02 October 2023: Clinical Research

Emerging Human Fascioliasis: A Retrospective Study of Epidemiological Findings in Dali, Yunnan Province, China (2012–2021)

Lihua Huang1ABCDE, Fuxing Li2ABCDE, Huiyong Su3BD, Jiao Luo1BCD, Wei Gu1AFG*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.940581

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940581

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Human fascioliasis is an emerging zoonotic disease caused by the trematodes, or flatworms, Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica, also known as liver flukes. This retrospective study aimed to report the epidemiological findings in 95 cases of human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China, diagnosed between 2012 and 2021.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The epidemiologic and clinical data of 95 patients diagnosed with human fascioliasis in Dali area from January 2012 to December 2021 were collected and retrospectively analyzed. The diagnosis of fascioliasis was based on the Chinese National Standard of Diagnosis of Fascioliasis (WS/T566-2017).

RESULTS: The mean age of patients was 38.54±15.68 years, and there were more female patients than male (61.05% vs 38.95%). The high-incidence seasons were identified as summer and autumn. The patients with human fascioliasis lived in pastoral areas or were infected F. gigantica by consuming contaminated vegetables or water containing metacercaria. Meanwhile, human fascioliasis was diagnosed by positive serologic tests (1: 640), and Fasciola eggs (144-180×73-96 μm) were detected in stool samples of 6 patients. The most common clinical features were abdominal pain (70.53%), accompanied by elevated eosinophils in 89.5% of these patients. Antiparasitic treatment with triclabendazole at 10 mg/kg/day for 2 days led to symptom relief in all patients.

CONCLUSIONS: The findings from this observational epidemiological study have highlighted the importance of recognizing, diagnosing, and managing fascioliasis, which is an emerging zoonosis associated with increased human proximity to plant-eating domestic and farmed animals.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, fascioliasis, triclabendazole, Prognosis, Adult, Animals, Humans, Middle Aged, young adult, China, Fasciola, Fasciola hepatica, Retrospective Studies, Zoonoses, Male, Female

Background

Fascioliasis is a zoonotic parasitic disease [1] caused mainly by the trematodes, or flatworms,

Current epidemiological data indicate that 180 million people worldwide are at risk of fascioliasis infection [5]; meanwhile, a meta-analysis showed a global prevalence of 4.5% for human fascioliasis [6]. Since the initial report of human fascioliasis in Fujian Province in 1921 [7], China experienced its first significant outbreak of 29 cases in Yunnan Province in 2012 [3]. Subsequently, the cumulative number of reported cases of human fascioliasis in China reached 306 as of 2019 [7].

Presently, the diagnosis of fascioliasis entails using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to identify antibodies against

Triclabendazole is the drug of choice for treating fascioliasis. However, the exact mechanism of its action has not been fully elucidated. Results derived from in vitro studies and animal models suggest that triclabendazole and its active metabolites (sulfoxides and sulfones) can be absorbed by the cortex of immature and mature

To achieve effective management of fascioliasis, it is imperative to enhance health education, promote health awareness among individuals, and foster hygienic eating habits. Additionally, it is crucial to strengthen the management of animal husbandry by implementing regular preventive deworming of livestock using triclabendazole, taking into consideration the epidemiological characteristics of endemic areas. Lastly, enhancing the professional competence of healthcare personnel and minimizing misdiagnosis are essential steps toward realizing effective management of fascioliasis [7].

In recent years, a growing number of clinical studies on human fascioliasis have been reported [4,11,12], contributing to clinicians’ understanding of the disease. In addition, a previous study reported the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of human fascioliasis in Dali area [3]; however, people infected with fascioliasis are often subject to missed or misdiagnosis, resulting in a prolonged course and potentially life-threatening consequences. Therefore, this retrospective study aimed to report the epidemiological findings in 95 cases of human fascioliasis in Dali, China, diagnosed between 2012 and 2021, with the aim of providing diagnostic and treatment recommendations for human fascioliasis cases in China.

Material and Methods

ETHICS STATEMENT:

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dali University (No. 20211020001), and informed consent was obtained from all participants or their family members.

STUDY POPULATION:

The study analyzed 95 cases of human fascioliasis treated between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2021, at the First Affiliated Hospital of Dali University and People’s Hospital of Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture. The diagnosis of fascioliasis was based on the National Standard of Diagnosis of Fascioliasis (WS/T566-2017) [9]. The diagnostic criteria for human fascioliasis include the following: (1) a documented history of residing, working, or traveling in an area where Fasciola is prevalent, along with a history of consuming aquatic plants or ingesting raw water; (2) the manifestation of symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, malaise, anorexia, vomiting, abdominal distension, and diarrhea, as well as the identification of an enlarged liver and tenderness in the hepatic region; (3) an elevation in the percentage and/or absolute count of eosinophils in the peripheral blood; and (4) the diagnosis of fascioliasis involves the utilization of various testing techniques, such as ELISA, to detect antibodies against Fasciola, the sedimentation technique to detect Fasciola eggs in fecal matter or duodenal drainage, or pathological sectioning to identify adult Fasciola.

DATA COLLECTION:

All patients’ data were collected from the hospital information system. The collected general information included demographics such as age, sex, and smoking and drinking history. Clinical manifestations included recorded vital signs, first symptoms, time from onset to admission, and length of hospital stay.

AUXILIARY EXAMINATION:

Routine blood tests assessed parameters such as white blood cells (WBC), percentage of neutrophils, percentage and absolute value of eosinophils, red blood cells, hemoglobin, and platelets. Liver and kidney function tests assessed total bilirubin, direct and indirect bilirubin, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), globulin, albumin, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and uric acid levels. Tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen (CA)125, and CA199, were also analyzed.

For the fecal examination by sedimentation technique, 3 independent fecal samples per patient were analyzed using the sedimentation technique to detect the presence of Fasciola species egg [13].

For the abdominal imaging examination, color Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were performed to assess the abdominal region.

For pathology, a liver biopsy, liver resection pathology, lower limb biopsy, and chest wall biopsy were conducted to examine the affected tissues.

THERAPY AND PROGNOSIS:

All patients diagnosed with human fascioliasis received triclabendazole therapy (10 mg/kg/day for 2 days). The triclabendazole used in the study was provided by the National Institute of Parasitic Disease, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The triclabendazole formulation included colloidal silicon dioxide, iron oxide red, lactose monohydrate, maize starch, magnesium stearate, and methyl-hydroxyethylcellulose. Patients were followed up via telephone during the first, third, and sixth months after treatment. The study reported that all patients had a good prognosis, with no deaths recorded.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The variables were reported as mean±standard deviation for continuous variables and counts (proportions) for categorical variables. To assess the statistical significance of differences between groups, categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, while continuous variables were analyzed using the

Results

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF 95 PATIENTS WITH HUMAN FASCIOLIASIS IN DALI, YUNNAN PROVINCE, SOUTHWESTERN CHINA:

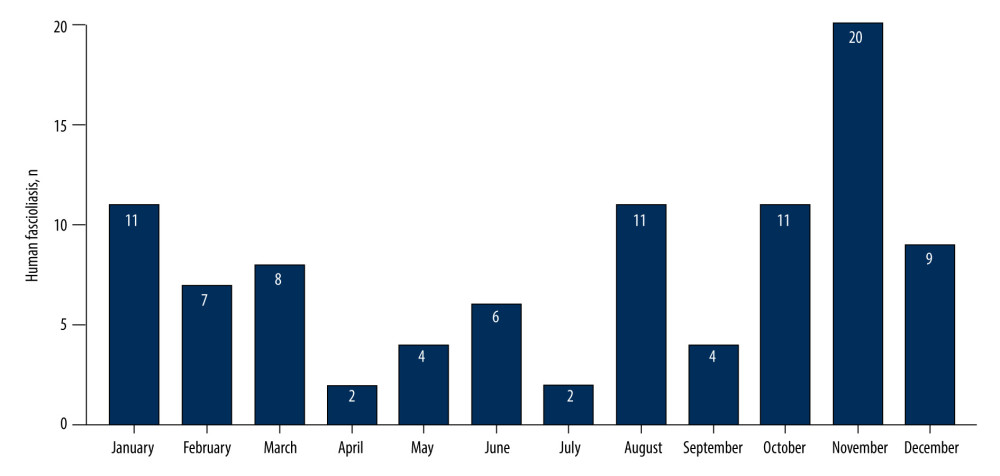

The cases of a total of 95 patients with human fascioliasis were analyzed, exhibiting female predominance (n=58, 61.05%) and a mean age of 38.54±15.68 years. Most of the patients were farmers from rural areas of Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture and resided close to water resources. It was observed that all patients had a history of consuming raw food prior to the onset of the disease. The high-incidence seasons were identified as summer and autumn, specifically from August to November. The distribution of reported cases of human fascioliasis across the year is illustrated in Figure 1. Demographics and clinical features are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

MAIN SYMPTOMS AND VITAL SIGNS:

The most common symptoms were abdominal pain (70.53%); it is noteworthy that the abdominal pain was predominantly localized to the right upper quadrant areas, as reported by 52.63% of the patients. Other frequently reported symptoms included fever (38.95%) and fatigue (12.63%). The average duration from the onset of symptoms to hospitalization was 61.46±52.21 days. Physical examination findings revealed that tenderness in the epigastrium or right epigastrium was the most common symptom (66.31%), followed by splenomegaly (26.25%), pleural effusion (9.47%), and hepatomegaly (4.21%). Only 2 patients presented with yellowish discoloration of the skin, sclera, and mucous membranes. Five of the patients underwent surgery due to abdominal pain and abdominal imaging (CT/MRI), suggestive of biliary obstruction caused by bile duct stones. Adult

LABORATORY TEST RESULTS:

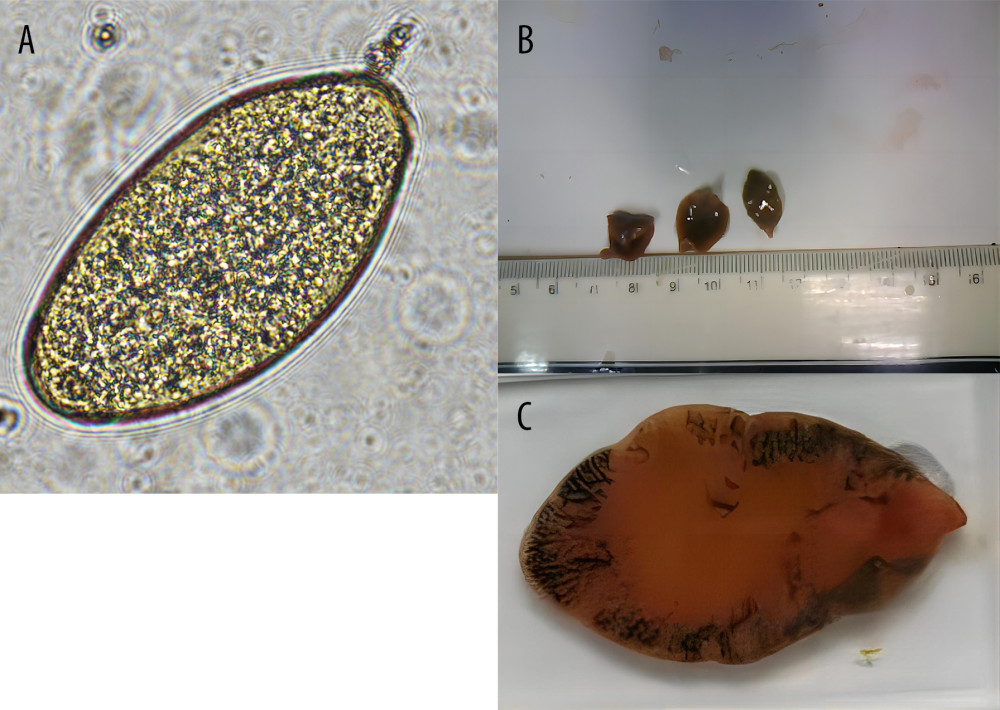

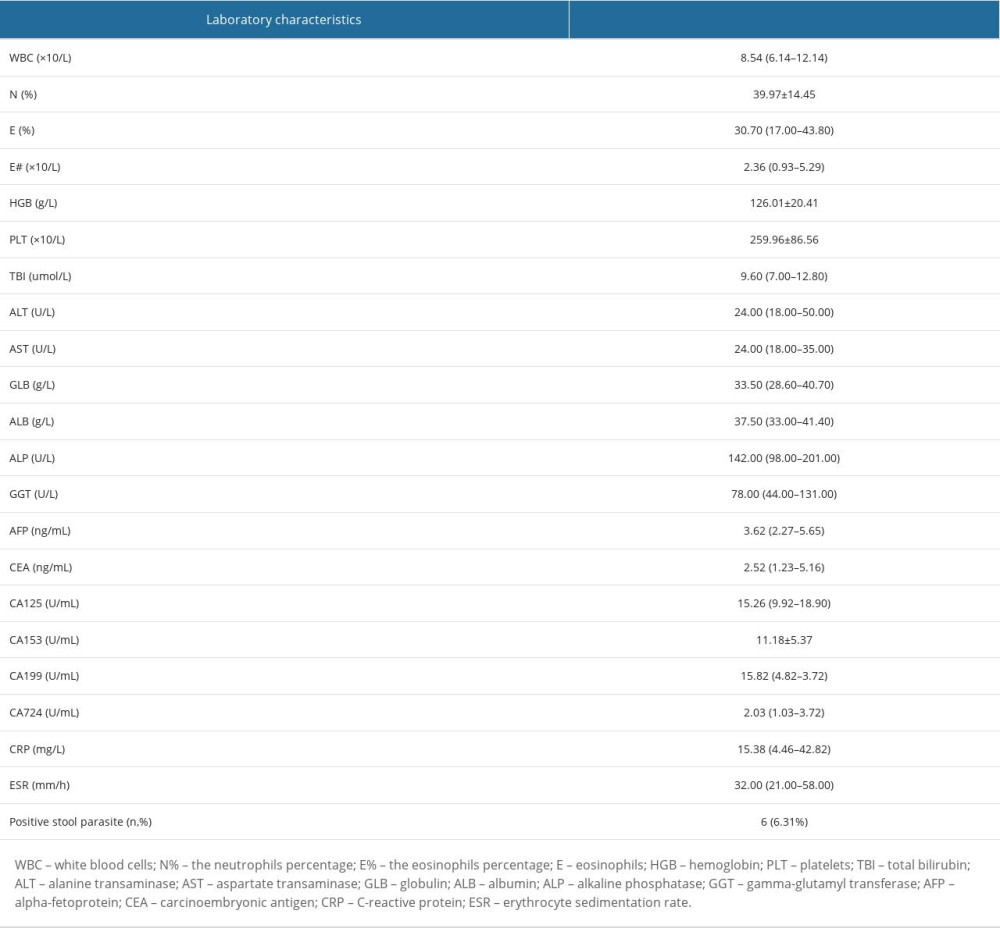

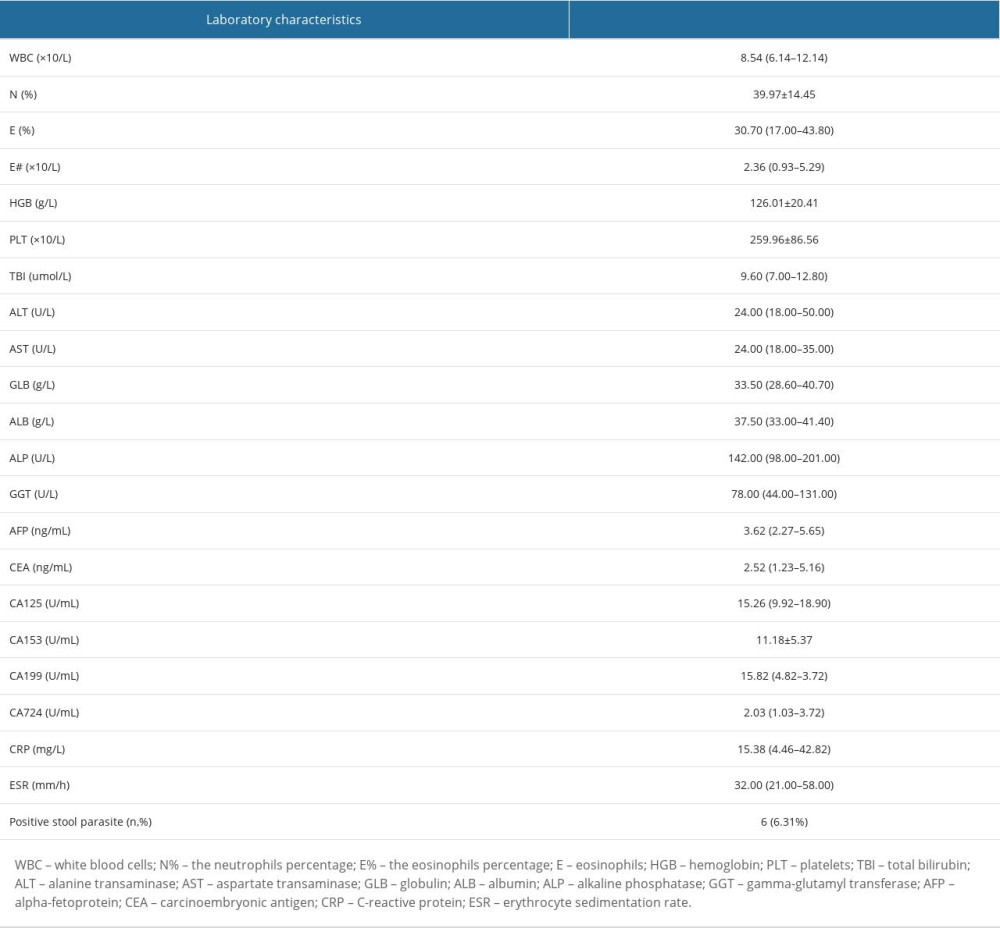

Of the total, 89.5% of patients exhibited increased eosinophils in peripheral blood (ie, percentage of eosinophils in peripheral blood of more than 5%), with a mean absolute value of eosinophils of 11.54×109/L. The incidences of anemia and leukocytosis were 34.74% and 36.84%, respectively, with 1 patient who experienced a leukemoid reaction due to a secondary bacterial infection. It is worth noting that platelets were within the normal range in all patients. In terms of liver function, 44 (46.32%) patients and 65 (68.42%) patients had elevated ALP and GGT, respectively. Also, 23 (24.21%) patients and 13 (13.68%) patients had increased ALT and AST, respectively. One patient had a total bilirubin level exceeding 5 mg/dL (reference range: 0.28–1.06 mg/dL) due to bile duct obstruction caused by adult Fasciola. Furthermore, only 1 patient exhibited an elevated serum creatinine level, at 330 μmol/L. For serodiagnosis, ELISA using soluble crude antigen of adult Fasciola was conducted, and all results were positive (1: 640) for Fasciola-specific antibodies. Fasciola eggs (144–180×73–96 μm, ×400) were detected in stool samples of 6 patients (Figure 2A), and adult Fasciola were extracted from the common bile duct of 2 patients (Figure 2B, 2C).

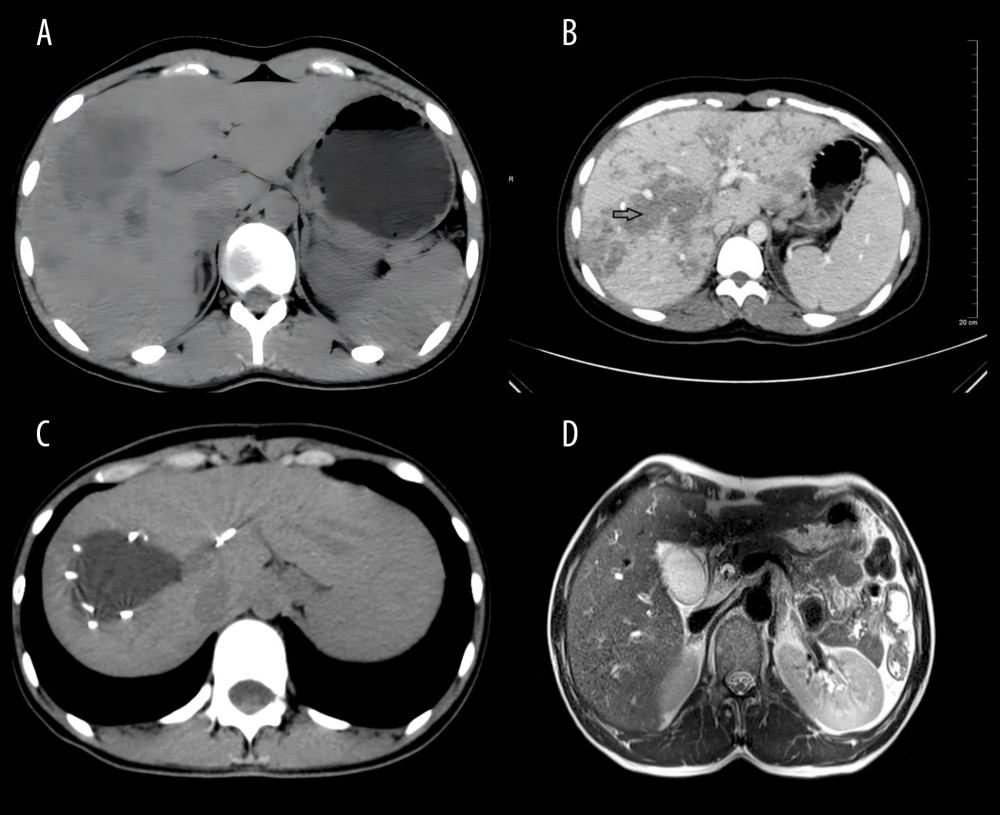

IMAGING RESULTS:

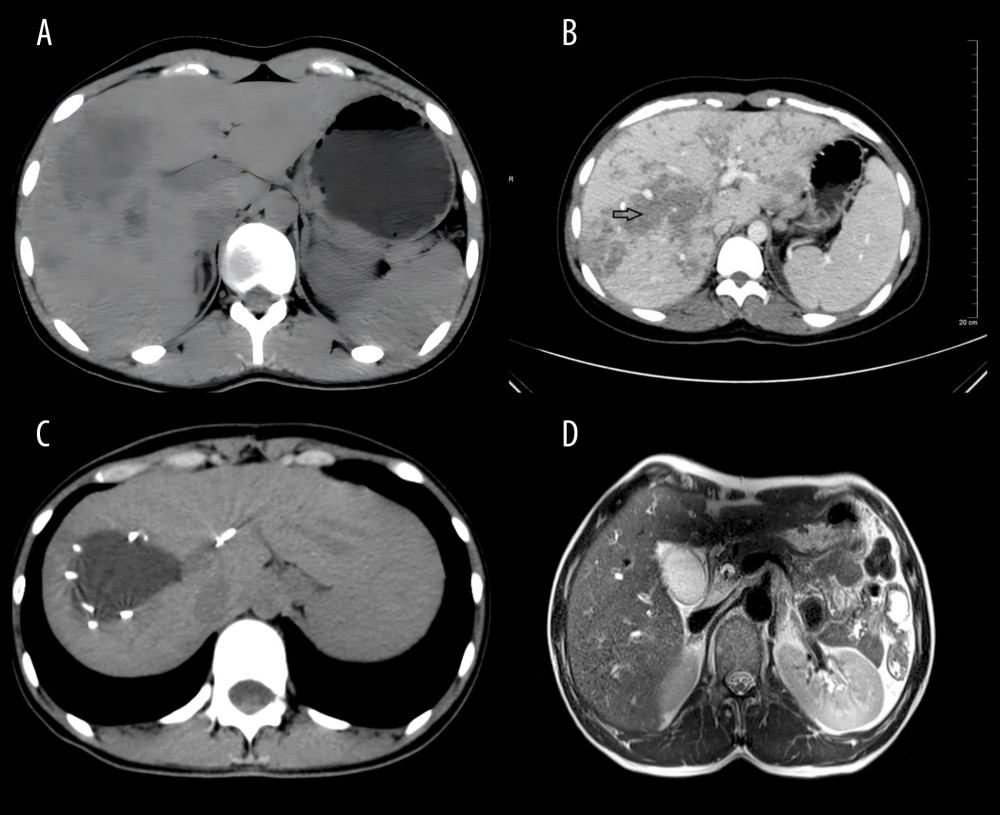

Abdominal ultrasound, CT, or MRI were conducted for all patients. Ultrasonographic findings were nonspecific and included multiple heterogeneous, slightly hyperechoic, or cystic masses in the liver. The CT scan in Figure 3A shows gathered or scattered low-density shadows. The contrast-enhanced CT in Figure 3B shows clustered or tunnel-like lesions under the liver capsule, without significant enhancement (indicated by arrows). Figure 3C shows large cystic lesions with smooth edges in the liver parenchyma, measuring 5–6 cm in diameter, with scattered punctate calcifications around them. MRI results in Figure 3D (T2 axial) reveal the presence of adult Fasciola in the dilated common bile duct. Extrahepatic findings included intraperitoneal lymphadenopathy (40.6%), ascites (18.1%), bile duct dilatation (14.9%), liver enlargement (8.5%), and abdominal wall abscess (2.1%).

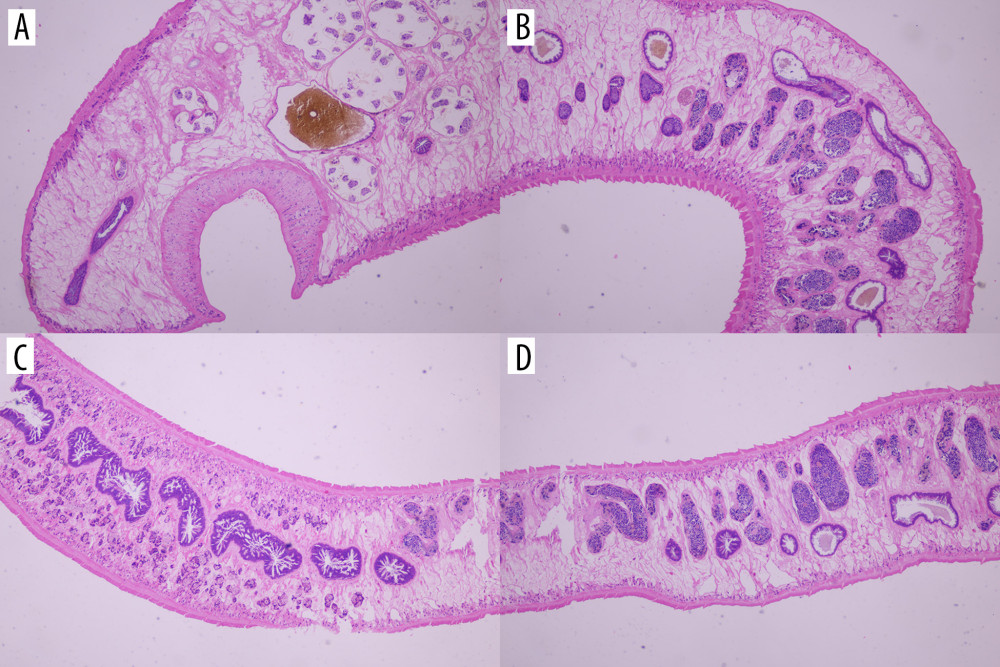

PATHOLOGICAL RESULTS:

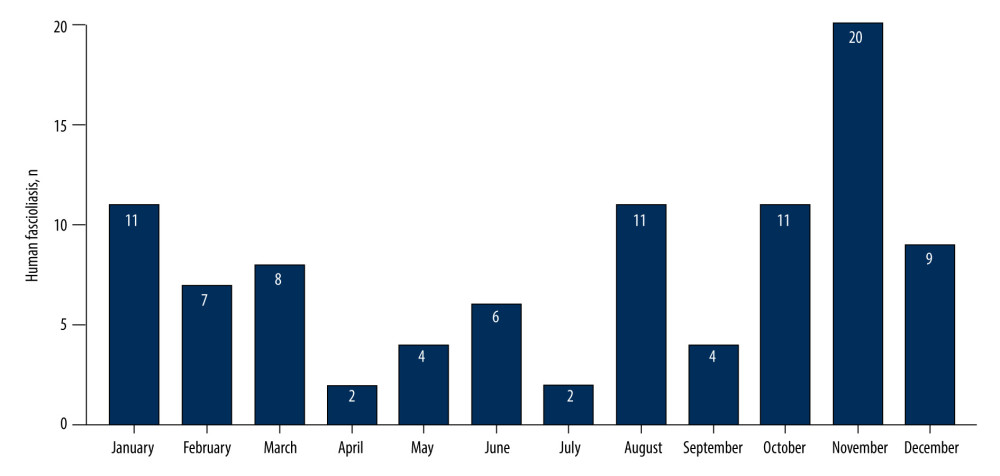

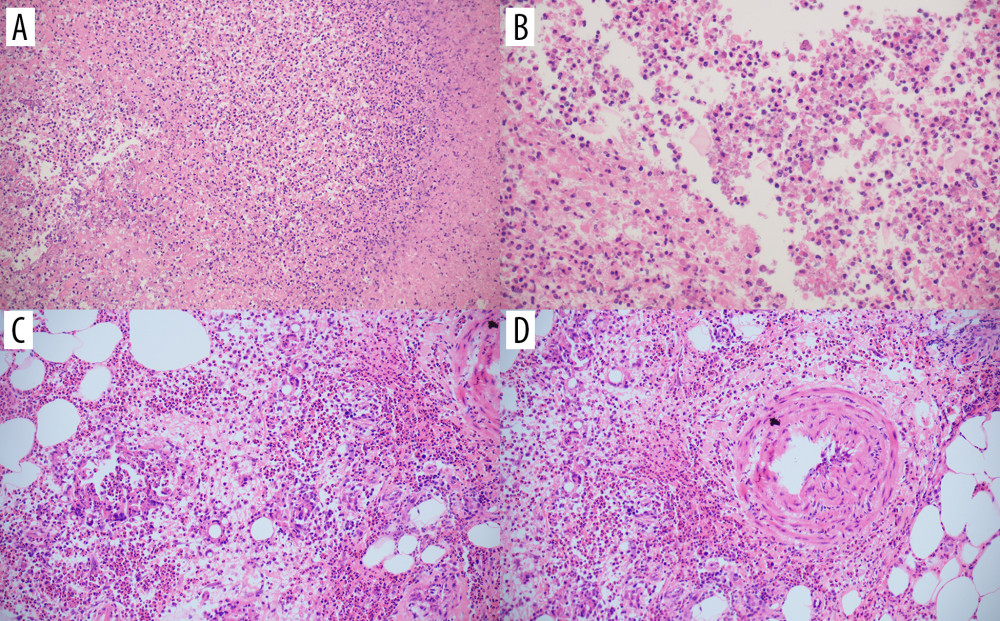

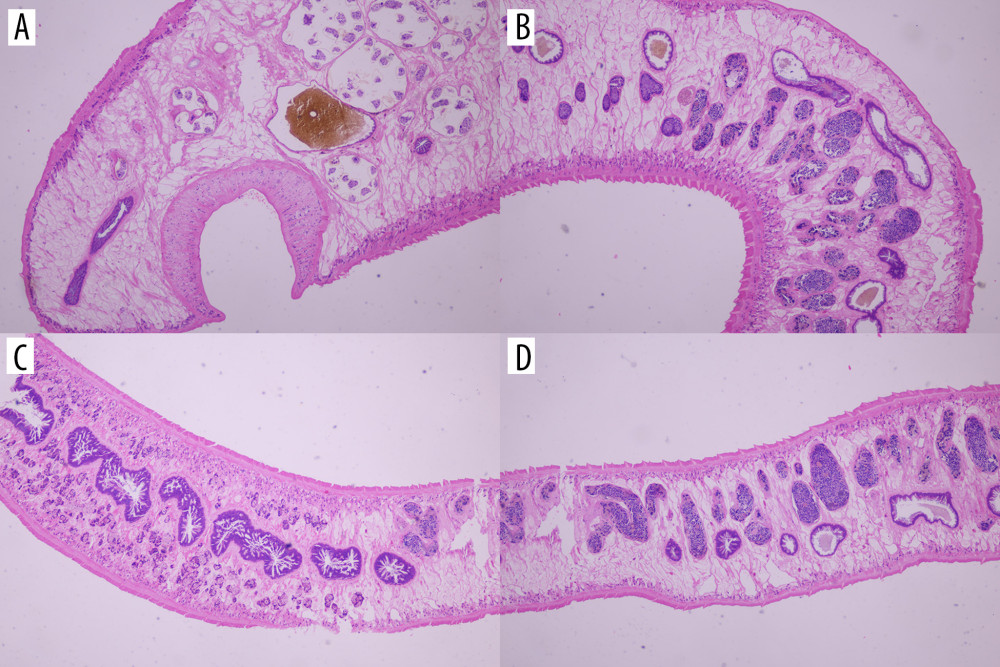

A liver biopsy was performed on 15 patients to establish a histopathological diagnosis of fascioliasis. Also, 3 patients underwent partial hepatectomy due to misdiagnosis of liver cancer. Eosinophilic infiltration and abscesses characterized by irregular tunnel formation were observed in the aforementioned patient (Figure 4A, 4B), and Charcot-Leyden crystals were found in 17 patients; however, no parasites were detected in the liver specimens. A skin biopsy was conducted on 1 patient with a rash on the lower limbs. The results indicated intimal proliferation and thickening of local small vascular (Figure 4C) and eosinophil infiltration in the interlobular septum of subcutaneous fat (Figure 4D), which were considered as eosinophilic panniculitis secondary to fascioliasis. In addition, 1 patient developed pruritus, with nodules on the chest wall, and the biopsy showed significant eosinophil infiltrating with Charcot-Leyden crystals. Four patients underwent bone marrow biopsy, which indicated eosinophil infiltration. As displayed in Figure 5A–5D, the worm taken from the patient was diagnosed as Fasciola, according to its gross morphology and pathology.

THERAPY AND PROGNOSIS:

In our study, triclabendazole was administered to 91 patients as the primary treatment for human fascioliasis. The oral daily dose of triclabendazole was 10 mg/kg, given in 3 doses for 2 days. Four patients initially received other medications, such as albendazole, mebendazole, or artemether, but later switched to triclabendazole due to the unsatisfactory effect of the previous treatment. Actually, the disappearance of clinical symptoms and images and the return to normal laboratory values in treated patients are strong evidence of the resolution of the infection. A total of 92 patients were successfully followed up for clinical symptoms, laboratory results, and imaging findings. The clinical symptoms of 90 patients almost disappeared 35 days after triclabendazole treatment. The eosinophil count and liver function parameters ALT, AST, ALP, and GGT returned to normal within 3 months. Imaging revealed that lesions completely disappeared in 60 patients (63.16%) after 6 months. No deaths were observed in our study.

Discussion

LIMITATIONS:

Although we made some important discoveries in this study, we need to point out some limitations. First, as a retrospective clinical study, it is important to acknowledge the potential presence of selection bias. Additionally, the limited sample size further emphasizes the necessity for a comprehensive prospective study involving multiple centers to validate our findings. Apart from the above, the adult Fasciola from patients included in Figure 2B and 2C do not show the typical form of F. gigantica, which suggests that they were probably immature young specimens, not appropriately fixed and mounted. Finally, owing to practical constraints, timely monitoring of dynamic changes in laboratory indicators was unfeasible, and the follow-up duration for patients with human fascioliasis was limited to 6 months, a relatively brief interval. Consequently, a longer follow-up period is warranted to enable a more comprehensive evaluation of the prognosis.

Conclusions

Human fascioliasis is a neglected parasitic disease caused by the parasites

Figures

Figure 1. Distribution of 95 patients with human fascioliasis by hospital admission month. GraphPad Prism 9.0, GraphPad Software, Inc.

Figure 1. Distribution of 95 patients with human fascioliasis by hospital admission month. GraphPad Prism 9.0, GraphPad Software, Inc. ![(A) Fasciola eggs (153×80 μm [× 400]) were detected in stool samples of patients with human fascioliasis; (B, C) Adult Fasciola were detected in bile ducts of patients with human fascioliasis (macroscopic view).](https://jours.isi-science.com/imageXml.php?i=medscimonit-29-e940581-g002.jpg&idArt=940581&w=1000) Figure 2. (A) Fasciola eggs (153×80 μm [× 400]) were detected in stool samples of patients with human fascioliasis; (B, C) Adult Fasciola were detected in bile ducts of patients with human fascioliasis (macroscopic view).

Figure 2. (A) Fasciola eggs (153×80 μm [× 400]) were detected in stool samples of patients with human fascioliasis; (B, C) Adult Fasciola were detected in bile ducts of patients with human fascioliasis (macroscopic view).  Figure 3. (A) Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showing multiple low-density shadows under the liver capsule. (B) Abdominal CT and enhanced CT showing clustered and/or tunnel-like lesions under the liver capsule, without significant enhancement (arrowhead). (C) Upper-abdominal CT and enhanced CT showing large cystic lesions in the liver parenchyma with smooth edges, and multiple punctate calcifications scattered around. (D) Adult Fasciola in the dilated common bile duct in T2 axial of magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 3. (A) Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showing multiple low-density shadows under the liver capsule. (B) Abdominal CT and enhanced CT showing clustered and/or tunnel-like lesions under the liver capsule, without significant enhancement (arrowhead). (C) Upper-abdominal CT and enhanced CT showing large cystic lesions in the liver parenchyma with smooth edges, and multiple punctate calcifications scattered around. (D) Adult Fasciola in the dilated common bile duct in T2 axial of magnetic resonance imaging. ![(A) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing massive eosinophil infiltration and abscesses (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain, ×100 magnification). (B) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing eosinophilic infiltration and abscesses characterized by irregular tunnel formation (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (C) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing intimal proliferation and thickening of small vascular (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (D) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing eosinophil infiltration in the interlobular septum of subcutaneous fat (H&E stain, ×200 magnification).](https://jours.isi-science.com/imageXml.php?i=medscimonit-29-e940581-g004.jpg&idArt=940581&w=1000) Figure 4. (A) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing massive eosinophil infiltration and abscesses (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain, ×100 magnification). (B) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing eosinophilic infiltration and abscesses characterized by irregular tunnel formation (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (C) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing intimal proliferation and thickening of small vascular (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (D) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing eosinophil infiltration in the interlobular septum of subcutaneous fat (H&E stain, ×200 magnification).

Figure 4. (A) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing massive eosinophil infiltration and abscesses (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain, ×100 magnification). (B) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing eosinophilic infiltration and abscesses characterized by irregular tunnel formation (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (C) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing intimal proliferation and thickening of small vascular (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (D) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing eosinophil infiltration in the interlobular septum of subcutaneous fat (H&E stain, ×200 magnification).  Figure 5. Pathology of adult Fasciola (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200 magnification). (A) is the head of the adult Fasciola; (B) is the body of the adult Fasciola; and (C, D) are tail of the adult Fasciola.

Figure 5. Pathology of adult Fasciola (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200 magnification). (A) is the head of the adult Fasciola; (B) is the body of the adult Fasciola; and (C, D) are tail of the adult Fasciola. References

1. Good R, Scherbak D, Fascioliasis. [Updated 2023 May 1]: StatPearls [Internet], 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537032/2

2. Rokni MB, The present status of human helminthic diseases in Iran: Ann Trop Med Parasitol, 2008; 102(4); 283-95

3. Chen JX, Chen MX, Ai L: PLoS One, 2013; 8(8); e71520

4. Mas-Coma S, Valero MA, Bargues MD, Human and animal fascioliasis: Origins and worldwide evolving scenario: Clin Microbiol Rev, 2022; 35(4); e0008819

5. Pan M, Bai SY, Ji TK: Acta Trop, 2022; 230; 106394

6. Rosas-Hostos Infantes LR, Paredes Yataco GA, Ortiz-Martínez Y, The global prevalence of human fascioliasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Ther Adv Infect Dis, 2023; 10; 20499361231185413

7. Ai L, Chen JX, Cai YC, Prevalence and risk factors of Fascioliasis in China: Acta Trop, 2019; 196; 180-88

8. Rehman T, Khan MN, Abbas RZ: J Helminthol, 2016; 90(4); 494-502

9. : National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China.WS/T 566-2017 Diagnosis of fascioliasis [S], 2017, Beijing, China Standards press Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/s9499/wsbz.shtml

10. Kelley JM, Elliott TP, Beddoe T: Trends Parasitol, 2016; 32(6); 458-69

11. González-Miguel J, Valero MA, Reguera-Gomez M, Numerous Fasciola plasminogen-binding proteins may underlie blood-brain barrier leakage and explain neurological disorder complexity and heterogeneity in the acute and chronic phases of human fascioliasis: Parasitology, 2019; 146(3); 284-98 [Erratum in: Parasitology. 2020;147(6):729]

12. Caravedo MA, Cabada MM, Human fascioliasis: Current epidemiological status and strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and control: Res Rep Trop Med, 2020; 11; 149-58

13. Perrodin S, Walti L, Gottstein B: Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr, 2019; 8(6); 597-603

14. Sunita K, Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD: Acta Parasitol, 2021; 66(4); 1396-405

15. Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA, Human fascioliasis infection sources, their diversity, incidence factors, analytical methods and prevention measures: Parasitology, 2018; 145(13); 1665-99 [Erratum in: Parasitology. 2020;147(5): 601]

16. Karahocagil MK, Akdeniz H, Sunnetcioglu M, A familial outbreak of fascioliasis in Eastern Anatolia: A report with review of literature: Acta Trop, 2011; 118(3); 177-83

17. Valero MA, Bargues MD, Khoubbane M: Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 2016; 110(1); 55-66

18. Tavil B, Ok-Bozkaya İ, Tezer H, Tunç B, Severe iron deficiency anemia and marked eosinophilia in adolescent girls with the diagnosis of human fascioliasis: Turk J Pediatr, 2014; 56(3); 307-9

19. Le TH, De NV, Agatsuma T: J Clin Microbiol, 2007; 45(2); 648-50

20. Moshfe A, Aria A, Erfani N, Clinical features, diagnosis and management of patients with suspicion of fascioliasis in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province, Southwestern Iran: Iran J Parasitol, 2020; 15(1); 84-90

21. Smith ML, Colwell B, Forté CA, Psychosocial correlates of smokeless tobacco use among Indiana adolescents: J Community Health, 2015; 40(2); 208-14

22. Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA, Diagnosis of human fascioliasis by stool and blood techniques: update for the present global scenario: Parasitology, 2014; 141(14); 1918-46

23. Leerapun A, Puasripun S, Kijdamrongthum P, Thongsawat S, Human fascioliasis presenting as liver abscess: Clinical characteristics and management: Hepatol Int, 2021; 15(3); 804-11

24. Kaya M, Beştaş R, Cetin S: World J Gastroenterol, 2011; 17(44); 4899-904

25. Gandhi P, Schmitt EK, Chen CW, Samantray S, Triclabendazole in the treatment of human fascioliasis: A review: Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 2019; 113(12); 797-804

26. Fang W, Chen F, Liu HKComparison between albendazole and triclabendazole against Fasciola gigantica in human: Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi, 2014; 26(1); 106-8 [in Chinese]

27. Gil LC, Díaz A, Rueda CResistant human fasciolasis: Report of four patients: Rev Med Chil, 2014; 142(10); 1330-33 [in Spanish]

Figures

Figure 1. Distribution of 95 patients with human fascioliasis by hospital admission month. GraphPad Prism 9.0, GraphPad Software, Inc.

Figure 1. Distribution of 95 patients with human fascioliasis by hospital admission month. GraphPad Prism 9.0, GraphPad Software, Inc. Figure 2. (A) Fasciola eggs (153×80 μm [× 400]) were detected in stool samples of patients with human fascioliasis; (B, C) Adult Fasciola were detected in bile ducts of patients with human fascioliasis (macroscopic view).

Figure 2. (A) Fasciola eggs (153×80 μm [× 400]) were detected in stool samples of patients with human fascioliasis; (B, C) Adult Fasciola were detected in bile ducts of patients with human fascioliasis (macroscopic view). Figure 3. (A) Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showing multiple low-density shadows under the liver capsule. (B) Abdominal CT and enhanced CT showing clustered and/or tunnel-like lesions under the liver capsule, without significant enhancement (arrowhead). (C) Upper-abdominal CT and enhanced CT showing large cystic lesions in the liver parenchyma with smooth edges, and multiple punctate calcifications scattered around. (D) Adult Fasciola in the dilated common bile duct in T2 axial of magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 3. (A) Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showing multiple low-density shadows under the liver capsule. (B) Abdominal CT and enhanced CT showing clustered and/or tunnel-like lesions under the liver capsule, without significant enhancement (arrowhead). (C) Upper-abdominal CT and enhanced CT showing large cystic lesions in the liver parenchyma with smooth edges, and multiple punctate calcifications scattered around. (D) Adult Fasciola in the dilated common bile duct in T2 axial of magnetic resonance imaging. Figure 4. (A) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing massive eosinophil infiltration and abscesses (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain, ×100 magnification). (B) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing eosinophilic infiltration and abscesses characterized by irregular tunnel formation (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (C) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing intimal proliferation and thickening of small vascular (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (D) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing eosinophil infiltration in the interlobular septum of subcutaneous fat (H&E stain, ×200 magnification).

Figure 4. (A) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing massive eosinophil infiltration and abscesses (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain, ×100 magnification). (B) Pathological results of liver biopsy results showing eosinophilic infiltration and abscesses characterized by irregular tunnel formation (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (C) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing intimal proliferation and thickening of small vascular (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). (D) Skin biopsy of lower limbs showing eosinophil infiltration in the interlobular septum of subcutaneous fat (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). Figure 5. Pathology of adult Fasciola (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200 magnification). (A) is the head of the adult Fasciola; (B) is the body of the adult Fasciola; and (C, D) are tail of the adult Fasciola.

Figure 5. Pathology of adult Fasciola (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200 magnification). (A) is the head of the adult Fasciola; (B) is the body of the adult Fasciola; and (C, D) are tail of the adult Fasciola. Tables

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of 95 patients with human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of 95 patients with human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China. Table 2. Laboratory characteristics of 95 patients with human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China.

Table 2. Laboratory characteristics of 95 patients with human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China. Table 1. Clinical characteristics of 95 patients with human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of 95 patients with human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China. Table 2. Laboratory characteristics of 95 patients with human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China.

Table 2. Laboratory characteristics of 95 patients with human fascioliasis in Dali, Yunnan Province, southwestern China. In Press

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952