12 March 2024: Clinical Research

Effect of Body Mass Index on Cecal Intubation Time During Unsedated Colonoscopy: Variation Across the Learning Stages of an Endoscopist

Cong Gao12ABCEF, Deli Zou1E, Rongrong Cao1E, Yingchao Li1B, Dongshuai Su1B, Jie Han1B, Fei Gao1E, Xingshun Qi1ABCDEF*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942661

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942661

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Body mass index (BMI) and endoscopists’ experiences can be associated with cecal intubation time (CIT), but such associations are controversial. This study aimed to clarify the association between BMI and CIT during unsedated colonoscopy at 3 learning stages of a single endoscopist.

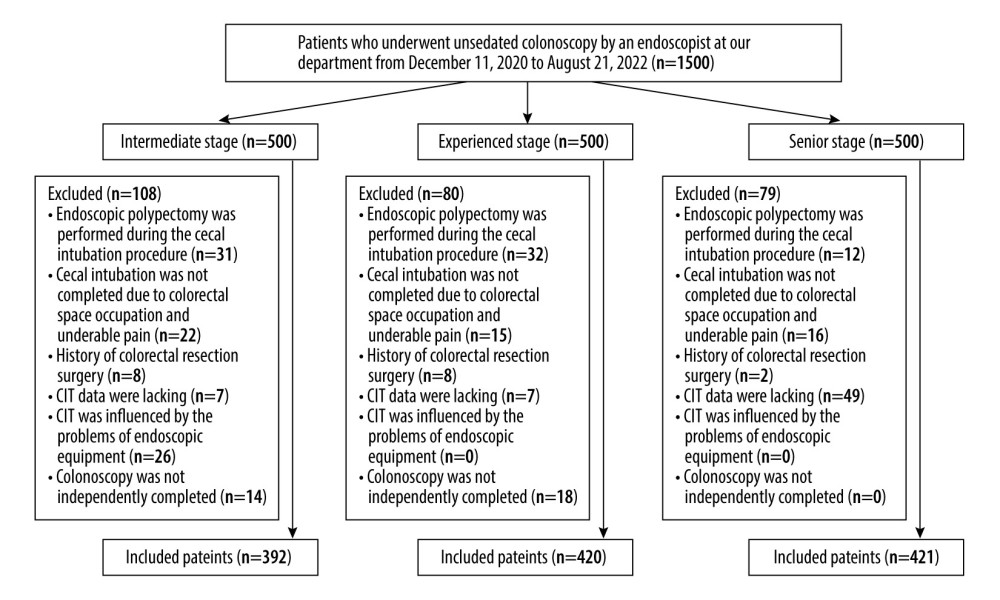

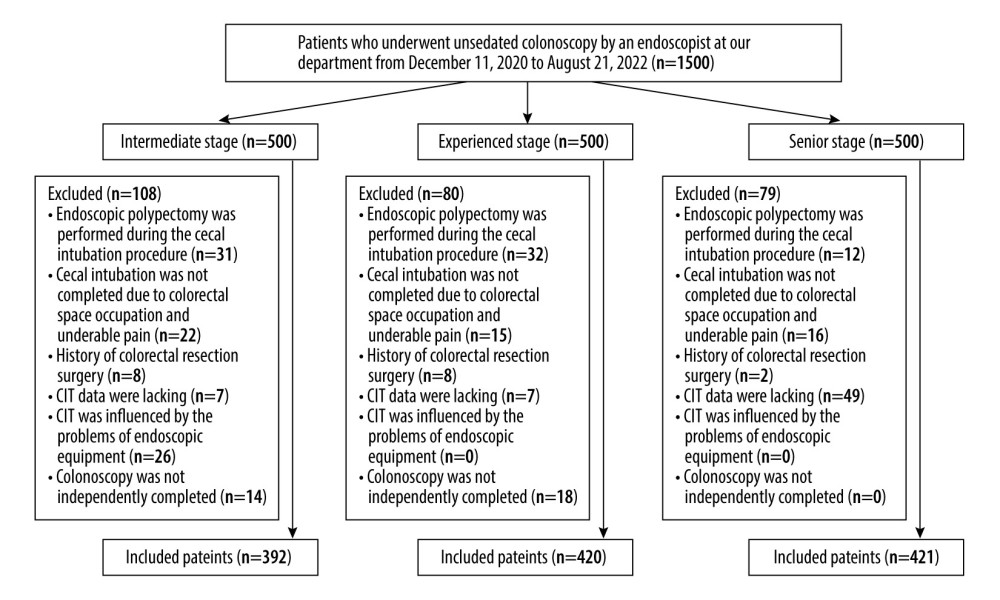

MATERIAL AND METHODS: A total of 1500 consecutive patients undergoing unsedated colonoscopy by 1 endoscopist at our department from December 11, 2020, to August 21, 2022, were reviewed. They were divided into 3 learning stages according to the number of colonoscopies performed by 1 endoscopist, including intermediate (501-1000 colonoscopies), experienced (1001-1500 colonoscopies), and senior stages (1501-2000 colonoscopies). Variables that significantly correlated with CIT were identified by Spearman rank correlation analyses and then included in multiple linear regression analysis.

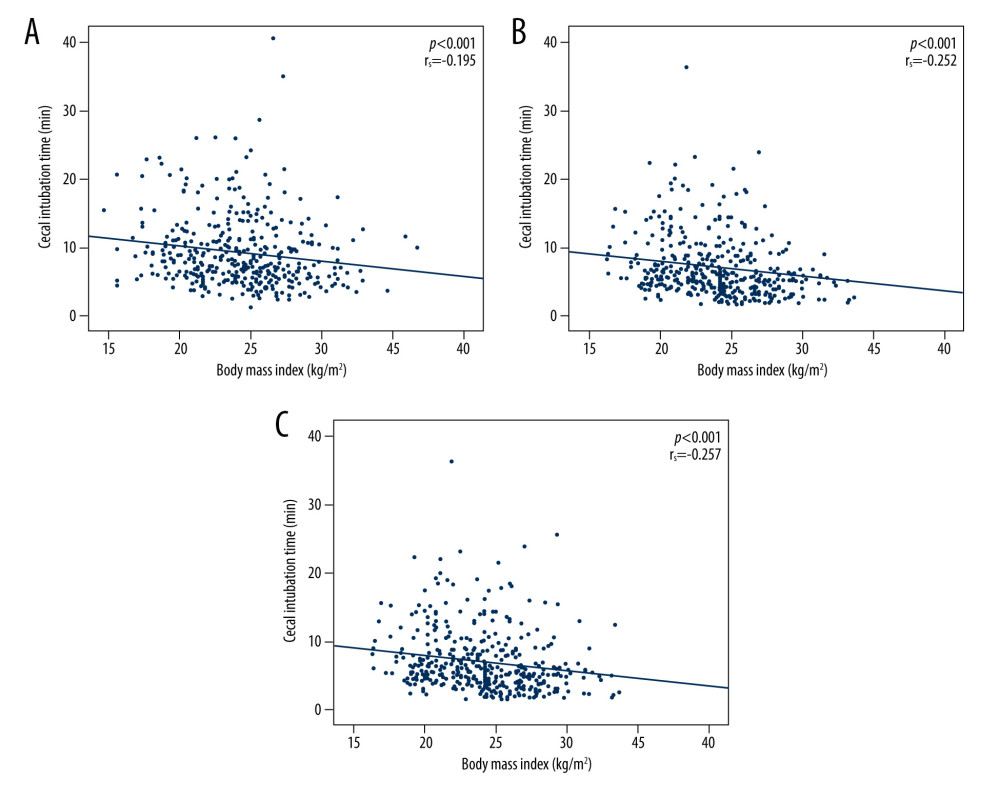

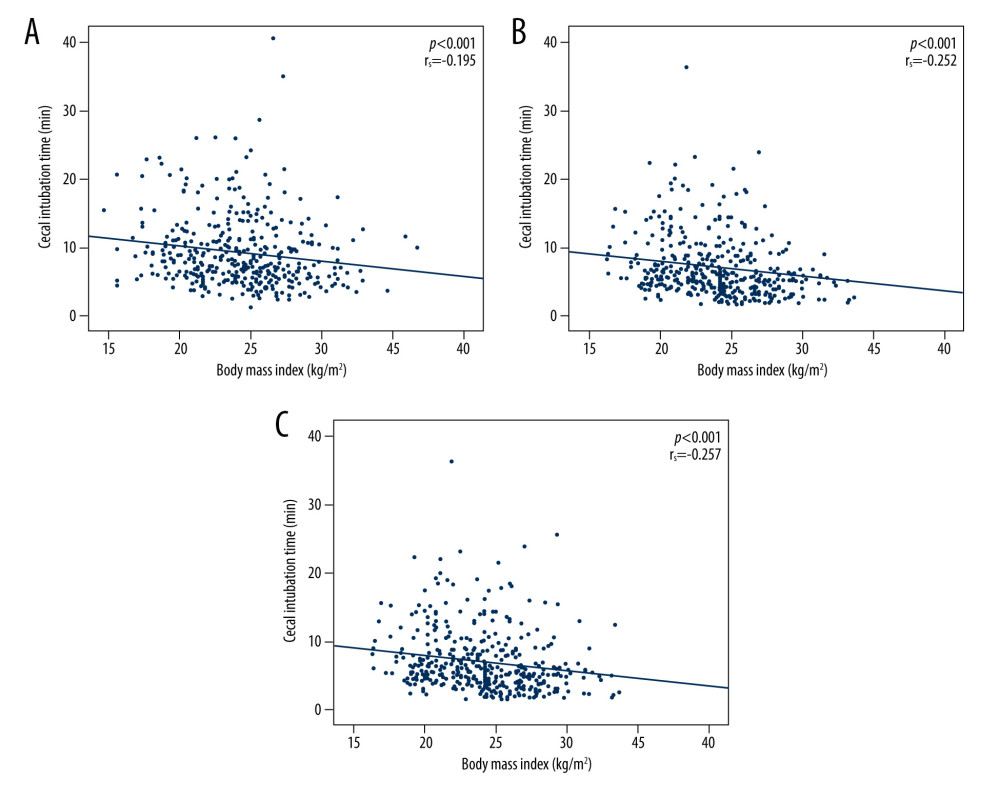

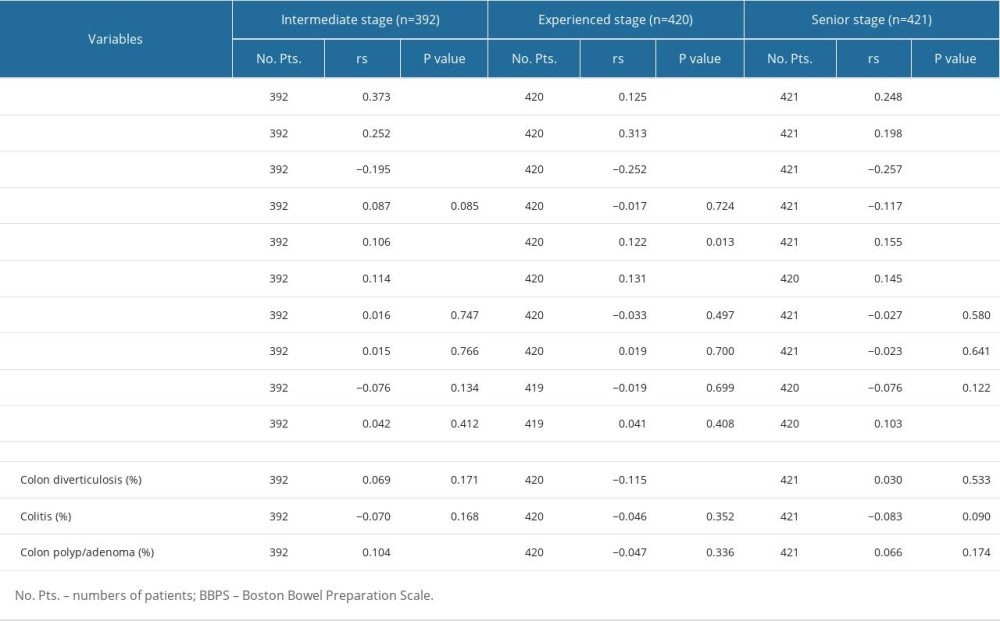

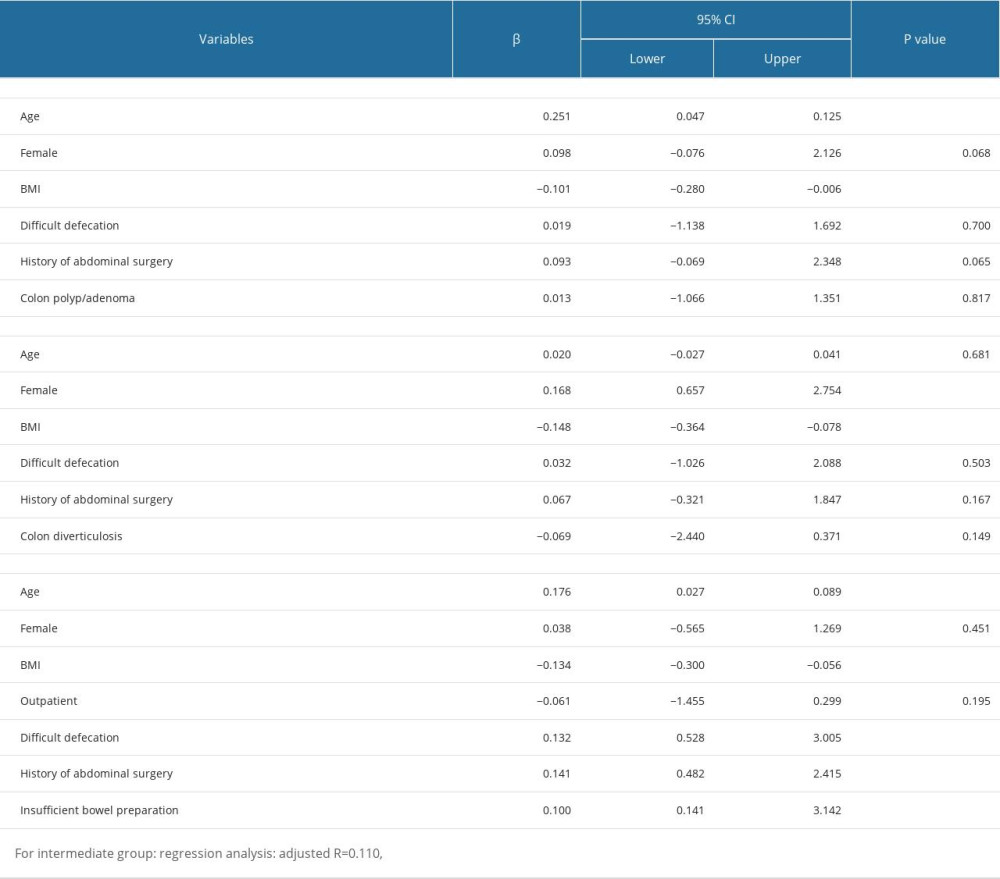

RESULTS: Overall, 1233 patients were included. Among them, 392, 420, and 421 patients were divided into intermediate, experienced, and senior stages, respectively. Median CIT was 7.83, 6.38, and 5.58 min at intermediate, experienced, and senior stages, respectively (P<0.001). BMI was negatively correlated with CIT at the 3 stages (intermediate stage: rₛ=-0.195, P<0.001; experienced stage: rₛ=-0.252, P<0.001; senior stage: rₛ=-0.257, P<0.001), and multiple linear regression analyses demonstrated that a lower BMI predicted a longer CIT at the 3 stages (intermediate stage: β=-0.101, P=0.041; experienced stage: β=-0.148, P=0.002; senior stage: β=-0.134, P=0.004).

CONCLUSIONS: Regardless of an endoscopist’s experience, there is a negative correlation between BMI and CIT. A lower BMI might be an indicator of difficult colonoscopy, suggesting that experienced endoscopists should be invited to perform colonoscopy in the lean population.

Keywords: Body Mass Index, Colonoscopy, Intubation, Gastrointestinal

Background

Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Each year, colorectal cancer is newly diagnosed in more than 1.9 million patients and causes nearly 935 000 deaths, according to the global cancer statistics [2]. Adenomatous polyps are major precursors for colorectal cancer, which are usually detected and then removed during colonoscopy [3]. Therefore, screening colonoscopy has been recommended to reduce the incidence of colorectal cancer [4–7].

Cecal intubation (CI) is an important factor for evaluating the quality of colonoscopy, and successful CI is a prerequisite of complete colonoscopy [8]. Cecal intubation time (CIT) can be used to measure the difficulty of colonoscopy [9]. Some previous studies showed that CIT might be affected by body mass index (BMI) [10–12]. Patients with a lower BMI often had longer CIT during colonoscopy [13–15]. However, other studies demonstrated that BMI was not significantly associated with CIT [16,17]. Such a controversy may be related to the heterogeneity in the patients’ characteristics, endoscopists’ experiences, and types of colonoscopy (sedated or unsedated) among studies. Notably, experienced endoscopists often have shorter CIT and lower subjective difficulty of colonoscopy [18–20]. However, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have evaluated the effect of BMI on CIT at the different learning stages of an endoscopist. We conducted this retrospective observational study to further clarify the association between BMI and CIT by collecting the data of unsedated colonoscopy conducted by the same endoscopist at his different stages of learning.

Material and Methods

STUDY DESIGN:

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 1500 patients undergoing unsedated colonoscopy by the same endoscopist at our department from December 11, 2020, to August 21, 2022. He had completed a total of 500 colonoscopy procedures before the enrollment period. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) endoscopic polypectomy was performed during the CI procedure; (2) cecal intubation was not completed due to colorectal occupation or unbearable pain; (3) patients had a history of colorectal resection surgery; (4) CIT data was lacking; (5) colonoscopy was not independently completed by the endoscopist; and (6) CIT was influenced by the problems of endoscopic equipment. This retrospective observational study followed the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and obtained the approval of the Medical Ethical Committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command (Y [2023] 009). Written informed consent was waived due to the nature of this study.

DATA COLLECTION:

We collected the information regarding demographic data (eg, sex and age), height, weight, outpatient or inpatient, colonoscopy performed in the morning or afternoon, history of abdominal surgery, history of colonoscopy, difficult defecation as the major complaint, major colonoscopic findings (ie, colonic diverticulosis, colitis, and polyp/adenoma), CIT, and Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) score [21]. BMI was calculated. Data accuracy was checked by 3 investigators.

DEFINITIONS:

Patients were defined as underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5≤ BMI <25.0 kg/m2), overweight (25.0≤ BMI <30 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), respectively [22].

CIT was defined as the time from the anus to the cecum during colonoscopy [23].

Sufficient bowel preparation was defined as a total BBPS score of ≥6, with a BBPS score of ≥2 per colon segment [24].

As far as we know, there is no consensus regarding how to define the different learning stages of an endoscopist according to the number of colonoscopies performed. Considering that previous definitions are arbitrary [25], our study defined each 500 colonoscopies as 1 individual stage. Notably, the first 500 colonoscopies performed by this endoscopist before this study was defined as the novice stage, which were not enrolled in our study. The latter 1500 colonoscopies performed by this endoscopist were included in this study and were divided into intermediate stage (501–1000 colonoscopies), experienced stage (1001–1500 colonoscopies), and senior stage (1501–2000 colonoscopies).

BOWEL PREPARATION AND COLONOSCOPY PROCEDURES:

All patients received a split dose of 3 L polyethylene glycol (PEG) for bowel preparation, according to the current practice guideline [26]. Patients were instructed to drink 1 L PEG 2 h after dinner the night before colonoscopy, and then the remaining 2 L PEG and 30 mL simethicone the morning of the colonoscopy. In addition, patients were instructed to perform a slag-free diet the day before colonoscopy. During unsedated colonoscopy, lidocaine hydrochloride gel was used on the anus. All colonoscopies were performed by the Fujinon colonoscopes (EC-530WM, EC-450WI5, or EC-250WM5, Japan). The type of colonoscope was different among examination rooms of our department. Because the endoscopist regularly took turns to different examination rooms for performing colonoscopy procedures, he used different types of colonoscopes in our study.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES:

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation and median (range), and nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test and analysis of variance were used for comparative analyses. Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (percentage), and chi-square tests were used for comparative analyses. Variables that significantly correlated with CIT were identified by Spearman rank correlation analyses and then were included in a multiple linear regression analysis. A 2-tailed

Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS:

Overall, 1233 patients were included (Figure 1). Among them, 392, 420, and 421 patients were divided into intermediate, experienced, and senior stages, respectively. Patient median age was 55, 52, and 55 years, respectively; 48.2% (189/392), 46.9% (197/420), and 43.7% (184/421) patients were female, respectively; the median BMI was 24.40, 23.90, and 24.20 kg/m2, respectively; the proportion of history of abdominal surgery was 25.0% (98/392), 27.9% (117/420), and 28.6% (120/420), respectively; the proportion of insufficient bowel preparation was 11.7% (46/392), 7.9% (33/420), and 8.8% (37/420), respectively; and the median CIT was 7.83, 6.38, and 5.58 min, respectively (Table 1). The proportions of outpatient, colitis, and CIT were significantly different among the 3 stages.

CORRELATION BETWEEN BMI AND CIT AT INTERMEDIATE STAGE:

BMI was negatively correlated with CIT at the intermediate stage (rs=−0.195, P<0.001) (Figure 2A). However, age (rs=0.373, P<0.001), female sex (rs=0.252, P<0.001), difficult defecation (rs=0.106, P=0.039), history of abdominal surgery (rs=0.114, P=0.025), and colon polyp/adenoma (rs=0.104, P=0.040) were positively correlated with CIT (Table 2).

After adjusting for age, female sex, BMI, difficult defecation, history of abdominal surgery, and colon polyp/adenoma, multiple linear regression analyses demonstrated that a lower BMI still predicted a longer CIT at the intermediate stage (β=−0.101, P=0.041) (Table 3).

CORRELATION BETWEEN BMI AND CIT AT EXPERIENCED STAGE:

BMI was negatively correlated with CIT at the experienced stage (rs=−0.252, P<0.001) (Figure 2B). Also, colon diverticulosis (rs=−0.115, P=0.018) was negatively correlated with CIT. However, age (rs=0.125, P=0.010), female sex (rs=0.313, P<0.001), difficult defecation (rs=0.122, P=0.013), and history of abdominal surgery (rs=0.131, P=0.007) were positively correlated with CIT (Table 2).

After adjusting for age, female sex, BMI, difficult defecation, history of abdominal surgery, and colon diverticulosis, multiple linear regression analyses demonstrated that a lower BMI still predicted a longer CIT at the experienced stage (β=−0.148, P=0.002) (Table 3).

CORRELATION BETWEEN BMI AND CIT AT SENIOR STAGE:

BMI was negatively correlated with CIT at the senior stage (rs=−0.257, P<0.001) (Figure 2C). Also, outpatient (rs=−0.117, P=0.016) was negatively correlated with CIT. However, age (rs=0.248, P<0.001), female sex (rs=0.198, P<0.001), difficult defecation (rs=0.155, P=0.001), history of abdominal surgery (rs=0.145, P=0.003), and insufficient bowel preparation (rs=0.103, P=0.034) were positively correlated with CIT (Table 2).

After adjusting for age, female sex, BMI, outpatient, difficult defecation, history of abdominal surgery, and insufficient bowel preparation, multiple linear regression analyses demonstrated that a lower BMI still predicted a longer CIT at the senior stage (β=−0.134, P=0.004) (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study showed that BMI was negatively correlated with CIT at the intermediate, experienced, and senior learning stages of the endoscopist, and such a correlation was further validated by multiple linear regression analyses. These findings further confirmed the correlation of lower BMI with longer CIT. There are some possible explanations, as follows. First, patients with overweight often have more intra-abdominal fat, which can be used for supporting the colon, causing fewer loops and then shortening CIT during colonoscopy [12,27]. Second, patients with overweight often have shorter colons than those who have normal weight or are thin, probably facilitating the CI procedure [28]. Third, thinner patients often have sharper colonic angulation, causing more pain, which increases the difficulty of CI and prolongs CIT during unsedated colonoscopy [29].

During our study period, the endoscopist’s experience improved from the intermediate to senior stage, and the outcomes were separately evaluated across these different stages to further explore the reliability of our statistical results. This is because the endoscopist’s experience in screening colonoscopy is often directly related to the CIT and degree of patients’ pain [30–33]. First, increased experience of the endoscopist closely correlates with decreased CIT [18,19]. Patwardhan et al found that the mean CIT gradually decreased over the duration of endoscopists’ training (1-year training: 13.29 min; 2-year training: 8.79 min; and 3-year training: 5.14 min; P<0.001) [34]. Similarly, we also found that the mean CIT was negatively associated with the number of colonoscopies performed by the endoscopist (intermediate stage: 9.30 min; experienced stage: 8.03 min; and senior stage: 7.01 min;

There are many methods for shortening CIT in patients with lower BMI. First, in the lean population, loops frequently develop in the sigmoid colon and the hepatic flexure during colonoscopy, which can prolong CIT [36]. Previous studies showed that abdominal compression was a useful ancillary maneuver to remove and reduce the formation of loops in the sigmoid colon and hepatic flexure during colonoscopy, and there are some methods of abdominal compression, including hand pressure and use of an abdominal corset [37,38]. Second, in the lean population, sharp colon angulation tends to be more common, and these angulations can interfere with smooth colonoscopy insertion [29]. A position change from the left lateral position to the supine position can facilitate the colonoscope passing the rectosigmoid junction, a position change to the right lateral position can facilitate the colonoscope passing the splenic flexure, and a position change back to the left lateral position can facilitate the colonoscope passing hepatic flexure [36]. Therefore, position changes can be helpful for shortening CIT. Third, the presence of loops can cause spasm and pain, compromising the CI procedure. Instillation of warm water in the colon during the early phase of colonoscope insertion can straighten the sigmoid colon and open the sigmoid-descending junction by the weight of the water. It can also relieve patients’ pain by the heat of water [39], thereby simplifying the CI procedure.

Our study has several major features. First, we separately explored the correlation of BMI with CIT at intermediate, experienced, and senior stages of the endoscopist, which strengthened the reliability of our statistical results. Second, our study was the first to explore the effect of BMI on CIT by the same endoscopist, which could avoid the heterogeneity caused by including different endoscopists. Third, the conclusion was verified by multiple regression analysis, which further confirmed a negative correlation between BMI and CIT. Fourth, all relevant data were prospectively recorded, which could ensure their completeness.

There were some limitations in our study. First, we subjectively defined each 500 colonoscopies as 1 individual stage. Second, this was a retrospective study, which needs to be validated in a prospective trial. Third, the patients’ pain tolerance was not graded and compared in the present study. Fourth, many patients were excluded due to the problem of endoscopic equipment at the intermediate stage.

Conclusions

CIT gradually decreased as the endoscopist became more experienced. There was still a negative correlation between BMI and CIT at the endoscopist’s different learning stages, suggesting that BMI should be a predictor for difficult cecal intubation during colonoscopy. However, it should be further validated in prospective studies.

Figures

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients’ enrollment at each stage. Figure 1 was made by PowerPoint software version 2019 (Microsoft).

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients’ enrollment at each stage. Figure 1 was made by PowerPoint software version 2019 (Microsoft).  Figure 2. Scattered diagrams showing the correlation of cecal intubation time with body mass index at the endoscopist’s intermediate stage (A), experienced stage (B), and senior stage (C). Figures were made by IBM SPSS software version 20.0 (IBM Corp).

Figure 2. Scattered diagrams showing the correlation of cecal intubation time with body mass index at the endoscopist’s intermediate stage (A), experienced stage (B), and senior stage (C). Figures were made by IBM SPSS software version 20.0 (IBM Corp). References

1. Biller LH, Schrag D, Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A review: JAMA, 2021; 325; 669-85

2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries: CA Cancer J Clin, 2021; 71; 209-49

3. Moore JS, Aulet TH, Colorectal cancer screening: Surg Clin North Am, 2017; 97; 487-502

4. Saito Y, Oka S, Kawamura T, Colonoscopy screening and surveillance guidelines: Dig Endosc, 2021; 33; 486-519

5. Bretthauer M, Løberg M, Wieszczy P, Effect of colonoscopy screening on risks of colorectal cancer and related death: New Engl J Med, 2022; 387; 1547-56

6. Gupta S, Screening for colorectal cancer: Hematol Oncol Clin North Am, 2022; 36; 393-414

7. Lam TH, Wong KH, Chan KK, Recommendations on prevention and screening for colorectal cancer in Hong Kong: Hong Kong Med J, 2018; 24; 521-26

8. Shine R, Bui A, Burgess A, Quality indicators in colonoscopy: An evolving paradigm: ANZ J Surg, 2020; 90; 215-21

9. Jia H, Wang L, Luo H, Difficult colonoscopy score identifies the difficult patients undergoing unsedated colonoscopy: BMC Gastroenterol, 2015; 15; 46

10. Jaruvongvanich V, Sempokuya T, Laoveeravat P, Ungprasert P, Risk factors associated with longer cecal intubation time: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Int J Colorectal Dis, 2018; 33; 359-65

11. Jain D, Goyal A, Uribe J, Obesity and cecal intubation time: Clin Endosc, 2016; 49; 187-90

12. Krishnan P, Sofi AA, Dempsey R, Body mass index predicts cecal insertion time: the higher, the better: Dig Endosc, 2012; 24; 439-42

13. Yilmaz S, Bolukbasi H, Bozkurt MA, Factors effecting cecal intubation time during colonoscopy: Ann Ital Chir, 2021; 92; 665-70

14. Chung GE, Lim SH, Yang SY, Factors that determine prolonged cecal intubation time during colonoscopy: Impact of visceral adipose tissue: Scand J Gastroenterol, 2014; 49; 1261-67

15. Karapolat B, Kucuktulu U, Effects of body mass index on cecal intubation time in women: Turk J Surg, 2018; 34; 94-96

16. Kim HY, Cecal intubation time in screening colonoscopy: Medicine (Baltimore), 2021; 100; e25927

17. Arcovedo R, Larsen C, Reyes HS, Patient factors associated with a faster insertion of the colonoscope: Surg Endosc, 2007; 21; 885-88

18. Harewood GC, Relationship of colonoscopy completion rates and endoscopist features: Dig Dis Sci, 2005; 50; 47-51

19. Chak A, Cooper GS, Blades EW, Prospective assessment of colonoscopic intubation skills in trainees: Gastrointest Endosc, 1996; 44; 54-57

20. Park HJ, Hong JH, Kim HS, Predictive factors affecting cecal intubation failure in colonoscopy trainees: BMC Med Educ, 2013; 13; 5

21. Calderwood AH, Schroy PC, Lieberman DA, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale scores provide a standardized definition of adequate for describing bowel cleanliness: Gastrointest Endosc, 2014; 80; 269-76

22. Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH, Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity: JAMA, 2005; 293; 1861-67

23. Pullens HJ, Siersema PD, Quality indicators for colonoscopy: Current insights and caveats: World J Gastrointest Endosc, 2014; 6; 571-83

24. Kastenberg D, Bertiger G, Brogadir S, Bowel preparation quality scales for colonoscopy: World J Gastroenterol, 2018; 24; 2833-43

25. Scaffidi MA, Grover SC, Carnahan H, A prospective comparison of live and video-based assessments of colonoscopy performance: Gastrointest Endosc, 2018; 87; 766-75

26. Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F, Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline – update 2019: Endoscopy, 2019; 51; 775-94

27. Nagata N, Sakamoto K, Arai T, Predictors for cecal insertion time: The impact of abdominal visceral fat measured by computed tomography: Dis Colon Rectum, 2014; 57; 1213-19

28. Khashab MA, Pickhardt PJ, Kim DH, Rex DK, Colorectal anatomy in adults at computed tomography colonography: Normal distribution and the effect of age, sex, and body mass index: Endoscopy, 2009; 41; 674-78

29. Goksoy B, Kiyak M, Karadag M, Factors affecting cecal intubation time in colonoscopy: Impact of obesity: Cureus, 2021; 13; e15356

30. Muthukuru S, Alomari M, Bisen R, Quality of colonoscopy: A comparison between gastroenterologists and nongastroenterologists: Dis Colon Rectum, 2020; 63; 980-87

31. Chan BPH, Hussey A, Rubinger N, Hookey LC, Patient comfort scores do not affect endoscopist behavior during colonoscopy, while trainee involvement has negative effects on patient comfort: Endosc Int Open, 2017; 5; E1259-E67

32. Zuber-Jerger I, Endlicher E, Gelbmann CM, Factors affecting cecal and ileal intubation time in colonoscopy: Med Klin (Munich), 2008; 103; 477-81

33. Hoff G, Botteri E, Huppertz-Hauss G, The effect of train-the-colonoscopy-trainer course on colonoscopy quality indicators: Endoscopy, 2021; 53; 1229-34

34. Patwardhan VR, Feuerstein JD, Sengupta N, Fellowship colonoscopy training and preparedness for independent gastroenterology practice: J Clin Gastroenterol, 2016; 50; 45-51

35. Bugajski M, Wieszczy P, Hoff G, Modifiable factors associated with patient-reported pain during and after screening colonoscopy: Gut, 2018; 67; 1958-64

36. Rodrigues-Pinto E, Ferreira-Silva J, Macedo G, Rex DK, (Technically) Difficult colonoscope insertion – tips and tricks: Dig Endosc, 2019; 31; 583-87

37. Liu TT, Meng YT, Xiong F, Impact of an abdominal compression bandage on the completion of colonoscopy for obese adults: A prospective randomized controlled trial: Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022; 2022; 6010367

38. Toros AB, Ersoz F, Ozcan O, Does a fitted abdominal corset makes colonoscopy more tolerable?: Dig Endosc, 2012; 24; 164-67

39. Park SC, Keum B, Kim ES, Usefulness of warm water and oil assistance in colonoscopy by trainees: Dig Dis Sci, 2010; 55; 2940-44

Figures

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients’ enrollment at each stage. Figure 1 was made by PowerPoint software version 2019 (Microsoft).

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients’ enrollment at each stage. Figure 1 was made by PowerPoint software version 2019 (Microsoft). Figure 2. Scattered diagrams showing the correlation of cecal intubation time with body mass index at the endoscopist’s intermediate stage (A), experienced stage (B), and senior stage (C). Figures were made by IBM SPSS software version 20.0 (IBM Corp).

Figure 2. Scattered diagrams showing the correlation of cecal intubation time with body mass index at the endoscopist’s intermediate stage (A), experienced stage (B), and senior stage (C). Figures were made by IBM SPSS software version 20.0 (IBM Corp). Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population. Table 2. Correlations between variables and cecal intubation time at the intermediate stage, experienced stage, and senior stage.

Table 2. Correlations between variables and cecal intubation time at the intermediate stage, experienced stage, and senior stage. Table 3. Multiple linear regression analyses of factors of cecal intubation time.

Table 3. Multiple linear regression analyses of factors of cecal intubation time. Table 1. Characteristics of the study population.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population. Table 2. Correlations between variables and cecal intubation time at the intermediate stage, experienced stage, and senior stage.

Table 2. Correlations between variables and cecal intubation time at the intermediate stage, experienced stage, and senior stage. Table 3. Multiple linear regression analyses of factors of cecal intubation time.

Table 3. Multiple linear regression analyses of factors of cecal intubation time. In Press

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952