13 November 2023: Clinical Research

Enhanced Patient Comfort and Satisfaction with Early Oral Feeding after Thoracoscopic Lung Cancer Resection

Yinghong Wu1ABCDEFG, Huiling Liu1DF, Minghao Zhong1BCDEF, Xiyi Chen1BDF, Zhiqiong Ba1BF, Guibin Qiao1DE, Jiejie Feng1G, Xiuqun Zeng2ADE*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.941577

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e941577

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The study aimed to compare the patient-reported outcomes in patients who underwent early vs conventional feeding after thoracoscopic lung cancer resection.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The study enrolled 211 patients who underwent thoracoscopic lung cancer resection at a tertiary hospital between July 2021 and July 2022. Patients were randomly assigned to the conventional group or the early feeding group. There were 106 patients in the early feeding group and 105 patients in the conventional group. The conventional group received water 4 h after extubation and liquid/semi-liquid food 6 h after extubation. In contrast, the early feeding group received water 1 h after extubation and liquid/semi-liquid food 2 h after extubation. The primary outcomes were the degree of hunger, thirst, nausea, and vomiting. The secondary outcomes were postoperative complications, duration of hospital stay, and chest tube drainage.

RESULTS: No differences were found between the 2 groups in the degrees of postoperative nausea, vomiting, or pain after extubation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 h. Postoperative complications, duration of chest tube drainage, and duration of hospital stay were also similar (P=0.567, P=0.783, P=0.696). However, the hunger and thirst scores after extubation for 2 h and 4 h decreased and were lower in the early feeding group (both P<0.001). No patients developed choking, postoperative aspiration, gastrointestinal obstruction, or other complications.

CONCLUSIONS: Early oral feeding after thoracoscopic lung cancer resection is safe and can increase patient comfort postoperatively.

Keywords: Enteral Nutrition, Lung Neoplasms, Patient Reported Outcome Measures, Thoracic Surgery

Background

Lung cancer has topped the ranking of cancer-induced morbidity and mortality worldwide, becoming the most common cancer in China according to a report published by an international cancer research organization [1]. At present, thoracoscopic surgery is always considered the main treatment of lung cancer [2], and along with the increase in lung cancer morbidity, the popularity of video-assisted thoracic surgery has also been growing rapidly [3,4]. Clinically, since lung surgery involves the respiratory system, discomfort such as throat pain, throat edema, hoarseness, and cough caused by endotracheal intubation during the operation may increase the incidence of choking and aspiration during postoperative eating, thus leading to lung infection [5]. The traditional view is that the first postoperative meal should be after the patient’s first flatus [6] because early postoperative eating will raise the incidence of nausea and vomiting after surgery.

Compelling evidence indicates that feeding through the digestive system soon after surgery is safe and leads to positive outcomes [7,8]. In recent decades, fast-track rehabilitation has become more and more popular in clinical practice [9,10]. Several studies have shown that early postoperative eating is safe and helps alleviate postoperative thirst and hunger, accelerate recovery of gastrointestinal function, and reduce postoperative discomfort [11,12]. The European adult and child perioperative fasting guidelines state that if the patient’s vital signs are normal after surgery, the postoperative drinking time should be flexibly adjusted according to the patient’s needs [13]. Patients have been fasting for at least 8 h before the operation, so they are suffering from hunger, thirst and other discomfort. Several hours earlier seems minimal for other persons, but for patients undergoing fasting, every minute counts. Shortening the time for observation is important for both the doctors and patients, and early feeding can shorten the hospital stay [7]. However, research reports show that only 2% of doctors accept the concept of early eating, and the implementation rate of early postoperative diet is still low [14]. In fact, early enteral nutrition is recommended not only for postoperative patients, but also for most critically ill patients, with certain precautions [15,16]. Clinical research on early resumption of eating has mainly focused on patients after gastrointestinal surgery, and there have been few studies on early eating after non-gastrointestinal surgery. In addition, there are few reports of patient-reported outcomes in these studies. Patient-reported outcomes are data that are not “processed” by the medical staff and directly come from the patient’s report on their health status, which truly reflects the actual situation of the patient [17]. Implementing an early diet program is crucial for lung cancer patients to resume eating and drinking soon after surgery. Therefore, this study aimed to compare patient-reported outcomes in 211 patients who underwent early feeding at 1 h and 4 h after thoracoscopic lung cancer resection at a tertiary hospital in Guangzhou, China.

Material and Methods

PARTICIPANTS:

Participant recruitment was carried out before the surgery. The criteria for inclusion were: patients undergoing their first thoracoscopic lung cancer resection under general anesthesia; age ≤70 years old; no mental illness or communication disorder; normal swallowing function and gastrointestinal tract before the operation; and voluntarily participated in the trial and provided signed informed consent. Patients were excluded if the operation was changed to thoracotomy due to the patient’s condition; operation time ≥4 h; patients undergoing lung sleeve resection or total pneumonectomy; transferred to intensive care unit after operation; and intraoperative fluid infusion ≥1500 ml. All patients used an analgesia pump after the operation.

In consideration of the human resources of the department and the actual situation of the clinic, to ensure data accuracy, only the patients who were sent to the operating room before 12: 00 (noon) were included in this trial. To ensure the safety of the trial, the patients with long operative time, high operation risk, or older age are excluded from the trial. The number of patients required to be recruited was estimated using Power and Sample Size Calculation 11 software. We set the test standard α as 0.05 and β was set as 0.1. The total sample capacity of this trial was 214 patients, 107 in each group. All surgical procedures were conducted by the same surgical team, and all patients received standard anesthesia.

INTERVENTION AND DATA COLLECTION:

The patients were randomly assigned to either the early feeding group or the conventional group. The early feeding group consisted of patients who had their tracheal intubation removed for 1 h, had normal vital signs, and expressed a desire to eat. Before being given drinking water, their degree of wakefulness was assessed by Steward recovery score [18]; water swallowing was only allowed when the test score was over 6 [19]. If the swallowing function assessment result was grade I to II, the patient was instructed to drink less than 100 ml of warm water and was then observed for 1 h. If there was no gastrointestinal discomfort, a small amount of liquid or semi-liquid diet could be given if the patient wanted it.

The conventional group included patients who received routine postoperative care and had their first drink 4 h after extubation. After their wakefulness and swallowing ability were evaluated using the Steward recovery score and the water swallowing test, patients were given less than 100 ml of warm water to drink, and they could have liquid or semi-liquid nutrients 6 h after extubation.

The researcher in charge distributed questionnaires to evaluate patient symptoms and discomfort, including hunger, thirst, nausea, vomiting, and pain. Patients were reminded to complete the questionnaires at 1, 2, 4, and 8 h after their tracheal intubation was removed. Basic verbal instructions on how to fill out the questionnaires were provided to the patients.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY OUTCOMES:

The primary outcomes included the degree of hunger and thirst and the severity of nausea, vomiting, and pain. The severity of nausea and vomiting was graded according to a Word Health Organization scoring system [20] with the following criteria: Grade 1 is no nausea and vomiting; Grade 2 is nausea and 1 episode of vomiting; Grade 3 is 2–5 episodes of transient vomiting; and Grade 3 is 6–10 episodes of vomiting requiring treatment [20]. The severity of pain was evaluated using the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory [21], which is a subjective measure of pain intensity in adults. It is a segmented numeric version of the visual analog scale in which a respondent selects a whole number from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (worst imaginable pain). Hunger and thirst were evaluated and graded as follows: Grade 0 indicated no hunger or thirst; Grade 1 indicated slight hunger or thirst; Grade 2 indicated moderate hunger or thirst that was bearable; and Grade 3 indicated intolerable hunger or thirst, or the presence of dehydration or hypoglycemia. All scores were collected through paper-based patient-reported outcomes. The secondary outcomes, assessed by the physician in charge, included postoperative complications, the duration of chest tube drainage, and the number of days spent in the hospital.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

SPSS 25.0 was used for data entry and analysis. Measurement data are expressed as mean±standard deviation, and enumeration data are expressed as frequency and percentage. The

Results

PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS:

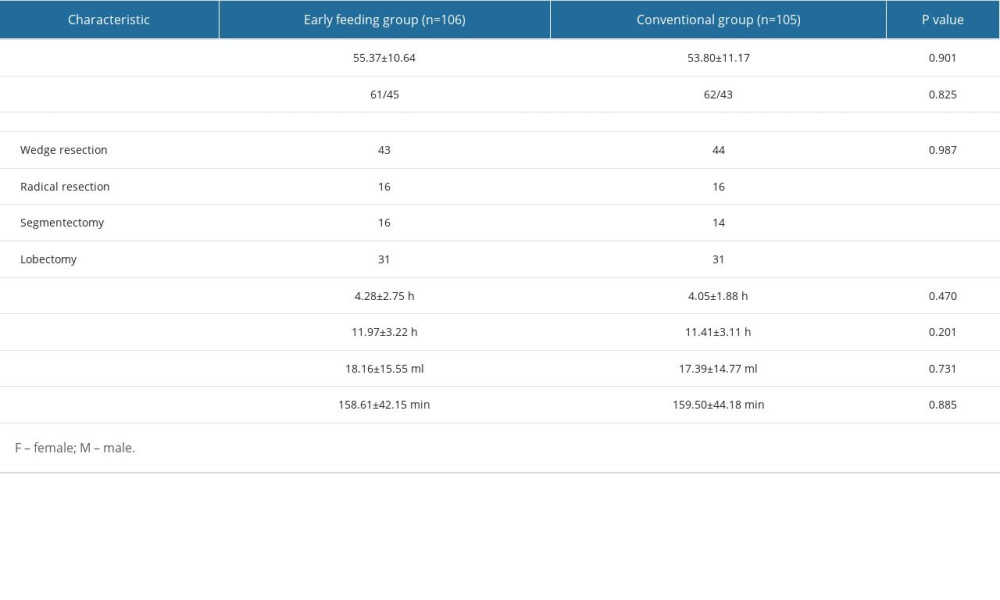

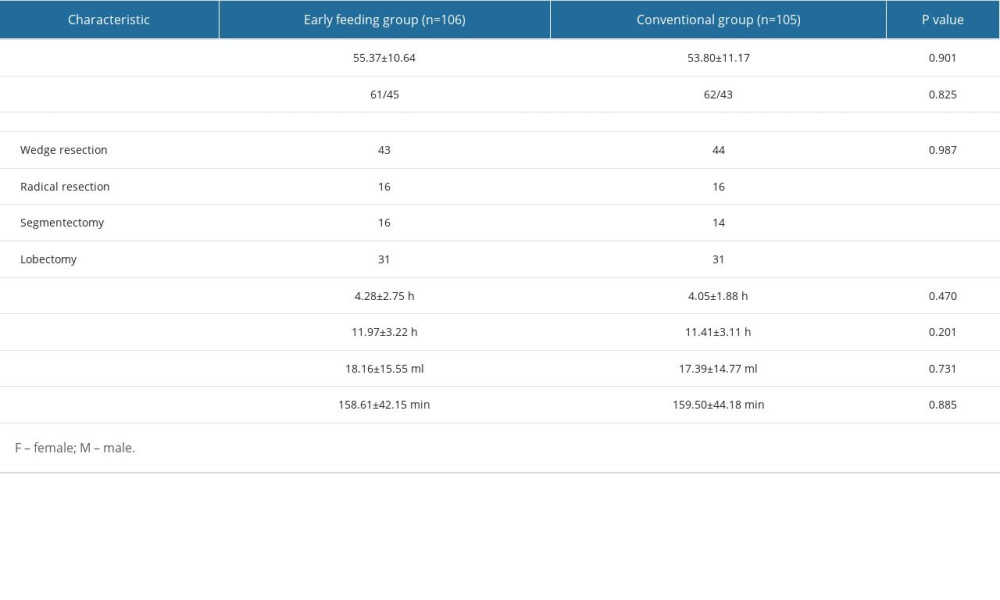

The sociodemographic and clinical features of the included patients are summarized in Table 1. The average age of the patients in the early feeding group was 55.37±10.59 years, whereas the average age in the conventional group was 53.80±11.12 years. There was no significant difference in age between the 2 groups (P =0.30). No difference was found in the preoperative duration of water deprivation or the duration of fasting between the early feeding group and the conventional group (P=0.470 and P=0.201, respectively). All enrolled patients were diagnosed with lung cancer; most underwent wedge resection (87/211), and the rest underwent radical resection (32/211), segmentectomy (30/211), or lobectomy (61/211). There were no significant differences between the intervention and conventional groups in patient age (P=0.901), sex ratio (P=0.825), and surgical procedures (P=0.987), and there was no significant no difference between the 2 groups in amount of intraoperative blood loss or duration of operation (P=0.731 and P=0.885, respectively).

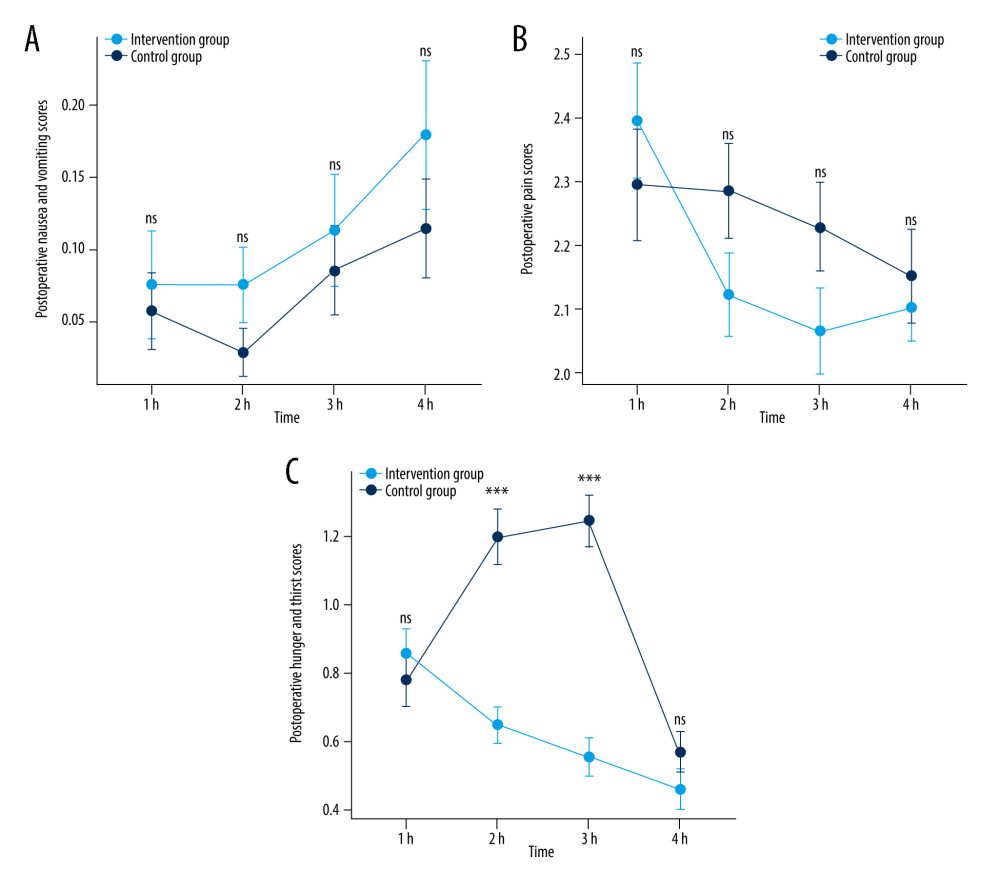

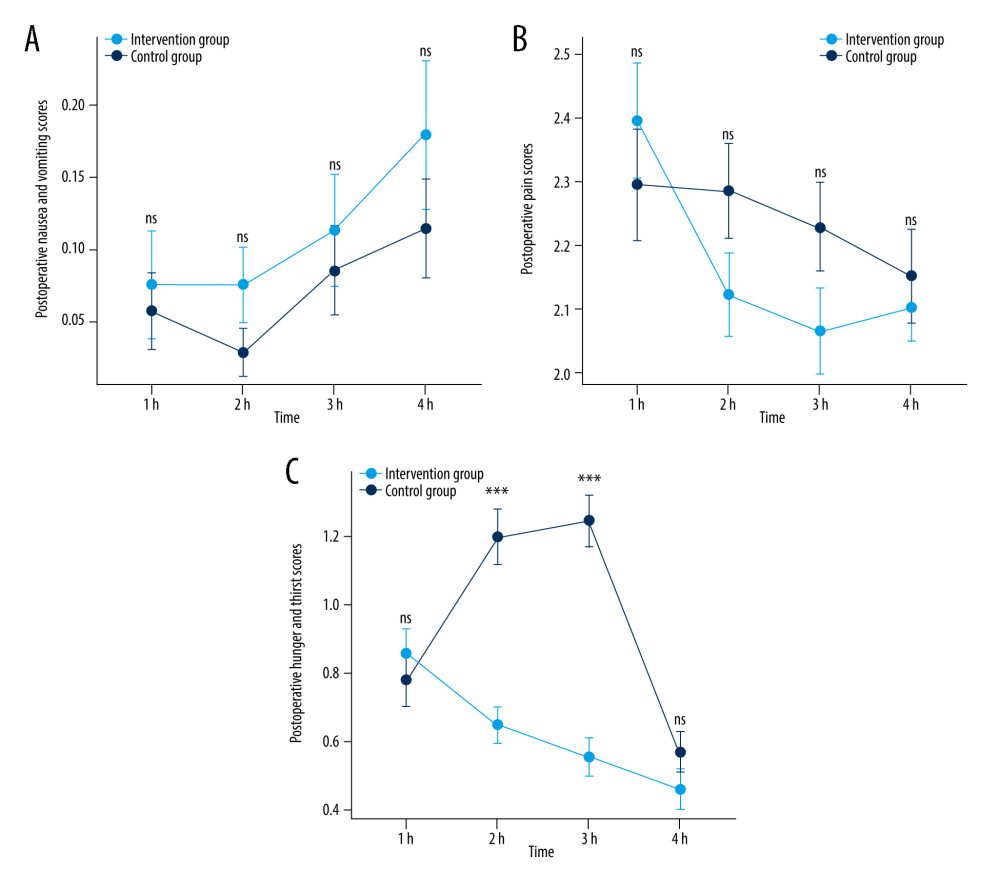

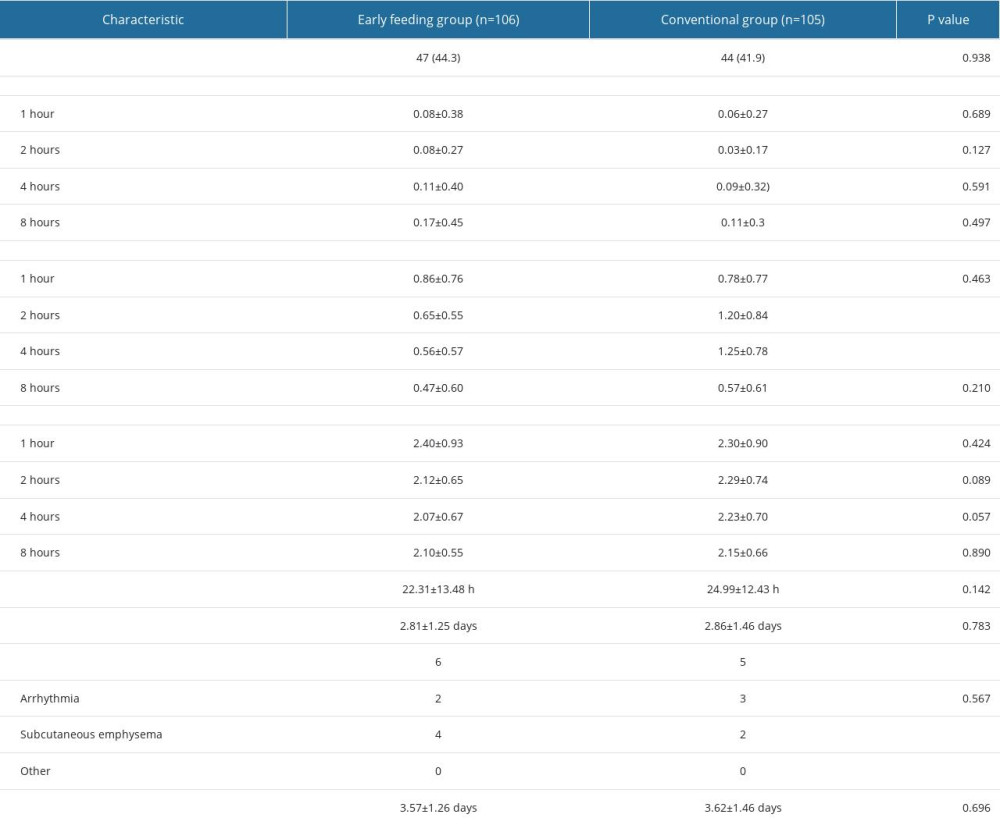

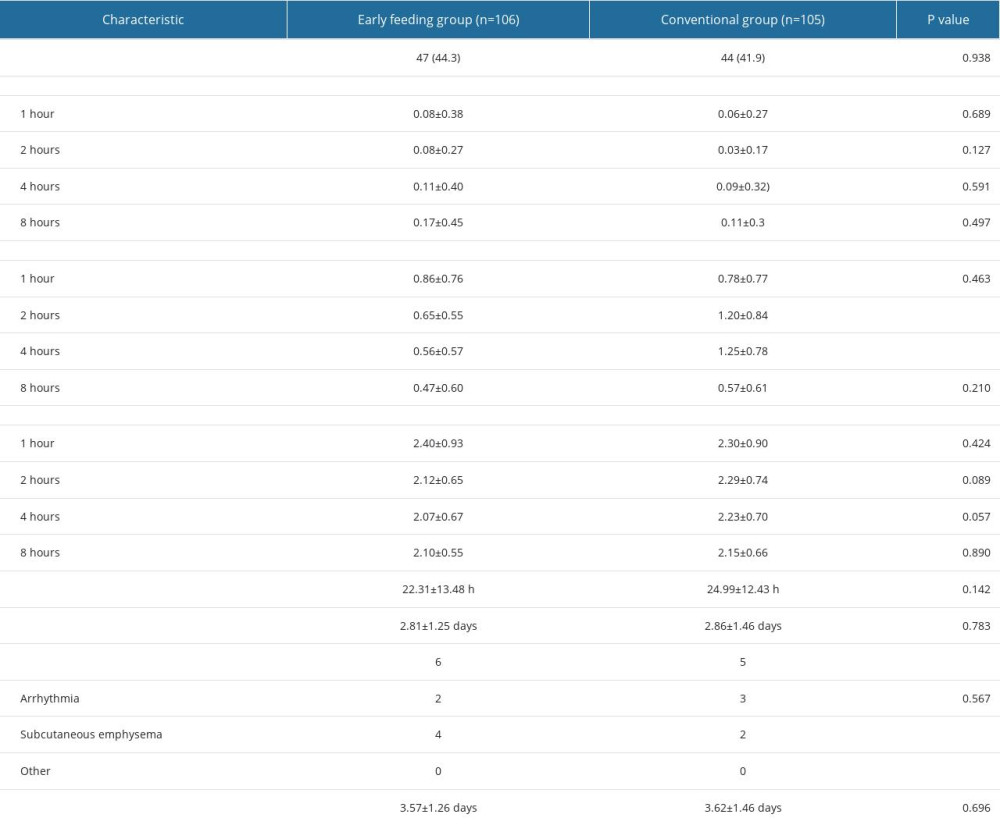

THE DEGREES OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA, VOMITING, AND PAIN: Data on the postoperative outcomes are shown in Table 2. No significant differences were found in the degrees of postoperative nausea and vomiting after extubation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 h (P=0.689, P=0.127, P=0.591, and P=0.497, respectively) (Figure 2A). There were no significant differences in pain between the 2 groups after extubation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 h (P=0.424, P=0.089, P=0.057, and P=0.890, respectively) (Figure 2B), and there was no significant difference between groups in time of first flatus (P=0.142).

THE DEGREES OF POSTOPERATIVE HUNGER AND THIRST SCORES: In terms of hunger and thirst scores, no difference was found in the scores after extubation for 1 h between the early feeding group and the conventional group (P=0.689). The hunger and thirst scores in the early feeding group decreased over time, while the scores in the conventional group tended to increase before feeding and then decreased after feeding (Figure 2C). However, the hunger and thirst scores after extubation for 2 h and 4 h were higher in the conventional group than in the early feeding group (both P<0.001). The hunger and thirst scores after extubation for 8 h did not differ between groups (P=0.210).

POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS AND OTHER MEASUREMENTS:

Postoperative complications included arrhythmia and subcutaneous emphysema. There were 2 patients with arrhythmia and 4 patients with subcutaneous emphysema in the early feeding group, while there were 3 patients with arrhythmia and 2 patients with subcutaneous emphysema in the conventional group. No difference was observed in the types of complications in the 2 groups (

Discussion

LIMITATIONS:

There were several limitations to our study. First, it was conducted in a specific cohort at a single center, limiting the applicability of the findings to other patient groups undergoing major surgery. To further evaluate and compare the feasibility of early feeding in thoracic surgery patients, larger multicenter randomized studies are needed. Second, this study did not specify the exact volume of food and drink consumed, and well-designed studies with larger sample sizes are needed to address this issue. Third, preoperative treatment like chemotherapy and radiotherapy might be confounding factors in the study. Last but not least, selection bias may still exist, since we excluded patients with operation time ≥4 h.

Conclusions

The current clinical routine of postoperative diet may cause patients to experience more hunger, thirst, and discomfort after surgery, which is not conducive to their fast-track rehabilitation. Early oral feeding after thoracoscopic lung cancer resection is safe. An early diet and drinking regimen cause no more adverse effects than a traditional diet and can be well tolerated, providing greater comfort and satisfaction to patients.

Figures

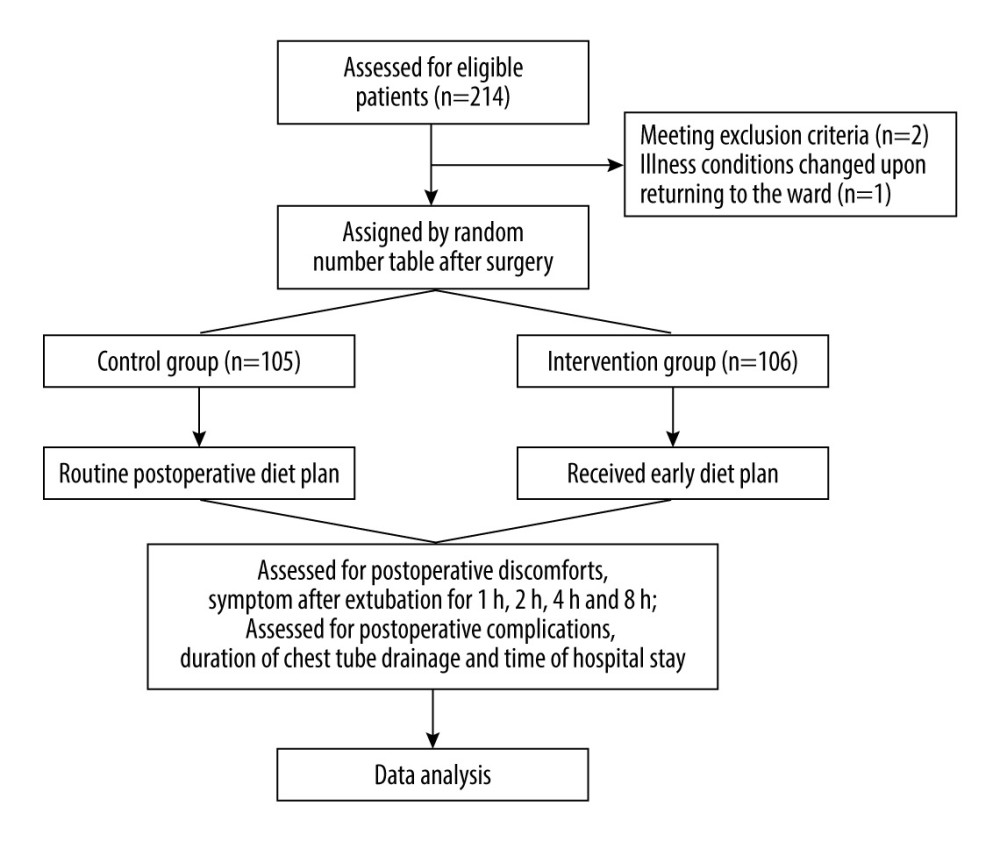

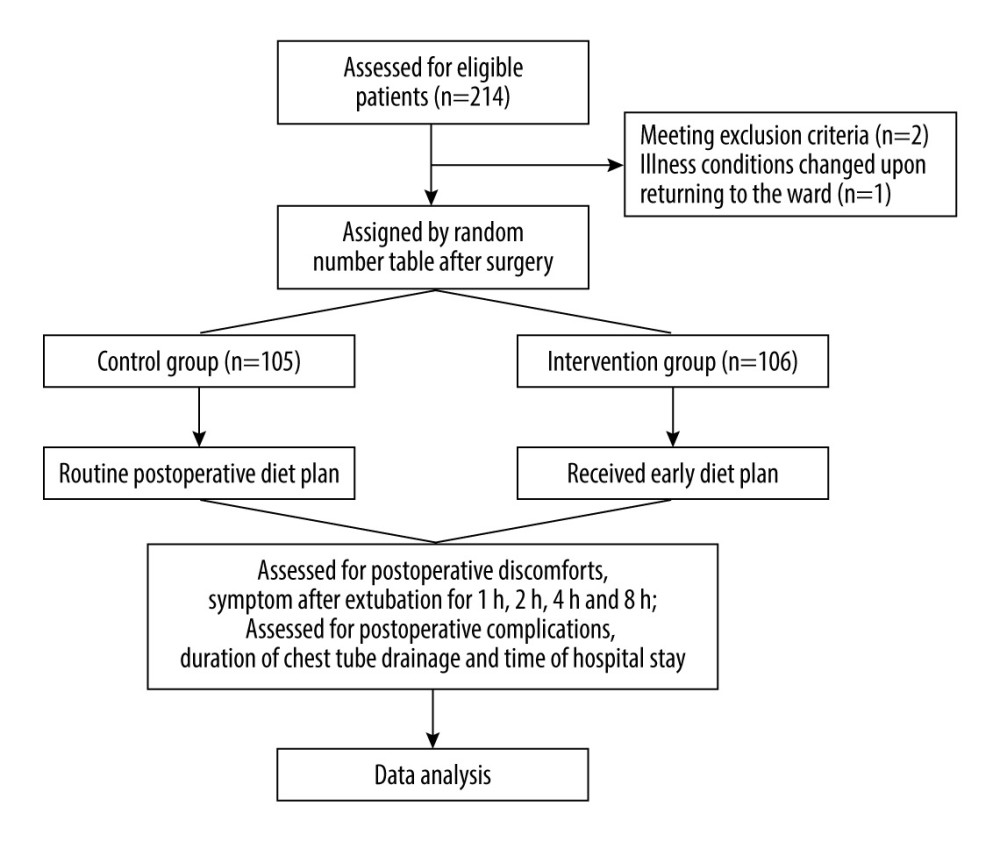

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the trial. Collectively, 211 patients were randomly divided – 105 were assigned to the conventional group and 106 were assigned to the intervention group. (Figure created using Power Point 2016).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the trial. Collectively, 211 patients were randomly divided – 105 were assigned to the conventional group and 106 were assigned to the intervention group. (Figure created using Power Point 2016).  Figure 2. Postoperative nausea and vomiting scores (A), pain scores (B), and hunger and thirst scores (C) over time. No differences were found in the degrees of postoperative nausea, vomiting and pain after extubation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 hours between the 2 groups. The hunger and thirst scores after extubation for 2 hours and 4 hours decreased and were lower in the early feeding group. ns – not significant; *** P<0.001. h – hour. (Data visualized via R package “stats”, “car” and “ggplot2”, version 4.2.1).

Figure 2. Postoperative nausea and vomiting scores (A), pain scores (B), and hunger and thirst scores (C) over time. No differences were found in the degrees of postoperative nausea, vomiting and pain after extubation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 hours between the 2 groups. The hunger and thirst scores after extubation for 2 hours and 4 hours decreased and were lower in the early feeding group. ns – not significant; *** P<0.001. h – hour. (Data visualized via R package “stats”, “car” and “ggplot2”, version 4.2.1). References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries: Cancer J Clin, 2021; 71(3); 209-49

2. Sihoe ADL, Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery as the gold standard for lung cancer surgery: Respirology, 2020; 25(Suppl 2); 49-60

3. Wang L, Ge L, Song S, Ren Y, Clinical applications of minimally invasive uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery: J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2023; 149(12); 10235-39

4. Sihoe ADL, Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery as the gold standard for lung cancer surgery: Respirology, 2020; 25(S2); 49-60

5. Tikka T, Hilmi OJ, Upper airway tract complications of endotracheal intubation: British journal of hospital medicine (London, England: 2005), 2019; 80(8); 441-47

6. Carli F, Clemente A, Regional anesthesia and enhanced recovery after surgery: Minerva Anestesiologica, 2014; 80(11); 1228-33

7. Madan S, Sureshkumar S, Anandhi A, Comparison of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathway versus standard care in patients undergoing elective stoma reversal surgery – a randomized controlled trial: J Gastrointest Surg, 2023 Online ahead of print

8. Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery: Clin Nutr, 2021; 40(7); 4745-61

9. Zhang W, Zhang Y, Qin Y, Shi J, Outcomes of enhanced recovery after surgery in lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs, 2022; 9(11); 100110

10. Hu X, He X, Enhanced recovery of postoperative nursing for single-port thoracoscopic surgery in lung cancer patients: Front Oncol, 2023; 13; 1163338

11. Khan M, Latifi R, Nutrition in surgical patients: How soon is too soon?: Curr Opin Crit Care, 2019; 25(6); 701-5

12. Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P, Preoperative fasting for adults to prevent perioperative complications: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2003(4); CD004423

13. Smith I, Kranke P, Murat I, Perioperative fasting in adults and children: Guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology: Eur J Anaesthesiol, 2011; 28(8); 556-69

14. Steenhagen E, Enhanced recovery after surgery: It’s time to change practice!: Nutr Clin Pract, 2016; 31(1); 18-29

15. Reintam Blaser A, Starkopf J, Alhazzani W, Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: ESICM clinical practice guidelines, 2017; 43(3); 380-98

16. Jiménez Jiménez FJ, Cervera Montes M, Blesa Malpica AL, Guidelines for specialized nutritional and metabolic support in the critically-ill patient: Update. Consensus SEMICYUC-SENPE: Cardiac patient: Nutr Hosp, 2011; 26(Suppl 2); 76-80

17. Dai W, Zhang Y, Feng W, Using patient-reported outcomes to manage postoperative symptoms in patients with lung cancer: Protocol for a multicentre, randomised controlled trial: BMJ Open, 2019; 9(8); e030041

18. Yan C, Xue C, Huqing L, Xiaojuan L, Comparison of the application value of Aldrete score, Steward score, and Observer’s Assessment of Alterness/Sedation score in recovery after daytime thoracoscopic surgery under general anesthesia: International Journal of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation, 2022; 43(9); 944-49

19. Osawa A, Maeshima S, Tanahashi N, Water-swallowing test: Screening for aspiration in stroke patients: Cerebrovasc Dis, 2013; 35(3); 276-81

20. Franklin HR, Simonetti GP, Dubbelman AC, Toxicity grading systems. A comparison between the WHO scoring system and the Common Toxicity Criteria when used for nausea and vomiting: Ann Oncol, 1994; 5(2); 113-17

21. Whisenant MS, Williams LA, Garcia Gonzalez A, What do patients with non-small-cell lung cancer experience? Content domain for the MD Anderson symptom inventory for lung cancer: JCO Oncol Pract, 2020; 16(10); e1151-e60

22. Yin X, Ye L, Zhao L, Li L, Song J, Early versus delayed postoperative oral hydration after general anesthesia: A prospective randomized trial: Int J Clin Exp Med, 2014; 7(10); 3491-96

23. Fuentes Padilla P, Martínez G, Vernooij RW, Early enteral nutrition (within 48 hours) versus delayed enteral nutrition (after 48 hours) with or without supplemental parenteral nutrition in critically ill adults: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019; 2019(10); CD012340

24. Deng H, Li B, Qin X, Early versus delay oral feeding for patients after upper gastrointestinal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: Cancer Cell Int, 2022; 22(1); 167

25. Osland E, Yunus RM, Khan S, Memon MA, Early versus traditional postoperative feeding in patients undergoing resectional gastrointestinal surgery: A meta-analysis: JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2011; 35(4); 473-87

26. Yi HC, Ibrahim Z, Abu Zaid Z, Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery with preoperative whey protein-infused carbohydrate loading and postoperative early oral feeding among surgical gynecologic cancer patients: An open-labelled randomized controlled trial: Nutrients, 2020; 12(1); 264

27. Mercan A, El-Kerdawy H, Bhavsaar B, Bakhamees HS, The effect of timing and temperature of oral fluids ingested after minor surgery in preschool children on vomiting: A prospective, randomized, clinical study: Paediatr Anaesth, 2011; 21(10); 1066-70

28. Cheng W, Chow B, Tam PK, Electrogastrographic changes in children who undergo day-surgery anesthesia: J Pediatr Surg, 1999; 34(9); 1336-38

29. Paul S, Altorki NK, Sheng SB, Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity than open lobectomy: A propensity-matched analysis from the STS database: J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2010; 139(2); 366-78

30. Bayman EO, Parekh KR, Keech J, A prospective study of chronic pain after thoracic surgery: Anesthesiology, 2017; 126(5); 938-51

31. Hong Z, Lu Y, Li H, Effect of early versus late oral feeding on postoperative complications and recovery outcomes for patients with esophageal cancer: A systematic evaluation and meta-analysis: Ann Surg Oncol, 2023 Online ahead of print

Figures

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the trial. Collectively, 211 patients were randomly divided – 105 were assigned to the conventional group and 106 were assigned to the intervention group. (Figure created using Power Point 2016).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the trial. Collectively, 211 patients were randomly divided – 105 were assigned to the conventional group and 106 were assigned to the intervention group. (Figure created using Power Point 2016). Figure 2. Postoperative nausea and vomiting scores (A), pain scores (B), and hunger and thirst scores (C) over time. No differences were found in the degrees of postoperative nausea, vomiting and pain after extubation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 hours between the 2 groups. The hunger and thirst scores after extubation for 2 hours and 4 hours decreased and were lower in the early feeding group. ns – not significant; *** P<0.001. h – hour. (Data visualized via R package “stats”, “car” and “ggplot2”, version 4.2.1).

Figure 2. Postoperative nausea and vomiting scores (A), pain scores (B), and hunger and thirst scores (C) over time. No differences were found in the degrees of postoperative nausea, vomiting and pain after extubation for 1, 2, 4, and 8 hours between the 2 groups. The hunger and thirst scores after extubation for 2 hours and 4 hours decreased and were lower in the early feeding group. ns – not significant; *** P<0.001. h – hour. (Data visualized via R package “stats”, “car” and “ggplot2”, version 4.2.1). Tables

Table 1. Baseline demographics and surgical characteristics of the early feeding group and conventional group.

Table 1. Baseline demographics and surgical characteristics of the early feeding group and conventional group. Table 2. Postoperative discomfort assessment and clinical characteristics of the early feeding group and conventional group.

Table 2. Postoperative discomfort assessment and clinical characteristics of the early feeding group and conventional group. Table 1. Baseline demographics and surgical characteristics of the early feeding group and conventional group.

Table 1. Baseline demographics and surgical characteristics of the early feeding group and conventional group. Table 2. Postoperative discomfort assessment and clinical characteristics of the early feeding group and conventional group.

Table 2. Postoperative discomfort assessment and clinical characteristics of the early feeding group and conventional group. In Press

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) and 3 (TIMP-3) as New Markers of Acute Kidney Injury Afte...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943500

12 Mar 2024 : Review article

Optimizing Behçet Uveitis Management: A Review of Personalized Immunosuppressive StrategiesMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943240

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Metabolomic Alterations in Methotrexate Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe PsoriasisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943360

14 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Renal Dysfunction Increases Risk of Adverse Cardiovascular Events in 5-Year Follow-Up Study of Intermediate...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943956

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952