18 August 2020: Clinical Research

Risk Factors for Acquisition of Carbapenem-Resistant and Mortality Among Abdominal Solid Organ Transplant Recipients with Infections

Di Wu1BCDE, Chunmei Chen2CEF, Taohua Liu3DE, Qiquan Wan1ACDEFG*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.922996

Med Sci Monit 2020; 26:e922996

Abstract

BACKGROUND: For abdominal solid organ transplant (ASOT) recipients, infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae, particularly carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP), can be life-threatening. The aims of this study were to characterize the risk factors associated with acquisition of CRKP and 90-day crude mortality among patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: In our cohort study, we retrospectively reviewed 68 K. pneumoniae-infected transplant recipients, studied their demographics, clinical manifestations, microbiology, and outcomes, and determined the risk factors associated with the occurrence of CRKP and crude mortality due to K. pneumoniae infections.

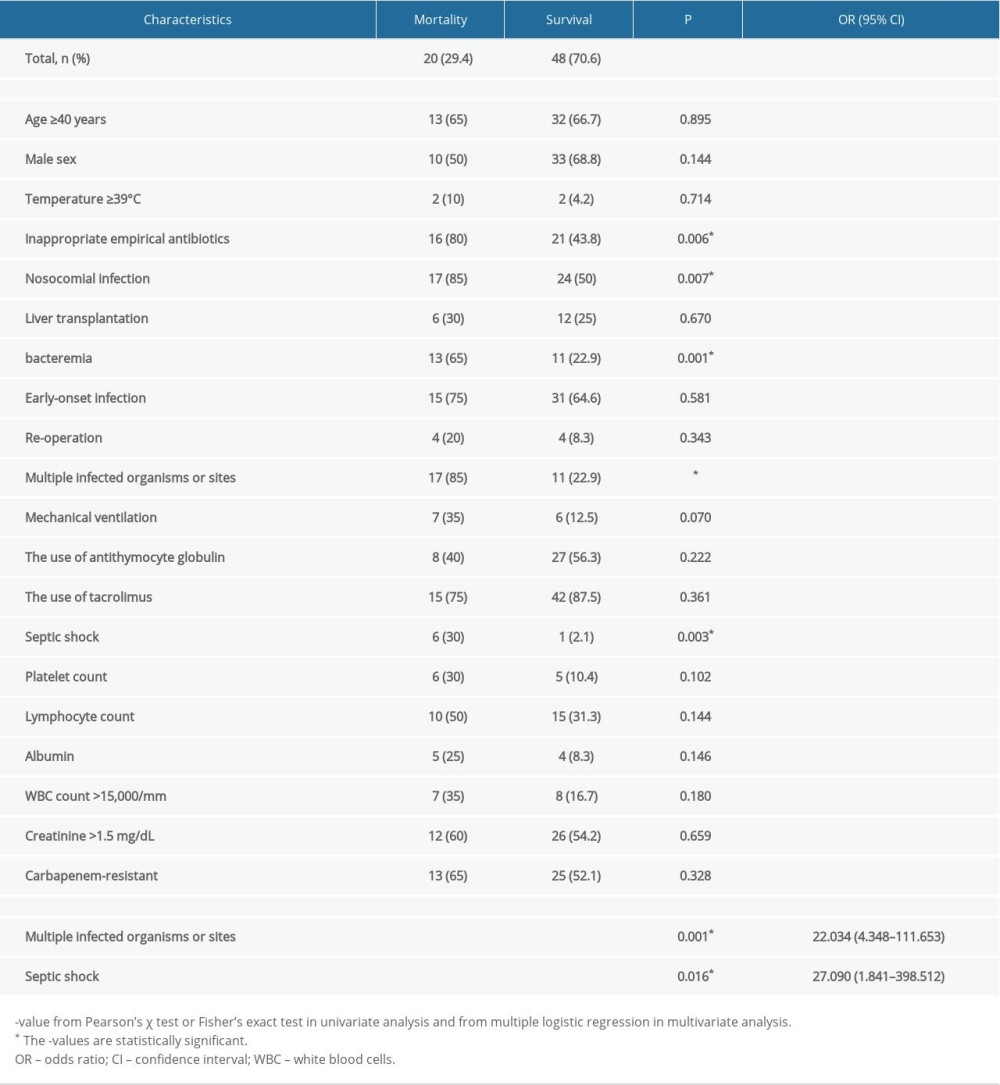

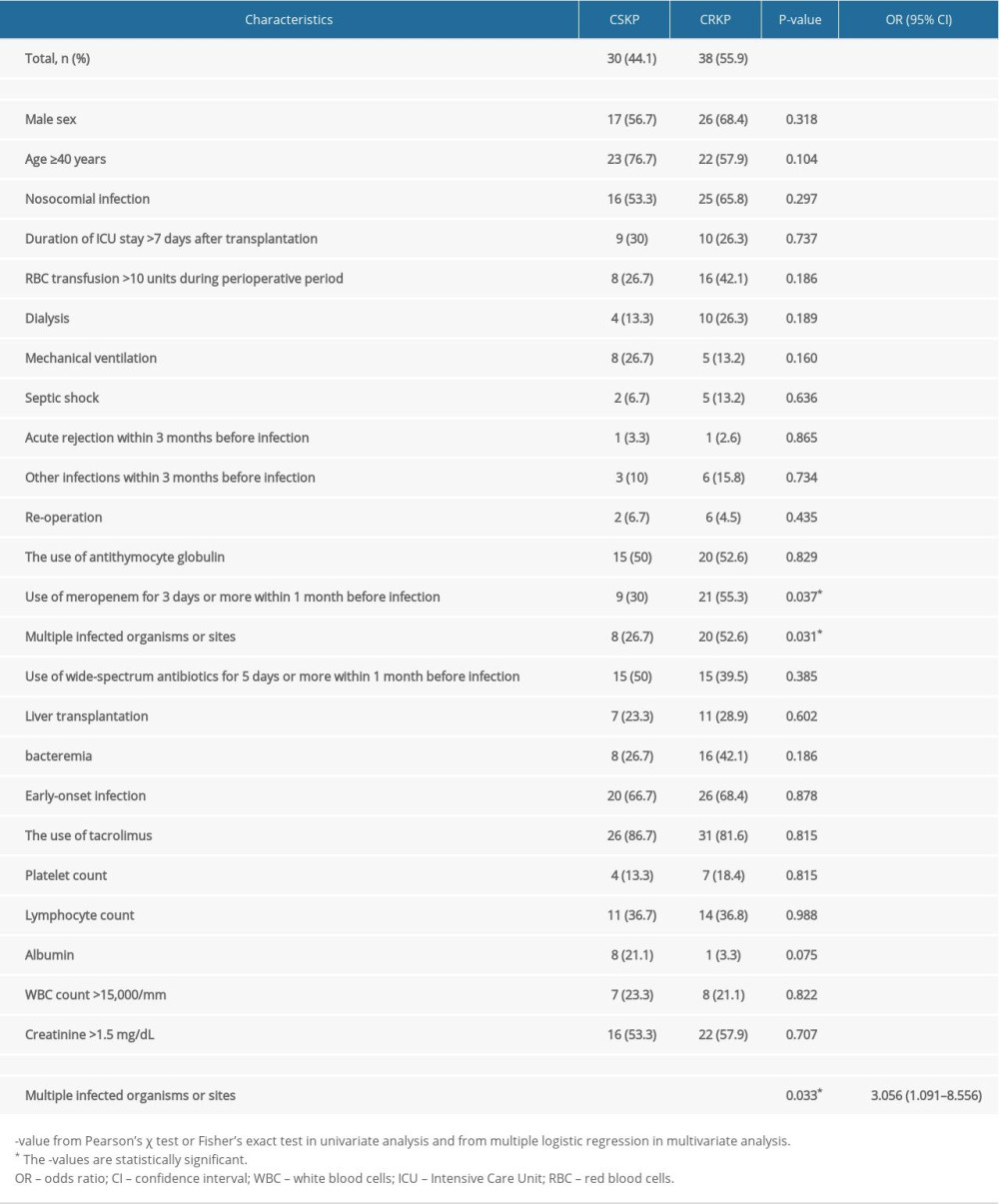

RESULTS: Sixty-eight ASOT recipients (5.4%) experienced 78 episodes of K. pneumoniae infection. Among these, 20 patients (29.4%) died. The independent risk factors associated with mortality were multiple infected organs or sites (odds ratio=22.034, 95% confidence intervals=4.348-111.653, P=0.001) and septic shock (odds ratio=27.090, 95% confidence intervals=1.841-398.512, P=0.016). Risk factors associated with acquisition of CRKP were multiple infected organs or sites (odds ratio=3.056, 95% confidence intervals=1.091–8.556, P=0.033).

CONCLUSIONS: K. pneumoniae infections, especially CRKP, frequently occurred among ASOT recipients, with a high mortality rate. Multiple infected organs or sites and septic shock were predictors of crude mortality caused by K. pneumoniae infections, while CRKP infections were associated with multiple infected organs or sites. Greater efforts are needed towards improved antibiotic administration, early diagnosis and precise treatment, recognition of septic shock, and reduced length of hospitalization.

Keywords: Carbapenems, Drug Resistance, Bacterial, Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections, Mortality, Risk Factors, Transplants, Abdomen, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Klebsiella Infections, Klebsiella pneumoniae, transplant recipients

Background

Solid organ transplantation (SOT) recipients suffer from a high incidence of, and high mortality rate from, life-threatening bacterial infections [1–3]. Recent reports have demonstrated that

SOT recipients have become a high-risk group for infection with drug-resistant bacteria due to frequent exposure to antibiotics, prolonged hospital stays, and renal dysfunction [10]. Carbapenemase-producing

So far, however, there has been little discussion among SOT recipients about the adverse effects of

This study sought to obtain data which will help to address these research gaps. Specifically, our aim was to characterize the risk factors related to CRKP acquisition and 90-day crude mortality among

Material and methods

ETHICS STATEMENT:

The Medical Ethical Committee of Xiangya Third Hospital of Central South University endorsed the study protocol prior to data collection. No recipients or donors were coerced or paid in our study.

STUDY POPULATION:

Our study was a retrospective analysis conducted from December 1, 2012 to July 1, 2019 at the Third Xiangya Hospital, a 1800-bed tertiary-care teaching hospital with a long-term ASOT program (annual average of 180 kidney and 35 liver transplants), located in Changsha, China. All episodes of

DATA COLLECTION AND STUDY DESIGN:

This single-center retrospective study aimed to determine the independent risk factors related to acquisition of CRKP and crude mortality among

The clinical and demographic characteristics included: sex, age, hallmarks of infection (white blood cell count and temperature), date and site of infection, re-operation, induction therapy, CRKP pathogen, nosocomial origin of infection, mechanical ventilation, septic shock, average duration of intensive care unit stay after transplantation, blood transfusion during the perioperative period, type of transplantation, empirical antimicrobial therapy, acute rejection within 3 months before

DEFINITIONS:

Throughout this paper, the onset of K. pneumoniae infection refers to the collection date of the first positive culture with clinical evidence of infection. According to the criteria of the centers for disease control, a patient with a positive culture from blood, sputum, urine, deep wound, skin, or abdominal cavity can be defined as infected [13]. Appropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy was indicated if administration of antibiotics in vitro resulted in susceptible K. pneumoniae within 48 h after having cultured the specimens [16]. Nosocomial infection was considered as having occurred in recipients who had been hospitalized for at least 48 hours, and early-onset infection was defined as developing within the first 2 months after ASOT [17]. CRKP was diagnosed upon a finding of non-susceptibility to at least one antimicrobial agent in the carbapenem category, which included imipenem and meropenem, in accordance with the criteria of the centers for disease control [18]. Septic shock was diagnosed in recipients with K. pneumoniae infection who required vasopressor therapy to maintain mean blood pressure of at least 65 mm Hg and who had a serum lactate level greater than 2 mmol/L after adequate fluid resuscitation [19].

MICROBIOLOGY:

For blood culture, each blood sample was aseptically injected into each of a set of aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles before processing by the BACTEC 9120 blood culture system (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD, USA) in the microbiology laboratory. For other cultures, specimens were obtained for routine bacterial culture. Bacterial species identification was performed using the Vitek-2 system (bioMérieux, Marcyl’Etoile, France).The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was measured by agar dilution, and susceptibility was determined by the Kerby-Bauer disk diffusion method [20]. A strain was considered carbapenem-susceptible when the MIC of meropenem or imipenem was ≤1 mg/L [21]. Intermediate susceptibility to the antibiotics was considered as resistance.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Data are listed as mean (±SD) and median (1st–3rd quartile) for continuous variables with normal and skewed distributions, respectively. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test or Fisher exact test. Univariate analysis was applied to inspect the association between demographic/clinical variables and acquisition of CRKP infections and crude mortality caused by

Results

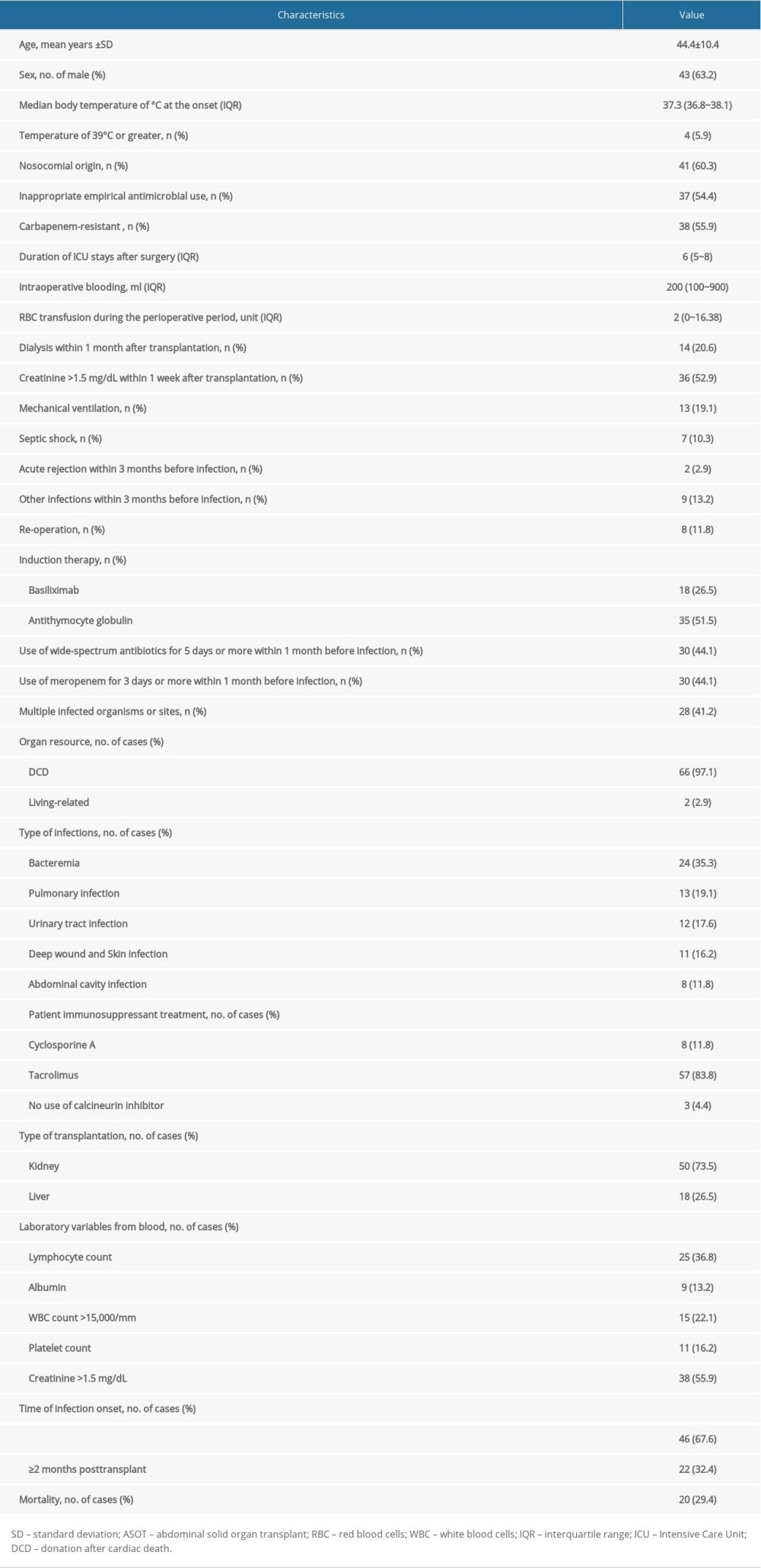

A total of 1249 ASOT recipients, including 1039 kidney and 210 liver recipients, at the Third Xiangya Hospital, were eventually enrolled in this 7-year cohort study. Sixty-eight ASOT recipients with a mean age of 44.4, with 2 and 66 grafts from living related donors and cardiac death donors, respectively, experienced 78 episodes of

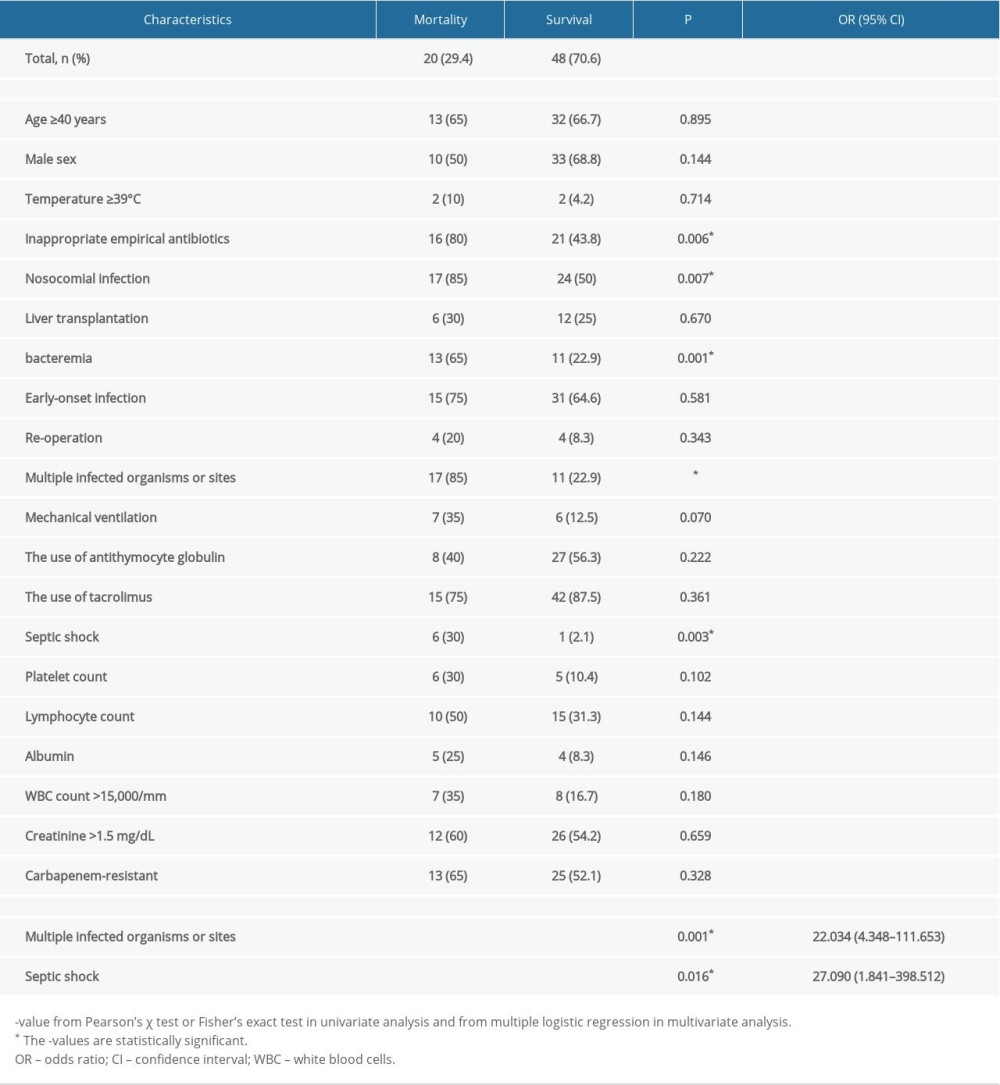

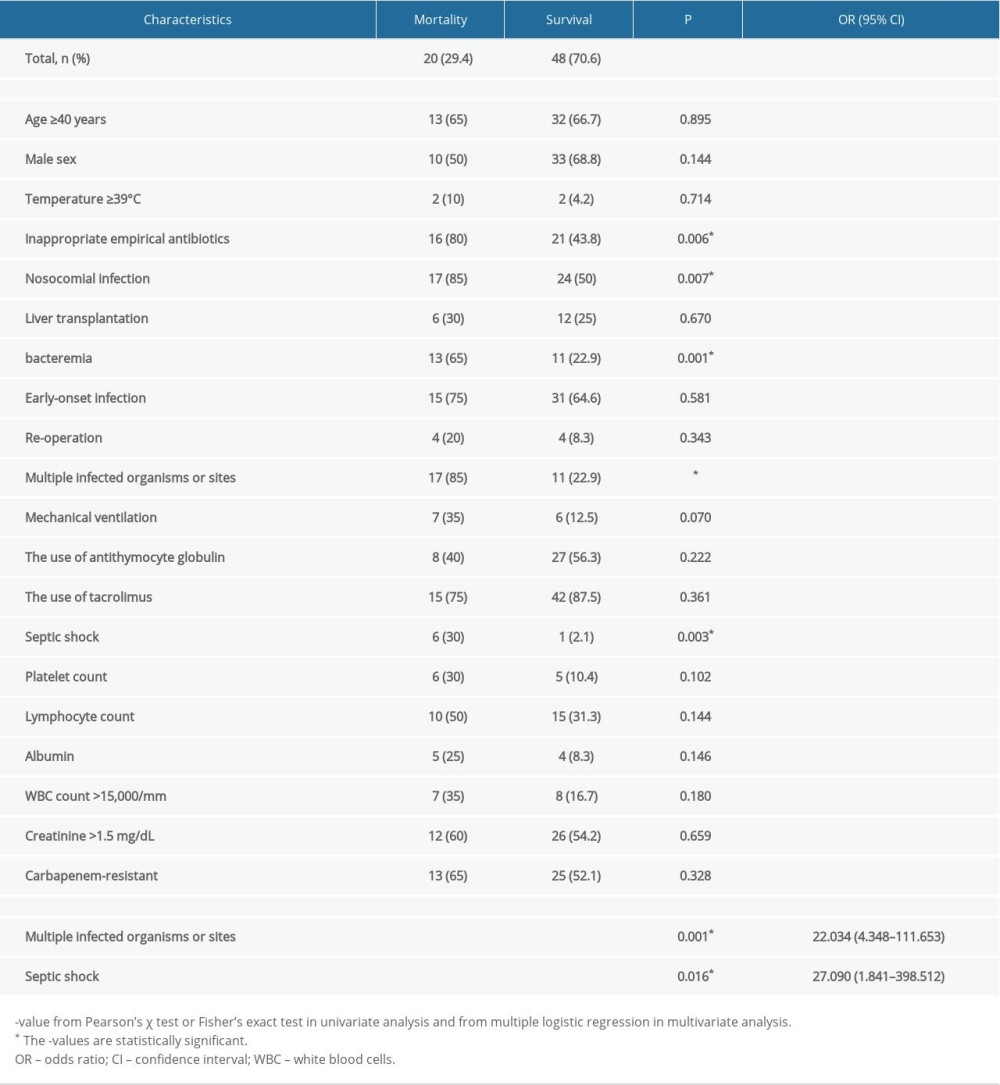

Table 2 shows that in the univariate analysis, mechanical ventilation was needed more frequently in the mortality group, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (

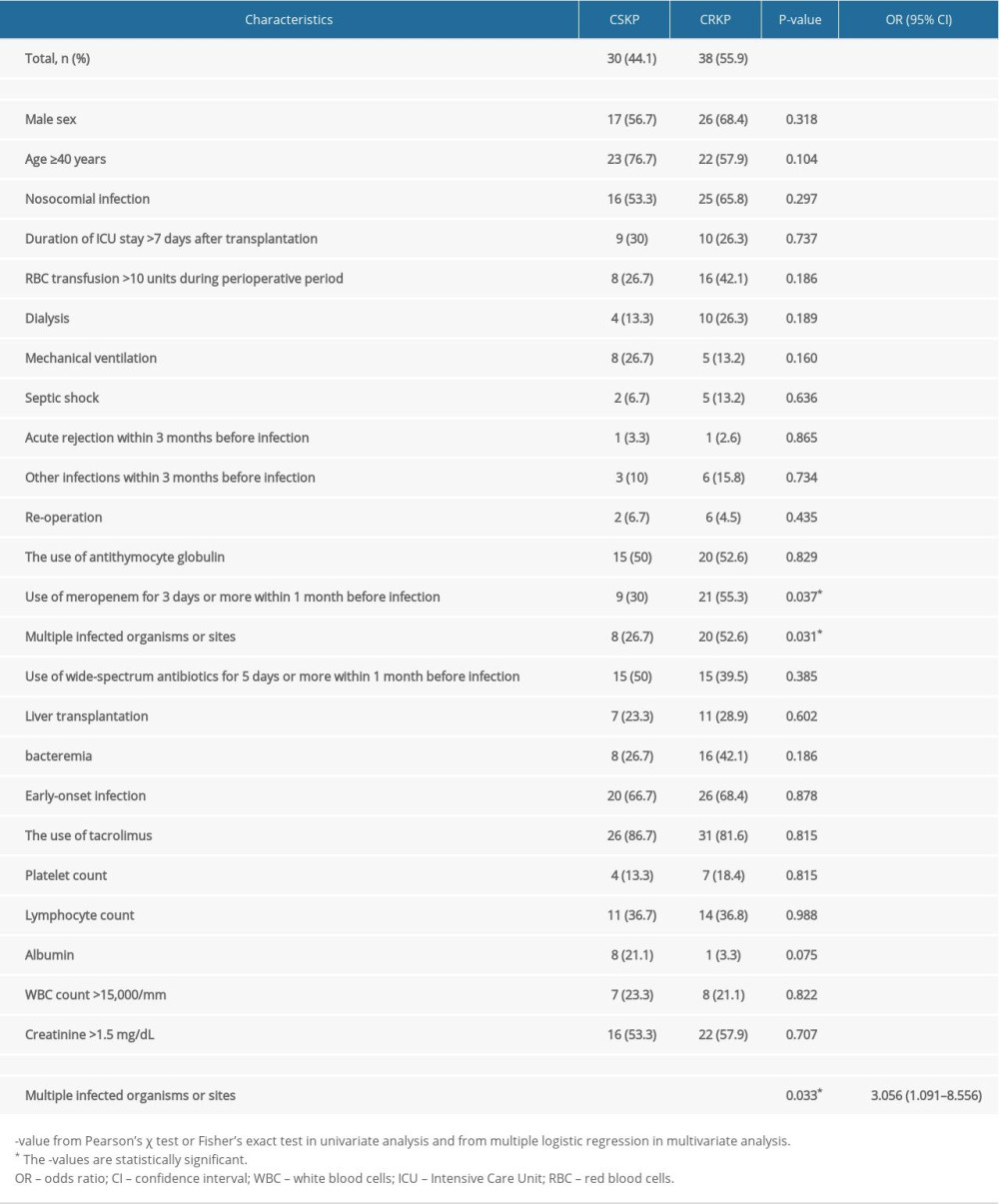

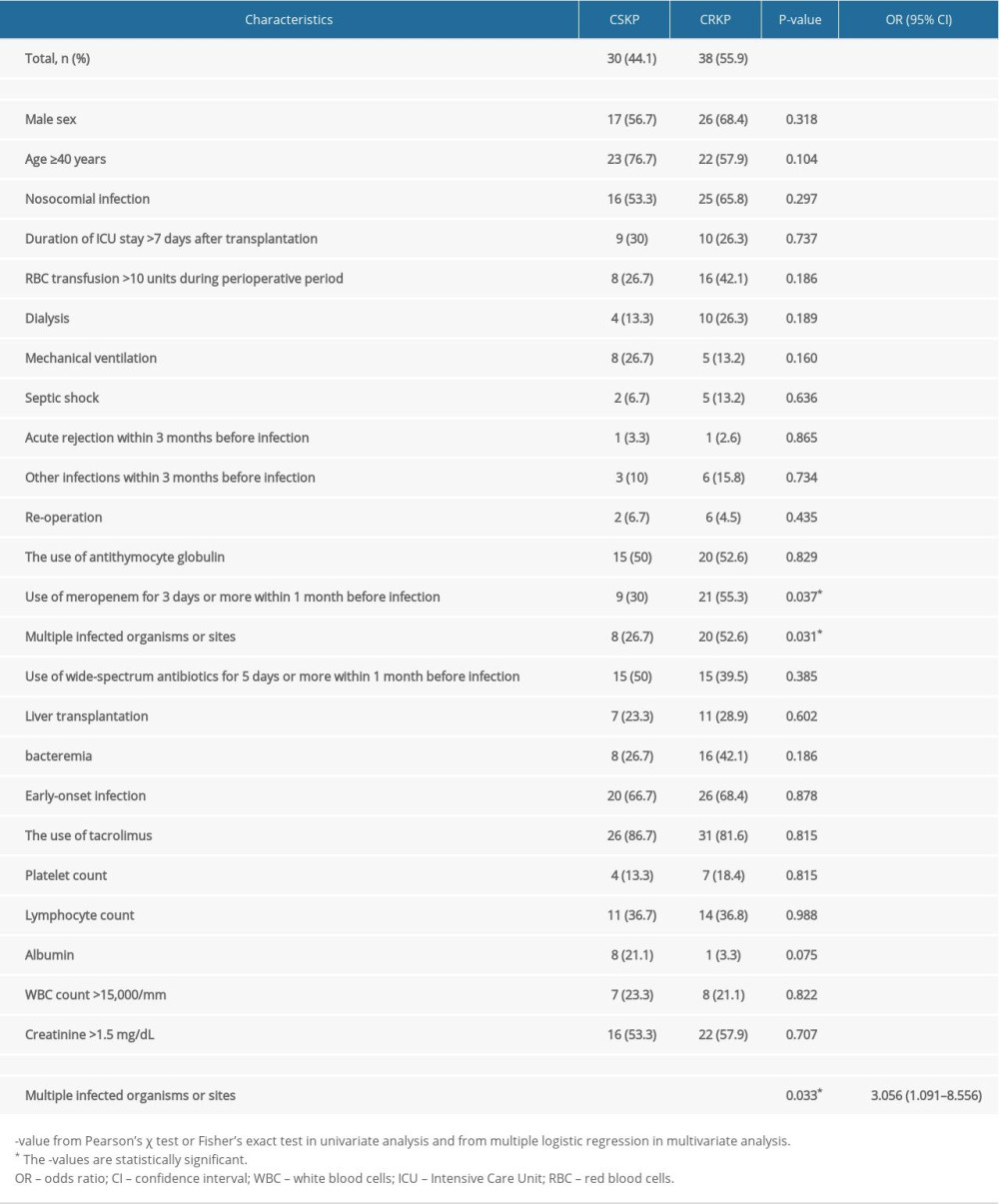

Compared with CSKP infections, the factors associated with CRKP infections in univariate analysis were multiple infected organs or sites (

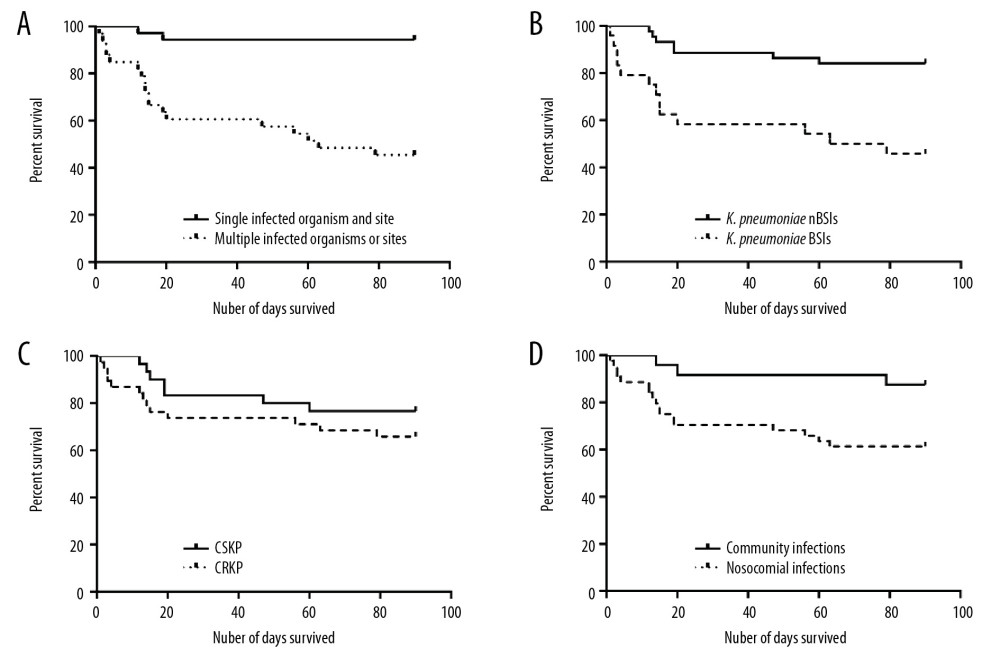

Figure 1 shows the survival time of patients with certain risk factors. Compared with the single infected organ or site group, the mortality was significantly higher in the multiple infected organs or sites group (

Discussion

Infection is a life-threatening complication among SOT recipients.

We observed that

The main revelation of our study was that multiple infected organs or sites were strongly associated with the occurrence of CRKP infections, as well as crude mortality due to

We also revealed that the most common positive cultures of

Nosocomial infection is a great threat among ASOT recipients. In previous studies, Shendi et al. and Lee et al. found that high resistance to antibacterial agents among ASOT recipients was associated with a high rate of nosocomial origins [31,32]. In accordance with our previous study based on ASOT recipients with drug-resistant gram-negative infections, we observed that in the present cohort, based on survival analysis, nosocomial infection induced a significant increase in mortality [24]. Notably, several empirical antibiotics may be prescribed to treat the nosocomial infection, leading to severe drug resistance which could make the choice of antibiotics and the subsequent anti-infective treatments more difficult.

CRKP was widespread in patients in the current study, in line with previous studies revealing that CRKP has spread rapidly and emerged as a great threat to ASOT patients in the last decade [33,34]. ASOT

Previous antibiotic exposure might prevent some infections; however, it has induced an increasing number of CRKP infections among ASOT recipients [7]. We found that the prescription of meropenem for at least 3 days within 1 month prior to

Appropriate antibiotic therapy, administered at the initial stage of infection, influences the outcome of patients with severe bacterial infections. Empiric therapy must not merely be activated as if

Mechanical ventilation, a vital medical treatment for assisted spontaneous breathing, is a cruel source of hospital-acquired pneumonia and a surrogate marker of clinical severity. In our present study, the application of mechanical ventilation was more frequent in the mortality group than in the survival group; however, it was not a predictor of mortality (

Contrary to previous studies that found that CRKP infections frequently occurred in the early period after ASOT, early-onset infection was not found to be a significant risk factor for CRKP infections in our study [21,32]. The value of enhancing prevention within the first two months after transplantation is not clear.

Several limitations need to be indicated in our study. Firstly, our study is limited by its retrospective monocentric study design, the nature of which includes the potential for incorrect written records, deficient data, or selection biases. Prospective studies, adopted to fill this gap, are required to verify our findings. These should be designed to address the role of surveillance of CRKP and management of both CRKP-colonized ASOT donors and their recipients, especially in the current era of donor deficiencies. Secondly, the study should collect more clinical records from different time points in the course of antibiotic therapy, so that the transformation to drug resistant strains of pathogens during ongoing treatment may be understood. Thirdly, the high OR scores have a potential negative predictive value due to the limited sample size of our study. Multicenter, even nationwide, research studies are needed to minimize this bias. Finally, there were also some variables we did not collect, such as Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, the production of carbapenemase, donor transmission of infection, and so on, which may be risk factors associated with

Conclusions

This is the first study to specifically focus on the determination of risk factors related to mortality of

Tables

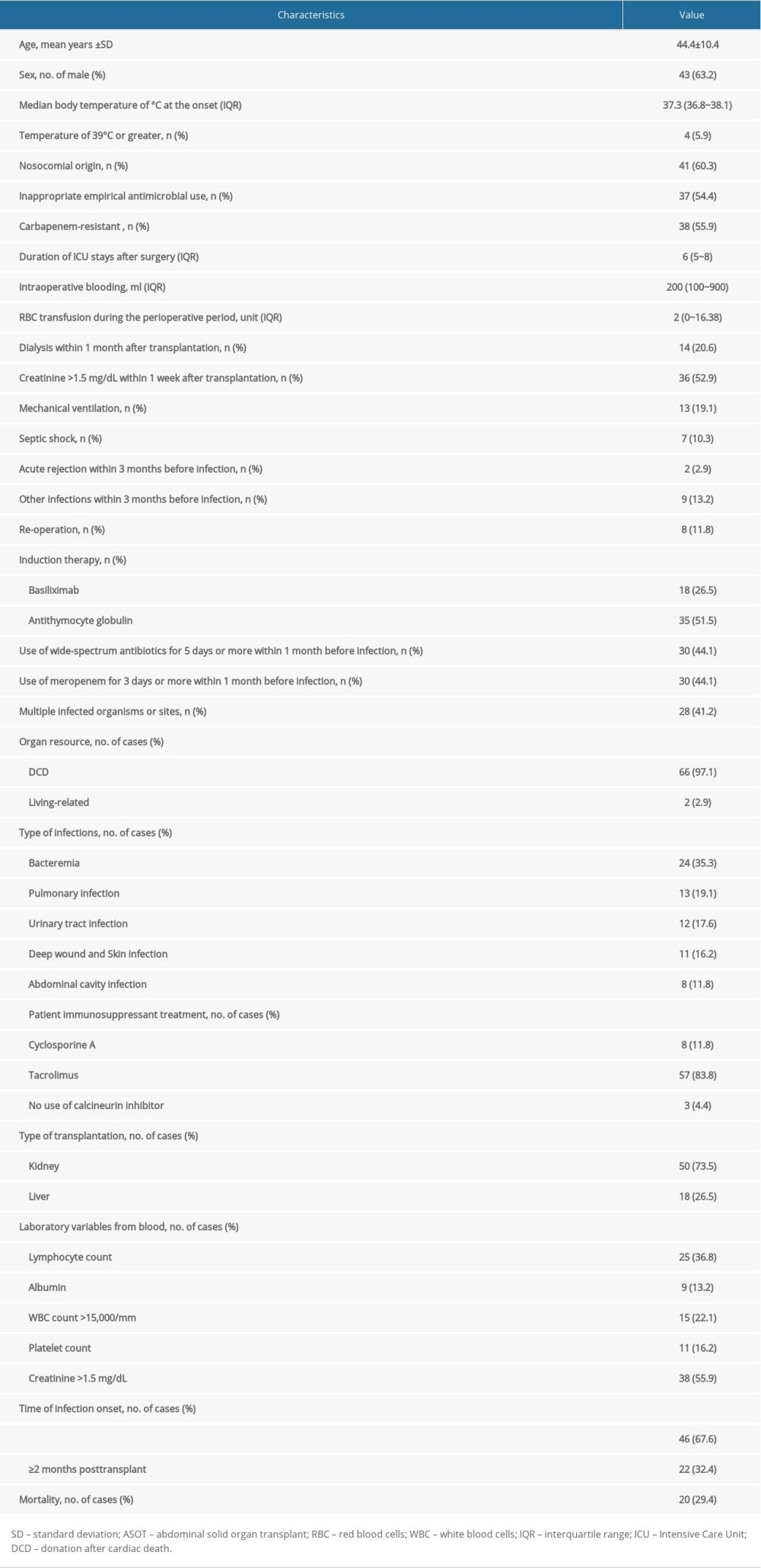

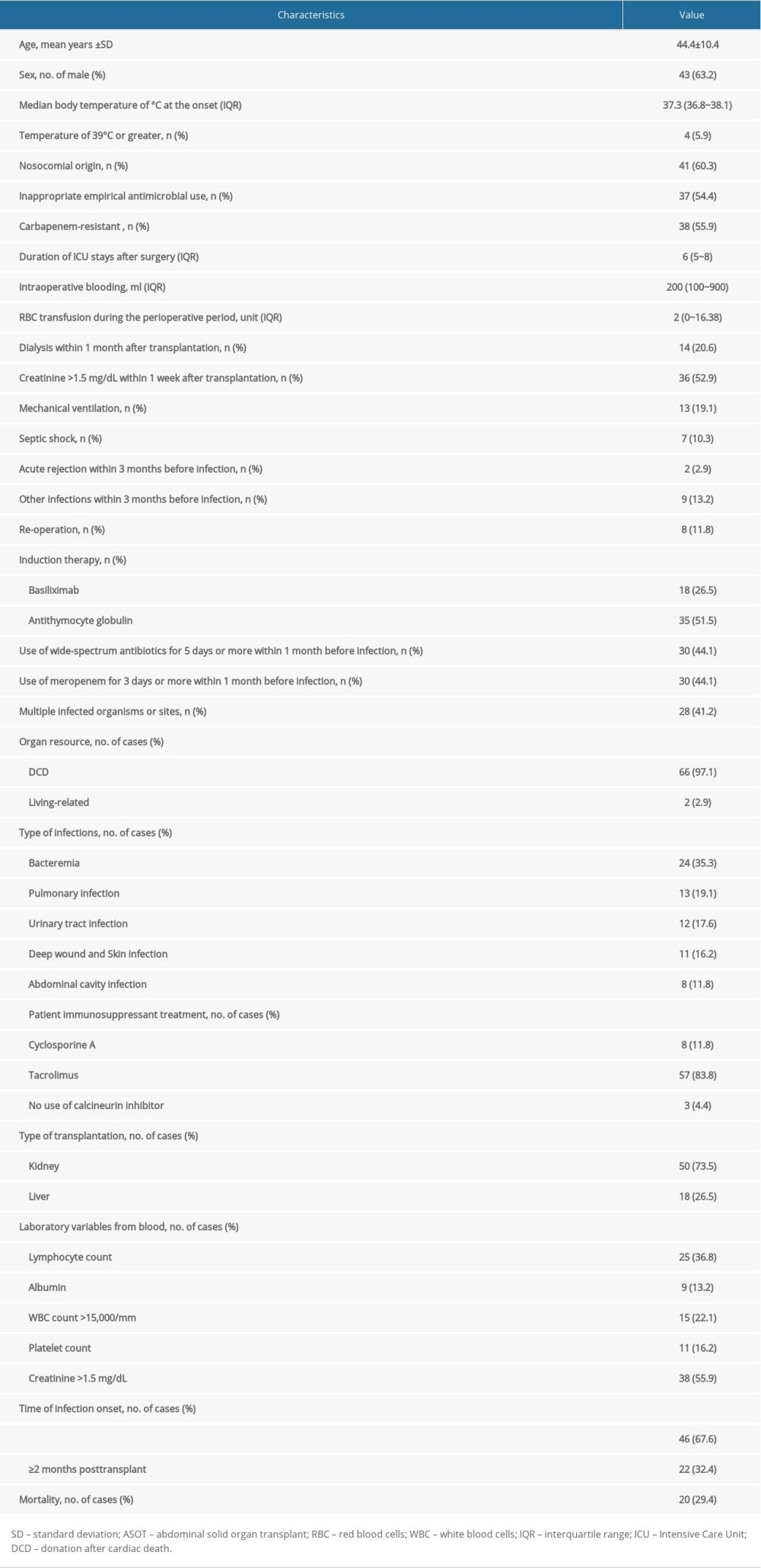

Table 1. Clinical characteristic and demographic, laboratory of 68 K. pneumoniae infections recipients. Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors related to crude mortality in K. pneumoniae infection recipients.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors related to crude mortality in K. pneumoniae infection recipients. Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with the occurrence of CRKP among K. pneumoniae infection recipients.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with the occurrence of CRKP among K. pneumoniae infection recipients.

References

1. Fishman JA, Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients: N Engl J Med, 2007; 357; 2601-14

2. Snyder JJ, Israni AK, Peng Y, Rates of first infection following kidney transplant in the United States: Kidney Int, 2009; 75; 317-26

3. Kusne S, Dummer JS, Singh N, Infections after liver transplantation. An analysis of 101 consecutive cases: Medicine (Baltimore), 1988; 67; 132-43

4. Tzouvelekis LS, Markogiannakis A, Psichogiou M: Clin Microbiol Rev, 2012; 25; 682-707

5. Liang Y, Yin X, Zeng L, Chen S: BMC Infect Dis, 2017; 17; 363

6. Clancy CJ, Chen L, Shields RK: Am J Transplant, 2013; 13; 2619-33

7. Kalpoe JS, Sonnenberg E, Factor SH: Liver Transpl, 2012; 18; 468-74

8. Falagas ME, Lourida P, Poulikakos P, Antibiotic treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Systematic evaluation of the available evidence: Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2014; 58; 654-63

9. Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T: Lancet Infect Dis, 2009; 9; 228-36

10. Moreno CA, Ruiz CINosocomial infection in patients receiving a solid organ transplant or haematopoietic stem cell transplant: Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin, 2014; 32; 386-95 [in Spanish]

11. Linares L, Cervera C, Hoyo I: Transplant Proc, 2010; 42; 2941-43

12. Bergamasco MD, Barroso BM, de Oliveira GD: Transpl Infect Dis, 2012; 14; 198-205

13. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA, CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting: Am J Infect Control, 2008; 36; 309-32

14. Lubbert C, Becker-Rux D, Rodloff AC: Infection, 2014; 42; 309-16

15. Taglietti F, Di Bella S, Galati V: Transpl Infect Dis, 2013; 15; E164-65

16. Lee SO, Kang SH, Abdel-Massih RC, Spectrum of early-onset and late-onset bacteremias after liver transplantation: Implications for management: Liver Transpl, 2011; 17; 733-41

17. Wan QQ, Ye QF, Yuan H, Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in solid organ transplant recipients with bacteremias: Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2015; 34; 431-37

18. Kollef MH, Micek ST, Strategies to prevent antimicrobial resistance in the intensive care unit: Crit Care Med, 2005; 33; 1845-53

19. Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3): JAMA, 2016; 315; 775-87

20. Moreno A, Cervera C, Gavalda J, Bloodstream infections among transplant recipients: Results of a nationwide surveillance in Spain: Am J Transplant, 2007; 7; 2579-86

21. Pereira MR, Scully BF, Pouch SM: Liver Transpl, 2015; 21; 1511-19

22. Pouch SM, Kubin CJ, Satlin MJ: Iranspl Infect Dis, 2015; 17; 800-9

23. Cervera C, van Delden C, Gavalda J, Multidrug-resistant bacteria in solid organ transplant recipients: Clin Microbiol Infect, 2014; 20(Suppl 7); 49-73

24. Qiao B, Wu J, Wan Q, Factors influencing mortality in abdominal solid organ transplant recipients with multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteremia: BMC Infect Dis, 2017; 17; 171

25. Kwak YG, Choi SH, Choo EJ: Microb Drug Resist, 2005; 11; 165-69

26. Fishman JA, Infection in organ transplantation: Am J Transplant, 2017; 17; 856-79

27. Potter RF, D’Souza AW, Dantas G, The rapid spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Drug Resist Updat, 2016; 29; 30-46

28. Shao M, Wan Q, Xie W, Ye Q, Bloodstream infections among solid organ transplant recipients: Epidemiology, microbiology, associated risk factors for morbility and mortality: Transplant Rev (Orlando), 2014; 28; 176-81

29. Candel FJ, Grima E, Matesanz M, Bacteremia and septic shock after solid-organ transplantation: Transplant Proc, 2005; 37; 4097-99

30. Song SH, Li XX, Wan QQ, Ye QF, Risk factors for mortality in liver transplant recipients with ESKAPE infection: Transplant Proc, 2014; 46; 3560-63

31. Shendi AM, Wallis G, Painter H, Epidemiology and impact of bloodstream infections among kidney transplant recipients: A retrospective single-center experience: Transpl Infect Dis, 2018; 20(1)

32. Lee KH, Han SH, Yong D, Acquisition of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae in solid organ transplantation recipients: Transplant Proc, 2018; 50; 3748-55

33. Beceiro A, Tomas M, Bou G, Antimicrobial resistance and virulence: A successful or deleterious association in the bacterial world?: Clin Microbiol Rev, 2013; 26; 185-230

34. Lanini S, Costa AN, Puro V, Incidence of carbapenem-resistant gram negatives in Italian transplant recipients: A nationwide surveillance study: PLoS One, 2015; 10; e123706

35. Girometti N, Lewis RE, Giannella M: Medicine (Baltimore), 2014; 93; 298-309

36. Bafi AT, Tomotani DY, de Freitas FG, Sepsis in solid-organ transplant patients: Shock, 2017; 47; 12-6

37. Kalil AC, Sandkovsky U, Florescu DF, Severe infections in critically ill solid organ transplant recipients: Clin Microbiol Infect, 2018; 24; 1257-63

38. Bias TE, Malat GE, Lee DH: Infect Dis (Lond), 2018; 50; 67-70

39. Lin JN, Chen YH, Chang LL, Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteremias in the emergency department: Intern Emerg Med, 2011; 6; 547-55

40. Kohira N, West J, Ito A: Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2016; 60; 729-34

41. Garonzik SM, Li J, Thamlikitkul V, Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients: Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011; 55; 3284-94

Tables

Table 1. Clinical characteristic and demographic, laboratory of 68 K. pneumoniae infections recipients.

Table 1. Clinical characteristic and demographic, laboratory of 68 K. pneumoniae infections recipients. Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors related to crude mortality in K. pneumoniae infection recipients.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors related to crude mortality in K. pneumoniae infection recipients. Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with the occurrence of CRKP among K. pneumoniae infection recipients.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with the occurrence of CRKP among K. pneumoniae infection recipients. Table 1. Clinical characteristic and demographic, laboratory of 68 K. pneumoniae infections recipients.

Table 1. Clinical characteristic and demographic, laboratory of 68 K. pneumoniae infections recipients. Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors related to crude mortality in K. pneumoniae infection recipients.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors related to crude mortality in K. pneumoniae infection recipients. Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with the occurrence of CRKP among K. pneumoniae infection recipients.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with the occurrence of CRKP among K. pneumoniae infection recipients. In Press

15 Apr 2024 : Laboratory Research

The Role of Copper-Induced M2 Macrophage Polarization in Protecting Cartilage Matrix in OsteoarthritisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943738

07 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 179 Male Third- and Fourt...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943468

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952