20 March 2023: Clinical Research

An Online Questionnaire-Based Survey of 1076 Individuals in Poland to Identify the Prevalence of Ophthalmic Symptoms in Autumn 2022

Agnieszka KamińskaDOI: 10.12659/MSM.939622

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e939622

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Vision health affects functioning in society, and the ability to learn and work. Ophthalmic symptoms may be caused by eye diseases, but also by environmental or lifestyle factors. This online questionnaire-based survey aimed to identify the prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms in 1076 individuals in Poland, as well as to identify factors associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: An online questionnaire-based survey was carried out in December 2022 on a representative sample of 1076 adult Poles. Non-probability quota sampling was used. Respondents were asked about the presence of 16 different eye symptoms and vision problems in the last 30 days. The presence of ophthalmic symptoms was self-declared. Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS package version 28.

RESULTS: More than half of the respondents (57.8%) had at least 1 ophthalmic symptom in the last 30 days. Burning and stinging eyes (21.6%) and dry eyes (18.9%) were the most common ophthalmic symptoms declared by the respondents. Moreover, 21.3% of respondents reported vision deterioration in the last 30 days. Out of 10 different factors analyzed in this study, female gender, living in rural areas or small cities (below 100 000 inhabitants), living with at least 1 other person, having low economic status, having chronic diseases, and wearing spectacles/contact lenses were significantly associated (P<0.05) with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days.

CONCLUSIONS: This study revealed a high prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms among adults in Poland in autumn 2022. Public health interventions are needed to improve eye health.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Eye Diseases, Poland, Signs and Symptoms, Vision Disorders, Adult, Humans, Female, Prevalence, Surveys and Questionnaires, Dry Eye Syndromes, Contact Lenses

Background

Vision is the most dominant of the human senses [1]. Vision health affects functioning in society, and the ability to learn and work [1,2]. The visual system consists of 2 main components: the eye (the sensory organ) and parts of the central nervous system (including the retina, optic nerve, optic tract, and visual cortex in the brain) [3]. Vision problems are mostly caused by eye conditions and disorders, but neurological disorders (including neuropathies, transient ischemic attack, and stroke) may also lead to vision problems [4,5].

Eye disorders and diseases are a wide group of conditions that can affect vision health and cause vision impairment and blindness [5]. The most common eye diseases are cataracts, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, and dry eye syndrome [6]. Many eye diseases have no symptoms for a long time (eg, glaucoma) [7]. Regular medical checkups including eye exams are crucial for the early detection of eye diseases [8]. Due to the long course without symptoms, patients often visit an ophthalmologist in the advanced stage of disease, when eye symptoms and vision problems worsen [5,7,8]. Contrary to chronic eye diseases, acute inflammatory diseases like hordeolum and chalazion, lead to the occurrence of eye symptoms, prompting patients to urgently visit an ophthalmologist [9].

In addition to eye disorders and diseases, ophthalmic symptoms may be also caused by environmental or lifestyle factors that affect vision and eye health [10–13]. Irritants present in the external environment can cause ocular surface inflammation and eye irritation that leads to dryness, itchiness, and a burning sensation [10]. Exposure to air pollution, especially ozone, nitric dioxide, and particulate matter can lead to toxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammation of the ocular surface and eye symptoms like dry eye syndrome and burning and tearing eyes [11]. Seasonal differences in light exposure, especially in fall/winter, may also affect eye health and vision [12]. Moreover, indoor environments, including temperature and humidity indoors, lighting, and viewing distance can also lead to eye symptoms and vision problems [13].

Lifestyle also has an impact on eye health and vision [4,5,14]. Computer vision syndrome (CVS) is a term commonly used to describe a set of symptoms resulting from long-term work on a digital device, including computers, tablets, and smartphones [15]. A wide variety of eye symptoms may be presented in CVS, including internal ocular symptoms like stain and ache, external ocular symptoms like dryness, irritation, or burning, as well as visual symptoms like blurred or double vision [15]. Eye care behaviors like limiting screen time, eye lubricating, and taking regular breaks when reading or working can reduce ophthalmic symptoms [5].

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected daily habits, including remote work, spending time indoors, and smartphone use, which may also lead to an increase in the prevalence of eye symptoms and vision problems [16,17]. Different authors around the world have used cross-sectional methods (including online questionnaire-based surveys) to assess the prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms, including eye strain, dry eye symptoms, or symptoms of red eyes [18–20]. Nationwide representative data on ophthalmic symptoms after the pandemic onset can inform healthcare professionals and policymakers on research and educational and organizational needs related to eye care and related healthcare services [5,18]. However, there is a lack of representative data on the prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms in Poland, which is one of the biggest European countries, with more than 38 million inhabitants [21].

Therefore, this online questionnaire-based survey aimed to identify the prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms in 1076 individuals in Poland, as well as to identify factors associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms.

Material and Methods

ETHICS:

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (decision number 154/2022 issued by the Ethics Committee at the Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education in Warsaw). Participation in this survey was voluntary and the datasets generated were anonymous. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

SURVEY DESIGN AND POPULATION:

This online questionnaire-based survey was carried out from December 9 through December 12, 2022. Data were collected using computer-assisted web interviews (CAWI) by the Nationwide Research Panel Ariadna (an opinion research company) on behalf of the authors, who provided the scientific context of this study [22–24]. Respondents were recruited via a dedicated web research platform (managed by the opinion research company) from over 100 000 registered users [22]. Non-probability quota sampling was used, and the stratification model included gender, age, and place of residence. Sample size and demographic variables (stratification) were based on the public demographic registry managed by Statistics Poland [25]. All the scientific procedures were performed by the authors, and the opinion research company was contracted only for data collection, which is a commonly used approach to receive nationwide representative data.

SURVEY ITEMS:

The survey was available online on the web research platform. The survey items included knowledge questions about eye diseases, ophthalmic symptoms, eye care behaviors, and eye examinations, as well as sociodemographic characteristics.

Respondents were asked about the presence of 16 different ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days, using the following question: “In the last 30 days, have you had any of the eye symptoms or vision problems listed below? (indicate all that apply): (1) vision deterioration; (2) blurred vision; (3) burning and stinging eyes; (4) bloodshot eyes (or red eyes); (5) dry eyes; (6) excessive tearing; (7) eye pain; (8) hypersensitivity to light (photophobia); (9) night vision problem; (10) tunnel vision (peripheral vision loss); (11) flashes of light in the field of vision; (12) swelling of the eyes or around the eyes; (13) letters and words disappear while reading; (14) color vision deficiency (color blindness); (15) reduced contrast sensitivity; (16) a dark spot in the central field of view “; with 2 possible answers: yes or no.

The presence of ophthalmic symptoms was self-declared and was not verified by eye examination or medical records. However, online questionnaire-based surveys were previously widely used to assess the prevalence of eye symptoms and vision problems (mostly dry eye syndrome) in different populations [18,19,26].

DATA ANALYSIS:

Crude data obtained during the survey were analyzed by the authors with the SPSS package version 28 (USA: IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Frequencies and proportions were used to present the distribution of categorical variables. Cross-tables along with a chi-squared test were used to compare categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were carried out to identify factors associated with the presence of eye symptoms and vision problems in the last 30 days. Self-reported presence of eye symptoms and vision problems was defined as the dependent variable. Moreover, 10 independent variables (including 8 sociodemographic variables, health status, and wearing spectacles or contact lenses) were included in the models. The strength of association was presented with an odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The statistical significance level was based on the criterion

Results

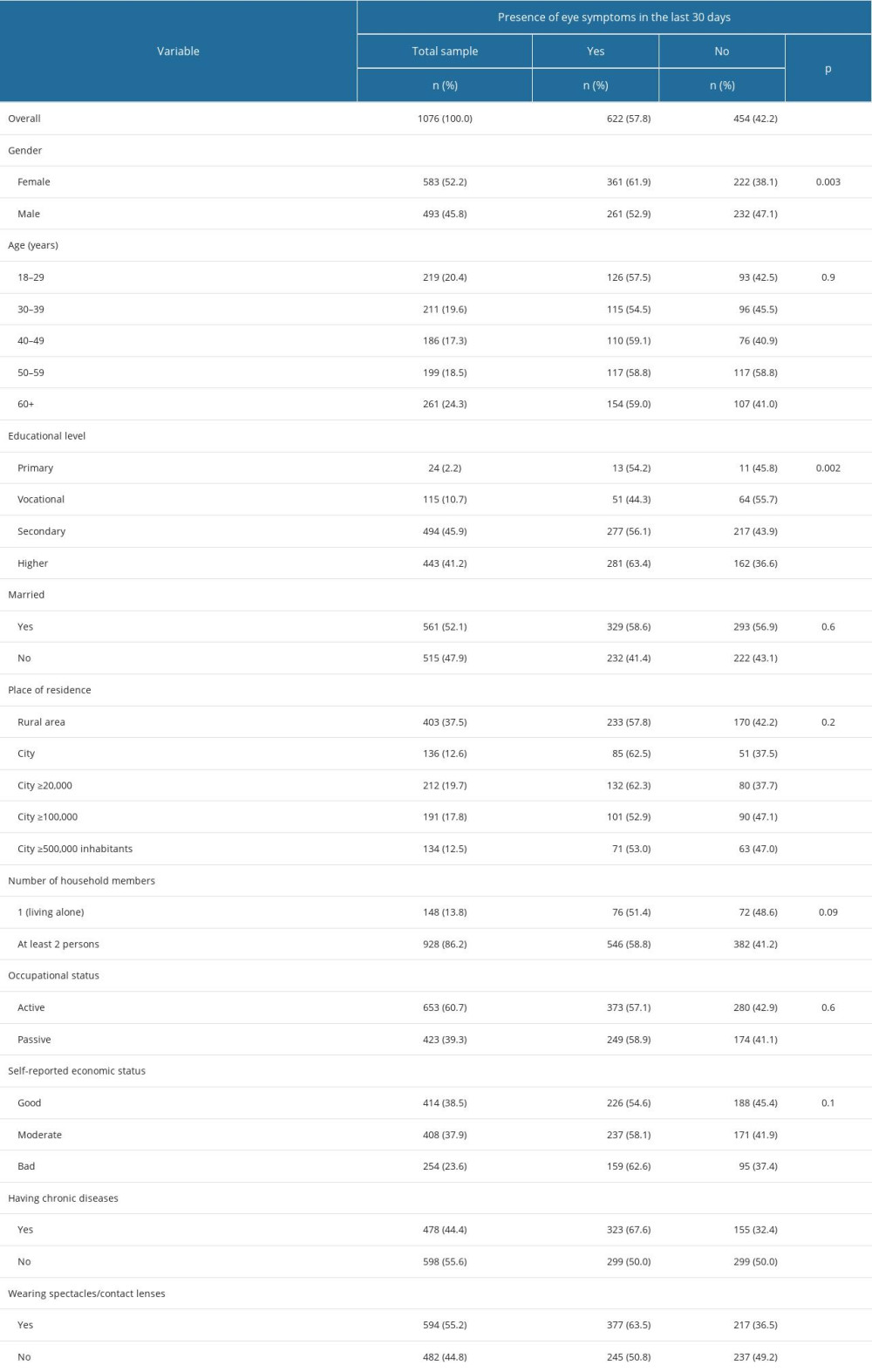

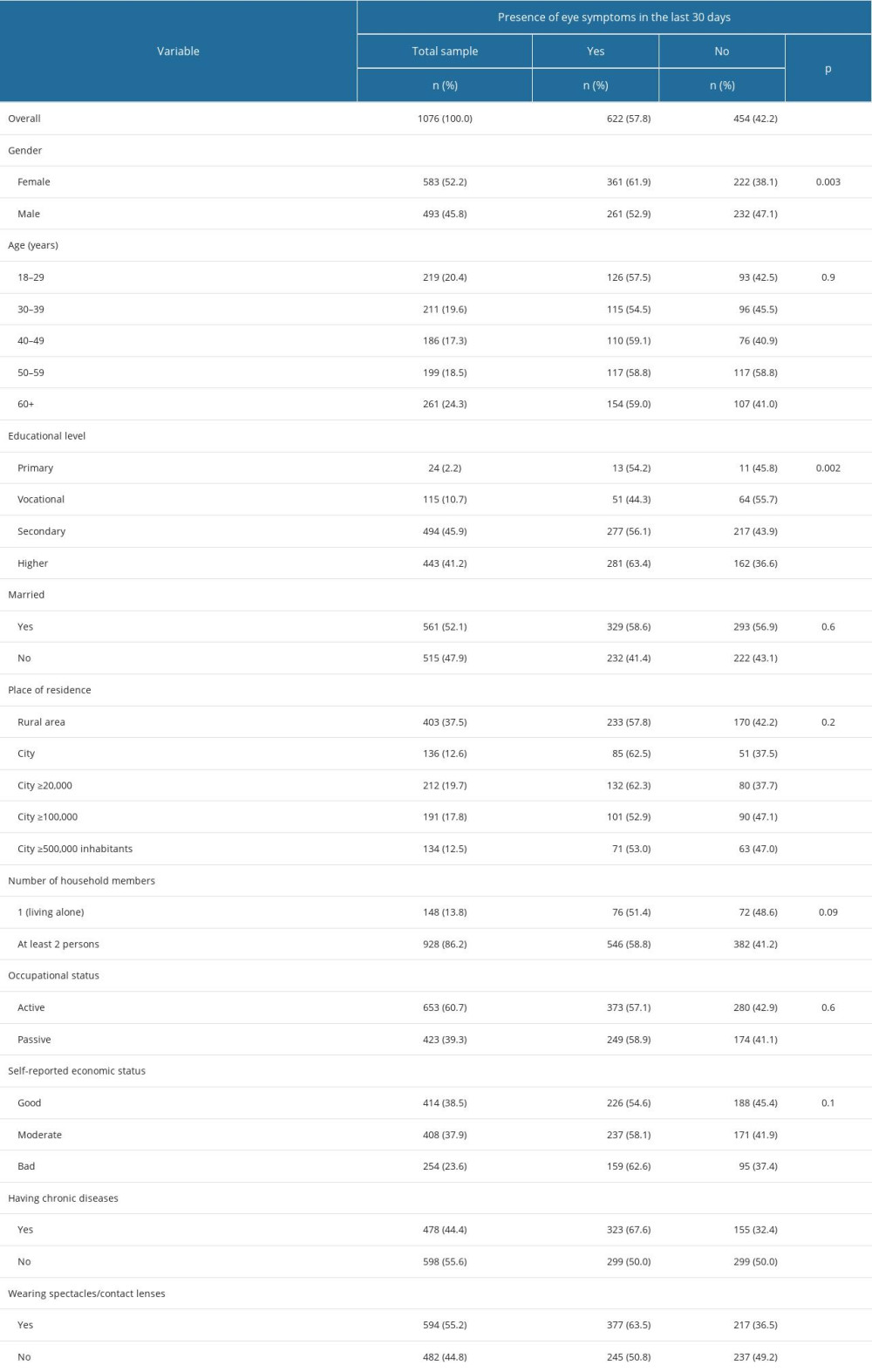

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY POPULATION BY THE PRESENCE OF OPHTHALMIC SYMPTOMS:

Characteristics of the study population by the presence of ophthalmic symptoms are presented in Table 1. More than half of the respondents (57.8%) had eye symptoms or vision problems in the last 30 days (Table 1). Females more often declared the presence of ophthalmic symptoms and vision problems than males (P=0.003). The highest prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms was among those with vocational education (55.7%; P=0.002). Over two-thirds of respondents with chronic diseases declared that they had ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days, compared to 50.0% among healthy individuals (P<0.001). Moreover, those who wore spectacles/contact lenses more often declared that they had ophthalmic symptoms (63.5% vs 50.8%; P<0.001).

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC DIFFERENCES IN THE PREVALENCE OF OPHTHALMIC SYMPTOMS AMONG ADULTS IN POLAND:

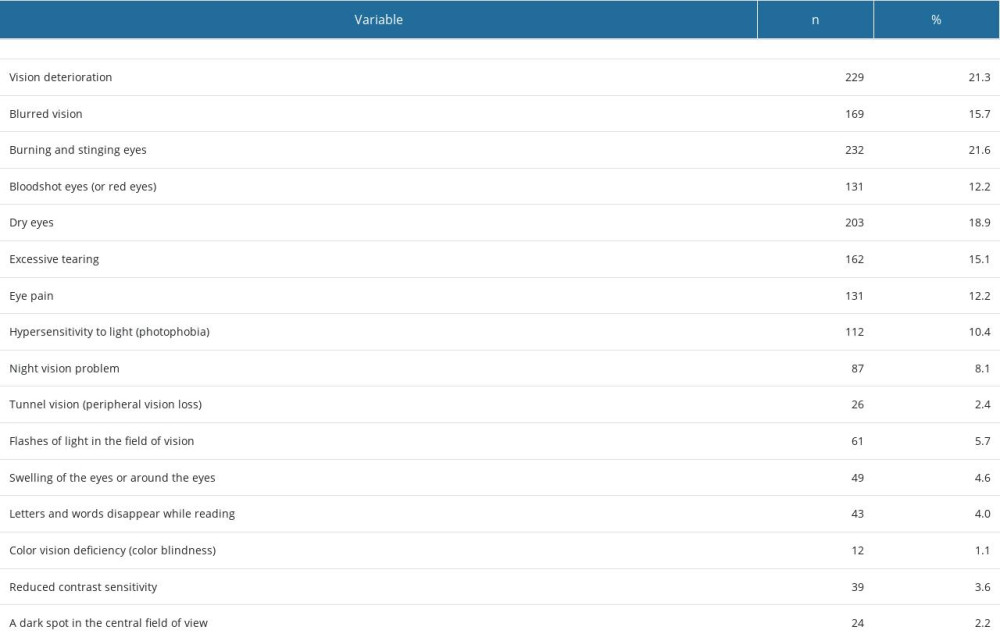

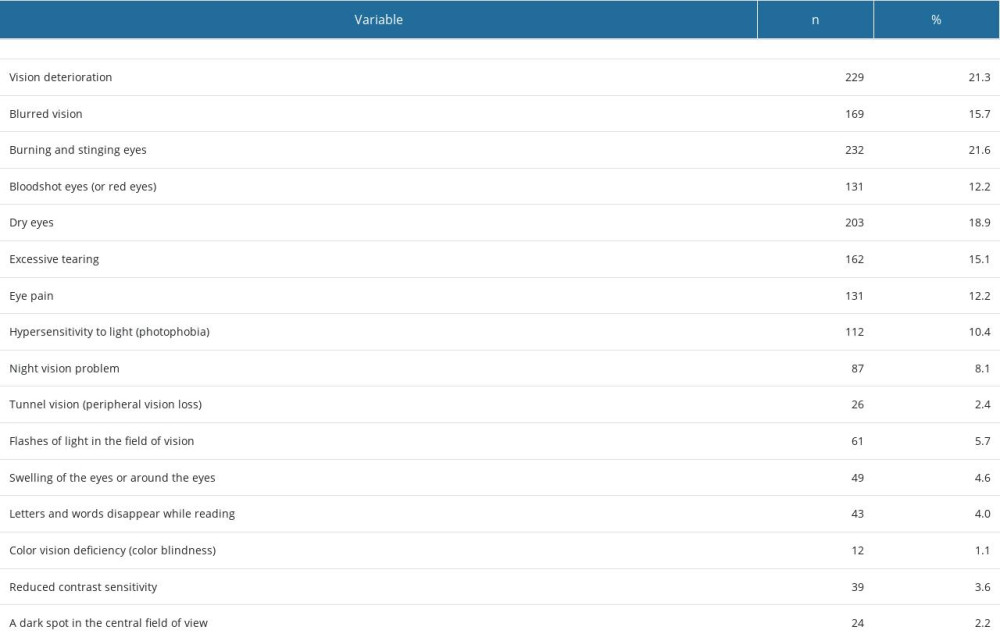

Burning and stinging eyes were the most common ophthalmic symptoms (21.6%) declared by the respondents (Table 2). Moreover, 21.3% of respondents reported vision deterioration in the last 30 days. Among the respondents, 18.9% reported symptoms of dry eyes, and 15.7% had blurred vision in the last 30 days (Table 2). Excessive tearing was reported by 15.1% of respondents, and 12.2% had eye pain or bloodshot eyes/red eyes in the last 30 days. One-tenth of respondents reported hypersensitivity to light (photophobia). Moreover, 8.1% had a night vision problem and 5.7% of respondents had flashes of light in the field of vision (Table 2). The other 6 ophthalmic symptoms analyzed in the study were reported by less than 5% of respondents (Table 2).

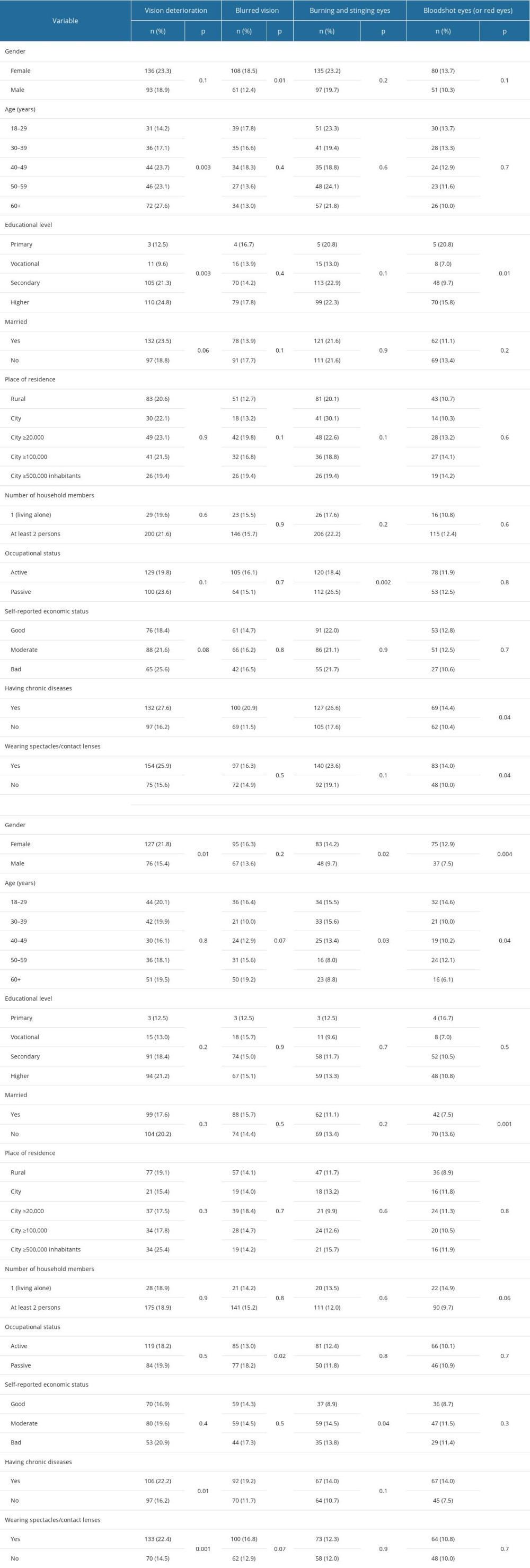

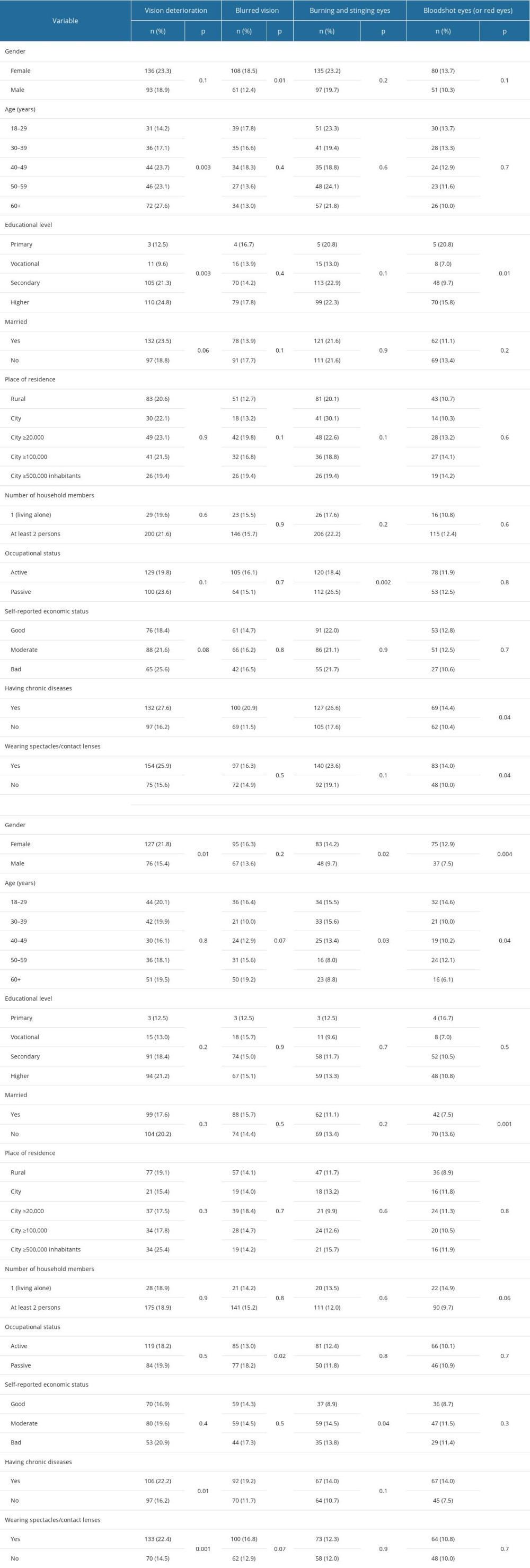

Females more often than males declared that in the last 30 days they had blurred vision (18.5% vs 12.4%; P=0.01), dry eyes (21.8% vs 15.4%; P=0.01), eye pain (14.2% vs 9.7%), or hypersensitivity to light (photophobia) (12.9% vs 7.5%; P=0.004). The prevalence of vision deterioration in the last 30 days increased with the age (P<0.05). Younger adults more often (P<0.05) declared that they had eye pain or hypersensitivity to light (photophobia). The prevalence of vision deterioration in the last 30 days was almost 2 times higher among respondents with higher education compared to those with primary or vocational education (P=0.003). The prevalence of bloodshot eyes/red eyes was the highest among those with primary education (20.8%), and 2 times higher when compared to those with vocational training (7.0%) or vocational education (9.7%; P=0.01). The prevalence of hypersensitivity to light (photophobia) was higher among those who were not married (13.6% vs 7.5%; P=0.001). Unemployed people more often declared that they had burning and stinging eyes in the last 30 days (26.5% vs 18.4%; P=0.002) or excessive tearing (18.2% vs 13.0%; P=0.02). Those with low economic status compared to those with high or moderate economic status more often declared the presence of eye pain in the last 30 days (P=0.04). In general, respondents with chronic diseases more often declared the presence of 7 different eye symptoms and vision problems when compared to healthy individuals (P<0.05). Those who wore spectacles/contact lenses more often declared that they had vision deterioration, bloodshot eyes/red eyes, or dry eyes (P<0.05). There were no significant differences in the prevalence of 8 analyzed eye symptoms by place of residence or the number of household members (P>0.05). Details are presented in Table 3.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PRESENCE OF AT LEAST 1 OPHTHALMIC SYMPTOM IN THE LEAST 30 DAYS:

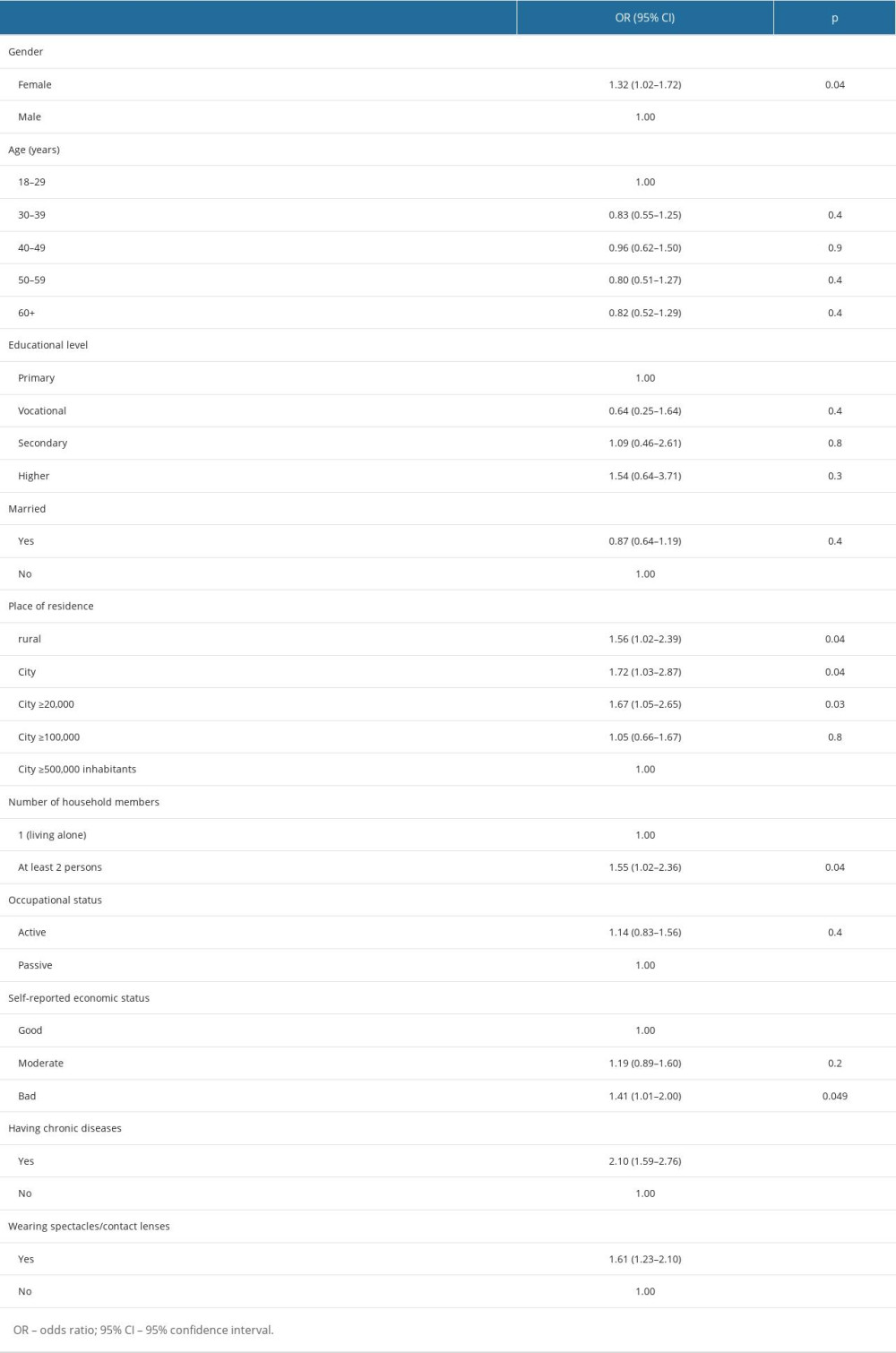

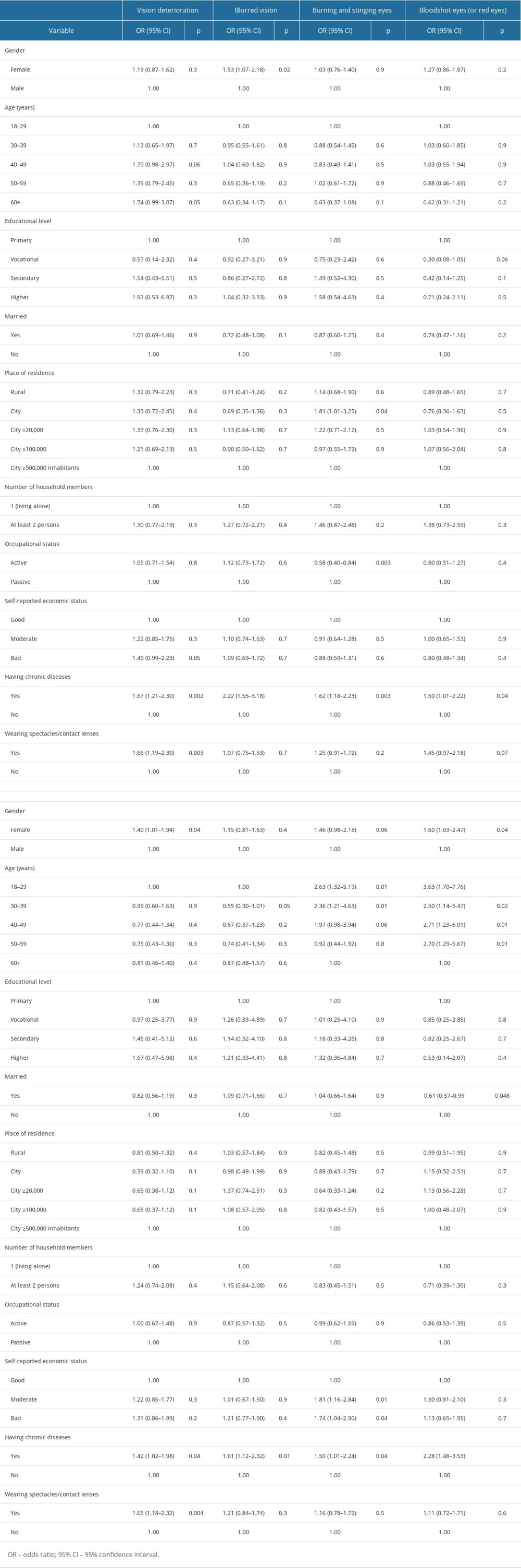

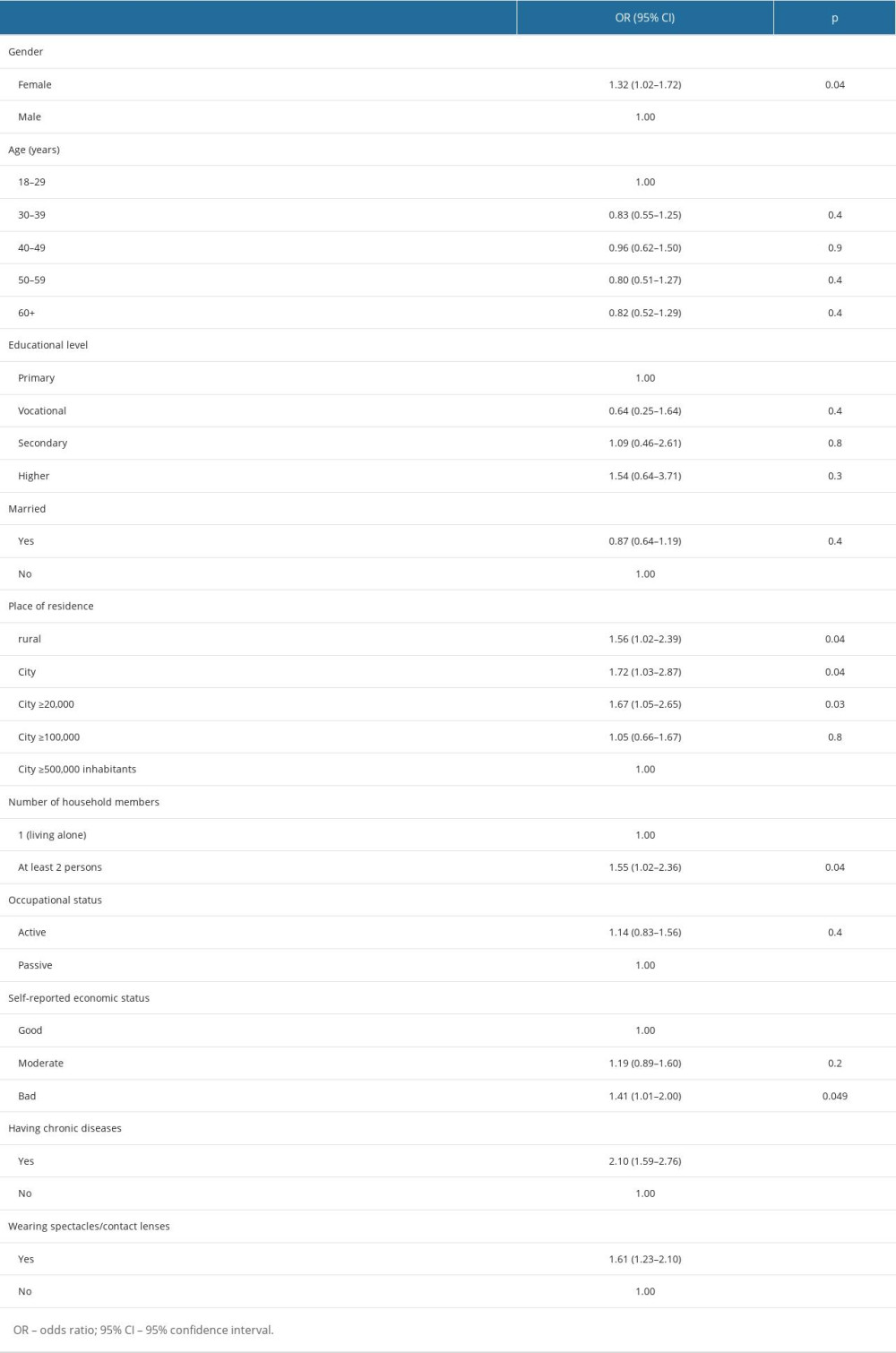

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, females (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.02–1.72, P=0.04), those who lived in rural area or cities below 100 000 inhabitants (P<0.05), those who lived with at least 1 other person (OR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.02–2.36, P=0.04), those with low economic status (OR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.01–2.00, P=0.049), respondents with chronic diseases (OR: 2.10, 95% CI: 1.59–2.76, P<0.001), and those wearing spectacles/contact lenses (OR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.23–2.10, P<0.001) were more likely to have ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days (Table 4).

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PRESENCE OF OPHTHALMIC SYMPTOMS IN THE LEAST 30 DAYS:

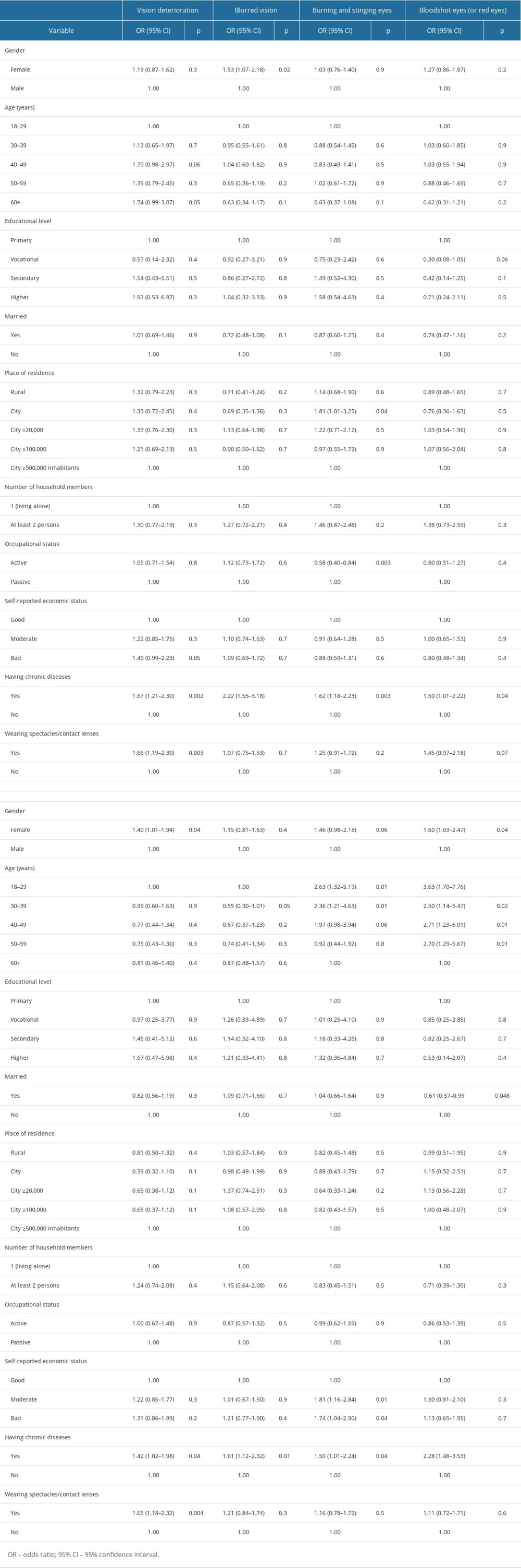

The presence of chronic diseases was the most important factor associated with the presence of all 8 eye symptoms and vision problems (Table 5) analyzed in this study (P<0.05). Females were more likely to have blurred vision (OR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.07–2.18, P=0.02), dry eyes (OR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.01–1.94, P=0.04), and hypersensitivity to light (photophobia) (OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.03–2.47, P=0.04). The risk of having eye pain or hypersensitivity to light (photophobia) decreased with age (P<0.05). Married respondents were less likely to have hypersensitivity to light (photophobia) (OR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.37–0.99, P=0.048). Respondents who lived in the smallest cities (below 20 000 residents) were more likely to have burning and stinging eyes (OR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.01–3.25, P=0.04), compared to those who lived in the largest cities). Employed people were less likely to have burning and stinging eyes (OR: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.40–0.84, P=0.003). Respondents with moderate or low economic status were more likely to have eye pain than those with high economic status (P<0.05). Respondents who wear spectacles/contact lenses were more likely to have vision deterioration (OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.19–2.30, P=0.003), or dry eyes (OR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.18–2.32, P=0.004). There was no association of educational level or housing conditions with the presence of the 8 ophthalmic symptoms analyzed in this study (P>0.05).

Discussion

This study produced the most up-to-date data on the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in a nationwide sample of adults in Poland. Over one-half of adults in Poland had at least 1 ophthalmic symptom in the last 30 days (November–December 2022). Burning and stinging eyes, vision deterioration, and dry eyes were the most common ophthalmic symptoms declared by adults in Poland. Out of 10 different factors analyzed in this study, female gender, living in rural areas or small cities (below 100 000 inhabitants), living with at least 1 other person, having low economic status, having chronic diseases, and wearing spectacles/contact lenses were significantly associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days.

Saldanha et al reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, individuals with moderately dry eyes experienced increased eye strain [18]. Moreover, individuals with severe dry eye had reduced access to treatment, resulting in limited professional activity [18]. Findings from the meta-analysis carried out by Watcharapalakorn et al showed that the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated myopic progression, especially among children and adolescents [17]. Usgaonkar et al reported a significant increase in digital activities on multiple digital devices among adults in India, which led to ocular symptoms like watering eyes, itching eyes, and pain behind the eyes [29].

This study was carried out over 2 years after the COVID-19 pandemic onset in Poland [30]. Respondents were asked about the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days (November–December 2022), and over 57% of them reported at least 1 ophthalmic symptom. As this is the first representative study on the presence of ophthalmic symptoms, direct comparison with previously published data is difficult. However, findings from this study are in line with the data from the US [18] and India [17] and confirm that the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on eye health and the health status of the population.

The most common ophthalmic symptoms reported by the respondents were burning/stinging eyes and dry eyes. Burning eyes manifested as a stinging or irritating sensation may be associated with conjunctivitis, ocular allergy [31], or computer vision syndrome [15]. Dry eye syndrome is one of the most common eye conditions, with the global prevalence estimated at 11.59% [32]. In this study, 18.9% of respondents declared they had dry eye symptoms in the last 30 days. This study was carried out in the fall/winter season (November–December 2022), so environmental factors, including indoor factors like temperature, humidity, and air quality, may evoke ophthalmic symptoms [10,13]. Moreover, exposure to air pollution caused by traffic and heating season (burning coal) can also cause eye irritation and evoke ophthalmic symptoms [11]. Moreover, low temperature, limited sunlight, and reduced outdoor time in November and December may also lead to habits that increase the risk of ophthalmic symptoms, like increased screen time (eg, watching TV or streaming platforms) and computer use (risk of CVS) [33]. In this study, over 20% of respondents declared vision deterioration in the last 30 days. These symptoms may result from exposure to environmental factors (eg, limited lighting) as well as eye strain (eg, caused by an increase in screen time). However, this finding requires further investigation.

Out of 10 different factors analyzed in this study, 6 were significantly associated with the presence of at least 1 ophthalmic symptom in the least 30 days. Females were more likely to declare the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days. This is in line with the epidemiology of eye conditions, as females are at higher risk of eye diseases (eg, dry eye syndrome due to hormonal changes during their lifetime) [34]. Living in rural areas and small cities (below 100 00 inhabitants) was also associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms. Those who live in rural areas are at higher risk of several environmental factors that can affect eye health, occupational risk factors, and lifestyle factors [35]. Place of residence also affects lifestyle behaviors (like tobacco use), access to healthcare, and individual health behaviors and competencies [36]. Findings from this study suggest that inhabitants of rural areas and small cities should be considered as a target audience for eye health education and preventive programs. We found that low economic status was associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms. In Poland, eye healthcare services are often provided by private medical facilities (eg, eye examinations) [37], so financial barriers to access to eye healthcare may occur. Moreover, economic status is often associated with housing conditions and exposure to environmental factors that can evoke ophthalmic symptoms.

Several chronic diseases, including arterial hypertension, diabetes, and autoimmunological diseases, are well-known factors for eye diseases [38–40]. In this study, the presence of chronic diseases was associated with a higher risk of the presence of ophthalmic symptoms, which is in line with data on the impact of comorbidities on eye conditions and disorders [39,40]. Moreover, respondents who wear spectacles or contact lenses were at higher risk of ophthalmic symptoms. Inappropriate hand hygiene increases the risk of contact lens-related corneal infection [41]. An incorrectly or insufficiently corrected refractive error can also lead to vision problems [42]. Findings from this study suggest that individuals with chronic diseases or wearing spectacles/contact lenses are at higher risk of ophthalmic symptoms, so public health policies should address the health needs of these groups.

This study has practical implications for public health in Poland. This is the first comprehensive epidemiological survey of ophthalmic symptoms in a nationwide sample of adults in Poland. Over one-half of adults in Poland reported the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days, which indicates the high burden of eye conditions in Poland. The most common ophthalmic symptoms were related to lifestyle or environmental factors (dry eyes, burning and stinging eyes), which underlines the need to improve public knowledge of eye health. Moreover, this study suggests that public health actions are needed to promote eye care behaviors that reduce eye symptoms. Eye health should be an important part of the National Health Strategy, as vision is a crucial sense. This study was carried out over 2 years after the COVID-19 pandemic onset, so findings from this study may be used for the development of public health strategies aimed at counteracting the healthcare backlog caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The presence of ophthalmic symptoms and vision problems was self-declared, which is the major limitation of this study. The duration of ophthalmic symptoms was not analyzed (only the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the last 30 days was analyzed). As this was a web-based survey, an eye examination was not carried out. CAWI technique was used, so only Internet users were included, but over 90% of polish households have Internet access [25]. Moreover, the datasets generated in this study were anonymous, so the medical records of individual respondents were not verified. Sociodemographic questions were limited to 9 items, and questions on environmental factors, including exposure to irritants, were not asked. Moreover, screen time (including computer or smartphone) was not assessed, so the correlation between eye symptoms and screen time was unknown.

Conclusions

This study revealed a high prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms among adults in Poland in autumn 2022. Females, those living in rural areas or small cities below 100 000 inhabitants, and individuals with low economic conditions were at higher risk of the presence of ophthalmic symptoms. Public health interventions are needed to increase public knowledge of eye health and eye care behaviors that can reduce ophthalmic symptoms. Emphasis should be paid to preventive and educational activities targeted at individuals with chronic diseases as well as those wearing spectacles or contact lenses.

Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population by the presence of ophthalmic symptoms (n=1076). Table 2. The prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms among adults in Poland (n=1076).

Table 2. The prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms among adults in Poland (n=1076). Table 3. The prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms and vision problems by sociodemographic factors (n=1076).

Table 3. The prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms and vision problems by sociodemographic factors (n=1076). Table 4. Factors associated with the presence of at least one ophthalmic symptom in the least 30 days in a nationwide sample of 1076 adults in Poland.

Table 4. Factors associated with the presence of at least one ophthalmic symptom in the least 30 days in a nationwide sample of 1076 adults in Poland. Table 5. Factors associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the least 30 days in a nationwide sample of 1076 adults in Poland.

Table 5. Factors associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the least 30 days in a nationwide sample of 1076 adults in Poland.

References

1. Enoch J, McDonald L, Jones L, Evaluating whether sight is the most valued sense: JAMA Ophthalmol, 2019; 137(11); 1317-20

2. Assi L, Chamseddine F, Ibrahim P, A global assessment of eye health and quality of life: A systematic review of systematic reviews: JAMA Ophthalmol, 2021; 139(5); 526-41

3. Edward DP, Kaufman LM, Anatomy, development, and physiology of the visual system: Pediatr Clin North Am, 2003; 50(1); 1-23

4. GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study, Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study: Lancet Glob Health, 2021; 9(2); e130-e43

5. World Health Organization: World report on vision, 2019, Geneva, World Health Organization

6. Yang X, Chen H, Zhang T, Global, regional, and national burden of blindness and vision loss due to common eye diseases along with its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019: Aging (Albany NY), 2021; 13(15); 19614-42

7. Stein JD, Khawaja AP, Weizer JS, Glaucoma in adults-screening, diagnosis, and management: A review: JAMA, 2021; 325(2); 164-74

8. Richdale K, Chao C, Hamilton M, Eye care providers’ emerging roles in early detection of diabetes and management of diabetic changes to the ocular surface: A review: BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2020; 8(1); e001094

9. Miller JR, Hanumunthadu D, Inflammatory eye disease: An overview of clinical presentation and management: Clin Med (Lond), 2022; 22(2); 100-3

10. Wolkoff P, External eye symptoms in indoor environments: Indoor Air, 2017; 27(2); 246-60

11. Jung SJ, Mehta JS, Tong L, Effects of environment pollution on the ocular surface: Ocul Surf, 2018; 16(2); 198-205

12. Terauchi R, Ogawa S, Sotozono A, Seasonal fluctuation in intraocular pressure and its associated factors in primary open-angle glaucoma: Eye (Lond), 2021; 35(12); 3325-32

13. Huang A, Janecki J, Galor A, Association of the indoor environment with dry eye metrics: JAMA Ophthalmol, 2020; 138(8); 867-74

14. Wang MTM, Muntz A, Mamidi B, Modifiable lifestyle risk factors for dry eye disease: Cont Lens Anterior Eye, 2021; 44(6); 101409

15. Dostálová N, Vrubel M, Kachlík P, Computer vision syndrome – symptoms and prevention: Cas Lek Cesk, 2021; 160(2–3); 88-92

16. Li M, Xu L, Tan CS, Systematic review and meta-analysis on the impact of COVID-19 pandemic-related lifestyle on myopia: Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila), 2022; 11(5); 470-80

17. Watcharapalakorn A, Poyomtip T, Tawonkasiwattanakun P, Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak and associated public health measures increase the progression of myopia among children and adolescents: Evidence synthesis: Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, 2022; 42(4); 744-52

18. Saldanha IJ, Petris R, Makara M, Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eye strain and dry eye symptoms: Ocul Surf, 2021; 22; 38-46

19. Neti N, Prabhasawat P, Chirapapaisan C, Provocation of dry eye disease symptoms during COVID-19 lockdown: Sci Rep, 2021; 11(1); 24434

20. Anantharaman D, Radhakrishnan A, Anantharaman V, Subjective dry eye symptoms in pregnant women – a SPEED survey: J Pregnancy, 2023; 2023; 3421269

21. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Poland [Internet] January, 2023 Available from: https://www.oecd.org/poland/

22. The Nationwide Research Panel Ariadna: About us [Internet] January, 2023 Available from: https://panelariadna.com/

23. Ostrowska A, Jankowski M, Pinkas J, Public support for car smoking bans in Poland: A 2022 national cross-sectional survey: BMJ Open, 2022; 12(10); e066247

24. Żarnowski A, Jankowski M, Gujski M, Use of mobile apps and wearables to monitor diet, weight, and physical activity: A cross-sectional survey of adults in Poland: Med Sci Monit, 2022; 28; e937948

25. : Statistics Poland. Demographic Yearbook of Poland 2022 [Internet] December 22, 2022 Available from: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbooks/demographic-yearbook-of-poland-2022,3,16.html

26. Fricke TR, Tahhan N, Resnikoff S, Global prevalence of presbyopia and vision impairment from uncorrected presbyopia: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling: Ophthalmology, 2018; 125(10); 1492-99

27. GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study, Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study: Lancet Glob Health, 2021; 9(2); e144-e60

28. Varma R, Vajaranant TS, Burkemper B, Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the United States: Demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050: JAMA Ophthalmol, 2016; 134(7); 802-9

29. Usgaonkar U, Shet Parkar SR, Shetty A, Impact of the use of digital devices on eyes during the lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic: Indian J Ophthalmol, 2021; 69(7); 1901-6

30. Raciborski F, Pinkas J, Jankowski M, Dynamics of the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Poland: An epidemiological analysis of the first 2 months of the epidemic: Pol Arch Intern Med, 2020; 130(7–8); 615-21

31. Leonardi A, Silva D, Perez Formigo D, Management of ocular allergy: Allergy, 2019; 74(9); 1611-30

32. Papas EB, The global prevalence of dry eye disease: A Bayesian view: Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, 2021; 41(6); 1254-66

33. Lissak G, Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study: Environ Res, 2018; 164; 149-57

34. Clayton JA, Davis AF, Sex/gender disparities and women’s eye health: Curr Eye Res, 2015; 40(2); 102-9

35. Saliba AJ, Impact of rurality on optical health: Review of the literature and relevant Australian Bureau of Statistics data: Rural Remote Health, 2008; 8(4); 1056

36. Rolfe S, Garnham L, Godwin J, Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: Developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework: BMC Public Health, 2020; 20(1); 1138

37. Kamińska A, Pinkas J, Jankowski M, Factors associated with the frequency of eye examinations among adults in Poland – a nationwide cross-sectional survey, December 2022: Ann Agric Environ Med, 2023; 2023; 159152

38. Gale MJ, Scruggs BA, Flaxel CJ, Diabetic eye disease: A review of screening and management recommendations: Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2021; 49(2); 128-45

39. Dziedziak J, Zaleska-Żmijewska A, Szaflik JP, Impact of arterial hypertension on the eye: A review of the pathogenesis, diagnostic methods, and treatment of hypertensive retinopathy: Med Sci Monit, 2022; 28; e935135

40. Bustamante-Arias A, Ruiz Lozano RE, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Dry eye disease, a prominent manifestation of systemic autoimmune disorders: Eur J Ophthalmol, 2022; 32(6); 3142-62

41. Fleiszig SMJ, Kroken AR, Nieto V, Contact lens-related corneal infection: Intrinsic resistance and its compromise: Prog Retin Eye Res, 2020; 76; 100804

42. Lou L, Yao C, Jin Y, Global patterns in health burden of uncorrected refractive error: Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2016; 57(14); 6271-77

Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population by the presence of ophthalmic symptoms (n=1076).

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population by the presence of ophthalmic symptoms (n=1076). Table 2. The prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms among adults in Poland (n=1076).

Table 2. The prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms among adults in Poland (n=1076). Table 3. The prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms and vision problems by sociodemographic factors (n=1076).

Table 3. The prevalence of ophthalmic symptoms and vision problems by sociodemographic factors (n=1076). Table 4. Factors associated with the presence of at least one ophthalmic symptom in the least 30 days in a nationwide sample of 1076 adults in Poland.

Table 4. Factors associated with the presence of at least one ophthalmic symptom in the least 30 days in a nationwide sample of 1076 adults in Poland. Table 5. Factors associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the least 30 days in a nationwide sample of 1076 adults in Poland.

Table 5. Factors associated with the presence of ophthalmic symptoms in the least 30 days in a nationwide sample of 1076 adults in Poland. In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Outcomes between Single-Level and Double-Level Corpectomy in Thoracolumbar Reconstruction: A ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943797

21 Mar 2024 : Meta-Analysis

Economic Evaluation of COVID-19 Screening Tests and Surveillance Strategies in Low-Income, Middle-Income, a...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943863

10 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Predicting Acute Cardiovascular Complications in COVID-19: Insights from a Specialized Cardiac Referral Dep...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942612

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Enhanced Surgical Outcomes of Popliteal Cyst Excision: A Retrospective Study Comparing Arthroscopic Debride...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.941102

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952