], P<0.001) shown in Figure 2.

The level of albumin in the gastrostomy group and the nasal feeding group increased after treatment, and the increase in the gastrostomy group was more significant than that in the nasal feeding group (mean difference [5.281±1.268]; 95% CI [2.718–7.844], P<0.001), shown in Figure 3.

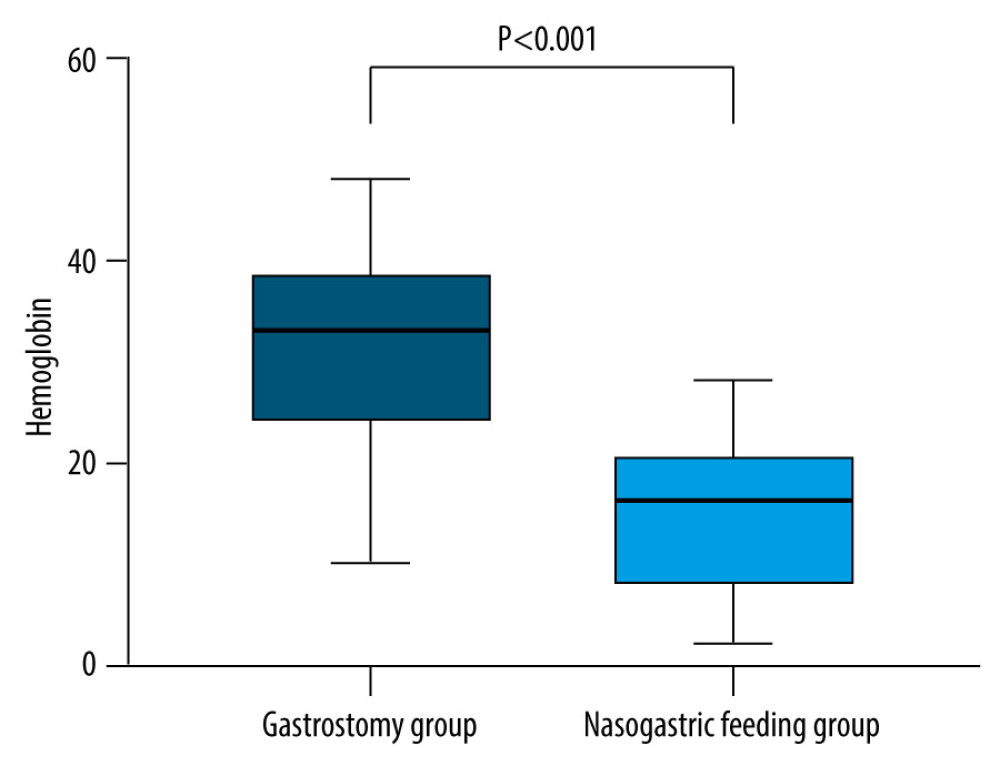

The level of hemoglobin in the gastrostomy group and the nasogastric feeding group increased after treatment, and the increase in the gastrostomy group was more significant than that in the nasogastric feeding group (mean difference [16.05±2.803]; 95% CI [10.38–27.71], P<0.001), shown in Figure 4.

COMPLICATIONS OF THE 2 GROUPS:

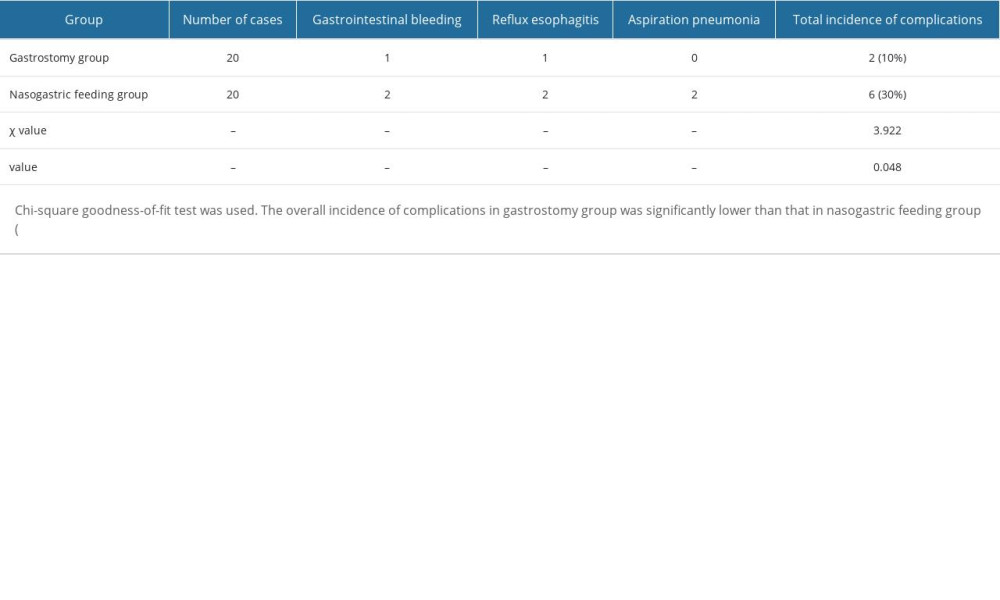

The chi-square goodness-of-fit test showed the overall incidence of complications in the gastrostomy group was significantly lower than that in the nasogastric feeding group (P<0.05), as illustrated in Table 2.

THE HERTH HOPE SCALE SCORES OF THE 2 GROUPS BEFORE AND AFTER INTERVENTION WERE COMPARED:

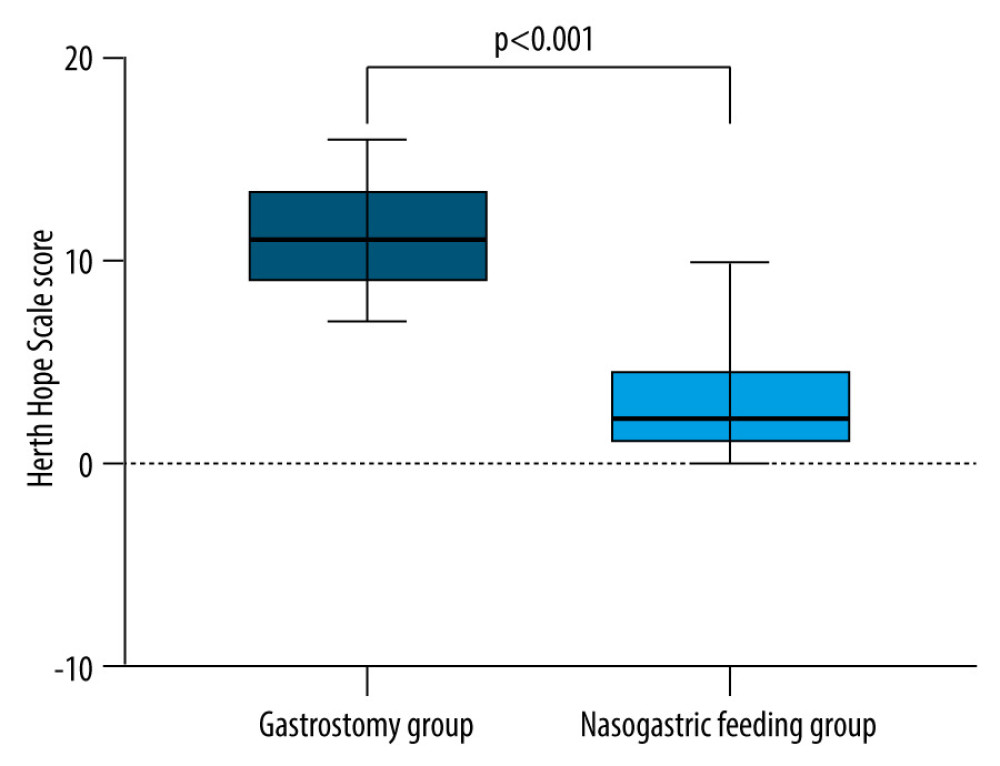

The Herth Hope Scale scores of the gastrostomy group and the nasal feeding group increased on average after treatment, and the gastrostomy group increased more significantly than the nasal feeding group (mean difference [8.714±0.8779]; 95% CI [6.94–10.49], P<0.001), as revealed in Figure 5.

Discussion

The SSA scores of the 2 groups were significantly reduced after the intervention, but the change was greater in the gastrostomy group. Nutritional indexes of the 2 groups were markedly improved after the intervention, but the improvement in the gastrostomy group greater. Our results may be related to the following mechanisms. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy can provide appropriate mechanical stimulation to the gastrointestinal tract and give sufficient energy for patients, promote the enhancement of intestinal mucosal metabolism, and maintain and increase the blood flow of the intestine and liver, and thereby help to maintain the normal function of the mucosal barrier and endothelial system, avoiding the translocation of bacteria and endotoxin in the intestines [15,16]. Additionally, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is minimally invasive, which befits patients with dysphagia and can reduce nasopharyngeal gastric tube stimulation, ensuring a lower risk of related complications. Combined with the above findings, the reliability of our study was further confirmed.

In our study, through the comparative determination of serum albumin, total protein, and hemoglobin levels of patients, we found that the gastrostomy group performed significantly better than the nasal feeding group. Dysphagia, one of the most common complications of stroke, is mainly referred as the damage of swallowing organs like mandible, tongue, throat, and esophageal sphincter, which incurs difficulties in food’s motion into the stomach through the oral cavity and seriously affects the prognosis of patients [17–19]. There is a high incidence of complications such as dehydration, malnutrition, and aspiration pneumonia in severe dysphagia among stroke patients, which drastically increase the mortality of patients and cause serious adverse consequences [20–22]. The above studies also confirmed the results of our study, showing that regardless of which parenteral nutrition method is used in stroke patients with dysphagia, the nutritional level will be improved. An active and effective intervention to ensure the daily intake of nutrients will improve the nutritional status, promoting disease stability, and improving the prognosis.

Based on parenteral nutrition, standardized swallowing rehabilitation training is also very important for such patients, since repetitive training can effectively stimulate the central nervous system of patients, and hence promote the reestablishment of motor projection area, regain the lost motor function, and enhance autonomous muscle movement, which improves swallowing function [23–25]. After admission, the patients were given standardized swallowing rehabilitation intervention, including swallowing posture adjustment, changing dietary habits, ice stimulation, electrical stimulation, and basic swallowing training [26]. The first is swallowing posture adjustment. One of the most commonly used postural adjustments is a 45-degree chin tilt, which is a simple intervention that protects the airway by slowing the delivery of a bolus and thereby delaying the time to “trigger” the pharyngeal movement during swallowing [27]. Second, changing dietary habits can help patients with dysphagia after stroke to eat more safely to prevent the occurrence of aspiration and increase caloric intake. In some patients with dysphagia, a particular amount of food triggers the most rapid pharyngeal movement with each swallow [28]. Thirdly, ice stimulation, usually by pricking with iced cotton sticks or gargling with ice water, is a compensatory treatment to restore swallowing function. The specific methods include stimulating the palatoglossus arch, tongue body, soft and hard palate, pharyngeal wall, oral mucosa, and muscles with iced cotton sticks before eating and swallowing, or cleaning the mouth with cold water to enhance the oral sensation, thereby improving sensitivity of the swallowing reflex and attention during swallowing, and promoting the rehabilitation of swallowing function [29]. Fourth, neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is used as an adjunctive therapy by placing the upper electrode on the hyoid muscle directly above the hyoid bone and the lower electrode horizontally on the thyrohyoid bone. Stimulation intensity levels starting at 2 mA and increasing at 0.5-mA intervals gradually increase the stimulation effect, and studies have shown that adding NMES therapy to traditional manipulation provides additional benefits in some diseases related to swallowing [30,31]. Finally, electrical stimulation, low-frequency electrical stimulation, and medium-frequency electrical stimulation are commonly used in the treatment of dysphagia. In clinical practice, low-frequency electrical stimulation is the main electrical stimulation method used for clinical treatment of dysphagia. The mechanism of action of the 2 therapeutic devices is the same, which is to stimulate the patient’s swallowing-related muscle groups by electrical stimulation, facilitate muscle contraction, enhance the strength and speed of pharyngeal muscle contraction, help the uplift of the larynx, and promote the timely and sequential increase of sensory feedback [32]. Despite the benefits of rehabilitation training in stabilizing the patient’s condition, nutrition acquired by mouth does is insufficient and effective enteral nutrition support may be crucial.

This study found that the overall incidence of complications in the gastrostomy group was markedly lower than that in the nasogastric feeding group. Although our sample size is small and consistent with the conclusions of previous studies [33], our team considered the following reasons for gastrostomy complications in combination with clinical manifestations, which is due to the relatively small stimulation to the patients and the retaining of the anti-reflux ability of the lower esophagus and cardia to the greatest extent in the gastrostomy group. In addition, blockage, catheter shedding, and subjective failure are likely to occur due to the small diameter of the nasogastric feeding tube, and the nutritional support mode affects the function of the lower cardiac sphincter of patients, increasing the risk of reflux esophagitis and aspiration, which harm the prognosis of patients. The larger diameter of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy catheter helps avoid complications and improves the prognosis of patients.

The Herth Hope Scale results in the gastrostomy group were significantly better than in the gastric tube group confirming its role in enhancing the confidence and hope of patients to overcome the disease.

Through SSA score, protein level, and Herth hope index, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy has advantages. Similarly, through our study, we inform the Chinese doctors that the results of the Chinese race research are basically the same as the results of the European and American race research, and there is no regional and racial difference. When encountering cerebral infarction patients with swallowing function, we should try to persuade the patients to direct gastrostomy instead of giving priority to gastric tube and nasal feeding.

However, there are still limitations in this study such as its small sample size, leading to the omission of some factors. In addition, nutritionists will choose different composition ratios of nutrient solutions according to patients, and the source and proportion of protein, carbohydrate, and fat are mainly considered when selecting formulas. The content of dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals in each formula is also different, so the present study lacks comparative analysis of nutrient intake, which may have biased our results. Therefore, a follow-up study is required to expand the scale, prolong the observation time, and eliminate confounding factors for better accuracy of the results.

Conclusions

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy can improve the swallowing function of stroke patients with severe dysphagia. SSA score, protein level, and Herth hope index show the advantages of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Figures

Figure 1. Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA) score in the gastrostomy group decreased more than that in the nasal feeding groupA drastic decrease occurred in the SSA scores of the 2 groups before and after the intervention, and the gastrostomy group performed better than the nasal feeding group (all P<0.05).

Figure 1. Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA) score in the gastrostomy group decreased more than that in the nasal feeding groupA drastic decrease occurred in the SSA scores of the 2 groups before and after the intervention, and the gastrostomy group performed better than the nasal feeding group (all P<0.05).  Figure 2. The increase of total protein level in the gastrostomy group was significantly better than that in the nasal feeding groupThe total protein level increased in both groups, and the total protein level increased more significantly in the gastrostomy group than in the nasogastric feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).

Figure 2. The increase of total protein level in the gastrostomy group was significantly better than that in the nasal feeding groupThe total protein level increased in both groups, and the total protein level increased more significantly in the gastrostomy group than in the nasogastric feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).  Figure 3. The level of albumin in the gastrostomy group was significantly higher than that in the nasal feeding groupAlbumin levels were increased in both groups, and the total protein levels in the gastrostomy group increased more significantly than in the nasogastric feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).

Figure 3. The level of albumin in the gastrostomy group was significantly higher than that in the nasal feeding groupAlbumin levels were increased in both groups, and the total protein levels in the gastrostomy group increased more significantly than in the nasogastric feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).  Figure 4. The increase of hemoglobin level in the gastrostomy group was significantly better than that in the nasal feeding groupThe hemoglobin level increased in both groups, and the total protein level increased more significantly in the gastrostomy group and the nasal feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).

Figure 4. The increase of hemoglobin level in the gastrostomy group was significantly better than that in the nasal feeding groupThe hemoglobin level increased in both groups, and the total protein level increased more significantly in the gastrostomy group and the nasal feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).  Figure 5. The Herth Hope Scale score in the gastrostomy group decreased more than that in the nasal feeding groupHope Scale scores of the 2 groups before and after intervention were compared. The Herth Hope index scores of the 2 groups were significantly improved after intervention, and the degree of improvement in the gastrostomy group was better than that of the gastrostomy group (all P<0.05).

Figure 5. The Herth Hope Scale score in the gastrostomy group decreased more than that in the nasal feeding groupHope Scale scores of the 2 groups before and after intervention were compared. The Herth Hope index scores of the 2 groups were significantly improved after intervention, and the degree of improvement in the gastrostomy group was better than that of the gastrostomy group (all P<0.05). References

1. Ma LY, Chen WW, Gao RL, China cardiovascular diseases report 2018: An updated summary: J Geriatr Cardiol, 2020; 17(1); 1-8

2. Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, Dysphagia after stroke: Incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications: Stroke, 2005; 36(12); 2756-63

3. Carnaby GD, LaGorio L, Silliman S, Crary M, Exercise-based swallowing intervention (McNeill Dysphagia Therapy) with adjunctive NMES to treat dysphagia post-stroke: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial: J Oral Rehabil, 2020; 47(4); 501-10

4. Prosiegel M, Höling R, Heintze M, The localization of central pattern generators for swallowing in humans – a clinical-anatomical study on patients with unilateral paresis of the vagal nerve, Avellis’ syndrome, Wallenberg’s syndrome, posterior fossa tumours and cerebellar hemorrhage: Acta Neurochir Suppl, 2005; 93; 85-88

5. Robbins J, Langmore S, Hind JA, Erlichman M: J Rehabil Res Dev, 2002; 39(4); 543-48

6. Adeyinka A, Rouster AS, Valentine M, Enteric feedings: StatPearls December 26, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

7. Sabbouh T, Torbey MT, Malnutrition in stroke patients: Risk factors, assessment, and management: Neurocrit Care, 2018; 29(3); 374-84

8. Bahat G, Tufan F, Tufan A, Karan MA, The ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition-geriatrics: Need for its promotion in practice: Clin Nutr, 2016; 35(4); 985

9. Vudayagiri L, Hoilat GJ, Gemma R, Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube: StatPearls August 14, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

10. Wang Y, Jing J, Meng X, The Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR-III) for patients with acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack: Design, rationale and baseline patient characteristics: Stroke Vasc Neurol, 2019; 4(3); 158-64

11. Eltringham SA, Kilner K, Gee M, Factors associated with risk of stroke-associated pneumonia in patients with dysphagia: A systematic review: Dysphagia, 2020; 35(5); 735-44

12. Sigmon DF, An J, Nasogastric tube: StatPearls October 31, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

13. Grant JP, Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Initial placement by single endoscopic technique and long-term follow-up: Ann Surg, 1993; 217(2); 168-74

14. Herth K, Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation: J Adv Nurs, 1992; 17(10); 1251-59

15. Brown K, Cai C, Barreto A, Predictors of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement in acute ischemic stroke: J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2018; 27(11); 3200-7

16. Klose J, Heldwein W, Rafferzeder M, Nutritional status and quality of life in patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in practice: prospective one-year follow-up: Dig Dis Sci, 2003; 48(10); 2057-63

17. Eltringham SA, Kilner K, Gee M, Factors associated with risk of stroke-associated pneumonia in patients with dysphagia: A systematic review: Dysphagia, 2020; 35(5); 735-44

18. Souza JT, Ribeiro PW, de Paiva SAR, Dysphagia and tube feeding after stroke are associated with poorer functional and mortality outcomes: Clin Nutr, 2020; 39(9); 2786-92

19. Juan W, Zhen H, Yan-Ying F, A comparative study of two tube feeding methods in patients with dysphagia after stroke: A randomized controlled trial: J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2020; 29(3); 104602

20. Dwolatzky T, Berezovski S, Friedmann R, A prospective comparison of the use of nasogastric and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes for long-term enteral feeding in older people: Clin Nutr, 2001; 20(6); 535-40

21. Langmore SE, Dysphagia in neurologic patients in the Intensive Care Unit: Semin Neurol, 1996; 16(4); 329-40

22. Ohta R, Weiss E, Mekky M, Sano C, Relationship between dysphagia and home discharge among older patients receiving hospital rehabilitation in rural Japan: A retrospective cohort study: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022; 19(16); 10125

23. Xia W, Zheng C, Zhu S, Tang Z, Does the addition of specific acupuncture to standard swallowing training improve outcomes in patients with dysphagia after stroke? A randomized controlled trial: Clin Rehabil, 2016; 30(3); 237-46

24. Athukorala RP, Jones RD, Sella O, Huckabee ML, Skill training for swallowing rehabilitation in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2014; 95(7); 1374-82

25. Byeon H, Effect of simultaneous application of postural techniques and expiratory muscle strength training on the enhancement of the swallowing function of patients with dysphagia caused by Parkinson’s disease: J Phys Ther Sci, 2016; 28(6); 1840-43

26. Tan Z, Wei X, Tan C, Effect of neuromuscular electrical stimulation combined with swallowing rehabilitation training on the treatment efficacy and life quality of stroke patients with dysphagia: Am J Transl Res, 2022; 14(2); 1258-67

27. Ney DM, Weiss JM, Kind AJ, Robbins J, Senescent swallowing: Impact, strategies, and interventions: Nutr Clin Pract, 2009; 24(3); 395-413

28. Garcia JM, Chambers E, Managing dysphagia through diet modifications: Am J Nurs, 2010; 110(11); 26-35

29. Wirth R, Dziewas R, Beck AM, Oropharyngeal dysphagia in older persons – from pathophysiology to adequate intervention: A review and summary of an international expert meeting: Clin Interv Aging, 2016; 11; 189-208

30. Zhang Q, Wu S, Effects of Synchronized Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES) on the submental muscles during ingestion of a specified volume of soft food in patients with mild-to-moderate dysphagia following stroke: Med Sci Monit, 2021; 27; e928988

31. Byeon H, Combined Effects of NMES and Mendelsohn Maneuver on the swallowing function and swallowing-quality of life of patients with stroke-induced sub-acute swallowing disorders: Biomedicines, 2020; 8(1); 12

32. Leelamanit V, Limsakul C, Geater A, Synchronized electrical stimulation in treating pharyngeal dysphagia: Laryngoscope, 2002; 112(12); 2204-10

33. Grant JP, Comparison of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with Stamm gastrostomy: Ann Surg, 1988; 207(5); 598-603

Figures

Figure 1. Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA) score in the gastrostomy group decreased more than that in the nasal feeding groupA drastic decrease occurred in the SSA scores of the 2 groups before and after the intervention, and the gastrostomy group performed better than the nasal feeding group (all P<0.05).

Figure 1. Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA) score in the gastrostomy group decreased more than that in the nasal feeding groupA drastic decrease occurred in the SSA scores of the 2 groups before and after the intervention, and the gastrostomy group performed better than the nasal feeding group (all P<0.05). Figure 2. The increase of total protein level in the gastrostomy group was significantly better than that in the nasal feeding groupThe total protein level increased in both groups, and the total protein level increased more significantly in the gastrostomy group than in the nasogastric feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).

Figure 2. The increase of total protein level in the gastrostomy group was significantly better than that in the nasal feeding groupThe total protein level increased in both groups, and the total protein level increased more significantly in the gastrostomy group than in the nasogastric feeding group after treatment (P<0.05). Figure 3. The level of albumin in the gastrostomy group was significantly higher than that in the nasal feeding groupAlbumin levels were increased in both groups, and the total protein levels in the gastrostomy group increased more significantly than in the nasogastric feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).

Figure 3. The level of albumin in the gastrostomy group was significantly higher than that in the nasal feeding groupAlbumin levels were increased in both groups, and the total protein levels in the gastrostomy group increased more significantly than in the nasogastric feeding group after treatment (P<0.05). Figure 4. The increase of hemoglobin level in the gastrostomy group was significantly better than that in the nasal feeding groupThe hemoglobin level increased in both groups, and the total protein level increased more significantly in the gastrostomy group and the nasal feeding group after treatment (P<0.05).

Figure 4. The increase of hemoglobin level in the gastrostomy group was significantly better than that in the nasal feeding groupThe hemoglobin level increased in both groups, and the total protein level increased more significantly in the gastrostomy group and the nasal feeding group after treatment (P<0.05). Figure 5. The Herth Hope Scale score in the gastrostomy group decreased more than that in the nasal feeding groupHope Scale scores of the 2 groups before and after intervention were compared. The Herth Hope index scores of the 2 groups were significantly improved after intervention, and the degree of improvement in the gastrostomy group was better than that of the gastrostomy group (all P<0.05).

Figure 5. The Herth Hope Scale score in the gastrostomy group decreased more than that in the nasal feeding groupHope Scale scores of the 2 groups before and after intervention were compared. The Herth Hope index scores of the 2 groups were significantly improved after intervention, and the degree of improvement in the gastrostomy group was better than that of the gastrostomy group (all P<0.05). Tables

Table 1. Detailed clinical information of patients in the gastrostomy group and nasogastric feeding group (mean±SD).

Table 1. Detailed clinical information of patients in the gastrostomy group and nasogastric feeding group (mean±SD). Table 2. Complications of 2 groups (n, %).

Table 2. Complications of 2 groups (n, %). Table 1. Detailed clinical information of patients in the gastrostomy group and nasogastric feeding group (mean±SD).

Table 1. Detailed clinical information of patients in the gastrostomy group and nasogastric feeding group (mean±SD). Table 2. Complications of 2 groups (n, %).

Table 2. Complications of 2 groups (n, %). In Press

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparing Neuromuscular Blockade Measurement Between Upper Arm (TOF Cuff®) and Eyelid (TOF Scan®) Using Miv...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943630

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952