16 November 2023: Clinical Research

Psychometric Properties of the Polish Version of the FACIT-Sp-12: Assessing Spiritual Well-Being Among Patients with Chronic Diseases

Michał MachulDOI: 10.12659/MSM.941769

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e941769

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Spirituality plays a crucial role in enhancing quality of life. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp) scale is a reliable tool to assess an individual’s spiritual well-being, specifically in the context of chronic illness. Although the instrument is widely used worldwide, it has not yet been validated for Polish conditions. The aim of this study was to translate and investigate the reliability and validity of the Polish version of the FACIT-Sp-12 and examine whether it is associated with measures of religiosity and religious practice.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The self-administered FACIT-Sp questionnaire, containing 12 spiritual well-being items, was translated into the Polish language, following the FACIT multilingual translation methodology. A group of 355 patients with chronic diseases were enrolled. Validation analysis was conducted. The reliability of the scale and subscales was evaluated with internal consistency coefficients.

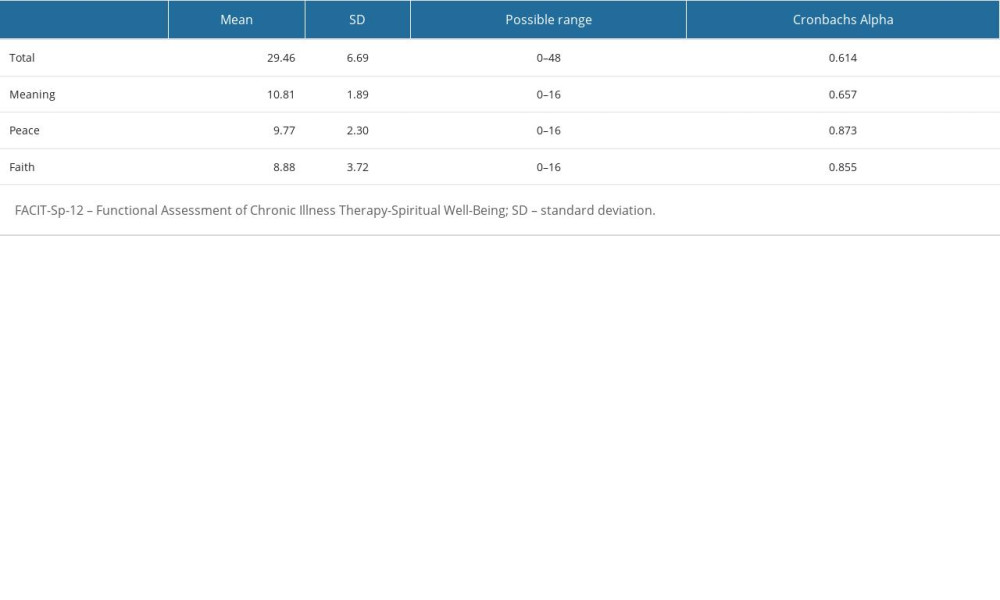

RESULTS: A confirmatory factor analysis corroborated a 3-factor model (Meaning, Peace, and Faith) of the FACIT-Sp-12 Polish version, which showed moderate internal consistency. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.614 for the overall scale, 0.657 for the Meaning subscale, 0.873 for the Peace subscale, and 0.855 for the Faith subscale. The mean score was 29.46 (SD=6.69) for the overall spiritual well-being scale. Total scores of the FACIT-Sp-12 were strongly correlated with the Polish version of the Duke University Religion Index.

CONCLUSIONS: The psychometric properties of the Polish version of the FACIT-Sp-12 were satisfactory, and the scale can be used in Poland for assessing the spiritual well-being of patients with chronic illness.

Keywords: Chronic Disease, Health Personnel, Needs Assessment, Spirituality, Validation study

Background

In recent decades, spirituality has become recognized as vital in patient-centered care [1–4]. Spirituality is a term that is difficult to define unequivocally. Therefore, there are many definitions of this concept in the literature [5,6]. Puchalski’s definition is considered to be the universally accepted and most widespread. She defines spirituality as “the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connection to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred” [5]. Many researchers have explored the connection between patient-reported health outcomes and spirituality, especially in mental health and oncology clinical settings, and among patients with chronic illness [7–10]. It is important to differentiate between organized religion and spirituality to maximize its application across cultures and communities. While organized religion may be a subcomponent of spirituality, the latter refers to the notion that a greater power or life force connects all humanity. In this aspect, some studies have associated increased happiness levels with spirituality, arguing that people who believe their lives have meaning and purpose are generally happier than their non-spiritual counterparts [11–13]. At this point, it is generally believed that spirituality plays a critical role in influencing patients’ adaptation to minimize the impact of negative health situations. Spirituality, as one of the most profound human needs, can be a fundamental component of healthy living [14,15].

Spiritual assessment is important in managing chronic disorders because it ensures that patients’ spiritual concerns, including fears or concerns about the outcome of interventions, are addressed. One of the benefits of conducting a spiritual assessment is that it can guide clinicians on when to take no further action [16,17]. In this respect, experienced clinicians are often expected to acknowledge when there is little they can provide patients regarding medical cures or solutions. Spiritual concerns and questions often affect the quality of a patient’s suffering despite not having clear answers or solutions in most cases. By conducting a spiritual assessment, physicians and nurses can appreciate their compassion, acceptance, understanding, and presence as essential therapeutic interventions for patients with chronic illnesses [18].

Identifying and understanding patient needs is one of the fundamental aspects of patient-centered care [19]. Clinicians should administer spiritual assessments to be able to provide spiritual care effectively [18,20,21]. The spiritual assessment allows healthcare experts to help patients identify and mobilize their spiritual resources to prevent the exacerbation of medical conditions. Acute exacerbations are common in cancers, HIV, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other chronic diseases [22–24]. Experienced medical personnel, who are able to make appropriate interventions in relation to the identified spiritual needs of patients, contribute not only to ensuring the comfort and inner peace of the individual, but also, through their interventions, are able to minimize the impact of chronic disorders on the deterioration of quality of life [25,26].

At the same time, they need to be trained to categorize patient needs, primarily spiritual and religious ones [25–27]. Most importantly, clinicians must be able to relate to people with different personalities and belief systems by maintaining a broad understanding of spirituality. They should also understand that they must remain engaged and positive to empower patients and others in life-threatening situations [28].

There are several tools available to make spiritual assessment possible in clinical practice, including the FICA, FAITH, SPIRITual, or HOPE tools, which use a qualitative approach [29]. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy, Spiritual Well-Being Scale 12 (FACIT-Sp-12) is one of the most widely recognized quantitative tools for conducting spiritual well-being assessments [30] among patients with cancer and other chronic disorders [31]. However, there is still a need to assess the validity and reliability of the FACIT-Sp-12 to understand its role across various groups and in countries with different cultural and religious groups [31,32]. At the time, there is a lack of a brief and valid instrument in the Polish language that assesses spirituality in patients with chronic diseases. The aim of the present study was to translate, linguistically validate, and test the factorial validity and internal consistency of the Polish version of the FACIT-Sp-12 among patients with chronic diseases and examine whether the FACIT-Sp-12 is differentially associated with measures of religiosity and religious practice.

Material and Methods

STUDY DESIGN:

A cross-sectional study was performed in 2022 in accordance with the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [33].

INSTRUMENTS:

Three instruments were used in the study:

TRANSLATION AND CULTURAL ADAPTATION OF THE POLISH VERSION OF FACIT-SP-12:

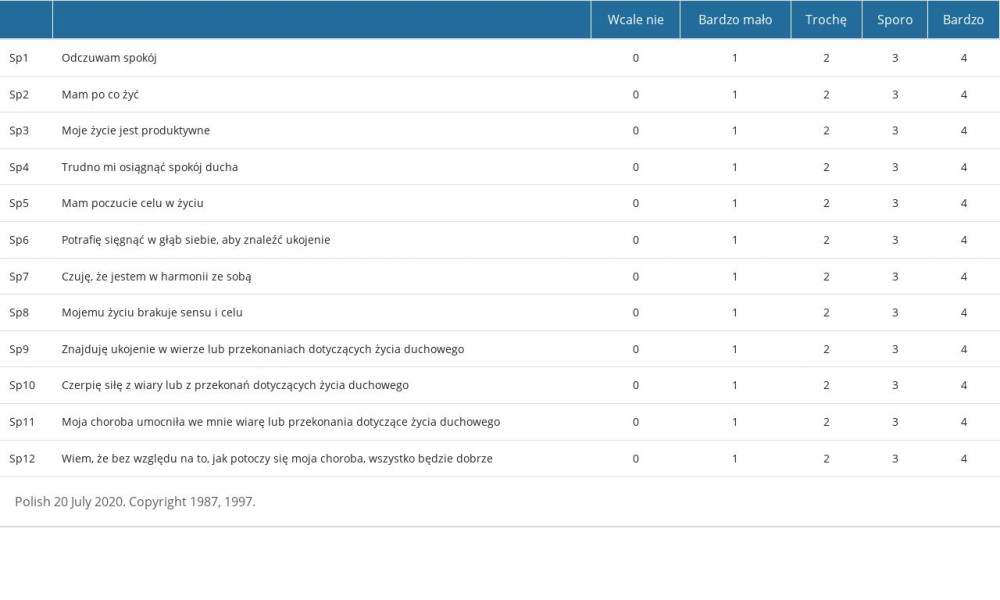

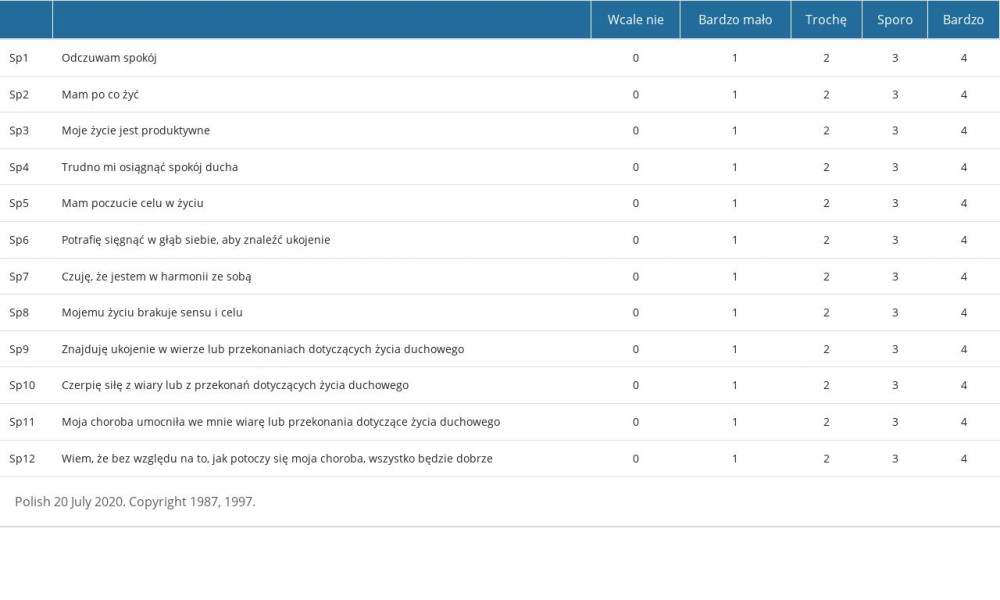

The FACIT-Sp-12 was translated into Polish in accordance with the FACIT multilingual translation methodology, which was developed to ensure that resulting translations of quantitative measures reflect conceptual equivalence with the source document rendered in language that is culturally acceptable and relevant to the target population and is consistent with consensus opinion [42]. In this case, conceptual equivalence refers to unbiased measurement between 2 translated instruments, so that any differences detected in responses are the result of differences between the groups being assessed [43]. The importance of equivalence is 2-fold: to compare results of different cultural and national groups using the same measure, and to pool data using the same measure across countries to assess differences on a larger scale, such as a clinical trial setting. The FACIT translation methodology, adopted by the HealthMeasures family of measurement systems (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS); Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders (Neuro-QoL); and NIH Toolbox, [44] is described as follows: 2 forward translations from English into the target language by native speakers of the target language, a reconciled version of the 2 forward translations completed by a third independent translator who is a native of the target language, a back-translation of the reconciled version by an English speaker fluent in the target language, harmonization of the translation with previously developed translations, and a final review by a native-speaking linguist or HRQL research expert. In the case of translation of the FACIT-Sp-12 into Polish, the whole process lasted 2 years and was guided by the person responsible from the FACIT group. Following the abovementioned process, a pre-test Polish version of FACIT-Sp-12 was linguistically validated with a small population of 10 patients, who completed the pre-test version of the measure and were interviewed using a debriefing script to confirm the suitability of the translated items. During the interviews, patients were asked to comment on the clarity and comprehensibility of the items from the instrument and to indicate any difficulties encountered in answering the questions. The results of the interviews were reviewed, and it was concluded the Polish translation was a linguistically valid equivalent of the original English. A translation of the FACIT-Sp-12 into Polish was certified by FACIT.org. The 12 items of the Polish version of the FACIT-Sp scale can be found in Table 1.

SAMPLE FOR VALIDITY STUDY:

A convenience sampling method was used to select the study group. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 18 years or older, (2) diagnosis of chronic illness at least 1 year ago, (3) inpatient at clinical follow-up for 1 week, (4) health condition that allows participation in a study, (5) ability to read/write Polish, and (6) consent to participate in this study.

DATA COLLECTION:

This study was conducted in the period of 11 months from October 2021 to September 2022 on patients who met the inclusion criteria and were hospitalized in a clinical hospital in the eastern part of Poland. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants. The study adopted the definition of chronic diseases according to the classification of the Department of Health’s Division of Chronic Disease Prevention [45]. The study recruited patients with heart disease, arthritis, cancer, diabetes, asthma, and Crohn disease. Patients were recruited in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit, and in the Pulmonology, Cardiology, Endocrinology, Rheumatology, Gastrology, and Oncology Departments, where chronic diseases are treated. The collection of data depended on the availability of patients in a given ward and epidemiological restrictions, as the study was conducted during the coronavirus epidemic. The completed questionnaires were collected by the researcher. After receiving a copy of the informed consent form and providing written consent, participants were asked to complete the FACIT-Sp privately and without assistance. Participants self-reported their socio-demographic data; the researcher, using the patient’s medical history, supplemented the data of the main diagnosis and the reason for hospitalization with the patient’s consent. Questionnaires from 355 patients with chronic diseases were collected.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The study group was characterized by the structure index, median, mean, dispersion measures, and standard deviation. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA, principal component analysis) was used to investigate instrument dimensionality. The Kaiser-Meyer Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and the Bartlett test of sphericity were analyzed first to determine suitability of the data to undergo factor analysis; the cut off was >0.6. The Quartimax rotation was performed. Factor loadings larger than 0.3 within a particular dimension were considered to support its factor construction.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to confirm the structure of the scale. To evaluate model fit, this study used a range of absolute and incremental model fit indices, including the relative chi-square (CMIN/df, <2 as good fit), comparative fit index (CFI, >0.95 as excellent), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI, >0.90 as acceptable), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, <0.06 as good), and the standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR, <0.08 as acceptable), and the test of close fit (PCLOSE, ≤0.5; the value of PCLOSE associated with RMSEA should be greater than 0.05 to ensure a close fit). Some authors [34] suggest that 100 respondents are the absolute minimum number required to undertake CFA. Others suggest that an adequate sample size for CFA is considered a minimum of 200 [46]. There is also a rule of thumb of 5 respondents per item. However, strict rules on sample size have mostly disappeared [47]. The participants for the CFA consisted of 61 ill patients randomly selected from the patients who participated in the study [35].

Internal consistency of the FACIT-Sp-12 items was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.7 or higher was generally considered to be sufficient to demonstrate internal consistency. Correlations between variables, depending on the level of variable measurement, were assessed using Pearson’s r or Spearman’s rho. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) and AMOS version 29.0 was used for statistical analysis of the data (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

ETHICAL ISSUES:

The approval of the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Lublin (No.: KE-0254/289/2020) was obtained to conduct the study. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Permission to use the FACIT-Sp was obtained from the FACIT group. All participants were informed about the course of the study and provided written informed consent. They could withdraw from the study at any time if they felt lack of comfort or for any other reason. Collected data were coded to protect patients’ privacy and maintain their anonymity.

Results

STUDY PARTICIPANTS:

The study included 355 chronically ill patients. The Department of Health’s Division of Chronic Disease Prevention classification was adopted as the definition of chronic diseases [45]. The patients’ demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The majority of patients were female (61.4%). The mean age of the respondents was 58 years. Most (76%) were married or had a partner. Approximately a quarter (24.8%) had completed primary school, 20.6% had a vocational degree, 32.1% had graduated high school, and 22.5% had a university degree. The most common chronic diseases were heart diseases (44.3%), diabetes (9.6%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8.2%). The sample of the population of patients with chronic diseases obtained in the study seemed to be representative of the Polish population and similar to the results obtained in the National Health Test of Poles, in which 43% had heart disease, 9% had diabetes, and 3% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [48]. Study participants had a chronic disease for 1 to 32 years. The average duration of patients’ disease was 5.18 years, and 10.7% had a medical certificate of disability. Most participants reported religious affiliation, with 88.7% Catholic and 7.6% non-believers.

FACTOR STRUCTURE:

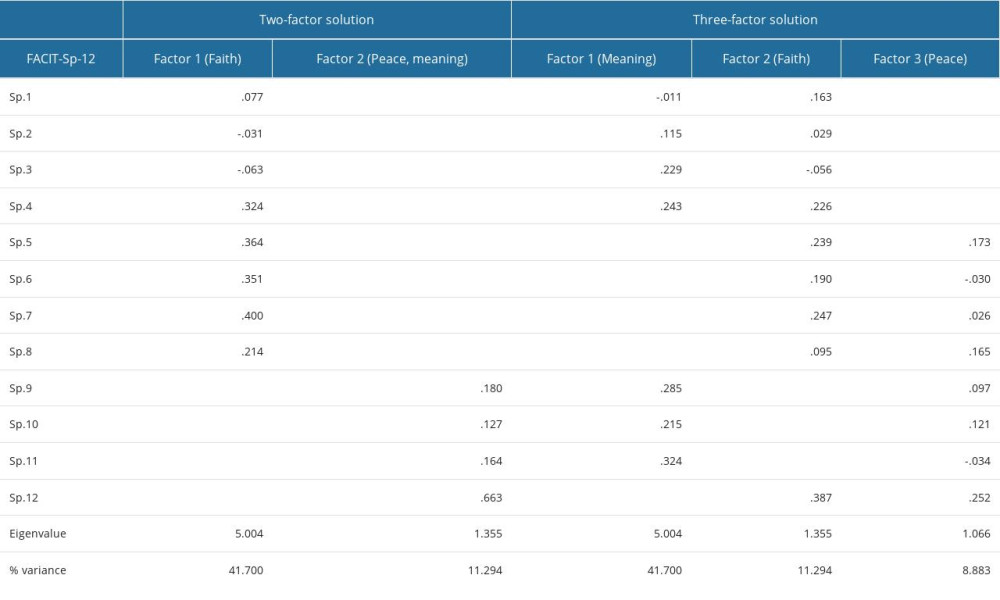

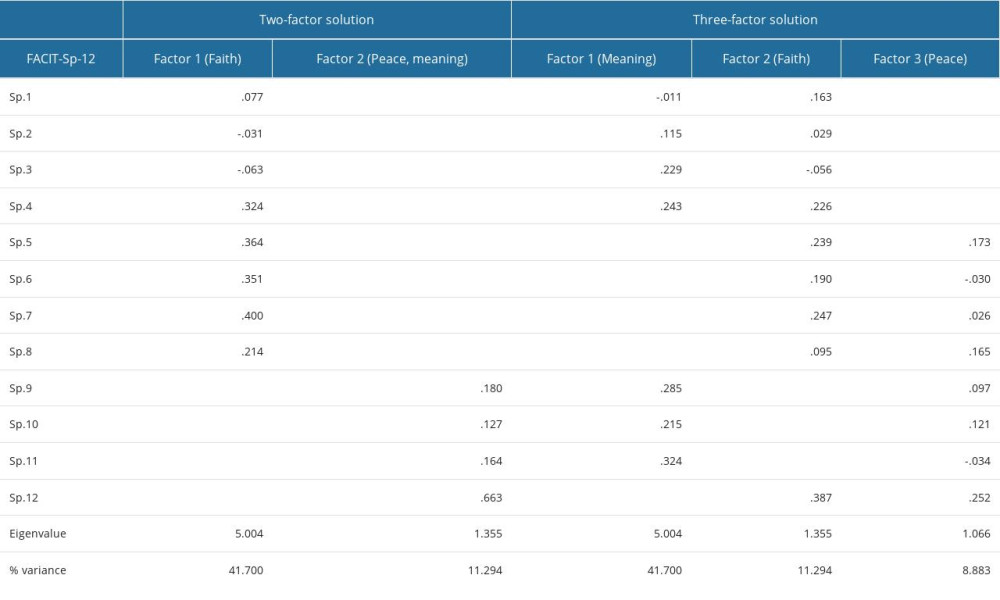

Factor analysis was used to explore construct validity of the questionnaire. For extracting the factors, principal components analysis with the Quartimax rotation method was used. The value of the Kaiser-Meyer Olkin index (KMO=0.838) and the statistical significance of the Bartlett test of sphericity (χ2 (66)=2037.276, P<0.001) suggested that there was sampling adequacy, and applying factor analysis would give satisfactory results. The factor analysis resulted in 2 factors, with Eigenvalue >1 (Kaiser criterion) that interpreted 53% of the total variance. All item loadings in factors had values >0.40. The 2-factor solution fully corresponds to the initial questionnaire. The Faith factor had an Eigenvalue of 5.004 and interpreted 41.70% of the total variance (questions 9, 10, 11, 12). The Peace and Meaning factor had an Eigenvalue of 1.355 and interpreted 11.29% of the total variance (questions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). In view of the divergent results obtained in the literature regarding the factor structure of the FACIT-Sp12 (3- or 2-factor models) a 3-factor solution was tested [48]. The results obtained were not consistent with the initial questionnaire. The Meaning factor had an Eigenvalue of 5.004, and interpreted 41.70% of the total variance (questions 5, 6, 7, 8, 12). The Faith factor had an Eigenvalue of 1.355, and interpreted 11.29% of the total variance (questions 9, 10, 11). The third factor, Peace, had an Eigenvalue of 1.066 and interpreted 8.88% of the total variance (questions 1, 2, 3, 4; Table 3.).

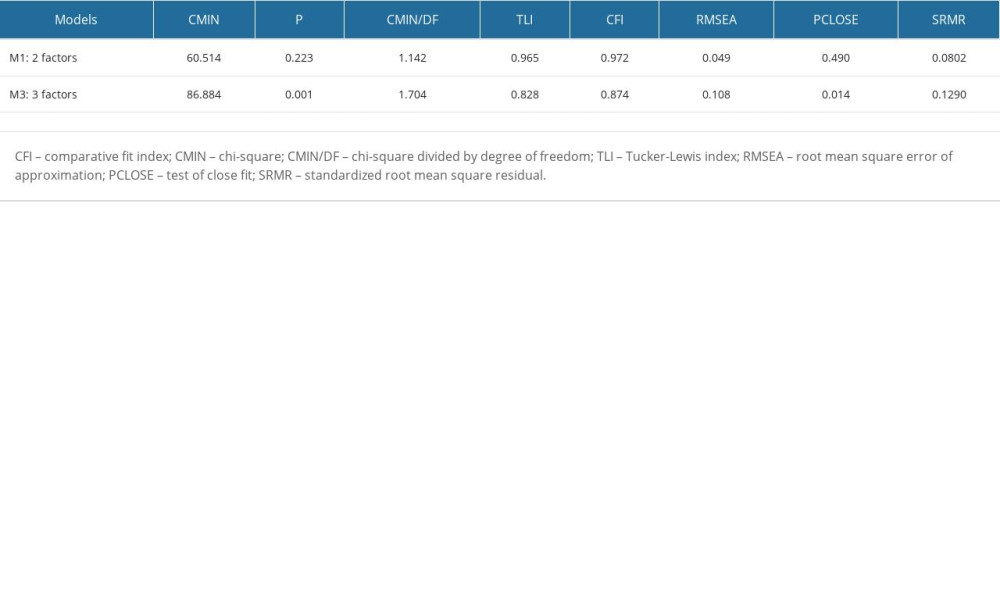

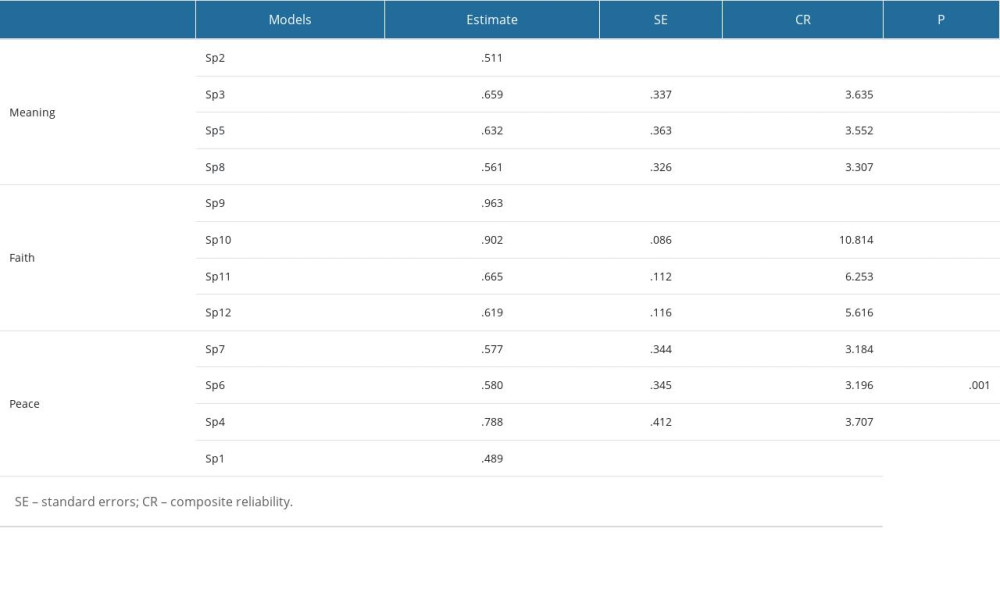

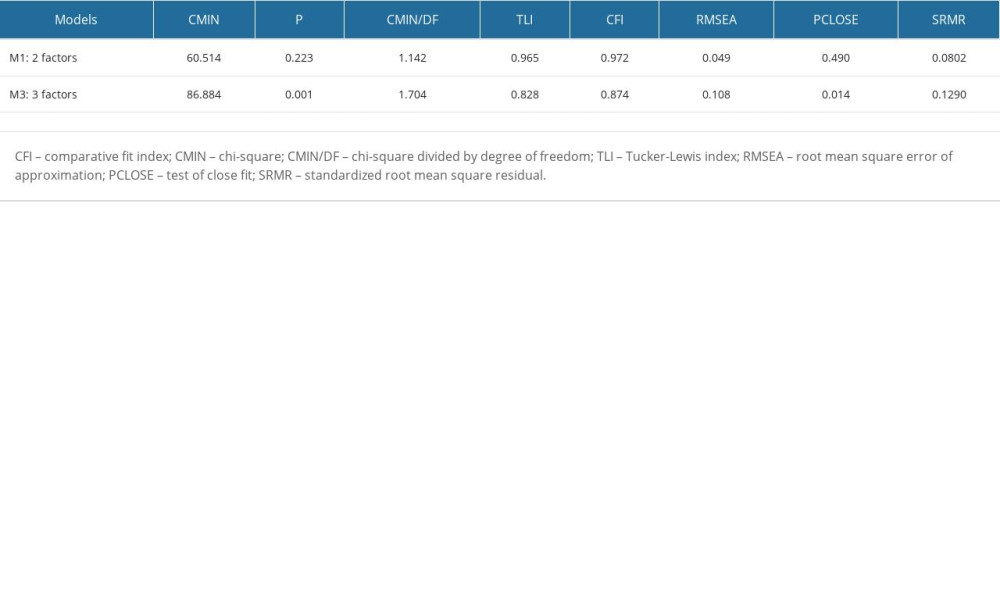

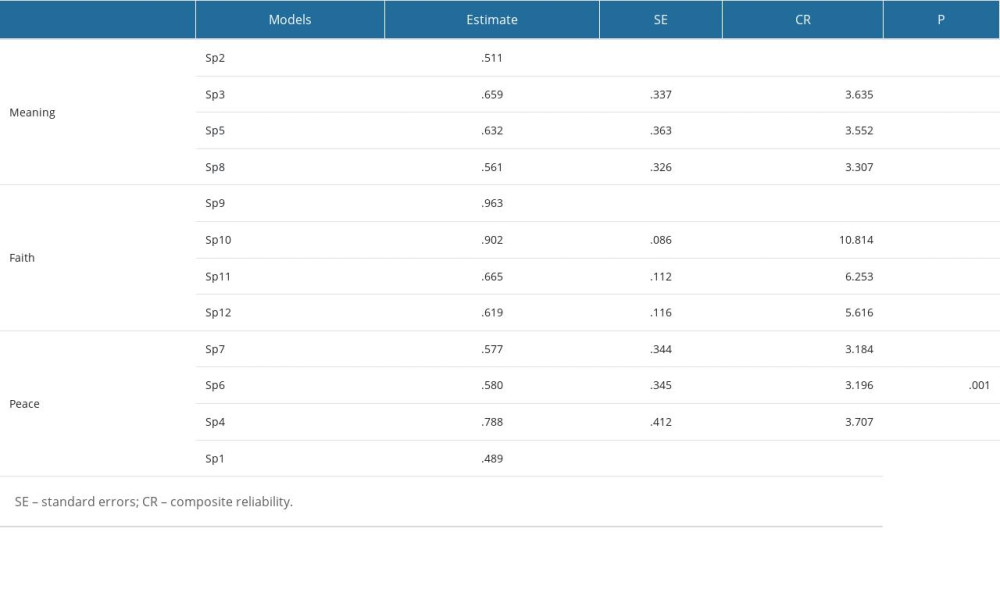

CFA was conducted to confirm the structure of the scale. Table 4 shows the fit measures of the 2 models tested (M1: 2 factors and M2: 3 factors). For both models, the indices were not acceptable. In the case of model 1 (2-factor solution) the PCLOSE was below 0.50 and the SRMR was above 0.80. In the case of model 2 (3-factor solution), the TLI and the CFI were both below 0.90, and the RMSEA was higher than 0.08. Therefore, CFA was used to test whether the hypothesized factor structure fitted the data [39]. The TLI and the CFI were both above 0.95, the RMSEA was below 0.06, the PCLOSE was higher than 0.50, and the SRMR was below 0.08. The results of the CFA support the 3-factor original structure for the FACIT-Sp12. Standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.49 to 0.96 (Table 5.). The Polish FACIT-Sp-12 corresponds to the structure of the original questionnaire.

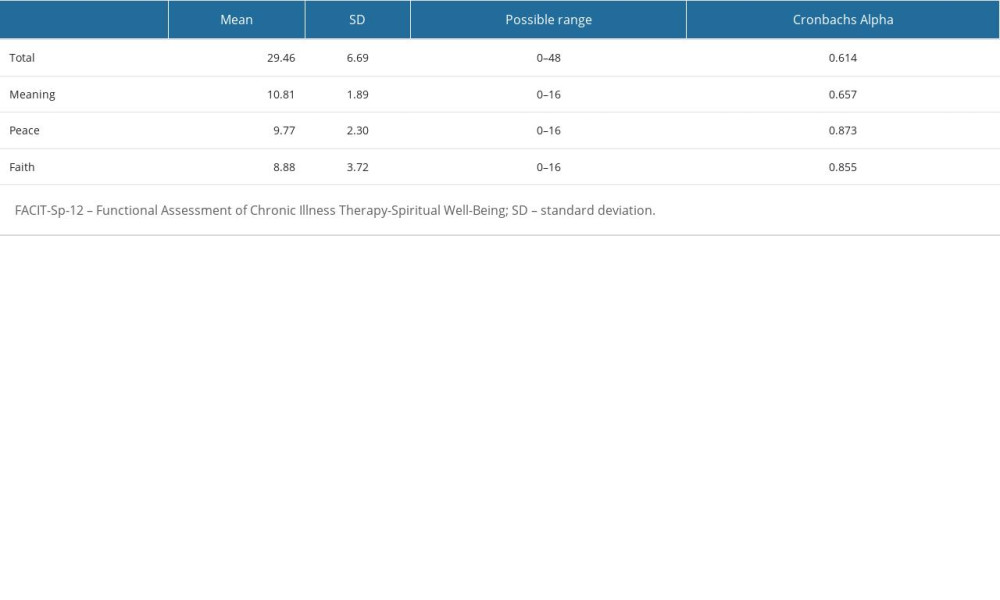

INTERNAL CONSISTENCY:

The means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficients of the FACIT-Sp-12 scales are displayed in Table 6. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as a measure of internal consistency. The total FACIT-Sp-12 scale and its subscales showed moderate and acceptable internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha value for the total scale was 0.614, Meaning subscale was 0.657, Peace subscale was 0.873, and Faith subscale was 0.855.

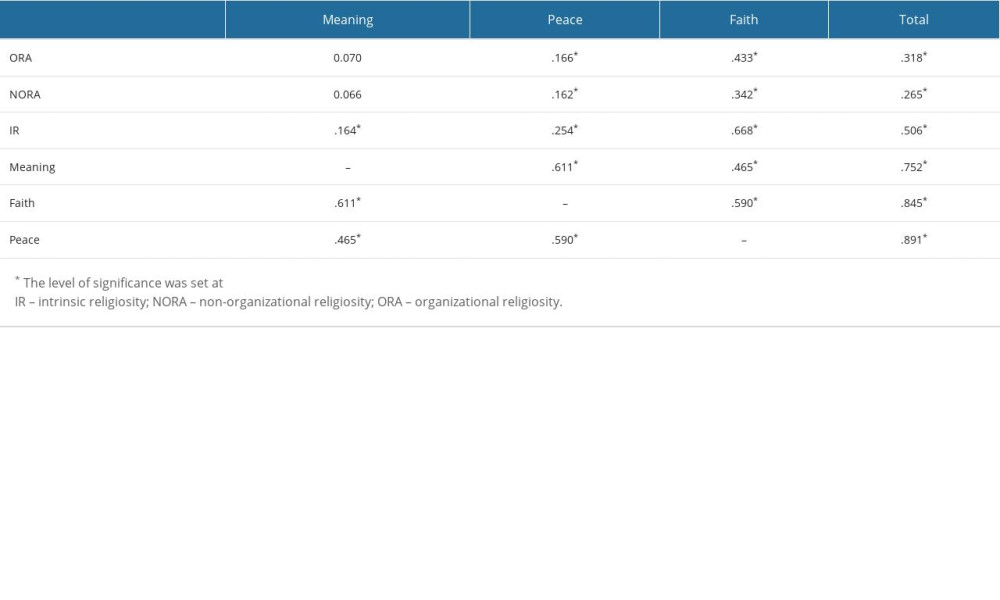

DISCRIMINANT AND CONVERGENT VALIDITY:

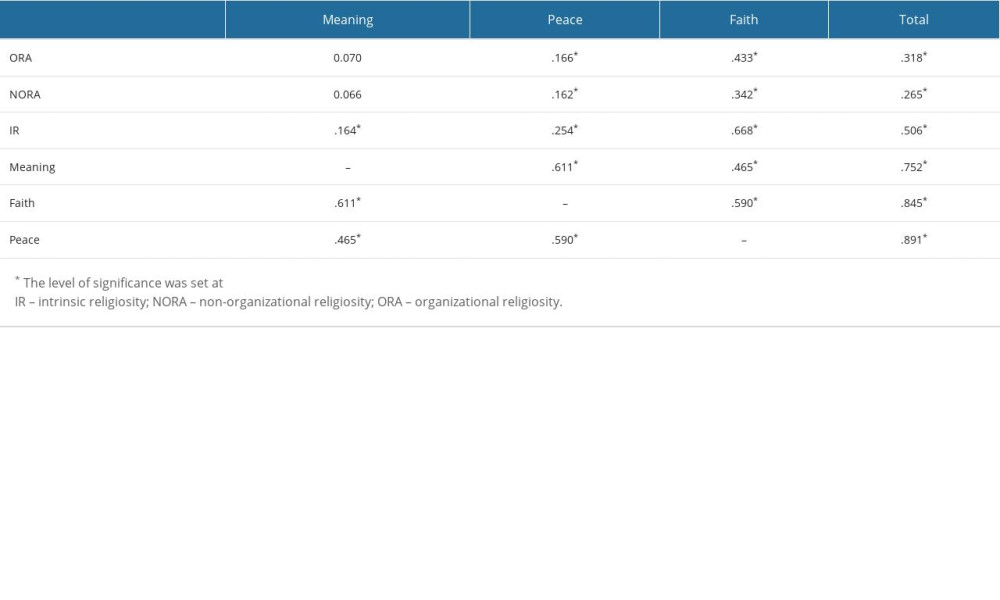

In relation to the data collected with the PolDUREL, it was shown that there were weak correlations between non-organizational religiosity with the FACIT-Sp scale and subscales, indicating a difference between spirituality and religiosity. Organizational religiosity showed a moderate correlation with the Faith subscale. Only intrinsic religiosity, which is considered closer to spirituality, showed a moderate correlation with the Faith subscale and the overall FACIT-Sp-12 score. The correlations between the subscales were moderate and statistically significant (P<0.001), the subscales and total score of FACIT-Sp-12 were strongly correlated (P<0.001; Table 7).

SPIRITUAL WELL-BEING OF POLISH PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC ILLNESS:

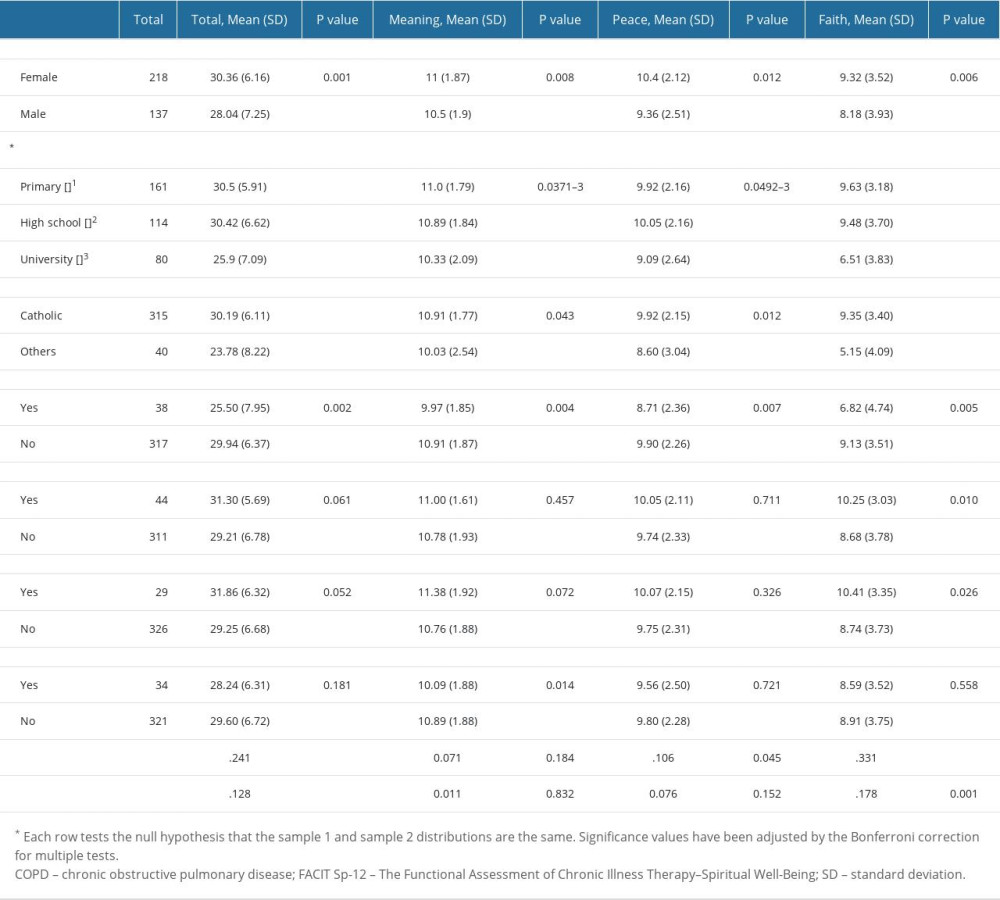

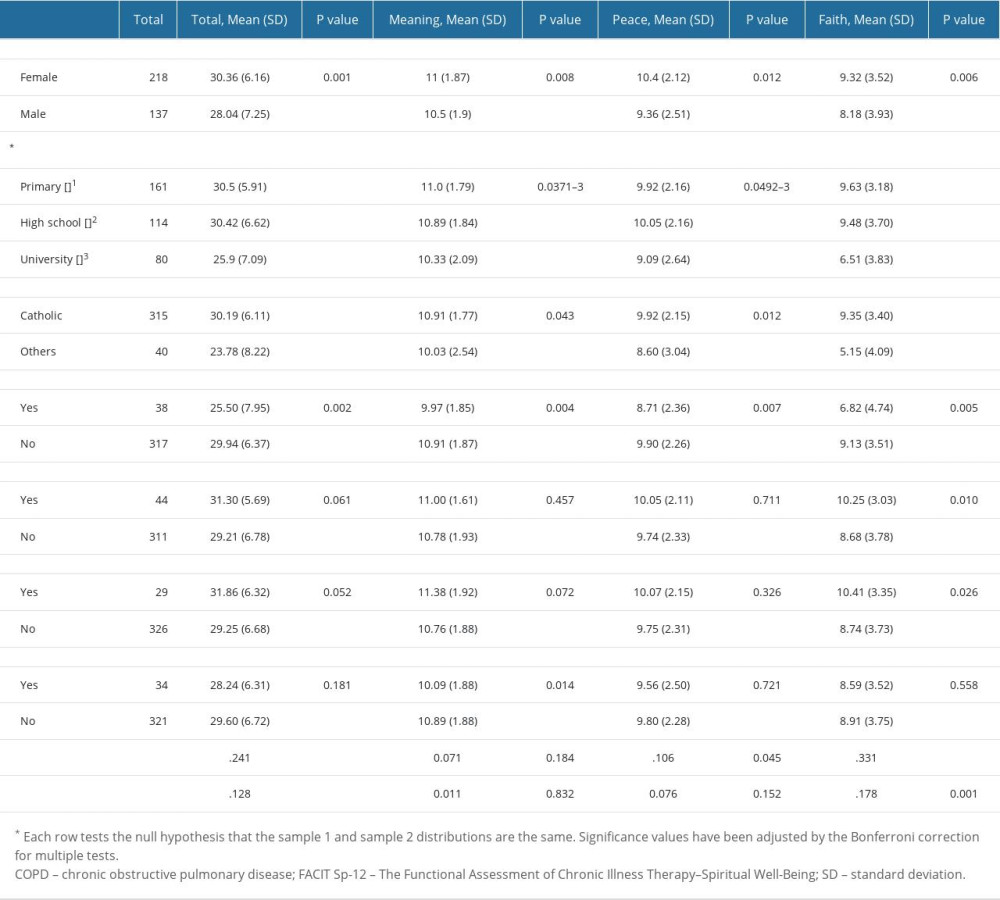

The average score obtained by the respondents on the FACIT-Sp-12 was 29.46 (SD=6.69), which was 61.37% of the maximum point number (Table 6). Patients obtained the highest result in the Meaning dimension, and the lowest in the Faith dimension. Patient sex had strong significant correlation with the total score and subscale scores (total score: male: M=28.04±7.25; female: M=30.36±6.16, P=0.001). Older patients with diagnosed chronic disease for a longer time received higher results in the total score and Faith subscale of the FACIT-Sp-12 (P<0.001). Education had negative correlation with the total and subscale scores (total score: primary school: M=30.05±5.91; high school: M=30.42±6.62; university: 25.9±7.09, P<0.001). Participants who declared their faith as Catholic scored higher on all 3 subscales as well as for the whole scale (total score: Catholic: M=30.19±6.11; others: M=23.78±8.22, P<0.001). The respondents who had statements of disability were statistically negatively correlated with the overall result and subscales. Regarding the type of chronic disease the respondents had, only diabetes was statistically negatively correlated with the Meaning subscale. A positive correlation was obtained between the Faith subscale and patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Table 8).

Discussion

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY:

This study has some limitations that should be considered. We used a convenience sampling method to select the study group; therefore, our study was limited by its culturally homogenous sample of patients with chronic disease who were in treatment in an eastern part of Poland, and the generalizability of the findings to a more racially and ethnically diverse Polish population is uncertain. Replication of this study across a larger sample with diverse populations from nursing homes, hospices, and those under nursing care at the place of residence would help us confirm the validity and reliability of the Polish translation of the FACIT-Sp-12. Further research is needed. Another limitation of the study is that our findings may not be generalizable across all Catholic contexts. The results of the FACIT may differ in regions of Central or South America, where Catholic culture differs. Additionally, the average age of the respondents was 58 years. We tried to recruit more respondents with chronic diseases in pre-working age; however, chronic diseases in Poland are detected too late, usually at an advanced stage, and on the occasion of another medical examination [48]. In the future, the research should also include patients covered by outpatient specialist care. Finally, the study design was cross-sectional, and the test-retest reliability – referring to the temporal stability for the same individuals on at least 2 occasions – of the FACIT-Sp-12 was therefore not assessed. Previous studies of the instrument did not retest reliability, owing to various limitations [34–36]. In our case, due to sanitary and epidemiological restrictions because of the coronavirus pandemic, it was decided to limit contact with chronically ill patients for fear of the risk of virus transmission. Future studies might concentrate on these restrictions as well as using a deeper study design by stratifying age groups or affiliations. Researchers are aware of the existence of other tools measuring the spiritual well-being of patients, including the SWBS [76] or Multidimensional Inventory for Religious/Spiritual Well-Being [77]; however, none of these tools have been validated and culturally adapted to Polish conditions. Therefore, it was impossible to compare the FACIT-Sp-12 with other tools measuring the spiritual well-being of patients with chronic illness. Researchers commit to following scientific research in the field of spirituality and spiritual well-being for comparison with tools that may be validated in the future. Despite these limitations, the present study is unique in providing a validated tool for assessing spiritual well-being in Polish-speaking patients with chronic diseases. The results provided confirmation of the reliability and relevance of the FACIT-Sp-12 and its use as a tool to assess spiritual well-being in clinical nursing practice. In addition, the study group was large and representative of Polish society, which allows us to claim that the FACIT-Sp-12 is a good tool to assess the spiritual well-being of the general Polish population with chronic diseases.

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS:

It is important to note that spirituality is a deeply personal and subjective aspect of human experience, and its impact on health-related quality of life can vary from person to person. Nonetheless, recognizing and addressing spiritual well-being as part of overall health care can lead to a more holistic approach to promoting well-being and supporting individuals in their journey toward a fulfilling life. Our study introduced the Polish version of the FACIT-Sp-12 as a valid and reliable tool for clinicians to use to assess the spiritual well-being of patients with chronic illness. The FACIT-Sp-12 helps clinicians understand the unique spiritual experiences and needs of patients, providing a comprehensive view of their overall well-being beyond physical symptoms. Understanding a patient’s spiritual beliefs, values, and resources can guide the development of interventions that incorporate and support their spiritual needs. This holistic approach can enhance patient-centered care and improve treatment outcomes.

Conclusions

The present research, which was the first study conducted in Poland to assess the spiritual well-being of patients with chronic illness, has shown that the Polish FACIT-Sp-12 is a reliable tool adapted to cultural conditions and characterized by acceptable psychometric properties for the Polish population. In a future study, it would be interesting to investigate relationship between spiritual well-being and other domains of quality of life, such as emotional well-being, physical well-being, or social well-being. The process of adaptation, validation, and testing of FACIT-Sp-12 psychometric properties provides the opportunity to fill in the gaps in the current knowledge on this subject. In the future, it provides the opportunity to assess the spiritual well-being of patients and create a plan of spiritual care corresponding to their current condition and needs.

Tables

Table 1. The Polish version of the FACIT-Sp-12.Poniższa lista obejmuje stwierdzenia, które inne osoby z tą samą chorobą uznały za istotne.Proszę zakreślić lub zaznaczyć jedną liczbę w każdym wierszu, aby wskazać odpowiedź dotyczącą ostatnich 7 dni. Table 2. Characteristic of study participants.

Table 2. Characteristic of study participants. Table 3. Items loadings in factor analysis of the FACIT-Sp-12 scale (3- or 2-factor solution).

Table 3. Items loadings in factor analysis of the FACIT-Sp-12 scale (3- or 2-factor solution). Table 4. Goodness-of-fit summary for the models tested in this study.

Table 4. Goodness-of-fit summary for the models tested in this study. Table 5. Standardized parameters for 3 factors (initial structure) model.

Table 5. Standardized parameters for 3 factors (initial structure) model. Table 6. Internal consistency of the of FACIT Sp-12.

Table 6. Internal consistency of the of FACIT Sp-12. Table 7. Spiritual well being of chronically ill patients and their religiosity.

Table 7. Spiritual well being of chronically ill patients and their religiosity. Table 8. FACIT-Sp-12 Total and Subscale subscores by sociodemographic and health variables, questions 1–4.

Table 8. FACIT-Sp-12 Total and Subscale subscores by sociodemographic and health variables, questions 1–4.

References

1. Savel RH, Munro CL, The importance of spirituality in patient-centered care: Am J Crit Care, 2014; 23(4); 276-78

2. Balboni TA, VanderWeele TJ, Doan-Soares SD, Spirituality in serious illness and health: JAMA, 2022; 328(2); 184

3. Aghaei MH, Vanaki Z, Mohammadi E, Inducing a sense of worthiness in patients: The basis of patient-centered palliative care for cancer patients in Iran: BMC Palliat Care, 2021; 20(1); 38

4. Palmer Kelly E, Hyer M, Tsilimigras D, Pawlik TM, Healthcare provider self-reported observations and behaviors regarding their role in the spiritual care of cancer patients: Support Care Cancer, 2021; 29(8); 4405-12

5. Puchalski C, Ferrell B: Making health care whole: Integrating spirituality into patient care, 2010, West Conshohocken, PA, Templeton Press

6. Ross L, McSherry W, Giske T, Nursing and midwifery students’ perceptions of spirituality, spiritual care, and spiritual care competency: A prospective, longitudinal, correlational European study: Nurse Educ Today, 2018; 67; 64-71

7. Turke KC, Canonaco JS, Artioli T, Depression, anxiety and spirituality in oncology patients: Rev Assoc Med Bras, 2020; 66(7); 960-65

8. Xing L, Guo X, Bai L, Are spiritual interventions beneficial to patients with cancer?: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials following PRISMA: Medicine, 2018; 97(35); e11948

9. Moons P, Luyckx K, Dezutter JAPPROACH-IS Consortium; International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ISACHD), Religion and spirituality as predictors of patient-reported outcomes in adults with congenital heart disease around the globe: Int J Cardiol, 2019; 274; 93-99

10. Abu HO, Ulbricht C, Ding E, Association of religiosity and spirituality with quality of life in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review: Qual Life Res, 2018; 27(11); 2777-97

11. Edmondson D, Park CL, Blank TO, Deconstructing spiritual well-being: Existential well-being and HRQOL in cancer survivors: Psycho-Oncology, 2008; 17(2); 161-69

12. Siqueira J, Fernandes NM, Moreira-Almeida A, Association between religiosity and happiness in patients with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis: Braz J Nephrol, 2019; 41(1); 22-28

13. Wade J, Hayes R, Wade J, Associations between religiosity, spirituality, and happiness among adults living with neurological illness: Geriatrics, 2018; 3(3); 35

14. McSherry W, Ross L, Heed the evidence on place of spiritual needs in health care: Nurs Stand, 2015; 29(38); 33

15. Best M, Butow P, Olver I, Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic literature review: Patient Educ Couns, 2015; 98(11); 1320-28

16. Rabitti E, Cavuto S, Iani L, The assessment of spiritual well-being in cancer patients with advanced disease: Which are its meaningful dimensions?: BMC Palliat Care, 2020; 19(1); 26

17. Ferrell BR, Handzo G, Picchi T, The urgency of spiritual care: COVID-19 and the critical need for whole-person palliation: J Pain Symptom Manage, 2020; 60(3); e7-e11

18. McSherry W, Ross L, Balthip K, Spiritual assessment in healthcare: An overview of comprehensive, sensitive approaches to spiritual assessment for use within the Interdisciplinary Healthcare Team: Spirituality in Healthcare: Perspectives for Innovative Practice, 2019, Cham, Springer International Publishing

19. Kwame A, Petrucka PM, A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: Barriers, facilitators, and the way forward: BMC Nurs, 2021; 20(1); 158

20. Lazenby M, Understanding and addressing the religious and spiritual needs of advanced cancer patients: Semin Oncol Nurs, 2018; 34(3); 274-83

21. Ghorbani M, Mohammadi E, Aghabozorgi R, Ramezani M, Spiritual care interventions in nursing: an integrative literature review: Support Care Cancer, 2021; 29(3); 1165-81

22. Siler S, Interprofessional perspectives on providing spiritual care for patients with lung cancer in outpatient settings: Oncol Nurs Forum, 2019; 46(1); 49-58

23. Trigueros Carrero JA, How should we define and classify exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?: Expert Rev Respir Med, 2013; 7(2 Suppl); 33-41

24. Alvarez JS, Goldraich LA, Nunes AH, Association between spirituality and adherence to management in outpatients with heart failure: Arq Bras Cardiol, 2016; 106(6); 491-501

25. Harrad R, Cosentino C, Keasley R, Sulla F, Spiritual care in nursing: An overview of the measures used to assess spiritual care provision and related factors amongst nurses: Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parmensis, 2019; 90(4-S); 44-55

26. McSherry W, Ross L, Attard J, Preparing undergraduate nurses and midwives for spiritual care: Some developments in European education over the last decade: J Study Spiritual, 2020; 10(1); 55-71

27. Booth L, Kaylor S, Teaching spiritual care within nursing education: A holistic approach: Holist Nurs Pract, 2018; 32(4); 177-81

28. Guo Y, Cross WM, Lam L, Association between psychological capital and spiritual care competencies of clinical nurses: A multicentre cross-sectional study: J Nurs Manag, 2021; 29(6); 1713-22

29. Blaber M, Jone J, Willis D, Spiritual care: Which is the best assessment tool for palliative settings?: Int J Palliat Nurs, 2015; 21(9); 430-38

30. Lucchetti G, Lucchetti ALG, de Bernardin Gonçalves JP, Vallada HP, Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp 12) among Brazilian psychiatric inpatients: J Relig Health, 2015; 54(1); 112-21

31. Alvarenga W, de A, Nascimento LC, Rebustini F, Evidence of validity of internal structure of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp-12) in Brazilian adolescents with chronic health conditions: Front Psychol, 2022; 13; 991771

32. Lazenby M, Khatib J, Al-Khair F, Neamat M, Psychometric properties of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp) in an Arabic-speaking, predominantly Muslim population: Arabic FACIT-Sp: Psycho-Oncology, 2013; 22(1); 220-27

33. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger MSTROBE Initiative, The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies: J Clin Epidemiol, 2008; 61(4); 344-49

34. Monod S, Lécureux E, Rochat E, Validity of the FACIT-Sp to assess spiritual well-being in elderly patients: Psychology, 2015; 06(10); 1311-22

35. Agli O, Bailly N, Ferrand C, Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp12) on French old people: J Relig Health, 2017; 56(2); 464-76

36. Damen A, Visser A, Laarhoven HWM, Validation of the FACIT-Sp-12 in a Dutch cohort of patients with advanced cancer: Psycho-Oncology, 2021; 30(11); 1930-38

37. Jafari N, Zamani A, Lazenby M, Translation and validation of the Persian version of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy – Spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp) among Muslim Iranians in treatment for cancer: Pall Supp Care, 2013; 11(1); 29-35

38. Fradelos E, Tzavella F, Koukia E, The translation, validation and cultural adaptation of Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Spiritual Well-being 12 (FACIT-Sp12) scale in Greek language: Mater Sociomed, 2016; 28(3); 229

39. Bredle JM, Salsman JM, Debb SM, Spiritual well-being as a component of health-related quality of life: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp): Religions, 2011; 2(1); 77-94

40. Dobrowolska B, Jurek K, Pilewska-Kozak AB, Validation of the Polish version of the Duke University Religion Index (PolDUREL): Pol Arch Med Wewn, 2016; 126(12); 1005-8

41. Koenig H, Parkerson GR, Meador KG, Religion index for psychiatric research: Am J Psychiatry, 1997; 154(6); 885-86

42. Wild D, Grove A, Martin MISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation, Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation: Value Health, 2005; 8(2); 94-104

43. Bonomi AE, Cella DF, Hahn EA, Multilingual translation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) quality of life measurement system: Qual Life Res, 1996; 5; 309-20

44. Webster KA, Peipert JD, Lent LF, The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: Guidance for use in research and clinical practice: Handbook of Quality of Life in Cancer, 2022; 79-104, Switzerland, Springer Nature

45. Department of Health, Chronic Diseases and Conditions [Internet]: Diseases and Conditions Available from: https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/chronic/

46. Comrey AL, Factor-analytic methods of scale development in personality and clinical psychology: J Consult Clin Psychol, 1988; 56(5); 754-61

47. Costello AB, Osborne J, Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis: Pract Assess Res Eval, 2005; 10; 1-9

48. Zimny-Zając A: Narodowy Test Zdrowia Polaków Warszawa: Ringer Axel, 2022, Polska, Springer [in Polish]

49. Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy – Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp): Ann Behav Med, 2002; 24(1); 49-58

50. Noguchi W, Ohno T, Morita S, Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual (FACIT-Sp) for Japanese patients with cancer: Support Care Cancer, 2004; 12(4); 240-45

51. Pereira F, Santos C, Adaptação cultural da Functional Assessment Of Chronic Illness Therapy – Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp): Estudo de validação em doentes oncológicos na fase final de vida: Cadernos de Saúde, 2011; 4(2); 37-45 [in Portuguse]

52. Hinton PR, McMurray I: Presenting your data with SPSS explained, 2017, Routledge

53. de Alvarenga WA, Nascimento LC, dos Santos CB, Measuring Spiritual Well-Being in Brazilian Adolescents with Chronic Illness Using the FACIT-Sp-12: Age Adaptation of the Self-Report Version, Development of the Parental-Report Version, and Validation: J Relig Health, 2019; 58(6); 2219-40

54. Ellison CW, Spiritual well-being: Conceptualization and measurement: J Psychol Theol, 1983; 11(4); 330-40

55. WHOQOL SRPB Group, A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life: Soc Sci Med, 2006; 62(6); 1486-97

56. Hungelmann J, Kenkel-Rossi E, Klassen L, Stollenwerk R, Development of the JAREL spiritual well-being scale: Classification of Nursing Diagnosis: Proceedings of the eight conference, North American Diagnosis Association, 1989; 393-98, Philadelphia, JB Lippincott

57. Daaleman TP, Frey BB, Wallace D, Studenski S, The Spirituality Index of Well-Being: Development and testing of a new measure: J Fam Pract, 2002; 51(11); 952

58. Clark CC, Hunter J, Spirituality, Spiritual Well-Being, and spiritual coping in advanced heart failure: Review of the literature: J Holist Nurs, 2019; 37(1); 56-73

59. Monod S, Brennan M, Rochat E, Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: A systematic review: J Gen Intern Med, 2011; 26(11); 1345-57

60. Austin P, Macdonald J, MacLeod R, Measuring spirituality and religiosity in clinical settings: A scoping review of available instruments: Religions, 2018; 9(3); 70

61. Pellengahr JM, Spiritual well-being instruments: A systematic review of the psychometric properties of frequently used scales: Twente: University of Twente;, 2018

62. Santana-Berlanga NDR, Porcel-Gálvez AM, Botello-Hermosa A, Barrientos-Trigo S, Instruments to measure quality of life in institutionalized older adults: Systematic review: Geriatr Nurs, 2020; 41(4); 445-62

63. Martoni AA, Varani S, Peghetti B, Spiritual well-being of Italian advanced cancer patients in the home palliative care setting: Eur J Cancer Care, 2017; 26; e12677

64. Hasegawa T, Kawai M, Kuzuya N, Spiritual Well-Being and Correlated Factors in Subjects with advanced COPD or lung cancer: Respir Care, 2017; 62(5); 544-49

65. Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Loghmani A, Spiritual well-being and quality of life of Iranian adults with type 2 diabetes: Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2014; 2014; 619028

66. Murphy PE, Canada AL, Fitchett G, An examination of the 3-factor model and structural invariance across racial/ethnic groups for the FACIT-Sp: A report from the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II): Psychooncology, 2010; 19(3); 264-72

67. Stojković S, Prlić N, Effect of faith on the acceptance of chronic disease patients: South Eastern Europe Health Sciences Journal, 2012; 2(1); 52-61

68. Riley BB, Perna R, Tate DG, Types of spiritual well-being among persons with chronic illness: Their relation to various forms of quality of life: Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1998; 79(3); 258-64

69. Marche A, Religion, health, and the care of seniors: Counselling, Psychotherapy, and Health, 2006; 2(1); 50-61

70. Damsma Bakker AA, van Leeuwen RRR, Roodbol PFP, The spirituality of children with chronic conditions: A qualitative meta-synthesis: J Pediatr Nurs, 2018; 43; e106-e13

71. Canada AL, Murphy PE, Fitchett G, A 3-factor model for the FACIT-Sp: Psycho-Oncology, 2008; 17(9); 908-16

72. Ferraro KF, Kelley-Moore JA, Religious consolation among men and women: Do health problems spur seeking?: J Sci Stud Rel, 2000; 39(2); 220-34

73. Cheawchanwattana A, Chunlertrith D, Saisunantararom W, Johns N, Does the spiritual well-being of chronic hemodialysis patients differ from that of pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients?: Religions, 2014; 6(1); 14-23

74. Bukowska G, Aktywność zawodowa osób starszych: Ryzyko ubóstwa osób starszych, 2011, Warszawa, CeDeWu [in Polish]

75. Büssing A, Franczak K, Surzykiewicz J, Frequency of spiritual/religious practices in Polish patients with chronic diseases: Validation of the Polish Version of the SpREUK-P Questionnaire: Religions, 2014; 5(2); 459-76

76. Paloutzian RF, Bufford RK, Wildman AJ, Spiritual Well-Being Scale: Mental and physical health relationships: Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare, 2012; 353-58, Oxford University Press

77. Unterrainer HF, Nelson O, Collicutt J, Fink A, The English Version of the Multidimensional Inventory for Religious/Spiritual Well-Being (MI-RSWB-E): First results from British College Students: Religions, 2012; 3(3); 588-99

Tables

Table 1. The Polish version of the FACIT-Sp-12.Poniższa lista obejmuje stwierdzenia, które inne osoby z tą samą chorobą uznały za istotne.Proszę zakreślić lub zaznaczyć jedną liczbę w każdym wierszu, aby wskazać odpowiedź dotyczącą ostatnich 7 dni.

Table 1. The Polish version of the FACIT-Sp-12.Poniższa lista obejmuje stwierdzenia, które inne osoby z tą samą chorobą uznały za istotne.Proszę zakreślić lub zaznaczyć jedną liczbę w każdym wierszu, aby wskazać odpowiedź dotyczącą ostatnich 7 dni. Table 2. Characteristic of study participants.

Table 2. Characteristic of study participants. Table 3. Items loadings in factor analysis of the FACIT-Sp-12 scale (3- or 2-factor solution).

Table 3. Items loadings in factor analysis of the FACIT-Sp-12 scale (3- or 2-factor solution). Table 4. Goodness-of-fit summary for the models tested in this study.

Table 4. Goodness-of-fit summary for the models tested in this study. Table 5. Standardized parameters for 3 factors (initial structure) model.

Table 5. Standardized parameters for 3 factors (initial structure) model. Table 6. Internal consistency of the of FACIT Sp-12.

Table 6. Internal consistency of the of FACIT Sp-12. Table 7. Spiritual well being of chronically ill patients and their religiosity.

Table 7. Spiritual well being of chronically ill patients and their religiosity. Table 8. FACIT-Sp-12 Total and Subscale subscores by sociodemographic and health variables, questions 1–4.

Table 8. FACIT-Sp-12 Total and Subscale subscores by sociodemographic and health variables, questions 1–4. In Press

15 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Impact of One-Lung Ventilation on Oxygenation and Ventilation Time in Thoracoscopic Heart Surgery: A Compar...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943089

14 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Differential DHA and EPA Levels in Women with Preterm and Term Births: A Tertiary Hospital Study in IndonesiaMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943895

15 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Evaluation of an Optimized Workflow for the Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Paroxysmal Atrial FibrillationMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943526

09 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Correlation between Thalamocortical Tract and Default Mode Network with Consciousness Levels in Hypoxic-Isc...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943802

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952