12 December 2022: Clinical Research

Preoperative Biologics Exposure Predisposes Ulcerative Colitis Patients to a Distinct Delayed Postoperative Ileus Syndrome After Colectomy

Zhenyu Yuan1ABCEF, Liying Cui1ACD, Suting Liu1BCD, Wenhao Zhang1AEF, Qing Ji1ADE*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.938412

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e938412

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Postoperative ileus (POI) remains the most common complication after colectomy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Delayed POI (DPOI) can develop late (>14 days) after colectomy in clinical settings, with unknown etiology. The aim of this study was to address a novel entity of POI after colectomy for ulcerative colitis (UC).

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The data of 263 UC patients who underwent colectomy from Jan 1, 2013 to May 31, 2021 were collected. DPOI was defined as POI occurring on or after postoperative day (POD) 14 with apparent resolution from obligatory POI. Univariate and multivariate analysis were conducted to identify the risk factors for DPOI.

RESULTS: The rate of canonical prolonged POI and DPOI were 11.7% (31/263) and 9.9% (26/263), respectively. The pathophysiological process of DPOI demonstrated an ileus-dysbiosis-recovery triad. Two DPOI cases were diagnosed with UC-related severe enteritis and underwent re-laparotomy. Multivariate analysis showed preoperative biologics exposure was an independent risk factor for DPOI (OR 3.100 95% CI 1.261-7.619, P=0.018) and the number of biologics session/course moderately predicted the occurrence of DPOI (AUC=0.639, 95% CI=0.578-0.697, P=0.0129).

CONCLUSIONS: A distinct pattern of ileus was identified in a tertiary IBD center. Clarification of this syndrome complemented the spectrum of post-IPAA complications and offered experience to treat this condition.

Keywords: Colectomy, Dysbiosis, Ileus, Humans, Biological Products, Colitis, Ulcerative, Syndrome, Intestinal Obstruction, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic disease characterized by a relapsing and remitting course [1]. Despite the emergence of novel treatments, colectomy is required in approximately 10% of patients within 5 years of UC diagnosis in the biologics era [2,3]. However, postoperative recovery from this procedure is sometimes eventful due to short- and long-term complications and comorbidities, which is also the major obstacle for application of ERAS protocol in this population.

Postoperative ileus (POI) is generally understood as a disruption of the regularly orchestrated, propulsive activity of the gastrointestinal tract after surgery [4]. While physiological POI is considered as a normal, self-limited response to an operation, POI that persists over 4 days postoperatively is considered as prolonged POI (PPOI), which is associated with increased morbidity [5]. A previous study showed that ileus was the most common complication after colectomy, with the largest overall effect on length of postoperative hospitalization [6].

A meta-analysis found that up to 18% of UC patients had POI [7] and preoperative biologics exposure was associated with increased risk of POI [8,9]. However, the definitions of POI in these studies were ambiguous and most likely referred to PPOI. Our clinical observations indicated the existence of a novel entity in the POI spectrum, which is difficult to identify and may result in a misnomer. To the best of our knowledge, these patients had passage of ileostomy output and restoration of oral intake or nasal feeding, but developed a recurrent POI days after resolution of first POI or after discharge, typically 2 weeks postoperatively.

Here, we described a distinct pattern of gastrointestinal dysmotility that occurred after recovery from the normal POI, and termed it “delayed postoperative ileus (DPOI)”. This retrospective cohort study aimed to investigate the disease pattern and risk factors for DPOI.

Material and Methods

PATIENTS’ CHARACTERISTICS:

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinling hospital. Consecutive patients who underwent surgery for medically refractory UC, stenosis, toxic megacolon, perforation, or severe bleeding in Jinling Hospital from Jan 1, 2013 to May 31, 2021 were screened from the IBD database. Inclusion criteria were (1) subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy, and (2) proctocolectomy with or without pouch construction. Patients who had 1-stage IPAA, IPAA for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), previous segmental or subtotal colectomy, postoperative pathology that precluded UC diagnosis, or who underwent surgery without colectomy (eg, proctectomy and IPAA with loop ileostomy [stage II of 3-staged IPAA], reversal of ileostomy, pouch excision or reconstruction, or irrigation of abdominal cavity) were excluded.

Demographic data and characteristics of the disease and its treatment were collected. These variables included sex, age at surgery, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, disease extent (left-sided [E2] or pancolitis [E3]), disease activity, emergent surgery, operation method (open, laparoscopic), type of surgery, history of medication, previous abdominal surgery, indications of surgery and postoperative length of stay, intraoperative parameters including duration of surgery (in minutes), and estimated blood loss (in mL). Preoperative 5-ASA, immunomodulators, and steroids use was defined as receiving 5-ASA, azathioprine, or 6-mercaptopurine and corticosteroids within 4 weeks before surgery. Preoperative biologics usage was defined as receiving infliximab [10], vedolizumab [8] or ustekinumab [11] administered within 12 weeks and adalimumab within 6 weeks prior to surgery [12].

PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT:

An enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol was implemented throughout the perioperative period. Briefly, early enteral nutrition (EN) was started 24 h after colectomy and adjusted depending on the patient’s tolerance. After tolerating EN, a semi-fluid diet was added, followed by a semi-solid diet. Patients were instructed to wean off EN with gradual resumption of normal diet. The urinary catheter was removed on POD 1. Postoperative pain control was performed using patient-controlled analgesia comprising sufentanil for up to 48 h.

ASSESSMENT OF POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS:

Infectious complications included surgical site infections (SSIs) (wound infection, abdominal/pelvic abscess, and anastomotic leakage), urinary tract infection (UTI), blood stream infection, and pneumonia. Obligatory postoperative ileus (POI) was defined as the interval from surgery until both the following criteria were met: 1) Passage of flatus or stool, 2) tolerance of an oral diet or enteral feeding. Prolonged POI was defined if 2 or more of the following 5 criteria were met on or after day 4 postoperatively without prior resolution of obligatory POI: 1) Nausea or vomiting; 2) Inability to tolerate an oral diet or enteral feeding over the last 24 h; 3) Absence of flatus or stool over last 24 h; 4) Abdominal distension; 5) Radiologic confirmation [5]. All patients who developed POI had immediate cessation of oral diet or enteral feeding. A nasogastric tube (NGT) for decompression was placed if necessary.

Delayed postoperative ileus was defined as POI that recurred on or after POD 14 with apparent resolution of obligatory POI. The DPOI patients had passage of flatus or stool, tolerated oral intake or enteral feeding, and, in some cases, were discharged before developing recurrent ileus that met 2 or more of the 5 criteria above. Additionally, a mandatory CT scan was performed to exclude mechanical bowel obstruction. Patients that recovered after intravenous fluid therapy were classified as stoma-related dehydration and therefore not regarded as DPOI.

CRITERIA FOR DISCHARGE:

The patient’s laboratory tests and vital signs were reviewed daily. In the absence of complications, patients were discharged if they tolerated a regular diet or full dosage of EN, had no fever (<37.5°C), passed stool, weaned off intravenous fluids, and were fully ambulant with oral analgesics.

STATISTICS:

Data for demographic characteristics were expressed as mean±SD or median (range). Kolmogorov-Smirnov method was used to test the normality of the variables. Continuous variables were analyzed using the

Results

PATIENTS:

A total of 286 UC patients underwent colectomy or proctectomy during the 9-year period, and 23 were excluded due to inconsistent postoperative pathology or incomplete data.

Among the 263 patients included in analysis, 145 (55.1%) were males. The mean age at colectomy was 43.2±13.7 years. Median disease duration was 33 (range, 1–186) months. For preoperative medication, 98 (37.3%) patients had 5-ASA, 35 (13.3%) had immunomodulators, 183 (69.6%) had steroids, and 65 (24.7%) had biologics. Two hundred and nineteen (83.3%) patients had laparoscopic surgery and 196 (74.5%) had proctocolectomy with pouch construction. The median postoperative length of stay was 8 (range, 3–42) days. Details of patient characteristics and perioperative parameters are summarized in Table 1. Infectious complications occurred in 43 (16.3%) patients and are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

INCIDENCE OF PROLONGED AND DELAYED POSTOPERATIVE ILEUS:

Early postoperatively, the interval from surgery to resolution of POI was longer than 4 days in 42 patients and 11 were was diagnosed with mechanical bowel obstruction based on radiological findings. Therefore, 31 (11.7%) patients were diagnosed with PPOI. These cases were canonical PPOI characterized by prolonged paralysis of gut motility without previous resolution. All patients had recovered from PPOI with either prokinetics and/or glucocorticoids treatment.

Seven patients had a second episode of ileus after prior resolution of POI at a mean time of 15 (range, 14–19) days postoperatively. Readmission for ileus occurred at a median time of 18 (range, 14–34) days postoperatively in 19 patients. Therefore, 7 in-hospital and 19 post-discharge cases of “delayed postoperative ileus (DPOI)” were diagnosed after excluding intestinal obstruction by abdominal CT scan. Patients who developed DPOI in-hospital had a median postoperative length of stay of 19 (range, 11–42) days. The median length of stay for readmission DPOI patients was 9 (range, 7–13) days.

DESCRIPTION AND TREATMENT OF DELAYED POSTOPERATIVE ILEUS:

Unlike PPOI, all 26 cases of DPOI shared distinct pathophysiological process with 3 phases: 1) cessation or decrease of ileostomy output with or without abdominal distension; 2) high-output ileostomy (typically >1500 mL/d) with purulent contents after passage of intestinal contents, with subsequent fecal test and culture confirming the concomitant enteric infection; 3) gradual reduction of the volume and appearance of ileostomy output. Notably, none of the PPOI cases without DPOI demonstrated the ileus-dysbiosis-recovery triad.

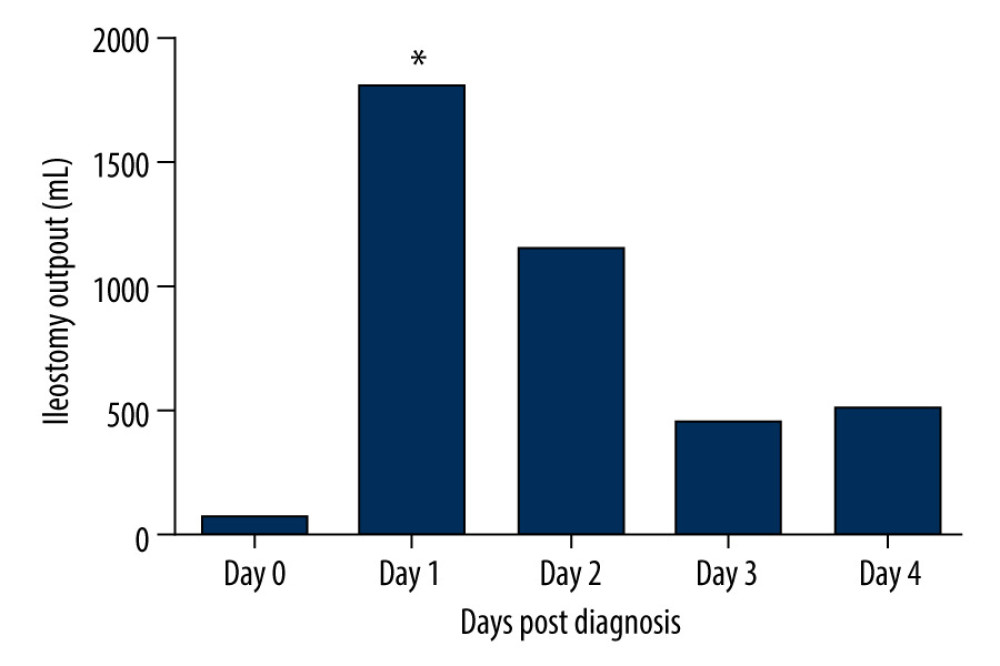

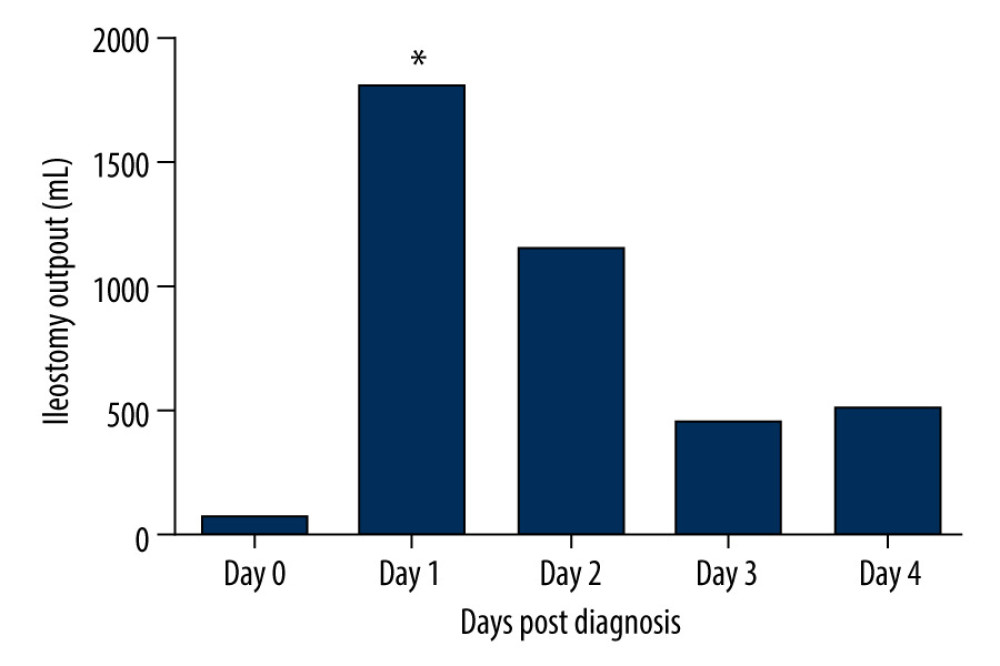

The median duration of the decreased stoma output was 2 (range, 1–5) days. Treatment for DPOI included nil per os, somatostatin/octreotide usage, and oral antibiotics (vancomycin or rifaximin) after ileostomy passage recovery. Somatostatin/octreotide was used until the patient had restored normal stoma output. Antibiotics were used for 7 consecutive days. Twenty-four recovered after conservative treatment and the dynamic changes of ileostomy output are shown in Figure 1. The last 24 h that constituted the diagnosis of DPOI were defined as day 0. The median volume of ileostomy output on day 0 to 4 were 60 (range, 0–100) mL, 1800 (range, 1200–3000) mL, 1150 (range, 400–2200) mL, 450 (range, 250–1000) mL, and 500 (range, 300–800) mL.

Two were reoperated on for hypovolemic shock due to massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Intraoperative explorations revealed sporadic superficial ulcers and obliteration of the vascular pattern of the mucosal layer. These findings concurred with the clinical features of UC-related severe enteritis (UCRSE) reported by Kohyama et al [13] and Shimoda et al [14]. No deaths were recorded in patients with DPOI. All DPOI patients were followed up until stoma closure and none developed another episode of ileus.

RISK FACTORS OF DELAYED POSTOPERATIVE ILEUS:

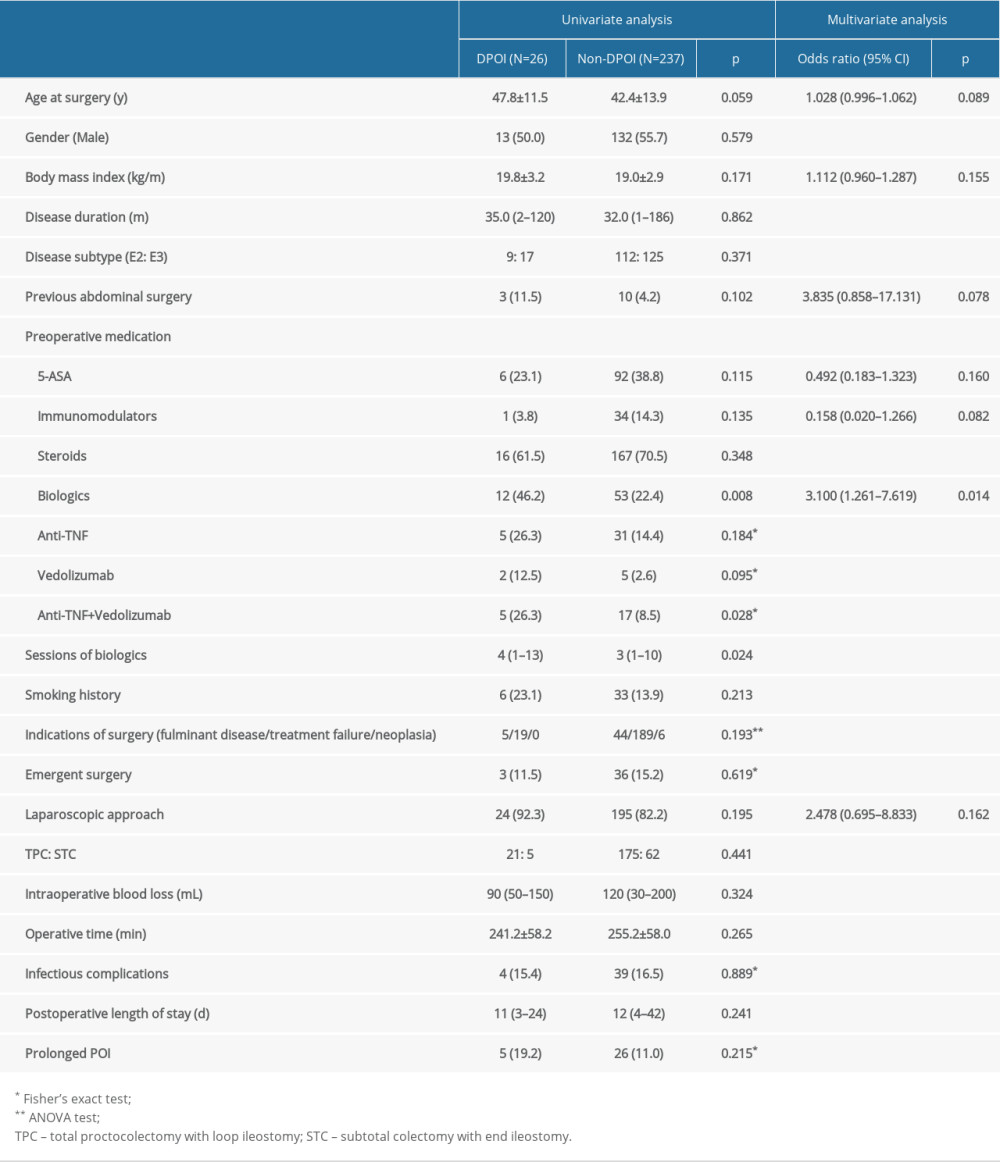

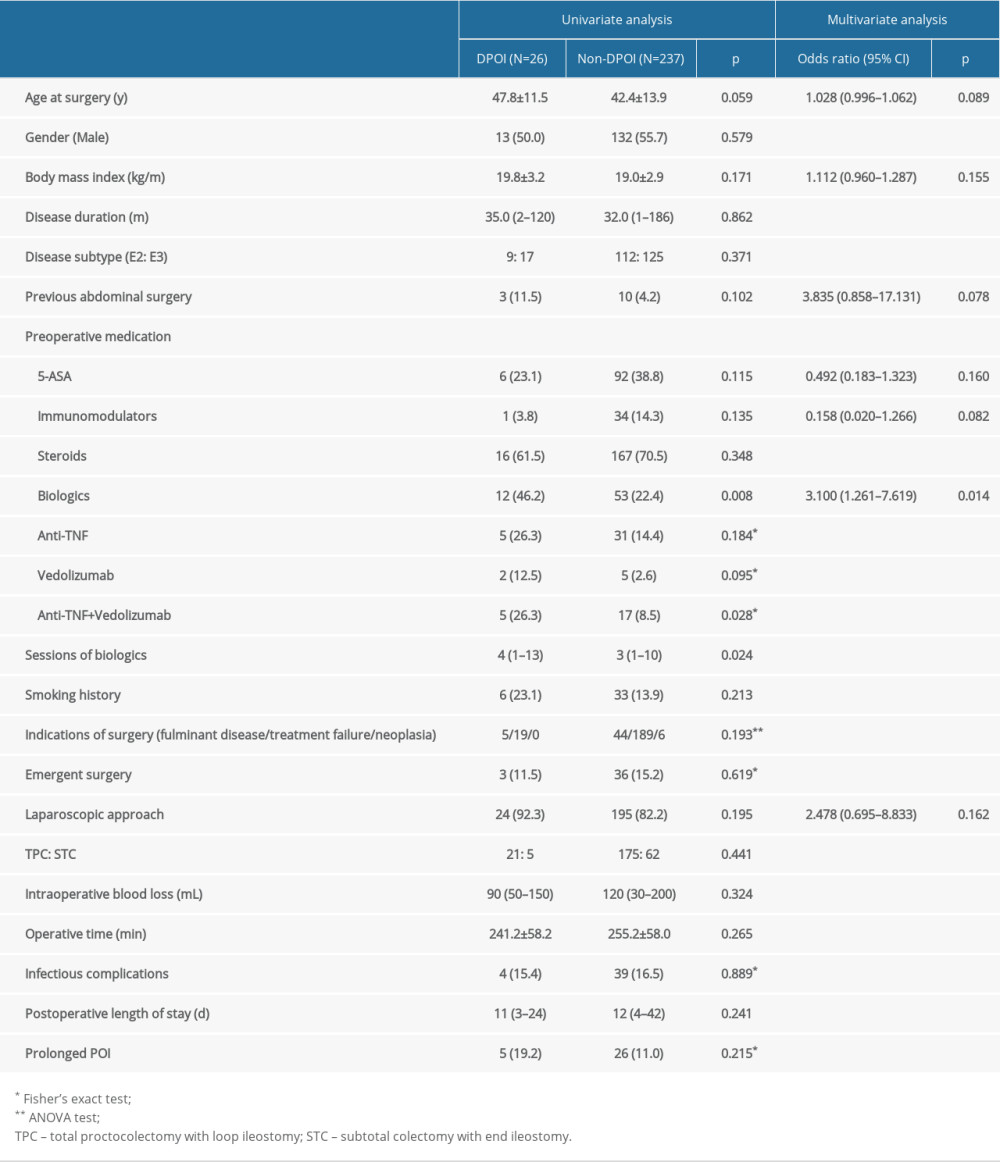

The results of univariate and multivariate are summarized in Table 2. Univariate analysis showed no significant differences between the DPOI and non-DPOI groups in sex, BMI, disease duration, disease subtype, preoperative inflammatory markers, preoperative medication except biologics, smoking history, emergent surgery, indications of surgery, intraoperative parameters, and postoperative infectious complication or prolonged POI.

The DPOI group was older at surgery and were more likely to have previous abdominal surgery, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (47.8±11.5 vs 42.4±13.9 years,

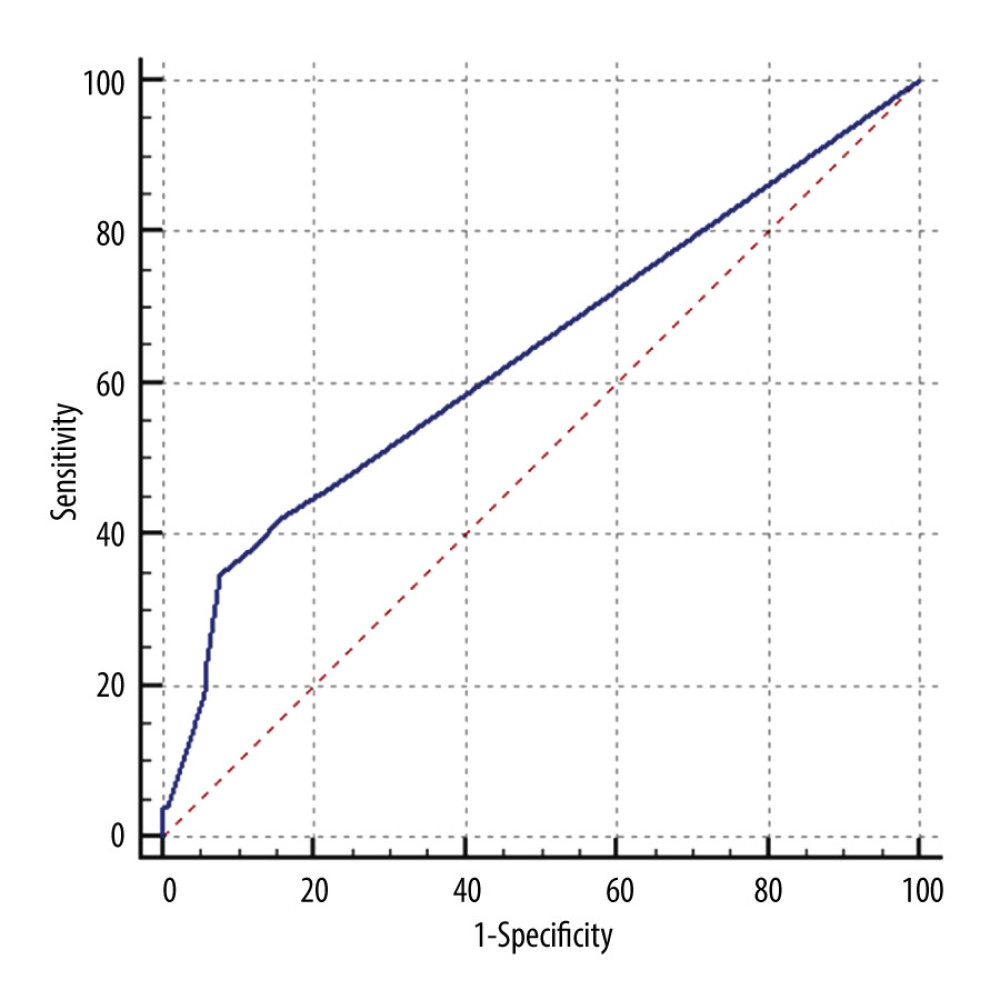

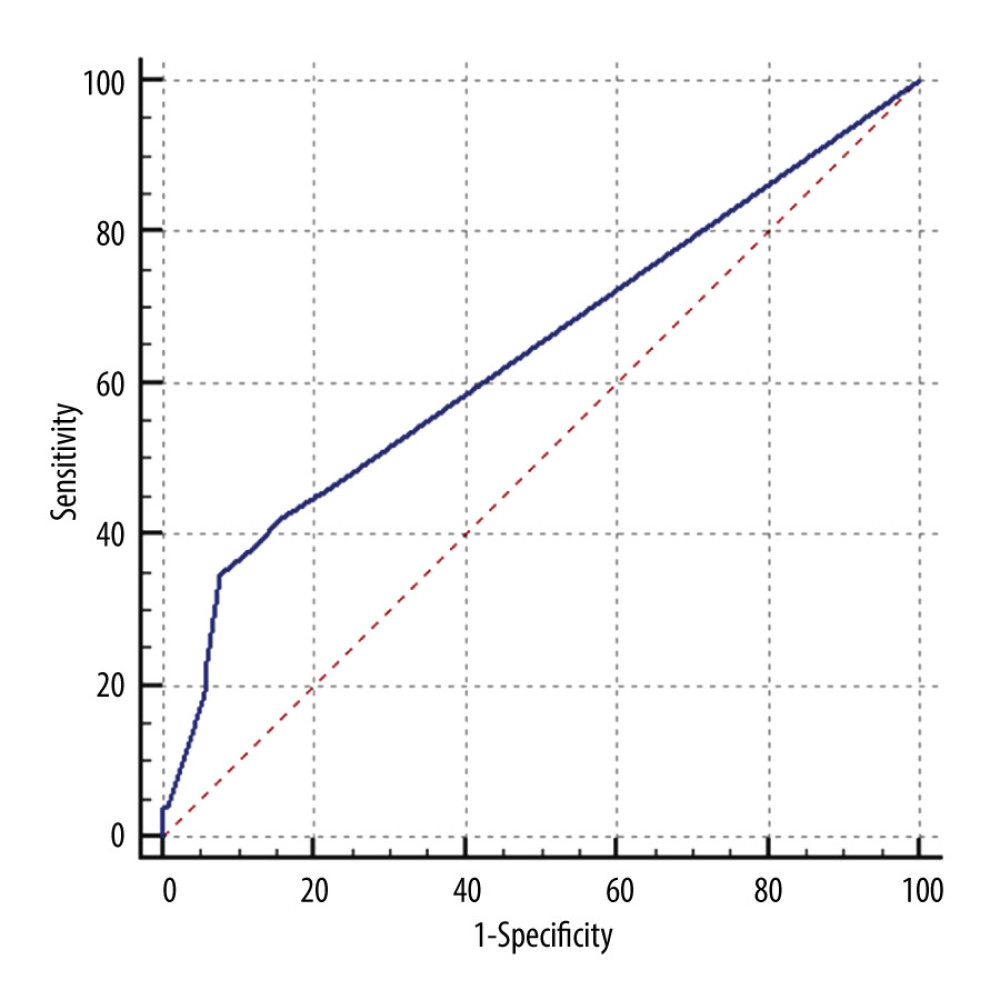

Multivariate analysis confirmed that biologics treatment prior to surgery increased the risk of DPOI by 3-fold (OR 3.100 95% CI 1.261–7.619, P=0.018). For patients who received preoperative biologics, those who developed DPOI had significantly more sessions/courses than those who did not receive preoperative biologics: 4 (range, 1–13) vs 3 (range, 1–10), P=0.024. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showed the number of preoperative biologics session moderately predicted the occurrence of DPOI (area under curve 0.639, 95% CI=0.578–0.697, P=0.0129, sensitivity=0.346, specificity=0.924, cutoff value=4) (Figure 2).

Discussion

The rate of postoperative complication after UC surgery is higher than for other colorectal diseases due to poor nutritional status, preoperative medication, and aberrant immune and inflammatory status [15–17]. Our previous data indicated that colectomy for IBD was associated with higher incidence of prolonged POI compared with colorectal cancer [18]. Here, we described a distinct clinical syndrome that involved 3 pathophysiological phases: ileus, dysbiosis, and recovery. A new term – “delayed postoperative ileus (DPOI)” – was used to specify this syndrome, and our data revealed preoperative biologics exposure was an independent risk factor for DPOI.

The terminology used to describe POI lacks global standardization, with little discrimination being made between the normal obligatory period of gastrointestinal dysmotility and the more clinically significant entity of prolonged or delayed POI [19]. According to a previous systematic review, POI that persists over 4 days postoperatively is regarded as PPOI [5]. In the present study, DPOI refers to those who developed a second episode of ileus with or without PPOI. Our data showed that DPOI was not associated with PPOI, which agrees with a previous study showing that a history of POI from first-stage IPAA could not predict POI after second-stage IPAA [20].

Reviews of the POI pathophysiology emphasize surgical insult as a causal agent that initiates a stress response of both an endocrine and an inflammatory nature, affecting bowel motility [21,22]. Thus, factors that potentially exacerbate the stress response (eg, older age, emergent surgery, operation time) are reported to prolong POI [23,24]. In casesof DPOI, it seems irrational that surgical stress persists to cause relapse of ileus days after discharge. Indeed, our data showed that none of the suggested factors of POI were related to DPOI, indicating a distinct pathogenesis. Our data showed that only preoperative anti-TNF combined with vedolizumab was significantly associated with DPOI (

The mechanisms by which biologics exposure independently influence DPOI are not immediately obvious but are undoubtedly complex and related to the disturbed immune microenvironment. Given that all cases of DPOI were complicated with prominent enteric infection, aberrant host-microbe interaction and dysbiosis might play a pivotal role in its etiology. Previous studies have shown that bacterial translocation is associated with lower response rates to biologics and need for intensified biological therapy [25,26]. In the context of surgery, patients are most likely to receive excessive biologics due to unsatisfactory efficacy rather than due to sequential maintenance therapy. One could reasonably infer that the patients with preoperative biologics (especially those with intensified therapeutic regimen) are more likely to have concurrent bacterial translocation into extraintestinal sites (eg, blood, mesentery, lymph nodes). These resident bacteria might act as opportunistic pathogens that subsequently reciprocally influence the luminal microbiota, leading to dysbiosis and enteric infection in susceptible individuals. In this regard, dysbiosis might be the primary disease of DPOI causing an abrupt increase of intestinal fluids and gastrointestinal dysmotility.

Although the colon and rectum are the most affected organs, it is well acknowledged that UC can display inflammation in other bowel segments as well. Terminal ileum of UC could have villous and crypt architectural distortion with basal lymphoplasmacytosis, cryptitis, and reactive epithelial changes, mimicking the appearance of the colon in UC [27]. Similar histological changes were also found in the stomach [28] and duodenum [29]. Additionally, 2 DPOI cases in our cohort that failed to respond to conservative treatment were diagnosed with UCRSE, which were proved to have proximal enteritis. This indicates continued mucosal inflammation and ulcer in certain UC patients after proctocolectomy, which might be another cause of postoperative ileus and enteric infection.

Certain limitations must be considered when interpreting our results. First, our study might have been underpowered due to the relatively small number of DPOI cases. Second, the study was limited by its retrospective nature, without further exploring the underlying mechanisms of the DPOI syndrome. For example, we were unable to determine whether bacterial translocation importantly participated in the etiology of DPOI. Finally, the DPOI syndrome reported in this study was an original concept we developed, and our conclusions were based on our single-center experience. Further external validation or multi-center studies are warranted to confirm whether DPOI is an overlooked universal phenomenon of UC or an idiopathic syndrome limited to our center.

Conclusions

We observed a distinct pattern of complication after colectomy for UC, characterized by delayed ileus and enteric infection from a high-volume IBD center, which was associated with intensified preoperative biologics exposure. Clarification of this syndrome complemented the spectrum of post-IPAA complications and offered experience that may be useful in treating this condition. Treatment for DPOI including nil per os, somatostatin/octreotide use, and oral antibiotics (vancomycin or rifaximin) was effective.

Figures

Figure 1. Dynamic change of ileostomy output after DPOI diagnosis. Data were derived from DPOI cases that responded to conservative treatment (N=24). Day 0 referred to the last 24 h that constituted the diagnosis of DPOI. * Commencing treatment of somatostatin/octreotide and oral antibiotics.

Figure 1. Dynamic change of ileostomy output after DPOI diagnosis. Data were derived from DPOI cases that responded to conservative treatment (N=24). Day 0 referred to the last 24 h that constituted the diagnosis of DPOI. * Commencing treatment of somatostatin/octreotide and oral antibiotics.  Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristics curve of biologics sessions/courses to predict DPOI. (Area under curve 0.639, 95% CI=0.578–0.697, P=0.0129, sensitivity=0.346, specificity=0.924, cutoff value=4).

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristics curve of biologics sessions/courses to predict DPOI. (Area under curve 0.639, 95% CI=0.578–0.697, P=0.0129, sensitivity=0.346, specificity=0.924, cutoff value=4). References

1. Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Hanauer SB, Ulcerative colitis: BMJ, 2013; 346; f432

2. Magro F, Rodrigues A, Vieira AI, Review of the disease course among adult ulcerative colitis population-based longitudinal cohorts: Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2012; 18(3); 573-83

3. Danese S, Fiocchi C, Ulcerative colitis: N Engl J Med, 2011; 365(18); 1713-25

4. SSommer NP, Schneider R, Wehner S, State-of-the-art colorectal disease: Postoperative ileus: Int J Colorectal Dis, 2021; 36(9); 2017-25

5. Vather R, Trivedi S, Bissett I, Defining postoperative ileus: Results of a systematic review and global survey: J Gastrointest Surg, 2013; 17(5); 962-72

6. Scarborough JE, Schumacher J, Kent KC, Associations of specific postoperative complications with outcomes after elective colon resection: A procedure-targeted approach toward surgical quality improvement: JAMA Surg, 2017; 152(2); e164681

7. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Germain A, Patel AS, Systematic review: Outcomes and post-operative complications following colectomy for ulcerative colitis: Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2016; 44(8); 807-16

8. Kim JY, Zaghiyan K, Lightner A, Risk of postoperative complications among ulcerative colitis patients treated preoperatively with vedolizumab: A matched case-control study: BMC Surg, 2020; 20(1); 46

9. Bregnbak D, Mortensen C, Bendtsen F, Infliximab and complications after colectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis: J Crohns Colitis, 2012; 6(3); 281-86

10. Xu Y, Yang L, An P, Meta-analysis: The influence of preoperative infliximab use on postoperative complications of Crohn’s disease: Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2019; 25(2); 261-69

11. Lightner AL, McKenna NP, Tse CS, Postoperative outcomes in ustekinumab-treated patients undergoing abdominal operations for Crohn’s disease: J Crohns Colitis, 2018; 12(4); 402-7

12. Kotze PG, Magro DO, Martinez CAR, Adalimumab and postoperative complications of elective intestinal resections in Crohn’s disease: A propensity score case-matched study: Colorectal Dis, 2017 [Online ahead of print]

13. Kohyama A, Watanabe K, Sugita A, Ulcerative colitis-related severe enteritis: An infrequent but serious complication after colectomy: J Gastroenterol, 2021; 56(3); 240-49

14. Shimoda F, Kuroha M, Chiba H, Ulcerative colitis-related postoperative enteritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: Two case reports and a literature review: Clin J Gastroenterol, 2021; 14(5); 1396-403

15. Law CC, Bell C, Koh D, Risk of postoperative infectious complications from medical therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2020; 10(10); CD013256

16. Xie T, Zhao C, Ding C, Postoperative interleukin-6 predicts intra-abdominal septic complications at an early stage after elective intestinal operation for Crohn’s disease patients: Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2018; 24(9); 1992-2000

17. Zhu F, Li Y, Guo Z, Nomogram to predict postoperative intra-abdominal septic complications after bowel resection and primary anastomosis for Crohn’s disease: Dis Colon Rectum, 2020; 63(5); 629-38

18. Dai X, Ge X, Yang J, Increased incidence of prolonged ileus after colectomy for inflammatory bowel diseases under ERAS protocol: A cohort analysis: J Surg Res, 2017; 212; 86-93

19. Grass F, Slieker J, Jurt J, Postoperative ileus in an enhanced recovery pathway – a retrospective cohort study: Int J Colorectal Dis, 2017; 32(5); 675-81

20. Le Q, Liou DZ, Murrell Z, Does a history of postoperative ileus predispose to recurrent ileus after multistage ileal pouch-anal anastomosis?: Tech Coloproctol, 2013; 17(4); 383-88

21. Holte K, Kehlet H, Postoperative ileus: A preventable event: Br J Surg, 2000; 87(11); 1480-93

22. Chapman SJ, Pericleous A, Downey C, Jayne DG, Postoperative ileus following major colorectal surgery: Br J Surg, 2018; 105(7); 797-810

23. Koch KE, Hahn A, Hart A, Male sex, ostomy, infection, and intravenous fluids are associated with increased risk of postoperative ileus in elective colorectal surgery: Surgery, 2021; 170(5); 1325-30

24. Chapuis PH, Bokey L, Keshava A, Risk factors for prolonged ileus after resection of colorectal cancer: An observational study of 2400 consecutive patients: Ann Surg, 2013; 257(5); 909-15

25. Gutiérrez A, Scharl M, Sempere L, Genetic susceptibility to increased bacterial translocation influences the response to biological therapy in patients with Crohn’s disease: Gut, 2014; 63(2); 272-80

26. Gutiérrez A, Zapater P, Juanola O, Gut bacterial DNA translocation is an independent risk factor of flare at short term in patients with Crohn’s disease: Am J Gastroenterol, 2016; 111(4); 529-40

27. Patil DT, Odze RD, Backwash is hogwash: The clinical significance of ileitis in ulcerative colitis: Am J Gastroenterol, 2017; 112(8); 1211-14

28. Lin J, McKenna BJ, Appelman HD, Morphologic findings in upper gastrointestinal biopsies of patients with ulcerative colitis: A controlled study: Am J Surg Pathol, 2010; 34(11); 1672-77

29. Valdez R, Appelman HD, Bronner MP, Diffuse duodenitis associated with ulcerative colitis: Am J Surg Pathol, 2000; 24(10); 1407-13

Figures

Figure 1. Dynamic change of ileostomy output after DPOI diagnosis. Data were derived from DPOI cases that responded to conservative treatment (N=24). Day 0 referred to the last 24 h that constituted the diagnosis of DPOI. * Commencing treatment of somatostatin/octreotide and oral antibiotics.

Figure 1. Dynamic change of ileostomy output after DPOI diagnosis. Data were derived from DPOI cases that responded to conservative treatment (N=24). Day 0 referred to the last 24 h that constituted the diagnosis of DPOI. * Commencing treatment of somatostatin/octreotide and oral antibiotics. Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristics curve of biologics sessions/courses to predict DPOI. (Area under curve 0.639, 95% CI=0.578–0.697, P=0.0129, sensitivity=0.346, specificity=0.924, cutoff value=4).

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristics curve of biologics sessions/courses to predict DPOI. (Area under curve 0.639, 95% CI=0.578–0.697, P=0.0129, sensitivity=0.346, specificity=0.924, cutoff value=4). Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the enrolled patients (n=263).

Table 1. Characteristics of the enrolled patients (n=263). Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with DPOI.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with DPOI. Table 1. Characteristics of the enrolled patients (n=263).

Table 1. Characteristics of the enrolled patients (n=263). Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with DPOI.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with DPOI. Supplementary Table 1. Summary of infectious complications in the cohort.

Supplementary Table 1. Summary of infectious complications in the cohort. In Press

07 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 179 Male Third- and Fourt...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943468

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952