16 August 2023: Clinical Research

Long-Term Impairment in Activities of Daily Living Following COVID-19 in Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities

Łukasz GoździewiczDOI: 10.12659/MSM.941197

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e941197

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Long-term care facilities were severely impacted during the COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) pandemic. Residents surviving the disease might continue to suffer from the post-COVID syndrome, similar to community-dwelling persons. This study aimed to characterize the longitudinal evolution of activities of daily living in COVID-19 survivors from long-term institutional care.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: This was a retrospective study with prospective follow-up of consecutive COVID-19 survivors living in long-term care facilities. The Barthel Index was used to assess changes in functional independence before the disease, right after recovery, and 3 months later.

RESULTS: The study enrolled 201 residents of long-term care facilities, median age 79 years old, who survived 3 months after recovery from COVID-19. The disease caused hospitalization in 47% of cases. Early after COVID-19, deterioration in activities of daily living was higher in older, hospitalized patients with cardiovascular comorbidity. However, in the long-term follow-up, these factors did not predict functioning. Independence was severely affected in hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients. This had implications for post-COVID care and rehabilitation since these interventions were mainly offered after hospitalization.

CONCLUSIONS: The findings support that residents of long-term care facilities who had COVID-19, even with a mild clinical course, may have persistent impairment in function and ability to perform activities of daily living that require support and rehabilitation.

Keywords: COVID-19, Activities of Daily Living, Hospitalization, Institutionalization, Humans, Aged, Long-Term Care, COVID-19, Prospective Studies, Retrospective Studies

Background

Institutionalized elderly care in many countries was seriously impacted during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Residents of health and social care support facilities are the most vulnerable to COVID-19 due to their fragility, multimorbidity, and the closed environment promoting disease transmission [1,2]. Common psychiatric and neurologic morbidities of institutionalized care residents limit the possibility of social distancing and other infection prevention policies [3,4] and is associated with a higher burden of the disease [5].

Before the pandemic, about 6.5% of older adults in the United States and 3.6% in the European Union lived in institutional care, requiring support in activities of daily living (ADL) and/or medical care [6,7]. These numbers will increase in the future; eg, about 70% of Americans turning age 65 years old today will need long-term care services [8]. The inability to accomplish essential ADL decreases the quality of life and causes safety concerns for older adults. ADL measures reflect an individual’s level of functioning and qualification for assistance, including long-term care in an institutional setting. Poor ability to perform ADL have been shown to predict increased severity and mortality of COVID-19 in different populations [9]. In turn, the consequences of the pandemic have been particularly devastating for senior populations in long-term care [10–13]. One of the earliest contact tracking reports from a single skilled nursing facility in the United States showed that over half of the residents were hospitalized, and one-third died [10]. The incidence rate for COVID-19–associated death of adults older than 69 years was 13 times higher in people in long-term care than in community living in Ontario, Canada [13]. The Polish government reported that about 9% of all COVID-19 cases in June 2020 were related to infections in long-term care facilities [14]. In European countries, deaths among residents of long-term care facilities accounted for 37–66% of all COVID-related deaths [15]. Despite the significant disease burden, preventive measures also harmed residents’ mental and physical health. The well-being of older residents in long-term care facilities was severely affected [16,17].

Analysis of multiple studies revealed a reduction of ability to perform ADL and, consequently, loss of independence in COVID-19 adult patients after the acute phase of infection [9]. The COVID-19 pandemic caused severe illness and death in many long-term care centers worldwide and shaped long-term care. Vaccinations decreased the risk of a severe clinical course of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities; however, they were insufficient to prevent infection outbreaks [12,13]. This makes people living in long-term care facilities one of the populations most vulnerable to COVID-19 after the pandemic [2]. Trevissón-Redondo et al (2021) [18] indicated that COVID-19 survivors had reduced abilities to perform ADL after recovering from the disease. They studied ADL of 68 residents older than 65 years old and infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). During the disease and convalescence, patients stayed in nursing homes. Functional independence assessed using the Barthel Index (BI) was significantly limited in survivors (mean BI 52.3 points) compared to the period before infection (mean BI 83.2 points). Worsening ability to perform ADL was present in all 10 subdomains of the index. Belli et al (2020) [19] reported that elderly patients hospitalized due to COVID-19 had impaired functional performance after discharge; 67% of patients had BI ≤60 points. Beyond the burden of the disease, older adults were impacted by lockdown restrictions and had restricted access to healthcare services [20].

Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 have diminished quality of life after discharge. Age significantly predicted compromised physical and mental performance after hospitalization [21–23]. The physical and psychical functioning of patients surviving hospitalization or intensive care unit (ICU) admission recovered in the long-term follow-up [24–26].

This study aimed to characterize the evolution of ADL in COVID-19 survivors in long-term institutional care and to determine whether older adults living in nursing or social assistance homes, who are one of the populations most vulnerable to COVID-19, return to a functional status. The study was conducted in the early pandemic phase before there were routine vaccinations against COVID-19.

Material and Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS:

This was a retrospective study conducted among consecutive long-term care facility residents infected with SARS-CoV-2. The study enrolled COVID-19 survivors who were residents of 4 social assistance houses [27] and 1 nursing home [28] from the Wielkopolska region in Poland. Every patient infected with SARS-CoV-2 between April and December 2020 who survived 3 months following resolution of the disease was included in the study. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing from nasopharyngeal swabs. None of the patients was vaccinated against COVID-19. Ability to perform ADL were evaluated at 3 time points: before infection (data retrieved from medical records), directly after recovery, and 3 months after COVID-19.

Collected baseline characteristics included demographics, medical history, and course of COVID-19. Outcomes at baseline, directly after, and 3 months after the disease was evaluated in all patients.

To establish whether COVID-19-associated hospitalization results in persistent worsening of ability to perform ADL, a dataset of the outcome of 49 long-term care residents hospitalized without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection was created. This dataset served as a control group to establish the ADL recovery status of COVID-19 survivors at 3 months.

OUTCOMES:

The primary outcome of the study was BI assessed directly after COVID-19 and at 3 follow-ups. The BI measures the capacity to perform 10 basic ADL and gives a quantitative estimation of the patient’s level of dependency, with scoring from 0 (totally dependent) to 100 (totally independent) in 5-point increments [29]. BI is one of the most used assessment tools for ADL evaluation among patients with COVID-19 [9]. Results were interpreted according to Sinoff and Ore (1997) [30]. BI is relevant for patients across their continuum of critical illness and is a standard tool used to evaluate when someone starts to need personal help. In Poland, the BI evaluation is required to qualify patients for long-term nursing and care services financed by the state. Assessments are routinely performed at least once monthly and in the case of a change of health status [31].

These outcome data were retrospectively collected in all 3-months COVID-19 survivors. Baseline assessment was performed <1 month before COVID-19; the subsequent assessments were performed immediately after recovery and 3 months later.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Demographic characteristics and BI estimates were presented as median (range or 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous variables and expressed as absolute values along with percentages for categorical variables. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of the data.

For the comparison of BI between different follow-up visits, we used one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) or McNemar test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. ANOVA was used to compare BI between hospitalized COVID-19 survivors and controls. All significance tests were two-sided, and

The multivariable logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of persistent worsening in BI. All variables tested with

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS:

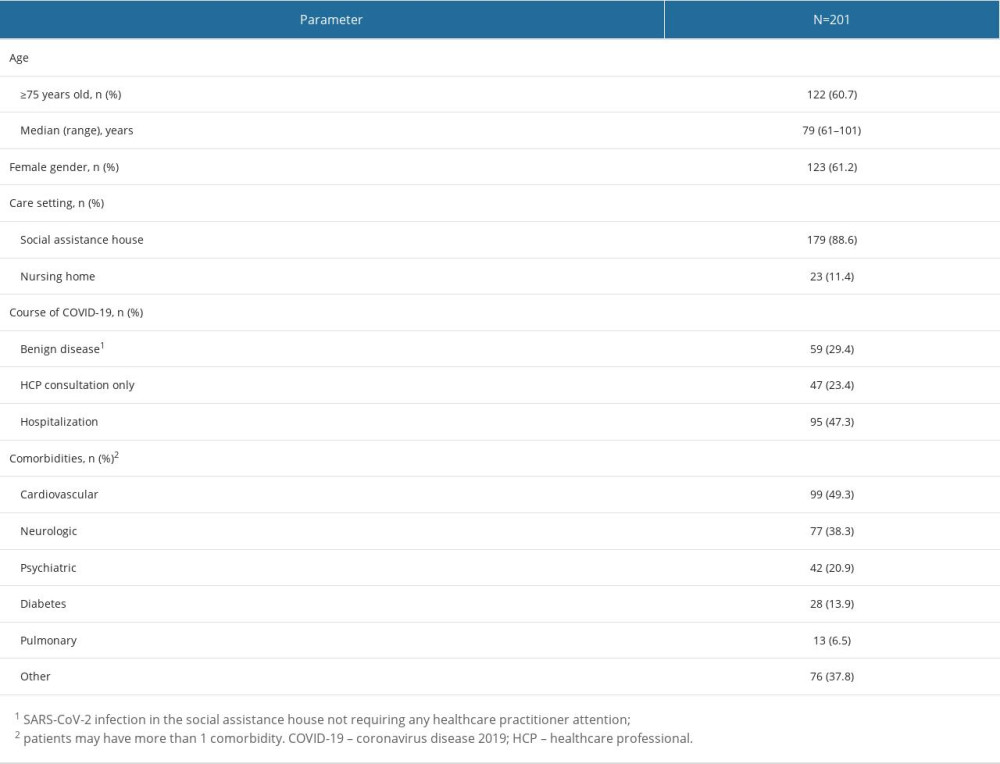

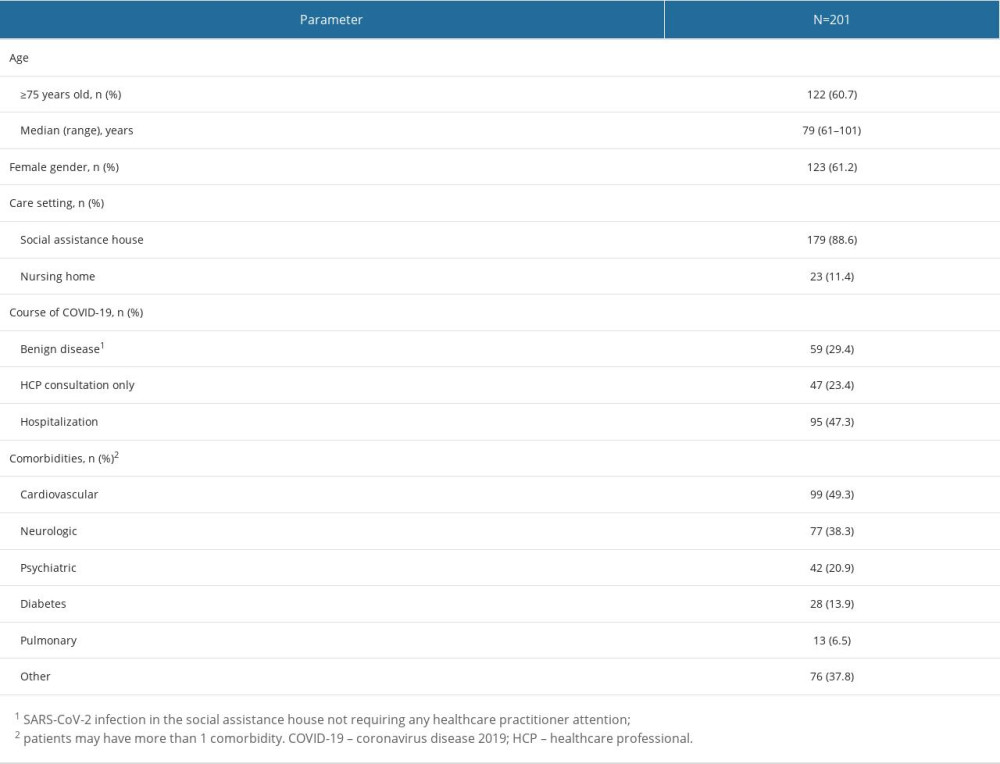

The baseline characteristics of 201 residents of long-term care facilities who survived COVID-19 are given in Table 1. Their median age was 79 years (range 61–101), and 61% were women. The most prevalent comorbidities were cardiovascular diseases, followed by neurologic and psychiatric disorders (Table 1). Similar proportions of patients stayed at long-term care facilities during COVID-19 (53%) and required hospitalization (47%).

CHANGES OF ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING IN THE GENERAL POPULATION:

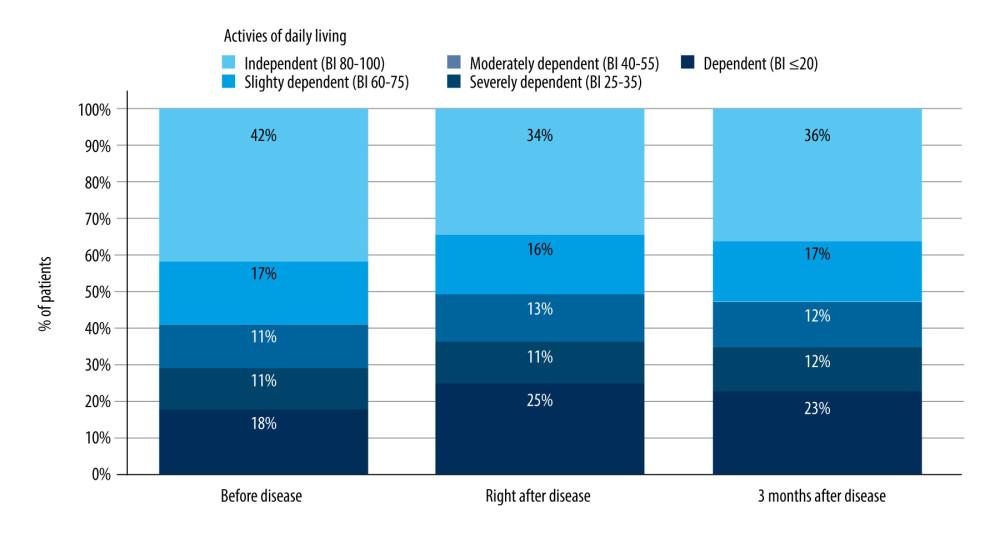

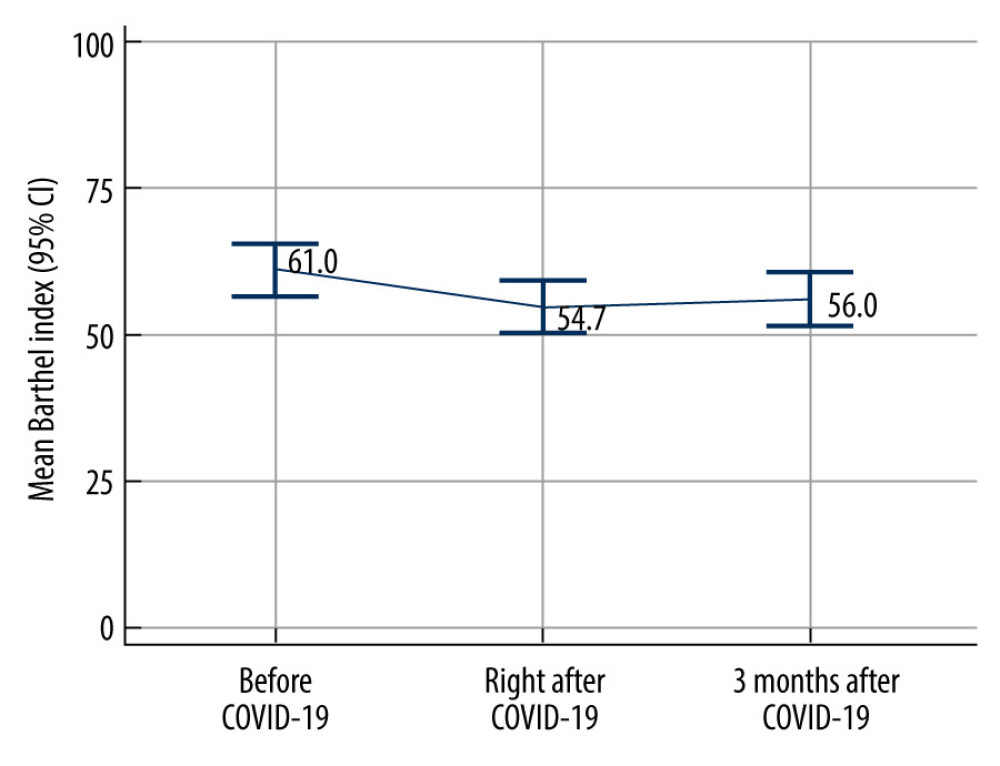

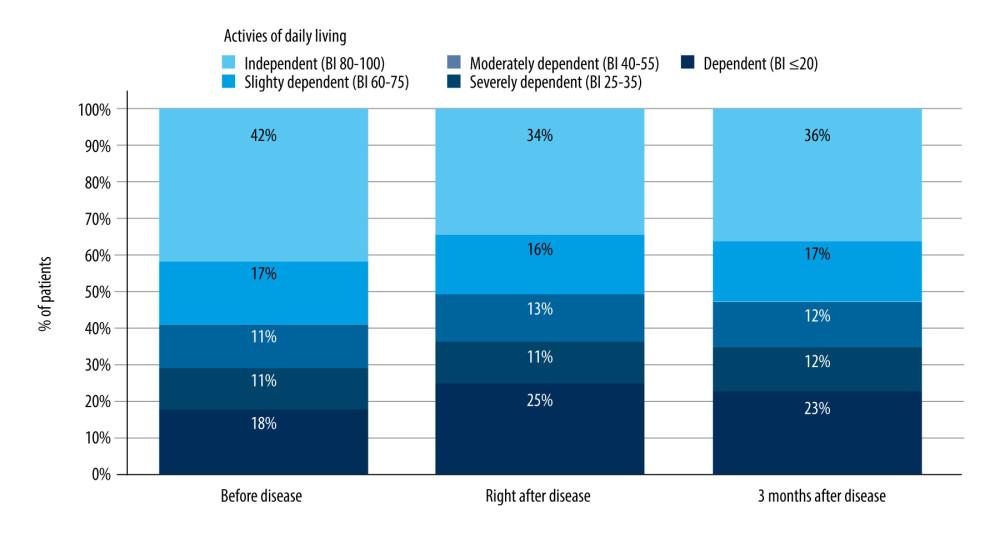

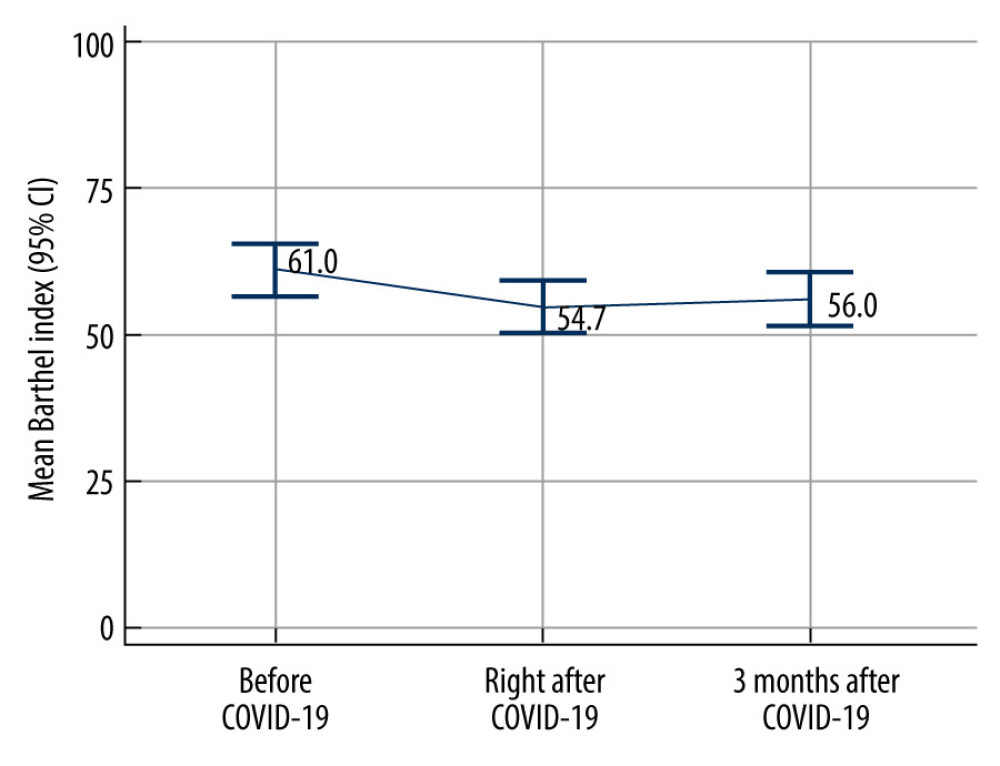

The mean BI before COVID-19 was 61.0 (95% CI: 56.4–65.6). Of all patients studied, 17.9% were dependent (BI score ≤20), 11.4% were severely dependent (BI score 25–35), 11.4% were moderately dependent (BI score 40–55), 17.4% were slightly dependent (BI score 60–75), and 41.8% were independent in performing basic ADL (BI score 80–100) at baseline (Figure 1). Immediately after recovery from COVID-19, the mean BI was 54.7 (95% CI: 49.9–59.4) and 56.0 (95% CI: 51.3–60.8) after 3 months (P<0.0001) (Figure 2). The proportion of patients with impaired functional performance (BI <60) increased by 8.5% (95% CI: 4.6–12.3%; P<0.0001, McNemar test) immediately after recovery from COVID-19 and by 6.5% (95% CI: 3.1–9.9%; P=0.0002, McNemar test) 3 months later (Figure 1).

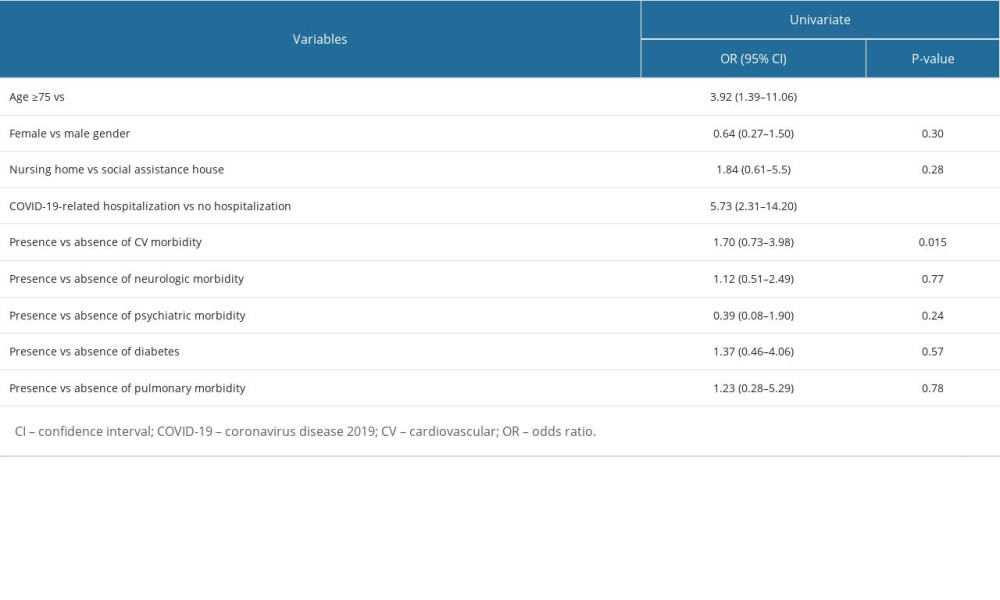

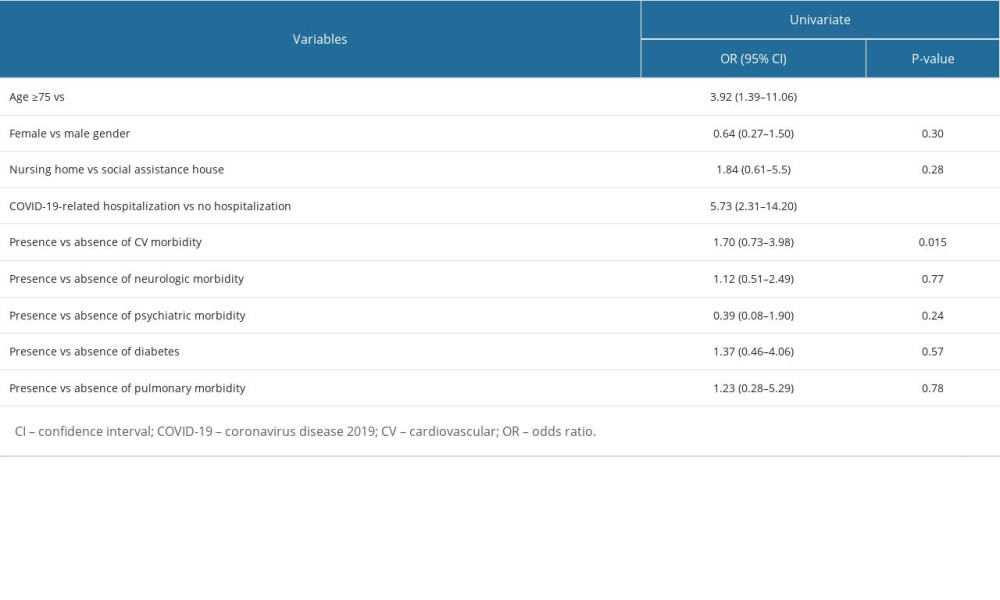

UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS:

A univariate analysis showed that patients with cardiovascular diseases, aged ≥75, and those requiring hospitalization due to COVID-19 had higher odds of persistent worsening in the BI 3 months after recovery compared to the baseline (Table 2). The multivariate logistic regression confirmed the above findings; hospitalization during COVID-19 (P=0.001), increased age (P=0.005), and cardiovascular diseases (P<0.05) were independent predictors of persistent worsening of ADL 3 months after recovery from the infection.

THE IMPACT OF HOSPITALIZATION:

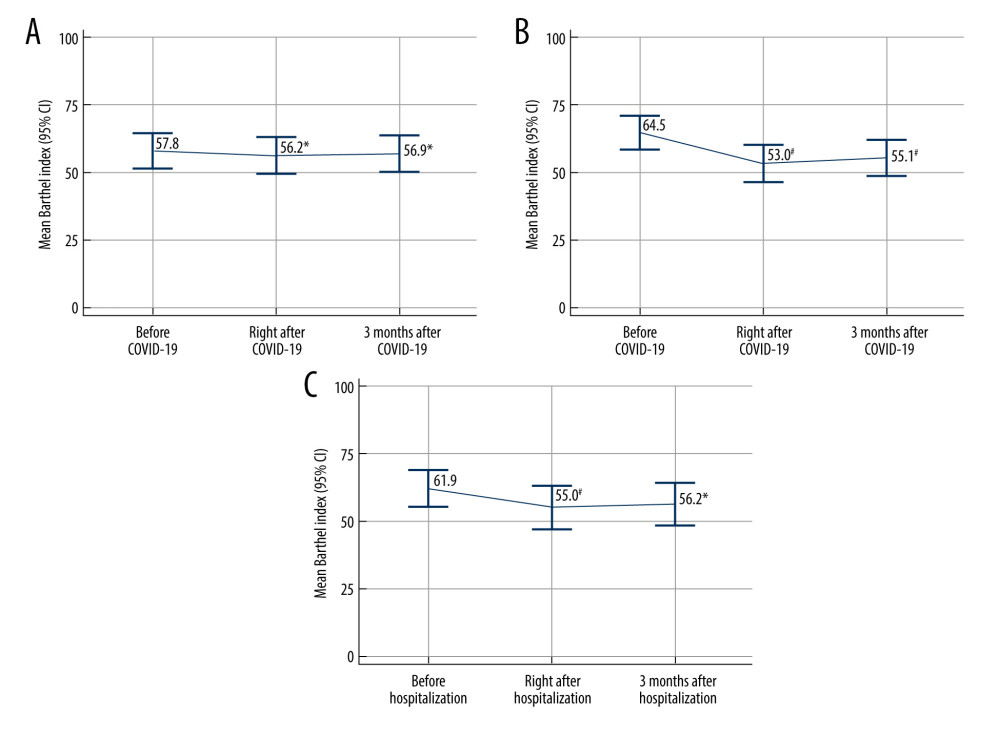

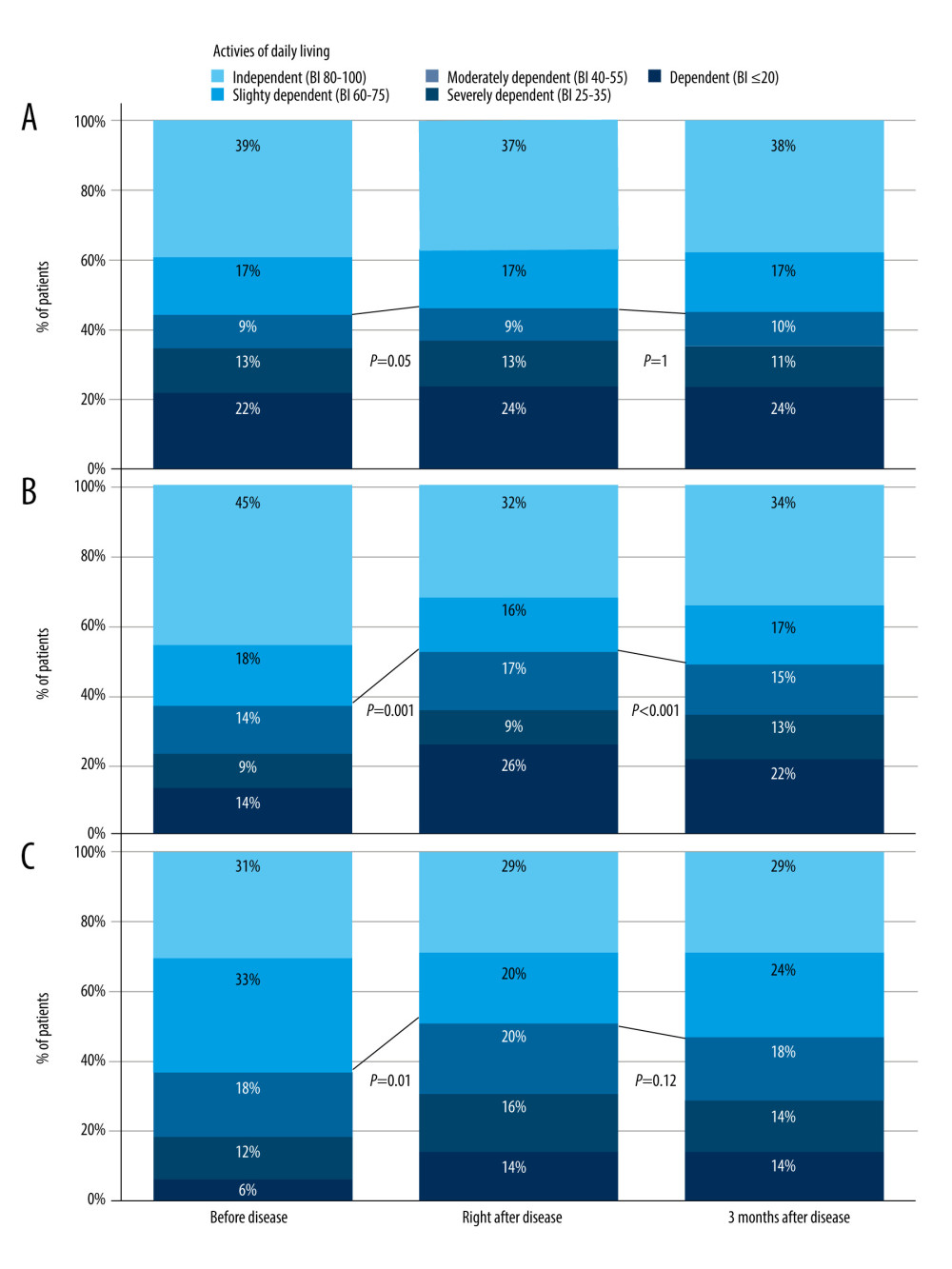

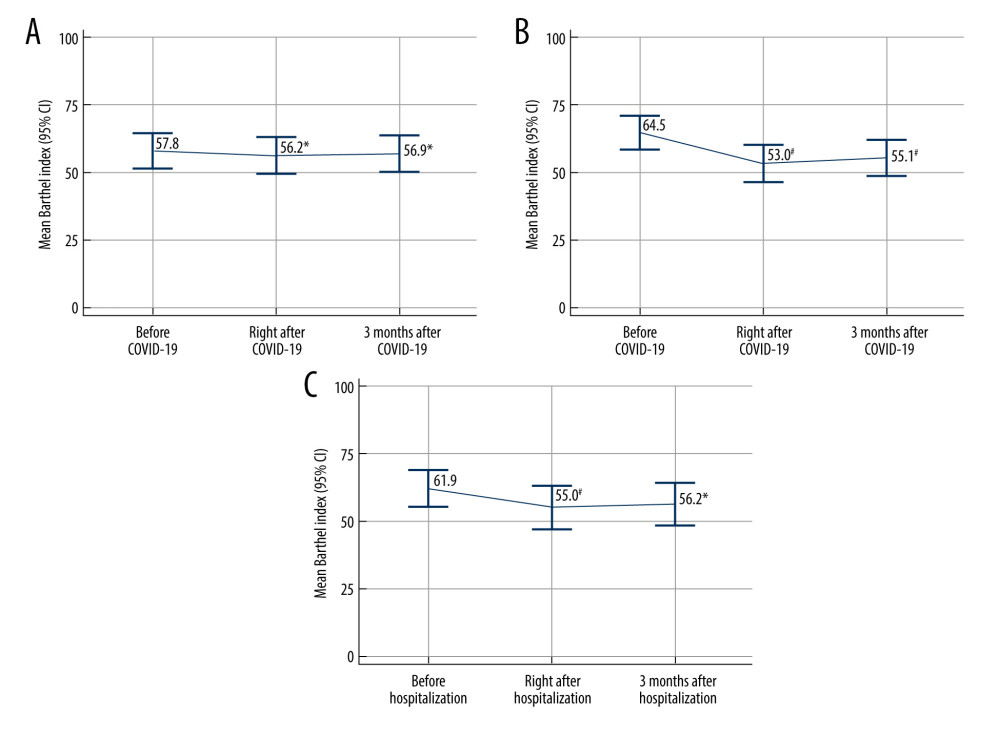

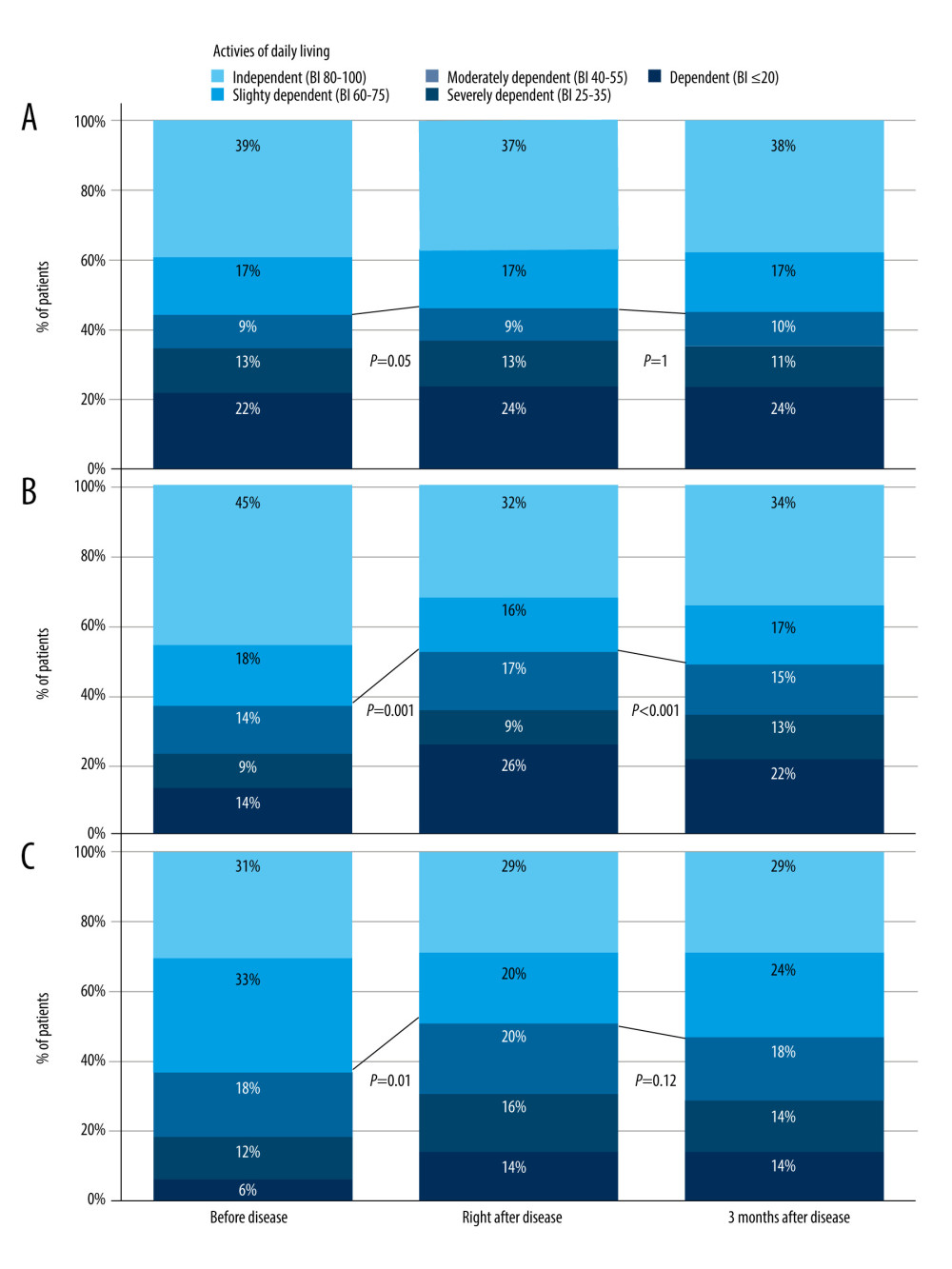

To evaluate the impact of hospitalization on ability to perform ADL, we analyzed the change of BI in subgroups of patients not hospitalized (ie, remained in long-term care) (Figures 3A, 4A) and hospitalized (Figures 3B, 4B) during COVID-19. There were slight changes in the mean BI in non-hospitalized patients. These were statistically significant when analyzing BI as a continuous variable (Figure 3A); however, they did not cause a significant change in the level of patients’ dependence (Figure 4) immediately after recovery from COVID-19 and 3 months later. In the short-term, hospitalization due to COVID-19 led to a significant reduction in the mean BI (Figure 3B) and an increased proportion of patients with limited independence (Figure 4B).

Hospitalization from reasons other than COVID-19 also impaired ability to perform ADL among long-term care residents (Figures 3C, 4C). Comparison of COVID-19-related and unrelated hospitalizations effect on ADL did not reveal statistically significant differences between continuous (P=0.973, ANOVA) and categorical variables (P>0.7734) immediately after discharge and 3 months later.

Discussion

Older adults who are residents of nursing and social assistance homes are not likely to return after COVID-19 to a functional status similar to that before the disease. Not surprisingly, ADL are significantly compromised immediately after recovery from the disease, but they also remained low at follow-up. Within the limitations of the study design, our results suggest that COVID-19 causes a considerable and persistent worsening of functional independence of geriatric patients in long-term care facilities after recovering from the infection.

Elderly patients in institutionalized care facilities have many health conditions increasing the risk of adverse outcomes in COVID-19 [32]. The pandemic has been particularly devastating for elderly people in long-term care [10–13]. Consequently, special protective measures for this population were reinforced [33,34]. European long-term care facilities continued to suffer from COVID-19 in 2022 [35], and it is likely that even after the pandemic, COVID-19 will continue to adversely impact nursing homes and social care institutions. High morbidity, mortality, and social isolation severely affected residents of long-term care facilities. Survivors in institutionalized geriatric care continue to suffer from the disease.

Typically, COVID-19 survivors have a good physical and functional recovery at 1- or 2-year follow-up, returning to their everyday work and life. However, they report problems with mobility, pain, fatigue, mood, and depression compared to age-, sex-, and comorbidity-matched controls [26,36]. In a cross-sectional study, 15% of Americans reported symptoms lasting ≥2 months after a positive SARS-CoV-2 test [37]. Although long-COVID is a well-recognized entity in the general population [38], little is known about post-COVID functioning in long-term care facilities.

Trevissón-Redondo et al [18], for the first time, showed that COVID-19 deteriorates all dimensions of BI in institutionalized older adults. They studied 68 men and women with a mean age of 85.9 years, with a maximum post-infection follow-up of 3 months to exclude the effect of any changes derived from rehabilitation. The mean BI index changed from 83.2 to 52.3 after the disease (

Three months after recovery from the disease, hospitalization, age ≥75 years, and cardiovascular comorbidity were independent predictors of worsening of the BI. COVID-19-related hospitalization can produce a long-term worsening in the frailty of survivors, especially in patients who had reduced quality of life before infection [39,40]. However, most older adults admitted to the intensive care unit due to COVID-19 had no ADL restriction before hospitalization and lived without severe frailty [40]. The majority of patients in this study were primarily independent before admission. Patients requiring hospitalization experienced a greater worsening in ADL compared to those who were convalescent at long-term care facilities. Observed changes indicated a significant worsening in ADL of patients in long-term institutional care. Functioning remained compromised after recovery from the disease. The clinical significance of a decrease in the BI was not studied in patients with COVID-19; however, the minimal clinically important difference of the index was evaluated in other patients. Hsieh et al [41] established that a mean change of BI of 9.25 points (ie, 1.85 on a 20-point scale) could be considered minimally clinically important and beyond measurement error in patients with stroke. Unnanuntana et al 2018 [42] found that 9.8 points is minimally clinically important for assessing the functional recovery of older patients after surgery. The mean decrease of BI right after hospitalization due to COVID-19 reached the minimal clinically important difference established in other groups of patients. However, the threshold was not reached in the control group of hospitalized patients. A slight increase in BI was observed 3 months after the disease in all studied groups.

At the time of the study, the post-COVID-19 rehabilitation program was not yet implemented in Poland [43]. The program was focused on community-dwelling patients and is not continued anymore. It is not likely that residents of long-term care included in the study participated in any rehabilitation program. Staff shortages have affected long-term care facilities in Poland and limited services for older persons. Rehabilitation services were most severely disrupted by the pandemic [44,45]. Thus, similar to the study of Trevissón-Redondo et al [16], our observations can be considered as a natural history of older adult’s functional status deterioration after COVID-19. Reduction of physical function can be addressed with pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. The pandemic initiated the development of early and effective interventions for older adults affected by COVID-19 during and after hospitalization [46,47]. Our study showed that functional dependence in ADL remained common among residents of long-term care facilities. Rehabilitation interventions are offered mainly to persons who require hospitalization. Indeed, their early functional status was more comprised compared to those not hospitalized; however, in the long-term, functioning deteriorated in both groups to a similar level. Thus, residents of long-term care facilities may require rehabilitation programs regardless of the necessity of hospitalization.

In our cohort there was a similar deterioration in the BI 3 months after recovery from the disease in men and women, as previously reported by Trevissón-Redondo et al [18], but females had greater ADL improvement in a large study evaluating care provided in home healthcare [48]. Of note, phenotypes of the post-COVID syndrome in men and women are different, with a predominance of dyspnea in men and fatigue in women [49]. Since sex is one of several variables known to influence the overall immune responses to COVID-19, it would also be associated with recovery from the disease.

This study had several limitations. First, the study design was retrospective, without strict inclusion criteria, which allowed heterogeneity across the sample population. Other limitations include a lack of information about the course of hospitalization; eg, older patients with COVID-19 more frequently require ICU admission than others. The control group, which consisted of patients hospitalized for reasons other than COVID-19 was unmatched, limiting the value of the comparison performed. The effects of COVID-19 on ADL are challenging to distinguish from the lockdown, which severely impacted the elderly population [50].

Conclusions

Long-term care residents may have impaired physical functioning when they recover from COVID-19, even with a non-severe clinical course not requiring hospitalization. Deterioration in ADL may be more considerable in patients who require hospitalization. Our data suggest that early rehabilitation should be considered for all COVID-19 survivors in long-term care, not only those discharged from a hospital. Therefore, there is great demand for tailored rehabilitation programs for COVID-19 survivors in long-term care facilities. This is important since even in the endemic phase, COVID-19 will likely continue to burden residents of long-term care facilities.

Figures

Figure 1. The proportion of patients according to their functioning status. Activities of daily living were classified based on the Barthel Index value at different time points. P values (McNemar test) comparisons of the proportion of patients (n=201) with impaired functioning (Barthel Index <60) vs baseline (before the disease). Figure created with Tableau 2021.4.17 (Tableau Software LCC).

Figure 1. The proportion of patients according to their functioning status. Activities of daily living were classified based on the Barthel Index value at different time points. P values (McNemar test) comparisons of the proportion of patients (n=201) with impaired functioning (Barthel Index <60) vs baseline (before the disease). Figure created with Tableau 2021.4.17 (Tableau Software LCC).  Figure 2. Impairment of activities of daily living of institutionalized care patients after COVID-19. P<0.0001 (ANOVA) for all comparisons (n=201). Data shown as mean values with 95% confidence interval. Figure created with MedCalc v20.121 (MedCalc Software Ltd). CI – confidence interval; COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019.

Figure 2. Impairment of activities of daily living of institutionalized care patients after COVID-19. P<0.0001 (ANOVA) for all comparisons (n=201). Data shown as mean values with 95% confidence interval. Figure created with MedCalc v20.121 (MedCalc Software Ltd). CI – confidence interval; COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019.  Figure 3. Changes in activities of daily living of institutionalized care patients after COVID-19 not requiring hospitalization (n=106) (A); after COVID-19 requiring hospitalization (n=95) (B) and after non-COVID-19-associated hospitalization (n=49); ie, hospitalization for any other reason than COVID-19 (C) * P≤0.05, # P<0.001 (ANOVA) vs baseline; ie, before the disease (A) or hospitalization (B, C). Data are shown as mean values with 95% confidence interval. Figure created with MedCalc v20.121 (MedCalc Software Ltd). CI – confidence interval; COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019.

Figure 3. Changes in activities of daily living of institutionalized care patients after COVID-19 not requiring hospitalization (n=106) (A); after COVID-19 requiring hospitalization (n=95) (B) and after non-COVID-19-associated hospitalization (n=49); ie, hospitalization for any other reason than COVID-19 (C) * P≤0.05, # P<0.001 (ANOVA) vs baseline; ie, before the disease (A) or hospitalization (B, C). Data are shown as mean values with 95% confidence interval. Figure created with MedCalc v20.121 (MedCalc Software Ltd). CI – confidence interval; COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019.  Figure 4. The proportion of patients according to the functioning status in not hospitalized; N=106 (A), hospitalized; N=95 (B), and control; N=49 (C) groups. Activities of daily living were classified based on the Barthel Index value at different time points. P values (McNemar test) comparisons of the proportion of patients with impaired functioning (Barthel Index <60) vs baseline; ie, before disease or hospitalization. Figure created with Tableau 2021.4.17 (Tableau Software LCC). BI – Barthel Index.

Figure 4. The proportion of patients according to the functioning status in not hospitalized; N=106 (A), hospitalized; N=95 (B), and control; N=49 (C) groups. Activities of daily living were classified based on the Barthel Index value at different time points. P values (McNemar test) comparisons of the proportion of patients with impaired functioning (Barthel Index <60) vs baseline; ie, before disease or hospitalization. Figure created with Tableau 2021.4.17 (Tableau Software LCC). BI – Barthel Index. References

1. Giri S, Chenn LM, Romero-Ortuno R, Nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review of challenges and responses: Eur Geriatr Med, 2021; 12(6); 1127-36

2. Thompson DC, Barbu MG, Beiu C, The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on long-term care facilities worldwide: An overview on international issues: Biomed Res Int, 2020; 2020; 8870249

3. Chang KC, Strong C, Pakpour AH, Factors related to preventive COVID-19 infection behaviors among people with mental illness: J Formos Med Assoc, 2020; 119(12); 1772-80

4. Numbers K, Brodaty H, The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia: Nat Rev Neurol, 2021; 17(2); 69-70

5. Liu L, Ni SY, Yan W, Mental and neurological disorders and risk of COVID-19 susceptibility, illness severity and mortality: A systematic review, meta-analysis and call for action: EClinicalMedicine, 2021; 40; 101111

6. Medicine Io: Providing Healthy and Safe Foods As We Age: Workshop Summary, 2010; 192, Washington, DC, The National Academies Press

7. Sowa-Kofta A, Marcinkowska I, Rudzik-Sierdzińska A, Mackeviciute R: Ageing policies – access to services in different Member States, 2021, Luxemburg, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament

8. : How much care will you need?, 2020, Internet: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [22.06.2023]; Available from:https://acl.gov/ltc/basic-needs/how-much-care-will-you-need

9. Pizarro-Pennarolli C, Sánchez-Rojas C, Torres-Castro R, Assessment of activities of daily living in patients post COVID-19: A systematic review: PeerJ, 2021; 9; e11026

10. McMichael TM, Currie DW, Clark S, Epidemiology of COVID-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington: N Engl J Med, 2020; 382(21); 2005-11

11. Machado CJ, Pereira CCA, Viana BM, Estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on mortality of institutionalized elderly in Brazil: Cien Saude Colet, 2020; 25(9); 3437-44

12. Cabrero GR, The coronavirus crisis and its impact on residential care homes for the elderly in Spain: Cien Saude Colet, 2020; 25(6); 1996

13. Fisman DN, Bogoch I, Lapointe-Shaw L, Risk factors associated with mortality among residents with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in long-term care facilities in Ontario, Canada: JAMA Netw Open, 2020; 3(7); e2015957

14. Sowa-Kofta A, Responding to the COVID-19 in residential long-term care in Poland: What has been done to increase safety of the elderly: Journal of Social Policy, 2020; 141-50

15. Danis K, Fonteneau L, Georges S, High impact of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, suggestion for monitoring in the EU/EEA, May 2020: Euro Surveill, 2020; 25(22); 2000956

16. Van der Roest HG, Prins M, van der Velden C, The impact of COVID-19 measures on well-being of older long-term care facility residents in the Netherlands: J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2020; 21(11); 1569-70

17. Martínez-Garcia M, Sansano-Sansano E, Castillo-Hornero A, Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A population study: Sci Rep, 2022; 12(1); 12543

18. Trevissón-Redondo B, López-López D, Pérez-Boal E, Use of the Barthel Index to assess activities of daily living before and after SARS-COVID 19 infection of institutionalized nursing home patients: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(14); 7258

19. Belli S, Balbi B, Prince I, Low physical functioning and impaired performance of activities of daily life in COVID-19 patients who survived hospitalisation: Eur Respir J, 2020; 56(4); 2002096

20. Brooke J, Dunford S, Clark M, Older adult’s longitudinal experiences of household isolation and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Int J Older People Nurs, 2022; 17(5); e12459

21. Vlake JH, Wesselius S, van Genderen ME, van Bommel J, Psychological distress and health-related quality of life in patients after hospitalization during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single-center, observational study: PLoS One, 2021; 16(8); e0255774

22. Figueiredo EAB, Silva WT, Tsopanoglou SP, The health-related quality of life in patients with post-COVID-19 after hospitalization: A systematic review: Rev Soc Bras Med Trop, 2022; 55; e0741

23. Gamberini L, Mazzoli CA, Sintonen H, Quality of life of COVID-19 critically ill survivors after ICU discharge: 90 days follow-up: Qual Life Res, 2021; 30(10); 2805-17

24. Gamberini L, Mazzoli CA, Prediletto I, Health-related quality of life profiles, trajectories, persistent symptoms and pulmonary function one year after ICU discharge in invasively ventilated COVID-19 patients, a prospective follow-up study: Respir Med, 2021; 189; 106665

25. Daher A, Cornelissen C, Hartmann NU, Six months follow-up of patients with invasive mechanical ventilation due to COVID-19 related ARDS: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021; 18(11); 5861

26. Huang L, Li X, Gu X, Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: A longitudinal cohort study: Lancet Respir Med, 2022; 10(9); 863-76

27. Statistics Poland: Terms used in official statistics: Social assistance house, 2004, Internet: Statistics Poland [cited 12.12.2022] Available from: https://stat.gov.pl/en/metainformation/glossary/terms-used-in-official-statistics/1353,term.html

28. Statistics Poland, Terms used in official statistics: Nursing Homes: Internet: Statistics Poland, 2016 [cited 12.12.2022]; Available from:https://stat.gov.pl/en/metainformation/glossary/terms-used-in-official-statistics/3966,term.html

29. Wade DT, Collin C, The Barthel ADL Index: A standard measure of physical disability?: Int Disabil Stud, 1988; 10(2); 64-67

30. Sinoff G, Ore L, The Barthel activities of daily living index: Self-reporting versus actual performance in the old-old (> or = 75 years): J Am Geriatr Soc, 1997; 45(7); 832-36

31. : Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 22 listopada 2013 r. w sprawie świadczeń gwarantowanych z zakresu świadczeń pielęgnacyjnych i opiekuńczych w ramach opieki długoterminowej. Dz.U. 2013 poz. 1480, 2013, Parliament of Poland [cited 11. 12. 2022]; Available from: [in Polish]https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20130001480

32. Araújo MPD, Nunes VMA, Costa LA, Health conditions of potential risk for severe COVID-19 in institutionalized elderly people: PLoS One, 2021; 16(1); e0245432

33. , Prevention and control of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, Internet: European Centre for Disease Prevention Control [cited 23.12.2022]; Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/coronavirus/threats-and-outbreaks/covid-19/prevention-and-control/LTCF

34. : Infection prevention and control guidance for long-term care facilities in the context of COVID-19, 2021, Internet: World Health Organization [cited 23.12.2022]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331508/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC_long_term_care-2020.1-eng.pdf

35. : Surveillance data from public online national reports on COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, 2022, Internet: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [cited 23.12.2022]; Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/coronavirus/threats-and-outbreaks/covid-19/prevention-and-control/LTCF-data

36. Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: A longitudinal cohort study: Lancet, 2021; 398(10302); 747-58

37. Perlis RH, Santillana M, Ognyanova K, Prevalence and correlates of long COVID symptoms among US adults: JAMA Network Open, 2022; 5(10); e2238804

38. O’Mahoney LL, Routen A, Gillies C, The prevalence and long-term health effects of long COVID among hospitalised and non-hospitalised populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis: eClinicalMedicine, 2023; 55; 101762

39. Covino M, Russo A, Salini S, Long-term effects of hospitalization for COVID-19 on frailty and quality of life in older adults ≥80 years: J Clin Med, 2022; 11(19); 5787

40. Bruno RR, Wernly B, Flaatten H, The association of the activities of daily living and the outcome of old intensive care patients suffering from COVID-19: Ann Intensive Care, 2022; 12(1); 26

41. Hsieh YW, Wang CH, Wu SC, Establishing the minimal clinically important difference of the Barthel index in stroke patients: Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 2007; 21(3); 233-38

42. Unnanuntana A, Jarusriwanna A, Nepal S, Validity and responsiveness of Barthel index for measuring functional recovery after hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture: Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 2018; 138(12); 1671-77

43. : Znamy szczegóły programu rehabilitacji po przebytej chorobie COVID-19, 2021, Internet: National Health Fund [cited 23.12.2022]; Available from: [in Polish]https://www.nfz.gov.pl/aktualnosci/aktualnosci-centrali/znamy-szczegoly-programu-rehabilitacji-po-przebytej-chorobie-covid-19,7959.html

44. : Staff Shortages in Social Services across Europe, 2022, Internet: Federation of European Social Employers [cited 23.12.2022]; Available from: https://socialemployers.eu/files/doc/Staff%20shortages%20in%20social%20services%20across%20Europe.pdf

45. Reddy A, Resnik L, Freburger J, Rapid changes in the provision of rehabilitation care in post-acute and long-term care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic: J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2021; 22(11); 2240-44

46. Sagarra-Romero L, Viñas-Barros A, COVID-19: Short and long-term effects of hospitalization on muscular weakness in the elderly: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020; 17(23); 8715

47. Zana S, Vecchiato C, Dussin M, Multicomponent rehabilitation after COVID-19 for nursing home residents: J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2021; 22(7); 1358-60

48. Osakwe ZT, Larson E, Andrews H, Shang J, Activities of daily living of home healthcare patients: Home Healthc Now, 2019; 37(3); 165-73

49. Ganesh R, Grach SL, Ghosh AK, The female-predominant persistent immune dysregulation of the post-COVID syndrome: Mayo Clinic Proc, 2022; 97(3); 454-64

50. Bloom I, Zhang J, Hammond J, Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on community-dwelling older adults: A longitudinal qualitative study of participants from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study: PLoS One, 2022; 17(10); e0275486

Figures

Figure 1. The proportion of patients according to their functioning status. Activities of daily living were classified based on the Barthel Index value at different time points. P values (McNemar test) comparisons of the proportion of patients (n=201) with impaired functioning (Barthel Index <60) vs baseline (before the disease). Figure created with Tableau 2021.4.17 (Tableau Software LCC).

Figure 1. The proportion of patients according to their functioning status. Activities of daily living were classified based on the Barthel Index value at different time points. P values (McNemar test) comparisons of the proportion of patients (n=201) with impaired functioning (Barthel Index <60) vs baseline (before the disease). Figure created with Tableau 2021.4.17 (Tableau Software LCC). Figure 2. Impairment of activities of daily living of institutionalized care patients after COVID-19. P<0.0001 (ANOVA) for all comparisons (n=201). Data shown as mean values with 95% confidence interval. Figure created with MedCalc v20.121 (MedCalc Software Ltd). CI – confidence interval; COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019.

Figure 2. Impairment of activities of daily living of institutionalized care patients after COVID-19. P<0.0001 (ANOVA) for all comparisons (n=201). Data shown as mean values with 95% confidence interval. Figure created with MedCalc v20.121 (MedCalc Software Ltd). CI – confidence interval; COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019. Figure 3. Changes in activities of daily living of institutionalized care patients after COVID-19 not requiring hospitalization (n=106) (A); after COVID-19 requiring hospitalization (n=95) (B) and after non-COVID-19-associated hospitalization (n=49); ie, hospitalization for any other reason than COVID-19 (C) * P≤0.05, # P<0.001 (ANOVA) vs baseline; ie, before the disease (A) or hospitalization (B, C). Data are shown as mean values with 95% confidence interval. Figure created with MedCalc v20.121 (MedCalc Software Ltd). CI – confidence interval; COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019.

Figure 3. Changes in activities of daily living of institutionalized care patients after COVID-19 not requiring hospitalization (n=106) (A); after COVID-19 requiring hospitalization (n=95) (B) and after non-COVID-19-associated hospitalization (n=49); ie, hospitalization for any other reason than COVID-19 (C) * P≤0.05, # P<0.001 (ANOVA) vs baseline; ie, before the disease (A) or hospitalization (B, C). Data are shown as mean values with 95% confidence interval. Figure created with MedCalc v20.121 (MedCalc Software Ltd). CI – confidence interval; COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019. Figure 4. The proportion of patients according to the functioning status in not hospitalized; N=106 (A), hospitalized; N=95 (B), and control; N=49 (C) groups. Activities of daily living were classified based on the Barthel Index value at different time points. P values (McNemar test) comparisons of the proportion of patients with impaired functioning (Barthel Index <60) vs baseline; ie, before disease or hospitalization. Figure created with Tableau 2021.4.17 (Tableau Software LCC). BI – Barthel Index.

Figure 4. The proportion of patients according to the functioning status in not hospitalized; N=106 (A), hospitalized; N=95 (B), and control; N=49 (C) groups. Activities of daily living were classified based on the Barthel Index value at different time points. P values (McNemar test) comparisons of the proportion of patients with impaired functioning (Barthel Index <60) vs baseline; ie, before disease or hospitalization. Figure created with Tableau 2021.4.17 (Tableau Software LCC). BI – Barthel Index. Tables

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Table 1. Patient characteristics. Table 2. Univariate analysis for factors associated with worsening in the Barthel Index persisting 3 months after COVID-19 in comparison to the baseline.

Table 2. Univariate analysis for factors associated with worsening in the Barthel Index persisting 3 months after COVID-19 in comparison to the baseline. Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Table 1. Patient characteristics. Table 2. Univariate analysis for factors associated with worsening in the Barthel Index persisting 3 months after COVID-19 in comparison to the baseline.

Table 2. Univariate analysis for factors associated with worsening in the Barthel Index persisting 3 months after COVID-19 in comparison to the baseline. In Press

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952