13 August 2023: Clinical Research

Meeting Patient Expectations: Assessing Medical Service and Quality of Care Using the SERVQUAL Model in Dermatology Patients at a Single Center in Poland

Aleksandra JonkiszDOI: 10.12659/MSM.941007

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e941007

Abstract

BACKGROUND: This study applied the SERVQUAL model, a widely recognized tool for assessing the quality of services, to understand the gap between patient expectations and perceptions of care quality among 413 dermatology patients at a single medical center in Poland.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The study cohort included 413 patients: 195 inpatients and 218 outpatients. The SERVQUAL model’s 5 dimensions – reliability, assurance, tangibility, empathy, and responsiveness, each including multiple specific items – served as our assessment criteria. Patient responses to these items measured the perceived and expected quality of service. The service quality index (SQ), calculated as the difference between perception and expectation ratings, was the study’s primary outcome measure. A negative SQ score was interpreted as patient dissatisfaction.

RESULTS: The study results showed a negative SQ score, which signified a discrepancy between high patient expectations and the actual perceived quality of service. The largest gap was seen in the tangibility dimension. Differences emerged based on treatment setting, with inpatient and outpatient settings showing varying expectations and perceptions. Patient sex and residential location also influenced the tangibility dimension. Employed patients and patients with diminished quality of life had heightened expectations in certain dimensions, while patients below 36 years of age expressed higher expectations in responsiveness, assurance, and empathy.

CONCLUSIONS: The findings emphasize the critical role of care quality in shaping patients’ satisfaction and perception, particularly in dermatology. Using the SERVQUAL model, this study identified the tangibility dimension as an area needing improvement. This insight serves as a stepping stone toward enhancing patient satisfaction by addressing these unmet expectations.

Keywords: Attitude, Delivery of Health Care, Dermatology, Inpatients, Outpatients, Quality of Health Care, Humans, Motivation, Reproducibility of Results, Poland, Quality of Life, Surveys and Questionnaires, Patient Satisfaction

Background

Every medical procedure should be conducted with attention to its quality and compliance with the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline standards of medical practice and performed with consideration of patient acceptance and highest satisfaction [1]. Medical procedures should also meet the expectations of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) guidelines [2]. The highest possible level of service quality should be maintained irrespective of medical specialty and/or the setting where the services are provided (inpatient or outpatient). The WHO places particular emphasis on the importance of quality in the delivery of health services. Unrestricted access to high-quality care for the general public is advocated as a means to achieve sustainability [3].

The clinical quality provided and perceived quality are the 2 domains of quality in medical procedures. Clinical quality refers to the perception of the medical staff of their job, namely, to their awareness that the services they provide are of the highest possible quality and performed in the best possible way [4,5].

For a patient, the perceived quality, i.e., the subjective feelings of empathy and rapport during a stay at a medical unit, is an important element in the perception of the quality of the overall care received. In addition, the importance of the perception of competence, professionalism of the staff, and aesthetics and ergonomics of the facility should be emphasized, all of which contribute to the overall impression the patients have [4].

The rapidly developing management of medical services has been taking place due to the transformation of the non-medical service market, which includes various industries [6]. Today, the observation that the quality of a provided service is the result between the quality expected and the quality received is well established. The SERVQUAL model has been developed on this foundation to assess service quality based on standardized parameters [7,8].

In the field of service quality assessment, the SERVQUAL model has emerged as a prominent and valuable tool. The SERVQUAL method, an acronym from the words “service” and “quality”, was developed by Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry in the 1980s [9] to help organizations measure and manage customer perceptions of service quality. This comprehensive framework encompasses a set of 5 dimensions that are instrumental in assessing and improving service quality: reliability (5 items), assurance (4 items), tangibility (4 items), empathy (5 items), and responsiveness (4 items). It also known as the RATER (reliability-assurance-tangibility-empathy-responsiveness) model.

At the base of the SERVQUAL model is the assumption that there are gaps (discrepancies) between the service provided and the service level expected by the purchaser (customer). Identifying such gaps provides an opportunity to implement changes that affect the level of expectations from the service provided. It results in an improvement in the quality of the service and, consequently, in increased customer satisfaction [10,11]. Applying the SERVQUAL gap model allows the quality of the service provided to be captured in a measurable way. Therefore, it is widely used to survey customer satisfaction levels in various areas, including in medical and therapeutic sectors [12,13].

On the one hand, the SERVQUAL method makes it possible to identify patient expectations, while on the other, it enables the service provider to recognize anomalies, if any, and introduce corrective measures, where applicable. Furthermore, SERVQUAL enables medical managers to modify the elements of selected medical procedures. This improves the quality of services provided, thereby increasing patient satisfaction and improving the functioning of the healthcare provider themselves [14].

The SERVQUAL model has also been applied in recent research projects on implementing information and communication systems effectively in medicine. This can be greatly beneficial in healthcare, including in the quality of care assessments, patient position, costs incurred, and mindset of healthcare professionals [15]. The SERVQUAL model is also used to assess the quality of medical services provided in private and public sectors, taking into account the determinants of the assessment rates, as expressed by patients [16–18].

Service quality, which is understood as an objective goal to be pursued when providing care for human health, requires the highest quality at every level [19,20]. However, in terms of the level of their quality, medical services are sometimes perceived differently by patients. The discrepancies observed among patient assessments depend mainly on personal factors, such as sex, age, education, employment status, financial status, and place of residence. It also depends on the clinical status of disease progression and the presence of comorbidities [21]. According to van Hoff et al [22], patient satisfaction can also be dictated by the type of treatment provided in an open (outpatient) or closed (hospital) setting. There is still a lack of reliable research on assessing patient satisfaction with the level of health services provided in the field of dermatology.

Therefore, this study included 413 dermatology patients at a single center in Poland and aimed to evaluate how patient expectations were met in terms of medical service and quality of care according to the SERVQUAL model.

Material and Methods

ETHICS APPROVAL:

The patients participating in the study were informed of the specific goals and conduct of the study and gave informed consent to their participation. A standardized questionnaire form was used as the primary research tool in the study. The study design was accepted and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University in Lublin (permission no. KE–0254/141/2019). All patients gave verbal informed consent to take part in the study and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any stage. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the patients were assured of complete anonymity. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines [23]. In addition, the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were followed owing to the observational study design [24].

STUDY DESIGN AND POPULATION:

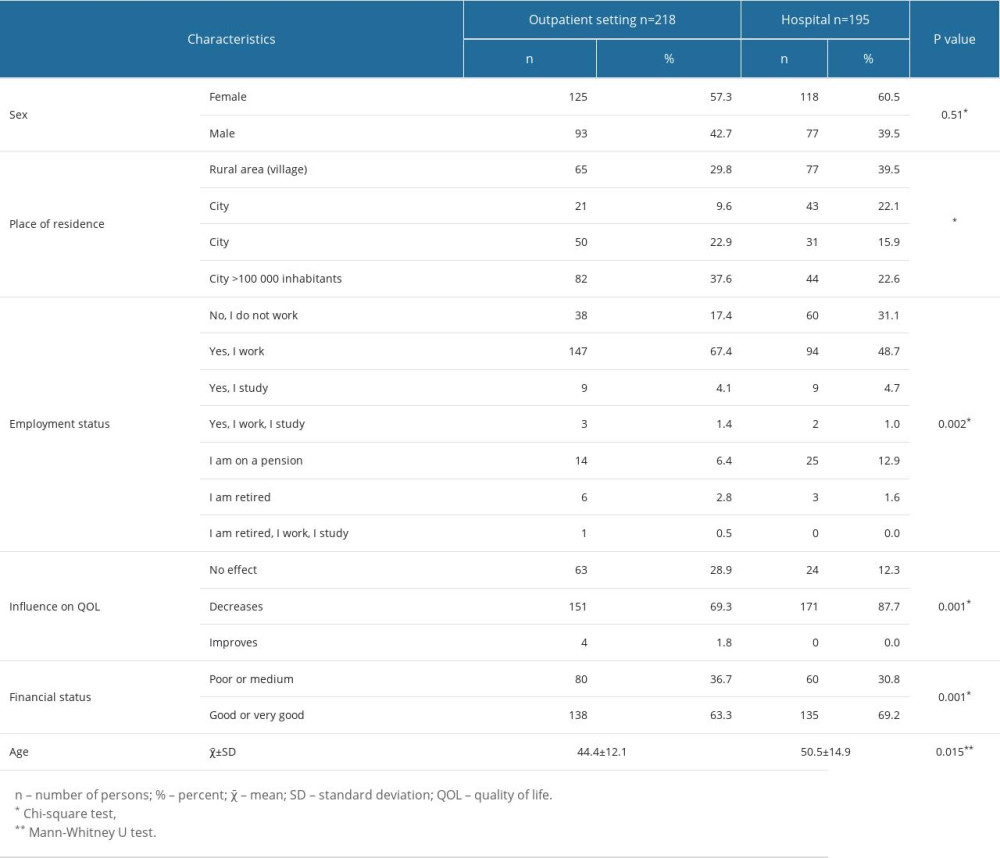

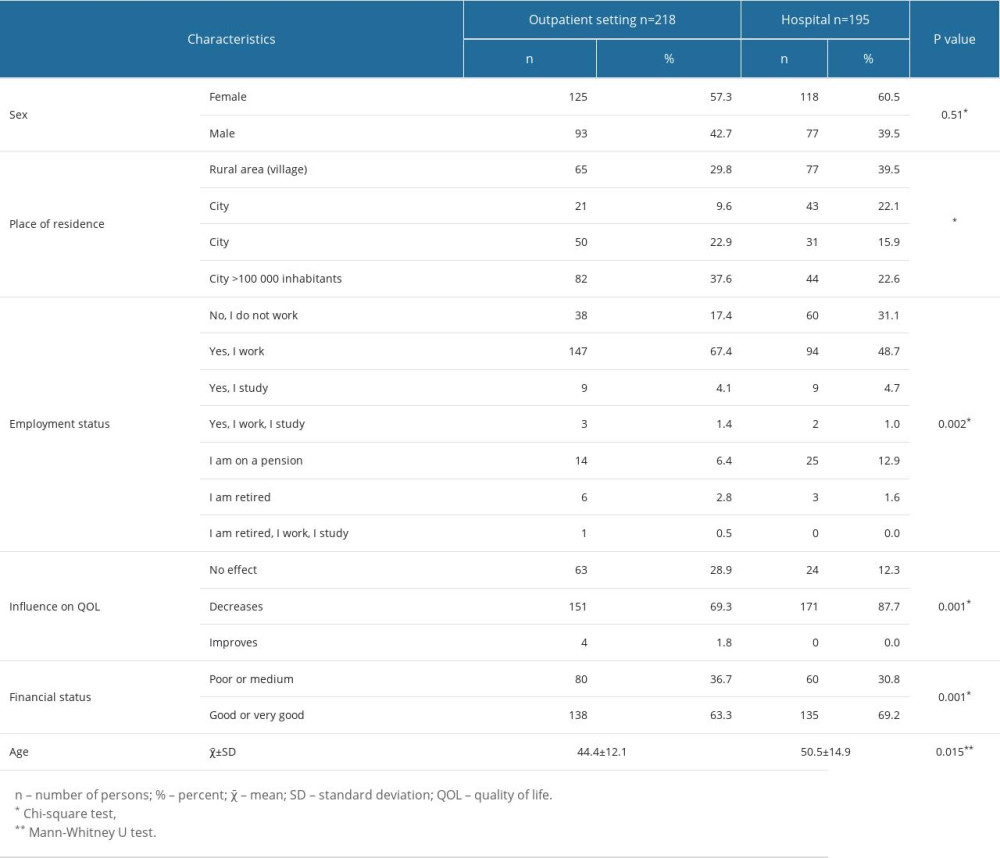

This prospective observational study was conducted between July 2019 and November 2019 on a group of 413 patients (243 women and 170 men) of the Independent Public Teaching Hospital in Lublin (Poland). A group of 195 patients was hospitalized at the Dermatology Department, while a group of 218 patients was treated on an outpatient basis at the Dermatology Clinic of the hospital. The Independent Public Teaching Hospital in Lublin is an academic, state-funded medical center where all treatment costs are covered by the public health insurance payer. The inclusion criteria were (1) patients’ age >18 years, (2) hospitalization 2 or more times or a visit to an outpatient clinic 2 or more times, and (3) an informed consent of the patient to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were (1) persons accompanying the patients, (2) discharge from the hospital on the day of data collection, (3) conscious withdrawal from the study (patient’s decision), and (4) lack of patient consent to participate in the study. Only completed questionnaires were included in the survey and analyzed. Table 1 shows detailed characteristics of the respondents.

RESEARCH TOOLS:

The commonly used SERVQUAL method was developed to assess patient service quality. It is a standardized and dedicated survey tool used worldwide to assess the quality of services [9]. In the present study, we used a modified version of the SERVQUAL questionnaire to evaluate service quality in the context of medical services. This comprehensive framework, also known as the RATER model, encompasses a set of 5 dimensions (total of 22 questions) that are instrumental in assessing and improving service quality. The questionnaire is divided into the following 5 domains with subsequent questions:

Each service quality question is analyzed under 2 evaluation criteria: “P” represents the perceptions and “E” represents the expectations of service quality. All the obtained answers had a 5-point Likert scale format: (1=I totally disagree, 5=I totally agree). The service quality index scores were obtained by calculating the difference between the ratings that the surveyed patients gave to paired perception and expectation statements, according to the following formula: service quality index=P–E. Negative service quality index scores indicate customer dissatisfaction, while positive scores indicate a high level of satisfaction [14,17]. In addition, a self-administered questionnaire was used to collect patients’ basic sociodemographic data (age, sex, employment status, place of residence, and financial status).

DATA COLLECTION:

Survey packets containing the standardized SERVQAL questionnaire and the original sociodemographic data questionnaire were successively distributed among patients of the Independent Public Teaching Hospital No. 1 in Lublin (Poland). The distributed materials accounted for the division between the patients hospitalized at the Department of Dermatology of the hospital and those treated at the hospital outpatient Dermatology Clinic. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the patients taking part were assured of complete anonymity. The distribution of the questionnaires and their collection after the patients had finished filling them in were supervised by the researchers. Subsequently, the completeness of the returned questionnaires was verified. Out of a total of 413 questionnaires completed by respondents, 388 (93.95%) complete SERVQUAL questionnaires were collected. Only 25 (6.05%) questionnaires were found to be incomplete and were ultimately not included in the study and not subjected to statistical analysis.

DATA ANALYSIS:

Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistica 13 software (StatSoft, Inc., USA) and Microsoft Excel 2007. Arithmetic means, medians, standard deviations, and the range of variability (extreme values) were calculated for the measurable variables. For the qualitative variables, the incidence rates (in percent) were calculated. All quantitative type variables examined were checked, using the Shapiro-Wilk test to determine the type of distribution. The determination of differences between expectations (E) and perceptions (P) quality scores and the group of patients treated at the clinic (C clinic, outpatient) and hospital (H, hospital, inpatient) was made using the

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS:

The study involved 413 dermatology patients (243 women and 170 men). A group of 218 patients (125 women and 93 men, mean age: 44.4±12.1) visited the outpatient clinic at the hospital, and a group of 195 patients (118 women and 77 men, mean age: 50.5±14.9) were treated at the hospital as inpatients. Table 1 shows a detailed patient characteristics, considering the treatment setting.

SEVQUAL MODEL:

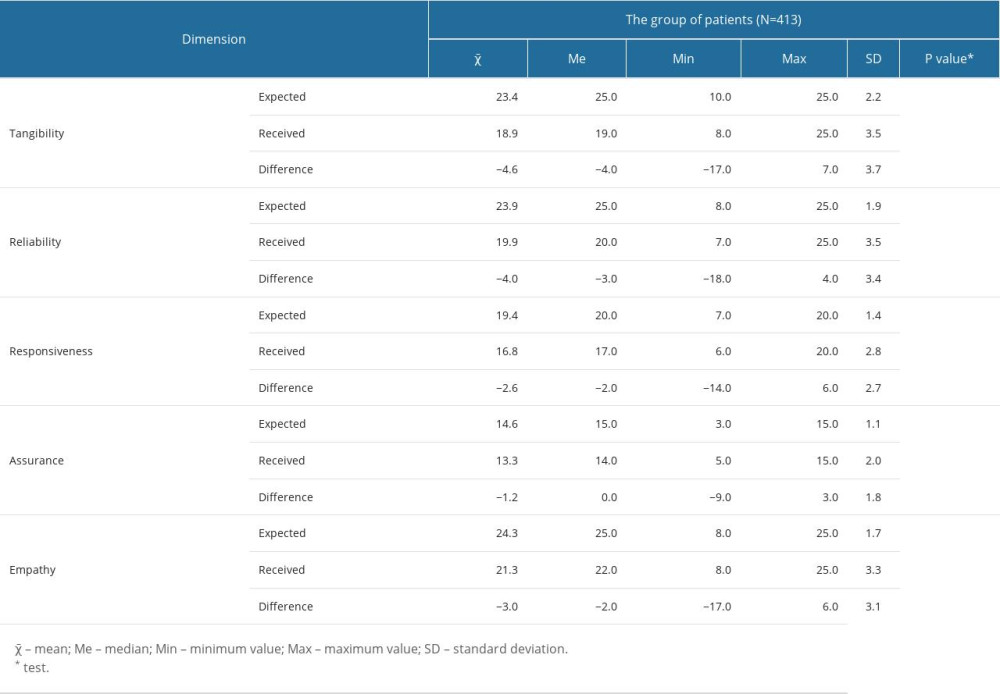

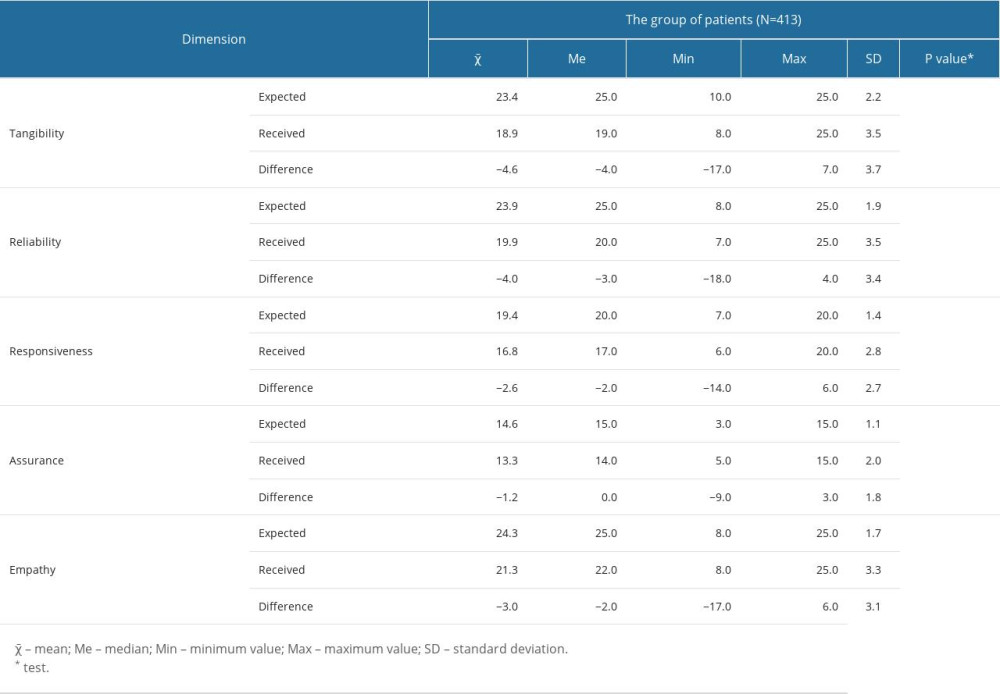

An analysis of the results for the entire group of patients studied showed that statistically significant differences between the value expected and the value received were obtained in each dimension of the SERVQUAL model. Negative difference values (service quality index) were obtained in each case, indicating higher patient expectations regarding the quality of the services received (P<0.001). The highest level of unfulfilled expectations was found in the tangibility domain, while the lowest level of unfulfilled expectations was demonstrated in the assurance domain (Table 2).

The patients’ expectations of the quality of health services provided in terms of individual dimensions in the order from highest expectations were as follows: tangibility, reliability, empathy, responsiveness, and assurance (Table 2).

ANALYSIS BY TREATMENT SETTING:

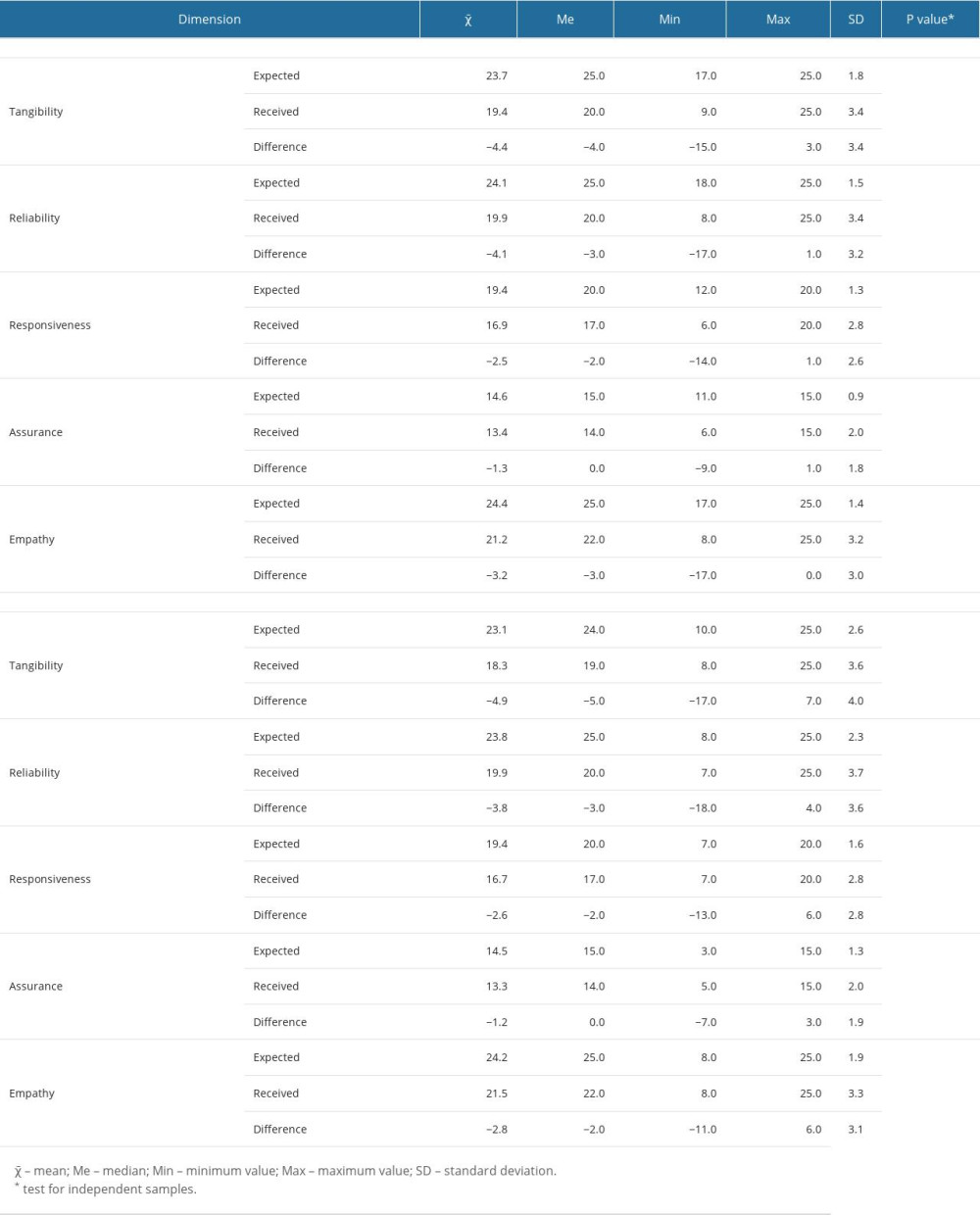

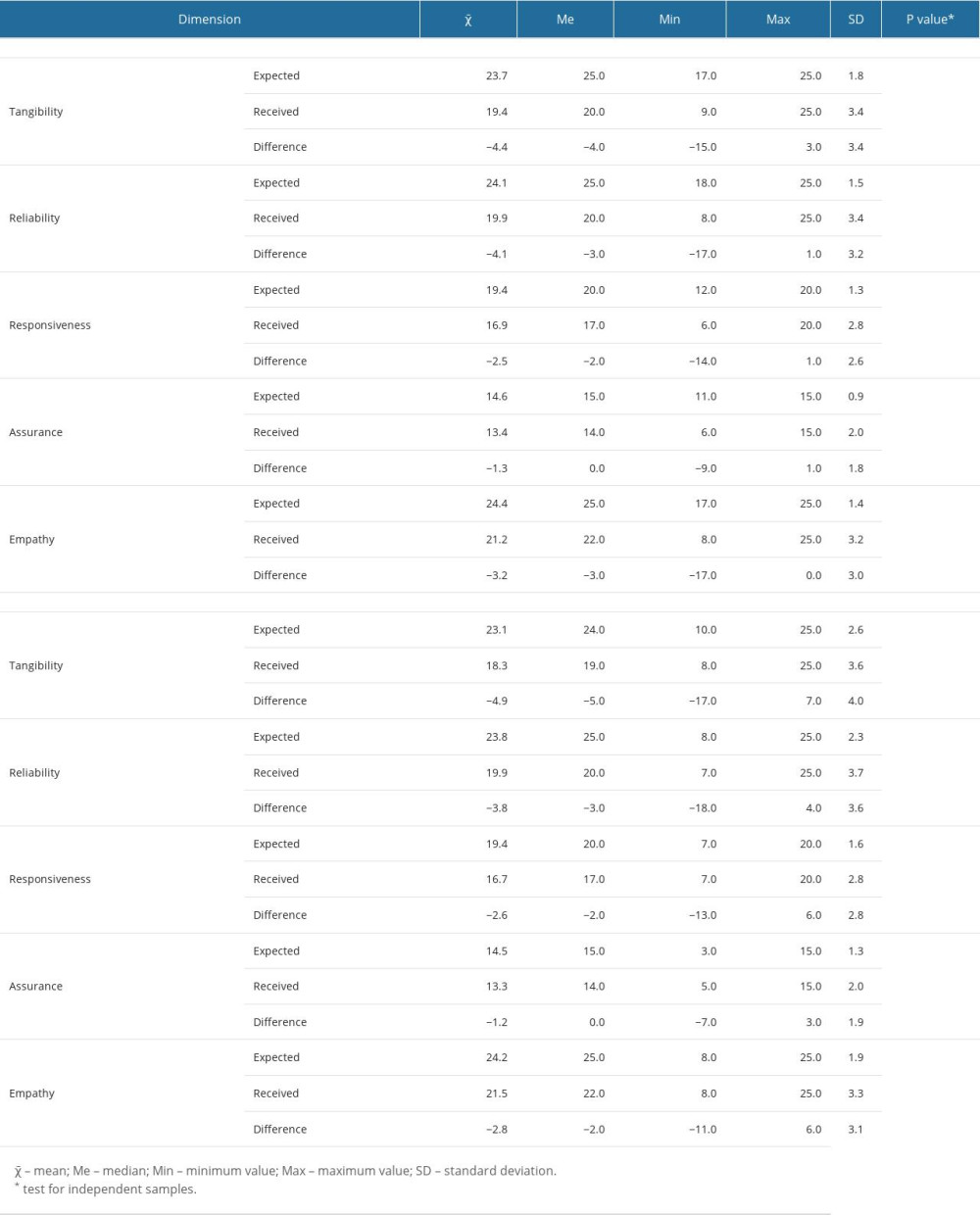

A within-group analysis for patients showed similar results. The unfulfilled expectations were related to the tangibility dimension, both in outpatient and inpatient settings. The smallest gap between what had been expected and what had been received was on the assurance dimension, at the outpatient clinic and the hospital (Table 3).

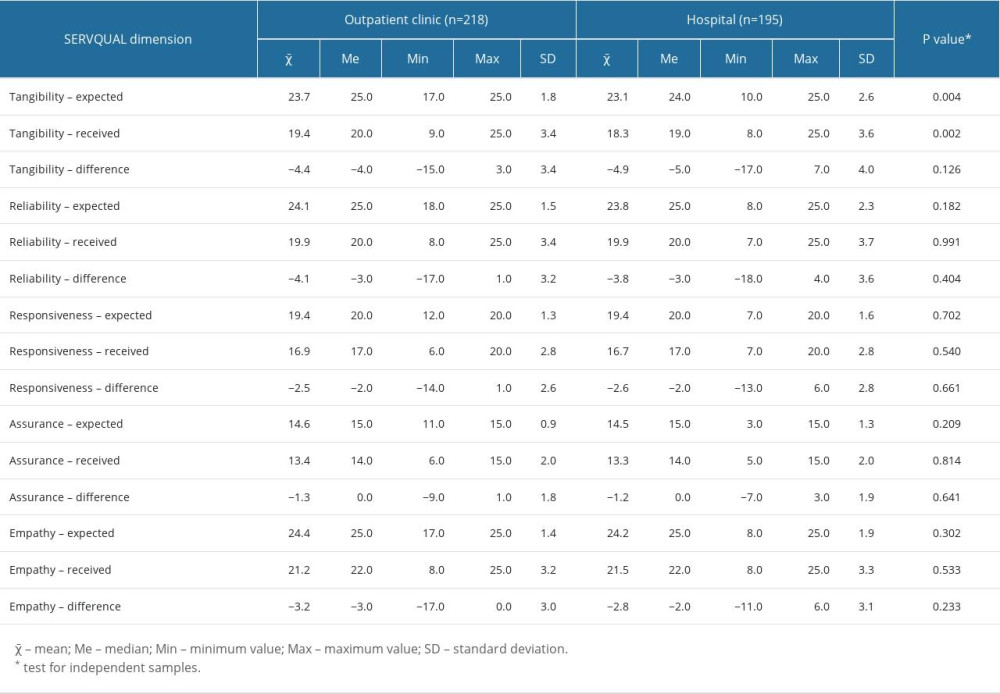

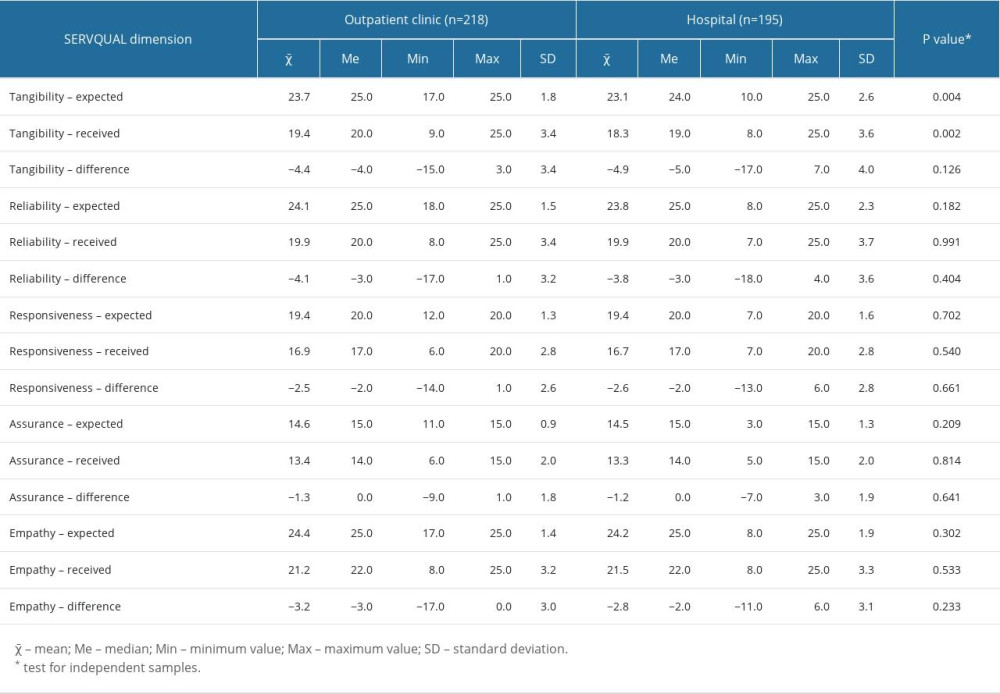

An intergroup analysis of the patients showed statistically significant differences in the tangibility dimension for expected quality: 23.7±1.8 for the outpatient clinic and 23.1±2.6 for the hospital (P=0.004), and for the quality received: 19.4±3.4 for the outpatient clinic and 18.3±3.6 for the hospital (P=0002). The other results were found to be statistically insignificant (P>0.05). The most considerable difference was observed in the level of unfulfilled expectations in the tangibility dimension of −4.4 for the outpatient clinic and −4.9 for the hospital; nevertheless, the difference was found to be statistically insignificant (P=0.126; Table 4).

ANALYSIS BY PATIENT SEX:

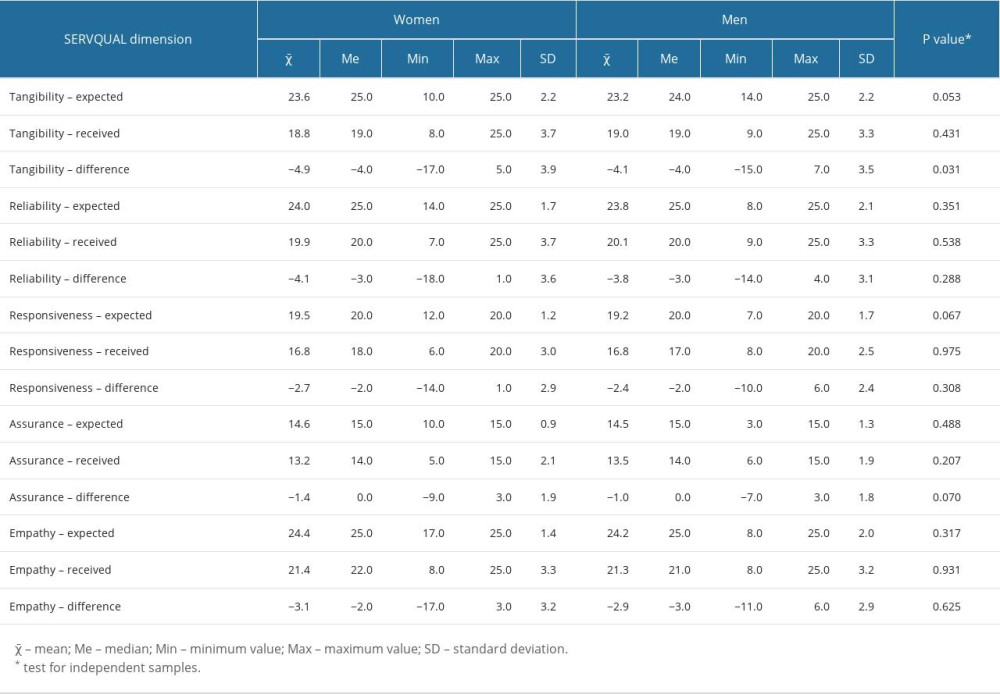

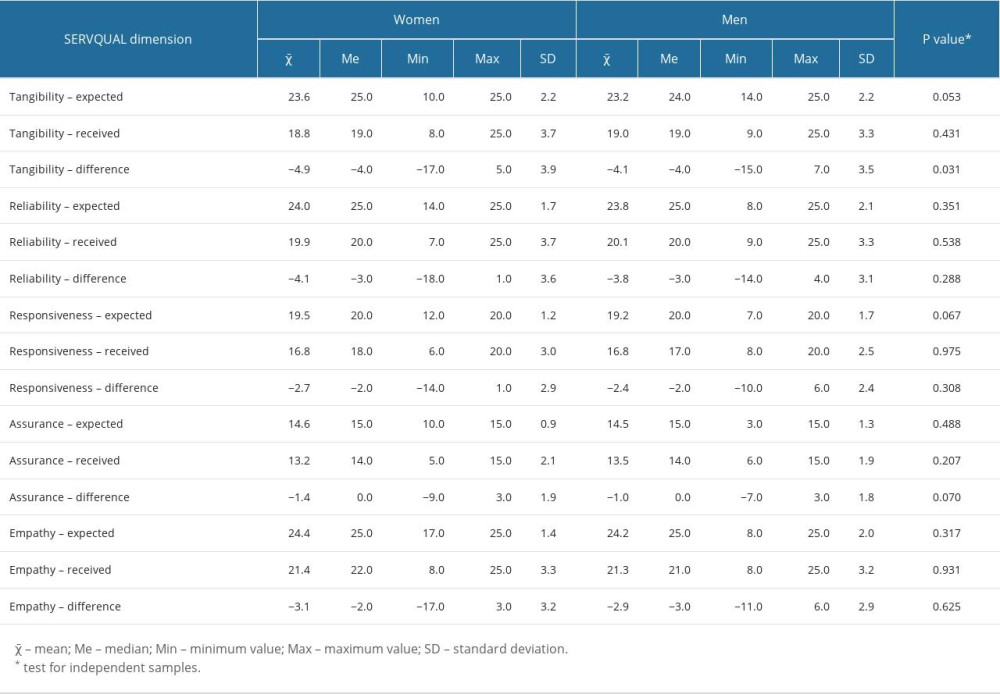

An intergroup analysis by sex for individual SERVQUAL dimensions showed a statistically significant difference between outpatients and hospital patients for the service quality rating of the tangibility domain (P=0.031). It means that women had higher expectations than did men. In contrast, service quality for the other dimensions was found to be statistically insignificant (P>0.05; Table 5).

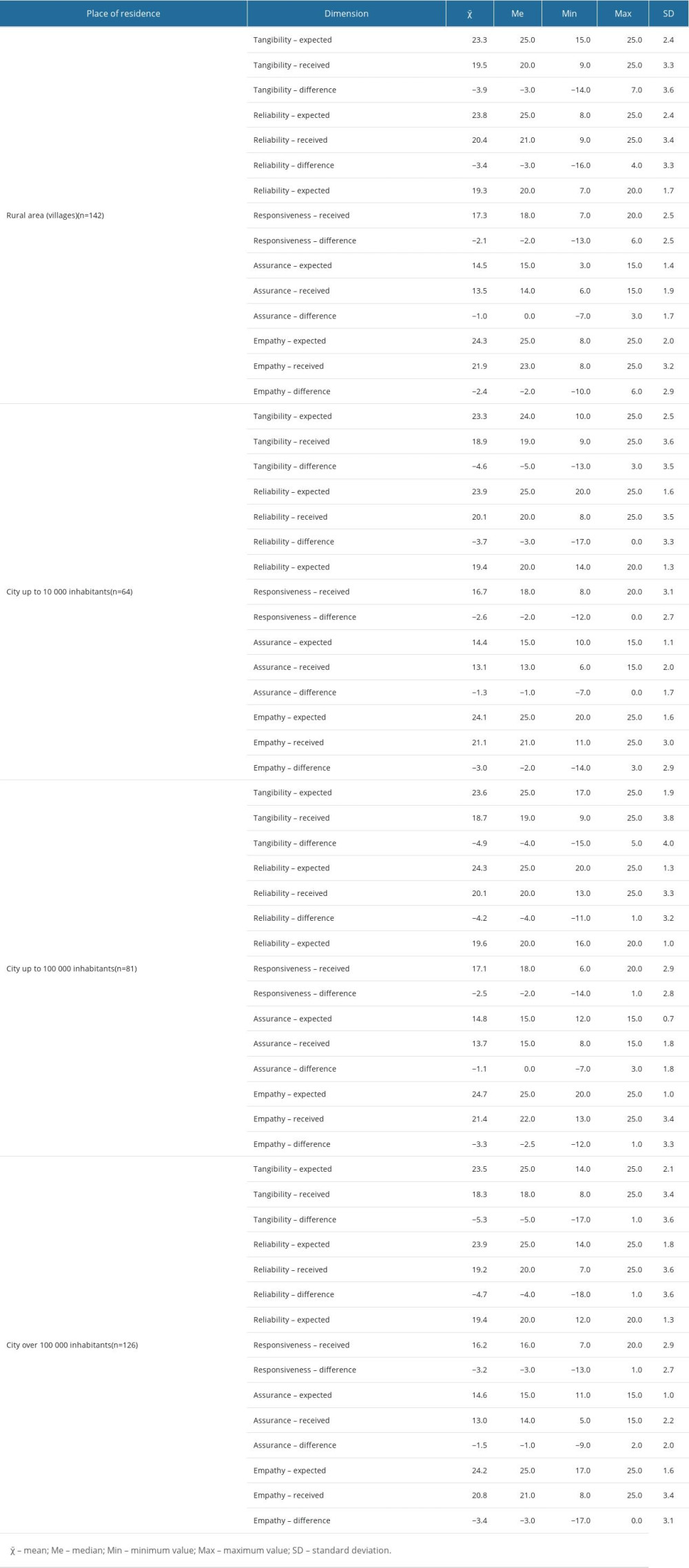

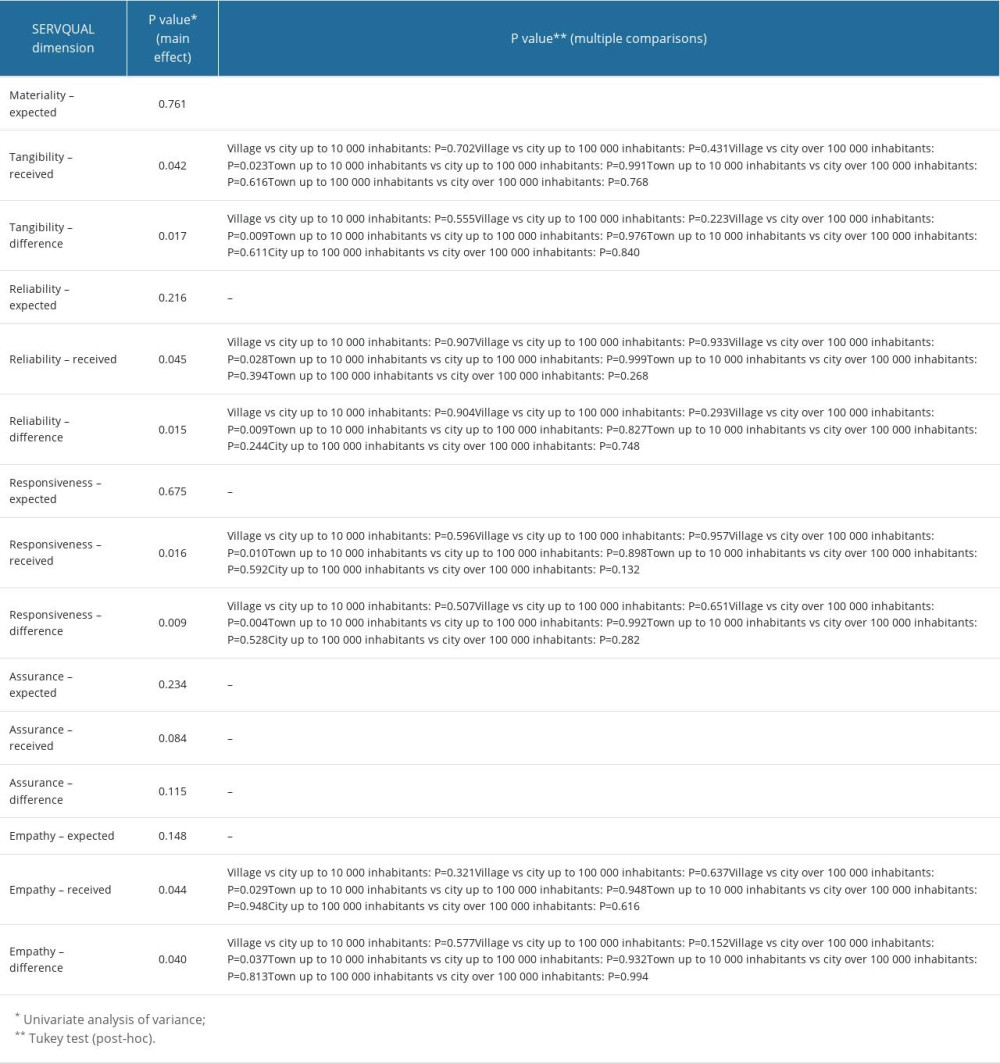

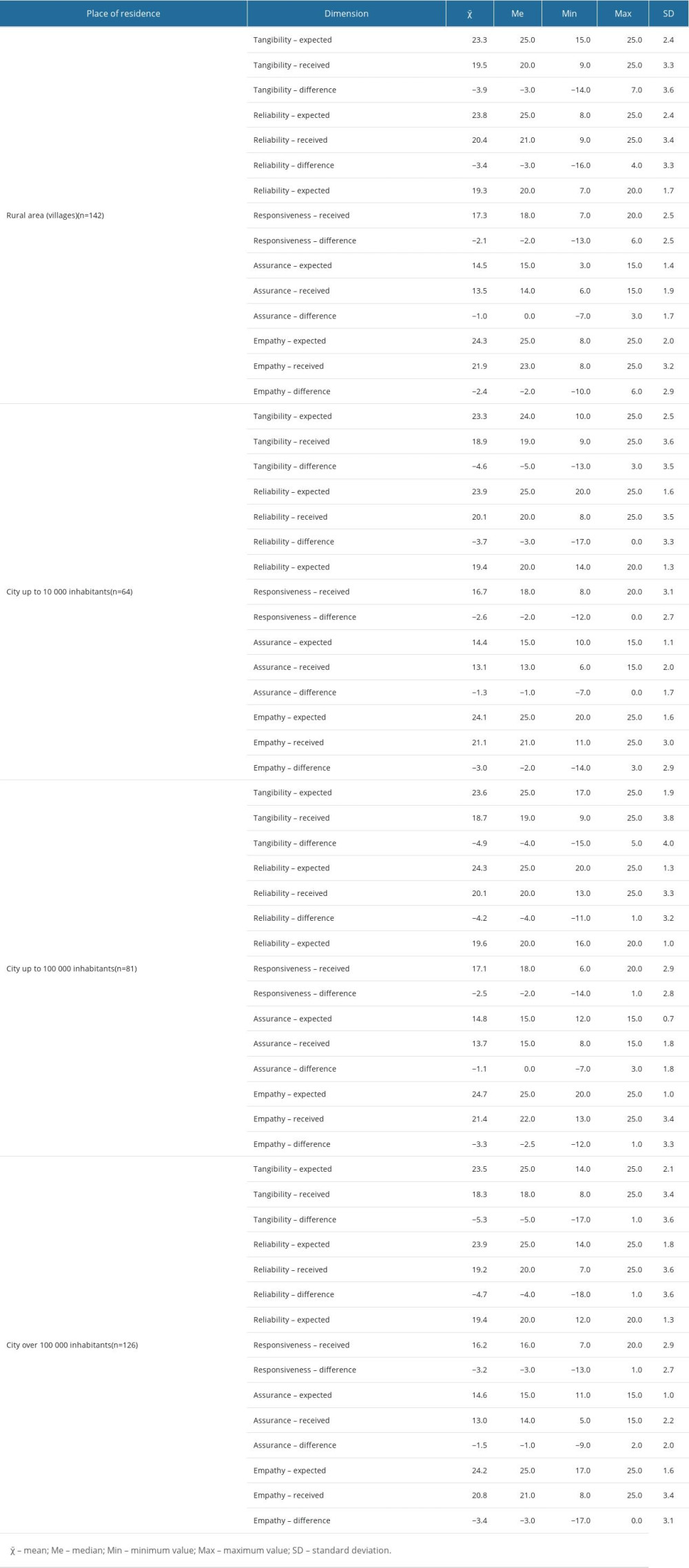

ANALYSIS BY PLACE OF RESIDENCE:

For all the surveyed participants, regardless of where they lived, the highest expectations were related to the tangibility dimension. At the same time, the lowest level of expectations was demonstrated for the assurance domain. Rural residents scored best for the reliability, responsiveness, and empathy gaps compared with those living in a city of more than 100 000 inhabitants (Table 6).

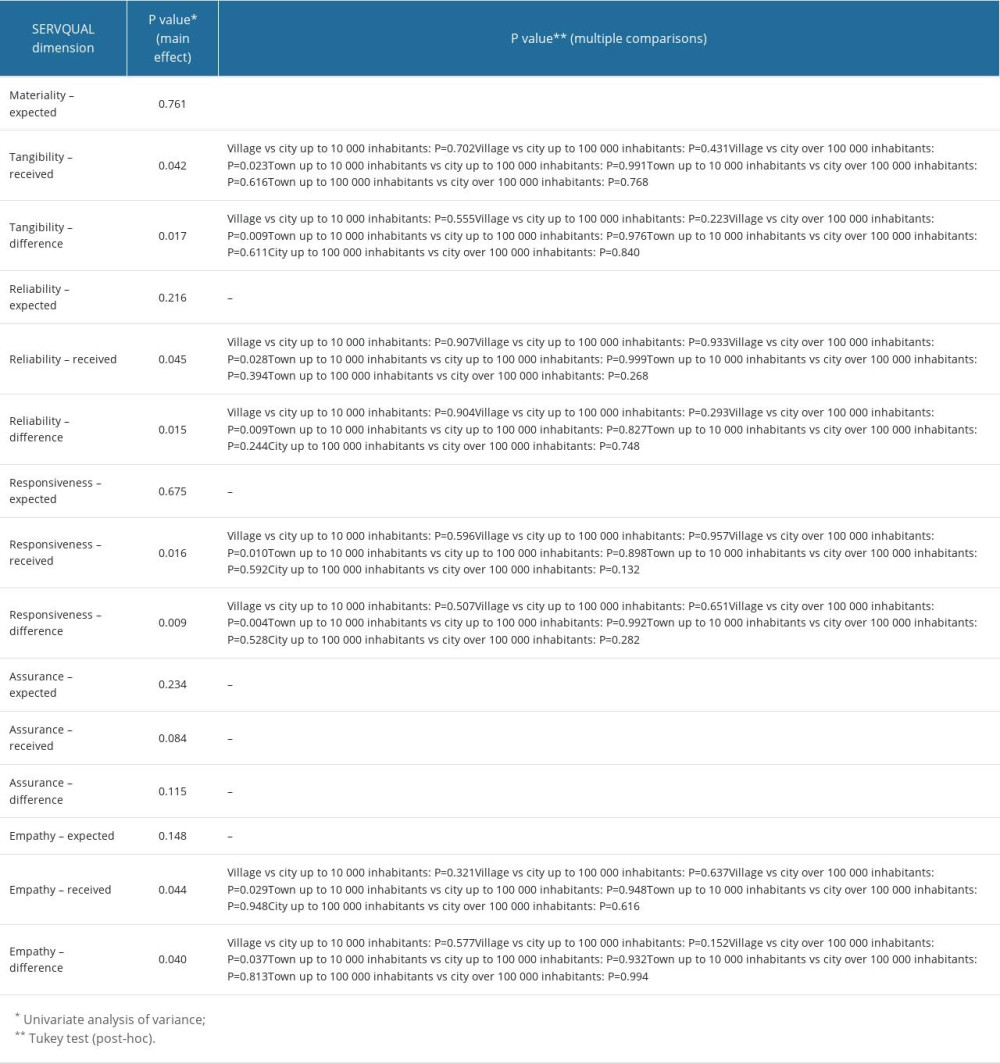

The intergroup analysis of individual dimensions in relation to the place of residence indicated statistically significant results for the quality received of the individual domains. The differences in the service quality values between the residents of rural areas and those of cities with more than 100 000 inhabitants proved statistically significant (P<0.05; Table 7).

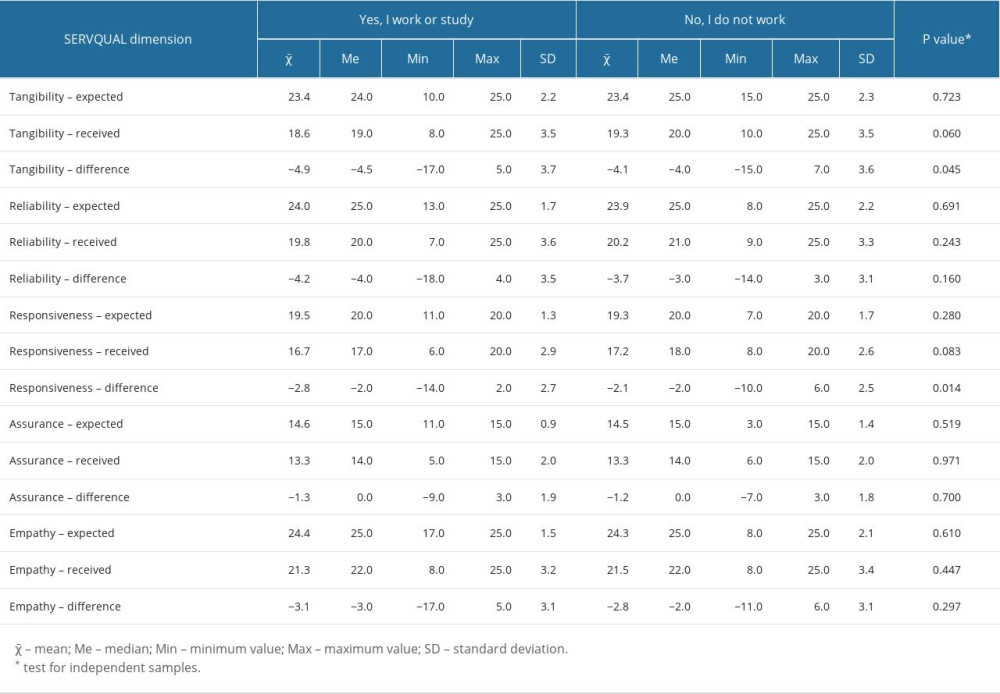

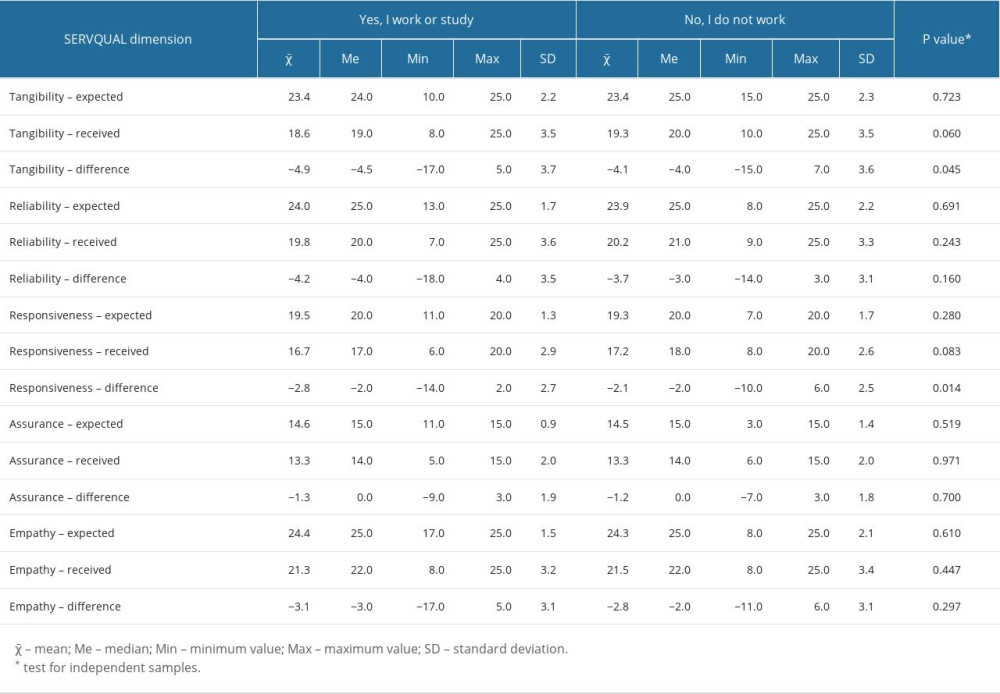

ANALYSIS BY EMPLOYMENT STATUS:

An intergroup analysis of individual dimensions in relation to employment status showed that working patients demonstrated a higher level of expectations of the services provided in the dimensions of tangibility and responsiveness than did non-working patients. In the other dimensions, the patients did not differ statistically significantly in regards to their employment status (P>0.05; Table 8).

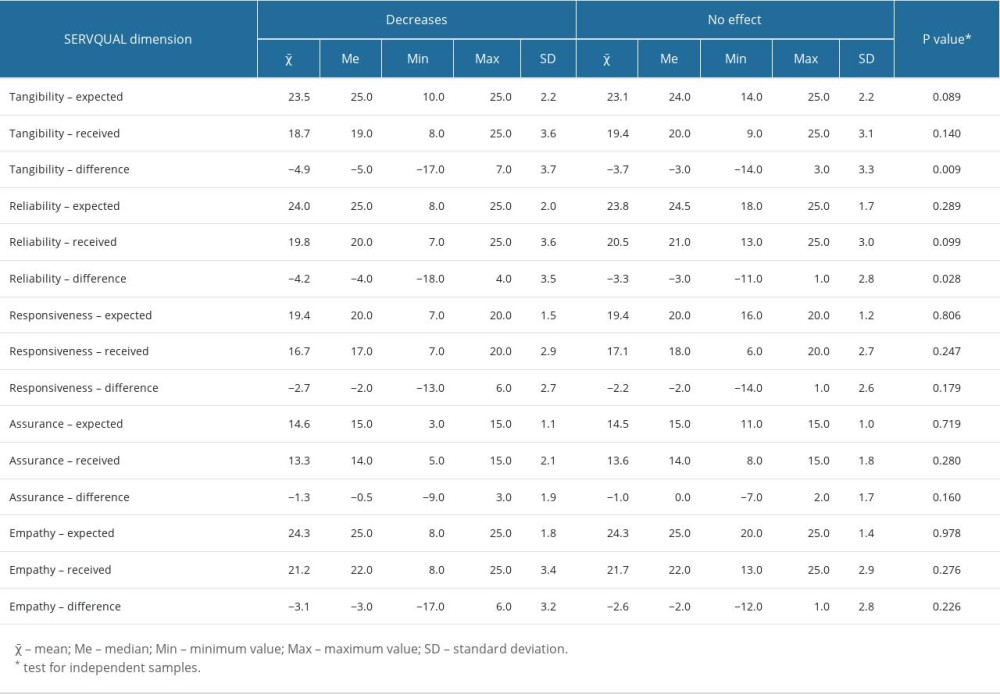

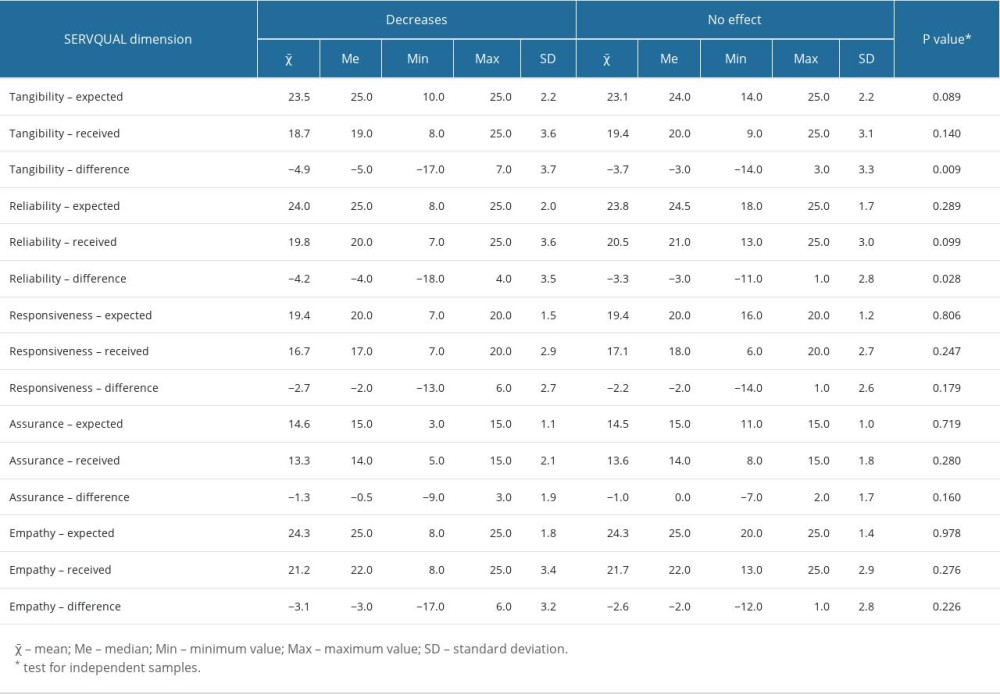

ANALYSIS BY QUALITY OF LIFE:

An intergroup analysis of individual dimensions in relation to the impact on the quality of life (QOL) showed that the patients who declared reduced in QOL had statistically significantly higher expectations of quality of services in the domains of tangibility and reliability than did patients declaring no impact on their QOL. In the other dimensions, the patients did not differ statistically significantly in regards to the impact on QOL (Table 9).

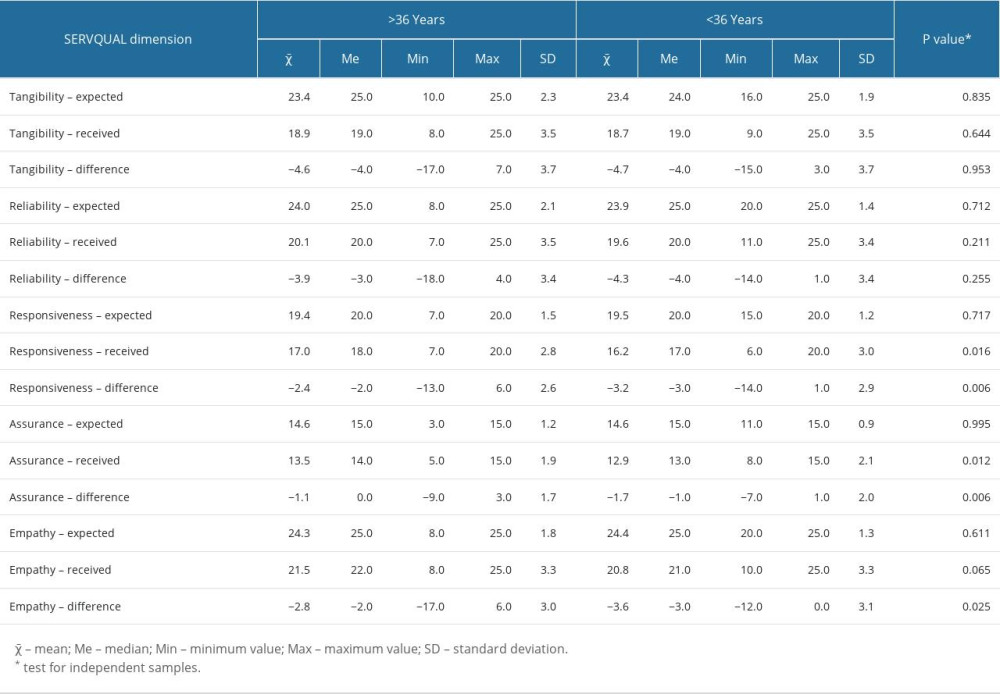

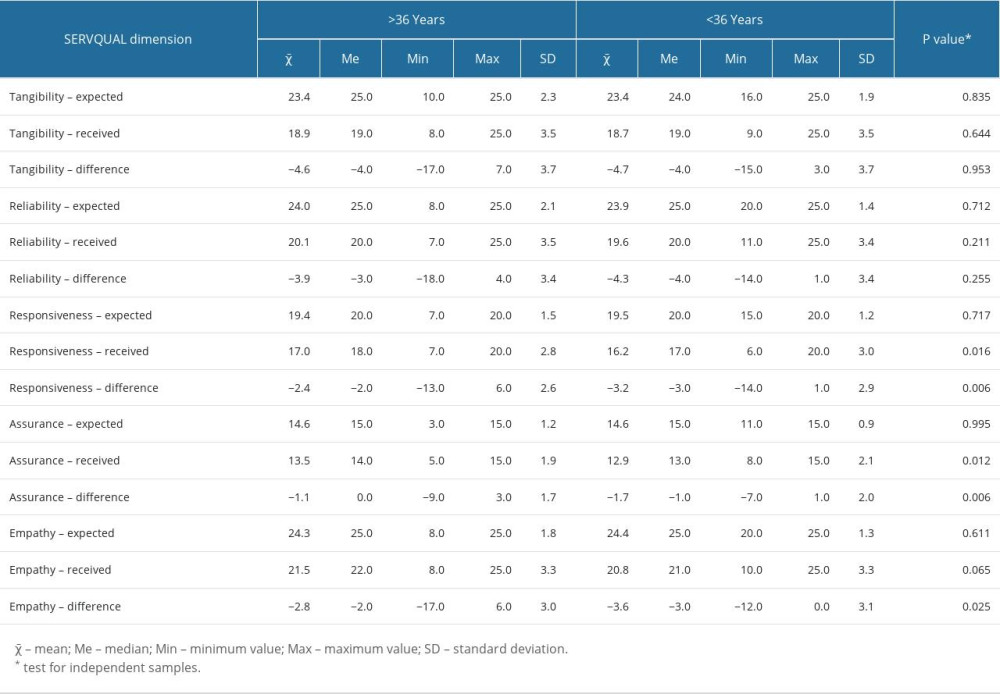

ANALYSIS BY AGE CATEGORY:

An intergroup analysis of individual dimensions in relation to the age category showed that the patients <36 years of age had demonstrated statistically significantly higher expectations of the services provided in the gaps of responsiveness, assurance, and empathy than did patients >36 years of age. Furthermore, the patients >36 years of age had statistically significantly higher scores for the quality received in the dimensions of responsiveness (P=0.016) and assurance (P=0.012). In the other dimensions, the patients did not differ statistically significantly according to age (P>0.05; Table 10).

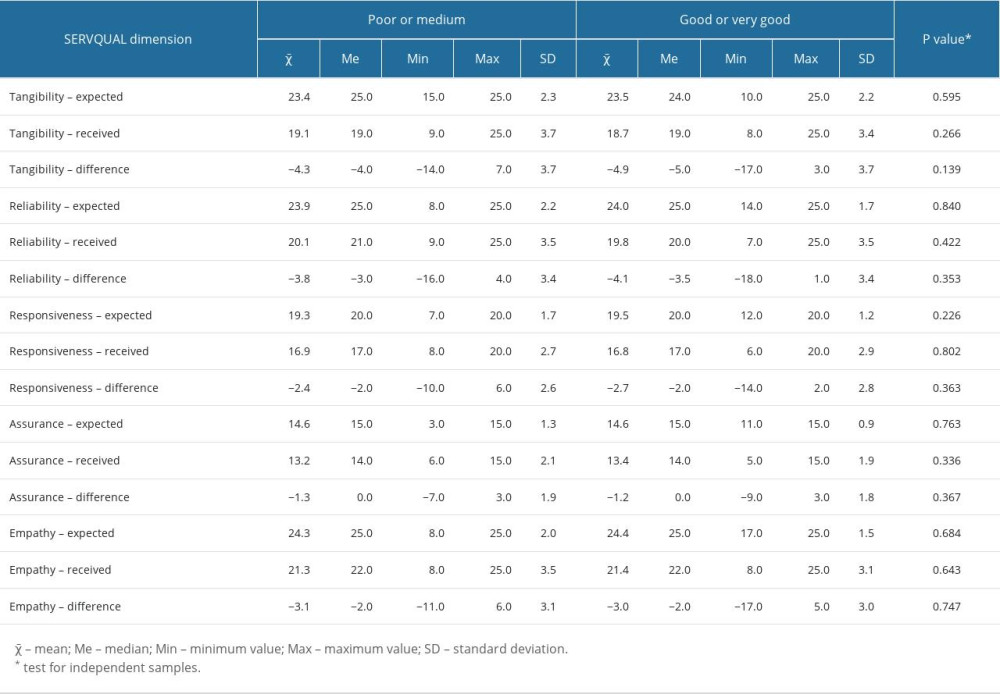

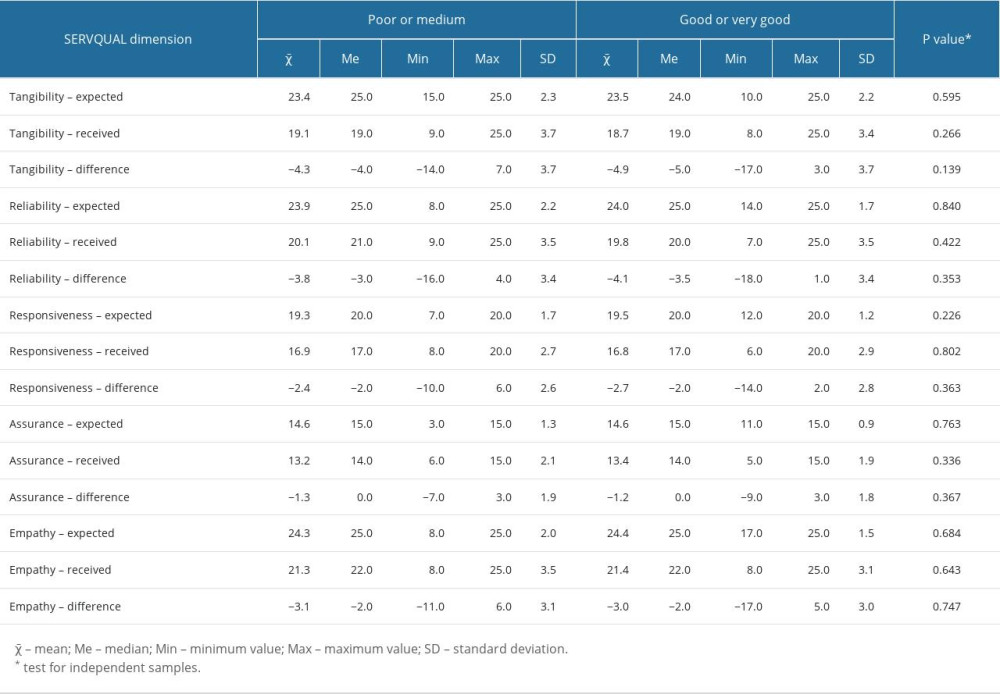

ANALYSIS BY FINANCIAL STATUS:

An intergroup analysis of individual dimensions in relation to the financial status of the patients surveyed showed no statistically significant differences between patients with a poor or medium financial status and those with a good or very good financial status (P>0.05; Table 11).

Discussion

STUDY LIMITATIONS:

Our study had some potential methodological limitations. First, we used a single subjective tool, based on the SERVQOAL model. It should be mentioned that in the assessment of medical services, the SERVQUAL model has a few disadvantages. First, it may not fully capture the complexity and technical aspects of healthcare, such as clinical outcomes and specialized treatments. Second, patient expectations in healthcare can be highly subjective and variable, making it challenging to establish a universal set of dimensions that accurately reflects their perspectives. Additionally, the model’s standardized dimensions may not adequately cater to the specific requirements and expectations of different medical specialties. It is important to note that while the SERVQUAL model has its limitations, it can still offer valuable insights into the overall service quality assessment in healthcare settings.

Our study did not focus on identifying dermatological conditions diagnosed in the patients studied. It is worth emphasizing that identifying clinical conditions can be related to the perception of healthcare quality. Therefore, further studies should consider more accurate clinical characteristics of dermatology patients in the context of assessing expectation-to-receive service quality according to the concept of the SERVQUAL model. While our study aimed to evaluate overall service quality in a dermatology clinic and hospital, it is important to consider that patient expectations can differ based on the severity or nature of their specific conditions. Future studies could consider conducting separate analyses or sub-analyses for specific dermatological conditions to provide more targeted insights into patient expectations and service quality perceptions within those contexts.

Conclusions

The field of dermatology plays a crucial role in patient-centered medicine, and the availability of quick diagnostics, effective treatment, and high-quality services provided by qualified dermatologists are central to ensuring patient satisfaction. Chronic skin diseases require long-term care and regular follow-up visits. Patient satisfaction with the services they receive is gaining attention, and factors such as doctor’s care, interest in the medical problem, and attention to the patient’s needs are important determinants of satisfaction. The results of this study provide valuable insights into the factors influencing patient satisfaction in dermatology and contribute to the ongoing efforts to improve the quality of care and enhance patient experiences and outcomes.

Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants with a division into the clinic (outpatients) and hospital (inpatients). Table 2. SERVQUAL results for the entire group of the patients surveyed.

Table 2. SERVQUAL results for the entire group of the patients surveyed. Table 3. Results of the within-group SERVQAL analysis for outpatient clinic and hospital patients.

Table 3. Results of the within-group SERVQAL analysis for outpatient clinic and hospital patients. Table 4. Results of the intergroup SERVQAL analysis for the outpatient clinic and hospital patients.

Table 4. Results of the intergroup SERVQAL analysis for the outpatient clinic and hospital patients. Table 5. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the sex of the patients surveyed.

Table 5. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the sex of the patients surveyed. Table 6. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by place of residence of the patients surveyed.

Table 6. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by place of residence of the patients surveyed. Table 7. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by place of residence of the patients surveyed.

Table 7. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by place of residence of the patients surveyed. Table 8. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by employment status of the patients surveyed.

Table 8. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by employment status of the patients surveyed. Table 9. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the quality of life of the patients surveyed.

Table 9. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the quality of life of the patients surveyed. Table 10. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the age category of the patients surveyed.

Table 10. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the age category of the patients surveyed. Table 11. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the financial status of the surveyed individuals.

Table 11. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the financial status of the surveyed individuals.

References

1. Lohr KNInstitute of Medicine (US) Committee to Design a Strategy for Quality Review and Assurance in Medicare: Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance: VOLUME II Sources and Methods, 1990; 5, Washington (DC), National Academies Press (US) Defining Quality of Care. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235476

2. Shaw C, Groene O, Mora N, Sunol R, Accreditation and ISO certification: Do they explain differences in quality management in European hospitals?: Int J Qual Health Care, 2010; 22(6); 445-51

3. World Health Organization: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Conceptual and Strategic Approach to Family Practice: Towards Universal Health Coverage through Family Practice in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 2014, World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250529

4. Christoglou K, Vassiliadis C, Sigalas I, Using SERVQUAL and Kano research techniques in a patient service quality survey: World Hosp Health Serv, 2006; 42(2); 21-26

5. Ćwiklicki M, Quality service measurement for organisations supporting social economy: Empirical findings: Soc Econ, 2010(1); 35-45

6. Durrani H, Healthcare and healthcare systems: inspiring progress and future prospects: Mhealth, 2016; 2; 3

7. De Man S, Gemmel P, Vlerick P, Patients’ and personnel’s perceptions of service quality and patient satisfaction in nuclear medicine: Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2002; 29(9); 1109-17

8. Rahim AIA, Ibrahim MI, Musa KI, Patient satisfaction and hospital quality of care evaluation in Malaysia using SERVQUAL and Facebook: Healthcare (Basel), 2021; 9(10); 1369

9. Parasuraman A, Zeithaml V, Berry L, SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality: Journal of Retailing, 1988; 64(1); 12-40

10. De Man S, Vlerick P, Gemmel P, Impact of waiting on the perception of service quality in nuclear medicine: Nucl Med Commun, 2005; 26(6); 541-47

11. Williams JR, Gavin LE, Carter MW, Glass E, Client and provider perspectives on quality of care: A systematic review: Am J Prev Med, 2015; 49(2 Suppl 1); S93-106

12. Dopeykar N, Bahadori M, Mehdizadeh P, Assessing the quality of dental services using SERVQUAL model: Dent Res J (Isfahan), 2018; 15(6); 430-36

13. Lu SJ, Kao HO, Chang BL, Identification of quality gaps in healthcare services using the SERVQUAL instrument and importance-performance analysis in medical intensive care: A prospective study at a medical center in Taiwan: BMC Health Serv Res, 2020; 20; 908

14. Jonkisz A, Karniej P, Krasowska D, SERVQUAL method as an “old new” tool for improving the quality of medical services: A literature review: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(20); 10758

15. Ko CH, Chou CM, Apply the SERVQUAL instrument to measure service quality for the adaptation of ICT technologies: A case study of nursing homes in Taiwan: Healthcare (Basel), 2020; 8(2); E108

16. Javed SA, Liu S, Mahmoudi A, Nawaz M, Patients’ satisfaction and public and private sectors’ health care service quality in Pakistan: Application of grey decision analysis approaches: Int J Health Plann Manage, 2019; 34(1); e168-e82

17. Manulik S, Rosińczuk J, Karniej P, Evaluation of health care service quality in Poland with the use of SERVQUAL method at the specialist ambulatory health care center: Patient Prefer Adherence, 2016; 10; 1435-42

18. Taner T, Antony J, Comparing public and private hospital care service quality in Turkey: Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv, 2006; 19(2-3); i-x

19. Busse R, Panteli D, Quentin W, An introduction to healthcare quality: Defining and explaining its role in health systems: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549277/

20. Ghahramanian A, Rezaei T, Abdullahzadeh F, Quality of healthcare services and its relationship with patient safety culture and nurse-physician professional communication: Health Promot Perspect, 2017; 7(3); 168-74

21. Gavurova B, Dvorsky J, Popesko B, Patient satisfaction determinants of inpatient healthcare: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(21); 11337

22. van Hoof SJM, Quanjel TCC, Kroese MEAL, Substitution of outpatient hospital care with specialist care in the primary care setting: A systematic review on quality of care, health and costs: PLoS One, 2019; 14(8); e0219957

23. Mentz RJ, Hernandez AF, Berdan LG, Good clinical practice guidance and pragmatic clinical trials: Balancing the best of both worlds: Circulation, 2016; 133(9); 872-80

24. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies: J Clin Epidemiol, 2008; 61(4); 344-49

25. Bezalel SA, Otley CC, Invention in dermatology: A review: J Drugs Dermatol, 2019; 18(9); 904-8

26. Chapman R, The importance of patient-centered care: Chest, 2021; 159(1); 439-40

27. Iqbal U, Khan HAA, Li YCJ, The global challenges for quality improvement and patient safety: Int J Qual Health Care, 2021; 33(1); mzaa046

28. Singh S, Ehsani-Chimeh N, Kornmehl H, Armstrong AW, Quality of life among dermatology patients: A systematic review of investigations using qualitative methods: G Ital Dermatol Venereol, 2019; 154(1); 72-78

29. Nakamura M, Briones NF, Thy Do T, Dermatologist demographics and patient satisfaction: A single-center survey study: Int J Womens Dermatol, 2020; 6(4); 290-93

30. Brenaut E, De Salins CA, Misery L, Roguedas-Contios AM, Patient satisfaction in dermatology: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2017; 31(7); e343

31. Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Amici JM, Roy-Geffroy B, Dermatosurgery: Total quality management in a dermatology department: Dermatology, 2012; 225(3); 204-9

32. De Salins CA, Brenaut E, Misery L, Roguedas-Contios AM, Factors influencing patient satisfaction: Assessment in outpatients in dermatology department: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2016; 30(10); 1823-28

33. Bos JD, Schram ME, Mekkes JR, Dermatologists are essential for quality of care in the general practice of medicine: Actas Dermosifiliogr, 2009; 100(Suppl 1); 101-5

34. Uhlenhake E, Feldman SR, Dermatological patient safety: Problems and solutions: J Dermatolog Treat, 2010; 21(2); 86-92

35. Renzi C, Abeni D, Picardi A, Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients: Br J Dermatol, 2001; 145(4); 617-23

36. Marzo RR, Bhattacharya S, Ujang NB, The impact of service quality provided by health-care centers and physicians on patient satisfaction: J Educ Health Promot, 2021; 10; 160

37. Sutton AV, Ellis CN, Spragg S, Improving patient satisfaction in dermatology: A prospective study of an urban dermatology clinic: Cutis, 2017; 99(4); 273-78

38. Ali ST, Feldman SR, Patient satisfaction in dermatology: A qualitative assessment: Dermatol Online J, 2014; 20(2); doj_21534

39. Trager MH, Queen D, Fan W, Samie FH, Patient satisfaction of general dermatologists: A quantitative and qualitative analysis of 38,008 online reviews by gender and years of experience: JID Innov, 2021; 2(2); 100089

40. Godillot C, Jendoubi F, Konstantinou MP, How to assess patient satisfaction regarding physician interaction: A systematic review: Dermatol Ther, 2021; 34(2); e14702

41. Poot F, Doctor-patient relations in dermatology: Obligations and rights for a mutual satisfaction: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2009; 23(11); 1233-39

42. Sorenson E, Malakouti M, Brown G, Koo J, Enhancing patient satisfaction in dermatology: Am J Clin Dermatol, 2015; 16(1); 1-4

Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants with a division into the clinic (outpatients) and hospital (inpatients).

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants with a division into the clinic (outpatients) and hospital (inpatients). Table 2. SERVQUAL results for the entire group of the patients surveyed.

Table 2. SERVQUAL results for the entire group of the patients surveyed. Table 3. Results of the within-group SERVQAL analysis for outpatient clinic and hospital patients.

Table 3. Results of the within-group SERVQAL analysis for outpatient clinic and hospital patients. Table 4. Results of the intergroup SERVQAL analysis for the outpatient clinic and hospital patients.

Table 4. Results of the intergroup SERVQAL analysis for the outpatient clinic and hospital patients. Table 5. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the sex of the patients surveyed.

Table 5. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the sex of the patients surveyed. Table 6. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by place of residence of the patients surveyed.

Table 6. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by place of residence of the patients surveyed. Table 7. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by place of residence of the patients surveyed.

Table 7. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by place of residence of the patients surveyed. Table 8. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by employment status of the patients surveyed.

Table 8. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by employment status of the patients surveyed. Table 9. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the quality of life of the patients surveyed.

Table 9. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the quality of life of the patients surveyed. Table 10. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the age category of the patients surveyed.

Table 10. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the age category of the patients surveyed. Table 11. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the financial status of the surveyed individuals.

Table 11. Results of the intergroup analysis of particular dimensions in the SERVQUAL model by the financial status of the surveyed individuals. In Press

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Metabolomic Alterations in Methotrexate Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe PsoriasisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943360

14 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Renal Dysfunction Increases Risk of Adverse Cardiovascular Events in 5-Year Follow-Up Study of Intermediate...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943956

15 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Impact of One-Lung Ventilation on Oxygenation and Ventilation Time in Thoracoscopic Heart Surgery: A Compar...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943089

14 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Differential DHA and EPA Levels in Women with Preterm and Term Births: A Tertiary Hospital Study in IndonesiaMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943895

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952