31 October 2023: Research

Evaluating Caudal Block Enhancements in Pediatric Circumcision: Do Additional Analgesics Make a Difference?

İlker CoşkunDOI: 10.12659/MSM.942557

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e942557

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Caudal block is widely regarded as the top choice for multimodal analgesia in children undergoing urological surgeries, particularly circumcision. This study investigates the efficacy of caudal block and the necessity of rescue analgesia in circumcision surgeries.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: A prospective, single-blind study was conducted at Ordu University Training and Research Hospital from December 1, 2022, to July 1, 2023. The study randomly divided ASA class I-II children aged 1-12 years into 3 groups for circumcision surgery. Group C received only caudal block. Group CP received caudal block with 10 mg/kg intravenous paracetamol. Group CM received caudal block with 1 mg/kg intravenous meperidine. In each case, a caudal block was administered using 0.5 ml/kg of 0.125% bupivacaine under ultrasound guidance. The primary outcome of the study was total analgesic consumption; the secondary outcomes were pain scores and time to first analgesic administration. Pain severity was evaluated using FLACC and Wong-Baker scores at 0, 1, 4, and 24 h.

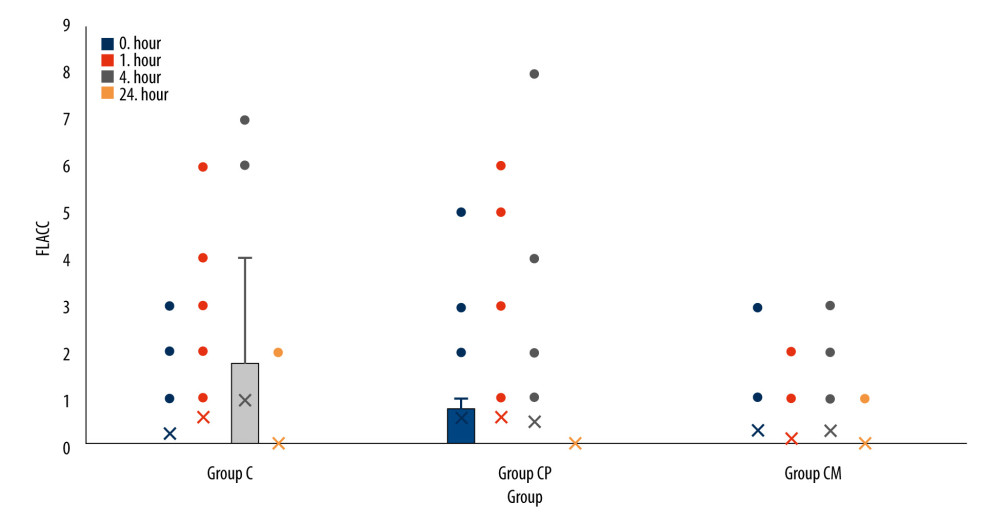

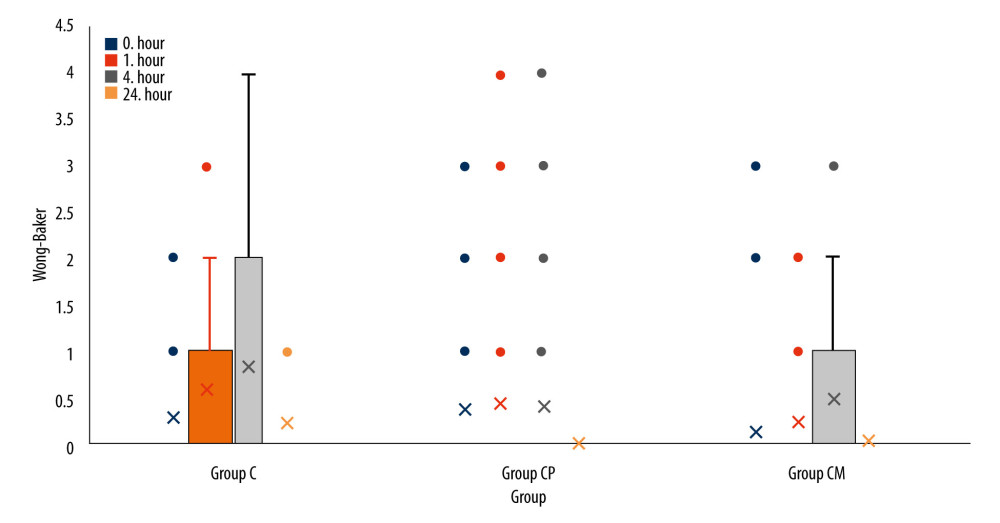

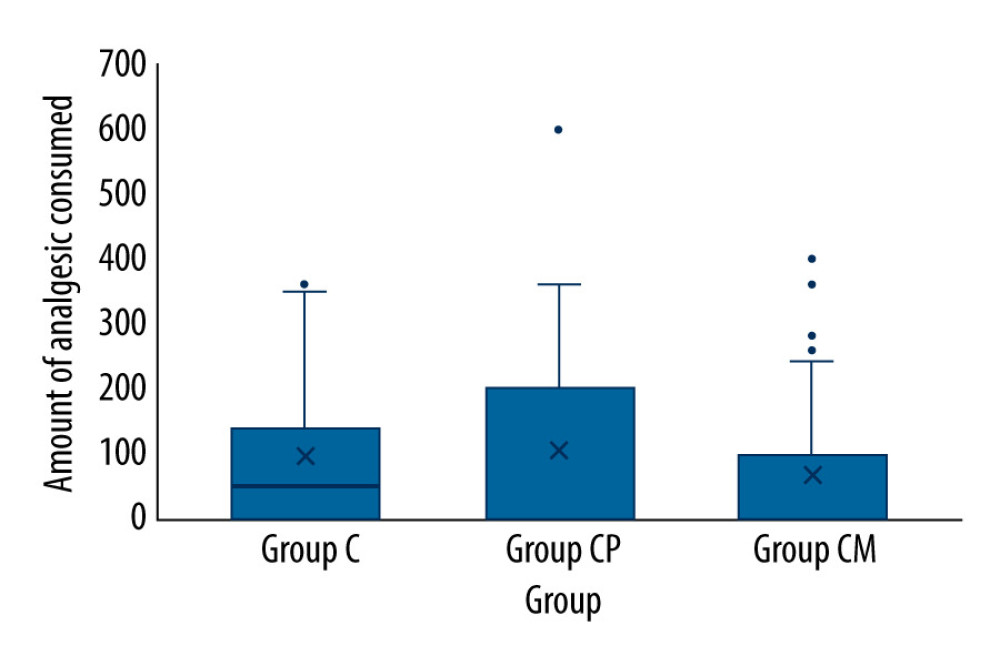

RESULTS: A total of 120 patients, 40 patients in each group, were included in the study. A significant difference was detected among all 3 groups in the Wong-Baker pain score (24th hour) (P<0.001). The FLACC and Wong-Baker pain scores did not differ significantly in the other time frames. The time of the first rescue analgesia and the total amount of analgesic taken in the first 24 h were the same for both groups (P=0.408 and P=0.238).

CONCLUSIONS: The addition of paracetamol or meperidine to caudal block does not enhance the quality of analgesia.

Keywords: Anesthesia, Caudal, pain management, Circumcision, Male

Background

Circumcision involves exposing the tip of the penis by surgically cutting away the foreskin, called the prepuce, which covers the glans [1]. The most widely performed operation in the world is circumcision, which is also the oldest surgery in the world when you consider its progression over time [2]. Pain during surgical procedures in children causes many physiological, local, and/or systemic adverse effects [3]. These effects may lead to delays in recovery, increased consumption of narcotic analgesics and associated complications, prolongation of hospital stays, and chronic pain [4].

Opioids used for postoperative analgesia in children have adverse effects such as superficial respiration and decreased intestinal motility, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and addictive behavior [5]. Because it has been used for so long in children, caudal block is regarded as the best multimodal analgesic for patients in this age range [6]. Caudal block is an effective method for postoperative analgesia in anorectal surgery, intraluminal surgery, and perineal surgery (eg, circumcision). Caudal block also reduces the use of analgesics without causing a motor block, which allows rapid mobilization of patients and reduces the incidence of postoperative adverse effects [7]. As it provides visceral analgesia, a caudal block is still the preferred method of analgesia in the pediatric age group [8–10].

The primary aim of this study was to compare the effects of caudal block alone vs with the addition of paracetamol or meperidine to caudal block on postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing circumcision surgery.

Material and Methods

ETHICS APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT:

Ethics approval for the research was obtained from the Ordu University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Decision No. 2022/223, Date: 04.11.2022) to ensure strict compliance with the principles delineated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Consent was obtained from the families of the children who would undergo circumcision surgery.

STUDY DESIGN AND SETTING:

This study was designed as a prospective, randomized, comparative investigation with blinded assessors. It was conducted at Ordu University Training and Research Hospital from December 1, 2022, to July 1, 2023.

CRITERIA FOR INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION:

Inclusion criteria were American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) class I–II, patients aged 1–12 years, undergoing circumcision surgery, and patients with family consent. Exclusion criteria were patients without family consent, patients in whom regional anesthesia was contraindicated, patients with local infection at the injection site, degenerative neuropathy, coagulopathy, brain tumors, increased intracranial pressure, anatomical difficulties, mental retardation, and patients with a history of allergy to local anesthetics, chronic pain, and severe pulmonary, renal, and hepatic dysfunction.

THE DATA ACQUISITION PROTOCOL:

Circumcision surgery was performed in the operating room of the Department of Pediatric Surgery, Ordu University Training and Research Hospital. An experienced anesthetist performed a caudal block under ultrasound (US) guidance. The same anesthetist collected data in the operating room (intraoperative) and recovery room (0th hour). The anesthetist knew which group the patient belonged to. However, the pediatric surgeon who collected data in the postoperative service (hours 1 and 4) and outpatient clinic (hour 24) did not know which group the patient belonged to.

RANDOMIZATION:

In this study, complete randomization was applied, and the sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelope (SNOSE) method was used as randomization technique. We employed the sealed envelope method to achieve randomization, guaranteeing unbiased allocation of participants to the study groups. To uphold the study’s integrity, a single-blind protocol was implemented. The anesthesiologist (EC) responsible for administering the blocks remained separate from the subsequent postoperative data collection. A different anesthesiologist (IC), unaware of the specific block performed, conducted the data collection, ensuring the blinded nature of the assessment.

ANESTHESIA MANAGEMENT:

Each patient who was accompanied to the operating room by their parents was asked if they had fasted for at least 6 h before surgery. Children who were premedicated with 0.07 mg/kg midazolam and 1 mcg/kg fentanyl were taken to the operating room. After standard monitoring, mask induction with sevoflurane was performed. The caudal block was performed under mask anesthesia. Mask anesthesia was maintained until the surgical incision. When the patient regained spontaneous breathing, mask anesthesia was discontinued and free oxygen was started. Intraoperative adverse effects such as tachycardia, bradycardia, desaturation, nausea, and vomiting were recorded. Patients were taken to the recovery room after surgery.

CAUDAL BLOCK PERFORMING:

A patient was placed in a lateral decubitus position and skin antisepsis was performed. A linear US probe (GE Logiq-e Nextgen model, General Electric Medical Systems, Phoenix, AZ, United States) (7–12 mHz) was used. The probe was first placed transversely (out of plane-short axis) over the sacral cornu in the midline. Sacral cornu, sacrococcygeal ligament, and sacral bone were examined, and anatomical structures were checked. Caudal block was not applied to patients with anomalies in caudal structures. The probe was then rotated 90 degrees and placed longitudinally (in plane-long axis), and the anatomical structures were re-examined. While the probe was in the long axis, the sacrococcygeal membrane was punctured with a 22 G-50 mm US visible nerve block needle (Echoplex, Vygon, Ecouen, France), and the sacral canal was located. Meanwhile, the visibility of the needle was monitored by US. After confirming the absence of cerebrospinal fluid or blood by negative aspiration, 0.5 ml/kg, 0.125% bupivacaine was administered. During the injection of the local anesthetic solution, expansion of the caudal epidural space or turbulent flow was observed by Doppler imaging.

PERIOPERATIVE ANALGESIA PLAN:

Group C cases received only caudal block without any other analgesic intervention. Group CP cases received 10 mg/kg intravenous paracetamol after caudal block, while group CM cases received 1 mg/kg intravenous meperidine after caudal block. In the postoperative period, if pain scores were 4 or higher, 10 mg/kg oral paracetamol syrup was administered as rescue analgesia.

OUTCOME MEASUREMENTS:

The primary outcome of the study was total analgesic consumption; the secondary outcomes were pain scores and time to first analgesic administration. Pain intensity was assessed by the FLACC (face, legs, activity, crying, and consolability) and Wong-Baker scores. They were used together in this study to ensure concurrent validity. The score calculated from 5 different categories determines the severity of pain for FLACC. The Wong-Baker pain score uses a visual scale and uses the patient’s facial expressions to assess pain. Pain scores, time of first analgesic administration (hours), total amount of analgesic administered (mg, 24 h), and adverse effects (nausea/vomiting, pruritus, and motor blockade) were monitored postoperatively in all patients. Postoperative pain monitoring was performed by the pediatric surgeon. Pain scores were assessed at 0, 1, 4, and 24 h. Thus, information on analgesic use and pain scores was gathered at 4 different times.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS v23. Agreement with the normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables by group. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the parameters, and the Duncan test or Dunn’s test was used in post hoc evaluations. The results of the analysis were presented as the mean±SD for quantitative data. Categorical data (variance and median minimum-maximum) were presented as frequency (percentage). The significance level was set as

POWER ANALYSIS:

The sample size determination for this study relied on opioid consumption data obtained from a previous study [11]. Calculations were performed using the G*Power V. 3.1.9.6 software. A total of 90 cases, distributed evenly with 30 cases in each group, were determined to be necessary for this study, considering a 95% confidence level (1−α), a 90% test power (1−β), and an effect size of d=1.02. Considering the potential for dropouts and data loss, the study aimed to enroll 41 patients in each group as part of the planned sample size.

Results

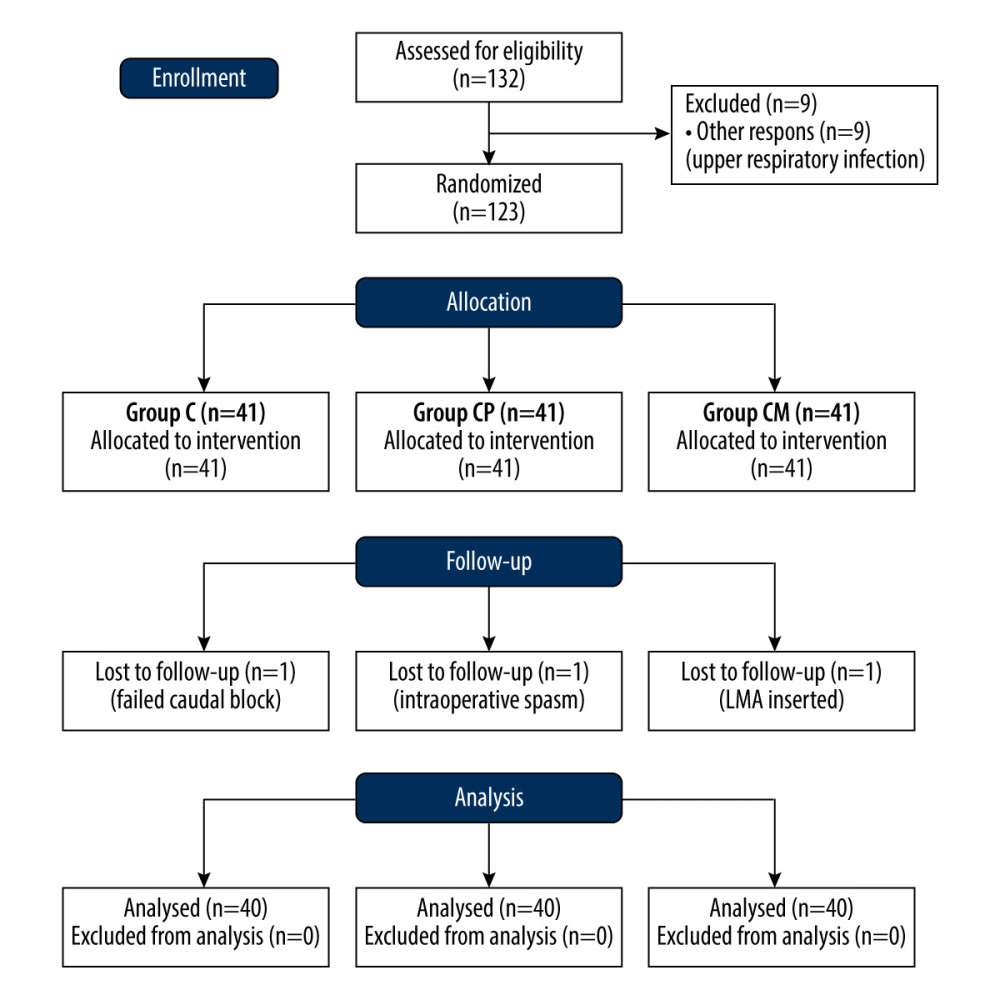

Of the 132 patients planned to be included in the study, 9 were not taken into surgery due to an upper-respiratory tract infection. A total of 123 patients were randomly divided into 3 groups: 41 were in Group C, 41 in Group CP, and 41 in Group CM. However, a total of 3 patients, 1 from each group, were excluded from the study for different reasons. Therefore, 40 patients were analyzed for each group. Figure 1 displays as the CONSORT diagram and delineates the enrollment process for this study.

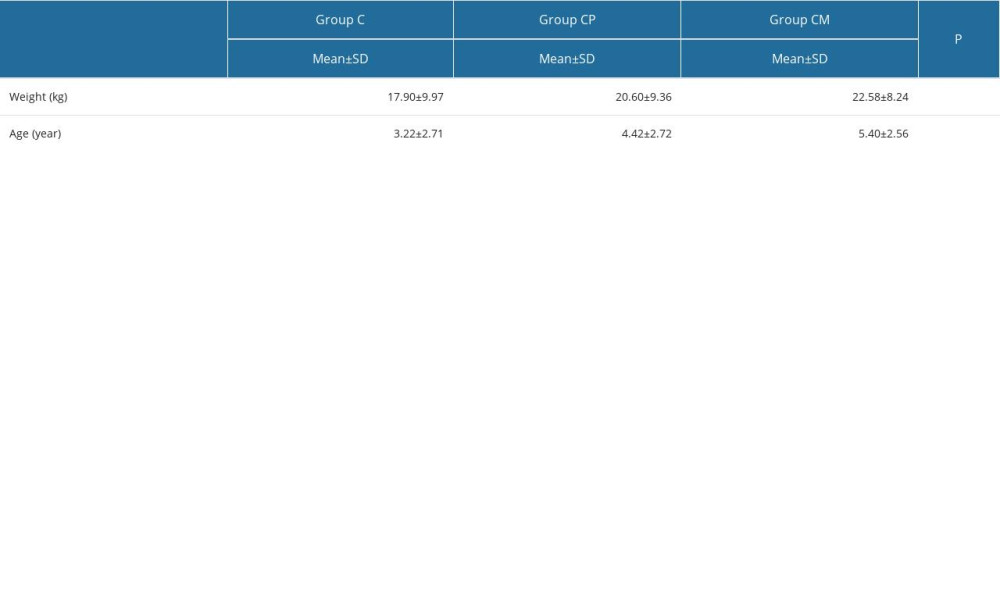

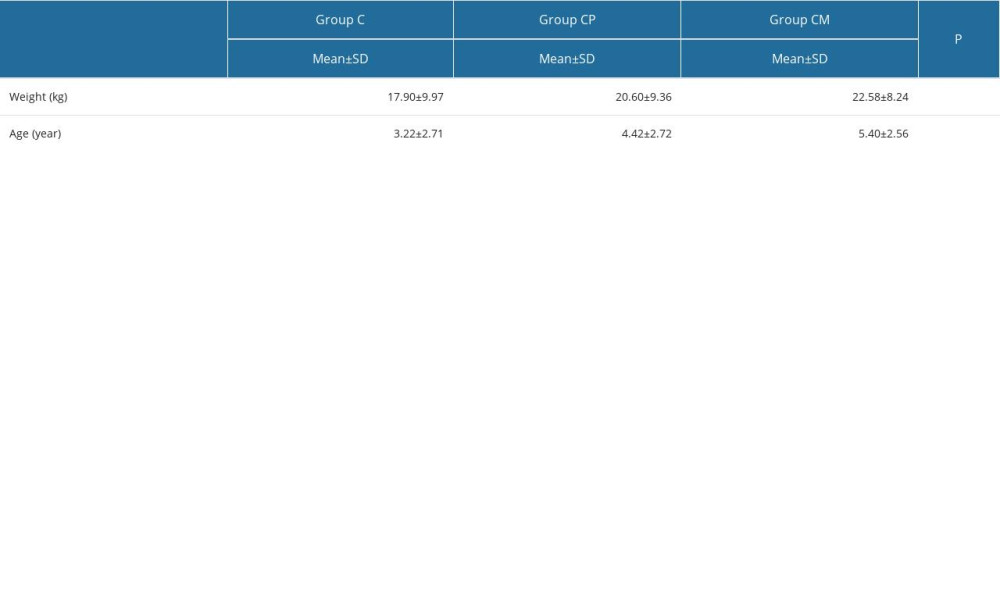

Significant results were obtained when the group weight and age variables were analyzed. The results are presented in Table 1 (

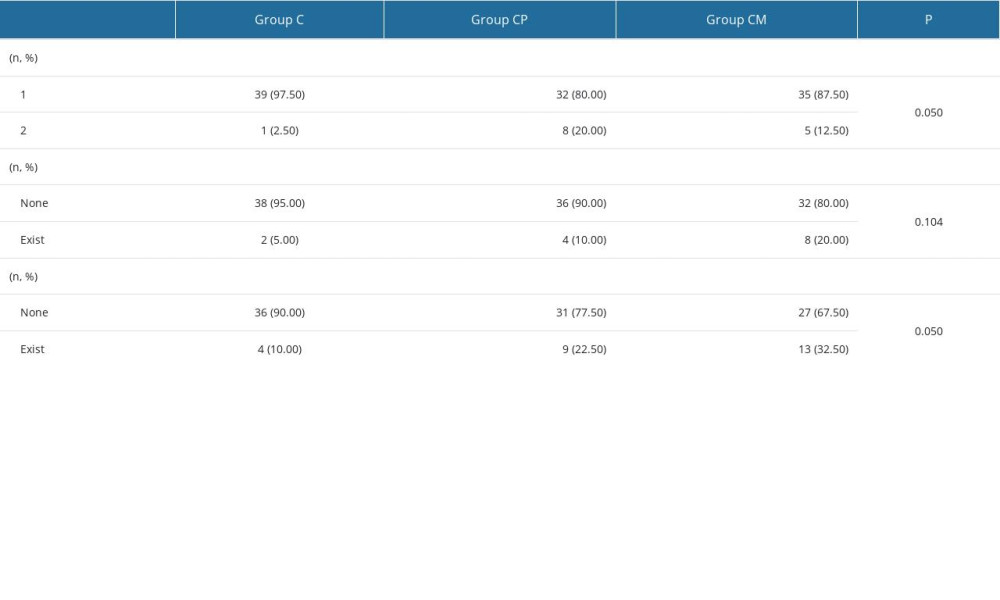

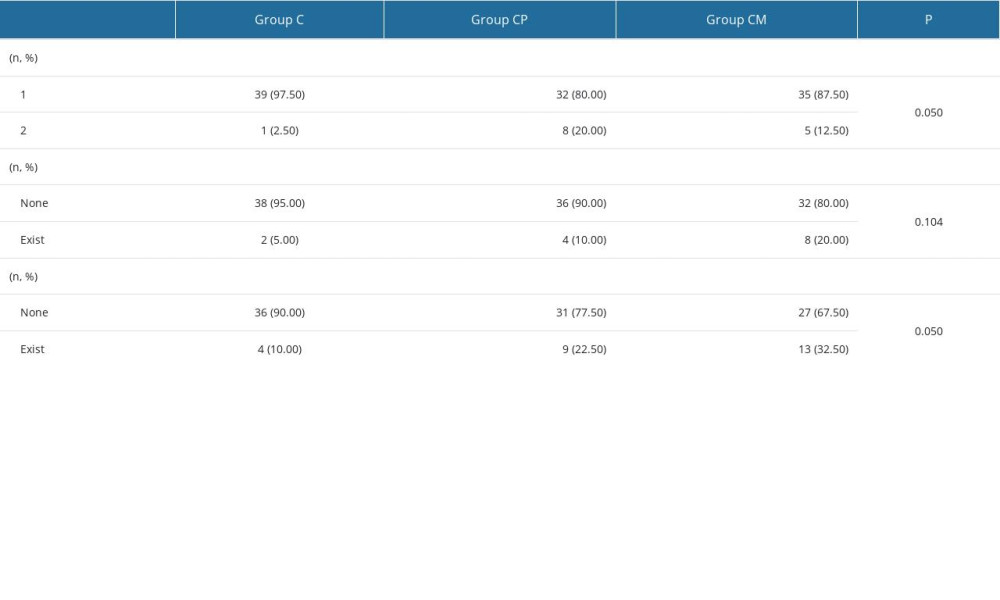

There were no significant differences observed between the groups in the ASA class (

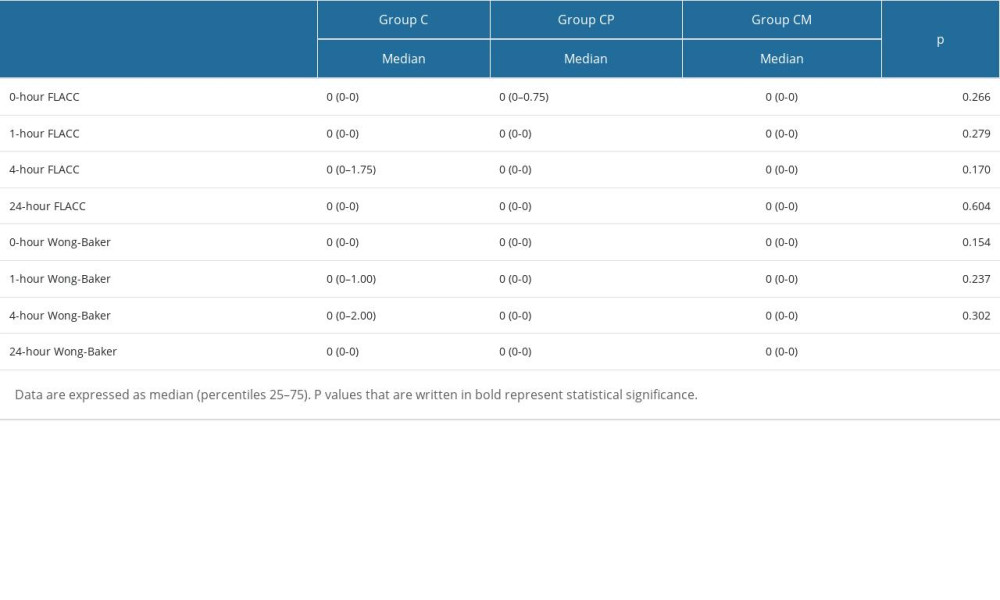

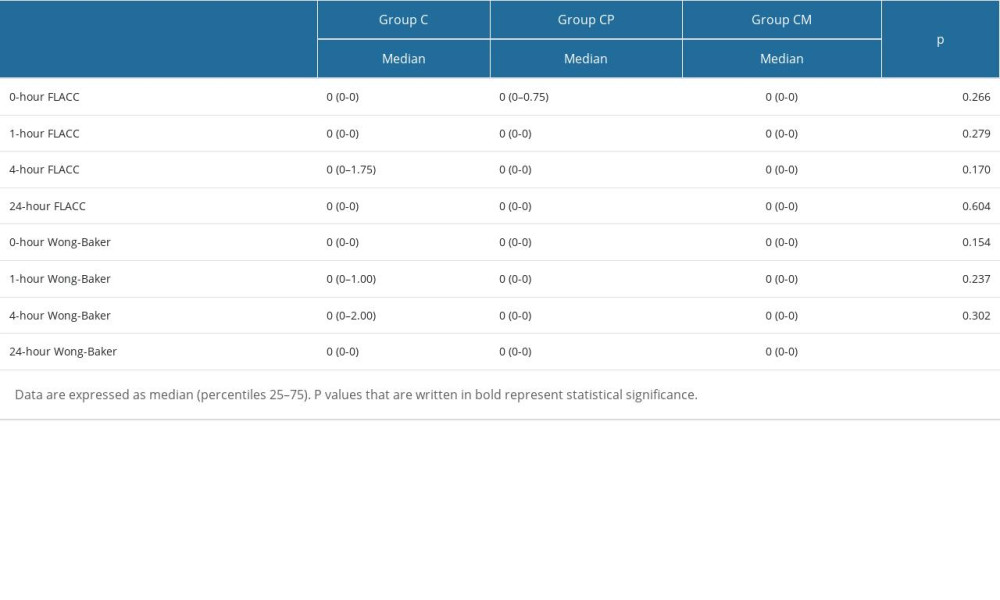

Among the time periods measured according to the groups, only the 24th h Wong-Baker pain scores were significantly different (

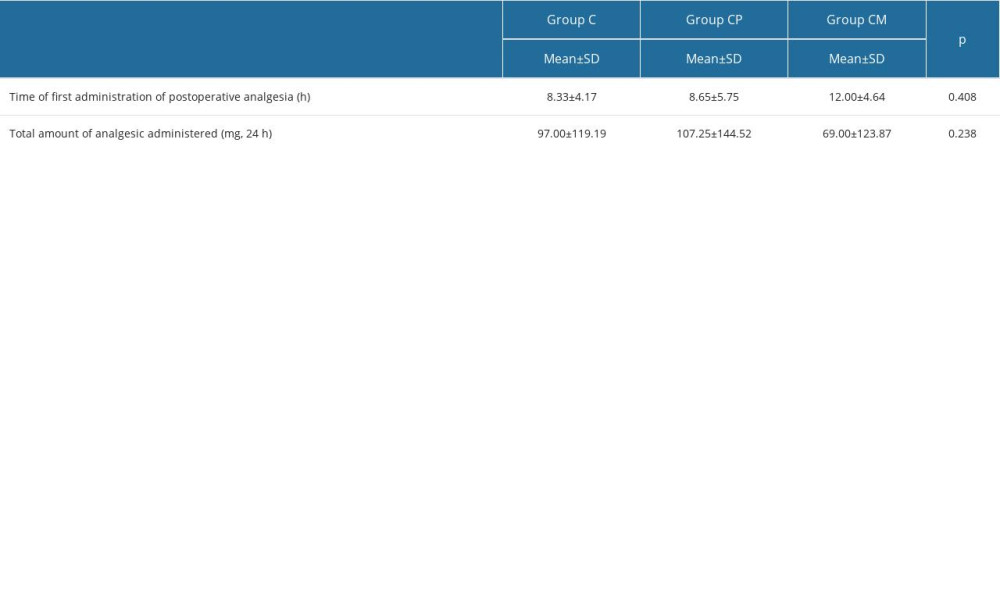

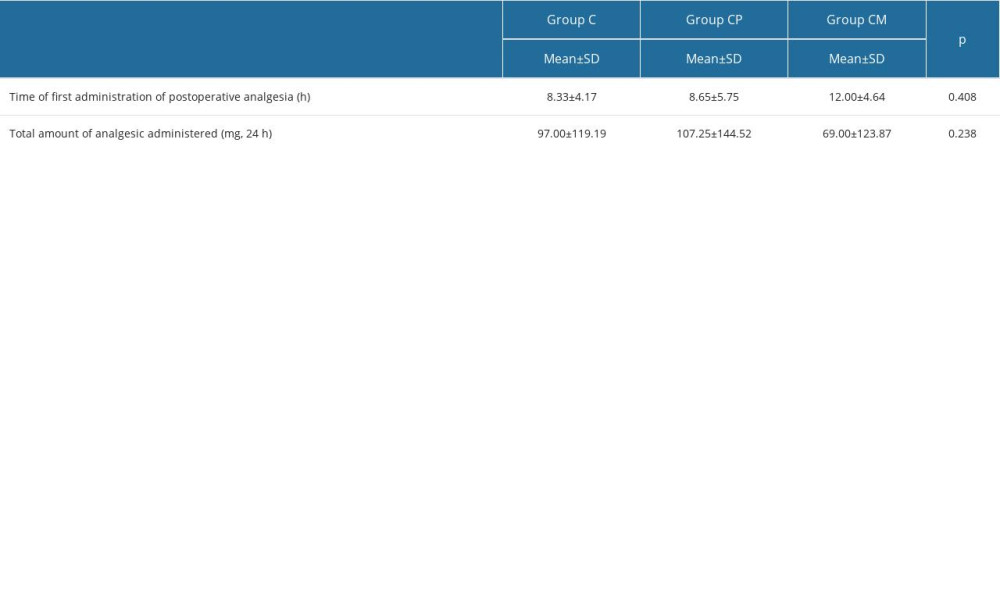

There was no difference between the postoperative hours in which analgesics were administered and the total amount of analgesics (rescue analgesic 10 mg/kg oral paracetamol) by groups (

Discussion

LIMITATIONS:

Our study has some limitations. First, the cases could not be categorized in terms of age group. Perhaps it may be more useful to categorize ages (eg, 0–3 years, 3–6 years, 6–9 years) in similar studies to be conducted in the future. The second limiting factor is that we evaluated pain scores only in the first 24 h postoperatively.

Conclusions

The addition of intravenous paracetamol or intravenous meperidine to a single caudal block was not superior to a caudal block alone in terms of analgesic requirement or total analgesic consumption and did not contribute to the quality of analgesia. Caudal block may be preferred for postoperative analgesia in circumcision surgery.

References

1. Hayashi Y, Kojima Y, Mizuno K, Kohri K, Prepuce: Phimosis, paraphimosis, and circumcision: ScientificWorldJournal, 2011; 11; 289-301

2. Tobian AA, Gray RH, The medical benefits of male circumcision: JAMA, 2011; 306(13); 1479-80

3. Macres SM, Moore PG, Fishman SM, Acute pain management: Clinical anesthesia, 2013; 1611-42, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

4. Wen SQ, Taylor BJ, Lixia Z, Hong-Gu H, Children’s experiences of their postoperative pain management: A qualitative systematic review: JBI Evidence Synthesis, 2013; 11(4); 1-66

5. Hurley RW, Wu CL, Acute postoperative pain: Miller’s anesthesia, 2010; 2757-87, Philadelphia, Churchill Livingston Elsevier

6. Shah UJ, Karuppiah N, Karapetyan H, Analgesic efficacy of adjuvant medications in the pediatric caudal block for infraumbilical surgery: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: Cureus, 2022; 14(8); e28582

7. Brasher C, Gafsous B, Dugue S, Postoperative pain Management in children and infants: An update: Pediatr Drugs, 2014; 16; 129-40

8. Kao S-C, Lin C-S, Caudal epidural block: An updated review of anatomy and techniques: Biomed Res Int, 2017; 2017; 9217145

9. Faasse MA, Lindgren BW, Frainey BT, Perioperative effects of caudal and transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks for children under going urologic robot assisted laparoscopic surgery: J Pediatr Urol, 2015; 11(3); 121

10. Sethi N, Pant D, Dutta A, Comparison of caudale pidural block and ultrasonography-guided transversus abdominis plane block for pain relief in children under going lower abdominal surgery: J Clin Anesth, 2016; 33; 322-29

11. Sahin L, Soydinc MH, Sen E, Comparison of 3 different regional block techniques in pediatric patients. A prospective randomized single-blinded study: Saudi Med J, 2017; 38(9); 952-59

12. Chou R, Gordon DB, Leon-Casasola OA, Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council: J Pain, 2016; 17(2); 131

13. Osmani F, Ferrer F, Barnet RB, Regional anesthesia for ambulatory pediatric penoscrotal procedures: J Pediatr Urol, 2021; 17(6); 836-44

14. Karkera MM, Harrison DR, Aunspaugh JP, Martin TW, Assessing caudal block concentrations of bupivacaine with and without the addition of intravenous fentanyl on postoperative outcomes in pediatric patients: Am J Ther, 2016; 23(3); e792-98

15. Bilgen S, Koner O, Menda F, A comparison of two different doses of bupivacaine in caudal anesthesia for neonatal circumcision. A randomized clinical trial: Middle East J Anaesthesiol, 2013; 22(1); 93-98

16. Kollipara N, Kodali VRK, Parameswari A, A randomized double-blinded controlled trial comparing ultrasound-guided versus conventional injection for caudal block in children undergoing infra-umbilical surgeries: J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol, 2021; 37(2); 249-54

17. Ahiskalioglu A, Yayik AM, Ahiskalioglu OE, Ultrasound-guided versus conventional injection for caudal block in children: A prospective randomized clinical study: J Clin Anesth, 2018; 44(1); 91-96

18. Wiegele M, Marhofer P, Lonnqvist PA, Caudal epidural blocks in paediatric patients: A review and practical considerations: Br J Anaesth, 2019; 122(4); 509-17

19. Margetts L, Carr B, McFadyen G, Lambert B, A comparison of caudal bupivacaine and ketamine with penile block for paediatric circumcision: Eur J Anaesthesiol, 2008; 25(12); 1009-13

20. Haque MM, Banik D, Ahtarüzzaman AK, Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to bupivacaine in caudal analgesia in children undergoing infra-umbilical surgery mymensingh: Med J, 2023; 32(3); 833-40

21. Dostbil A, Çelik MG, Aksoy M, The effects of different doses of caudal morphine with levobupivacaine on postoperative vomiting and quality of analgesia after circumcision: Anaesth Intensive Care, 2014; 42(2); 234-38

22. Münevveroğlu Ç, Gündüz M, Postoperative pain management for circumcision; Comparison of frequently used methods: Pak J Med Sci, 2020; 36(2); 91-95

23. Cyna AM, Middleton P, Caudal epidural block versus other methods of postoperative pain relief for circumcision in boys: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2008; 2008(4); CD003005

24. Bogaert GA, Trouet D, Bernaerts J, Additional to caudal bupivacaine preemptive oral ibuprofen does not improve postoperative pain, nausea or vomiting, and resumption of normal activities in children after ambulatory pediatric urologic surgery: J Pediatr Urol, 2005; 1(2); 61-68

25. Chan KH, Shah A, Moser EA, Comparison of intraoperative and early postoperative outcomes of caudal vs dorsal penile nerve blocks for outpatient penile surgeries: Urology, 2018; 118; 164-71

26. Canakci E, Yagan O, Tas N, Comparison of preventive analgesia techniques in circumcision cases: Dorsal penile nerve block, caudal block, or subcutaneous morphine: JPMA, 2017; 67(2); 159-65

27. Haliloğlu AH, Gökçe Mİ, Tangal S, Comparison of postoperative analgesic efficacy of penile block, caudal block and intravenous paracetamol for circumcision: A prospective randomized study: Int Braz J Urol, 2013; 39(4); 551-57

28. Zavras N, Tsamoudaki S, Christianakis E, Ring block with levobupivacaine 0.25% and paracetamol vs. paracetamol alone in children submitted to three different surgical techniques of circumcision: A prospective randomized study: Saudi J Anaesth, 2014; 8(1); 45-50

29. Weksler N, Atias I, Klein M, Is penile block better than caudal epidural block for post circumcision analgesia?: J Anesth, 2005; 19(1); 36-69

Figures

Tables

Table 1. Comparisons of weight and age by group.

Table 1. Comparisons of weight and age by group. Table 2. Comparison of categorical variables by group.

Table 2. Comparison of categorical variables by group. Table 3. Comparison of FLACC and Wong-Baker scores by groups.

Table 3. Comparison of FLACC and Wong-Baker scores by groups. Table 4. Comparison of analgesic variables in each group.

Table 4. Comparison of analgesic variables in each group. Table 1. Comparisons of weight and age by group.

Table 1. Comparisons of weight and age by group. Table 2. Comparison of categorical variables by group.

Table 2. Comparison of categorical variables by group. Table 3. Comparison of FLACC and Wong-Baker scores by groups.

Table 3. Comparison of FLACC and Wong-Baker scores by groups. Table 4. Comparison of analgesic variables in each group.

Table 4. Comparison of analgesic variables in each group. In Press

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952