16 February 2024: Clinical Research

Factors Influencing Discontinuation of Clazosentan Therapy in Elderly Patients with Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Retrospective Study from a Japanese Single Center

Tatsushi MutohDOI: 10.12659/MSM.943303

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e943303

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Clazosentan is an endothelin receptor antagonist approved in Japan for preventing cerebral vasospasm and vasospasm-associated cerebral ischemia and infarction. This study included elderly patients aged ≥75 years with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and aimed to evaluate the factors associated with discontinuing anti-vasospasm therapy with clazosentan.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: In this single-center retrospective observational study, we extracted diagnostic and therapeutic work-up data of consecutive 40 patients with SAH treated with clazosentan infusion (10 mg/h) as first-line anti-vasospasm therapy between May 2022 and August 2023. Patient data were compared between the discontinued and completed groups, and related factors for the discontinuation were further analyzed.

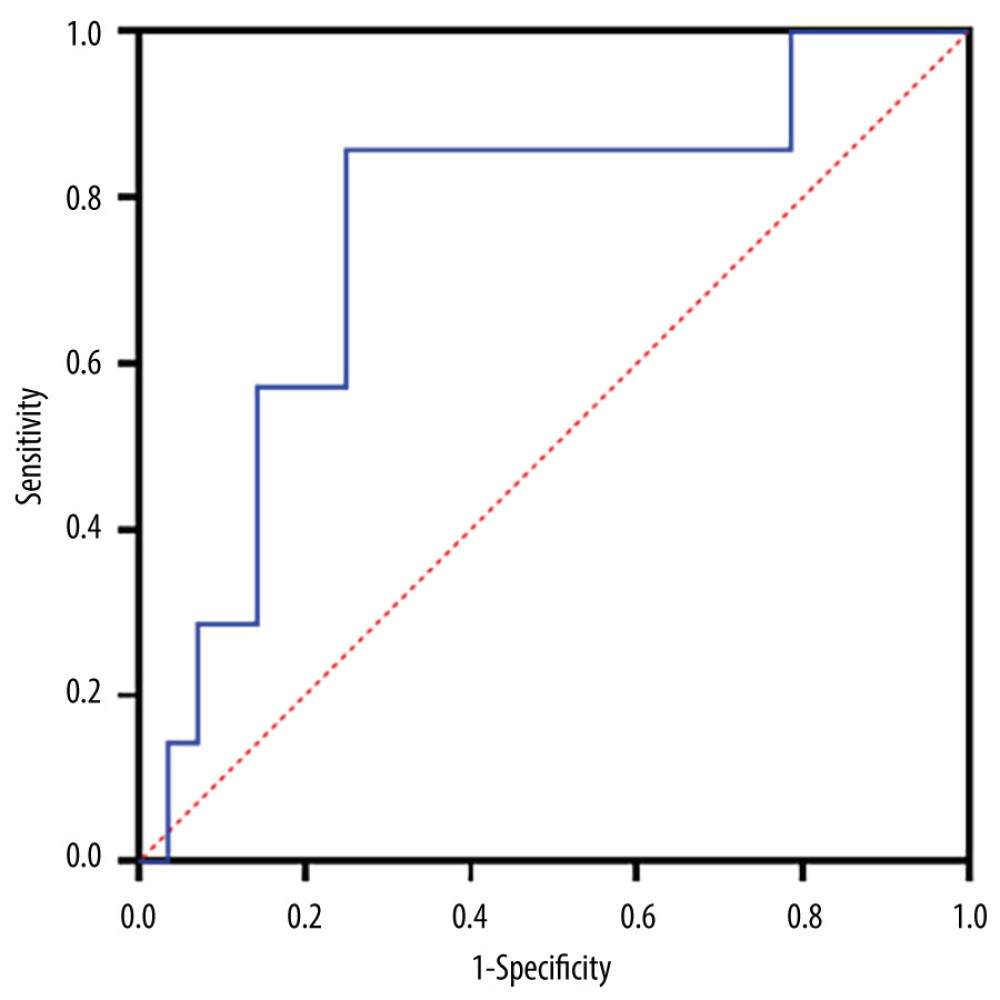

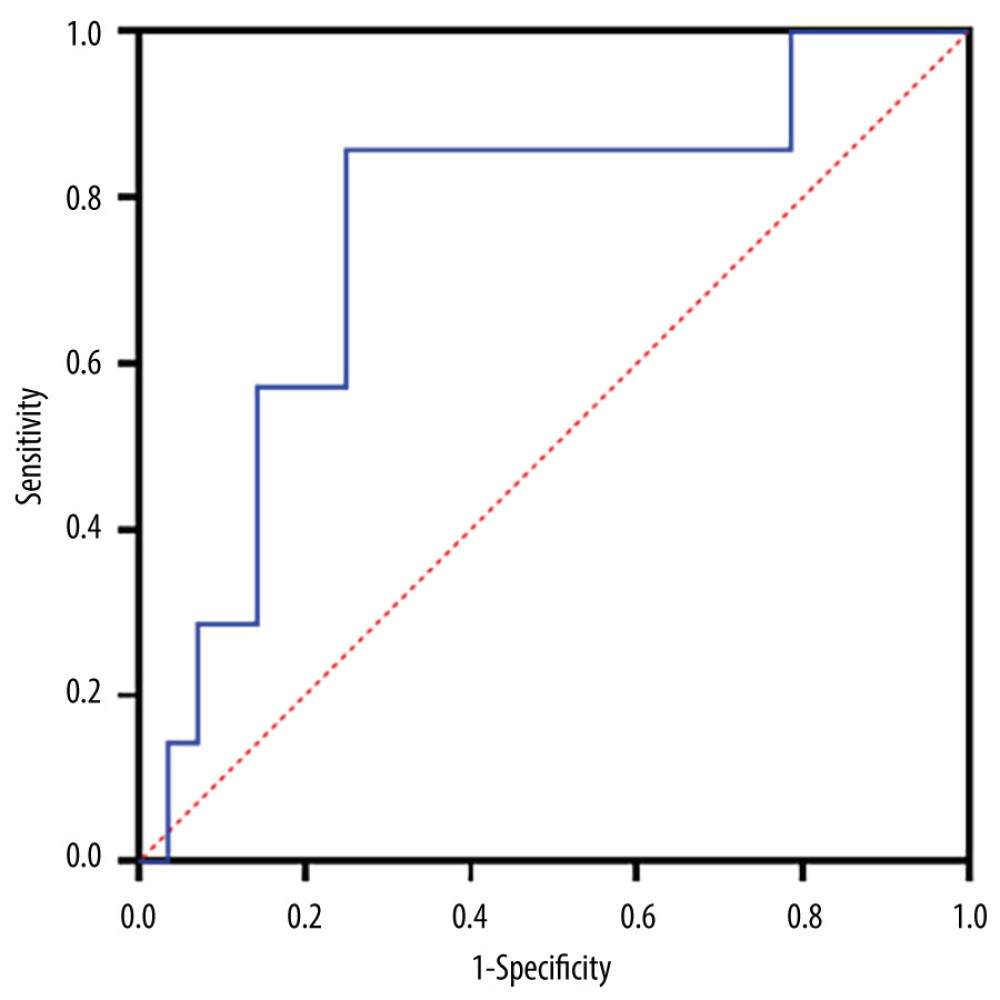

RESULTS: Clazosentan was discontinued in 22% (n=9) of patients due to intolerable dyspnea accompanied by hypoxemia at 5±3 days after therapy initiation, in which 44% (n=4) were elderly (≥75 years). Patients who discontinued clazosentan therapy showed significantly lower urine volumes compared with those who completed the therapy (P<0.05). Multivariate regression analysis revealed that day-to-day urine volume variance and older age were independent risk factors for drug cessation (P<0.05). The cut-off value for predicting clazosentan discontinuation was -0.7 mL/kg/h with sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 75% (area under the curve: 0.76±0.10; 95% confidence interval: 0.56-0.96; P=0.035).

CONCLUSIONS: Our results suggest that approximately 20% of SAH patients suffered from intolerable respiratory symptoms attributable to hypoxemia. We found that both reduced day-to-day urine volume variation and older age are independent risk factors for drug discontinuation.

Keywords: Clazosentan, Frail Elderly, Risk Factors, Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, Vasospasm, Intracranial

Background

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is one of the most striking and devastating neurological disorders [1]. SAH affects most central nervous system dysfunctions, leading to deleterious systemic consequences such as takotsubo cardiomyopathy and neurogenic pulmonary edema [2]. Previous studies have suggested that severe hypoxemia due to acute post-SAH pulmonary edema can lead to a global decrease in cerebral perfusion and ischemia, thereby complicating intensive fluid management [3]. More importantly, cerebral vasospasm is the key factor contributing to development of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) within 2 weeks of ictus, thus requiring prompt treatment to avoid brain infarction and related poor outcomes.

Despite the study of many pharmacological therapies for the prevention of post-SAH DCI, a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, nimodipine, remains the only drug universally recommended in this patient population [4]. Clazosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, investigated for use in a novel pharmacological prevention strategy of DCI in SAH [5–8], reduced cerebral vasospasm incidence and related morbidity at 6 weeks after SAH in phase 3 trials [9]. This led to its initial approval for clinical use in Japan in April 2022 [10]. Although prior studies have described the efficacy and safety profile of clazosentan (ie, it is well tolerated, but is associated with an increased rate of lung complications, anemia, and hypotension) [11], clinical data regarding serious systemic events necessitating therapy discontinuation and/or additional rescue therapy are limited. In this study, we focused on overall analysis of consecutive patients, including elderly adults aged 75 years and older, because no clinical data across the age boundaries (eg, comparison between elderly [≥75 years] and younger [<75 years] patients) are available.

Basically, older patients are more prone to brain vulnerability than younger adults due to underlying age-related comorbidities and high risk of systemic complications [12]. It has also been recognized that advanced age is a poor prognostic factor in patients after SAH [13]. In fact, in the post-approval clinical setting, we sometimes experience severe intrathoracic complications (eg, severe pleural effusion and pulmonary congestion/edema) concomitant with hypoxemia and reduced urinary output that may present dyspnea, after application of clazosentan as a first-line anti-vasospasm therapy in elderly SAH patients. However, only a few small studies have analyzed the effect of clazosentan in elderly patients, in which no statistically significant differences were detected from younger (age <75 years) patients [14]. Therefore, this retrospective study included patients aged ≥75 years with aneurysmal SAH to evaluate the factors associated with discontinuing anti-vasospasm therapy with clazosentan.

Material and Methods

ETHICS APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT:

This retrospective analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee of Akita Cerebrospinal and Cardiovascular Center (approval number: 23–14) and all procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Comprehensive informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parental guardians on admission.

STUDY DESIGN:

We retrospectively reviewed data of consecutive patients treated with clazosentan as first-line anti-vasospasm therapy following aneurysmal SAH at the Akita Cerebrospinal and Cardiovascular Center between May 2022 and August 2023. In all of the patient records, SAH was diagnosed on admission based on clinical findings and results from non-contrast computed tomography (CT) examinations followed by exploring the location of ruptured aneurysms using contrast-enhanced CT angiography of the brain.

CLAZOSENTAN-BASED ANTI-VASOSPASM THERAPY:

Per the manufacturer’s instructions, all patients received clazosentan as a continuous intravenous infusion at 10 mg/h, starting within 48 hours postoperatively after SAH (onset; designated as day 0) for up to 14 days, with a minimum of 10 days. Vasodilatory and/or antiplatelet agents such as nimodipine (not approved in Japan), fasudil hydrochloride, or cilostazol were not used. Levetiracetam (1000 mg/day) was administered for preventing postoperative epilepsy. Intracranial pressure was controlled within normal range by cisternal, ventricular, or cerebrospinal drainage, as necessary. Hyponatremia (serum sodium level of <130 mEq/L) or hypokalemia (serum potassium level of <3.0 mEq/L) was corrected by adding ampule(s) of each electrode solution (10 mL of 10%NaCl or K+ 10 mEq) to the main fluid bag. If hyponatremia persisted, fludrocortisone (0.1 mg/d) was given. Blood transfusion was performed only when the hematocrit level was <30%. If the maximal systolic blood pressure was >180 mmHg, a calcium antagonist was administered. For adverse cardiopulmonary events nonresponsive to standard medical care within 48 hours, clazosentan was discontinued and switched further to rescue therapy, including dobutamine-induced hyperdynamic and/or endovascular therapy (intraarterial fasudil and/or percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty) [15,16], until symptom resolution.

MEASUREMENTS:

The primary outcome was discontinuation of clazosentan therapy. Demographic, clinical, and radiological data were compared between patients with completed and those with discontinued clazosentan therapy. Treatment-necessitating serious adverse events were documented. Therapy was discontinued upon symptomatic adverse event onset (eg, hypoxemia [defined by peripheral oxygen saturation <90% or partial arterial oxygen pressure <60 Torr] and hypotension and hypotension [systolic blood pressure ≤90 mmHg]) or due to lack of efficacy (disease progression requiring rescue therapy). Along with routine hemodynamic monitoring and laboratory/neurological exams, body weight, urine volume, and fluid balance were measured daily. In addition to an arterial blood gas exam, we also performed chest X-ray, head CT, and echocardiography when cardiorespiratory insufficiency was suspected. Secondary outcomes included occurrence of DCI and 90-day functional outcome. Evaluation for radiological vasospasm and DCI (newly-developed infarction) was performed by CT angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, and/or diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging on days 5–7 and 14–16 after SAH. Ninety-day functional outcomes were determined based on modified Rankin scale (mRS) scores (good: 0–2; poor 3–6).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Data were checked for normal distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired

Results

CLINICAL DATA:

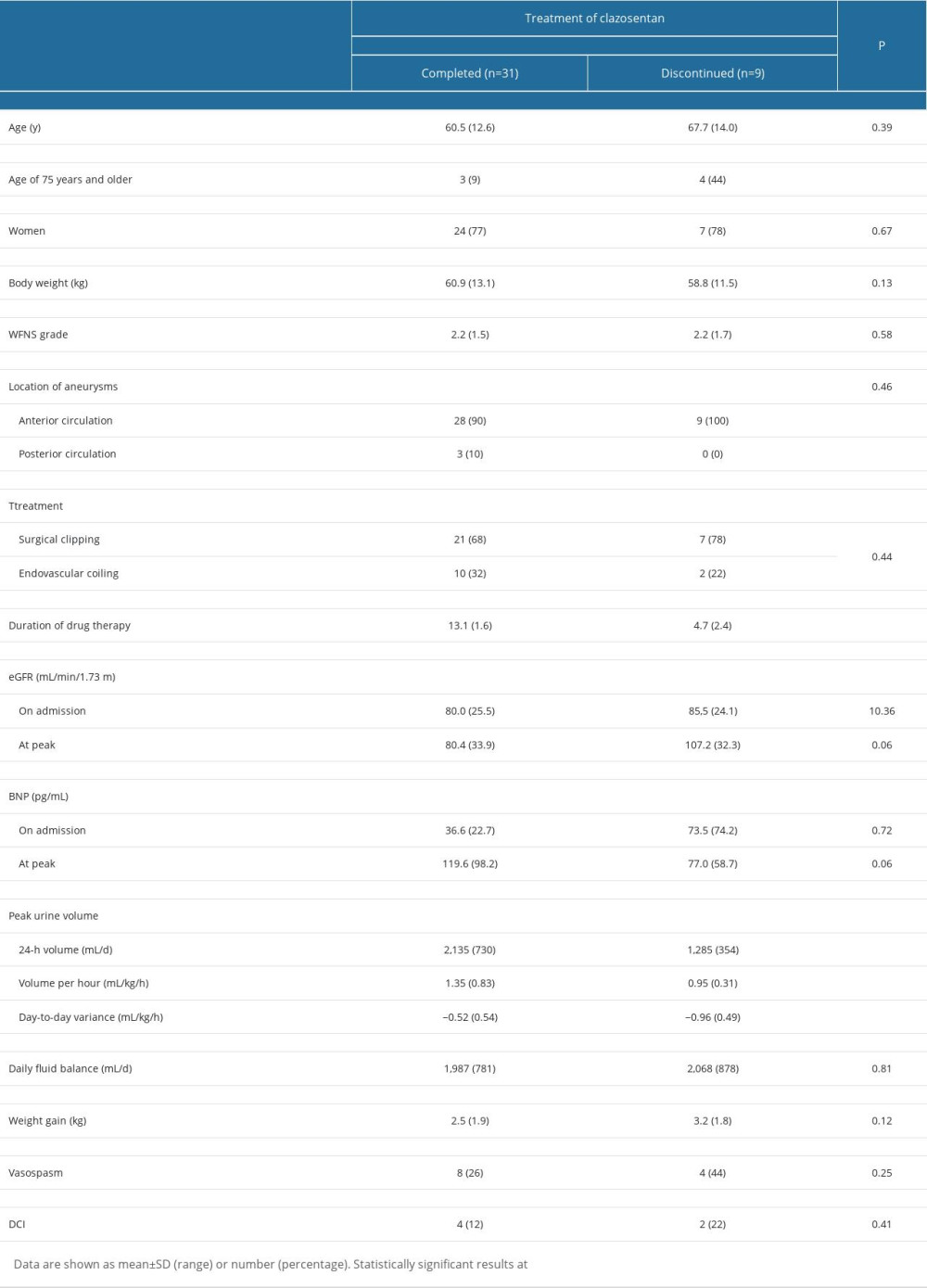

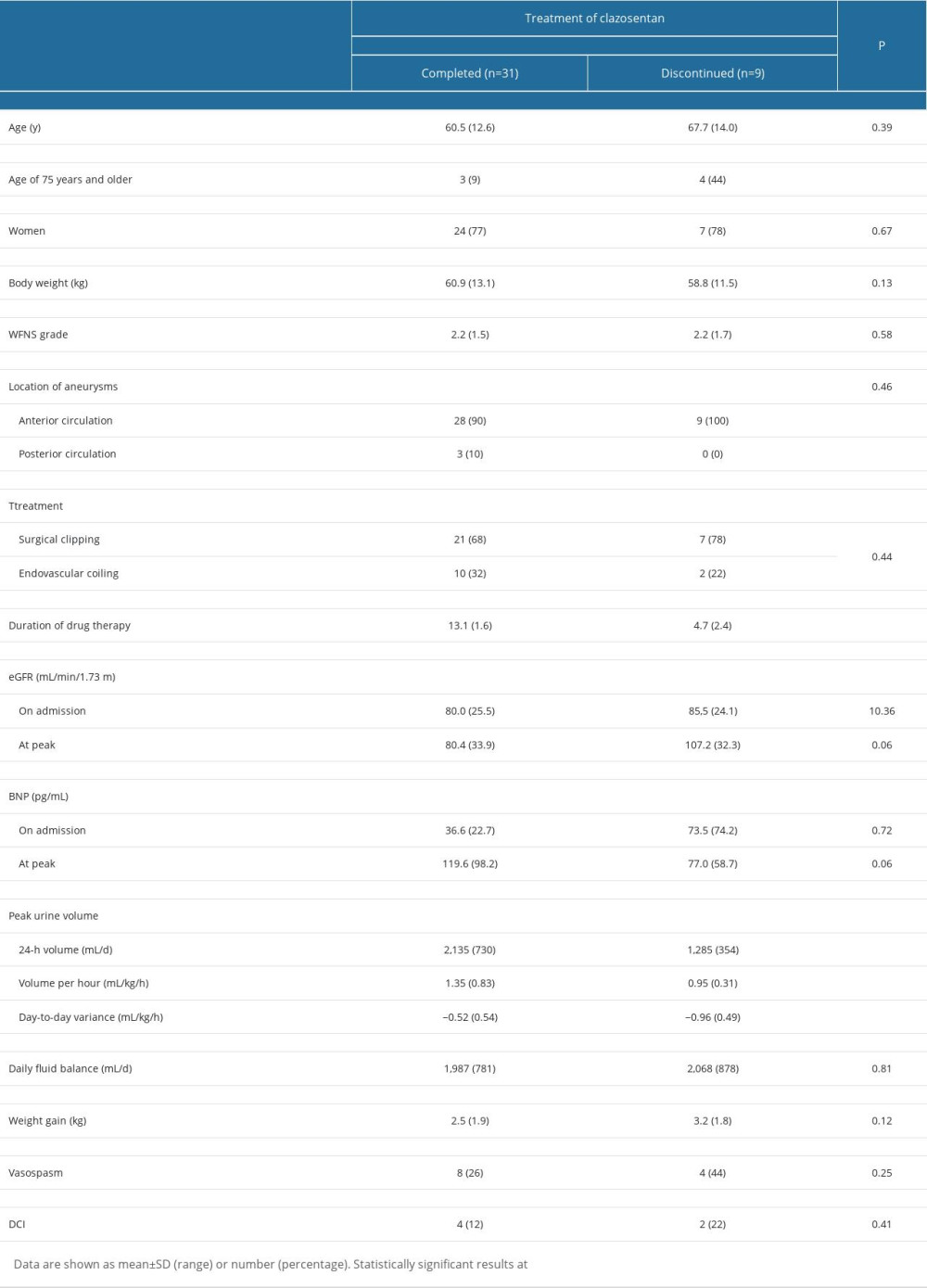

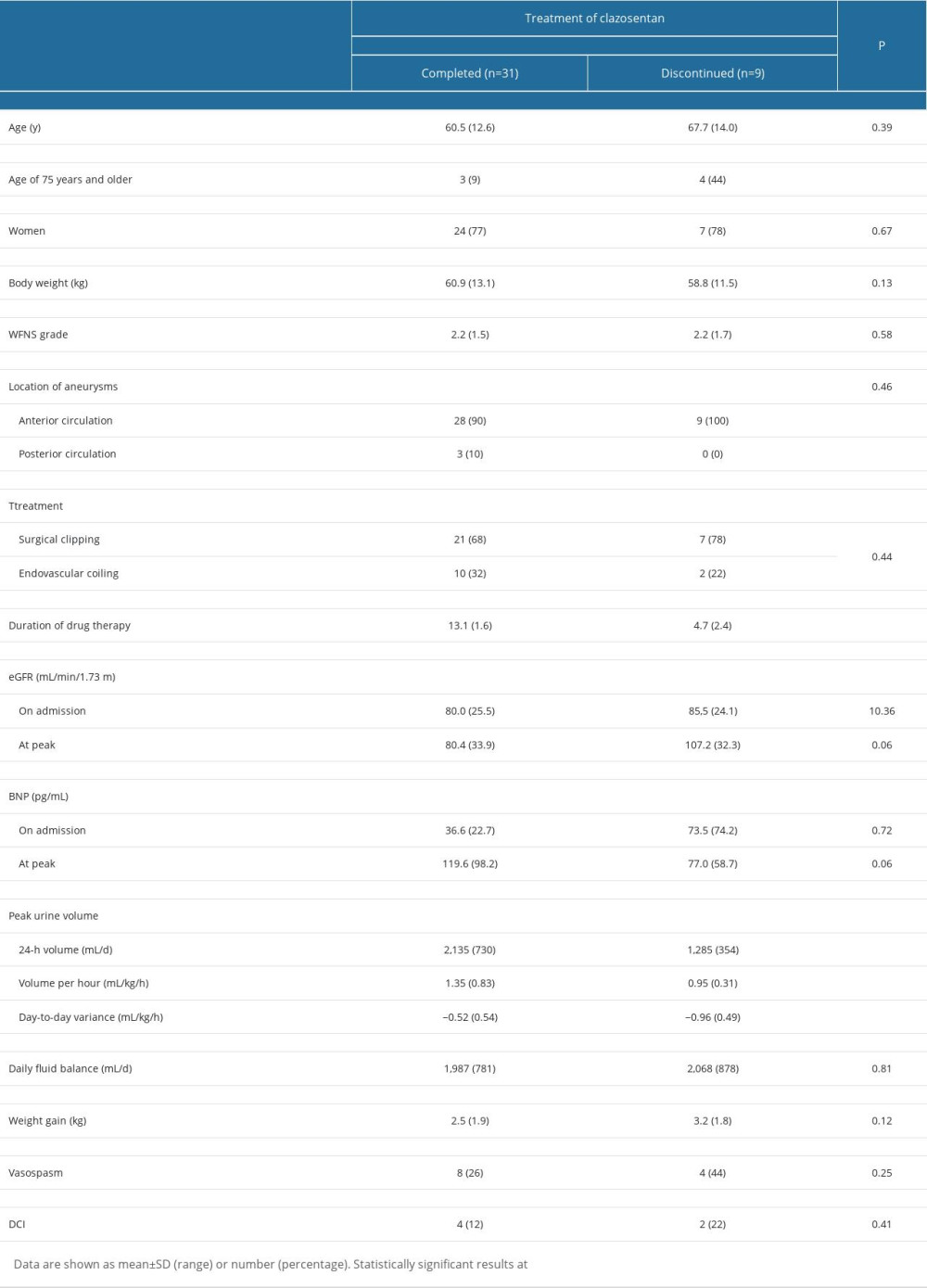

The clinical characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. Among 40 patients, clazosentan was discontinued in 9 (22%) patients due to intolerable dyspnea accompanied by hypoxemia and pleural effusion with or without hypotension at 5±3 days after therapy initiation, despite no obvious previous cardiorespiratory abnormalities. All patients underwent successful aneurysm obliteration under general anesthesia within 48 hours of SAH ictus, and there were no perioperative systemic complications. In our series, discontinuation of clazosentan did not affect occurrence of DCI or 90-day functional outcomes (P>0.05 compared with patients who completed the therapy).

CASE PRESENTATION:

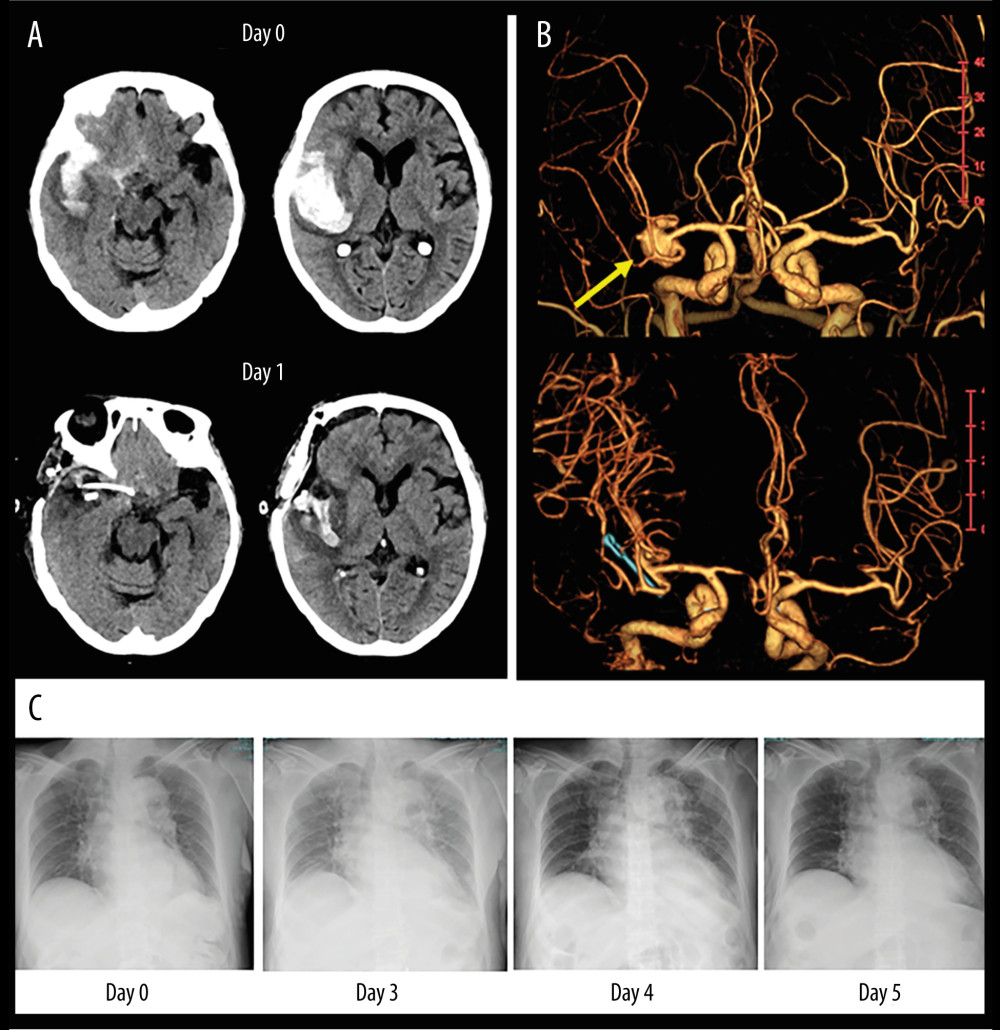

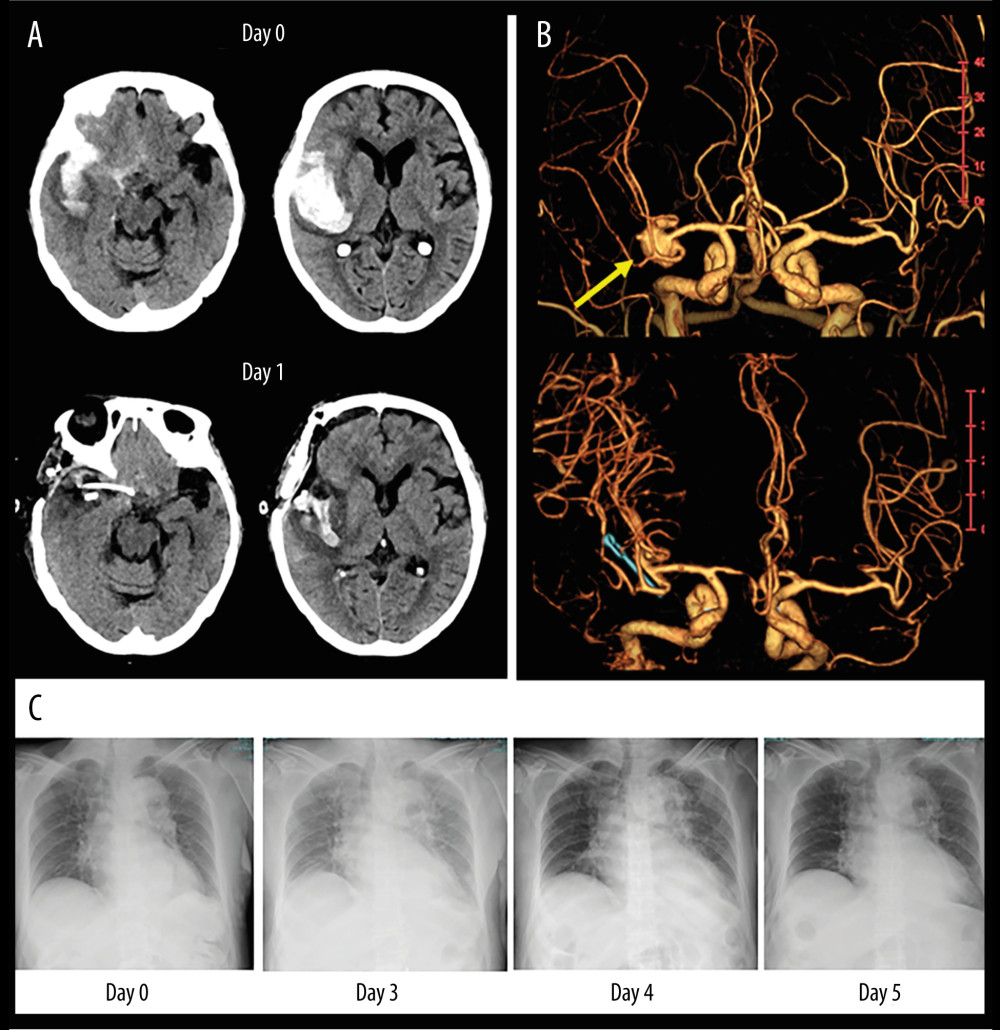

An 81-year-old woman was admitted to the Emergency Department with a chief concern of headache followed by loss of consciousness and left hemiparesis. On admission, non-contrast computed tomography (CT), as a routine diagnostic imaging exam, revealed SAH combined with right intrasylvian hematoma (Figure 1A). Subsequent volume-rendering CT angiography imaging shows a large aneurysm in the right middle cerebral artery (Figure 1B) compatible with the clot distribution. After surgical clipping of the aneurysm and hematoma evacuation, she gradually became alert without motor deficits. Postoperative medical management was started, including clazosentan therapy. Although she had no remarkable findings suggestive of vasospasm and related DCI, her urine volume declined after day 2, with increasing body weight and shortness of breath. Despite fluid titration including reduction of fluid infusion rates and administration of furosemide, we had to discontinue clazosentan infusion due to symptomatic hypoxemia and rapidly progressive pulmonary edema detected on day 3 (Figure 1C). She recovered gradually over the next 2 days after drug discontinuation, and was transferred 3 months later to a nursing home with a modified Rankin score (mRS) of 2.

FACTOR ANALYSIS FOR DRUG DISCONTINUATION:

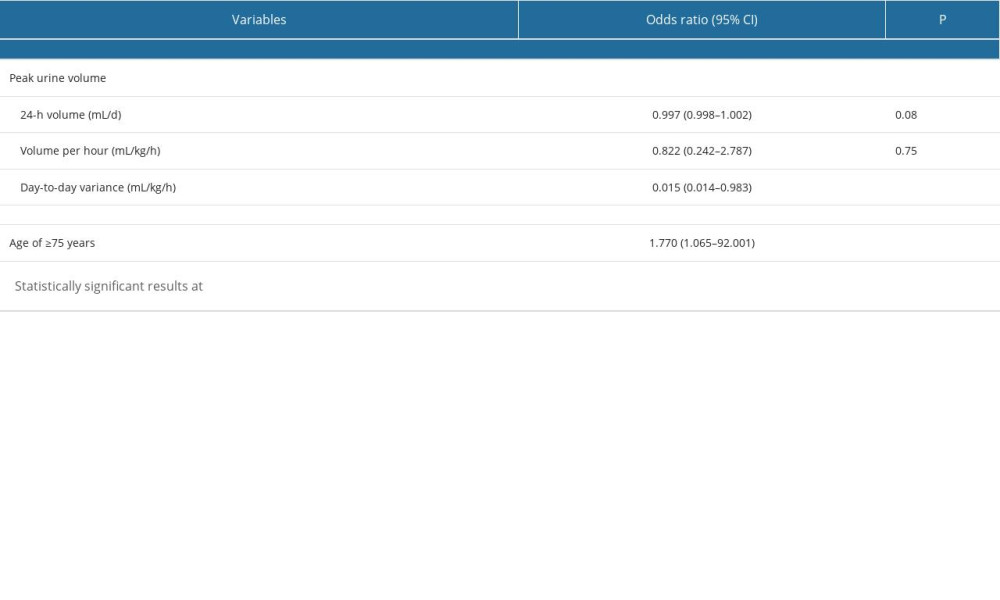

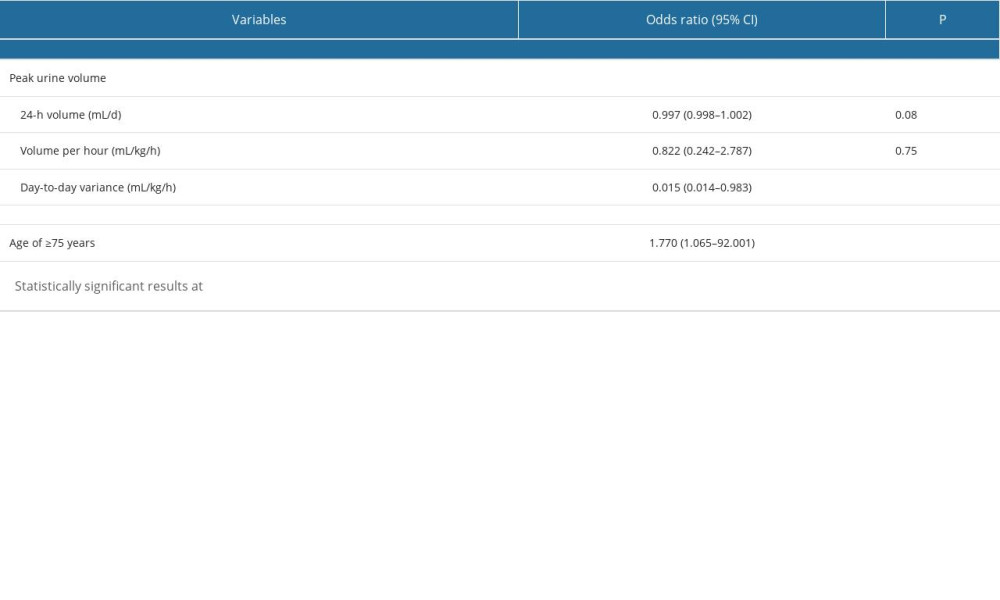

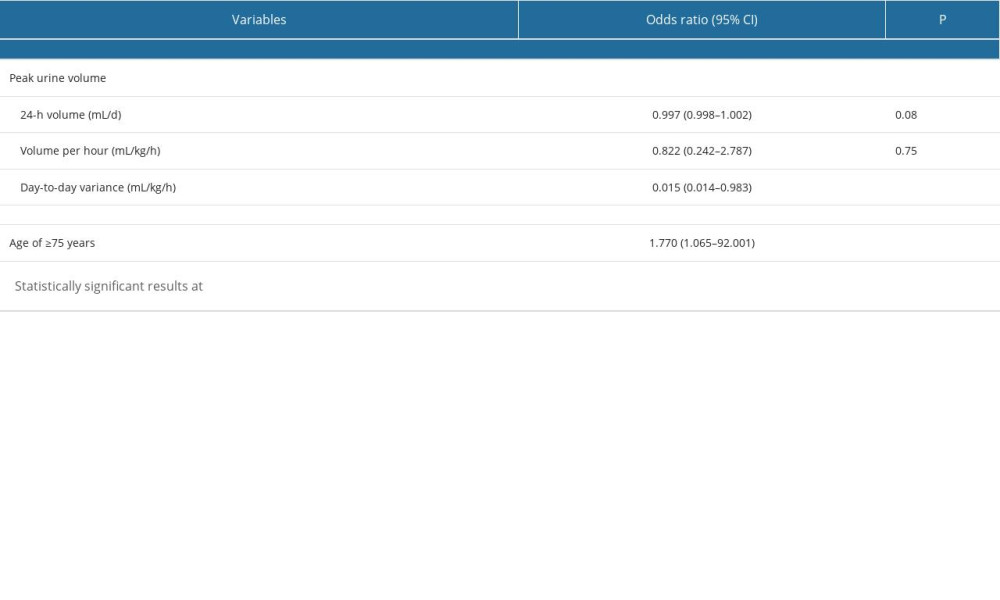

It is notable that approximately half (n=4, 44%) of patients who discontinued the drug treatment were older adults aged ≥75 years, with a ratio significantly greater than that of patients who completed therapy (9%; P=0.03). Compared with those who completed therapy, patients who discontinued therapy had significantly lower urine output (Table 2). Furthermore, logistic regression analysis in the total cohort demonstrated that patients with reduced day-to-day urine volume variation had more discontinuations within 48 hours thereafter. Older age (≥75 years) was an additional risk for the drug cessation.

ROC ANALYSIS:

In our 40 consecutive SAH cases, reduced day-to-day urine volume variation was significantly correlated with clazosentan discontinuation; therefore, the potential diagnostic utility of this parameter was evaluated in the ROC analysis. Urine volume variation of <−0.7 mL/kg/h was identified as the cut-off value for predicting the risk of drug intolerance, with a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 75% (Figure 2). The area under the curve (±standard error of the mean) on the ROC curve analysis was 0.76±0.10 (95% confidence interval: 0.56–0.96; P=0.035).

Discussion

The principle finding of this study was that approximately 20% of patients discontinued clazosentan anti-vasospasm therapy due to intolerable respiratory symptoms attributable to hypoxemia and pleural effusion at about 1 week after onset of treatment. The risk factors related involved decline of urine volume and elderly age (≥75 years), in which reduced day-to-day urine volume variation may predict subsequent drug discontinuation.

Clazosentan is a selective endothelin (ET)A receptor antagonist for intravenous use with a 1000 times higher binding affinity for ETA receptor than that for ETB receptor [17]. It is likely that the underlying mechanism of decreased day-to-day urine volume variation is fluid retention, presumably associated with ETA selective receptor antagonism. Unfortunately, there is no supportive pharmacological evidence regarding the adverse reaction of clazosentan to cause fluid retention in clinical trials in a human SAH population. However, other clinical data suggest that ETA selective antagonists, such as ambrisentan and sitaxentan [18,19], pose a greater risk of fluid overload in pulmonary arterial hypertension than dual antagonists [20]. In a rodent pharmacological study, ETB receptor overstimulation triggered by antagonizing ETA receptors was the key mechanism of fluid retention and vascular leakage [21]. These findings may help explain the high fluid retention and edema rates seen with clazosentan, particularly in conditions associated with elevated arginine vasopressin levels, such as congestive heart failure, older age, or renal dysfunction, which are frequently observed in patients with SAH, leading to reduced water excretion and increased vascular leakage.

What is the predictor of clazosentan therapy discontinuation? Among our older patients, urine output, including daily urine volume and day-to-day variance, and weight gain were significantly different between patients who completed and those who discontinued clazosentan therapy. Furthermore, logistic regression analysis in the total cohort demonstrated that day-to-day urine output variance could be the most plausible predictor, with a cut-off value of -0.7 mL/kg/h demonstrating a high sensitivity and specificity (Figure 1). Thus, acutely reduced urine output could be an initial warning sign of fluid redistribution and related hypoxemia.

According to available data, clazosentan is well tolerated by patients with SAH up to the expected therapeutic dose of 15 mg/h [5]. However, extracranial complications have also been reported, such as pulmonary disorders, anemia, and hypotension, but no practical solutions have been recommended beyond therapy interruption. Our results suggest that all potential risks must be managed by balancing potentially conflicting goals following SAH. Although clazosentan-related volumetric changes seem to be transient and reversible, therapeutic strategies should not be affected by other systemic causes hindering adequate volume retention and/or oxygenation, such as congestive heart failure and pneumonia. Recent studies have reported the importance of goal-directed therapy guided by extended hemodynamic monitoring in patients with post-SAH extracranial complications (eg, takotsubo cardiomyopathy and neurogenic pulmonary edema) [15,22–25]. In such situations, the benefit of cardiac and volumetric parameters for distinguishing between hypovolemia and fluid retention, and for guiding appropriate urine volume status, would be expected.

This study has some limitations. The study design was retrospective with a small sample size (n=40) from a single center; therefore, the therapeutic decision-making associated with clazosentan discontinuation should be examined in a larger population. Because of the single-arm design, no comparison with institutional standard protocol or placebo groups was demonstrated, which may be different from a previous study [14]. Nevertheless, given the higher rate of therapy discontinuation among older patients, our findings suggest that older patients are more vulnerable than younger adults to clazosentan, irrespective of its beneficial vasodilatory effects on cerebral vessels supported by recent clinical trials.

Conclusions

Our data obtained from 40 consecutive SAH patients suggest that intolerable respiratory events attributable to hypoxemia may be a warning sign of discontinuation of clazosentan therapy. We found that both reduced day-to-day urine volume variation and older age are independent risk factors for drug discontinuation.

Figures

Figure 1. An illustrative case of 81-year-old woman with SAH caused by ruptured aneurysm in right middle cerebral artery. (A) Non-contrast CT images on admission (upper panel) and postoperative day 1 (lower panel). (B) Volume-rendering enhanced CT angiography images on admission shows a large aneurysm in the right middle cerebral artery (yellow arrow) compatible with the clot distribution. (C) Serial changes of chest X-ray images before and after clazosentan therapy. CT – computed tomography; SAH – subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Figure 1. An illustrative case of 81-year-old woman with SAH caused by ruptured aneurysm in right middle cerebral artery. (A) Non-contrast CT images on admission (upper panel) and postoperative day 1 (lower panel). (B) Volume-rendering enhanced CT angiography images on admission shows a large aneurysm in the right middle cerebral artery (yellow arrow) compatible with the clot distribution. (C) Serial changes of chest X-ray images before and after clazosentan therapy. CT – computed tomography; SAH – subarachnoid hemorrhage.  Figure 2. ROC analysis of day-to-day urine volume variations in 40 postoperative SAH patients to predict the ability of clazosentan discontinuation (obtained from Prism version 9.5.1, GraphPad Software, USA). ROC – Receiver operating characteristic curve; SAH – subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Figure 2. ROC analysis of day-to-day urine volume variations in 40 postoperative SAH patients to predict the ability of clazosentan discontinuation (obtained from Prism version 9.5.1, GraphPad Software, USA). ROC – Receiver operating characteristic curve; SAH – subarachnoid hemorrhage. Tables

Table 1. Univariate analysis of general clinical data for clazosentan therapy between completed and discontinued groups among 40 postoperative SAH patients. Table 2. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of predictors of discontinuation of the clazosentan therapy in 40 postoperative SAH patients.

Table 2. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of predictors of discontinuation of the clazosentan therapy in 40 postoperative SAH patients.

References

1. Ziu E, Khan Suheb MZ, Mesfin FB, Subarachnoid hemorrhage: Statpearls Treasure June 1, 2023, Island (FL) Available from:https://www.statpearls.com/point-of-care/29607

2. Vergouwen MDI, Rinkel GJE, Emergency medical management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Neurocrit Care, 2023; 39; 51-58

3. Vespa PM, Bleck TP, Neurogenic pulmonary edema and other mechanisms of impaired oxygenation after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Neurocrit Care, 2004; 1; 157-70

4. Caylor MM, Macdonald RL, Pharmacological prevention of delayed cerebral ischemia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Neurocrit Care, 2023 [Online ahead of print]

5. Bruder N, Higashida R, Santin-Janin H, The react study: Design of a randomized phase 3 trial to assess the efficacy and safety of clazosentan for preventing deterioration due to delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: BMC Neurol, 2022; 22; 492

6. Muraoka S, Asai T, Fukui T, Real-world data of clazosentan in combination therapy for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A multicenter retrospective cohort study: Neurosurg Rev, 2023; 46; 195

7. Schupper AJ, Eagles ME, Neifert SN, Lessons from the CONSCIOUS-1 study: J Clin Med, 2020; 9; 2970

8. Macdonald RL, Kassell NF, Mayer S, Clazosentan to overcome neurological ischemia and infarction occurring after subarachnoid hemorrhage (CONSCIOUS-1): Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 dose-finding trial: Stroke, 2008; 39; 3015-21

9. Endo H, Hagihara Y, Kimura N, Effects of clazosentan on cerebral vasospasm-related morbidity and all-cause mortality after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Two randomized phase 3 trials in Japanese patients: J Neurosurg, 2022; 137; 1707-17

10. Lee A, Clazosentan: First approval: Drugs, 2022; 82; 697-702

11. Juif PE, Dingemanse J, Ufer M, Clinical pharmacology of clazosentan, a selective endothelin a receptor antagonist for the prevention and treatment of asah-related cerebral vasospasm: Front Pharmacol, 2020; 11; 628956

12. Ido K, Kurogi R, Kurogi A, Effect of treatment modality and cerebral vasospasm agent on patient outcomes after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in the elderly aged 75 years and older: PLoS One, 2020; 15; e0230953

13. Lanzino G, Kassell NF, Germanson TP, Age and outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Why do older patients fare worse?: J Neurosurg, 1996; 85; 410-18

14. Maeda T, Okawara M, Osakabe M, Initial real-world experience of clazosentan for subarachnoid hemorrhage in japan: World Neurosurg X, 2024; 21; 100253

15. Mutoh T, Kazumata K, Terasaka S, Early intensive versus minimally invasive approach to postoperative hemodynamic management after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Stroke, 2014; 45; 1280-84

16. Kuwano A, Ishiguro T, Nomura S, Predictive factors for improvement of symptomatic cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage by selective intra-arterial administration of fasudil hydrochloride: Interv Neuroradiol, 2023 [Online ahead of print]

17. Juif PE, Dingemanse J, Ufer M, Clinical pharmacology of clazosentan, a selective endothelin a receptor antagonist for the prevention and treatment of asah-related cerebral vasospasm: Front Pharmacol, 2020; 11; 628956

18. Galiè N, Barberà JA, Frost AE, Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension: N Engl J Med, 2015; 373; 834-44

19. Barst RJ, Langleben D, Frost A, Sitaxsentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2004; 169; 441-47

20. Rubin LJ, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: N Engl J Med, 2002; 346; 896-903

21. Vercauteren M, Trensz F, Pasquali A, Endothelin ETA receptor blockade, by activating ETB receptors, increases vascular permeability and induces exaggerated fluid retention: J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2017; 361; 322-33

22. Mutoh T, Kazumata K, Ajiki M, Goal-directed fluid management by bedside transpulmonary hemodynamic monitoring after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Stroke, 2007; 38; 3218-24

23. Mutoh T, Kazumata K, Terasaka S, Impact of transpulmonary thermodilution-based cardiac contractility and extravascular lung water measurements on clinical outcome of patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy after subarachnoid hemorrhage: A retrospective observational study: Crit Care, 2014; 18; 482

24. Mutoh T, Kazumata K, Kobayashi S, Serial measurement of extravascular lung water and blood volume during the course of neurogenic pulmonary edema after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Initial experience with 3 cases: J Neurosurg Anesthesiol, 2012; 24; 203-8

25. Mutoh T, Kazumata K, Ueyama-Mutoh T, Transpulmonary thermodilution-based management of neurogenic pulmonary edema after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Am J Med Sci, 2015; 350; 415-19

Figures

Figure 1. An illustrative case of 81-year-old woman with SAH caused by ruptured aneurysm in right middle cerebral artery. (A) Non-contrast CT images on admission (upper panel) and postoperative day 1 (lower panel). (B) Volume-rendering enhanced CT angiography images on admission shows a large aneurysm in the right middle cerebral artery (yellow arrow) compatible with the clot distribution. (C) Serial changes of chest X-ray images before and after clazosentan therapy. CT – computed tomography; SAH – subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Figure 1. An illustrative case of 81-year-old woman with SAH caused by ruptured aneurysm in right middle cerebral artery. (A) Non-contrast CT images on admission (upper panel) and postoperative day 1 (lower panel). (B) Volume-rendering enhanced CT angiography images on admission shows a large aneurysm in the right middle cerebral artery (yellow arrow) compatible with the clot distribution. (C) Serial changes of chest X-ray images before and after clazosentan therapy. CT – computed tomography; SAH – subarachnoid hemorrhage. Figure 2. ROC analysis of day-to-day urine volume variations in 40 postoperative SAH patients to predict the ability of clazosentan discontinuation (obtained from Prism version 9.5.1, GraphPad Software, USA). ROC – Receiver operating characteristic curve; SAH – subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Figure 2. ROC analysis of day-to-day urine volume variations in 40 postoperative SAH patients to predict the ability of clazosentan discontinuation (obtained from Prism version 9.5.1, GraphPad Software, USA). ROC – Receiver operating characteristic curve; SAH – subarachnoid hemorrhage. Tables

Table 1. Univariate analysis of general clinical data for clazosentan therapy between completed and discontinued groups among 40 postoperative SAH patients.

Table 1. Univariate analysis of general clinical data for clazosentan therapy between completed and discontinued groups among 40 postoperative SAH patients. Table 2. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of predictors of discontinuation of the clazosentan therapy in 40 postoperative SAH patients.

Table 2. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of predictors of discontinuation of the clazosentan therapy in 40 postoperative SAH patients. Table 1. Univariate analysis of general clinical data for clazosentan therapy between completed and discontinued groups among 40 postoperative SAH patients.

Table 1. Univariate analysis of general clinical data for clazosentan therapy between completed and discontinued groups among 40 postoperative SAH patients. Table 2. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of predictors of discontinuation of the clazosentan therapy in 40 postoperative SAH patients.

Table 2. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of predictors of discontinuation of the clazosentan therapy in 40 postoperative SAH patients. In Press

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparing Neuromuscular Blockade Measurement Between Upper Arm (TOF Cuff®) and Eyelid (TOF Scan®) Using Miv...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943630

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Enhancement of Frozen-Thawed Human Sperm Quality with Zinc as a Cryoprotective AdditiveMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942946

12 Mar 2024 : Database Analysis

Risk Factors of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Population-Based Study: Results from SHIP-TREND-1 (St...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943140

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952