02 August 2023: Clinical Research

Impact of Alcohol Consumption, Smoking, and Diet on the Severity of Plaque Psoriasis: A Comprehensive Assessment using Clinical Scales and Quality of Life Measures

Piotr Michalski1ABCDEF*, Veronica Palazzo-Michalska1CDE, Anna Michalska-Bańkowska2BDF, Mirosław Bańkowski3F, Beniamin Oskar Grabarek4ACDEDOI: 10.12659/MSM.941255

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e941255

Abstract

BACKGROUND: This study aimed to evaluate the effects of alcohol intake, assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) questionnaire, on the severity of plaque psoriasis using the Body Surface Area (BSA) and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scales, and quality of life using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The diagnosis of psoriasis was made based on the clinical picture. We enrolled 24 patients with psoriasis vulgaris, and the AUDIT test conducted at the time of follow-up indicated a possible risky/harmful pattern of alcohol consumption or alcohol dependence syndrome among the patients (>8 points). The comparison group consisted of 20 psoriatic patients and AUDIT <8 points. The BSA and PASI scales were used to determine the severity of psoriasis, and the DLQI questionnaire assessed patients' quality of life and how they felt during the week preceding the survey.

RESULTS: As the amount and frequency of alcohol consumed increased, the exacerbation of lesions measured according to the PASI and BSA scales was significantly higher (P<0.05), and the quality of life decreased (P<0.05). We noted that inadequate and excessive dietary intake of total protein, total fat, and assimilable carbohydrates were associated with statistically significantly higher values of BSA and PASI scores and, thus, more severe psoriatic lesions (P<0.05).

CONCLUSIONS: An unbalanced diet, alcohol abuse, and smoking negatively affect the course of psoriasis vulgaris, hence the importance of patient education.

Keywords: Alcoholism, Body Surface Area, Psoriasis, Quality of Life, Smoking, Humans, Diet, Alcohol Drinking, Severity of Illness Index, Treatment Outcome

Background

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with an insufficiently understood etiopathogenesis [1,2]. It is estimated that the prevalence of this dermatosis in the Polish population is 2–3%, with a peak incidence at ages 20–30 and 40–50 years [3]. Psoriasis vulgaris is also called plaque psoriasis. The diagnosis is usually made clinically by examining the skin, nails, and scalp [4]. Approximately 1 million people in Poland have psoriasis, but an accurate assessment of the prevalence of psoriasis is not possible, as many patients with mild psoriasis do not see a doctor [5]. The most common clinical form is psoriasis vulgaris, accounting for 90% of cases [6]. It is characterized by the presence of papular lesions on an erythematous base that is covered with silvery-white scales and localized to the scalp (most common), symmetrically on the upright parts of the upper and lower extremities, as well as in the lumbosacral region [6,7]. In contrast, palmoplantar psoriasis mainly involves the palms and soles, is characterized by significant treatment resistance, and significantly reduces the patient’s quality of life (QoL) [6,8].

Conversely, nail psoriasis predisposes to the development of psoriatic arthritis, and skin lesions may merge into larger fragments. This is called plaque psoriasis, a variant typically seen in the elderly [5,7].

The diagnosis is typically made based on the clinical picture. The development of psoriatic lesions at the site of previous mechanical trauma (Köbner’s sign), punctate bleeding at the site of scraping off the last layer of scales (Auspitz’s sign), and the appearance of a shiny surface after scraping off the scales (stearic candle sign) are characteristic of psoriasis [9]. However, these are not specific symptoms [9].

In the event of diagnostic uncertainty, dermoscopy, which reveals a pattern of evenly distributed blood vessels in the form of dots below the stratum corneum and epidermal peeling resembling white scales, may be helpful [10]. When the diagnosis cannot be made based on the clinical picture and dermoscopy, a skin biopsy from the lesion and histopathological confirmation are indicated [6,10].

In treating psoriasis, topical and systemic therapies can be distinguished between conventional and biological treatment [6,11,12]. Topical therapy is the primary form of treatment for mild psoriasis in adults, as assessed by the following indicators: Body Surface Area (BSA; <10%), Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI; <10 points), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI; <10 points) [6,11–13]. According to the literature, about 20–30% of patients have moderate-to-severe psoriasis [6,11,12]. Meeting 1 criterion (ie, BSA ≥10% or PASI ≥10 points, or DLQI ≥10 points) mandates the inclusion of systemic therapy [6,11,12]. The goal of treatment is to try to achieve complete resolution of the lesions, but in many patients, such an outcome is not achievable [6,11,12]. By contrast, patients with post-treatment moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (PASI >10, BSA >10, DLQI >10) who are characterized by poor tolerance or ineffectiveness of prior system treatment at recommended doses for the recommended duration are eligible for biologic therapy [6,11,12].

The PASI scale is a reliable indicator that takes into account the extent and severity of skin lesions. It is characterized by high reproducibility and repeatability. It correlates well with the Self-Administered PASI (SAPASI), the equivalent of the PASI, which is estimated by the patient, [14–18]. Unfortunately, this scale has some limitations [14–18]. First, it assigns an equal value to lesions in areas such as the face, hands, feet, and genitals, and less importance from the patient’s point of view, such as the back [14–18]. Second, this scale does not take into account the impact of the disease on patients’ QoL and the co-occurrence of the patient’s subjective concerns, such as pruritus [14–18]. Third, it is difficult to interpret because the relationship between the PASI score and disease severity is non-linear [14–18]. Fourth, it is also not applicable in evaluating forms of psoriasis other than plaque psoriasis, including erythrodermic or pustular psoriasis [14–18]. Fifth, PASI is a complex, time-consuming scale associated with the risk of calculation error [14–18]. Sixth, its upper limit is only theoretical [14–18]. Despite these drawbacks, the lack of adequate validation and standardization, and numerous attempts to replace it with other scales, PASI is still the best known and most widely used by dermatologists in daily practice and in clinical trials [14–18].

The BSA index, on the other hand, determines the percentage of body surface area occupied by psoriatic lesions in a range from 0 to 100 [18–21]. Studies have shown that the BSA is significantly overestimated, especially in cases of mild disease and inexperience with the scale [18–20]. The BSA should not be used as the only scale to assess the severity of psoriasis, as it does not take into account the morphology of psoriatic lesions [18–20].

The DLQI questionnaire was created in 1994 and consisted of 10 questions aimed to assesses the quality of life of patients with skin lesions and their well-being during the week preceding the survey [22–24]. The scale can be used for patients at least 16 years old and takes about 2 minutes to complete [22–24]. An essential aspect of this questionnaire is that it does not require additional explanations by the doctor and is simple for the patient to complete [22–24].

The influence of genetic and environmental factors has been emphasized in the onset and development of the disease [25,26]. To date, 9 different regions containing genes predisposing to the development of psoriasis have been discovered: PSORS1-9, where the most relevant region is PSORS1, located on chromosome 6p21, which houses genes encoding proteins belonging to the major histocompatibility complex [25,26]. Environmental-modifiable factors that induce psoriasis include noise, air pollution, poor diet, alcohol abuse, nicotinism, and drug abuse [6,27–29]. Physiological stressors involved in the formation of psoriatic lesions include infections, primarily bacterial, and trauma, such as mechanical damage to the epidermis (the so-called Köbner effect) [6,27–29]. Psychological stressors include depression, abnormal social relationships, family conflicts, and professional problems [6,27–29]. However, knowledge of these remains fragmented [6,27–29].

Alcohol can both initiate and exacerbate inflammation by stimulating lymphocyte proliferation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines [30,31]. Based on literature analysis, a significantly higher incidence of alcohol abuse has been observed among psoriasis patients [30,31]. Patients have various psychological and social problems, with particular attention paid to stigma and secondary psychological disorders in the form of depressive and anxiety disorders as consequences of patients’ reactions to chronic skin disease [3,32]. Brenaut et al observed that patients with psoriasis consume alcohol more frequently and in larger amounts than healthy individuals [33]. Wolk et al also observed a statistically significant association between alcohol consumption and the onset of psoriasis in men but not in women. In men, the odds ratio (OR) was 3.4 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.4–8.1) for 5–19 drinks per month and 3.1 (95% CI: 1.4–7.2) for more than 20 drinks per month [34]. This underscores the importance of the prompt assessment of the effect of alcohol consumption on the onset and severity of psoriatic lesions [33,34].

The AUDIT test is a screening test with no absolute diagnostic value. However, it allows for determining the likelihood of alcohol problems, including alcohol dependence, and identifying risky and harmful drinking styles [35–37]. In the comparative studies conducted, the questions were found to be accurate and to have the ability to distinguish between moderate drinkers and those who drink in a harmful manner [35–37]. Its results correspond to the diagnostic criteria contained in the 10th version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Problems (ICD-10) [35–37].

Although no uniform dietary recommendations have been created, there is undoubtedly growing interest in diet therapy for psoriasis [38,39]. The approach of specialists from around the world has changed over the years. Still, it is now recognized that diet plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis in addition to the identified provoking factors [38,39]. There are indications that in patients with psoriasis, the diet used should be low in calories and rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids [40]. Scientific evidence suggests that a diet rich in antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals (selenium, zinc, magnesium, copper, and iron) may help to reduce oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species production [41]. General dietary recommendations for patients with psoriasis include consuming vegetables and fruits, especially those rich in flavonoids and carotenoids, and avoiding alcohol and smoking, red meat, animal fats, and offal [42].

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of alcohol intake, assessed using the AUDIT questionnaire, smoking, and diet on the severity of plaque psoriasis using the BSA and PASI scales and quality of life using the DLQI questionnaire.

Material and Methods

ETHICS:

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Academy of Silesia, Poland (protocol code no. 02/2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participants in the study were informed that the clinical and anthropometric data obtained after pseudo-anonymization, which consists of processing personal data in such a way that it can no longer be attributed to a specific person to whom the data pertains, without the use of additional information. In contrast, this additional information will be stored separately and will be covered by technical and organizational measures that make it possible to transcribe it to an identified or identifiable natural person and would be used only for the preparation of a scientific publication. P.M. and A.M.-B. were responsible for this.

PATIENTS AND THE DIAGNOSIS OF PSORIASIS:

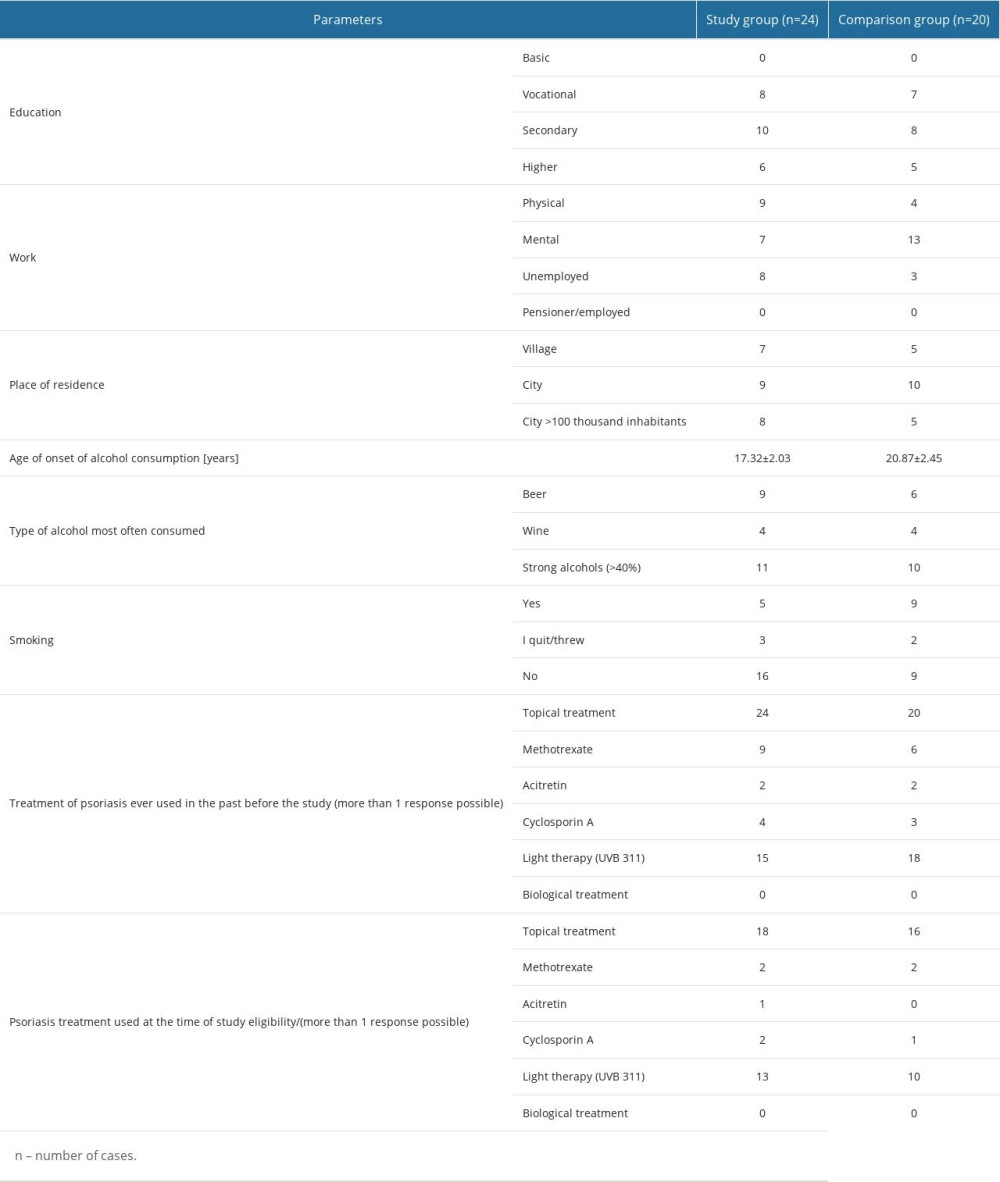

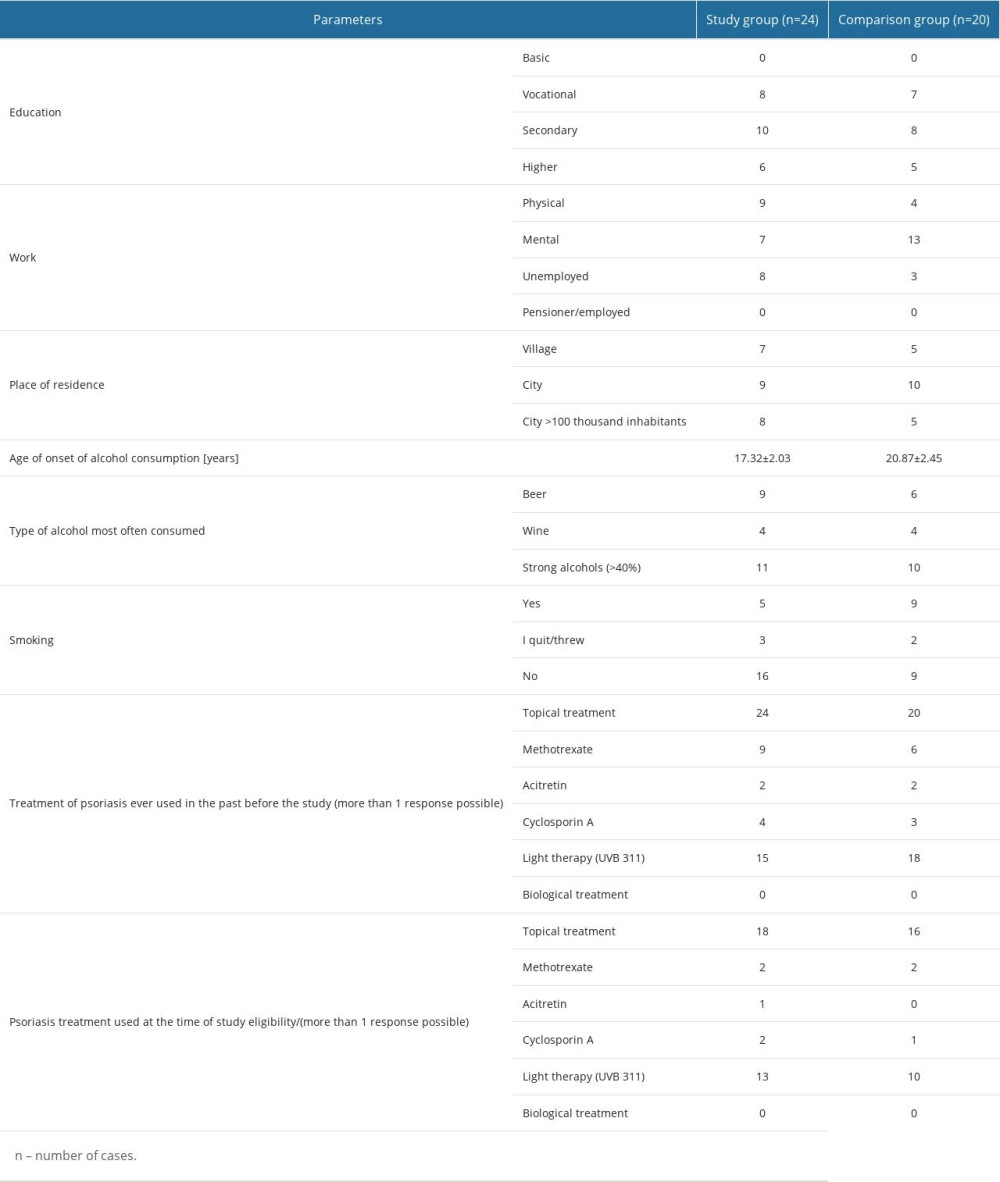

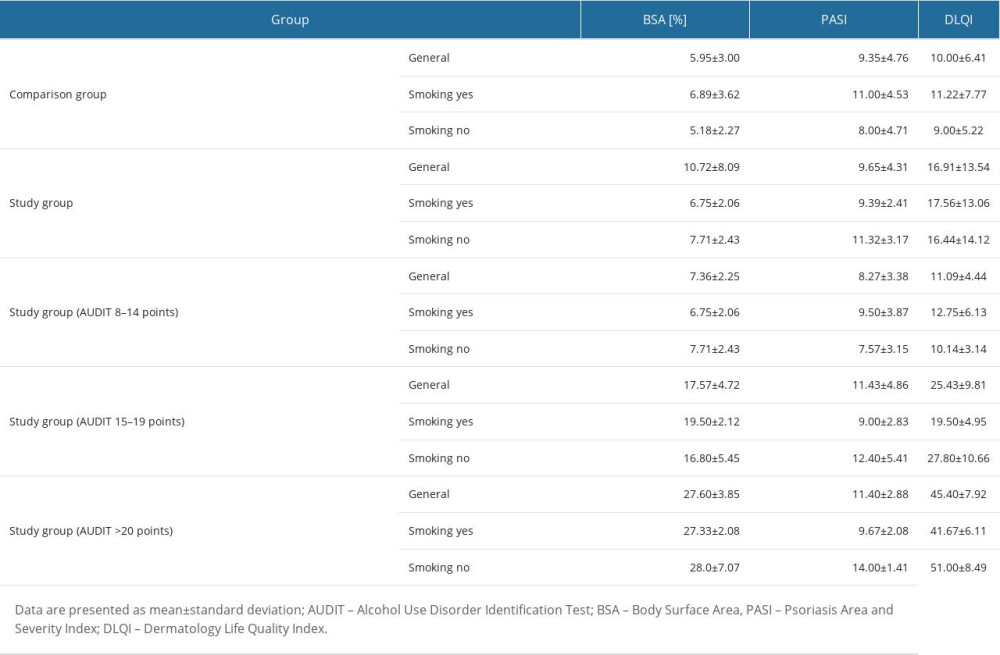

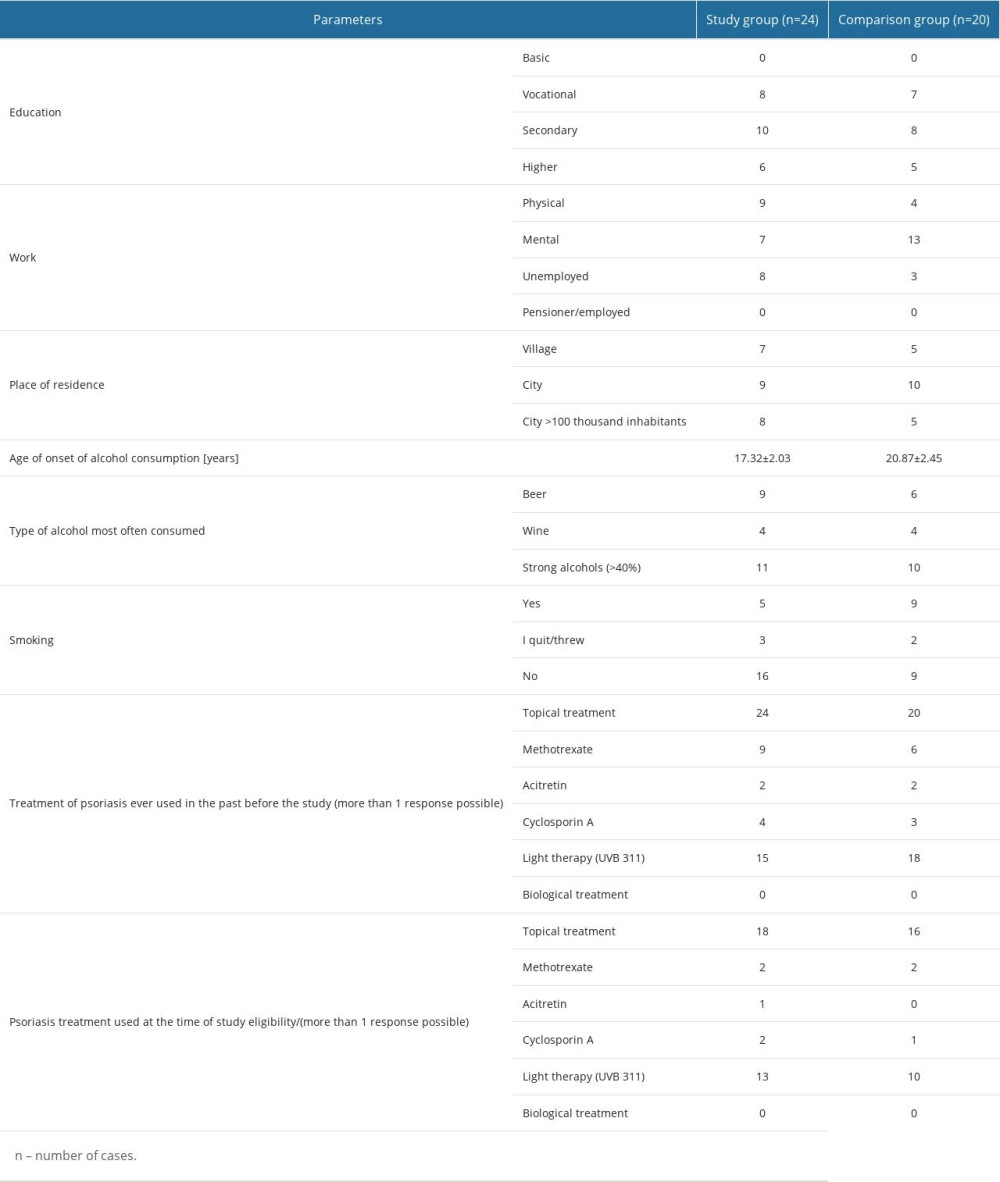

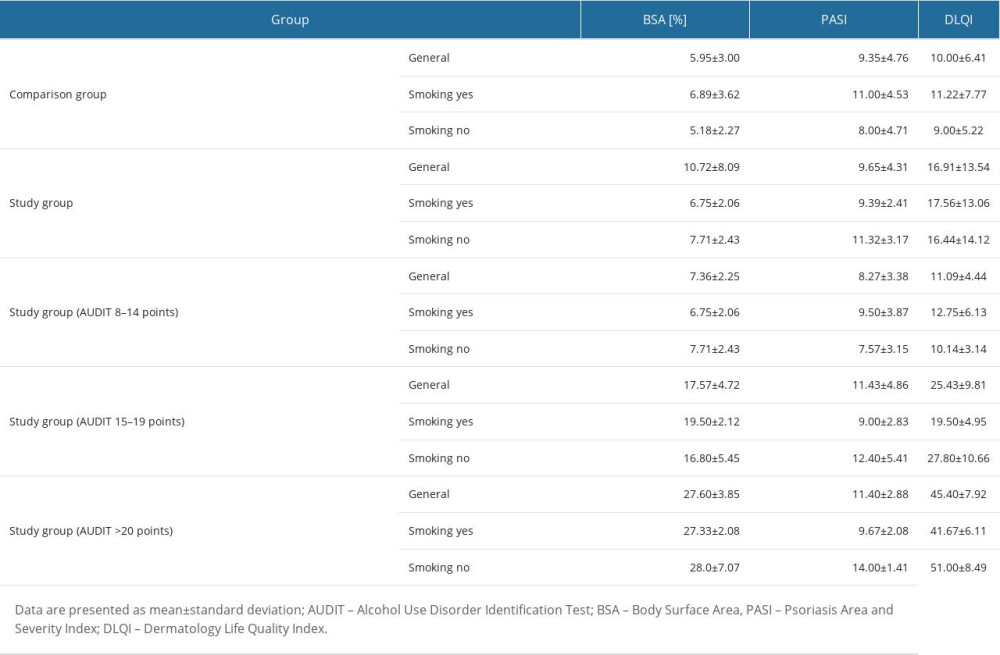

The study initially enrolled 60 patients with moderate psoriasis vulgaris. The diagnosis of psoriasis was made on the basis of the clinical picture. There were no doubtful cases warranting a skin biopsy. However, 44 patients were eventually enrolled and assigned to the study or comparison group depending on their alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT) score. The reasons for excluding 16 participants from the analysis were withdrawal of consent to participate in the study (n=5) or failure to provide all required information in the questionnaires used in the study (n=11). For each patient in the study and comparison group, body mass index (BMI) was assessed, taking a BMI value of <18.5 kg/m2 as underweight, 18.50–24.90 as normal weight, 25.00–29.90 kg/m2 as overweight, and a BMI >30 kg/m2 as obesity. Detailed characteristics of the study and comparison groups are shown in Table 1. Parameters of clinical severity of psoriasis vulgaris and quality of life of patients in the study and comparison groups about alcohol and smoking patterns are shown in Table 2. Patients were asked whether they smoked cigarettes now, in the past, or have never smoked in their lives.

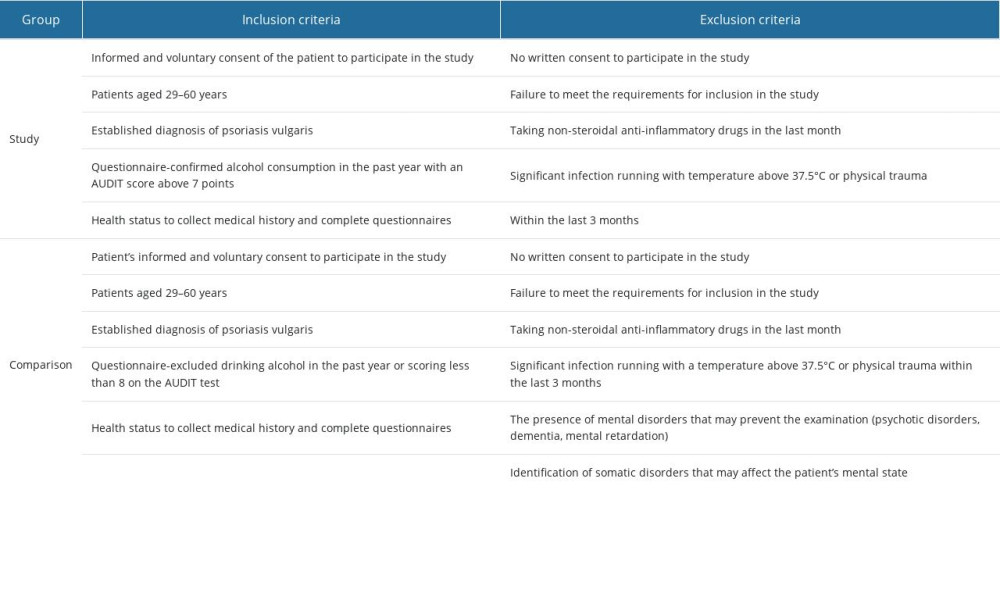

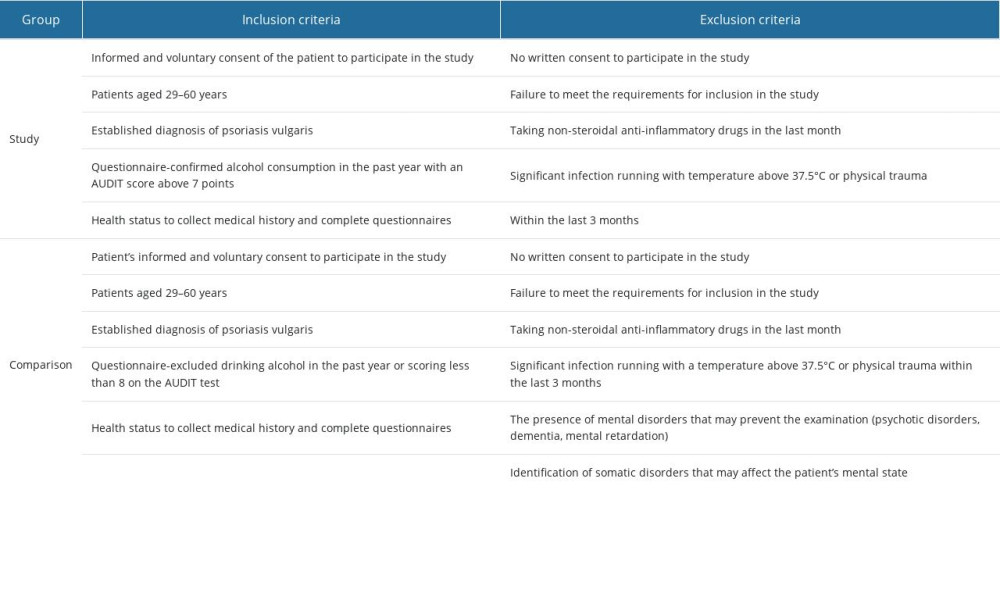

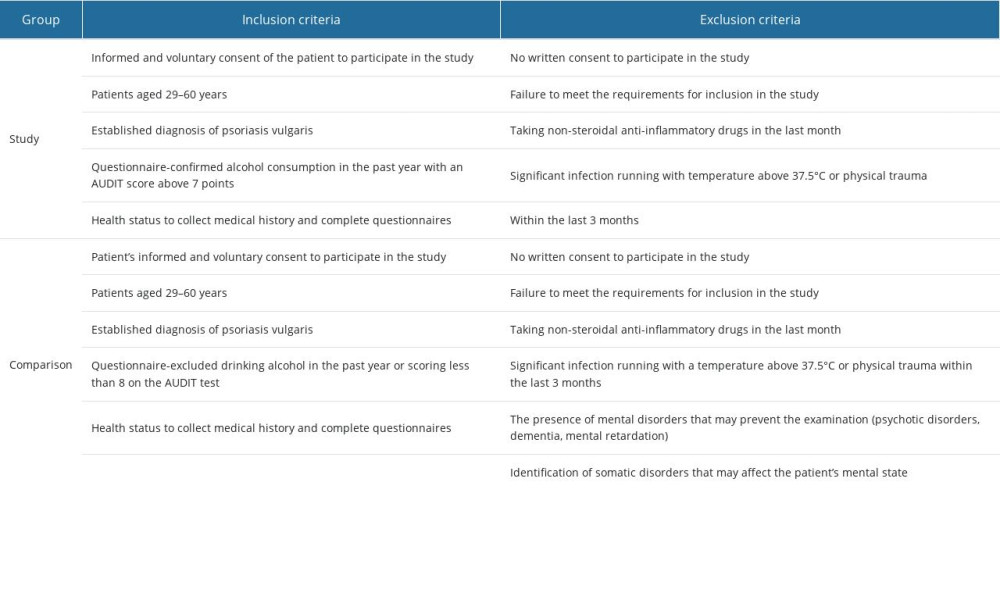

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY GROUP: We enrolled 24 patients (4 women, 20 men; 51.43±3.53 years) with a clinically confirmed diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris (disease duration: 12.7±7.2 years; the number of disease exacerbations requiring hospitalization/year: 1.1±0.4) and a comorbid history of alcohol consumption in the last 12 months preceding study eligibility. The AUDIT test conducted at the time of follow-up indicated a possible risky/harmful pattern of alcohol consumption or alcohol dependence syndrome among the patients, which became the basis for distinguishing the 3 subgroups. The first subgroup consisted of patients who scored 8–14 on the AUDIT test (n=11, 1 woman and 10 men); the second subgroup consisted of patients who scored 15–19 on the AUDIT test (n=8, including 3 women and 5 men); and the third subgroup consisted of patients who scored 20 or more on the AUDIT test (n=5 men). All patients enrolled in the study group met all inclusion criteria, as shown in Table 3.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE COMPARISON GROUP: The comparison group consisted of 20 patients (11 women, 9 men) with a confirmed clinical diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris (disease duration: 14.2±10.79 years; the number of disease exacerbations requiring hospitalization/year: 0.81±0.12) unencumbered by a screening AUDIT score indicating possible alcohol problems (score less than 8 at the start of follow-up). All patients enrolled in the comparison group met all inclusion criteria, as shown in Table 3.

ALCOHOL USE DISORDER IDENTIFICATION TEST (AUDIT) QUESTIONNAIRE:

This test consists of 10 questions on the specific characteristics of alcoholic beverage use and performance. The first 3 questions provide information on the amount and frequency of alcohol drinking. Questions 4 through 6 focus on the symptoms of addiction, and questions 7 through 10 are related to problems caused by alcohol, including mental changes. Interpretation of the results obtained was as follows:

All patients with AUDIT test scores above 7 were referred for an appointment with an addiction specialist to diagnose a possible alcohol problem further. Based on the data obtained, all patients referred for further diagnosis and treatment took advantage of this opportunity.

BODY SURFACE AREA (BSA) SCALE:

The BSA scale allows determining the percentage of the area of skin affected. The premise of this scale is to assign each of the following locations: head and neck, right upper limb, left upper limb, chest, abdomen, upper back, lower back, right thigh, left thigh, right shank, and left shank 9% of the total body surface area, while 1% is the area of the perineum. Another way to determine the percentage of body surface area occupied is to assume that the area of the patient’s hand, including the fingers, corresponds to 1% of the total skin surface.

PSORIASIS AREA AND SEVERITY INDEX (PASI) SCALE:

The PASI scale allows the determination of erythema, lesion thickness, and scale build-up on a 4-point scale, where 0 indicates no lesions and 4 corresponds to severe lesions. It is also possible to determine on a 6-point scale the occupied body surface in 4 localizations: head, trunk, upper extremities, and lower extremities, with 0 points corresponding to 0–10% of the occupied body surface and 6 points indicating 90–100%. A maximum of 72 points can be obtained.

DERMATOLOGY LIFE QUALITY INDEX (DLQI) QUESTIONNAIRE:

DLQI consists of 10 single-choice questions. Each answer to an inquiry was assigned an appropriate number of points on a 4-point scale, where 0 has no effect on quality of life (QoL), 1 has a slight effect, 2 has a large effect, and 3 has a very large effect. A maximum of 30 points can be obtained. The higher the score, the greater the degree to which the patient’s QoL is impaired.

DLQI score:

DIET OF THE PSORIATIC PATIENTS:

A questionnaire survey of product and food intake was conducted with the study patients based on 24-hour dietary interviews, according to the recommendations of the Committee on Human Nutrition Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAS) [43]. The interviews were analyzed for nutritional value using the computer program Diet 5.0, based on the “Tables of Composition and Nutritional Value” [44]. Based on a 24-hour interview, the energy value and average content of essential nutrients in the diets of the studied patients were calculated. The obtained values were compared to the applicable norms of estimated energy requirements (EER), estimated average requirements (EAR), or adequate intake (AI), and the percentage of subjects with sufficient and insufficient information of the studied components were calculated, as well as the percentage of energy derived from proteins, fats, and carbohydrates in the diets.

EAR is the average estimated intake to meet the needs of 50% of healthy individuals. In turn, EER is defined as the average dietary energy intake that is predicted to maintain energy balance in healthy individuals of normal weight at a specified age, sex, weight, height, and level of physical activity consistent with good health. AI is the average nutrient level consumed daily by a specific healthy population that is assumed to be adequate for the population’s needs.

The energy and nutrient standards for patients with moderate psoriasis vulgaris are shown in Table 4.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Statistical analysis was performed using STAT Plus software (AnalystSoft, Brandon, FL33511, USA), with a statistical significance threshold (

SAMPLE SIZE ANALYSIS: Assuming that in Poland, about 12 million people have psoriasis, and moderate psoriasis affects about 10%, taking a margin of error of 4.1.4% and 95% confidence level, the minimum number of subjects that should be included in the study is 44 patients [45].

Results

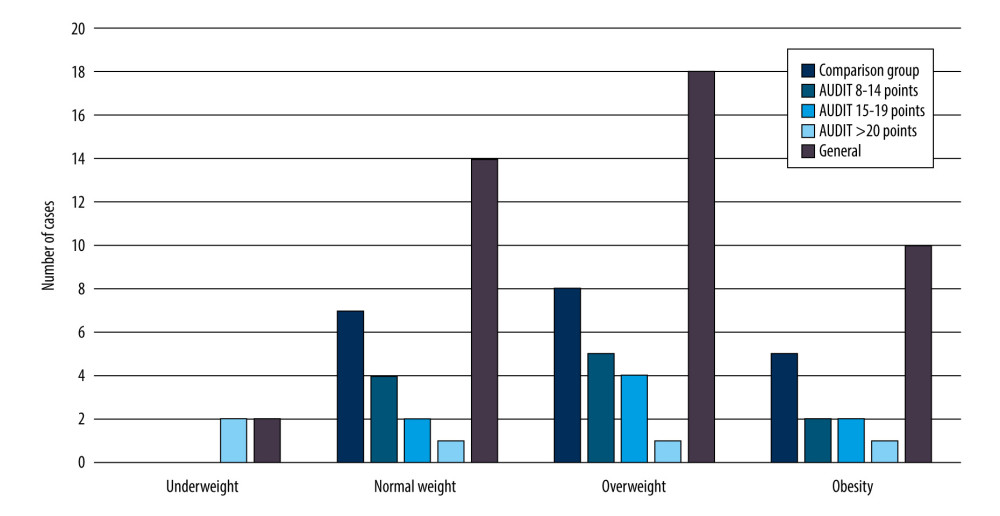

ANALYSIS OF BMI DISTRIBUTION IN THE STUDY AND COMPARISON GROUPS:

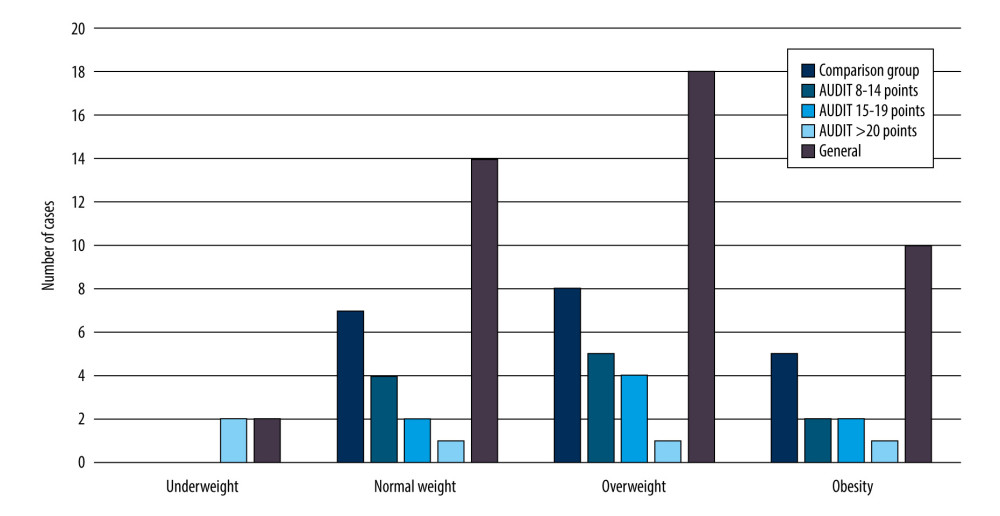

Figure 1 shows the number of patients overall and with the AUDIT questionnaire scores according to their BMI scores. Underweight was observed in only 2 patients who scored at least 20 on the AUDIT test, while normal weight was recorded in 14 patients, overweight in 18 patients, and obesity in 10 patients. In the comparison group, normal weight was recorded in 7 patients, overweight in 8 patients, and obesity in 5 patients. By contrast, in the group of patients who scored between 8 and 14 on the AUDIT test, 4 patients were normal weight, 5 patients were overweight, and 2 patients were obese. Among patients whose AUDIT test scores were between 15 and 19 points, normal weight was noted in 2 patients, overweight in 4, and obesity in 2. By contrast, among patients whose AUDIT test score was 20 or more, normal weight, overweight, and obesity were found in 1 patient each.

ASSESSMENT OF THE SEVERITY OF PSORIATIC LESIONS IN PATIENTS IN THE STUDY AND COMPARISON GROUPS BASED ON THE BSA SCALE:

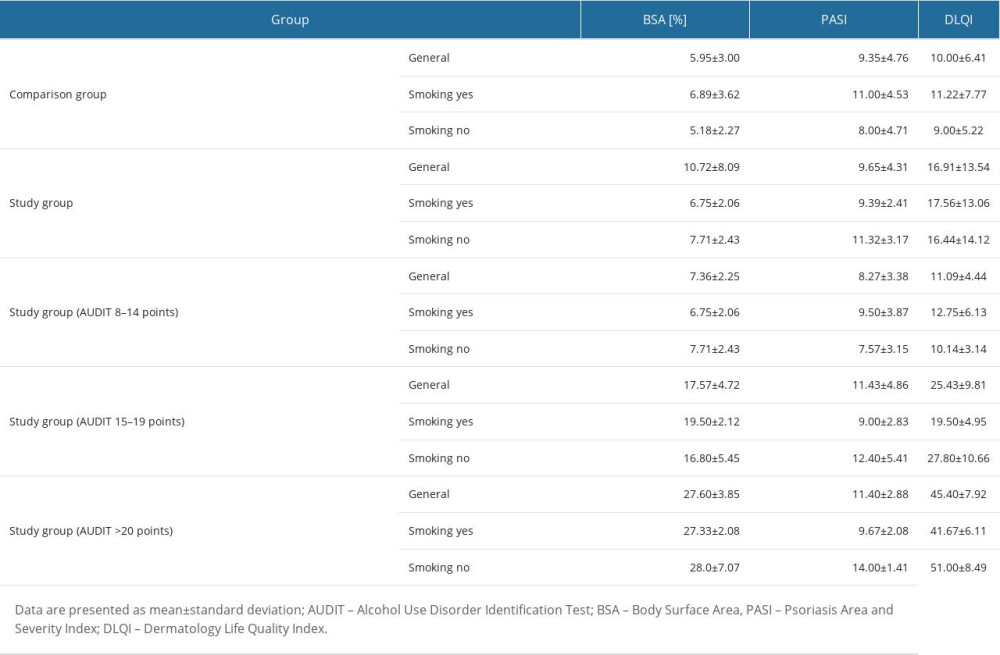

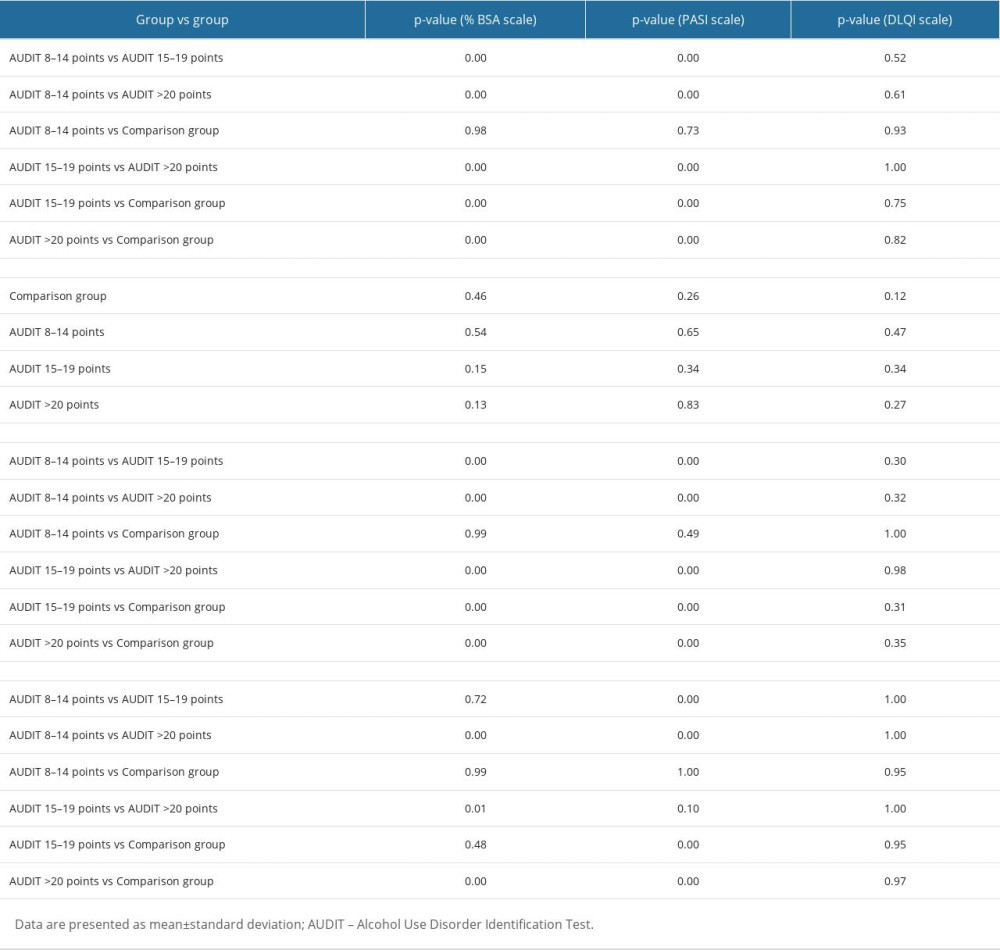

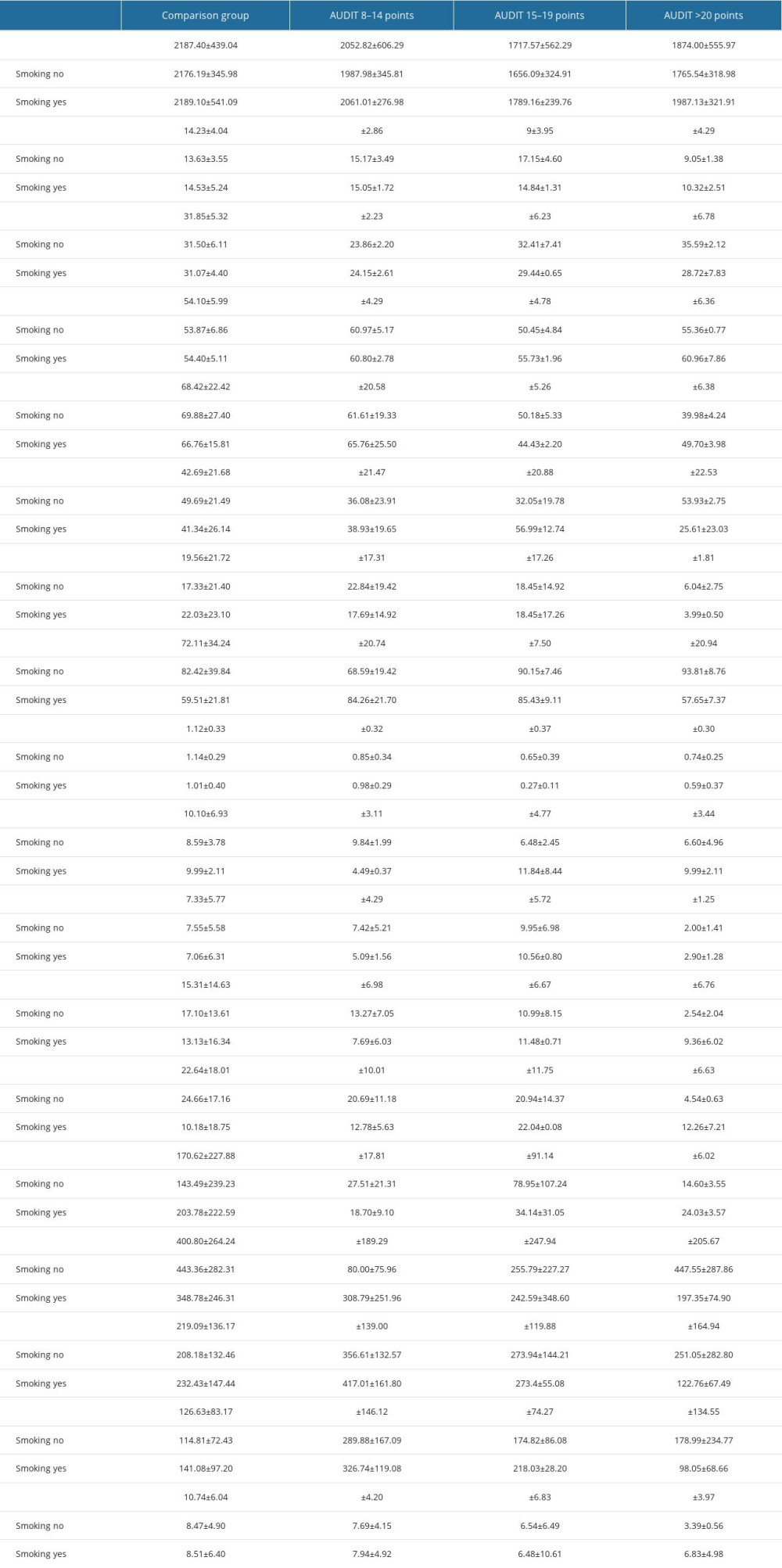

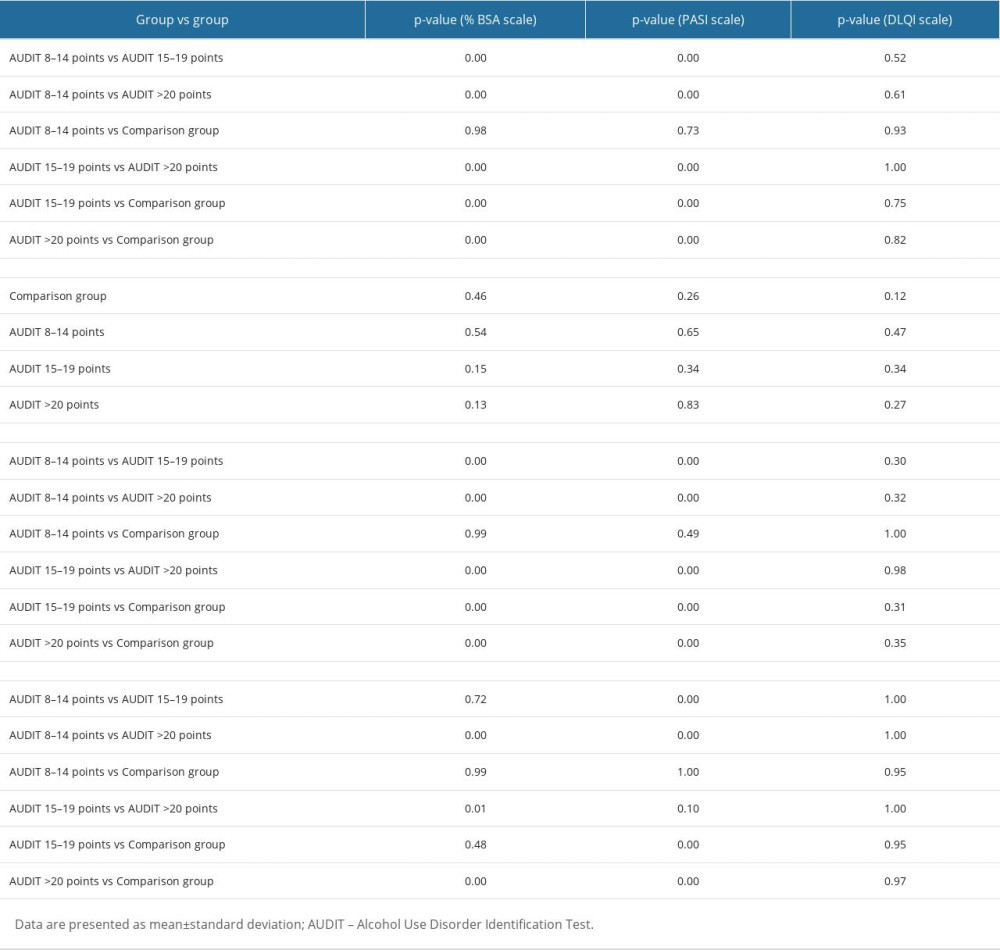

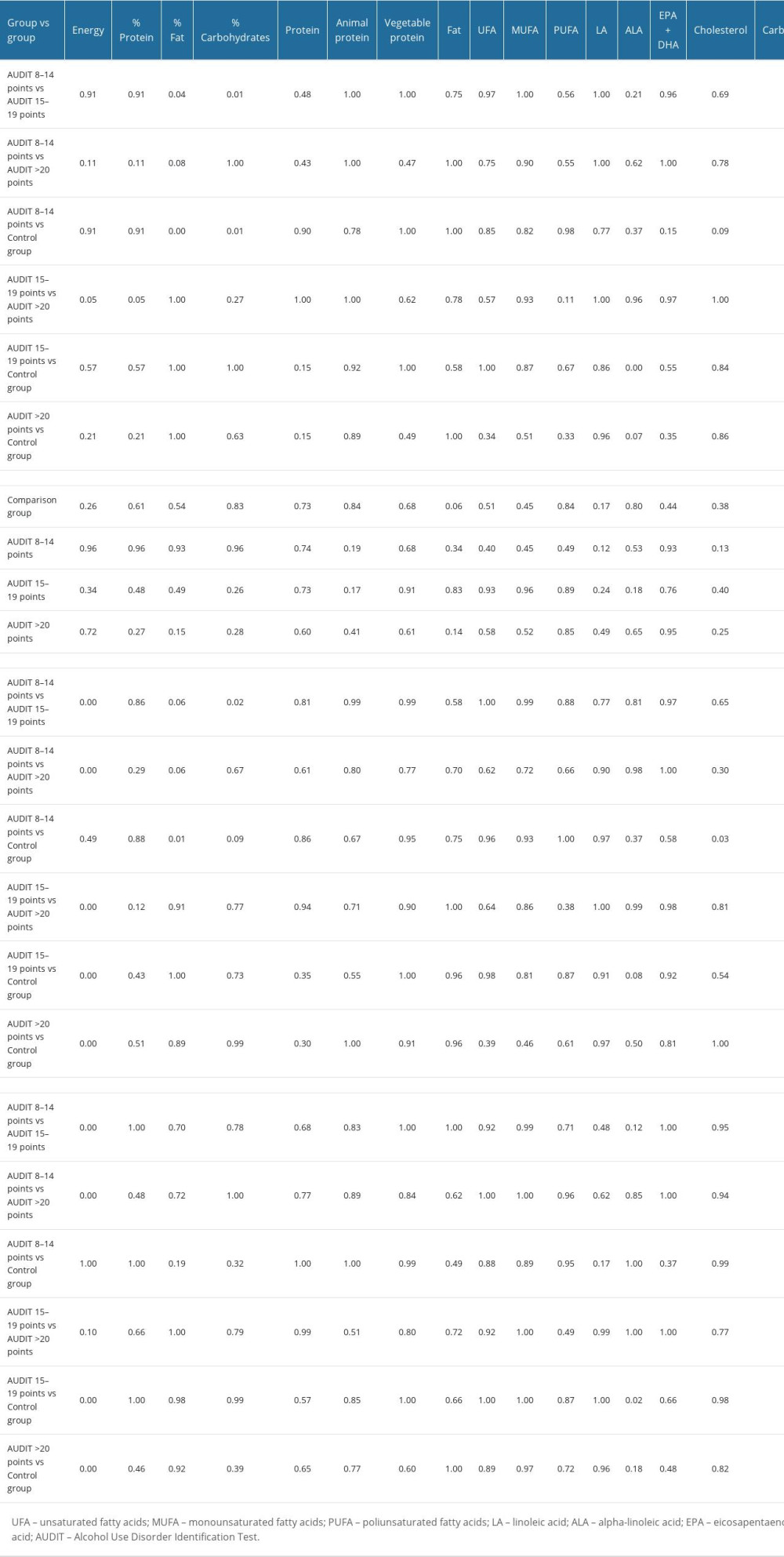

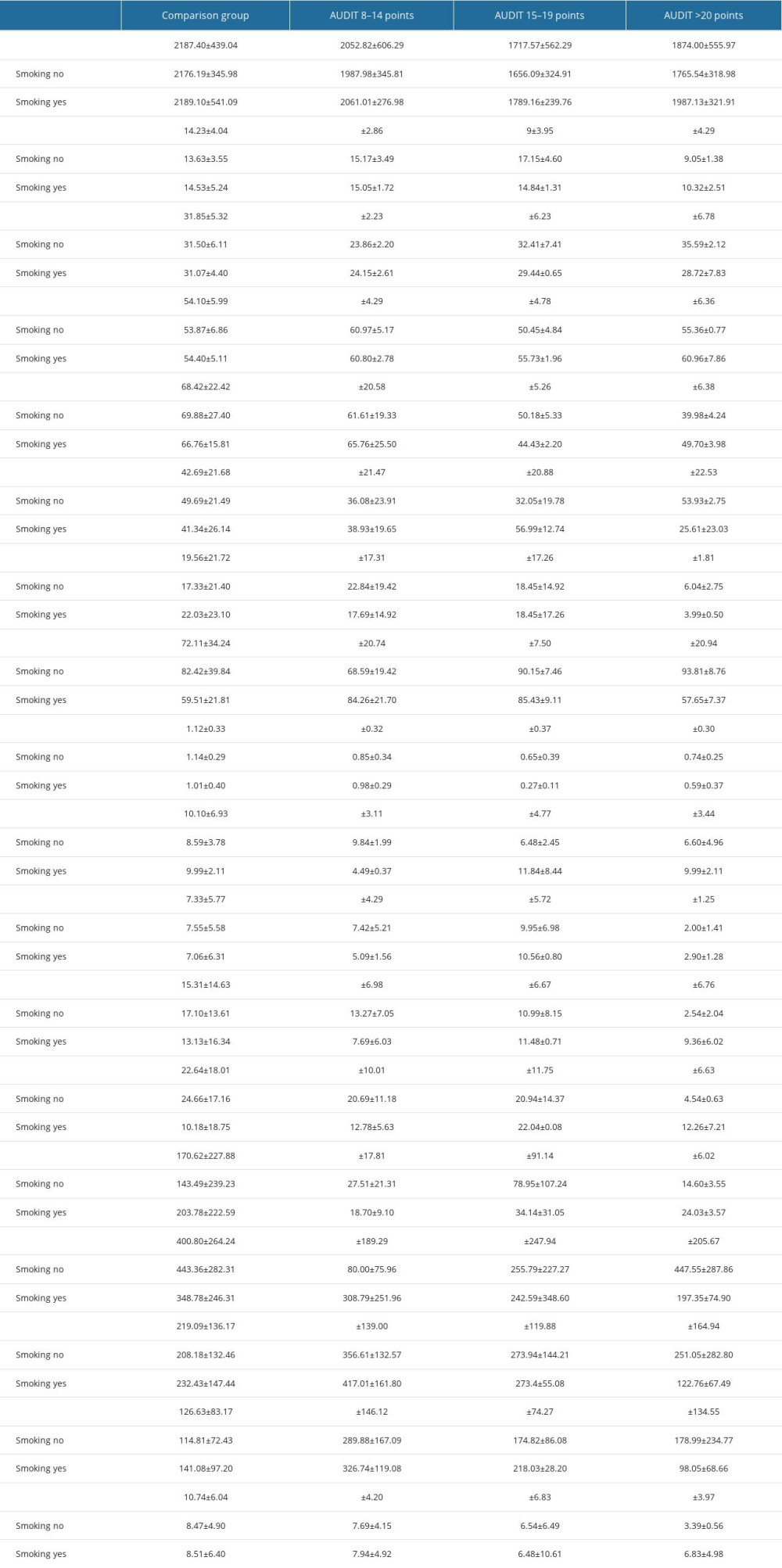

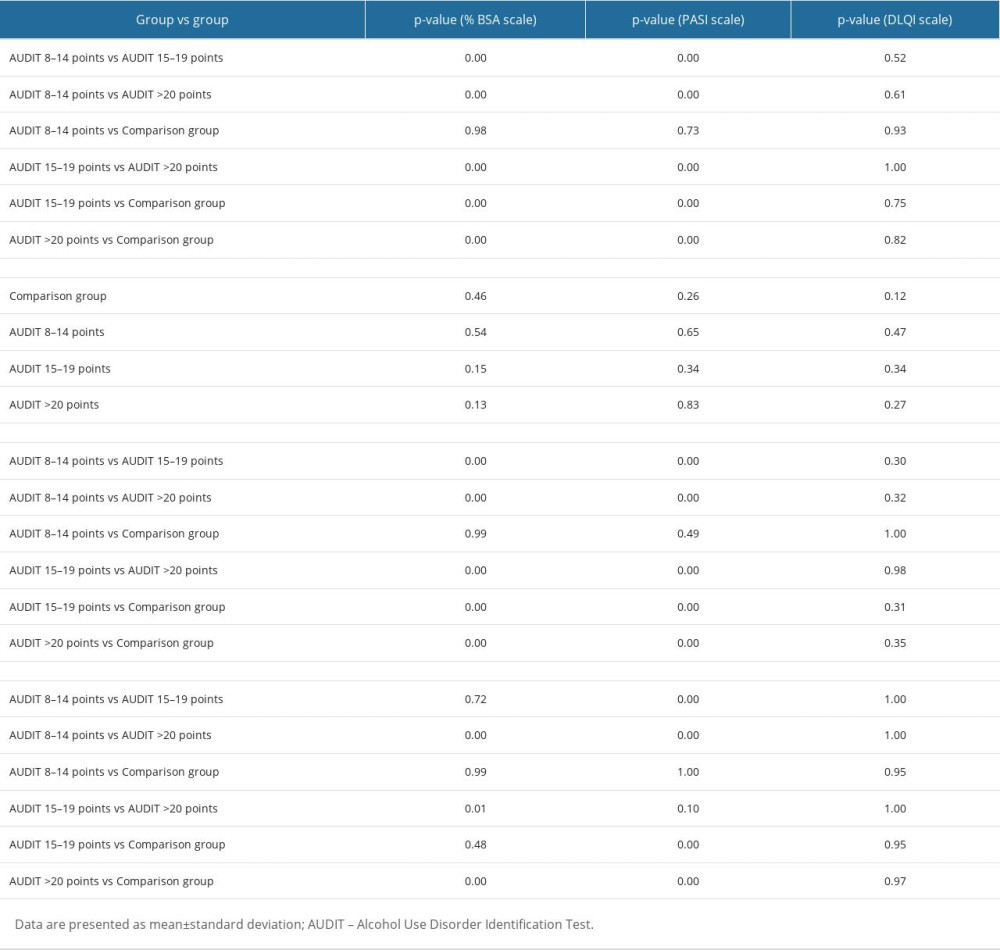

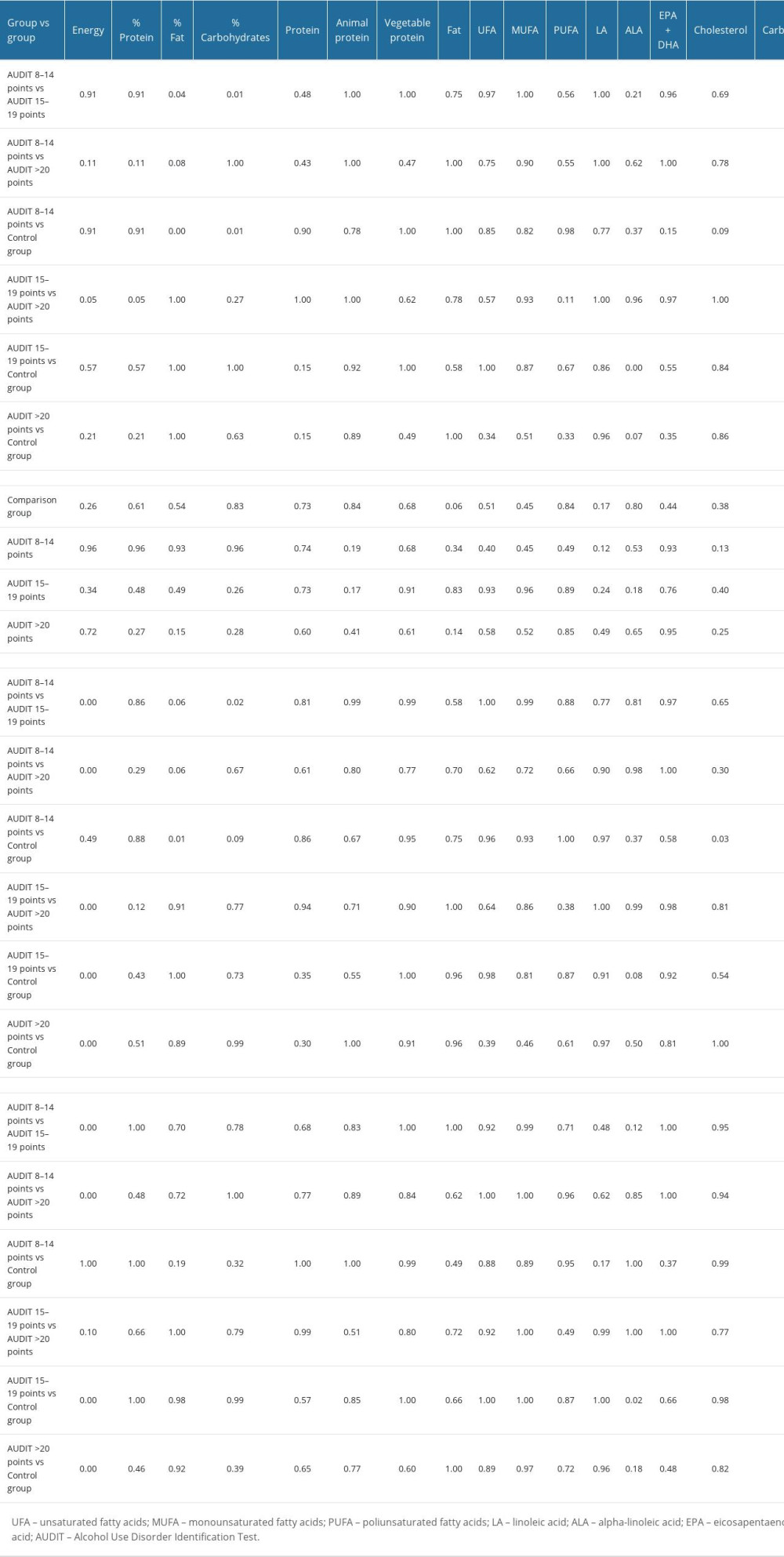

An analysis of the values obtained for the BSA scale showed that patients whose test score was higher than a significantly higher BSA value characterized 7 points compared to patients in the comparison group (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05). The percentage of BSA increased as the alcohol dependence score assessed by the AUDIT scale increased (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05). There were statistically significant differences in the percentage value of BSA between different subgroups based on the AUDIT scores (Table 5; P<0.05) between the comparison group and the group of patients who scored 15–19 on the AUDIT test (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05) and between the control and the group of patients who scored at least 20 on the AUDIT test (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05). Smoking alone did not statistically affect BSA percentage (Tables 2, 5; P>0.05). Nevertheless, a two-factor ANOVA (analysis of variance) showed that among patients who did not smoke, there was a statistically significant change in BSA among alcohol-dependent patients, as well as in the comparison of the comparison group and patients who scored less than 15 points on the AUDIT test (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05). However, among patients who smoked tobacco, statistically significant differences were noted between the group characterized by risky drinking (AUDIT score of 8–14 points) and the group represented by harmful drinking (AUDIT score of 15–19 points) (Tables 2, 5; P<0. 05). A similar outcome was observed between the group with risky drinking (AUDIT score 8–14 points) and the group with a high risk of alcohol dependence (AUDIT score >20 points) (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05), and between the comparison group and the group of patients who scored >20 points on the AUDIT test (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05).

ASSESSMENT OF THE SEVERITY OF PSORIATIC LESIONS ON PATIENTS IN THE STUDY AND COMPARISON GROUPS BASED ON THE PASI SCALE:

Based on values obtained for the PASI scale, patients whose AUDIT score indicated a risky pattern of alcohol consumption had a significantly higher BSA value than patients in the comparison group (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05). The percentage of PASI increased with an increase in the alcohol dependence score assessed by the AUDIT scale (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05), with a non-significant difference in the PASI value between the group of patients who scored between 15–19 points and above 20 points (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05).

Statistical analysis showed statistically significant differences in PASI values between different subgroups based on AUDIT score (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05), between the comparison group and the group of patients who scored 15–19 points on the AUDIT test (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05), and between the comparison group and the group of patients who scored at least 20 points on the AUDIT test (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05).

Smoking was not shown to significantly affect the PASI percentage (Tables 2, 5; P>0.05). However, a two-factor ANOVA showed that among patients who did or did not smoke tobacco, changes in percent PASI changed significantly in alcohol-dependent patients, as well as for the comparison between the comparison group and patients who scored at least 15 points on the AUDIT test (Tables 2, 5; P<0.05).

ASSESSMENT OF QUALITY OF LIFE IN PATIENTS IN THE STUDY GROUP AND COMPARISON GROUP BASED ON THE DLQI SCALE:

The statistical analysis conducted did not confirm that alcohol consumption, pattern of alcohol consumption, and smoking had a significant effect on the quality of life of patients in the study group and comparison group (Tables 2, 5; P>0.05). Nevertheless, in the comparison group, psoriasis had a moderate effect on patient QoL. In contrast, the study group exhibited a range from a very large impact on patient quality of life to an extremely large effect on patient QoL, with a greater reduction in QoL with higher AUDIT scores (Tables 2, 5; P>0.05).

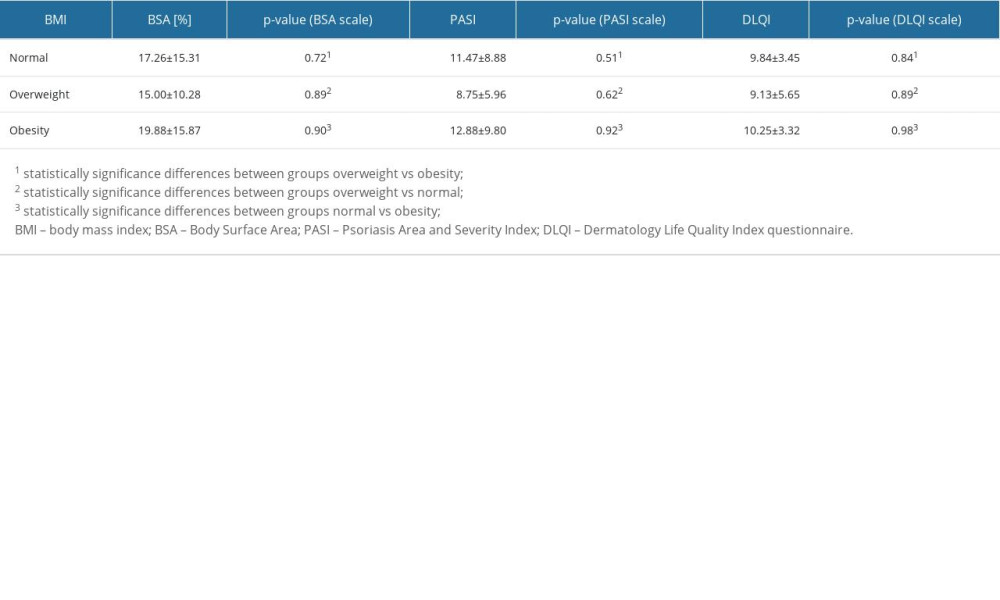

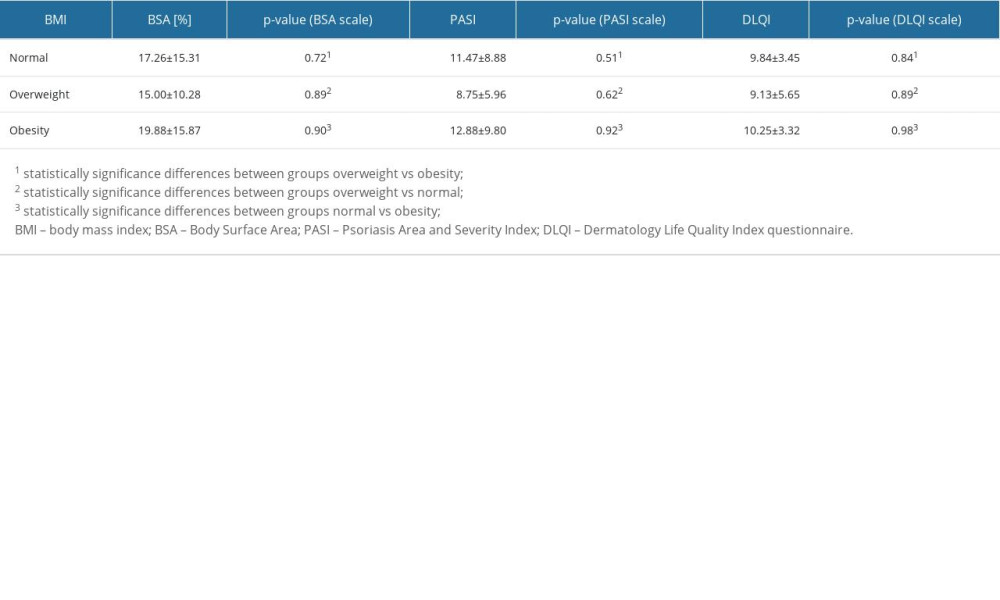

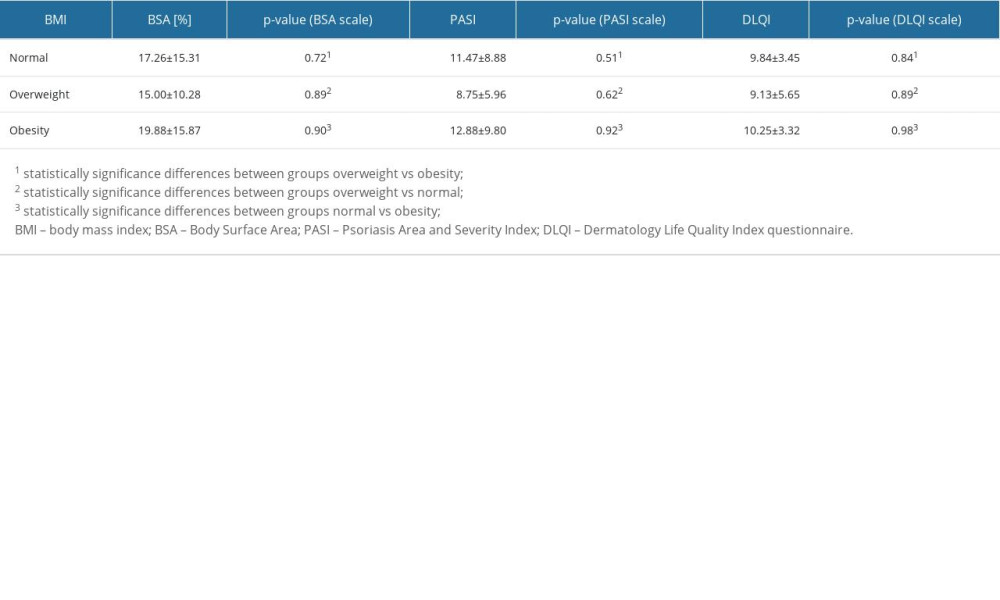

ASSESSMENT OF PSORIATIC LESION SEVERITY AND QOL IN PATIENTS IN THE STUDY GROUP AND COMPARISON GROUP IN RELATION TO BMI:

Next, we evaluated whether overweight and obesity significantly contributed to the severity of psoriatic lesions, assessed using the BSA and PASI scales, and whether they affected patients’ QoL in the study group and comparison group (Table 6; P>0.05). Statistical analysis did not show that overweight and obesity significantly affected the severity of psoriatic lesions and patients’ QoL in either group (Table 6; P>0.05). With regard to the BSA and PASI scales, the most advanced changes were noted successively in obese patients, followed by normal-weight and overweight patients (Table 6; P>0.05). The same trend was noted with regard to QoL (Table 6; P>0.05).

EVALUATION OF DIETARY ENERGY VALUE, INTAKE OF PROTEIN, FAT, DIGESTIBLE CARBOHYDRATES, FIBER, AND FATTY ACIDS OF PATIENTS WITH PSORIASIS VULGARIS:

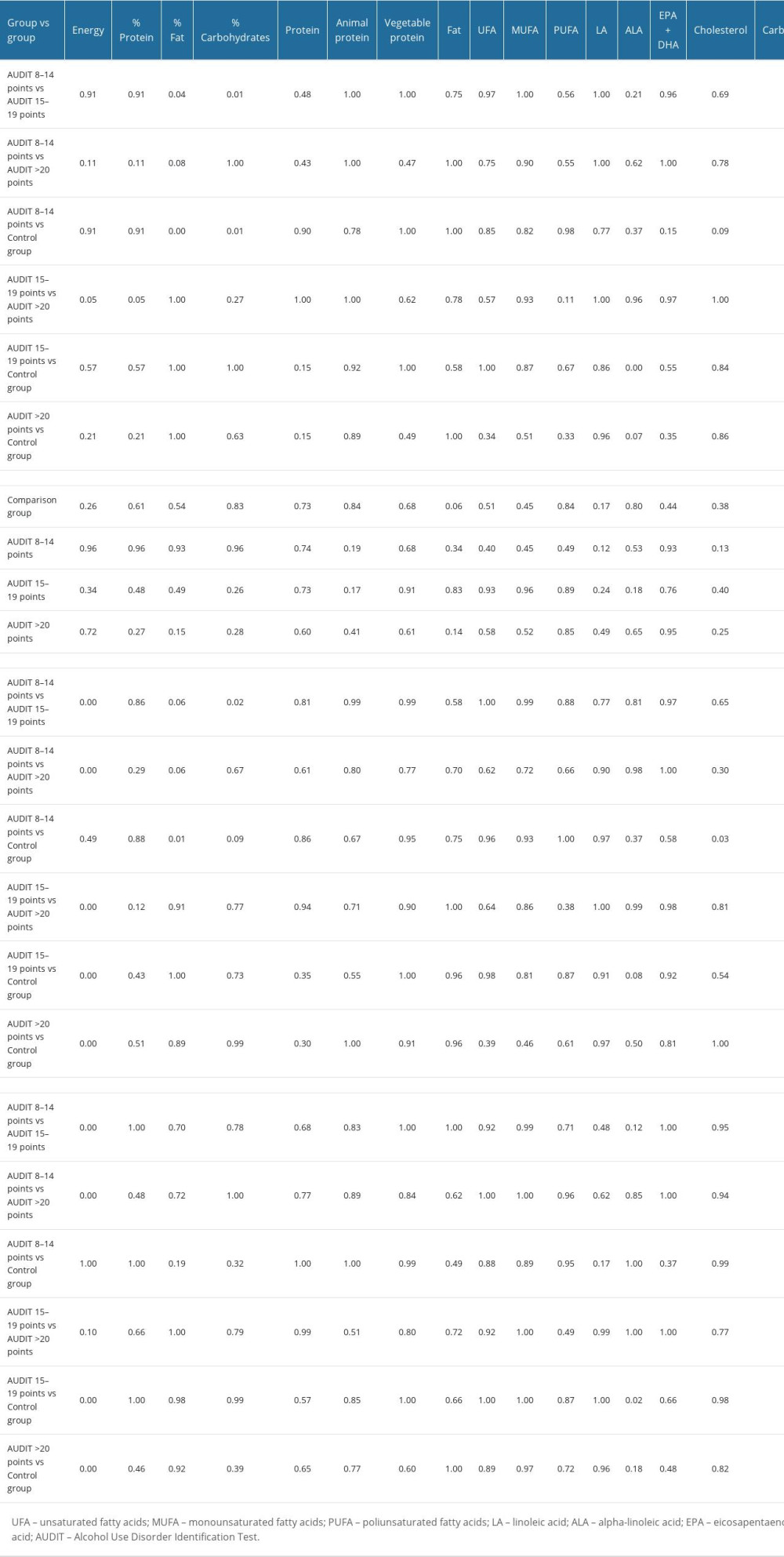

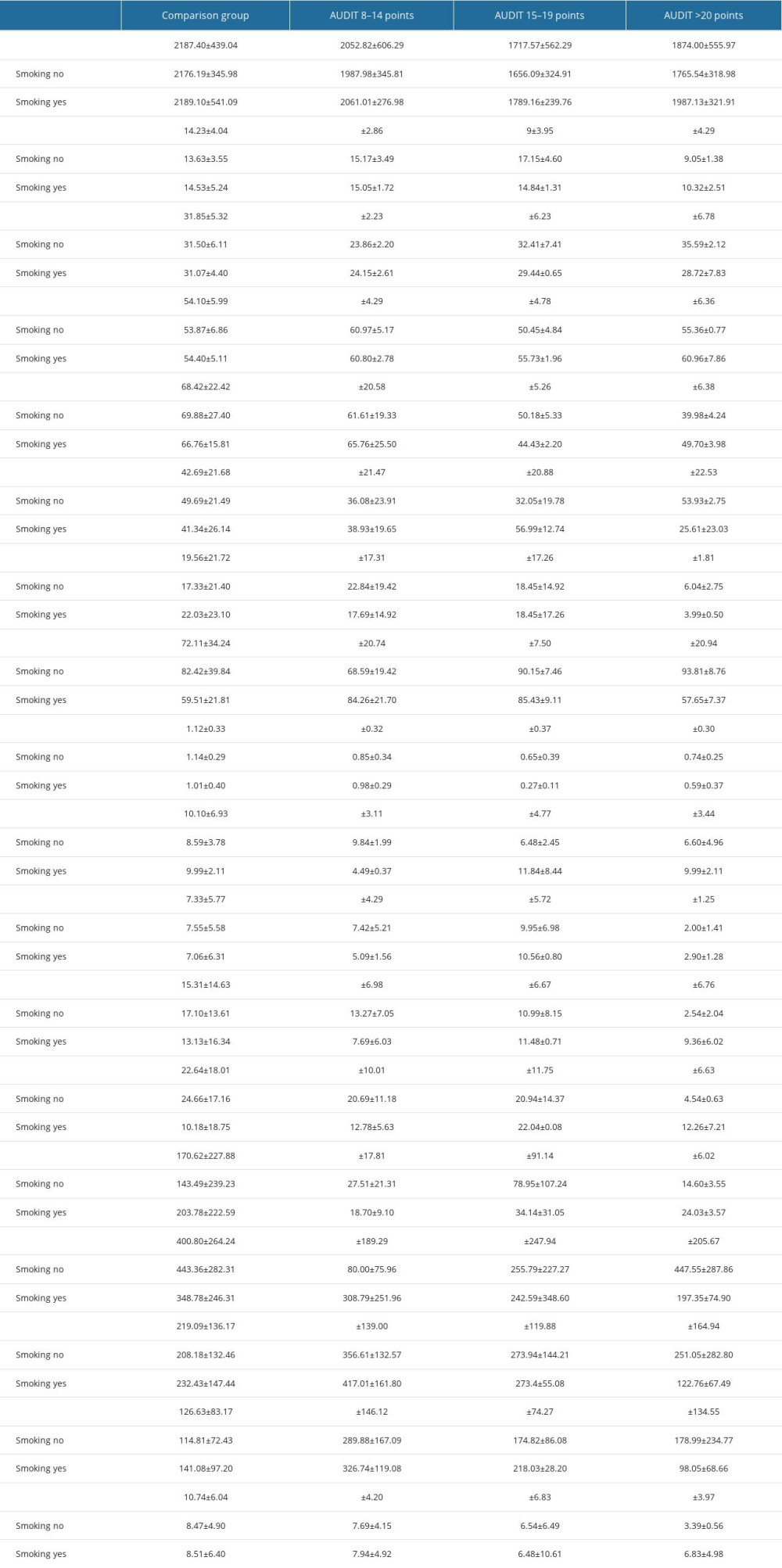

The energy value of meals in the study group and comparison group patients was inadequate, according to the group’s energy requirements, with the lowest energy value for whole-day rations recorded among patients who scored between 15–19 points on the AUDIT test. By contrast, among patients at high risk for alcohol dependence (AUDIT >20 points), the caloric value of meals was slightly higher (Tables 4, 7). Nevertheless, the statistical analysis performed, a two-factor ANOVA and a post hoc test, did not show that the energy value of meals in each group depended on the pattern of alcohol consumption or smoking (Table 8; P>0.05).

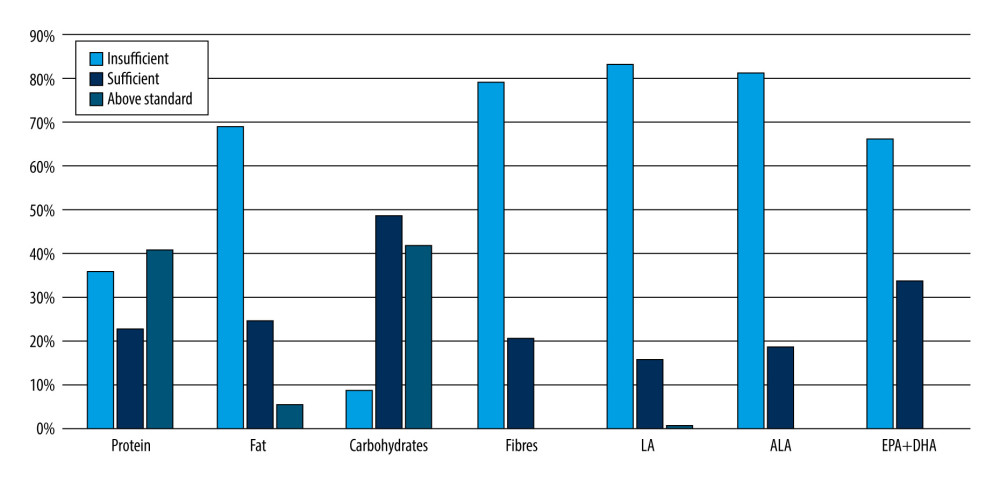

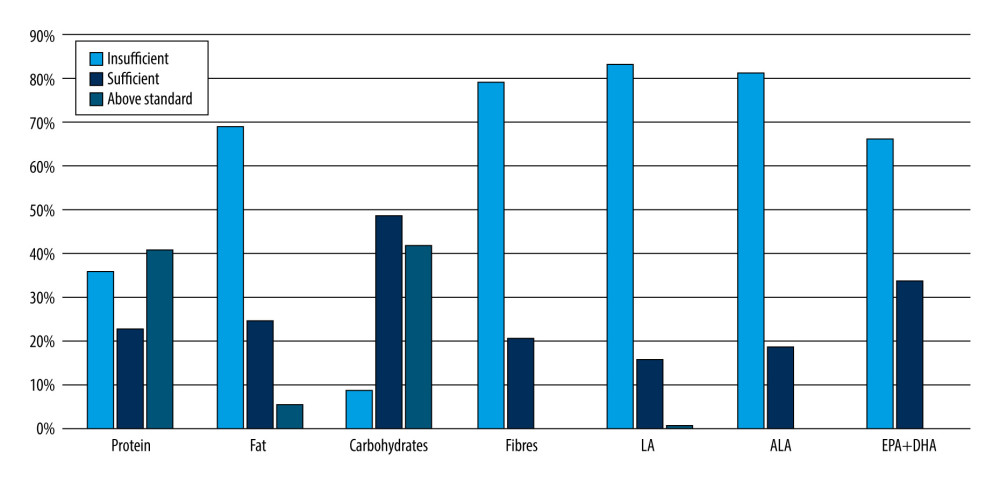

Total protein intake in the comparison group and among patients who scored 8–14 on the AUDIT test exceeded the average requirement norm. By contrast, total protein intake was below the recommended amount for patients in the study group who scored 15 or more on the AUDIT test, with the deficit worsening with the risk of alcohol dependence (Tables 2, 6). Evaluating the diet of patients with psoriasis vulgaris, we observed that only 23% had a diet that met the recommended protein intake, 36% had an inadequate supply of protein from food, and 41% had an excessive protein intake (Figure 2). Nevertheless, a two-factor ANOVA and a post hoc test did not show that total protein intake in each group depended on the pattern of alcohol consumption or smoking (Table 8; P>0.05).

Furthermore, in 69% of patients the diet did not meet the recommended intake of fats, including unsaturated fatty acids. Only 1 in 4 patients had sufficient dietary fat intake (Figure 2). The dietary intake of total fats in the study and comparison groups was lower than the recommended standard. Among patients with psoriasis vulgaris, based on the percentage of those with sufficient intake, there was a high likelihood of deficient intake of unsaturated fatty acids, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid + docosahexaenoic acid (EPA+DHA), where sufficient dietary intake was noted in only 34% of patients (Tables 4, 8). Dietary intake of linoleic acid (LA) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) was sufficient in only 16% and 19% of patients with psoriasis vulgaris, respectively. The most significant deficiencies in total fats and unsaturated fatty acids were found in patients who scored 20 or more on the AUDIT test (Tables 4, 8). Nevertheless, two-factor ANOVA and post hoc test did not show that the intake of total fats and unsaturated fatty acids in each group depended on the pattern of alcohol consumption or smoking (Table 8; P>0.05).

In addition, in the diets of patients with psoriasis vulgaris, 42% contained too much assimilable carbohydrate; assimilable carbohydrate intake was insufficient in 9%; and assimilable carbohydrate intake was normal in 49% (Tables 4, 8). Nevertheless, two-factor ANOVA and a post hoc test did not show that the intake of total carbohydrates and assimilable carbohydrates in each group depended on the pattern of alcohol consumption or smoking (Table 8; P>0.05).

Similarly, we also found that 79% of patients’ diets were low in fiber, both in the control and study groups, regardless of the AUDIT test scores, with the differences not being statistically significant (Tables 4, 6, 8; P<0.05; Figure 2).

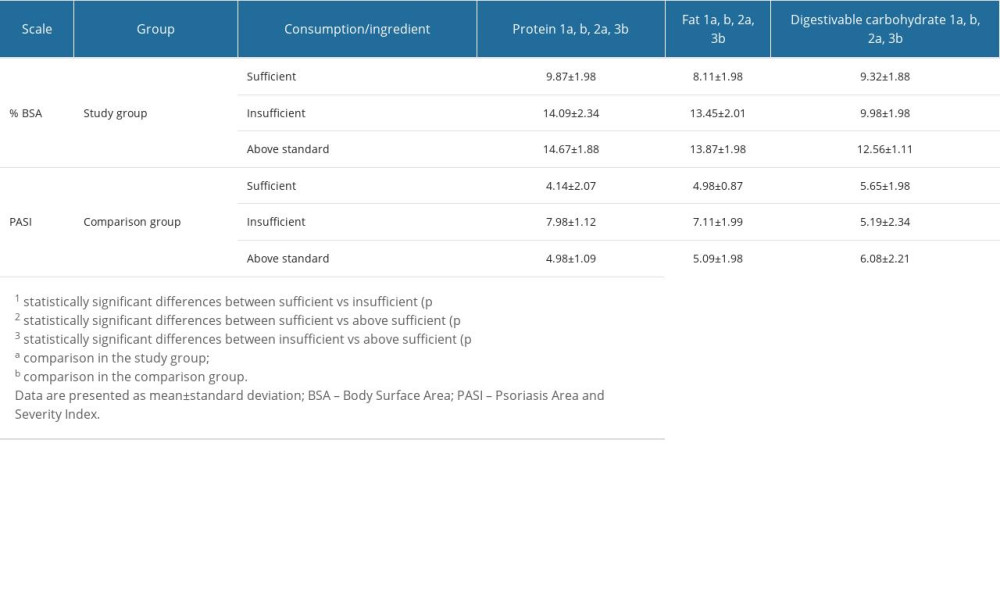

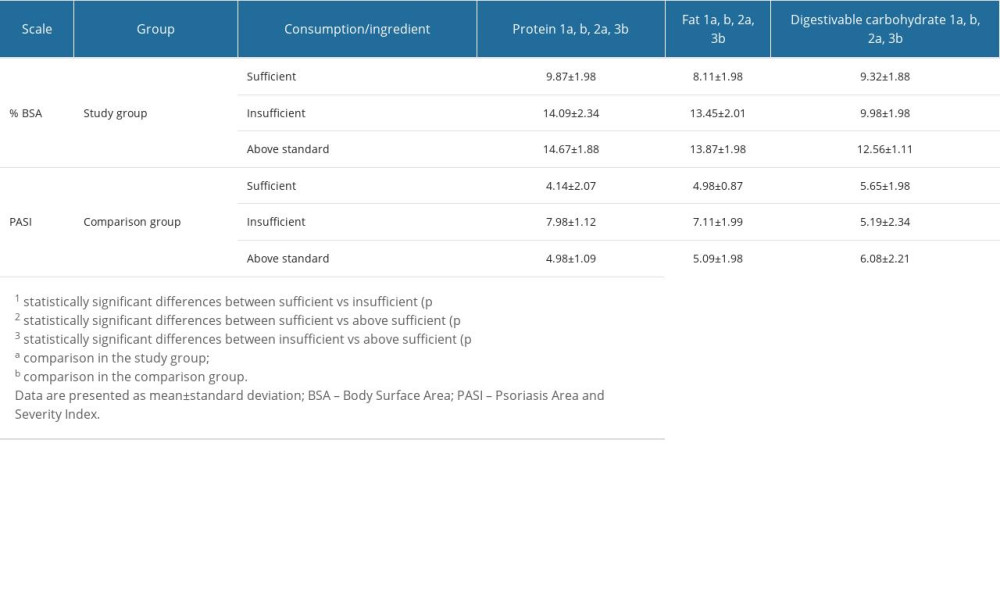

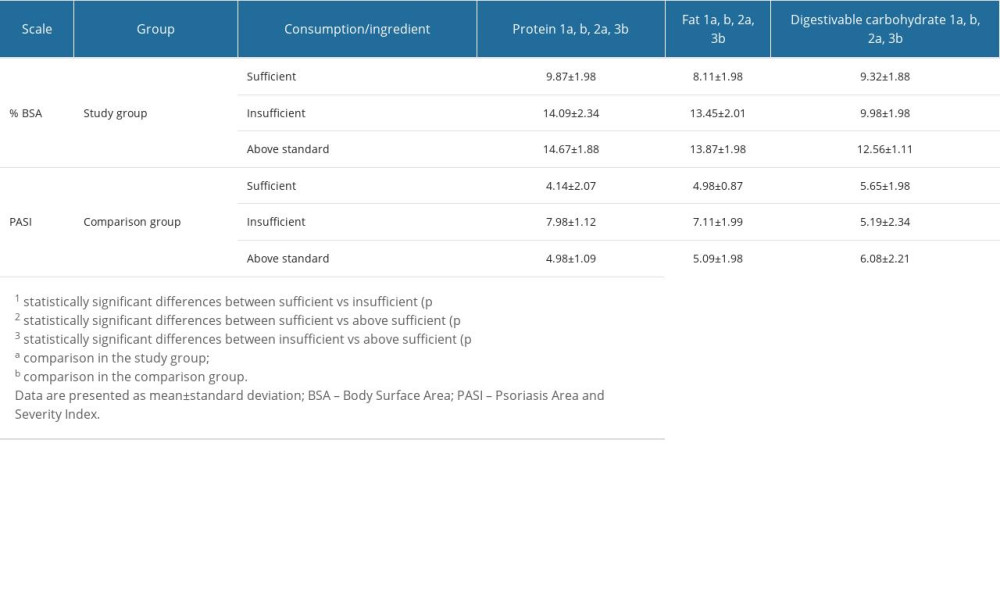

ASSESSMENT OF PSORIATIC LESION SEVERITY USING BSA AND PASI SCALES IN THE STUDY GROUP AND COMPARISON GROUP IN RELATION TO SUFFICIENT PROTEIN, FAT, AND CARBOHYDRATE INTAKE:

We assessed the severity of psoriatic lesions in patients in both groups according to whether the group’s intake of total protein, total fat, and assimilable carbohydrates was sufficient or higher/lower than recommended levels (Tables 4, 9). We noted that both inadequate and excessive dietary intake of total protein, total fat, and assimilable carbohydrates were associated with significantly higher values on BSA and PASI scales and, thus, more severe psoriasis lesions (Table 9; P<0.05). For the BSA scale, statistically significant differences were found in comparing patients with sufficient and non-sufficient nutrient intake and between those with sufficient intake and those who exceeded the norm (Table 9; P<0.05). For the PASI scale, statistically significant differences were found in the comparisons of those with sufficient and non-sufficient nutrient intake and between those with sufficient intake and those who exceeded the norm (Table 9; P<0.05).

Discussion

A survey of 72 209 respondents from 21 countries, with no less than 250 people from each country responding, analyzed reasons that motivate people to change their alcohol consumption patterns [46]. In the survey findings, Poland had the highest percentage of people (41%) who said they would reduce alcohol consumption [46]. The findings indicated that the most common motivating factors for reducing alcohol consumption included sexual assault (France), physical health improvement (Brazil, Portugal, Spain), mental health problems (Portugal), violent incidents (France), trauma incidents (Greece), trouble with the police (USA), and embarrassment (Greece) [46]. In Poland, motivation was related to financial concerns, violent incidents, and sexual assault [46].

Given the alarming trend of increasing risky alcohol consumption presented above and the fact that the number of studies on the impact of alcohol consumption on the course of psoriasis vulgaris is relatively small, the present study focused on analyzing this problem [33,47,48]. Poikolainen et al noted that men with psoriasis consumed an average of 42.9 g of alcohol per day, while healthy volunteers drank an average of 21 g of alcohol per day (

Our study assessed the severity of psoriatic lesions using 2 commonly used scales: PASI and BSA. This allowed an authoritative and independent assessment of skin lesions. This procedure is recommended because each of these indices has certain limitations. The PASI scale is a complex scale with a theoretical upper limit and the possibility of error in determining the severity of psoriatic lesions, where the relationship between the score and the severity of skin lesions is non-linear. BSA scores are overestimated in mild psoriasis, and the scale does not consider the morphology of skin lesions [51]. The obtained values of BSA and PASI in the study group about alcohol consumption suggest that consuming only higher doses of alcohol is associated with a more severe course of psoriasis compared to the comparison group.

Nonetheless, further research is required, especially on a larger patient population. A study conducted by Gerdes et al in 1203 patients hospitalized for psoriasis found an association between the severity of psoriatic lesions expressed on the PASI scale and alcohol consumption [52]. Our analysis also confirmed that the severity of psoriatic lesions, as determined by the PASI scale, increased with increasing alcohol consumption (

It seems that exacerbation of the course of psoriasis in those who consume alcohol is associated with more frequent mechanical trauma, greater susceptibility to infections, and unfavorable changes in the differentiation of particular subpopulations of T lymphocytes, which interfere with the immune response [53]. The problem of determining the potential effect of alcohol on the severity of the course of psoriasis was also analyzed in the Indian subcontinent by Mahajan et al, who found that only men (32.9%) consumed alcohol, and 19.9% of them drank occasionally (AUDIT score <8). Another 67.1% of patients abstained entirely from alcohol consumption (AUDIT score 0). The remaining 13% regularly drank (AUDIT score ≥8) and had a more severe disease course compared to abstainers (

By contrast, observations by de Vocht et al suggest that the AUDIT score depends on the month and time of day the questionnaire is completed, indicating some seasonality in the questionnaire results obtained and limitations of the AUDIT test itself [55]. Alcohol consumption, especially in a risky manner, significantly limits possible therapeutic options for psoriasis [6,12]. In the patients in the present study, topical treatment was most often used, followed by light therapy or systemic treatment. Therefore, the evaluated therapy efficacy was lower than expected, as modern drugs with anti-cytokine effects cannot be included [6,11,12,56].

Based on the results presented in this study, a decrease in quality of life was observed with an increase in AUDIT score and risk of alcohol dependence (

Wei et al. in their meta-analysis showed that the onset of psoriasis and its clinical course is influenced by how early smoking started, the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and lifetime smoking [58]. In contrast, they did not find a causal relationship between alcohol consumption and psoriasis [58].

Nevertheless, it is essential to remember that smoking is a risk factor for the development of psoriasis; it is positively associated with the disease at the population level but negatively related to patients with psoriasis, a phenomenon referred to as the “smoking paradox” in psoriasis (smoking being protective of PsA) [59,60]. Nevertheless, Dey et al [61] pointed out that the “smoking paradox” is due to a methodological error in the meta-analysis conducted by Gazel et al [62], who included observations made by Nguyen et al [63]. Admittedly, Nguyen et al indicated that smoking increases the risk of psoriatic arthritis among smokers in the general population, but when only people with psoriasis were included, a different result was obtained [42,44].

However, the combination of excessive alcohol consumption and smoking contributes to the exacerbation of psoriasis lesions. We further assessed whether the diet of the study group and comparison group patients was balanced and provided sufficient coverage of the recommended amounts of protein, carbohydrates, and fats, including unsaturated fatty acids and fiber. We found a BMI above normal in 28 of the 44 patients included in the study. In their systematic review, Mahil et al found that excessive body weight is a significant factor in the occurrence of psoriasis and the greater severity of lesions [64]. A multicenter study by Pirro et al showed that obese patients diagnosed with psoriasis vulgaris had a worse clinical response to biologic therapy [65]. In the present study, we showed that overweight or obese patients had higher scores in BSA and PASI than did normal-weight patients, although the differences were insignificant (

In both groups, patients with risky alcohol consumption patterns tended to have excessive protein intake. A dietary protein deficit was noted for patients who scored >15 points on the AUDIT test. Zacheim et al [66] and Knopp et al [67] indicated that the severity of psoriatic lesions is not dependent on dietary protein [31,42,43]. Unfortunately, there is a lack of long-term studies on protein intake versus inflammatory marker levels. For example, Gögebakan et al showed significantly lower levels of C-reactive protein in patients on a low-protein diet compared to those on a high-protein diet [68]. Lopez-Legarrea et al reported higher levels of inflammatory markers in patients on a high-protein diet, with only animal protein taken into account [69].

In the present study, the most significant deviations and abnormalities were found in fat intake in both groups of patients, and in 69% of the patients, the diet did not meet the daily fat requirements. We also found a significant deficiency in the intake of unsaturated fatty acids, especially EPA+DHA. Scientific reports confirm the beneficial effects of unsaturated fatty acids on the human body. Monounsaturated fatty acids are involved in protecting cell membranes from the harmful effects of oxidation [70]. By contrast, polyunsaturated fatty acids, which include the omega-3 and omega-6 groups of fatty acids, must be supplied with food or supplemented, as they are not synthesized by humans [71]. Wolters et al [72] and Kragballe et al [73] noted that a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids resulted in a statistically significant reduction in PASI [46,47]. Miilsop et al indicated that supplementation with EPA and DHA acids was associated with clinical improvement in psoriatic lesions. The beneficial effects of omega-3 fatty acids are related to their anti-inflammatory effects, as they participate in synthesizing compounds with anti-inflammatory effects [50]. Baran et al showed a positive relationship between the severity of psoriatic lesions and the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 fatty acids and a negative relationship for the concentration of EPA and DHA [40]. Ensuring an adequate intake of fats, including unsaturated fatty acids, in patients with psoriasis is also crucial because the pathway of unsaturated fatty acid synthesis is impaired in psoriasis [74].

Higher-than-recommended intake of assimilable carbohydrates, with concomitant under-consumption of dietary fiber, was found in a significant proportion of patients in both groups. A diet low in fiber negatively affects the intestinal microflora due to a decrease in the production of beneficial bacteria, which is a factor predisposing to inflammatory diseases [75,76]. Further, excessive intake of simple sugars is associated with exacerbation of psoriatic lesions by intensifying oxidative stress, as well as reducing the beneficial effects of omega-3 fatty acids on the body [77]. The diet of patients with psoriasis should be rich in dietary fiber, which reduces oxidative stress, and low in simple carbohydrates [70]. Thus, patient education on dietary management and eliminating stimulants are essential aspects of psoriasis therapy and achieving an adequate response to treatment. This, in turn, requires the patient to follow recommendations.

This is all the more important because alcohol abuse limits the available treatment options; therefore, the available treatment options may not be effective [6,11]. Ferrari et al emphasized that modern methods of treating dermatoses, despite being expensive, are also effective [78]. Therefore, they will probably be used more widely in the near future [78]. Therefore, to tailor treatment for patients of different ages and severity of psoriasis, further development of personalized medicine targeting the molecular targets underlying the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis is needed, as well as the search for new molecular markers to effectively monitor the loss of adequate response to treatment before the onset of phenotypic symptoms [6,11,78].

Our study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. Among the most significant factors is that it was a study of a relatively small number of participants recruited from a single center. Further, we only included patients with diagnosed psoriasis vulgaris of moderate severity, with a long history of the disease, previously treated with topical and then conventional systemic therapy. Thus, patients with newly diagnosed psoriasis who had not been previously treated for psoriasis were not included, which probably affected the BSA, PASI, and DLQI values. Therefore, it is reasonable to study a larger number of participants to verify the hypothesis of the influence of BMI on the severity of psoriatic lesions. Nevertheless, considering that alcohol abuse is an embarrassing problem, study participants may intentionally or subconsciously answer the AUDIT questionnaire to obtain a lower score than the actual score. It is also likely that the patients recruited for the study did not declare their actual alcohol consumption [79] and adopted a “drinking self-image” when answering rather than specific memories of actual drinking events [80].

Conclusions

We found that the severity of psoriatic lesions in patients with psoriasis vulgaris depends significantly on the pattern of alcohol consumption. As the amount and frequency of alcohol consumption increase, the severity of psoriasis vulgaris skin lesions considerably worsens. In addition, the diet of patients with psoriasis vulgaris is often abnormal and needs to be modified, especially with regard to the supplementation of EPA, DHA, and dietary fiber deficiencies. It is necessary to develop comprehensive care for patients with psoriasis and comorbid alcohol problems.

Figures

Figure 1. Number of patients in the study and comparison group who were underweight, average weight, overweight, or obese.

Figure 1. Number of patients in the study and comparison group who were underweight, average weight, overweight, or obese.  Figure 2. Percentage of patients with psoriasis vulgaris with insufficient, sufficient, or above the recommended standard intake of protein, fat, digestible carbohydrates, fiber, and fatty acids (LA, ALA, EPA+DHA). LA – linoleic acid; ALA – alpha-linoleic acid; EPA – eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA – docosahexaenoic acid.

Figure 2. Percentage of patients with psoriasis vulgaris with insufficient, sufficient, or above the recommended standard intake of protein, fat, digestible carbohydrates, fiber, and fatty acids (LA, ALA, EPA+DHA). LA – linoleic acid; ALA – alpha-linoleic acid; EPA – eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA – docosahexaenoic acid. Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the study group, including social and anthropometric parameters. Table 2. Parameters of clinical severity of psoriasis vulgaris and quality of life of patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to alcohol and smoking patterns.

Table 2. Parameters of clinical severity of psoriasis vulgaris and quality of life of patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to alcohol and smoking patterns. Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study and comparison groups.

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study and comparison groups. Table 4. Estimated energy requirements estimated average conditions, and adequate intake standards for energy and nutrients in men and women.

Table 4. Estimated energy requirements estimated average conditions, and adequate intake standards for energy and nutrients in men and women. Table 5. Results of the post hoc test of two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance for the parameters%BSA, PASI, and DLQI.

Table 5. Results of the post hoc test of two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance for the parameters%BSA, PASI, and DLQI. Table 6. Assessment of psoriatic lesion severity and quality of life in patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to BMI.

Table 6. Assessment of psoriatic lesion severity and quality of life in patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to BMI. Table 7. Results of post hoc two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance test for energy and nutrients in patients with psoriasis vulgaris assigned to the study and comparison groups.

Table 7. Results of post hoc two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance test for energy and nutrients in patients with psoriasis vulgaris assigned to the study and comparison groups. Table 8. Evaluation of energy value and basic nutrients in the diets of patients in the study and comparison groups.

Table 8. Evaluation of energy value and basic nutrients in the diets of patients in the study and comparison groups. Table 9. The severity of psoriatic lesions using the BSA and PASI scales in the study and comparison group in relation to sufficient intake of protein, fat, and carbohydrates and results of post hoc one-way ANOVA analysis of variance test for the parameters BSA and PASI.

Table 9. The severity of psoriatic lesions using the BSA and PASI scales in the study and comparison group in relation to sufficient intake of protein, fat, and carbohydrates and results of post hoc one-way ANOVA analysis of variance test for the parameters BSA and PASI.

References

1. Branisteanu DE, Cojocaru C, Diaconu R, Update on the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis: Exp Ther Med, 2022; 23(3); 1-13

2. Georgescu SR, Tampa M, Caruntu C, Advances in understanding the immunological pathways in psoriasis: Int J Mol Sci, 2019; 20(3); 739

3. Kowalewska B, Cybulski M, Jankowiak B, Krajewska-Kułak E, Acceptance of illness, satisfaction with life, sense of stigmatization, and quality of life among people with psoriasis: A cross-sectional study: Dermatol Ther, 2020; 10; 413-30

4. Badri T, Kumar P, Oakley AM, Plaque psoriasis: StatPearls August 8, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

5. Purzycka-Bohdan D, Kisielnicka A, Zabłotna M, Chronic plaque psoriasis in Poland: Disease severity, prevalence of comorbidities, and quality of life: J Clin Med, 2022; 11(5); 1254

6. Reich A, Adamski Z, Chodorowska G, Psoriasis. Diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations of the Polish Dermatological Society. Part 1: Dermatol Rev Dermatol, 2020; 107(2); 92-108

7. van Acht MR, van den Reek JM, de Jong EM, Seyger MM, The effect of lifestyle changes on disease severity and quality of life in patients with plaque psoriasis: A narrative review: Psoriasis (Auckl), 2022; 12; 35-51

8. Grabarek B, Schweizer P, Adwent I, Differences in expression of genes related to drug resistance and miRNAs regulating their expression in skin fibroblasts exposed to adalimumab and cyclosporine A: Adv Dermatol Allergol Dermatol Alergol, 2020; 38(2); 249-55

9. Wielowieyska-Szybińska D, Wojas-Pelc A, Psoriasis: Course of disease and treatment: Adv Dermatol Allergol Dermatol Alergol, 2012; 29(2); 118-22

10. Pogorzelska-Antkowiak A, Diagnostyka łuszczycy za pomocą dermoskopu i mikroskopu konfokalnego: Forum Dermatologicum, 2019; 5; 11-13 [in Polish]

11. Reich A, Adamski Z, Chodorowska G, Psoriasis. Diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations of the Polish Dermatological Society. Part 2: Dermatol Rev Dermatol, 2020; 107(2); 110-37

12. Strzałka-Mrozik B, Krzaczyński J, Farmakologiczne i niefarmakologiczne metody terapii łuszczycy ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem leków biologicznych: Farm Pol, 2020; 76(6); 333-43 [in Polish]

13. Golbari NM, van der Walt JM, Blauvelt A, Psoriasis severity: Commonly used clinical thresholds may not adequately convey patient impact: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2021; 35(2); 417-21

14. Bożek A, Reich A, W jaki sposób miarodajnie oceniać nasilenie łuszczycy?: Forum Dermatologicum, 2016; 2; 6-11 [in Polish]

15. Hägg D, Sundström A, Eriksson M, Schmitt-Egenolf M, Severity of psoriasis differs between men and women: A study of the clinical outcome measure psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) in 5438 Swedish register patients: Am J Clin Dermatol, 2017; 18; 583-90

16. Bożek A, Reich A, The reliability of three psoriasis assessment tools: Psoriasis area and severity index, body surface area and physician global assessment: Adv Clin Exp Med, 2017; 26(5); 851-56

17. Gerdes S, Körber A, Biermann M, Karnthaler C, Reinhardt M, Absolute and relative psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) treatment goals and their association with health-related quality of life: J Dermatol Treat, 2020; 31(5); 470-75

18. Walsh JA, Jones H, Mallbris L, The Physician Global Assessment and Body Surface Area composite tool is a simple alternative to the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index for assessment of psoriasis: Post hoc analysis from PRISTINE and PRESTA: Psoriasis (Auckl), 2018; 8; 65-74

19. Smith LS, Take a deeper look into body surface area: Nursing2022, 2019; 49(9); 51-54

20. Zafar MA, Li Y, Rizzo JA, Height alone, rather than body surface area, suffices for risk estimation in ascending aortic aneurysm: J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2018; 155(5); 1938-50

21. Tiling-Grosse S, Rees J, Assessment of area of involvement in skin disease: A study using schematic figure outlines: Br J Dermatol, 1993; 128(1); 69-74

22. Lewis V, Finlay AY, 10 years experience of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc, 2004; 9(2); 169-80

23. Finlay AY, Khan G, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use: Clin Exp Dermatol, 1994; 19(3); 210-16

24. Badia , Mascaró , Lozano CR Group, Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with mild to moderate eczema and psoriasis: clinical validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of the DLQI: Br J Dermatol, 1999; 141(4); 698-702

25. Kamiya K, Kishimoto M, Sugai J, Risk factors for the development of psoriasis: Int J Mol Sci, 2019; 20(18); 4347

26. Rapalli VK, Waghule T, Gorantla S, Psoriasis: pathological mechanisms, current pharmacological therapies, and emerging drug delivery systems: Drug Discov Today, 2020; 25(12); 2212-26

27. Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J, Diagnosis and management of psoriasis: Can Fam Physician, 2017; 63(4); 278-85

28. Ożóg MK, Grabarek BO, Wierzbik-Strońska M, Świder M, Neurological complications of biological treatment of psoriasis: Life, 2022; 12(1); 118

29. Dopytalska K, Ciechanowicz P, Wiszniewski K, The role of epigenetic factors in psoriasis: Int J Mol Sci, 2021; 22(17); 9294

30. Svanström C, Lonne-Rahm SB, Nordlind K, Psoriasis and alcohol: Psoriasis (Auckl), 2019; 9; 75-79

31. Szentkereszty-Kovács Z, Gáspár K, Szegedi A, Alcohol in psoriasis – from bench to bedside: Int J Mol Sci, 2021; 22(9); 4987

32. Qureshi AA, Dominguez PL, Choi HK, Alcohol intake and risk of incident psoriasis in US women: A prospective study: Arch Dermatol, 2010; 146(12); 1364-69

33. Brenaut E, Horreau C, Pouplard C, Alcohol consumption and psoriasis: A systematic literature review: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2013; 27; 30-35

34. Wolk K, Mallbris L, Larsson P, Excessive body weight and smoking associates with a high risk of onset of plaque psoriasis: Acta Derm Venereol, 2009; 89(5); 492-97

35. Reinert DF, Allen JP, The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): A review of recent research: Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2002; 26(2); 272-79

36. Higgins-Biddle JC, Babor TF, A review of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT for screening in the United States: Past issues and future directions: Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 2018; 44(6); 578-86

37. Nadkarni A, Garber A, Costa S, Auditing the AUDIT: A systematic review of cut-off scores for the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in low-and middle-income countries: Drug Alcohol Depend, 2019; 202; 123-33

38. Controne I, Scoditti E, Buja A, Do sleep disorders and western diet influence psoriasis? A scoping review: Nutrients, 2022; 14(20); 4324

39. Nayak RR, Western diet and psoriatic-like skin and joint diseases: A potential role for the gut microbiota: J Invest Dermatol, 2021; 141(7); 1630-32

40. Honda T, Kabashima K, Current understanding of the role of dietary lipids in the pathophysiology of psoriasis: J Dermatol Sci, 2019; 94(3); 314-20

41. Solis MY, deMelo NS, Macedo MEM, Nutritional status and food intake of patients with systemic psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis associated: Einstein (Sao Paulo), 2012; 10; 44-52

42. Garbicz J, Całyniuk B, Górski M, Nutritional therapy in persons suffering from psoriasis: Nutrients, 2022; 14(1); 119

43. Gronowska-Senger A, Przewodnik metodyczny badań sposobu żywienia: Polska Akademia Nauk, 2013 [in Polish]

44. Kuchanowicz H, Przygoda B, Nadolna I, Iwanow K, Tabele składu i wartości odżywczej żywności: PZWL Wydawnictwo Lekarskie, 2020 [in Polish]

45. : Sample Size Calculator https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html?type=1&cl=95&ci=4.14&pp=2&ps=120000&x=93&y=26

46. Davies EL, Conroy D, Winstock AR, Ferris J, Motivations for reducing alcohol consumption: An international survey exploring experiences that may lead to a change in drinking habits: Addict Behav, 2017; 75; 40-46

47. Kiejna A, Piotrowski P, Adamowski TThe prevalence of common mental disorders in the population of adult Poles by sex and age structure – an EZOP Poland study: Psychiatr Pol, 2015; 49(1); 15-27 [in Polish]

48. Kowalewska B, Jankowiak B, Cybulski M, Effect of disease severity on the quality of life and sense of stigmatization in psoriatics: Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol, 2021; 14; 107-21

49. Poikolainen K, Reunala T, Karvonen J, Alcohol intake: A risk factor for psoriasis in young and middle aged men?: BMJ, 1990; 300(6727); 780-83

50. Poikolainen K, Reunala T, Karvonen J, Smoking, alcohol and life events related to psoriasis among women: Br J Dermatol, 1994; 130(4); 473-77

51. Kowalewska B, Jankowiak B, Cybulski M, Effect of disease severity on the quality of life and sense of stigmatization in psoriatics: Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol, 2021; 14; 107-21

52. Gerdes S, Zahl VA, Weichenthal M, Mrowietz U, Smoking and alcohol intake in severely affected patients with psoriasis in Germany: Dermatology, 2010; 220(1); 38-43

53. Adışen E, Uzun S, Erduran F, Gürer MA, Prevalence of smoking, alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: An Bras Dermatol, 2018; 93; 205-11

54. Mahajan VK, Dhattarwal N, Chauhan PS, The association of alcohol use disorder and chronic plaque psoriasis: Results of a pilot study: Indian Dermatol Online J, 2021; 12(1); 128

55. de Vocht F, Brown J, Beard E, Temporal patterns of alcohol consumption and attempts to reduce alcohol intake in England: BMC Public Health, 2016; 16(1); 917

56. Grabarek B, Wcislo-Dziadecka D, Gola J, Changes in the expression profile of JAK/STAT signaling pathway genes and mirnas regulating their expression under the adalimumab therapy: Curr Pharm Biotechnol, 2018; 19(7); 556-65

57. Obuchowska K, Obuchowska A, Standyło A, The relationship between the occurrence of psoriasis and depression: J Educ Health Sport, 2020; 10(9); 403-6

58. Wei J, Zhu J, Xu H, Alcohol consumption and smoking in relation to psoriasis: A Mendelian randomization study: Br J Dermatol, 2022; 187(5); 684-91

59. Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Leffondré K, Relationship between smoking and the clinical severity of psoriasis: Arch Dermatol, 2005; 141(12); 1580-84

60. Pezzolo E, Naldi L, The relationship between smoking, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2019; 15(1); 41-48

61. Dey M, Hughes DM, Zhao SS, Comment on: The impact of smoking on prevalence of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Rheumatology, 2021; 60(1); e26

62. Gazel U, Ayan G, Solmaz D, The impact of smoking on prevalence of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Rheumatology (Oxford), 2020; 59(10); 2695-710

63. Nguyen USD, Zhang Y, Lu N, Smoking paradox in the development of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis: A population-based study: Ann Rheum Dis, 2018; 77(1); 119-23

64. Mahil SK, McSweeney SM, Kloczko E, Does weight loss reduce the severity and incidence of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis? A Critically Appraised Topic: Br J Dermatol, 2019; 181(5); 946-53

65. Pirro F, Caldarola G, Chiricozzi A, Impact of body mass index on the efficacy of biological therapies in patients with psoriasis: A real-world study: Clin Drug Investig, 2021; 41(10); 917-25

66. Zackheim HS, Farber EM, Low-protein diet and psoriasis. A hospital study: Arch Dermatol, 1969; 99(5); 580-86

67. Knopp T, Bieler T, Jung R, Effects of dietary protein intake on cutaneous and systemic inflammation in mice with acute experimental psoriasis: Nutrients, 2021; 13(6); 1897

68. Gögebakan O, Kohl A, Osterhoff MA, Effects of weight loss and long-term weight maintenance with diets varying in protein and glycemic index on cardiovascular risk factors: The diet, obesity, and genes (DiOGenes) study: A randomized, controlled trial: Circulation, 2011; 124(25); 2829-38

69. Lopez-Legarrea P, de la Iglesia R, Abete I, The protein type within a hypocaloric diet affects obesity-related inflammation: The RESMENA project: Nutrition, 2014; 30(4); 424-29

70. Barrea L, Nappi F, Di Somma C, Environmental risk factors in psoriasis: The point of view of the nutritionist: Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2016; 13(7); 743

71. Sicińska P, Pytel E, Kurowska J, Koter-Michalak MSupplementation with omega fatty acids in various diseases: Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online), 2015; 69; 838-52 [in Polish]

72. Wolters M, Diet and psoriasis: Experimental data and clinical evidence: Br J Dermatol, 2005; 153(4); 706-14

73. Kragballe K, Dietary supplementation with a combination of n−3 and n−6 fatty acids (super gamma-oil marine) improves psoriasis: Acta Derm Venereol, 1989; 69(3); 265-68

74. Fusano M, Veganism in acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis: Benefits of a plant-based diet: Clin Dermatol, 2022 [Online ahead of print]

75. Ramos S, Martín MÁ, Impact of diet on gut microbiota: Curr Opin Food Sci, 2021; 37; 83-90

76. Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H, Nutrition and psoriasis: Int J Mol Sci, 2020; 21(15); 5405

77. Chilton FH, Dutta R, Reynolds LM, Precision nutrition and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: A case for personalized supplementation approaches for the prevention and management of human diseases: Nutrients, 2017; 9(11); 1165

78. Ferrari M, Donadu MG, Biondi G, Dupilumab: Direct cost and clinical evaluation in patients with atopic dermatitis: Dermatol Res Pract, 2023; 2023; e4592087

79. Kanny D, Naimi TS, Liu Y, Annual total binge drinks consumed by U.S. adults, 2015: Am J Prev Med, 2018; 54(4); 486-96

80. Greenfield TK, Kerr WC, Alcohol measurement methodology in epidemiology: Recent advances and opportunities: Addiction, 2008; 103; 1082-99

Figures

Figure 1. Number of patients in the study and comparison group who were underweight, average weight, overweight, or obese.

Figure 1. Number of patients in the study and comparison group who were underweight, average weight, overweight, or obese. Figure 2. Percentage of patients with psoriasis vulgaris with insufficient, sufficient, or above the recommended standard intake of protein, fat, digestible carbohydrates, fiber, and fatty acids (LA, ALA, EPA+DHA). LA – linoleic acid; ALA – alpha-linoleic acid; EPA – eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA – docosahexaenoic acid.

Figure 2. Percentage of patients with psoriasis vulgaris with insufficient, sufficient, or above the recommended standard intake of protein, fat, digestible carbohydrates, fiber, and fatty acids (LA, ALA, EPA+DHA). LA – linoleic acid; ALA – alpha-linoleic acid; EPA – eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA – docosahexaenoic acid. Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of the study group, including social and anthropometric parameters.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study group, including social and anthropometric parameters. Table 2. Parameters of clinical severity of psoriasis vulgaris and quality of life of patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to alcohol and smoking patterns.

Table 2. Parameters of clinical severity of psoriasis vulgaris and quality of life of patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to alcohol and smoking patterns. Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study and comparison groups.

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study and comparison groups. Table 4. Estimated energy requirements estimated average conditions, and adequate intake standards for energy and nutrients in men and women.

Table 4. Estimated energy requirements estimated average conditions, and adequate intake standards for energy and nutrients in men and women. Table 5. Results of the post hoc test of two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance for the parameters%BSA, PASI, and DLQI.

Table 5. Results of the post hoc test of two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance for the parameters%BSA, PASI, and DLQI. Table 6. Assessment of psoriatic lesion severity and quality of life in patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to BMI.

Table 6. Assessment of psoriatic lesion severity and quality of life in patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to BMI. Table 7. Results of post hoc two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance test for energy and nutrients in patients with psoriasis vulgaris assigned to the study and comparison groups.

Table 7. Results of post hoc two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance test for energy and nutrients in patients with psoriasis vulgaris assigned to the study and comparison groups. Table 8. Evaluation of energy value and basic nutrients in the diets of patients in the study and comparison groups.

Table 8. Evaluation of energy value and basic nutrients in the diets of patients in the study and comparison groups. Table 9. The severity of psoriatic lesions using the BSA and PASI scales in the study and comparison group in relation to sufficient intake of protein, fat, and carbohydrates and results of post hoc one-way ANOVA analysis of variance test for the parameters BSA and PASI.

Table 9. The severity of psoriatic lesions using the BSA and PASI scales in the study and comparison group in relation to sufficient intake of protein, fat, and carbohydrates and results of post hoc one-way ANOVA analysis of variance test for the parameters BSA and PASI. Table 1. Characteristics of the study group, including social and anthropometric parameters.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study group, including social and anthropometric parameters. Table 2. Parameters of clinical severity of psoriasis vulgaris and quality of life of patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to alcohol and smoking patterns.

Table 2. Parameters of clinical severity of psoriasis vulgaris and quality of life of patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to alcohol and smoking patterns. Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study and comparison groups.

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study and comparison groups. Table 4. Estimated energy requirements estimated average conditions, and adequate intake standards for energy and nutrients in men and women.

Table 4. Estimated energy requirements estimated average conditions, and adequate intake standards for energy and nutrients in men and women. Table 5. Results of the post hoc test of two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance for the parameters%BSA, PASI, and DLQI.

Table 5. Results of the post hoc test of two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance for the parameters%BSA, PASI, and DLQI. Table 6. Assessment of psoriatic lesion severity and quality of life in patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to BMI.

Table 6. Assessment of psoriatic lesion severity and quality of life in patients in the study and comparison groups in relation to BMI. Table 7. Results of post hoc two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance test for energy and nutrients in patients with psoriasis vulgaris assigned to the study and comparison groups.

Table 7. Results of post hoc two-factor ANOVA analysis of variance test for energy and nutrients in patients with psoriasis vulgaris assigned to the study and comparison groups. Table 8. Evaluation of energy value and basic nutrients in the diets of patients in the study and comparison groups.

Table 8. Evaluation of energy value and basic nutrients in the diets of patients in the study and comparison groups. Table 9. The severity of psoriatic lesions using the BSA and PASI scales in the study and comparison group in relation to sufficient intake of protein, fat, and carbohydrates and results of post hoc one-way ANOVA analysis of variance test for the parameters BSA and PASI.

Table 9. The severity of psoriatic lesions using the BSA and PASI scales in the study and comparison group in relation to sufficient intake of protein, fat, and carbohydrates and results of post hoc one-way ANOVA analysis of variance test for the parameters BSA and PASI. In Press

12 Mar 2024 : Database Analysis

Risk Factors of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Population-Based Study: Results from SHIP-TREND-1 (St...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943140

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Preoperative Blood Transfusion Requirements for Hemorrhoidal Severe Anemia: A Retrospective Study of 128 Pa...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943126

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) and 3 (TIMP-3) as New Markers of Acute Kidney Injury Afte...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943500

12 Mar 2024 : Review article

Optimizing Behçet Uveitis Management: A Review of Personalized Immunosuppressive StrategiesMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943240

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952