22 August 2023: Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Laparoscopic Pancreatoduodenectomy in Elderly Patients: Safety, Efficacy, and Cost Evaluation

Chengfang Wang1ABCDEF, Zhijiang Wang1ABDF, Weilin Wang1ADFG*DOI: 10.12659/MSM.940176

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940176

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The use of laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy in elderly patients has sparked debate due to concerns about its safety. This study evaluates its safety and efficacy for elderly patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed data from 250 patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy between January 2015 and April 2022. Group A consisted of 100 non-elderly patients (under 70) who had laparoscopic procedures; Group B had 60 elderly patients (70 and above) with laparoscopic surgeries; and Group C included 90 elderly patients with open surgeries. Clinical outcomes were then compared across the groups.

RESULTS: Elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy experienced a higher conversion rate (35% vs 19%), increased ICU admissions post-operation (45% vs 23%), a prolonged ICU stay, greater hospital expenses (¥118,782.48 vs ¥106,698.38), and a lower post-operative adjuvant therapy rate (31.91% vs 69.23%). However, they had fewer B-C pancreatic fistulas (5% vs 24%). Compared to open surgery in elderly patients, laparoscopic procedure showed benefits such as reduced blood loss (median of 200 ml) and fewer wound infections (3.33% vs 17.78%). On the downside, laparoscopy had a longer operation time (462.5 minutes vs 315 minutes), took longer before patients could resume oral intake (median of 5.5 days vs 5 days), and incurred higher hospitalization costs (¥118,782.48 vs ¥111,541.60).

CONCLUSIONS: While laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy in elderly patients may not match the outcomes seen in younger patients, it doesn’t possess marked drawbacks when compared to open surgery. It is a safe and viable option for the elderly.

Keywords: Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Frail Elderly, Postoperative Complications, Mortality, Laparoscopy, Humans, Middle Aged, Retrospective Studies, Combined Modality Therapy, Hospitalization

Background

In 1935, American doctor Whipple took the lead in completing the first pancreatoduodenectomy operation, also called the Whipple operation [1]. Since then, open pancreatoduodenectomy (OPD) has been adopted widely worldwide. After over 80 years of development, OPD is the standard operation for treating lower bile duct tumors, periampullary tumors, duodenal papilla tumors, and pancreatic head tumors, and its perioperative mortality rate has decreased from 45% to 0.8% [2]. As part of the proposal and development of minimally invasive surgery, Gagner finished the first laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy in the world in 1994 [3]; after that, laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy (LPD) was gradually adopted worldwide. Due to the prolonged operative time and high morbidity and mortality rates, its development has been very slow, and its application is limited. With modernization and improvement of surgical equipment and surgical technology, LPD has become more widely used.

Nevertheless, the debate and questions about the safety and feasibility of LPD continued and reached a peak after a multicenter randomized controlled study was stopped early because of concern about the safety of LPD [4]. Although LPD has become more accepted, LPD replacing OPD and becoming the standard operation still have a long way to go. Elderly people tend to be fragile, have more cardiopulmonary comorbidities, and have worse physical status, limiting their ability to tolerate surgical trauma, and advanced age is a risk factor for postoperative complications and mortality [5–7]. LPD surgery entails long-term pneumoperitoneum and anesthesia, massive surgical trauma, and a high risk of postoperative morbidities, and it is a big challenge for elderly patients. Furthermore, CO2 pneumoperitoneum was found to be associated with adverse effects, such as hypercapnia, unstable hemodynamics, decreased renal function, and peritoneal oxidative stress [8,9], but it is unclear whether these have a significant impact on elderly patients. In clinical practice, when the elderly are referred for PD or LPD, their relatives worry that the elderly patients cannot tolerate surgery and will have severe complications, great pain, long recovery, and poor quality of life. Furthermore, they want to know whether LPD has some advantages over OPD. Unfortunately, studies have found that LPD in the elderly has significant disadvantages compared with the non-elderly, and a meta-analysis in 2022 revealed that the benefits of LPD in elderly patients were limited [10–12]. Therefore, they often refuse surgery. The present study sought to resolve these problems. LPD is controversial and it is unclear if LPD is safe and suitable for older people. This retrospective study aimed to explore the safety and feasibility of LPD for elderly patients.

Material and Methods

PATIENTS:

This retrospective study collected clinical data of consecutive patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy in the Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, the Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, from January 2015 to April 2022. Two groups of surgeons performed all LPD surgeries. OPD was performed by these 2 and some other groups of surgeons who have not conducted LPD yet, and all patients followed the standard postoperative treatment protocol. Referring to previous literature, we defined elderly as ≥70 years old. Therefore, we divided these patients into 3 groups: non-elderly LPD patients <70 years old were assigned to group A, elderly LPD patients ≥70 years old were assigned to group B, and elderly OPD patients ≥70 years old were assigned to group C.

ETHICAL APPROVAL:

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China. All procedures in this study followed protocols approved by the Ethics Committee (2021-0677). In addition, written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the operation.

INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA:

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients undergoing LPD or OPD surgery for an ampullary tumor, pancreatic head tumor, lower common bile duct tumor, or descending duodenal tumor. (2) The preoperative imaging assessment without distant metastases and portal vein invasion is less than 180°.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with combined resection of other abdominal organs. (2) LPD patients converted to open procedures only after laparoscopic exploration. (3) Pylorus preservation pancreatoduodenectomy patients.

We finally included 250 patients in this research according to the above criteria: 100 patients in group A, 60 in group B, and 90 in group C.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES:

All LPDs were performed in a total laparoscopic procedure. LPD patients were under general anesthesia and in a horizontal, head-up position. Pneumoperitoneum pressure was 12–14 mmHg. Trocar distribution, like the letter “V”, is shown in Figure 1. The resection process was as follows: 1) Kocher dissociation; 2) stomach transaction; 3) dissect the hepatoduodenal ligament, then cholecystectomy was performed and transection of the common bile duct; 4) pancreas transection; 5) jejunum transaction; 6) dissection of the superior mesenteric vein-portal vein system; 7) dissection of the superior mesenteric artery-celiac trunk system and transection of the uncinate process. After resection, a 5–8-cm incision (median upper abdomen or umbilical incision, shown in Figure 1) was made to remove the specimen. The reconstruction period: The anastomotic of the pancreatic intestine, biliary intestine, and gastrointestinal tract were reconstructed. All operations were pancreaticojejunostomy, and no pancreaticogastrostomy was performed. All OPD patients underwent a classical Whipple procedure. Child’s anastomosis procedure and duct-to-mucosa technique were used in reconstruction in all patients.

OBSERVATIONAL INDEX:

Baseline parameters included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), preoperative morbidities (especially for hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases), past abdominal surgery history, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (ASA) score, neoadjuvant therapy, preoperative jaundice (≥21 μmol/L), and preoperative biliary drainage. The pathological data included tumor location, type, size, margin status, and lymph node(s) harvested. Intraoperative data included overall operation time, estimated blood loss (EBL), and operation transfusion. Short-term postoperative outcome parameters included postoperative hospital stay (POHS), intensive care unit (ICU) admission and stay, reoperation rate, 30-day readmission, 90-day mortality, and postoperative morbidities. Postoperative morbidities refer to postoperative infection, bile fistula, postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), delayed gastric emptying (DGE), post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH), Chyle fistula, and so on. Complications were recorded following the Clavien-Dindo classification system [13]. Postoperative infections refer to not only surgical site infections but also other infections. Postoperative infection was defined as postoperative >3 days temperature >38.5°C, white blood cell (WBC) counts >10×109/L >3 days after the operation or after WBC return to normal, or antibiotic used >7 days after surgery, with or without CRP and PCT abnormal. POPF, bile fistula, DGE, chyle fistula, and PPH were defined according to the 2016 International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery definitions [14].

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation or median with the interquartile range depending on the data distribution. We used a

Results

BASELINE AND PATHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS:

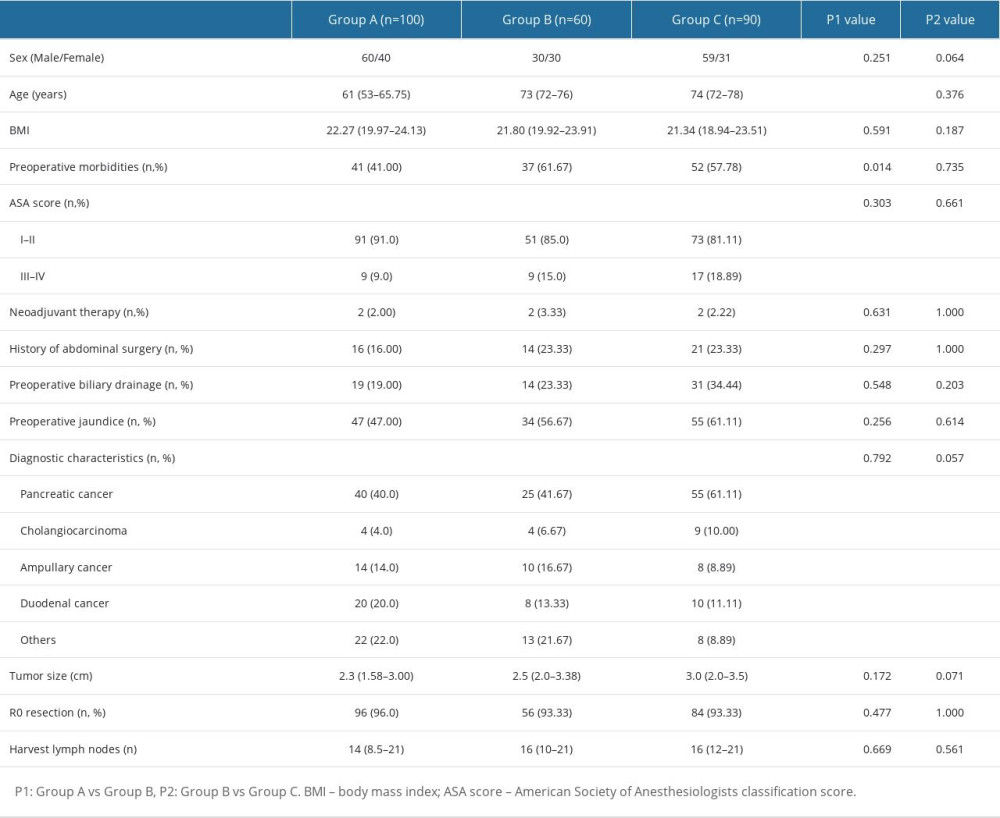

As shown in Table 1, baseline and pathological characteristics were well-balanced in groups. Comparing elderly to non-elderly LPD patients (group A vs group B), age and preoperative morbidities were significantly higher in elderly patients, with a median age of 73 vs 61 years old, and 61.67% vs 41.00%, P<0.001, 0.014. Other parameters were comparable between the 2 groups. Comparing elderly LPD patients to OPD patients, there was a higher proportion of males, the proportion of malignancy tended to be higher, and tumor size tended to be larger in OPD patients, but without statistically significant differences (P=0.064, 0.057, 0.071), and all other parameters were not significantly different between the 2 groups (P>0.05). R0 resection rate and lymph nodes harvested were also comparable between groups.

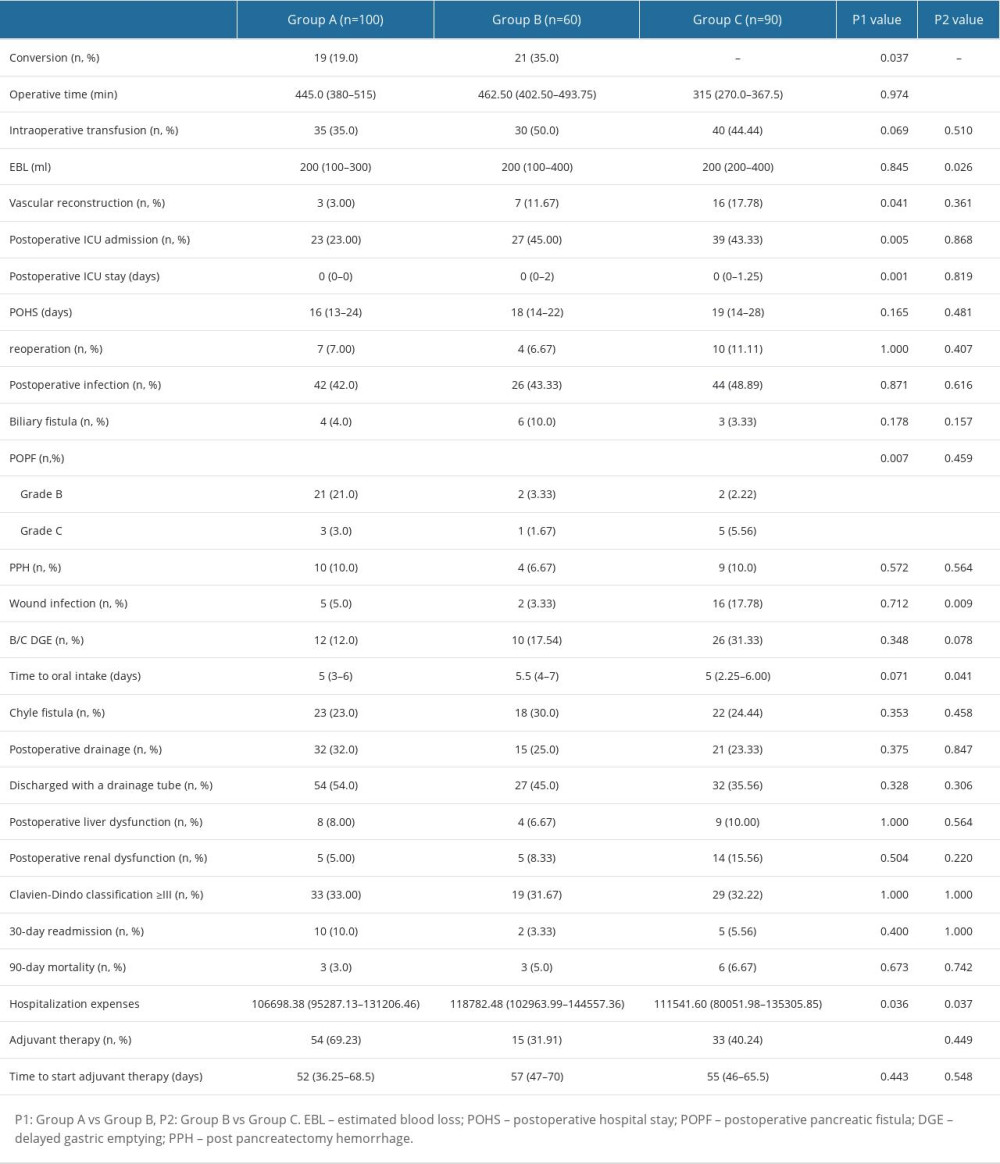

LPD SUBGROUP: ELDERLY VS NON-ELDERLY PATIENTS: The conversion rate was significantly higher in elderly LPD patients (35.0% vs 19.0%, P=0.037). We further analyzed reasons for conversion of surgery. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups; 7 in group A and 12 in group B were due to close or locally invaded mesenteric vessels, 1 patient in each group was unable to tolerate further pneumoperitoneum, and 11 patients in group A and 8 patients in group B had other reasons. More elderly patients than non-elderly patients received vascular reconstruction (11.67% vs 3.00%, P=0.041). Operative time, estimated blood loss, and intraoperative transfusion rate were comparable between groups. Regarding postoperative outcomes, elderly patients needed more and longer ICU stays (45.00% vs 23.00% and median 0 vs 0 days, P=0.005, 0.001). Fewer grade B/C pancreatic fistula patients were found in the elderly group (P=0.007). Elderly patients received less adjuvant therapy (31.91% vs 69.23%, P<0.001) and had higher hospitalization expenses (118 782.48 vs 106 698.38 RMB, P=0.036). Other parameters were not significantly different (P>0.05). Details are shown in Table 2.

ELDERLY SUBGROUP: LPD VS OPD: Operative time was significantly shorter, and estimated blood loss (though the median was the same) was greater in OPD patients (median 315.0 vs 462.5 minutes, 200 vs 200 ml, P<0.001, 0.026). All other intraoperative parameters were comparable. For postoperative parameters, OPD was associated with more wound infection (17.78% vs 3.33%, P=0.009), earlier resumption of oral intake (5 vs 5.5 days, P=0.041), and lower hospitalization expenses (111 541.60 vs 118 782.48 RMB, P=0.037). Other outcomes were comparable between the 2 groups (P>0.05). Details are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

LIMITATIONS:

There are several limitations to our study. First, this was a retrospective study, and selection bias was unavoidable. Secondly, our sample size was relatively small, and our results need to be verified by larger, multicenter studies. Thirdly, we only focused on perioperative and pathological outcomes and lacked long-term survival data. Fourthly, besides surgical technology and safety, quality of life and other aspects also need our attention. Finally, various studies have used different definitions of the elderly, which may have influenced results.

Conclusions

The safety of LPD is satisfactory compared with OPD. In addition, LPD has less estimated intraoperative blood loss and less wound infection. However, it has the disadvantages of longer operative time, longer time to resume oral intake, and higher hospitalization costs. Furthermore, it seems LPD could not wholly offset the influence of age; although less pancreatic fistula occurs in the elderly, we are concerned about a higher conversion rate, more ICU readmissions, lower adjuvant therapy rate, and higher hospitalization costs. In summary, LPD is safe and feasible in elderly patients and could be an alternative to OPD, especially for experienced surgeons.

References

1. Whipple AO, Parsons W, Mullins C, Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: Ann Surg, 1935; 102; 763-79

2. Fernández-del Castillo C, Morales-Oyarvide V, McGrath D, Evolution of the Whipple procedure at the Massachusetts General Hospital: Surgery, 2012; 152(3 Suppl 1); S56-63

3. Gagner M, Pomp A, Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy: Surg Endosc, 1994; 8(5); 408-10

4. Strobel O, Büchler MW, Laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy: Safety concerns and no benefits: Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019; 4(3); 186-87

5. Sukharamwala P, Thoens J, Szuchmacher M, Advanced age is a risk factor for post-operative complications and mortality after a pancreaticoduodenectomy: A meta-analysis and systematic review: HPB (Oxford), 2012; 14(10); 649-57

6. Chen YT, Ma FH, Wang CF, Elderly patients had more severe postoperative complications after pancreatic resection: A retrospective analysis of 727 patients: World J Gastroenterol, 2018; 24(7); 844-51

7. Kim SY, Weinberg L, Christophi C, The outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients aged 80 or older: A systematic review and meta-analysis: HPB (Oxford), 2017; 19; 475-82

8. Bablekos GD, Michaelides SA, Roussou T, Changes in breathing control and mechanics after laparoscopic vs open cholecystectomy: Arch Surg, 2006; 141; 16-22

9. Ülker K, Hüseyinoğlu Ü, Kılıç N, Management of benign ovarian cysts by a novel, gasless, single-incision laparoscopic technique: Keyless abdominal rope-lifting surgery (KARS): Surg Endosc, 2013; 27; 189-98

10. Tee MC, Croome KP, Shubert CR, Laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy does not completely mitigate increased perioperative risks in elderly patients: HPB (Oxford), 2015; 17(10); 909-18

11. Chapman BC, Gajdos C, Hosokawa P, Comparison of laparoscopic to open pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Surg Endosc, 2018; 32(5); 2239-48

12. Yin T, Qin T, Wei K, Comparison of safety and effectiveness between laparoscopic and open pancreatoduodenectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Int J Surg, 2022; 105; 106799

13. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience: Ann Surg, 2009; 250; 187-96

14. Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after: Surgery, 2017; 161(3); 584-91

15. Kaman L, Chakarbathi K, Gupta A, Impact of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery protocol on immediate surgical outcome in elderly patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: Updates Surg, 2019; 71; 653-57

16. Sugimachi K, Iguchi T, Mano Y, The impact of immunonutritional and physical status on surgical outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients: Anticancer Res, 2019; 39; 6347-53

17. Dang C, Wang M, Zhu F, Comparison of laparoscopic and open pancreaticoduodenectomy for the treatment of nonpancreatic periampullary adenocarcinomas: A propensity score matching analysis: Am J Surg, 2021; 222(2); 377-82

18. Liang Y, Zhao L, Jiang C, Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients: Surg Endosc, 2020; 34(5); 2028-34

19. Mazzola M, Giani A, Crippa J, Totally laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: A propensity score matching analysis of short-term outcomes: Eur J Surg Oncol, 2021; 47(3 Pt B); 674-80

20. Shin H, Song KB, Kim YI, Propensity score-matching analysis comparing laparoscopic and open pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients: Sci Rep, 2019; 9; 12961

21. Wang M, Li D, Chen R, Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours: A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial: Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021; 6(6); 438-47

22. Ke J, Liu Y, Liu F, Application of laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy in elderly patients: J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A, 2020; 30(7); 797-802

23. Zhang W, Huang Z, Zhang J, Effect of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly people: A meta-analysis: Pancreas, 2021; 50(8); 1154-62

24. Sharpe SM, Talamonti MS, Wang CE, Early national experience with laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma: a comparison of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy and open pancreaticoduodenectomy from the National Cancer Data Base: J Am Coll Surg, 2015; 221(1); 175-84

25. Meng L, Xia Q, Cai Y, Impact of patient age on morbidity and survival following laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech, 2019; 29; 378-82

26. Cai H, Wang Y, Cai Y, The effect of age on short- and long-term outcomes in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoing laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: Pancreas, 2020; 49; 1063-68

27. Torphy RJ, Friedman C, Halpern A, Comparing short-term and oncologic outcomes of minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy across low and high volume centers: Ann Surg, 2019; 270(6); 1147-55

28. Tan Y, Tang T, Zhang Y, Laparoscopic vs. open pancreaticoduodenectomy: A comparative study in elderly people: Updates Surg, 2020; 72(3); 701-7

29. Marjanovic G, Kuvendziska J, Holzner PA, prospective clinical study evaluating the development of bowel wall edema during laparoscopic and open visceral surgery: J Gastrointest Surg, 2014; 18(12); 2149-54

30. Zhu J, Wang G, Du P, Minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis: World J Surg, 2021; 45(4); 1186-201

31. Choi M, Hwang HK, Rho SY, Comparing laparoscopic and open pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with pancreatic head cancer: Oncologic outcomes and inflammatory scores: J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, 2020; 27(3); 124-31

32. van Hilst J, Brinkman DJ, de Rooij T, The inflammatory response after laparoscopic and open pancreatoduodenectomy and the association with complications in a multicenter randomized controlled trial: HPB (Oxford), 2019; 21(11); 1453-61

33. Strobel O, Brangs S, Hinz U, Incidence, risk factors and clinical implications of chyle leak after pancreaticsurgery: Br J Surg, 2017; 104(1); 108-17

34. Yuan F, Essaji Y, Belley-Cote EP, Postoperative complications in elderly patients following pancreaticoduodenectomy lead to increased postoperative mortality and costs. A retrospective cohort study: Int J Surg, 2018; 60; 204-9

In Press

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952