04 February 2024: Database Analysis

Factors Influencing Dentists’ Choice of Restorative Materials for Single-Tooth Crowns: A Survey Among Saudi Practitioners

Ali Robaian1ABEFG*, Nawaf Munawir Alotaibi2BFG, Aljowhara Khaled Allaboon3BG, Dana Saleh AlTuwaijri4BDG, Abdullah Fahad Aljarallah5ABFG, Rola Salman Alshehri6BC, Aljawharah Ali Alabsi7BG, Mubashir Baig MirzaDOI: 10.12659/MSM.942723

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942723

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Material selection is crucial in restorative dentistry, influenced by aesthetics, material properties, and tooth location. This understanding is key for advancing dental practices and patient outcomes. The present study aimed to assess dentists’ preferences for restorative materials in single-tooth crowns (SC) and how abutment tooth location and preparation margins influence these choices.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: A web-based pre-validated questionnaire survey was conducted among 811 actively practicing dentists in Saudi Arabia.

RESULTS: In posterior teeth, we found that ceramic was the most preferred material for SC regardless of the abutment tooth location and location of margins, followed by porcelain fused to metal (PFMs). In anterior teeth, ceramics were preferred, followed by CAD/CAM-based resin SC. Among the choice of ceramics in teeth for both supra-gingival margins, monolith zirconia was the most-preferred material for SC fabrication in posterior teeth, followed by zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramic. Similarly, for sub-gingival margins, monolith zirconia crowns were the most popular option in posterior teeth among the respondents, with the highest in the mandibular molar region. In the anterior region, layered zirconia was the least preferred, and lithium disilicate ceramics was the most-favored option. A statistically significant difference existed between supra- and subgingival preparation for teeth 11 (P=0.01), 16 (P=0.03), and 34 (P=0.02).

CONCLUSIONS: Ceramic was the material of choice among Saudi dentists for replacement of SC, irrespective of the location and preparation margin. Monolith zirconia was usually selected for posterior teeth and lithium disilicate ceramics was the top choice in anterior teeth.

Keywords: Ceramics, Dentists, Zirconium Oxide

Background

Dentist now have a variety of options for restoring teeth with single crowns (SC), with several new materials being introduced and/or continuous evolution of existing materials. These materials are metal, metal-ceramic restorations, all-ceramic restorations, and resin-based restorations, and the choice among them is usually based on esthetics, strength, durability, biocompatibility, and cost-effectiveness [1]. Increased esthetic demand led to a decline in the use of full-metal crowns, which were previously the material of choice for fabricating full crowns. Feldspathic porcelain was the first ceramic material developed with high translucency, but it had low flexural strength and was inherently brittle [2]. Consequently, the fusing of feldspathic porcelain to metal (PFM) was introduced to strengthen the restoration. Although hugely popular, chipping of ceramics and grey shimmering were its shortcomings [3]. The discovery of leucite and the fabrication of high-strength glass ceramics led to the development of leucite-based and lithium disilicate-based glass ceramics, while glass-infiltrated ceramics consist of 3 systems that include zirconia as one of the systems [4].

More recently, the use of CAD/CAM for fabrication of prostheses has gained popularity [5]. Such prostheses are associated with good adaptation to biological tissues, excellent color stability, and superior physical and chemical endurance [6,7]. CAD/CAM-based zirconia crowns gained preference due to their strong resistance to occlusal forces and wear resemblance similar to natural teeth [8]. However, these materials exhibited a crucial disadvantage, which was high susceptibility to tensile fracture [9]. Zirconia-reformed lithium silicate (ZLS) is a new-generation high-strength CAD/CAM ceramic introduced since 2012, which has more resistant to fracture, easier milling, and easy chairside polishing [10,11]. These newer types of zirconia materials are more translucent due to its increased optically isotropic cubic phase, which expands its use in the anterior region [5].

Lithium disilicates are more translucent than zirconia and are commonly chosen for restoring the anterior region [12,13]. However, their use in the posterior region is fairly limited, as they exhibit only about 40% strength and 57% fracture resistance when used in the posterior region [8,14]. Lately, leucite-reinforced glass ceramics have been proven to be more transparent than lithium disilicate and are recommended in the anterior region [15]. CAD/CAM resin crowns fabricated through resin-based ceramics ingots have recently emerged. The most notable advantages of these materials are their good retention, easy intraoral repair with light-cured restoratives, and a faster production rate since firing is not needed [16], but their use is mostly limited to indirect restorations like inlay, onlay, and SC.

With the availability of such a large range of materials, there have been wide variations in dentists’ preferences worldwide. Similar cross-sectional surveys among American and German dentists are found in the literature, suggesting the choice of material is influenced by individual characteristics of the participating dentists and clinical scenarios [17]. Except for a study on indirect restoration [18], there is no available information related to dentists in Saudi Arabia regarding their preferred material and variations if any, based on the location of the abutment tooth and position of preparation margins.

Thus, this study aimed to assess the preferences of dentists regarding the materials used for single-tooth crowns and the existing variations based on preparation margins, tooth location, age, gender, and area of expertise. The null hypothesis of this present study was that dentists’ preferences for restorative materials for SC in Saudi Arabia did not significantly differ based on the abutment tooth’s location and the type of preparation margin.

Material and Methods

STUDY DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS:

Institutional ethics committee approval was obtained from the Standing committee for bioethics research (proposal no: SCBR-072-2023). This study was a cross-sectional web-based survey formulated using Google Forms, based on a pre-validated questionnaire, aimed to identify the preferred material for SC among dentists in Saudi Arabia from May 2023 to August 2023 [17]. The questionnaire was reviewed by a team of dentists with clinical experience, prosthodontists, and statisticians. Based on their recommendations, necessary modifications were made to suit the study objectives based on local context. The survey link was sent to practicing Saudi dentists via Twitter, WhatsApp, Telegram, and email. The anonymity of the participants was maintained as no personal identifiers were enquired. The contact details (email ID) of registered dentists were obtained from the database of the Saudi Dental Society. Information on the title and purpose of the study was provided. Participation in and completion of the survey was considered as informed consent.

SAMPLE SIZE:

Sample size calculation was done using the formula

where Zα=1.96 at 95% confidence level; N=sample size; p=proportion; q=1-p; d=relative precision.

With 95% confidence level and 90% power by assuming 50% prevalence, a minimal sample size of 385 was required. A total of 811 male and female participants from 5 different regions (east, west, north, south, and central) of Saudi Arabia took part in this survey.

VARIABLES:

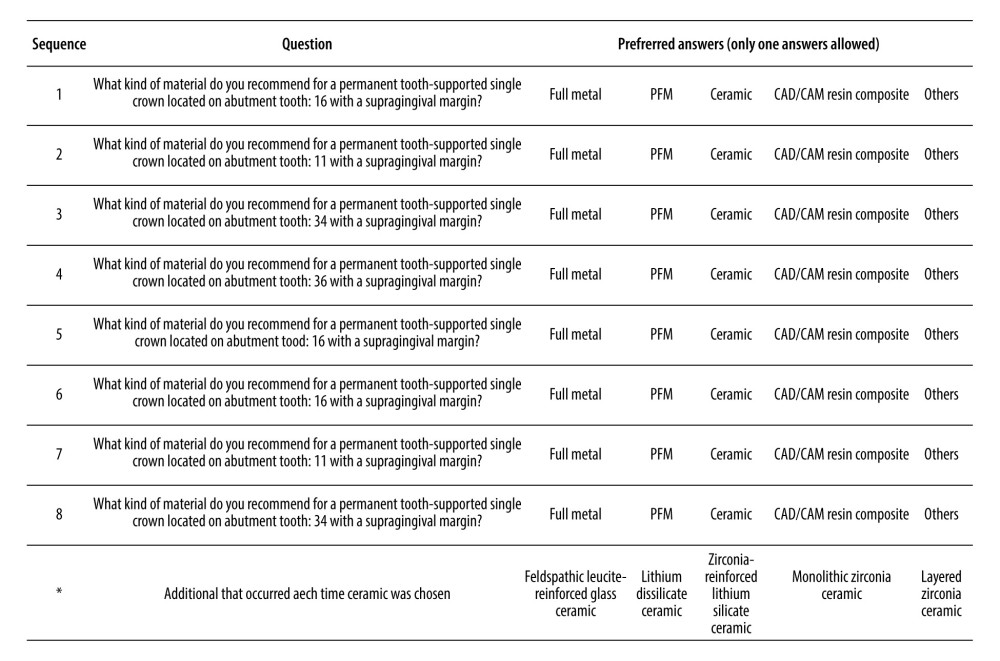

Figure 1 shows the structure of the questionnaire used for investigating the preferred materials in fabricating single crowns among dentists. The options included all the varieties of crown materials, and only 1 answer was allowed for each question. The questionnaire consisted of 2 parts. The first part included questions related to demographic characteristics of the subjects such as age, gender, years since graduation, area of expertise, and location of practice. The second part contained questions that assessed the preference of restorative materials for SC. To identify the choice of materials by the participants, the second section of the questionnaire contained 4 different locations of abutment tooth, (namely numbers 16, 11, 34, and 36 as per the FDI tooth numbering system), as well as different margins of preparation (supragingival and subgingival) for each abutment tooth under consideration.

There were 8 questions in the second portion of the questionnaire. Each question was framed in the following pattern: “What kind of material do you usually recommend for a permanent tooth-supported SC located on abutment tooth (A) and with a (B) preparation margin?” Options like metal, PFM, ceramics, CAD/CAM resin composite, and any other were provided for each question. If ceramic was selected as the preferred material of choice, then the participant had to answer an additional question regarding the preferred ceramic materials, which included the following options: feldspathic/leucite-reinforced glass ceramic, lithium disilicate ceramic, zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramic, monolithic zirconia ceramic, and layered zirconia ceramic.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 28.0 (SPSS 28, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data were used to analyze the frequencies and percentages of participant responses. Comparison of preferences based on age, gender, area of expertise, years of experience, and location of practice was made using the chi-square test. A

Results

DEMOGRAPHIC DETAILS OF THE STUDY POPULATION:

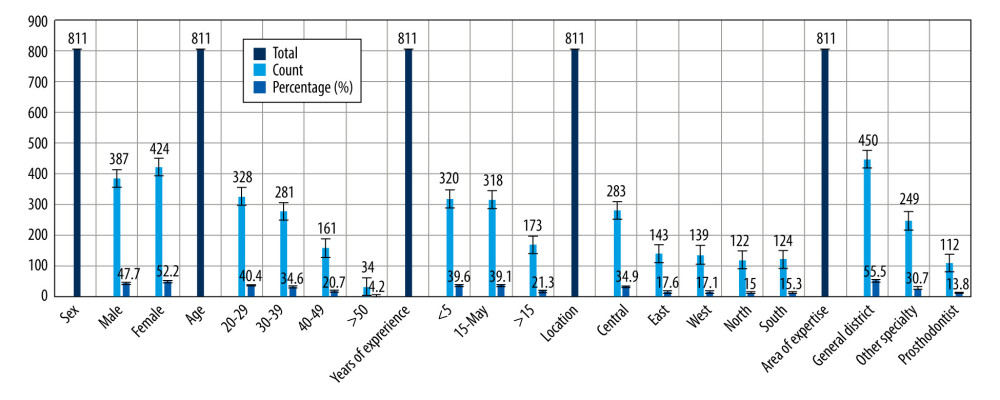

A total of 811 dentists participated in the study. Out of these, 450 were general dentists, 112 were prosthodontists, and 249 were dentists from other specialties. There were slightly more female respondents (52.3%) than males (47.7%). Among the participants, two-fifths were age 20–29 years, and just over a one-third were 30–39 years, while the remaining were 40 years old and above. About 40% of the dentists had graduated less than 5 years ago, another 40% had graduated 5–15 years ago, and 21.3% had graduated 15 or more years ago. Regarding the location, around 35% of the dentists practiced in the central zone, 17.6% were from the east zone, 17.1% were from the west zone, 15% were from the north zone, and 15.3% were from the south zone of Saudi Arabia (Figure 2).

INFLUENCE OF DENTISTS’ CHARACTERISTICS ON MATERIAL CHOICE:

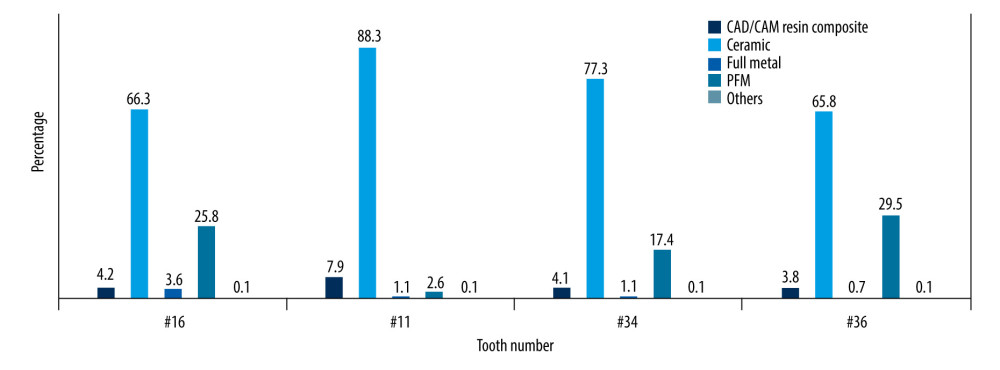

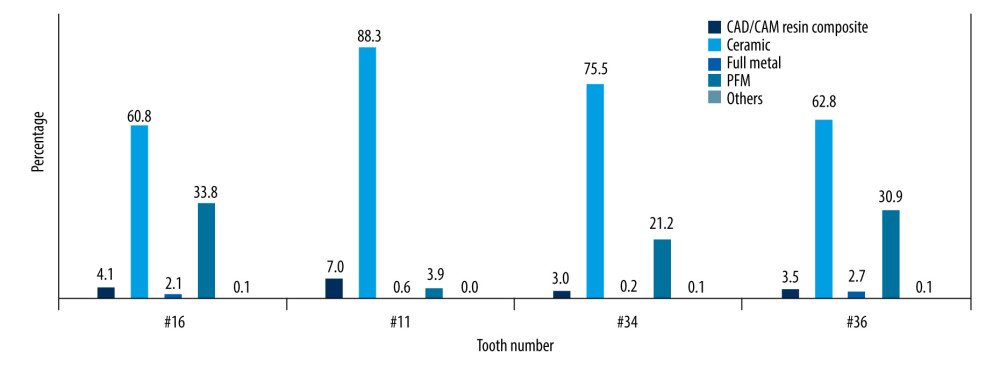

Dentists in general prefer dental ceramics followed by PFMs independent of the supra- and subgingival preparation margins in posterior teeth and ceramics, followed by CAD/CAM-based resin SC for anterior teeth (Figures 3, 4).

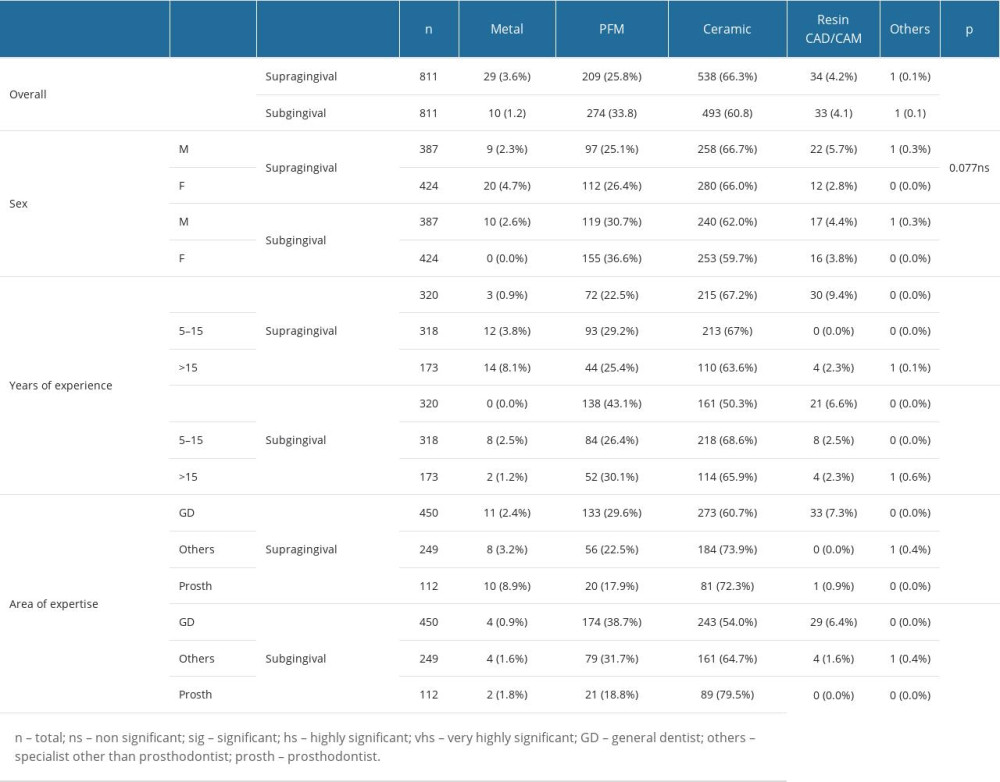

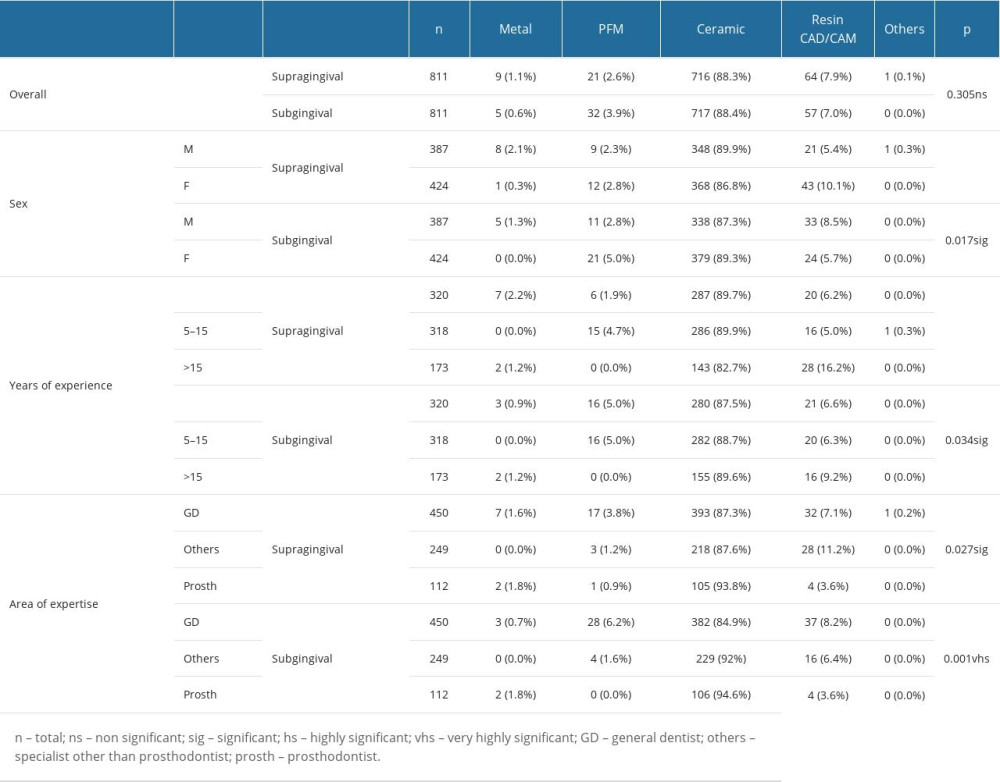

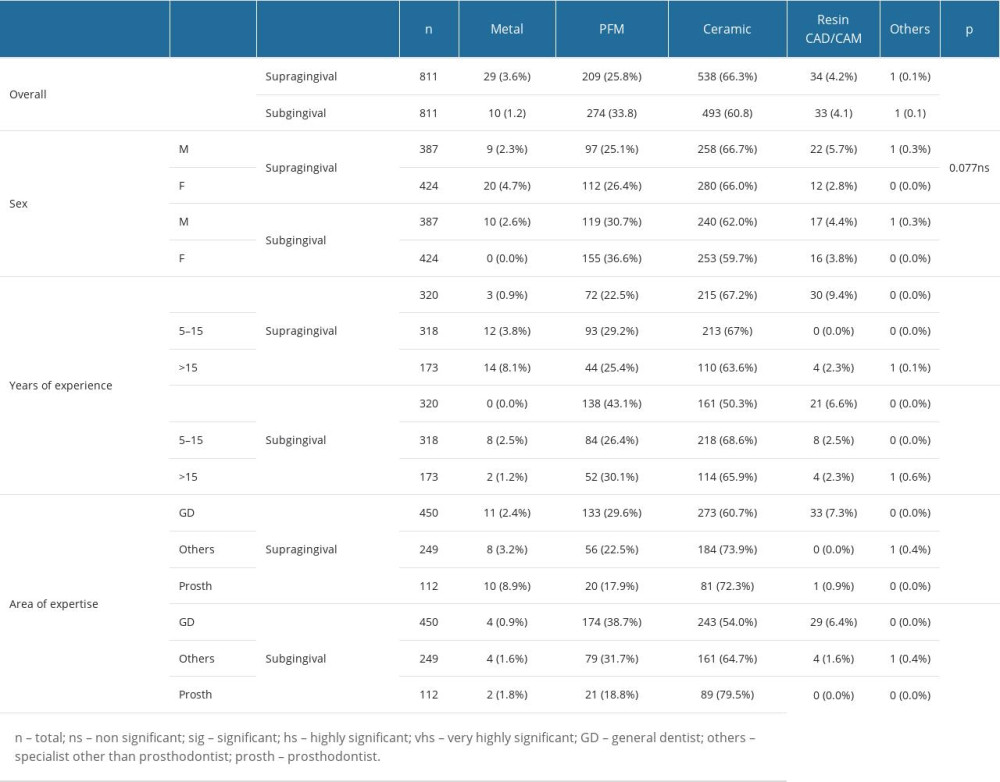

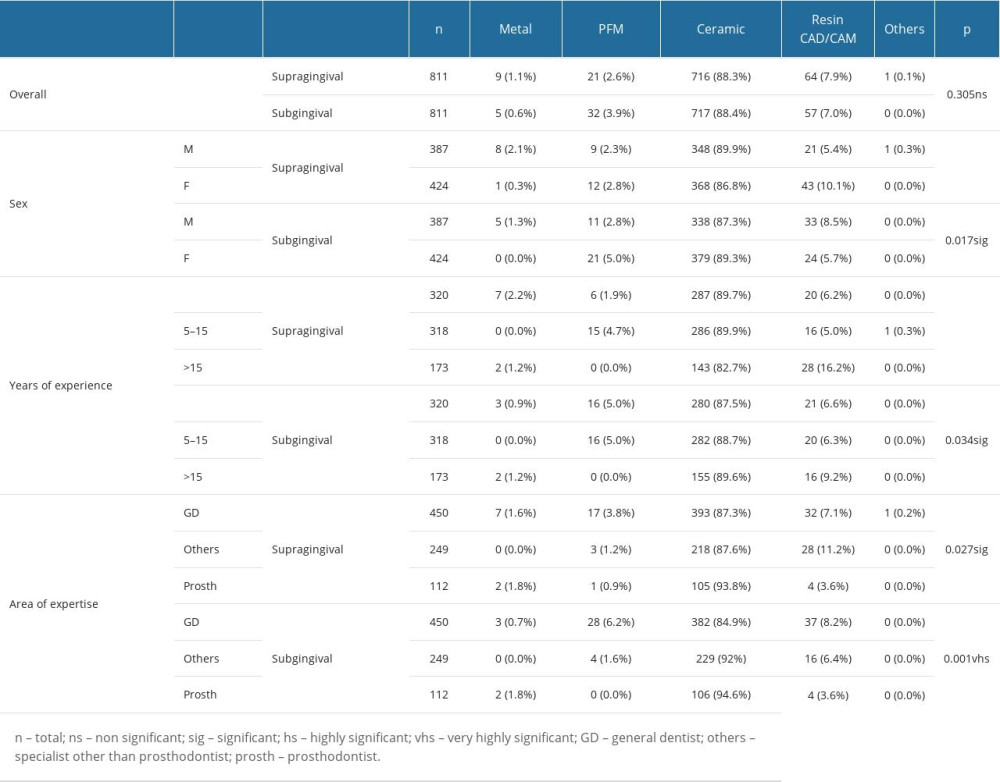

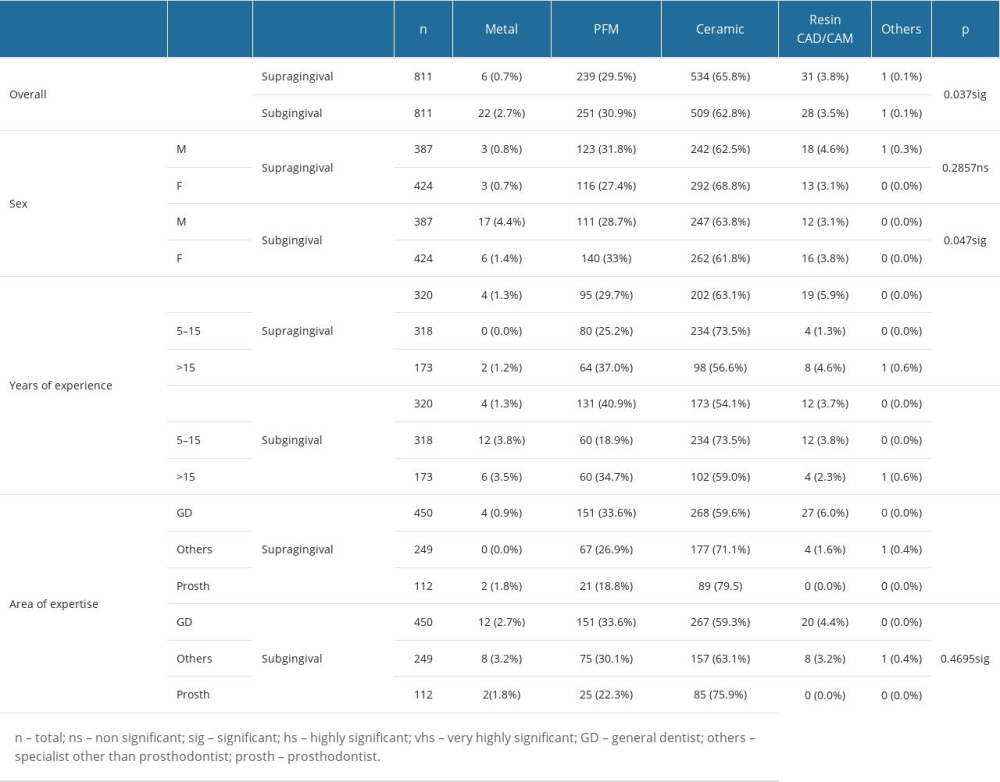

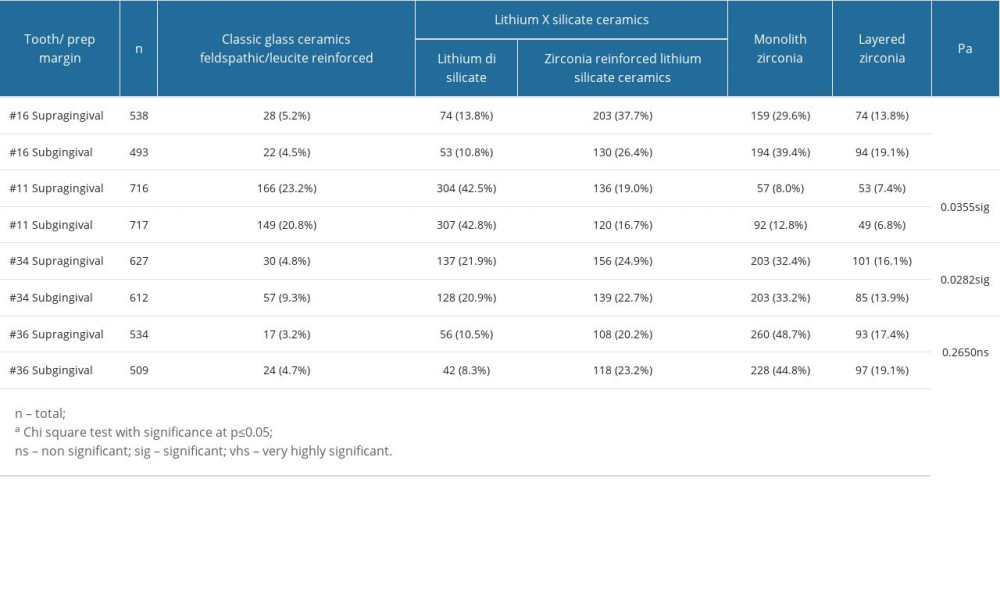

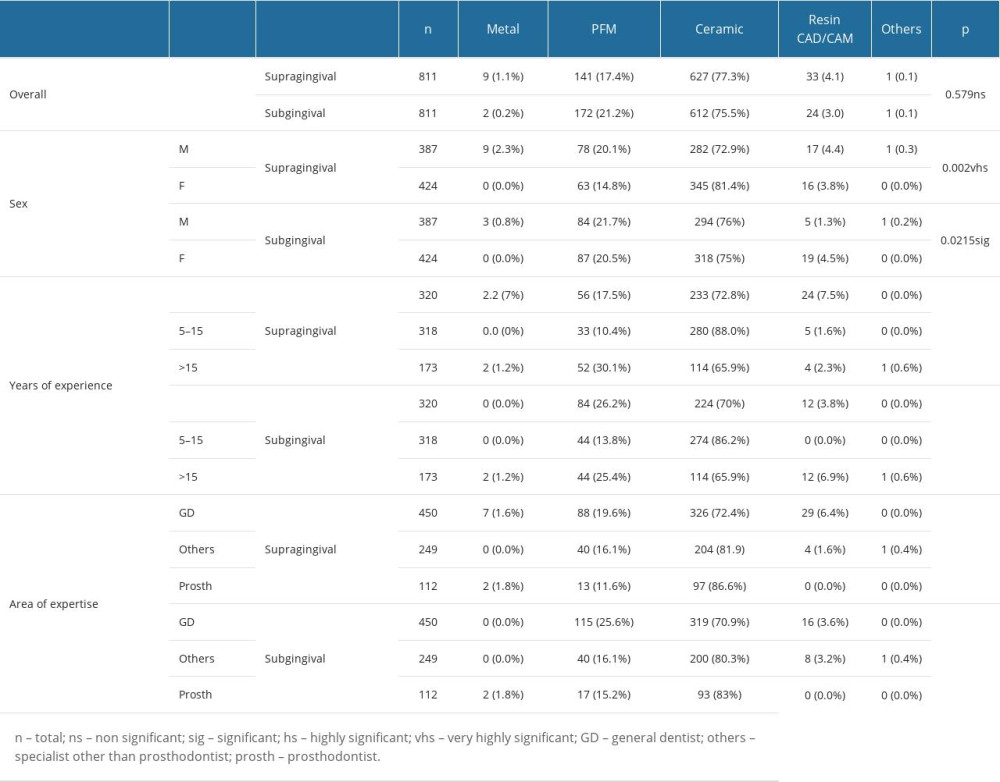

Significant differences were seen in responses of participating dentists based on gender in tooth number 16 with subgingival margins. With regards to experience and area of expertise, significant differences were noted in both supragingival and subgingival preparations. Interestingly, recent graduates with <5 years of experience and general dentists preferred the use of CAD/CAM-based resin SC more than their more experienced counterparts. General dentists preferred CAD/CAM-based resin crowns for tooth number 11 and preferred PFM crowns in teeth with subgingival margins (Tables 1, 2).

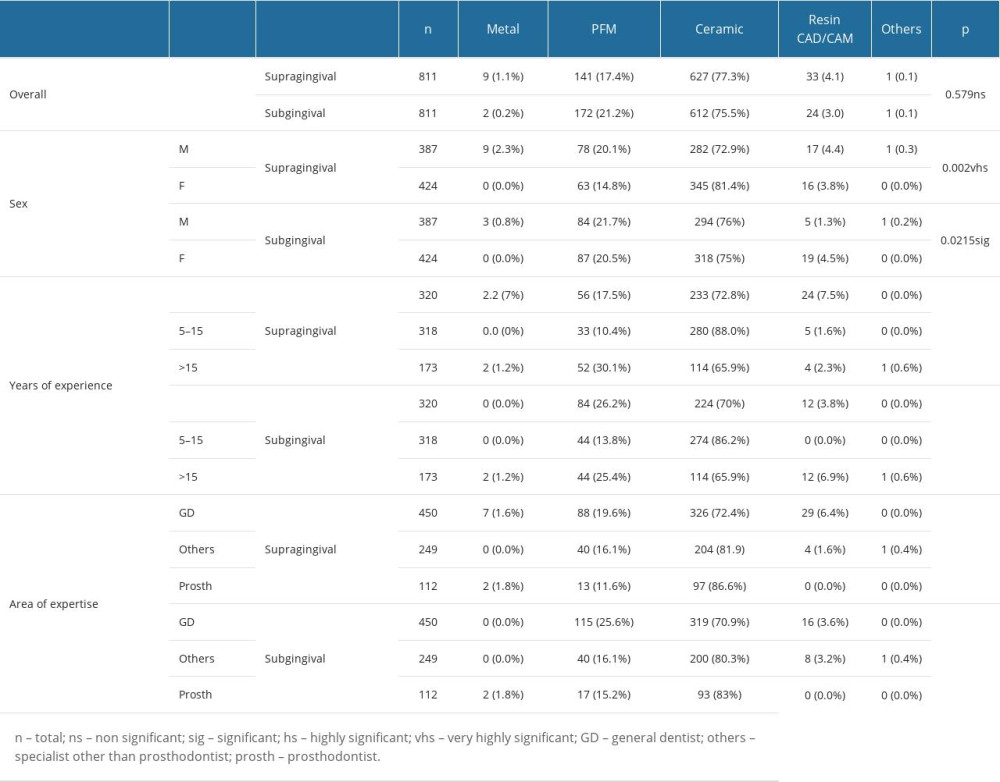

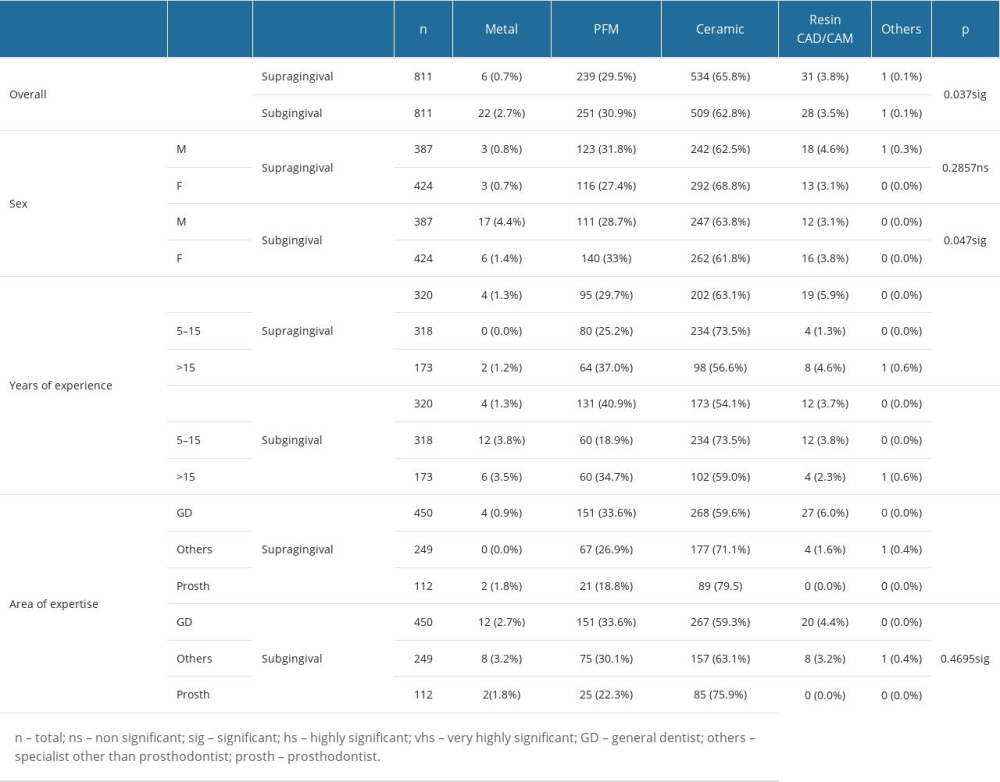

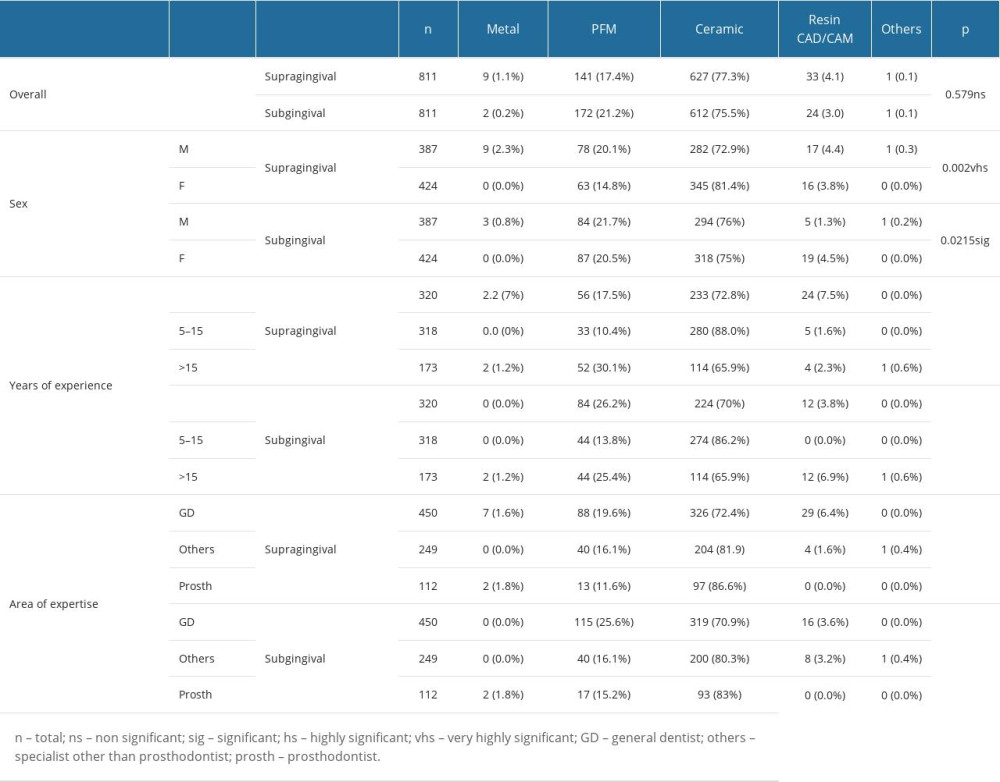

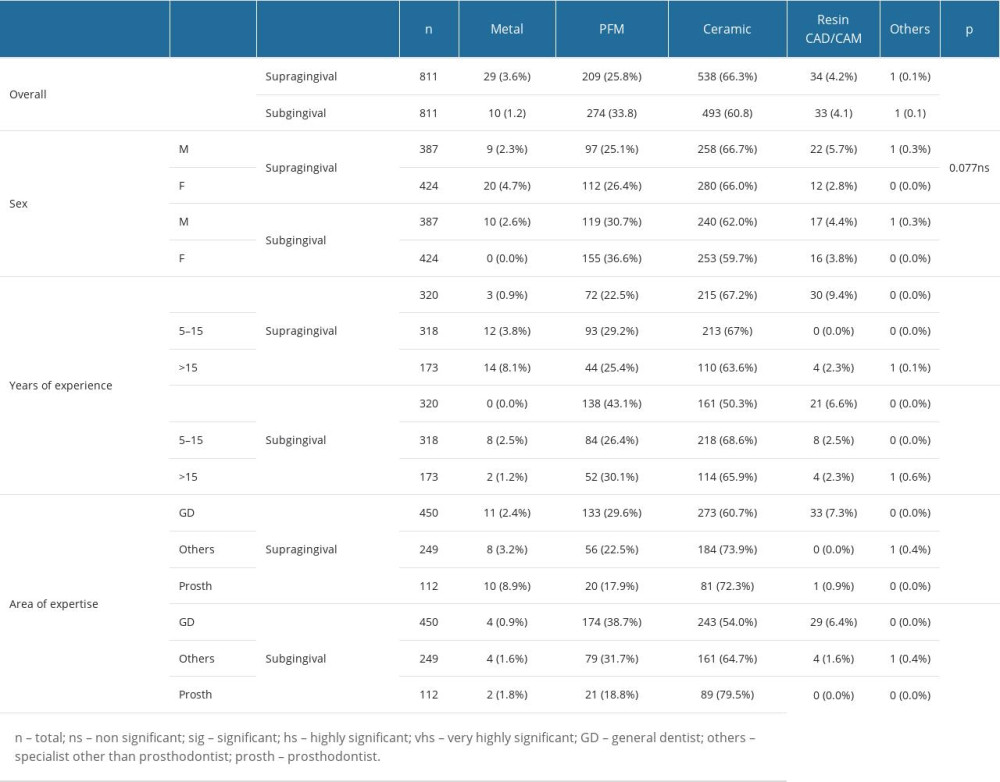

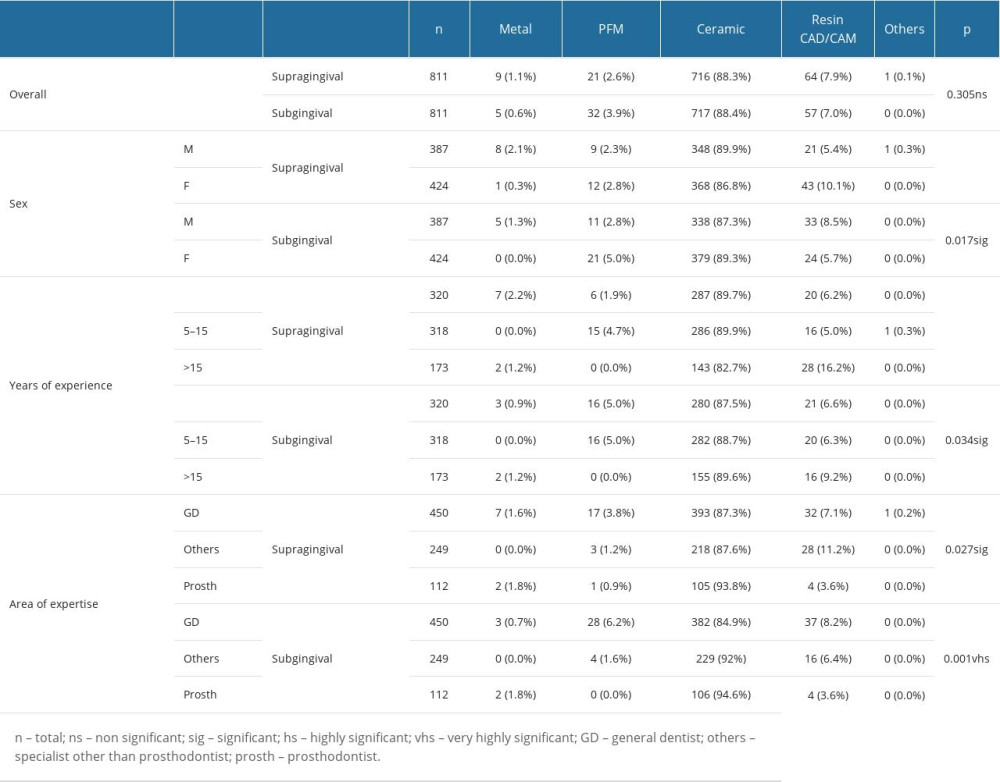

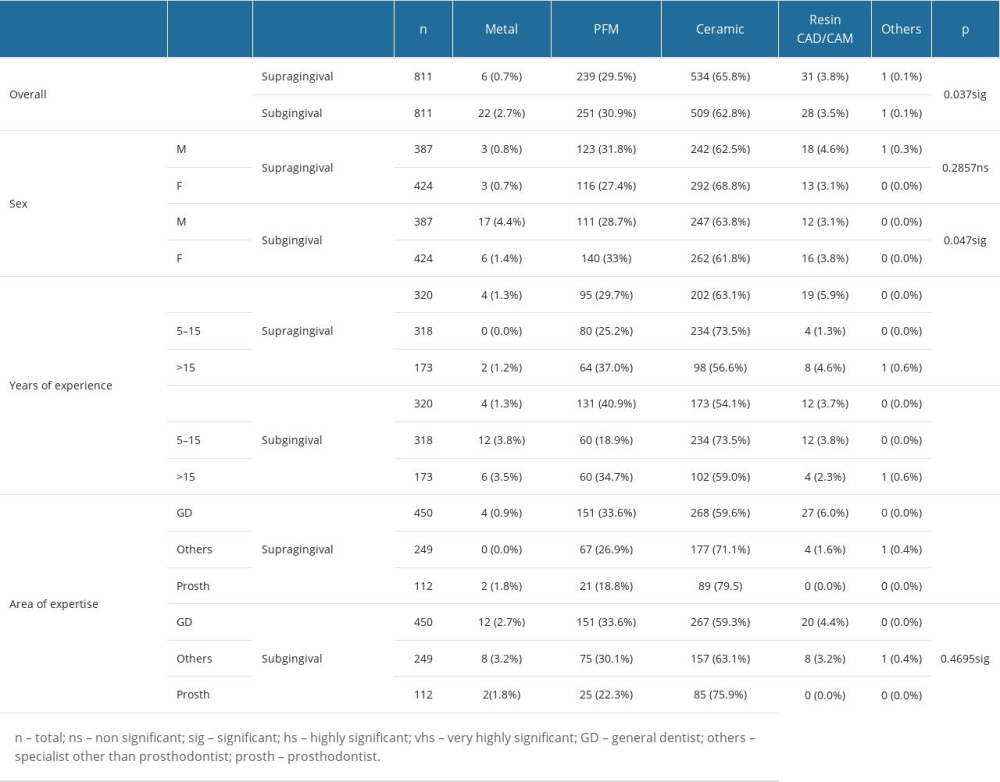

In the lower arch as well, the response was highly significant based on gender, area of expertise, and years of experience among both supragingival and subgingival margins. Other than ceramics, for tooth no. 34, male dentist chose PFM more often and female dentist preferred to use CAD/CAM-based resin crowns and vice versa for tooth number 36. Compared to female dentists, more male dentists preferred metal SC. Similar to the maxillary arch, general dentists and those with less than 5 years of experience tended to prefer CAD/CAM resin SC (Tables 3, 4).

DENTIST’S PREFERENCES REGARDING MATERIALS FOR SC WITH SUPRAGINGIVAL PREPARATION:

Ceramic was the most preferred material for SC regardless of the abutment tooth location, with a range of 66.3–88.3%. The preference for ceramic material among Saudi dentist gradually increased from posterior to anterior teeth assessed in this study, and PFM was the second-most preferred material, with a range of 2.6–29.5%. However, unlike the ceramic preference, the choice for PFM gradually decreased from posterior teeth to the teeth more anteriorly located, with the

Lowest preference being 2.6% for tooth number 11. CAD/CAM-based resin SC were preferred by 3.8–7.9% of the dentists, most often for the anterior tooth. Crowns made of metal were the least preferred (0.7–3.6%) among all the materials (Tables 1–4).

DENTISTS’ PREFERENCES REGARDING MATERIALS FOR SC WITH SUBGINGIVAL PREPARATION:

Similar to the preference in supragingival margins, ceramic was material favored by dentists for teeth with subgingival margins (60.8–88.4%), irrespective of the abutment tooth site, with preference being highest in anterior teeth. PFM crowns were preferred by 3.9–33.8% of dentists. The choice was influenced by the tooth location, and its preference increased in more posterior teeth. This was followed by the CAD/CAM-based resin SC, preferred by 3–7% of dentists. As in teeth with supragingival margins, resin crowns were a more common choice in anterior teeth compared to other sites. Metal crowns were least preferred, with the highest preference of 2.7% in tooth 36 (Tables 1–4).

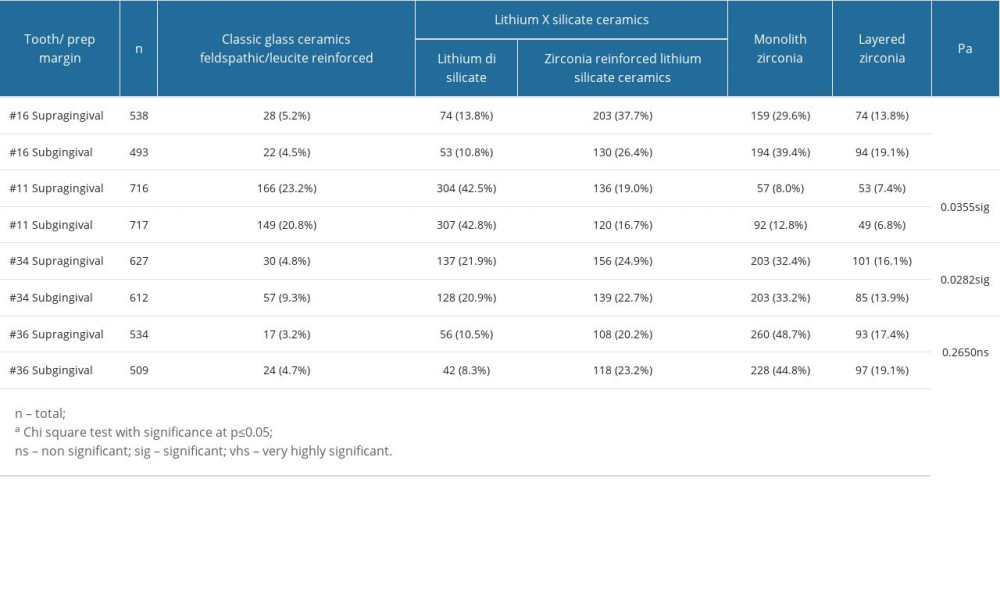

COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT CERAMIC MATERIALS BETWEEN SUPRAGINGIVAL AND SUBGINGIVAL PREPARATION MARGINS:

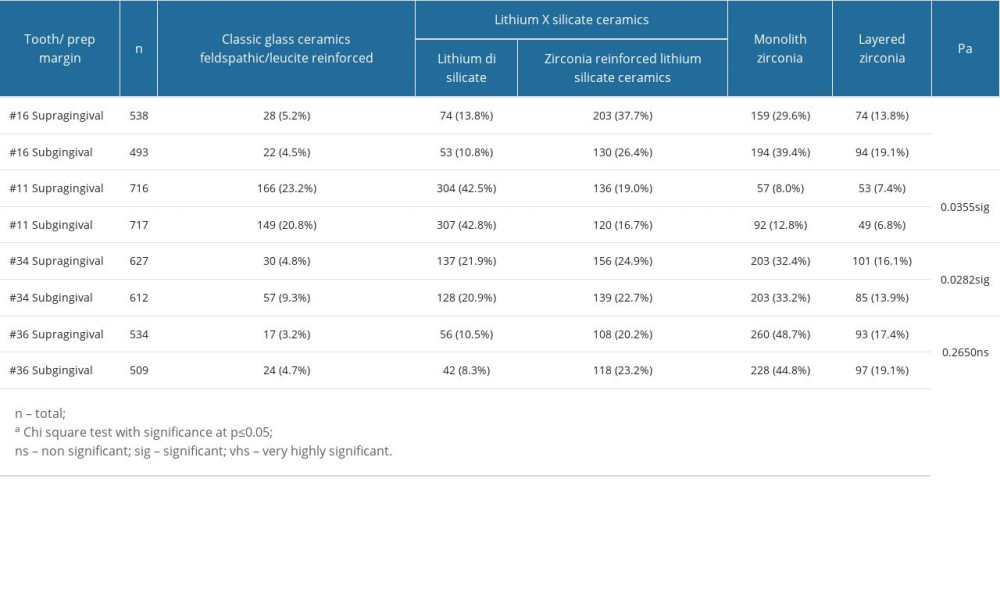

Among the choice of ceramic in teeth with supragingival margins, monolith zirconia was most preferred (32.4–48.7%) material for SC fabrication in posterior teeth, followed by zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramic (24.9–37.7%). Classical feldspathic/leucite-reinforced glass ceramics (3.2–5.2%) was the least preferred. For the anterior teeth, lithium disilicate ceramic was the material preferred by 42.5% of dentists, followed by glass ceramics, and layered zirconia was the least favored (7.4%).

Between the choice of ceramics for teeth with subgingival margins, monolith zirconia crowns were the most-selected option in posterior teeth (33.2–44.8%) among the respondents, with highest in the mandibular molar region. In the anterior region, layered zirconia was least preferred (6.8%) and lithium disilicate ceramics (42.8%) was the most-favored option. A statistically significant difference existed between supra- and subgingival preparation for teeth numbers 11, 16, and 34 (Table 5).

Discussion

We found that dentists tended to prefer ceramics for fabricating SC, irrespective of the location of the abutment tooth and preparation margin. PFM was the second-most preferred crown material, followed by resin-based CAD/CAM resin composites, and metal crown were favored by only a few dentists. The study’s results are in line with the findings of Makhija et al, who also reported a preference for ceramic over PFM or full-metal crowns [2]. This increase in preference and application of ceramics for SC also could be because they have outstanding optical properties, and are extremely biocompatible, with low degradation levels compared to metal alloys [19]. Nevertheless, PFM still is a popular choice among dentist in Saudi Arabia and other parts of the word, as it has a long successful history of excellent clinical reliability [17,20,21]. Furthermore, in this study, the preference for CAD/CAM material can be attributed to advancements in digital technologies, exposure in dental school, or learning through continuing dental education.

Saudi dentists unanimously favored monolith zirconia in posterior teeth and lithium disilicate for anterior teeth for both supra- and subgingival margins, contrasting with their German counterparts, who chose lithium disilicate ceramics (31.1%) for supragingival margins and monolithic zirconia (28.1%) for subgingival preparation [17]. Also, studies show that both lithium disilicate and zirconia were the most commonly used materials for construction of posterior CAD/CAM crowns with supragingival margins for endo-crowns [22,23]. Monolith zirconia’s choice for posterior teeth could be due to its high flexural strength and fracture resistance compared to the inherently brittle feldspathic porcelain, or concern of about wearing of opposing natural teeth by feldspathic porcelain [5,24]. A similar choice of zirconia for fabricating posterior crowns was also seen among 277 respondents in a study conducted by the ADA panel [25]. In fact, a study conducted in 2013, among dental schools in America suggested the shift of material preference from feldspathic porcelain to zirconia (80%) within a span of 10–15 years due to greater strength and clinical longevity similar to PFM [26,27].

Lithium disilicate and zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramics were most commonly preferred due to their high translucency and flexural strength, and when used in the anterior region, exhibited a survival rate of 96.6–97.4% [10]. The choice was partly in harmony with dentists in Germany, India, and the USA [2,17,28]. Although not as frequently as lithium disilicate materials, monolith zirconia was also chosen by Saudi dentists for fabrication SC in the anterior region to a higher extent than layered zirconia due to lowered alumina content improving its translucency [5]. In fact, in a 5-year fracture rate study conducted to compare monolith and layered zirconia in the anterior and posterior regions, an average fracture rate of 0.71% was seen in monolith zirconia, whereas layered zirconia had a fracture rate of 3.25% [29]. Other studies have also revealed feldspathic porcelain to have higher failure rates in anterior teeth [30].

This study illustrated that material preference for SC is related with years of experience, area of expertise, location of the abutment tooth, and type of preparation margins. In contrast, Burke et al found that such factors did not significantly influence the selection or survival of porcelain veneer restorations [31]. Preference for full-metal among dentists who graduated less than 5 years ago was very low, and those with more clinical experience preferred PFM crowns compared to other dentists. This may be due to an understanding of the dental materials from experience or little exposure to ceramics in dental school [32]. Notably, in a study of German dentists on the material selection of three-unit fixed partial dentures, the time since graduation was a significant factor associated with material choice preference [33].

Preferences associated with the properties of dental restorations differ between dental professionals across the globe. A recent Cochrane review group suggested that dentists base their decisions on clinical situations, patient needs, and past experience [34]. It is mainly determined by esthetic considerations and mechanical parameters such as the stability and span of the edentulous space and level of gingival margins in the aesthetic zone [35,36]. Fabrication time could also be a factor in considering CAD/CAM-based ceramic restorations because they can be performed quickly in a single chairside session with no extra lab work [37]. In this study, prosthodontists preferred dental ceramics, PFMs, and full-metal, similar to the study by Rahman et al [38]. In contrast, Danish and Norwegian dentists attach more importance to the longevity of restorations rather than esthetics, and favored metal-based restorations over ceramics [39]. However, a systematic review of SC revealed that PFM, lithium disilicate, leucite-reinforced, and zirconia restorations exhibited statistically similar 5-year survival rates [3]. The null hypothesis is accepted as the material choice remained constant irrespective of tooth location and margin position.

Limitations of the present study could be that most of the dentists are familiar with the commercial names of ceramics provided by manufacturers rather than the material categories as assessed in this study. This could have led to response bias and variations in the results. Furthermore, source of information about choosing the materials could have been evaluated. Moreover, material choice for SC prostheses also depends on the type of practice – private or public-funded – and whether the payment mechanism is direct or insurance-based. Since we did not include these independent variables in our work, their influence on the primary outcome could not be elucidated. Hence, prospective studies based on direct clinical observation would be more precise. The strength of our study lies in the sufficient sample size for internal validity.

Conclusions

The top 3 choices for anterior and posterior teeth were dental ceramics, PFMs, and resin-based CAD/CAM. Among ceramics, lithium disilicate was the most preferred material. Many dentists favored ceramics, especially for anterior crowns, reflecting the importance of esthetics in the anterior region. For posterior crowns, durability and strength were prioritized, with a preference for monolithic zirconia. PFM crowns were the next-preferred option, with a declining trend from posterior to anterior locations, while CAD/CAM-based resin crowns were more popular among younger and less-experienced dentists.

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 16 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch). Table 2. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 11 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch).

Table 2. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 11 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch). Table 3. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 34 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch).

Table 3. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 34 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch). Table 4. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 36 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch).

Table 4. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 36 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch). Table 5. Comparison of selection of dental crown materials between supra- and subgingival preparation margins of various abutment teeth.

Table 5. Comparison of selection of dental crown materials between supra- and subgingival preparation margins of various abutment teeth.

References

1. Shi HY, Pang R, Yang J, Overview of several typical ceramic materials for restorative dentistry: Biomed Res Int, 2022; 2022; 8451445

2. Makhija SK, Lawson NC, Gilbert GH, Dentist material selection for single-unit crowns: Findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network: J Dent, 2016; 55; 40-47

3. Sailer I, Makarov NA, Thoma DS, All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part I: Single crowns (SCs): Dent Mater, 2015; 31; 603-23

4. Kwon SJ, Lawson NC, McLaren EE, Comparison of the mechanical properties of translucent zirconia and lithium disilicate: J Prosthet Dent, 2018; 120; 132-37

5. Li RW, Chow TW, Matinlinna JP, Ceramic dental biomaterials and CAD/CAM technology: State of the art: J Prosthodont Res, 2014; 58; 208-16

6. Warreth A, Elkareimi Y, All-ceramic restorations: A review of the literature: Saudi Dent J, 2020; 32; 365-72

7. Al Moaleem MM, Al Ahmari NM, Alqahtani SM, Unlocking endocrown restoration expertise among dentists: Insights from a multi-center cross-sectional study: Med Sci Monit, 2023; 29; e940573

8. Homaei E, Farhangdoost K, Tsoi JKH, Static and fatigue mechanical behavior of three dental CAD/CAM ceramics: J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, 2016; 59; 304-13

9. Hwang MH, Kim HR, Kwon TY, Repairing fractured ceramic veneer with CAD/CAM ceramic blocks: A preliminary tensile bond strength study: Materials Tech, 2019; 34; 43-50

10. Elsaka SE, Elnaghy AM, Mechanical properties of zirconia reinforced lithium silicate glass-ceramic: Dent Mater, 2016; 32; 908-14

11. Sen N, Us YO, Mechanical and optical properties of monolithic CAD-CAM restorative materials: J Prosthet Dent, 2018; 119; 593-99

12. Fouda AM, Atta O, Özcan M, An investigation on fatigue, fracture resistance, and color properties of aesthetic CAD/CAM monolithic ceramics: Clin Oral Investig, 2023; 27; 2653-65

13. Villa HL, Brindis M, Lawson NC, Material selection for single-unit crown anterior restorations: Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2020; 41; 477-82

14. El Makawi Y, Khattab N, In vitro comparative analysis of fracture resistance of lithium disilicate endocrown and prefabricated zirconium crown in pulpotomized primary molars: Open Access Maced J Med Sci, 2019; 7; 4094-100

15. Zürcher AN, Hjerppe J, Studer S, Clinical outcomes of tooth-supported leucite-reinforced glass-ceramic crowns after a follow-up time of 13–15 years: J Dent, 2021; 111; 103721

16. de Kuijper M, Gresnigt MMM, Kerdijk W, Cune MS, Shear bond strength of two composite resin cements to multiphase composite resin after different surface treatments and two glass-ceramics: Int J Esthet Dent, 2019; 14; 40-50

17. Rauch A, Schrock A, Schierz O, Hahnel S, Material selection for tooth-supported single crowns – a survey among dentists in Germany: Clin Oral Investig, 2021; 25; 283-93

18. Haider Y, Dimashkieh M, Rayyan M, Survey of dental materials used by dentists for indirect restorations in Saudi Arabia: Int J Prosthodont, 2017; 30; 83-85

19. Vianna ALSV, Prado CJD, Bicalho AA, Effect of cavity preparation design and ceramic type on the stress distribution, strain and fracture resistance of CAD/CAM onlays in molars: J Appl Oral Sci, 2018; 26; e20180004

20. Schwass DR, Lyons KM, Purton DG, How long will it last? The expected longevity of prosthodontic and restorative treatment: N Z Dent J, 2013; 109; 98-105

21. Lekesiz H, Reliability estimation for single-unit ceramic crown restorations: J Dent Res, 2014; 93; 923-28

22. Alwadai GS, Al Moaleem MM, Daghrery RA, A comparative analysis of marginal adaptation values between lithium disilicate glass ceramics and zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate endocrowns: A systematic review of in vitro studies: Med Sci Monit, 2023; 29; e942649

23. Al Ahmari NM, Gadah TS, Wafi SA, Relationship between tooth type and material used in the construction of endocrowns and fracture force values: A systematic review: Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2023; 27; 7665-79

24. Liao Y, Gruber M, Lukic H, Fracture toughness of zirconia with a nanometer size notch fabricated using focused ion beam milling: J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, 2020; 108; 3323-30

25. Lawson NC, Frazier K, Bedran-Russo , Zirconia restorations: An American Dental Association clinical evaluators panel survey: J Am Dent Assoc, 2021; 152; 80-81

26. Christensen GJ, Is the rush to all-ceramic crowns justified?: J Am Dent Assoc, 2014; 145; 192-94

27. Carrabba M, Keeling AJ, Aziz A, Translucent zirconia in the ceramic scenario for monolithic restorations: A flexural strength and translucency comparison test: J Dent, 2017; 60; 70-76

28. Talkal AK, Vijaykumar N, Swamy MC, A survey among dentists in India to identify their favored materials for the fabrication of tooth-supported single crowns depending on the location of the abutment teeth and the preparation margin: Int J Oral Care Res, 2022; 10; 81-84

29. Abdulmajeed AA, Donovan TE, Cooper LF, Fracture of layered zirconia restorations at 5 years: A dental laboratory survey: J Prosthet Dent, 2017; 118; 353-56

30. Olley RC, Andiappan M, Frost P, An up to 50-year follow-up of crown and veneer survival in a dental practice: J Prosthet Dent, 2017; 19; 935-41

31. Burke FJ, Lucarotti PS, Ten-year outcome of porcelain laminate veneers placed within the general dental services in England and Wales: J Dent, 2009; 37; 31-38

32. Rekow ED, Bayne SC, Carvalho RM, Steele JG, What constitutes an ideal dental restorative material?: Adv Dent Res, 2013; 25; 18-23

33. Rauch A, Material preferences for tooth-supported 3-Unit Fixed Dental Prostheses: A survey of German dentists: J Prosthet Dent, 2021; 126; 91e1-e6

34. Poggio CE, Ercoli C, Rispoli L, Metal-free materials for fixed prosthodontic restorations: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017; 12; CD009606

35. Singh BP, Kamleshwar S, Nishi S, Kumari R, Current trends and practices followed by dental technicians and dentists in fixed crown and bridges in India: A cross-sectional survey: Int J Prosth Resto Dent, 2013; 3; 43-49

36. Kamli EA, Zailai AM, Sabyei MY, Combined effect of mineral trioxide aggregate and customized glass fiber post in nonsurgical endodontic retreatment teeth at esthetic zone: A case report: World J Dent, 2023; 14(3); 273-80

37. Espelid I, Cairns J, Askildsen JE, Preferences over dental restorative materials among young patients and dental professionals: Eur J Oral Sci, 2006; 114; 15-21

38. Rahman MSU, Dubbaka P, Sahani S, Prosthodontists choice on selection of anterior and posterior crowns for prosthetic rehabilitation: A Cross Sectional Study: J Adv Med Dent Sci Res, 2020; 8; 50-52

39. Ziyad TA, Abu-Naba’a LA, Almohammed SN, Optical properties of CAD-CAM monolithic systems compared: Three multi-layered zirconia and one lithium disilicate system: Heliyon, 2021; 7; e08151

Figures

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 16 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch).

Table 1. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 16 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch). Table 2. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 11 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch).

Table 2. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 11 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch). Table 3. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 34 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch).

Table 3. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 34 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch). Table 4. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 36 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch).

Table 4. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 36 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch). Table 5. Comparison of selection of dental crown materials between supra- and subgingival preparation margins of various abutment teeth.

Table 5. Comparison of selection of dental crown materials between supra- and subgingival preparation margins of various abutment teeth. Table 1. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 16 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch).

Table 1. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 16 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch). Table 2. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 11 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch).

Table 2. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 11 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (upper arch). Table 3. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 34 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch).

Table 3. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 34 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch). Table 4. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 36 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch).

Table 4. Comparison of preferred crown materials for tooth number 36 (supra- and subgingival) with dentists’ characteristics (lower arch). Table 5. Comparison of selection of dental crown materials between supra- and subgingival preparation margins of various abutment teeth.

Table 5. Comparison of selection of dental crown materials between supra- and subgingival preparation margins of various abutment teeth. In Press

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952