08 February 2024: Database Analysis

High Prevalence of Antibodies in Jaworzno, Poland: A Retrospective Study Revealing Endemic Lyme Borreliosis

Barbara Koleżyńska12ABCDEF*, Krzysztof Solarz3DE, Weronika Wieczorek4E, Dorota Sagan5F, Dariusz Boroń67E, Rafał Staszkiewicz89E, Dawid Sobański10E, Tomasz Sirek11F, Anna Janik6F, Piotr ŁojkoDOI: 10.12659/MSM.943203

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e943203

Abstract

BACKGROUND: This retrospective study of 704 adult residents of Jaworzno, Poland, aimed to evaluate medical personnel awareness of episodes of Lyme borreliosis and serum antibody levels for Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: This study included 704 residents of Jaworzno, Poland, who had no more than 12 months between tick bite and screening. The study consisted of a self-designed questionnaire survey and an analysis of IgG and IgM antibodies against B. burgdorferi sensu lato using an enzyme-linked assay (ELISA) and Western blot analysis, when necessary, to confirm the results.

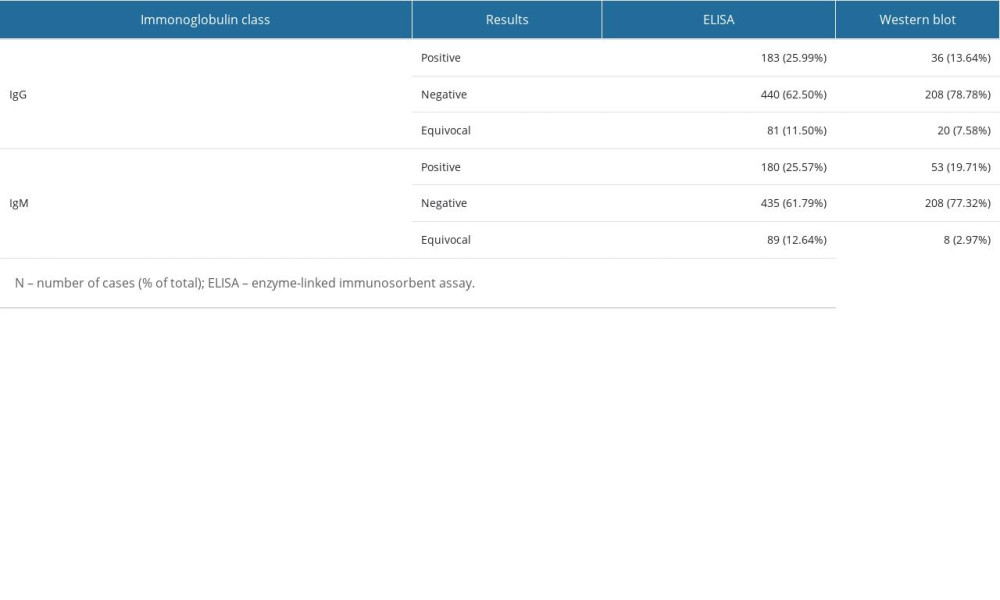

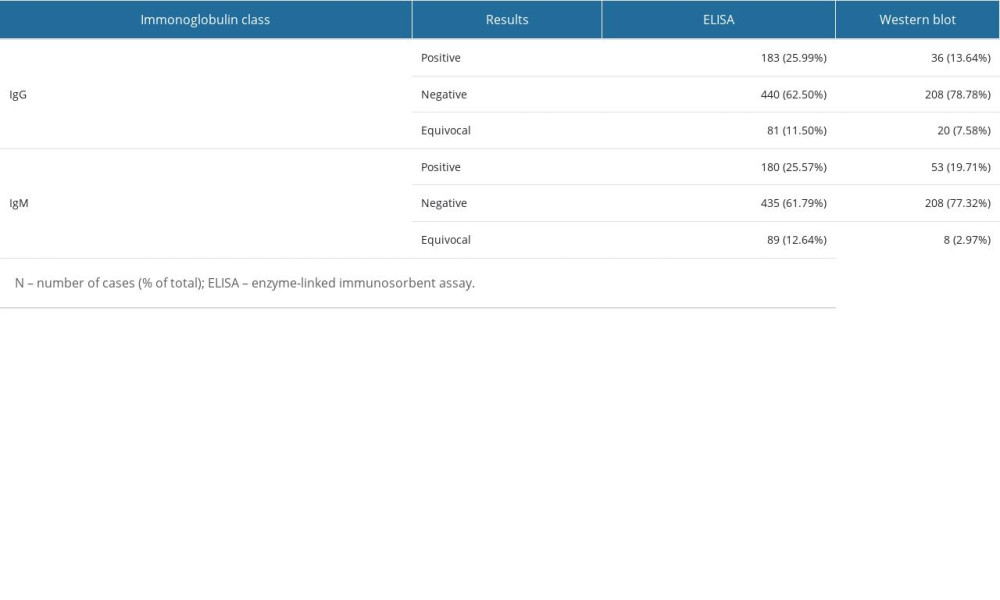

RESULTS: A total of 558 residents (79.3%) confirmed having contact with a tick, 84 (11.9%) responded that they did not remember having contact with a tick, and 62 (8.8%) denied having contact with a tick. Regarding IgG, the ELISA showed 183 (25.99%) positive, 440 (62.5%) negative, and 81 (11.5%) equivocal results. Regarding IgM, the ELISA showed 180 (25.57%) positive, 435 (61.79%) negative, and 89 (12.64%) equivocal results. Positive and equivocal results for the IgG and IgM classes using the ELISA test were confirmed in 36 cases (13.64%) for IgG and in 53 cases (19.70%) for IgM using Western blot analysis.

CONCLUSIONS: The ELISA method obtained similar values for positive, negative, and equivocal results in the serological test. This was reflected in the survey conducted on residents who reported a tick bite and later received a positive result in the ELISA test as well as an approximate time between the bite and removal of the tick.

Keywords: Antibodies, Anti-Idiotypic, Blotting, Western, Borrelia burgdorferi Group, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay, Epidemiology

Backgrond

Lyme borreliosis, also known as Lyme disease, is the most common tick-borne disease in Europe; it has been estimated that more than 200 000 people receive a diagnosis and treatment for this disease annually [1–3]. Its high occurrence rate results from human or animal contact with a tick infected with

The main vector of

To diagnose Lyme borreliosis, it is necessary to determine the specific IgM in the serum using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and to confirm this result using Western blot analysis [4]. However, the positive results of these tests do not always indicate an active disease [4]. The specific IgM class antibody is present in the blood of the infected individual from 3 weeks to 6 months after a tick bite, while the IgG class antibody appears after 6 weeks and can appear in the blood of the infected individual after recovery [4]. In a retrospective analysis that included 74 cases of patients with Lyme borreliosis and 122 controls, Hoeve-Bakker et al showed that there was little diagnostic value of IgM class antibody determination in screening for Lyme disease [12]. Therefore, positive IgM results for the diagnosis of Lyme disease should be approached with caution [12]. The multiplicity of

Therefore, this retrospective study of 704 adult residents of Jaworzno, Poland, aimed to evaluate medical personnel awareness of episodes of Lyme borreliosis and the serum antibody levels for

Material and Methods

ETHICS STATEMENT:

This study was approved by Resolution 03/KEBN/2023 of the Academy of Silesia, Katowice, Poland, regarding opinions on the medical experiment project. This study also obtained approval from the hospital director in Jaworzno, Poland, regarding the use of the research results for scientific purposes. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before they participated in this study, and consent was obtained for data publication after prior anonymization by the corresponding author. The hospital agreed to share anonymized patient data with the corresponding author. Data confidentiality and patient anonymity were maintained at all times. Patient-identifying information was deleted before the database was analyzed. It is impossible to identify patients individually from this article or the database. In addition, following ethical rules, the corresponding author observed professional secrecy.

SAMPLE SIZE CALCULATION:

According to data published by the Central Statistical Office (GSO), the number of residents in Jaworzno was 89 827 [14]. The number of necessary participants in the study was determined using the statistical tool available at https://www.naukowiec.org/dobor.html (accessed on 14 July 2022) [15]. For a population of 89827 residents, the maximum error value was estimated at 4%. Therefore, assuming that P<0.05, the required number of participants was 594 (P<0.05), and our study included 704 participants.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS:

A total of 704 patients were included in the study. Inclusion criteria were (1) patients provided their consent, (2) patients were registered as residents of Jaworzno, (3) patients had exposure to a tick bite, and (4) the period between the tick bite and the screening test was no longer than 12 months. The positive and equivocal results of the ELISA test were then confirmed using the Western blot test. This study covered residents of Jaworzno using the Lyme borreliosis screening campaign, financed by the Jaworzno City Council, as part of a prevention and health promotion campaign. The research was conducted at the Independent Public Healthcare Institution (SP ZOZ) of the Multispecialty Hospital in Jaworzno. The study group consisted of 704 patients, including men, women, and children, living in Jaworzno. Before the study, each patient completed a questionnaire regarding the time, location, and time of exposure to a tick bite, the duration the tick remained on the skin, and the disease symptoms associated with a tick bite that occurred immediately after the bite or in a time interval afterward. Information on possible treatments, especially antibiotic therapy after infestation, was also collected.

Only those patients who confirmed registration in the city of Jaworzno and gave informed, voluntary consent to participate in the study were included. Each of the 704 patients reported to the Independent Public Healthcare Institution of the Multispecialty Hospital in Jaworzno, Poland, to participate in the screening test and presented a document confirming their place of residence as Jaworzno, Poland.

SELF-DESIGNED QUESTIONNAIRE:

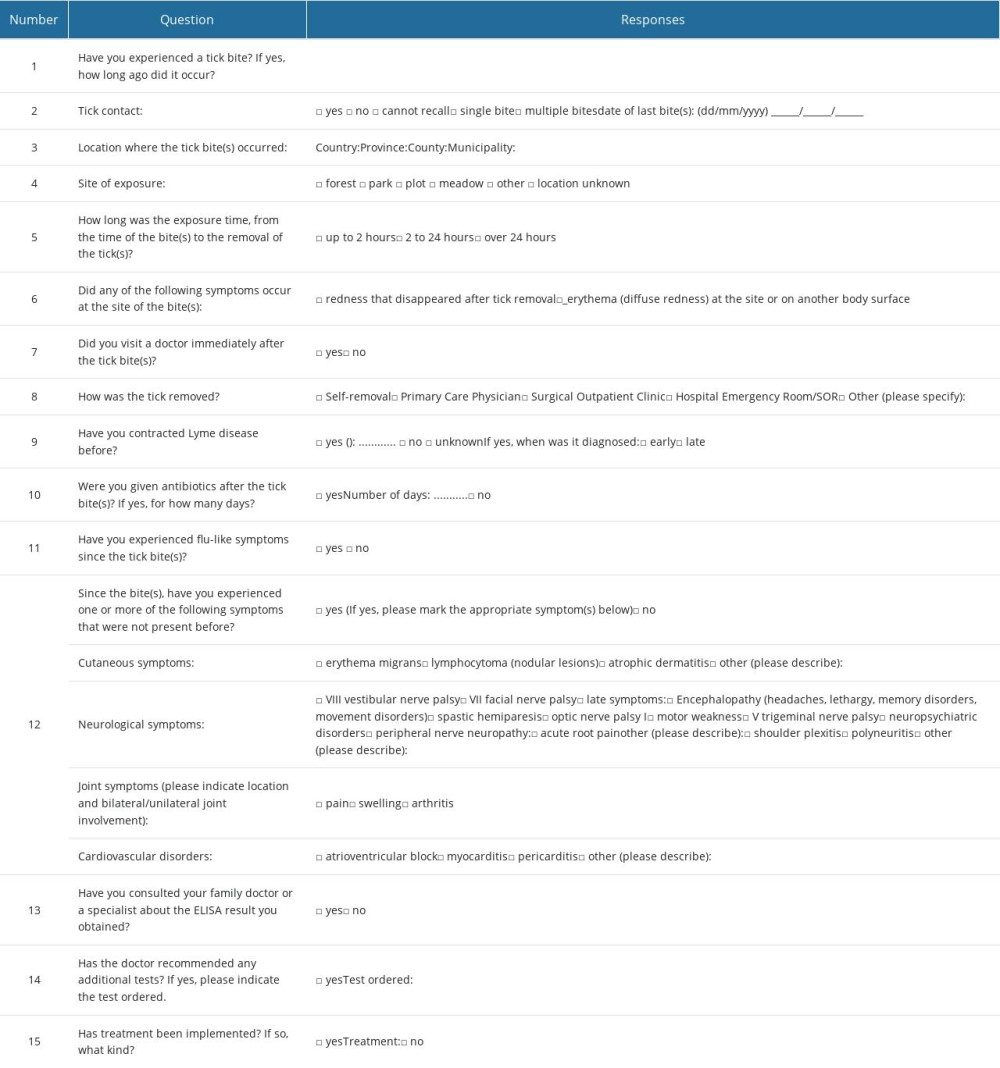

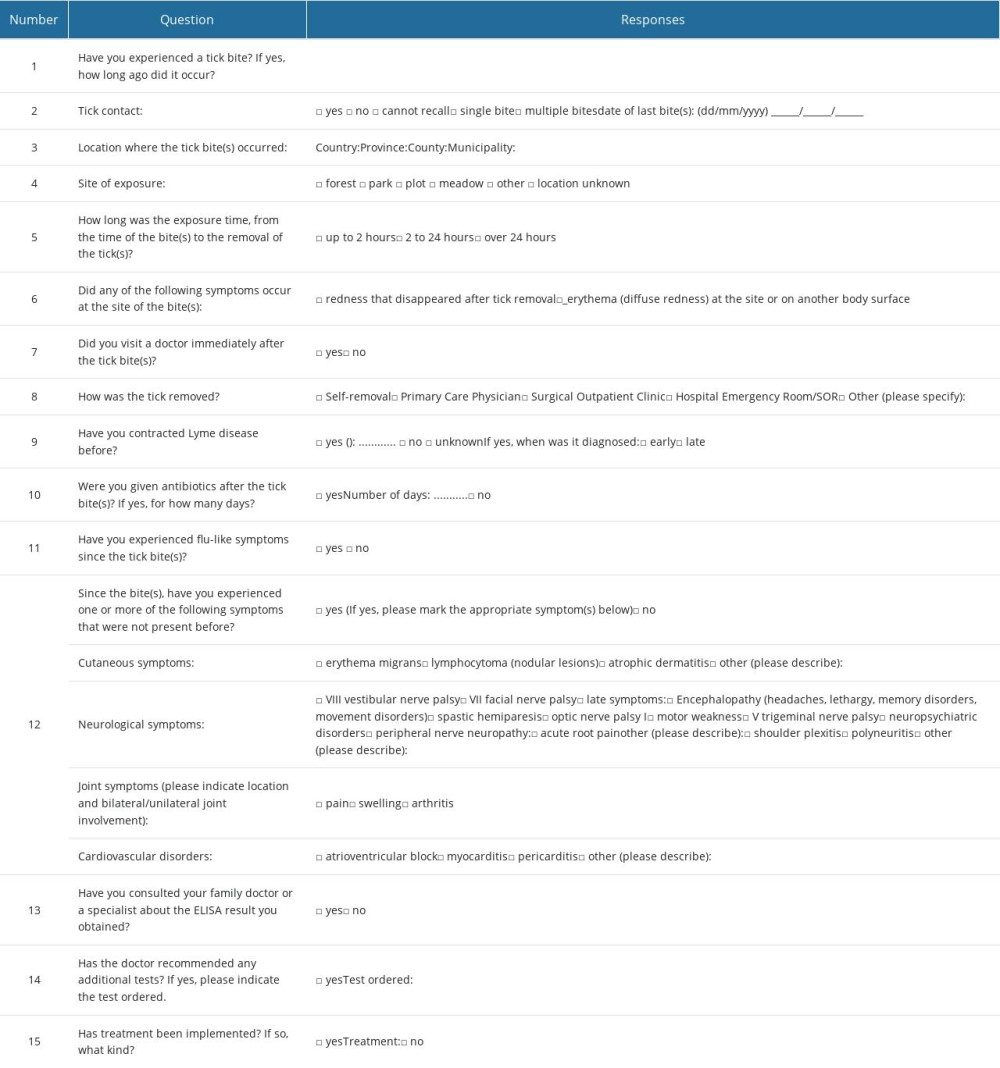

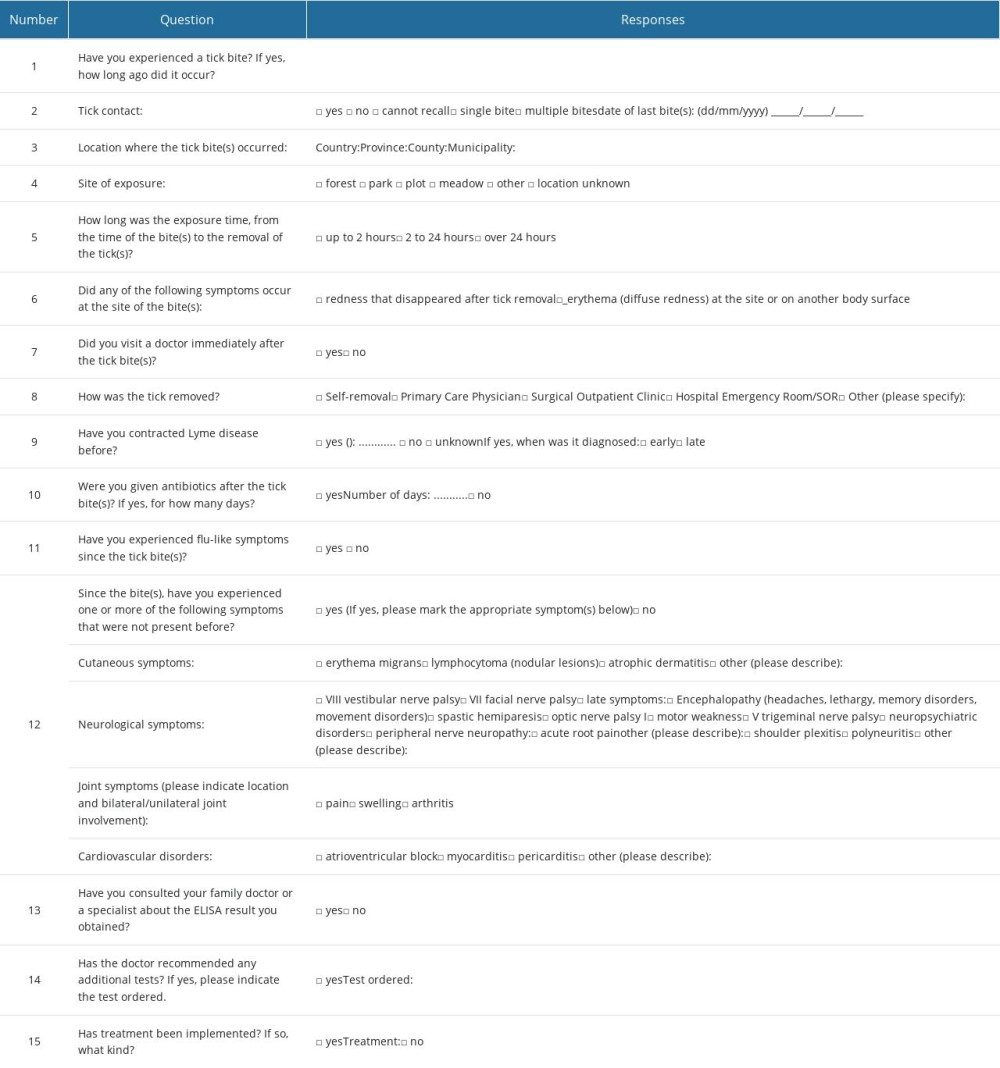

One of the conditions for participation in the study was to complete a questionnaire on exposure to tick bites, possible symptoms after the bite, performed treatment, and possible treatment. The absence of a tick bite was not included as an exclusion criterion for participation in the study, because of concerns that the patients would provide an inaccurate response. A questionnaire survey on tick bite exposure was conducted among people who indicated a desire to participate in the screening test. This questionnaire consisted of 3 parts: (1) personal details (sex, age, profession); (2) an epidemiological interview on exposure to ticks; and (3) a declaration of symptoms, symptom location, and symptom severity. The patients began participating in the study after receiving complete information about the purpose and methodology of the study. The questions, along with the suggested response options, are included in Table 1. Volunteers completing the survey were required to disclose personal information, such as sex, age, place of residence, occupation, and place of work.

On behalf of the hospital, the corresponding author prepared and led the campaign and developed the survey, which was positively accepted by the staff of the Health Department of the Jaworzno Municipal Office and the Ethics Committee of the Academy of Silesia, Katowice, Poland.

SECURING CLINICAL MATERIAL AND PRELIMINARY STEPS:

From a vein in the forearm, a blood sample of 5 mL was drawn into a “clot” tube. Each tube and laboratory test blank were labeled with a barcode containing encoded information about the patient (name, surname, PESEL number). Each blood sample collected for clotting was centrifuged to obtain serum, in which p/Borrelia antibodies in the IgM and IgG groups were determined using ELISA.

ANTIBODIES:

To evaluate antibodies in the IgG class, an ELISA test (Aeskulisa Borrelia-G, Aeksku.Group, Wendelsheim, Germany) was used as an enzymatic immunoassay based on a solid phase for the quantitative and qualitative detection of IgG antibodies against

To evaluate antibodies in the IgM class, we used an Aesculis Borrelia-M ELISA test (Aeksku.Group), a solid-phase enzyme immunoassay, for the quantitative and qualitative detection of IgM antibodies against

To interpret the results of IgG and IgM, the corresponding antibody concentration, in U/mL, was read from the optical density of each sample (normal concentration range, <12 U/mL; equivocal range, 12–18 U/mL; and positive result, >18 U/mL).

PROCEDURE:

The titer of antibodies against

First, the serum samples were diluted 1: 101 and incubated on microplates coated with specific antigens. Antibodies in the patient’s serum bound to the antigen on the plate. The fraction of unbound antibodies was washed in the next step of the test. A conjugate (anti-human immunoglobulin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase) was then applied to the plate. During incubation, the microplate reacted with the sample’s antigen/antibody complex. The excess conjugate was then washed. The addition of substrate (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) specific to the enzyme produced a color change using an enzymatic colorimetric reaction, which was stopped using dilute acid after a certain time (the color changed from blue to yellow). The magnitude of the 2 stains from the chromogen is a function of the amount of conjugate bound to the antigen-antibody complex and is proportional to the initial concentration of the specific antibodies in the patient’s sample.

PRELIMINARY STEP:

Half of the material obtained was frozen at −40°C until the ELISA results were obtained. If the ELISA results were positive or equivocal, they were validated using the Western blot test. Because the frozen blood sample constituted the test material, we did not need to invite the study participants in order to collect the material again.

ANTIBODIES:

The immunoblotting method was used to confirm the specificity of the antibodies detected using the ELISA test. Aeskublot Borrelia-G (Aeksku.Group) and Aeskublot Borrelia-M (Aeksku.Group) tests were used.

PROCEDURE:

Antigens were placed in precise positions on the nitrocellulose membrane, forming parallel rows. The following antigens were used: p100 (membrane vesicle protein); VlsE (

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF CONFIRMED DIAGNOSES OF B. BURGDORFERI SENSU LATO IN SILESIAN PROVINCE AND JAWORZNO BETWEEN 2016 AND 2022:

In the next stage, using the database of the Provincial Epidemiological Station in Katowice, Poland, the number of confirmed cases of

where k is the number of morbidities in the study population, and p is the number of people in the studied population.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The data were statistically analyzed after anonymization by the corresponding author. Statistical analysis was performed using STATISTICA 13 software (Statsoft, Krakow, Poland), with the statistical significance set at

Results

RESULTS OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE:

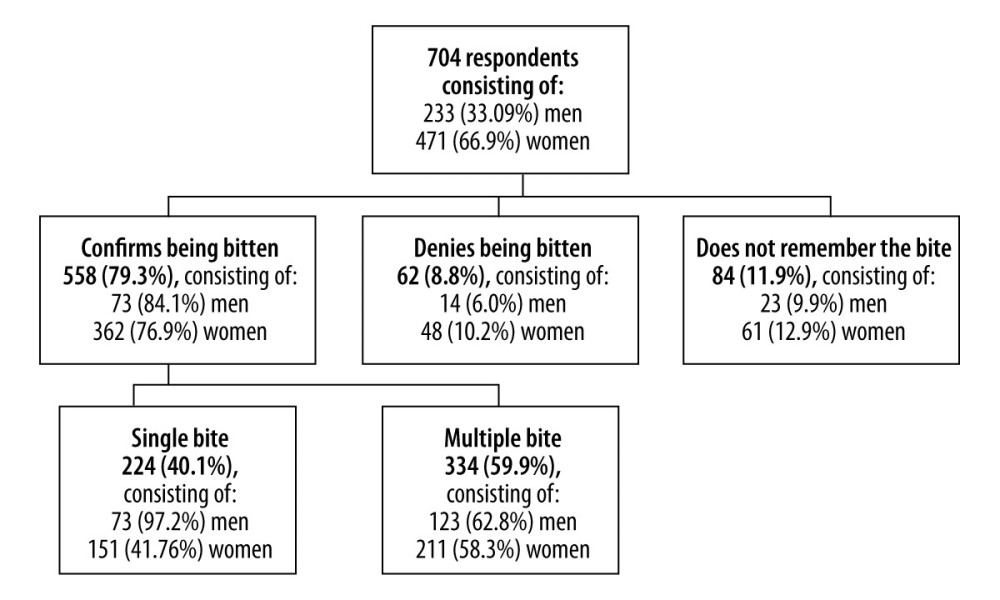

Among the residents of Jaworzno who qualified for the study, 558 (79.3%) confirmed having contact with a tick, of which 334 (59.9%) had multiple bites, and 224 (40.1%) had a single bite. Of the patients included in the study, 84 (11.9%) did not remember having contact with a tick, and 62 (8.8%) denied having contact with a tick. The frequency of occurrence of tick bites in the study group of patients is presented in Figure 1.

The common contact locations with the tick were reported as the forest (314, 44.6%), garden (188, 26.7%), meadow (55, 7.8%), park (40, 5.7%), and other (20, 2.8%), while 87 (12.3%) patients did not respond to the question. From the perspective of further therapeutic and diagnostic actions, the period from tick infestation to removal is essential. A total of 119 (16.95%) patients indicated that this period was <2 h, 317 (61.9%) indicated this time as 2 to 24 h, and 62 (8.8%) indicated that this time was >24 h. Of the patients, 100 (14.2%) were unable to define the time that had elapsed from the moment of contact with the tick to the moment it was removed, and 105 (15.05%) did not provide an answer to the question. Subsequently, the patients were asked if they had noticed any symptoms after the tick bite. Of the patients, 278 (39.5%) reported redness that subsided after tick removal, and 118 (16.77%) reported redness at the site of the bite. Among other symptoms, 119 (16.9%) patients reported joint pain and swelling, and 17 (2.41%) reported nodular skin lesions. A total of 172 patients did not respond to the question (24.44%). Only 84 (12.36%) patients reported experiencing subjective flu-like symptoms after a tick bite, while 467 (66.34%) did not report these symptoms. Of the patients, 153 (21.73%) did not provide an answer. Among the patients who reported on the screening test, 66 (9.38%) indicated that they had a history of Lyme borreliosis, 505 (71.73%) denied having this disease, 56 (7.95%) responded that “it is hard to say”, and 77 (10.94%) did not provide an answer. Among the patients, 188 (26.70%) received antibiotic therapy, 362 (51.42%) were excluded from antibiotic therapy, and 154 (21.88%) did not respond. Of the 188 patients who received antibiotics, doxycycline (200 mg per day) was used as an antibiotic in 171 (91%) cases, and amoxicillin (3 g per day) was used in the remaining 17 (9%) cases.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE RESULTS OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE AND THE LEVEL OF ANTIBODIES DETERMINED USING ELISA AND WESTERN BLOT:

Statistically significant differences were not found in the distribution of single and multiple bites in the group of patients who reported a bite between positive and negative ELISA (χ2=0.17,

ANTIBODY TITERS IN THE IGG AND IGM CLASSES DETERMINED USING ELISA AND WESTERN BLOT METHODS:

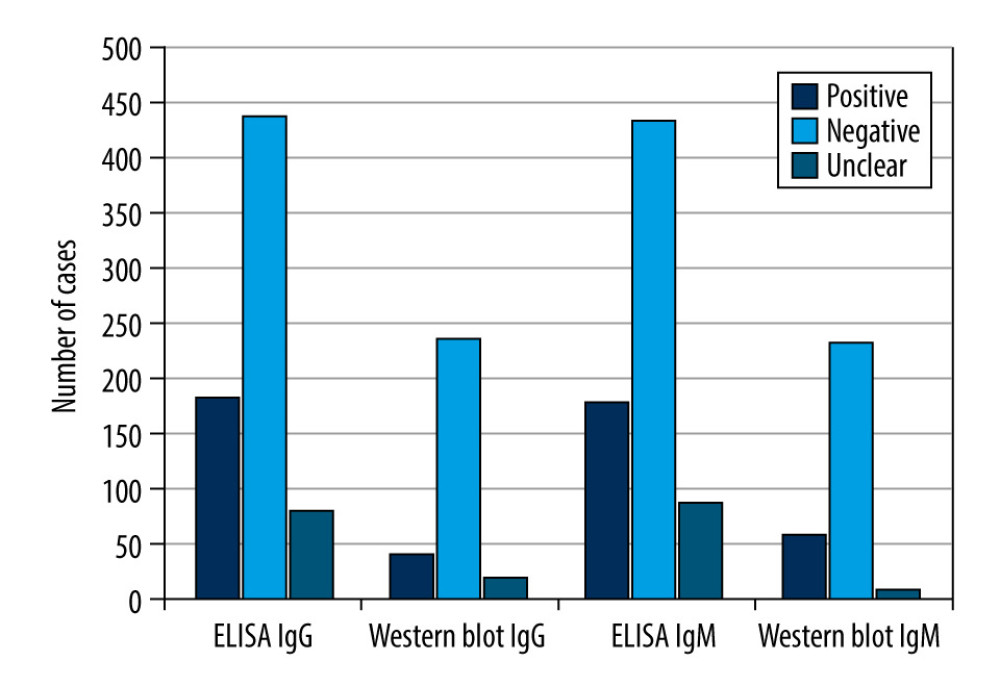

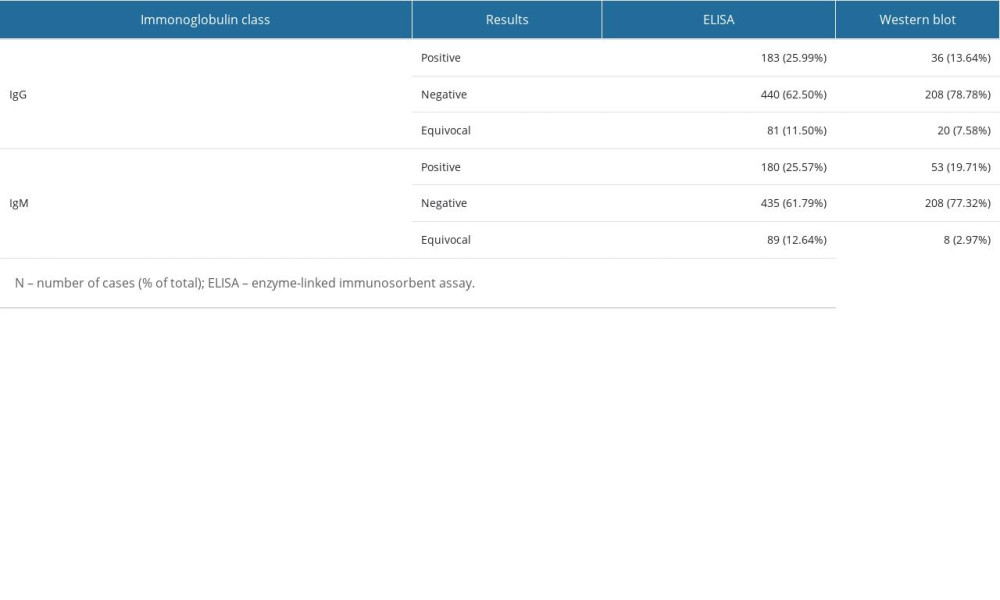

Regarding the ELISA test for the IgG immunoglobulin class, there were 183 (25.99%) positive results, 440 (62.5%) negative results, and 81 (11.5%) equivocal results. For the 264 patients with positive or equivocal results in the IgG immunoglobulin class, the results were validated using Western blot analysis, which showed 36 (13.64%) positive results, 208 (78.78%) negative results, and 20 (7.58%) equivocal results. Regarding IgM, the ELISA method showed 180 (25.57%) positive results, 435 (61.79%) negative results, and 89 (12.64%) equivocal results. For the 269 patients with positive or equivocal results in the IgM class, the results were validated using Western blot analysis, which showed 53 positive results (19.71%), 208 (77.32%) negative results, and 8 (2.97%) equivocal results.

Therefore, of the 264 samples in which the ELISA showed a positive or equivocal result in the IgG class, only 36 (13.64%) cases were confirmed to be B. burgdorferi sensu lato infections by Western blot analysis. In contrast, of the 269 cases in which a positive or equivocal result was obtained with ELISA in the IgM class, only 53 (19.70%) cases were confirmed to be B. burgdorferi sensu lato infections by Western blotting. Equivocal results in the Western blot test were obtained in <10% of all samples. Detailed results are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

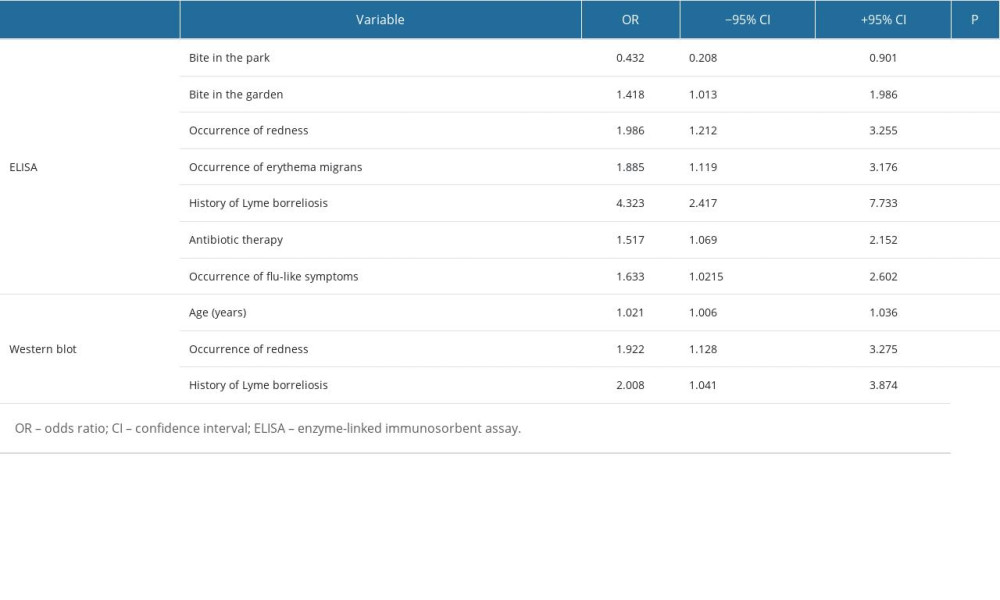

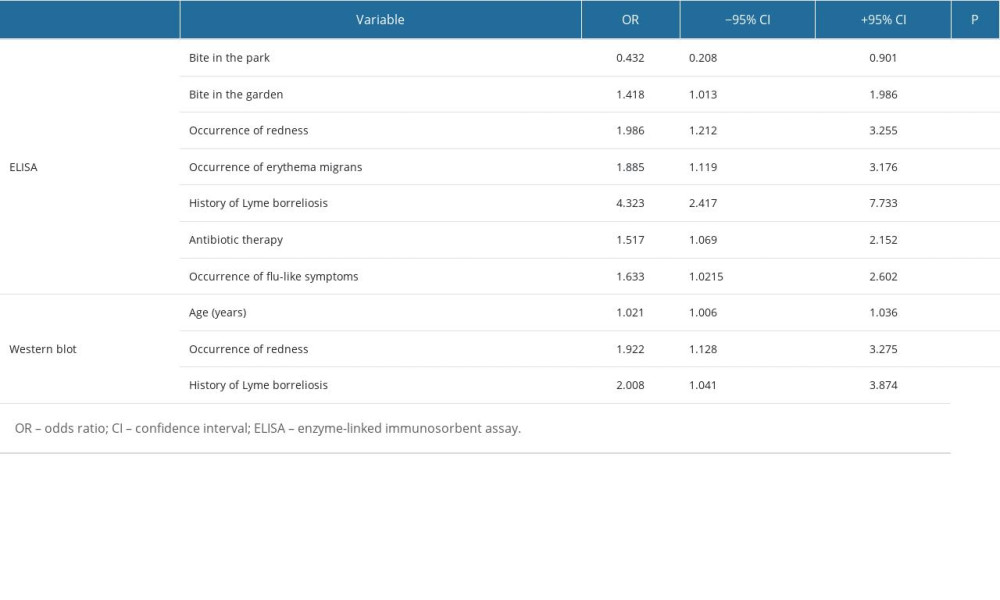

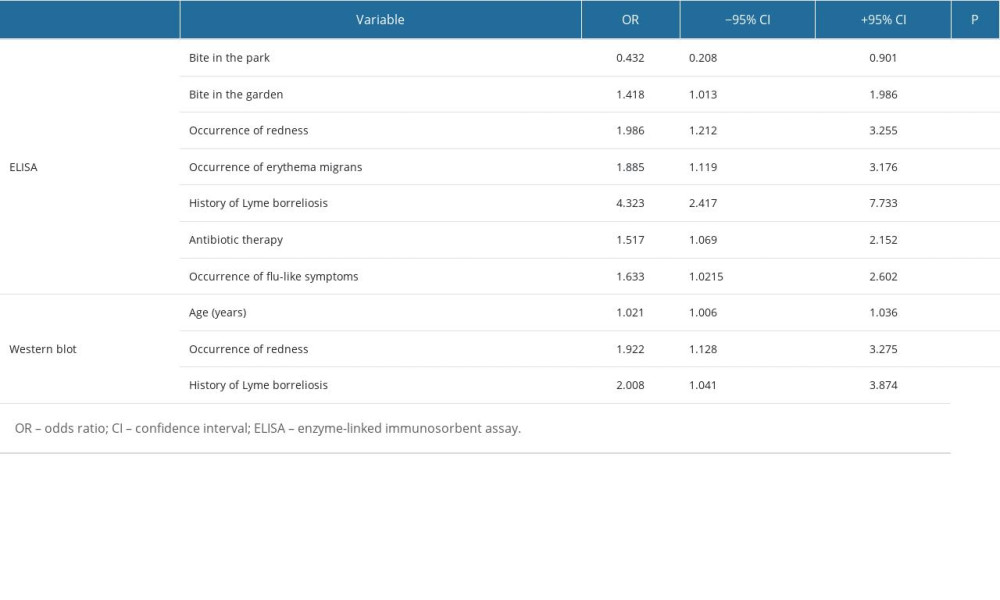

ANALYSIS OF THE RISK FACTORS FOR A POSITIVE RESULT IN THE ELISA AND WESTERN BLOT TESTS:

The logistic regression method significantly favored the occurrence of positive ELISA and Western blot test results (P<0.05). Regarding the ELISA test, the occurrence of a bite in a place other than the park and garden was associated with a more than 2-fold and almost 1.5-fold higher chance of positive ELISA results, respectively. The occurrence of redness and erythema at the bite site, use of antibiotics and occurrence of flu-like symptoms, and history of Lyme borreliosis were associated with an almost 2-fold, over 1.5-fold, and a 4-fold higher chance of obtaining a positive ELISA test result, respectively (Table 3).

The one-way logistic regression analysis in relation to the Western blot analysis is presented in Table 3. The occurrence of redness at the bite site and history of Lyme borreliosis increased the chance of occurrence of positive results on the Western blot test by approximately 2-fold. For each year of life, the chance of obtaining positive results also increased (Table 3).

:

Based on the available epidemiological data on the number of confirmed cases of B. burgdorferi sensu lato between 2016 and 2022, a systematic decrease in the number of cases in the Silesian province was observed. The most noticeable decrease in the number of cases was found between 2016 and 2017 and between 2019 and 2020. Furthermore, in 2021, we found a similar number of diagnoses as in the previous year. However, according to preliminary data for 2022, the number of confirmed cases of B. burgdorferi sensu lato compared with that of previous years (2020 and 2021) increased, reaching a level similar to that of 2019 (Table 4).

Regarding the epidemiological situation in Jaworzno itself, a significant decrease in the number of cases was found in 2020 compared with in the 2016–2019 period. Meanwhile, in 2021, the number of cases in Jaworzno was highest in the 2016–2022 period. Detailed epidemiological data on Lyme disease cases in the Silesian province and Jaworzno in 2016–2022 are presented in Table 4.

Discussion

Since 2002, an increasing number of cases of Lyme borreliosis have been reported in the Jaworzno area; therefore, in this study, we aimed to assess the frequency of the occurrence of antibodies against

A similarly designed study with a self-administered questionnaire and ELISA and Western blot testing was conducted by Panczuk et al in a group of 150 people, including 110 hunters and 40 people exposed to ticks for occupational reasons [17]. These authors noted a positive or equivocal ELISA result in 63.9% of the participants, and further Western blot analysis confirmed a positive or borderline result in at least 1 of the antibody classes in 38% of participants [17]. In our study, we recorded a lower percentage of positive/equivocal results, but this was due to the different populations included in the analysis.

The epidemiological data obtained indicated the need to perform screening tests in the entire population of the city to strengthen the diagnosis of

Based on epidemiological data for the period 2016–2022, it is worth highlighting the changes in the number of confirmed diagnoses of Lyme disease in Europe [13,27–33]. Of the tick population inhabiting the area of the Katowice Voivodeship (currently Silesian), 37.5% are carriers of Lyme borreliosis spirochetes [29,32].

Between 1990 and 1999, studies were conducted on the population of the common tick in Poland. The tick is the main vector for many pathogens that are dangerous to human health, including

Lyme borreliosis, which is diagnosed late and improperly treated, can have multiple consequences in the human body [34]; therefore, an accurate diagnosis based on epidemiological interviews, clinical pictures, a history of prior diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis, and positive results from ELISA and Western blot methods are important [35–37]. These methods constitute a reference diagnostic tool and should be used together with the obtained biological data [35–37]. Therefore, the screening tests conducted among the residents of the city of Jaworzno were accompanied by an information campaign aimed at increasing the awareness of medical personnel that the patient should be treated based on the whole picture, not just the serological test results. This is consistent with the study by Twizeyimana et al, who evaluated 253 blood samples using ELISA and Western blot tests between 2008 and 2012. In the IgG class, they found 187 positive and 66 equivocal results obtained using the ELISA test, which was confirmed using the Western blot test, with 50% positive results [38]. Meanwhile, in the IgM class, Twizeyimana et al obtained 94 positive and 40 equivocal results from 134 samples, which were then subjected to the Western blot test and obtained 18% positive results; they diagnosed various types of Lyme borreliosis in 75 of 2524 participants [38].

The ELISA test used for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis shows high sensitivity and low specificity, which can lead to false positive results [39,40]. Therefore, verification of the results obtained is necessary using the Western blot test, which has low sensitivity and high specificity. The 2-stage verification of the results increases the reliability of the diagnosis [41]. In the present study of 704 residents of Jaworzno, the use of the ELISA test resulted in 298 positive or equivocal results for IgM and/or IgG, which were verified using the Western blot test, and obtained 19.8% positive results in the IgM class and 13.8% positive results in the IgG class. Participants who reported tick bites, had clinical symptoms, and received antibiotic therapy showed statistically more frequent positive results in serological tests using ELISA and Western blot. A previous study conducted in the population of the southern regions of Poland that participated in the screening test for

Kubiak et al assessed 259 patients who were suspected of having Lyme disease and in whom IgG and IgM antibodies against specific

In conducting a large population-based study of 34157 patients (44861 serum samples), Westerholt et al assessed the prevalence of IgM and IgG antibodies to

There are some limitations to the present study. First, the questionnaire design presented limitations. We used a self-designed, not validated questionnaire. Not all study patients answered every question, which is a common risk of data obtained from questionnaires. It should also be considered that a survey participant might intentionally or mistakenly give an untruthful answer. Other limitations were the retrospective nature of the study and the number of study participants. Additionally, making a correct diagnosis and interpreting serological screening results for Lyme borreliosis are very difficult [45–48]. First, the multitude of

Conclusions

Among the 704 residents of Jaworzno, Poland, who participated in this study, the results of the immunoglobulin levels for both classes were not dependent on the age or sex of the patients. The ELISA method obtained similar values of positive, negative, and equivocal results in the serological testing. This was reflected in a survey conducted on patients who reported a tick bite and later received a positive result in the ELISA test as well as an approximate time between the infestation and removal of the tick. Although antibiotic therapy was introduced after the tick bite, the treated patients also obtained more positive results from the ELISA test. The occurrence of skin symptoms in the form of erythema migrants and a prior history of Lyme borreliosis diagnosis in the study group nearly doubled the chance of obtaining a positive result on the Western blot test.

It should be mentioned that the city of Jaworzno should be considered an endemic area for Lyme borreliosis. For this purpose, further faunal studies in this area are necessary. However, by comparing the epidemiological data obtained for the period 2016–2022 in Silesian province and Jaworzno with the global data, we observed an increase in the number of Lyme disease case diagnoses [23,24,57]. Therefore, it is reasonable to develop new, up-to-date guidelines for actions taken within the framework of health policy to develop forecasts of the risk of Lyme disease for the city of Jaworzno.

Tables

Table 1. Questions on questionnaire asked of survey participants. Table 2. Assessment of conformity between the results of immunoglobulin IgM and IgG determination using ELISA and Western blot testing.

Table 2. Assessment of conformity between the results of immunoglobulin IgM and IgG determination using ELISA and Western blot testing. Table 3. Statistically significant results of one-way logistic regression analysis of the occurrence of positive results in the ELISA and Western blot tests, considering variables based on the survey results.

Table 3. Statistically significant results of one-way logistic regression analysis of the occurrence of positive results in the ELISA and Western blot tests, considering variables based on the survey results. Table 4. Epidemiological analysis of confirmed diagnoses of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the Silesian Voivodeship and Jaworzno between 2016 and 2022.

Table 4. Epidemiological analysis of confirmed diagnoses of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the Silesian Voivodeship and Jaworzno between 2016 and 2022.

References

1. Kugeler KJ, Schwartz AM, Delorey MJ, Estimating the frequency of Lyme disease diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018: Emerg Infect Dis, 2021; 27(2); 616-19

2. Stanek G, Strle F, Lyme borreliosis-from tick bite to diagnosis and treatment: FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2018; 42(3); 233-58

3. Steere AC, Strle F, Wormser GP, Lyme borreliosis: Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016; 2; 16090 [Erratum in: Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17062]

4. Smoleńska Z, Matyjasek A, Zdrojewski Z, Borelioza – najnowsze rekomendacje w diagnostyce i leczeniu: Rheumatol Forum, 2016; 2(2); 58-64 [in Polish]

5. Skar GL, Simonsen KA, Lyme disease. [Updated 2023 Dec 4[: StatPearls [Internet[, 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431066/

6. Tatum R, Pearson-Shaver AL, Borrelia burgdorferi. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]: StatPearls [Internet], 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532894/

7. Colby E, Olsen J, Angulo FJ, Estimated incidence of symptomatic Lyme borreliosis cases in Lublin, Poland in 2021: Microorganisms, 2023; 11(10); 2481

8. Paradowska-Stankiewicz I, Chrześcijańska I, Lyme disease in Poland in 2012: Przegl Epidemiol, 2014; 68(2); 275-77

9. Andreychyn M, Pańczuk A, Shkilna M, Epidemiological situation of Lyme borreliosis and diagnosis standards in Poland and Ukraine: Health Probl Civiliz, 2017; 11(3); 190-94

10. Paradowska-Stankiewicz I, Zbrzeźniak J, Skufca J, A Retrospective database study of Lyme borreliosis incidence in Poland from 2015 to 2019: A public health concern: Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2023; 23(4); 247-55

11. Zbrzeźniak J, Paradowska-Stankiewicz I, Lyme disease in Poland in 2020: Przegl Epidemiol, 2022; 76(3); pe.76.36

12. Hoeve-Bakker BJA, Jonker M, Brandenburg AH, The performance of nine commercial serological screening assays for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: A multicenter modified two-gate design study: Microbiol Spectr, 2022; 10(2); e0051022

13. Cisak E, Wójcik-Fatla A, Zając V, Risk of Lyme disease at various sites and workplaces of forestry workers in eastern Poland: Ann Agric Environ Med, 2012; 19(3); 465-68

14. : Statystyczne Vademecum samorządowca 2020 Available from: [in Polish]https://katowice.stat.gov.pl/vademecum/vademecum_slaskie/portrety_miast/miasto_jaworzno.pdf

15. : Kalkulator doboru próby Available from: [in Polish]https://www.naukowiec.org/dobor.html

16. Brzozowska M, Wierzba A, Śliwczyński A, The problem of Lyme borreliosis infections in urban and rural residents in Poland, based on National Health Fund data: Ann Agric Environ Med, 2021; 28(2); 277-82

17. Pańczuk A, Tokarska-Rodak M, Plewik D, Paszkiewicz J, Tick exposure and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies among hunters and other individuals exposed to vector ticks in eastern Poland: Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig, 2019; 70(2); 161-68

18. : Lyme disease, National Institute for Health and care excellence Available from:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng95/resources/lyme-disease-pdf-1837756839877

19. Whaley CM, Pera MF, Cantor J, Changes in health services use among commercially insured US populations during the COVID-19 pandemic: JAMA Netw Open, 2020; 3(11); e2024984

20. Blumenthal D, Fowler EJ, Abrams M, Collins SR, COVID-19 – implications for the health care system: N Engl J Med, 2020; 383(15); 1483-88 [Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2020;383(17):1698]

21. Liu Q, Xu K, Wang X, Wang W, From SARS to COVID-19: What lessons have we learned?: J Infect Public Health, 2020; 13(11); 1611-18

22. Johnson LB, Maloney EL, Access to care in Lyme disease: Clinician barriers to providing care: Healthcare (Basel), 2022; 10(10); 1882

23. Ogden NH, Bouchard C, Badcock J, What is the real number of Lyme disease cases in Canada?: BMC Public Health, 2019; 19(1); 849

24. Sykes RA, Makiello P, An estimate of Lyme borreliosis incidence in Western Europe: J Public Health (Oxf), 2017; 39(1); 74-81

25. Ermenlieva N, Tsankova G, Todorova TT, Epidemiological study of Lyme disease in Bulgaria: Cent Eur J Public Health, 2019; 27(3); 235-38

26. Hofhuis A, Harms M, Bennema S, Physician reported incidence of early and late Lyme borreliosis: Parasit Vectors, 2015; 8; 161 [Erratum in: Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:378]

27. Nowak-Chmura M, A biological/medical review of alien tick species (Acari: Ixodida) accidentally transferred to Poland: Ann Parasitol, 2014; 60(1); 49-59

28. Zygner W, Gójska-Zygner O, Bartosik J, Canine babesiosis caused by large babesia species: Global prevalence and risk factors – a review: Animals (Basel), 2023; 13(16); 2612

29. Stańczak J, Racewicz M, Kubica-Biernat B: Ann Agric Environ Med, 1999; 6(2); 127-32

30. Mihaljica D, Marković D, Radulović Ž: Exp Appl Acarol, 2017; 72(4); 429-37

31. Schubert F, Pålsson K, Santangelo E, Borg-Karlson AK, Sulfate turpentine: A resource of tick repellent compounds: Exp Appl Acarol, 2017; 72(3); 291-302

32. Strzelczyk JK, Gaździcka J, Cuber P: Acta Parasitol, 2015; 60(4); 666-74

33. Venclíková K, Betášová L, Sikutová S: Acta Parasitol, 2014; 59(4); 717-20

34. Maroszyńska-Dmoch E, Wożakowska-Kapłon B, Borelioza z Lyme – niedoceniany problem w praktyce kardiologa: Folia Cardiol, 2008; 3(8–9); 375-82 [in Polish]

35. Eldin C, Raffetin A, Bouiller K, Review of European and American guidelines for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: Med Mal Infect, 2019; 49(2); 121-32

36. Branda JA, Steere AC, Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: Clin Microbiol Rev, 2021; 34(2); e00018-19

37. Kullberg BJ, Vrijmoeth HD, van de Schoor F, Hovius JW, Lyme borreliosis: Diagnosis and management: BMJ, 2020; 369; m1041

38. Twizeyimana E, Pichard E, Lunel-Fabiani F, Impact of serodiagnosis on the management of Lyme borreliosis at Angers University Hospital: Med Mal Infect, 2014; 44(9); 429-32

39. Talagrand-Reboul E, Raffetin A, Zachary P, Immunoserological diagnosis of human borrelioses: Current knowledge and perspectives: Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2020; 10; 241

40. Eldin C, Jaulhac B, Mediannikov O, Values of diagnostic tests for the various species of spirochetes: Med Mal Infect, 2019; 49(2); 102-11

41. Noworyta J, Machcińska M, Brasse-Rumin M, Western blot method as a necessary step of serodiagnostics of Lyme disease: Reumatologia/Rheumatology, 2012; 50(5); 397-402

42. Zalewska‐Ziob M, Adamek B, Strzelczyk JK: Pediatr Med Rodz, 2012; 1(8); 40-45 [in Polish]

43. Kubiak K, Dzika E, Równiak J: Ann Agric Environ Med, 2012; 19(2); 203-7

44. Westerholt M, Krogfelt KA, Dessau RB, Ocias LF: Clin Microbiol Infect, 2023; 29(12); 1561-66

45. Cisak E, Chmielewska-Badora J, Zwoliński J, Characteristics of Western blot tests applied in borelliosis diagnotics in humans: Med Ogólna Nauki O Zdrowiu, 2009; 15(4); 514-25

46. Wojciechowska-Koszko I, Kwiatkowski P, Sienkiewicz M, Cross-reactive results in serological tests for borreliosis in patients with active viral infections: Pathogens, 2022; 11(2); 203

47. Kmieciak W, Ciszewski M, Szewczyk EMTick-borne diseases in Poland: Prevalence and difficulties in diagnostics: Med Pr, 2016; 67(1); 73-87 [in Polish]

48. Stefanoff P, Rosińska M, Zieliński AEpidemiology of tick-borne diseases in Poland, Epidemiologia chorób przenoszonych przez kleszcze w Polsce: Przegl Epidemiol, 2006; 60(Suppl 1); 151-59 [in Polish]

49. Robertson J, Guy E, Andrews N, A European multicenter study of immunoblotting in serodiagnosis of lyme borreliosis: J Clin Microbiol, 2000; 38(6); 2097-102

50. Wozińska-Klepadło M, Toczyłowski K, Sulik A, Challenges and new methods in the diagnosis of Lyme disease in children: Przegl Epidemiol, 2020; 74(4); 652-61

51. Grąźlewska W, Holec-Gąsior L, Recombinant antigens in serological diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: Postępy Mikrobiol – Adv Microbiol, 2019; 58(4); 399-413

52. Leeflang MM, Ang CW, Berkhout J, The diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for Lyme borreliosis in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis: BMC Infect Dis, 2016; 16; 140

53. Wojciechowska-Koszko I, Mnichowska-Polanowska M, Serologiczna diagnostyka boreliozy z Lyme w praktyce laboratoryjnej: Post Mikrobiol, 2015; 54(3); 283-90 [in Polish]

54. Asman M, Witecka J, Solarz K: Ann Agric Environ Med, 2019; 26(4); 544-47

55. Rauter C, Hartung T: Appl Environ Microbiol, 2005; 71(11); 7203-16

56. Wójcik-Fatla A, Szymańska J, Wdowiak L: Ann Agric Environ Med, 2009; 16(1); 151-58

57. Rogalska AM, Pawełczyk O, Solarz K, Holecki T, What are the costs of diagnostics and treatment of Lyme borreliosis in Poland?: Front Public Health, 2021; 8; 599239

Figures

Tables

Table 1. Questions on questionnaire asked of survey participants.

Table 1. Questions on questionnaire asked of survey participants. Table 2. Assessment of conformity between the results of immunoglobulin IgM and IgG determination using ELISA and Western blot testing.

Table 2. Assessment of conformity between the results of immunoglobulin IgM and IgG determination using ELISA and Western blot testing. Table 3. Statistically significant results of one-way logistic regression analysis of the occurrence of positive results in the ELISA and Western blot tests, considering variables based on the survey results.

Table 3. Statistically significant results of one-way logistic regression analysis of the occurrence of positive results in the ELISA and Western blot tests, considering variables based on the survey results. Table 4. Epidemiological analysis of confirmed diagnoses of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the Silesian Voivodeship and Jaworzno between 2016 and 2022.

Table 4. Epidemiological analysis of confirmed diagnoses of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the Silesian Voivodeship and Jaworzno between 2016 and 2022. Table 1. Questions on questionnaire asked of survey participants.

Table 1. Questions on questionnaire asked of survey participants. Table 2. Assessment of conformity between the results of immunoglobulin IgM and IgG determination using ELISA and Western blot testing.

Table 2. Assessment of conformity between the results of immunoglobulin IgM and IgG determination using ELISA and Western blot testing. Table 3. Statistically significant results of one-way logistic regression analysis of the occurrence of positive results in the ELISA and Western blot tests, considering variables based on the survey results.

Table 3. Statistically significant results of one-way logistic regression analysis of the occurrence of positive results in the ELISA and Western blot tests, considering variables based on the survey results. Table 4. Epidemiological analysis of confirmed diagnoses of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the Silesian Voivodeship and Jaworzno between 2016 and 2022.

Table 4. Epidemiological analysis of confirmed diagnoses of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the Silesian Voivodeship and Jaworzno between 2016 and 2022. In Press

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952